Abstract

Background: Previous studies observed an association between intimate partner violence (IPV) and increased health problems. Early detection of IPV by general practitioners (GPs) is required to prevent further harm and provide appropriate support. In general practice, a limited number of studies are available on healthcare utilization of abused women.

Objectives: The aim of the study was to investigate the healthcare utilization of abused women compared to non-abused.

Methods: The study was designed as a matched case-control study in 16 general practices in deprived areas in Rotterdam (The Netherlands). Electronic medical files of 50 victims of IPV were analysed for consultation frequency, referrals, medical prescription and reasons for encounter over a period of five years. Controls (n = 50) were non-abused women matched for general practice, age, number of children, and country of origin and education level.

Results: Abused women visited their GP almost twice as often than non-abused, in particular for social problems (OR = 3.5; 95%CI: 1.2–10.5; P = 0.01), substance abuse (OR = 4.6; 95%CI: 0.9–22.7; P = 0.05) and reproductive health problems (OR = 3.0; 95%CI: 1.3–6.8; P = 0.009). Victims of IPV were significantly more often referred for additional diagnostics (OR = 3.6; 95%CI: 1.1–12.2; P = 0.03), to mental healthcare (OR = 2.9; 95%CI: 1.2–7.1; P = 0.02) than non-victims. Abused women received 4.1 times more often a prescription for anti-depressants (95%CI: 1.5–11.6; P = 0.005) than non-abused women.

Conclusion: As compared to non-abused women, female victims of IPV visited their GP more frequently and exhibited a typical pattern of healthcare utilization. This could alert GPs to inquire about partner abuse in the past.

KEY MESSAGE(S):

The pattern of healthcare utilisation of abused women is typical: presentation of social problems, substance abuse and reproductive health issues; use of antidepressants; referral to mental healthcare and for additional diagnostics.

This typical pattern of healthcare utilization could alert general practitioners to inquire about partner abuse in the past.

Introduction

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) is regarded as an important healthcare problem, which can result in considerable distress for the victim IPV is associated with an increased healthcare utilization, burden of disease and costs (Citation1,Citation2). IPV is defined as violence caused by a partner in an intimate relationship and includes physical, mental and/or sexual abuse. Earlier studies found that at least one in three women attending general practice reported having experienced IPV (Citation2–5). A recent study in general practices in the Netherlands confirmed that 30% of the women consulting a GP did experience violence in an intimate relationship (Citation6). Patient surveys revealed a relationship between IPV and health-related problems (Citation7–11). Female victims of IPV are known to be reluctant to talk about the abuse to their general practitioner (GP), even when their health problems, such as injuries and sleeping problems, are directly caused by IPV (Citation12,Citation13). A systematic review of quantitative studies on identification of IPV reveals a baseline recognition of 0–3% by healthcare providers (Citation14). Finally, only one in ten female victims of IPV is known as such by their GP (Citation4), as identification of IPV is complicated by several factors (Citation14,Citation15).

Due to low identification of IPV, there is a lack of knowledge on healthcare needs of abused women in primary care. In many countries in western societies, the GP functions as a gatekeeper to specialist care. In this respect, it is important to identify characteristics of abused women's healthcare utilization in general practice. Given the high prevalence of partner violence and contribution to healthcare utilization and total burden of disease, improved identification of IPV is expected to provide a more appropriate response to and treatment of these patients (Citation2).

It is also acknowledged that psychotropic medication use is higher amongst abused women (Citation9,Citation16), as are high rates of chronic pain, reported in earlier studies (Citation17–20). Indeed, victims of IPV visit their GP more often with chronic (undefined) pain complaints, compared to non-abused women (Citation20–25). However, most studies did not compare results appropriately to non-abused controls. It is, therefore, currently unknown, whether these healthcare issues are solely due to IPV, or whether confounding factors, such as education, social background and/or ethnicity can explain these observations. Given the high prevalence of partner violence, negative health effects for victims and their contribution to total healthcare utilization (Citation20), it is important that GPs identify victims of IPV more often and provide appropriate responses and support. However, there is still not sufficient knowledge and understanding of use of healthcare by female victims of IPV.

The aim of this study was investigating characteristics of healthcare utilization of abused women in primary care and comparing this to non-abused women. Results of this study might support GPs recognizing victims of IPV earlier.

Methods

Study design and setting

As part of an intervention study on effects of mentor-mother support for abused women in Rotterdam (The Netherlands), we investigated the prevalence of IPV among women (> 18 years) attending 16 participating general practices in March 2009 (waiting room survey) (Citation6). The GPs had previously volunteered to follow an educational programme on recognition of IPV. To study the healthcare utilization of the women identified as a victim of IPV, we analysed electronic medical records (EMR) retrospectively in a matched case-control design.

Participants: cases and controls

Participants were selected from respondents of the waiting room survey. Inclusion criteria were women attending general practice, 18 years and older, ever having been in a relationship and having been enrolled for at least one year in the general practice between March 2004 and March 2009. All filled in the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) to identify their abuse status. They signed an informed consent for use of their medical record in the present study.

IPV was assessed with the Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) (Citation5): a validated instrument to measure IPV among women in clinical settings. Women with a positive score (CAS ≥ 7) were classified as abused (cases); those with a score < 7 as non-abused.

Non-abused women were matched to cases, using GP practice, age category, number of children, country of origin (native Dutch or not), and level of education. The level of education was divided into low (no school, primary school, and lower vocational education), middle (middle vocational education) and high (school of higher general secondary education, higher vocational education, and university).

Variables

Medical records of abused and non-abused women were analysed for reasons for encounter and healthcare utilization over a period of five years. In addition, we recorded whether IPV was documented in medical records.

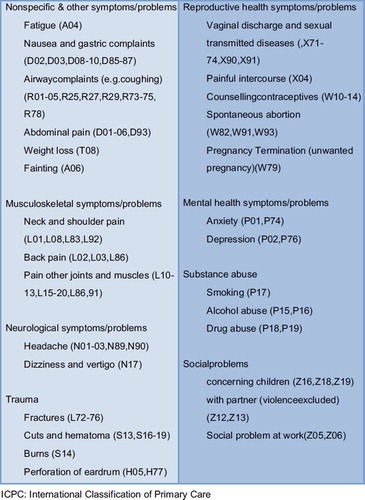

Reasons for encounter. Presented symptoms and problems were clustered according to ICPC-chapters into musculoskeletal problems, neurological problems, trauma, reproductive health problems, mental health problems, social problems, substance abuse and non-specific/other problems () (Citation26).

Healthcare utilization. Healthcare utilization was defined as consultation rate per year, number of referrals for additional diagnostics, medical specialists, and mental healthcare services (psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, abused women's shelter or support service) and number of prescriptions for tranquilizers, antidepressants, painkillers and drugs for digestive symptoms during the previous five years. Visits for preventive healthcare (such as cervical smears, mammograms and nationwide influenza vaccination) were excluded.

Data collection

Data was anonymously collected from the electronic medical records from July to August 2009. All records were reviewed by two independent researchers (EB medical student researcher, MS research assistant). In case of doubt, the classification of the symptoms was discussed in the research group until consensus was reached. The principal investigator (GJP) checked all data and decisions. All visits to the GP, reasons for encounter, prescriptions and referrals were counted.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of healthcare utilization was performed with SPSS version 17.0. We compared the mean number of consultations per patient per year of abused women with non-abused women by an independent sample T-test. Odds ratios (OR) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the numbers of referrals, prescriptions and reasons for encounter were calculated from two-by-two contingency tables. The Pearson chi-square was used. Results with a P value ≤ 0.05 were defined as statistically significant.

Ethical approval

The Ethical Committee of the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre stated that ethical approval was not necessary because of the non-invasive character of the study.

Results

Study population

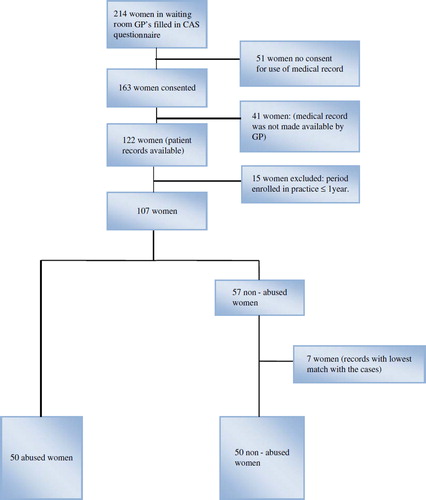

The Composite Abuse Scale (CAS) was completed by 214 women (response rate 63%) consulting GPs in sixteen general practices (Rotterdam) and 163 women (76%) also signed the informed consent to take part in this study on medical records. Despite several attempts, 39 medical records of non-abused women and two of abused women were not available. In total, we received 122 medical records, of which 15 (five abused and 10 non-abused) were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criterion of ≥ 1 year in practice.

In total, EMRs of 50 abused women were matched for general practice, age, number of children, country of origin (native Dutch or not) and level of education to those of 57 controls. Seven records of the controls had no cases in the same general practice and were excluded. describes the selection process of this study.

Finally, the study population consisted of 50 cases and 50 matched controls. provide their characteristics regarding age, country of origin, number of children and educational level. There were no statistically significant differences between both groups ().

Table I. Characteristics of the study group of abused and non-abused women.

Presented problems and healthcare utilization

Consultation rate. The mean consultation rate per year of abused women was 6.7 (SD = 4.7) compared to 4.7 (SD = 4.0) of non-abused, a significant difference (95%CI: 0.3–3.7; P = 0.02).

Presented problems. Abused women visited GPs more specific with issues related to the clusters ‘social problems’ (OR = 3.5; 95%CI: 1.2–10.5; P = 0.01), ‘substance abuse’ (OR = 4.6; 95%CI: 0.9–22.7; P = 0.05) and ‘reproductive health problems’ (OR = 3.0; 95%CI: 1.3–6.8; P = 0.009). From the medical records, it became clear that the GP was aware of IPV in 20% of the cases.

Referrals and prescriptions. Numbers of referrals, prescriptions and reasons for encounter are presented in . Abused women were significantly more often referred for specialized additional diagnostics (OR = 3.6; 95%CI: 1.1–12.2; P = 0.03) and to mental healthcare (OR = 2.9; 95%CI: 1.2–7.1; P = 0.02) than non-abused women. They received more often prescriptions for antidepressants compared to non-abused women (OR = 4.1; 95%CI: 1.5–11.6; P = 0.005). No other significant differences were found.

Table II. Numbers of women in general practice and health care utilization with potential risk factors (referrals, prescriptions and reason for encounter) of partner abuse, odds ratio (OR) before the assessment of IPV.

Discussion

Main findings

The main finding of this case-control study is that healthcare utilization of abused women is higher than non-abused women and shows characteristic features. Abused women use antidepressants more frequently and visit the GP almost twice as often, specifically for social problems, substance abuse and reproductive health complaints.

Interpretation

The high percentage of referrals to mental healthcare is consistent with other studies (Citation9,Citation10,Citation20), as abused women are found to suffer from depressive complaints six times more often than non-abused women (Citation6,Citation10). One study in the USA observed a doubling of visits related to mental health among abused women (Citation22). Other studies generally presented more undefined pain complaints in abused women (Citation9,Citation19,Citation21,Citation23), which will lead to an increased use of medical services for additional diagnostics. This is in line with findings in this study.

Remarkably, we did not observe a higher amount of mental health problems in abused women. However, substance abuse is regarded as a mental health problem, which in turn, can lead to a referral. Apart from a small sample, most women in the present study lived in deprived neighbourhoods in Rotterdam, which is known to affect health negatively (Citation27–29), and possibly lead to a higher quantity of mental health and somatic problems (Citation30,Citation31). Additionally, the Second Dutch National Survey of General Practice (2001) has shown that people living in urban areas and people with deficits in social support have more contact with GPs than people living in non-urban areas or people without deficits in social support (Citation32). This covariant may have resulted in a lack of significant differences in nonspecific and other symptoms and problems between IPV victims and controls.

The results of a higher number of reproductive health problems in IPV victims, support the relationship between IPV and an increased need for help for vaginal discharge and pregnancy termination, which has recently been observed in a population-based interview and cohort study (Citation33,Citation34).

In 5 female victims with IPV, 1 was known by the GP. This percentage is higher than the 10% usually described in the literature (Citation4). A likely explanation is that all participating GPs had been trained to recognize IPV in the previous three-to-six years.

Strengths and limitations

A recent Dutch study reported that women with low levels of education were more likely to experience intimate partner violence than women with higher levels of education (Citation35). Indeed, the cohort of women in this study contained more abused women with lower levels of education (26%) compared to non-abused women (12%) and the Dutch population (20.8%) (Citation36). Therefore, it is important to match education between abused and non-abused women to reduce the effect of selection bias. Despite the small sample and real differences in low education for cases and controls, all cases in the present study were adequately matched for education. Independent researchers performed matching and data extraction to reduce observer bias further. Another strength of the present study is that data are not based on interviews with the danger of recall bias and social desirability of answers, but are objectively recorded in patient files.

Case-control studies for this unusually vulnerable group including migrant women are difficult and relatively rare. In this study, both victims of IPV and matched controls were patients from the same practice, thus international classification (ICPC) and referrals were comparable in both groups. We also succeeded in composing a fairly reliable group of controls.

Most IPV victims (80%) were not identified as such by their GP. The effects of IPV on healthcare utilization are very likely to be underestimated.

A limitation of the current study is the exclusion of an unknown number of women due to illiteracy or poor language proficiency. They were not able to fill out the Composite Abuse Scale and did not take part in this study.

Equally, the non-response of GPs to make all medical records available despite several attempts is an important limitation. This has led to a relatively low number of controls, and hampered to match one IPV case with two controls. As such, the total number of cases in this study is relatively low. Enlargement of the study group might have led to more pronounced differences, in particular for nonspecific symptoms and traumas.

Implications

The typical pattern of healthcare utilization in women with IPV found in this study should alert general practitioners to consider and inquire about intimate partner abuse. Most IPV victims (80%) were not identified as such by their GP. Training on this topic has proved to be an effective method to increase medical professionals’ awareness of IPV (Citation27).

Although several studies observed more visits to mental health services of abused compared to non-abused women, the usual support given by regular mental healthcare institutions does not always fulfil the needs of the victimized women (Citation37,Citation38). It has, therefore, been hypothesized, that victimised women might benefit more from an informal support system, such as women's advocates rather than institutionalized support (Citation38). An easily accessible intervention programme provided in an informal way, is therefore, fully recommended to support abused women.

Half of the abused women in the present study were of immigrant origin. A very important finding is that migrants suffer more frequently from severe depression than native women. A cross-sectional study among migrant and native women in primary care has confirmed a higher likelihood of IPV among migrants compared to natives (Citation6). Interestingly, migrant women are also known to be more vulnerable to die because of IPV (Citation39). As a consequence, healthcare workers need to be very attentive to depression and IPV in migrant women.

Conclusion

In conclusion, abused women in primary care exhibit more social problems, problems with substance abuse and reproductive health problems. They use antidepressants more frequently and are more often referred to mental healthcare and for additional diagnostics than non-abused women. This typical pattern of healthcare utilization could alert general practitioners to inquire about partner abuse in the past.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all 25 participating GPs for their generous cooperation to the study, Margriet Straver, research assistant and Hans Bor, statistician (Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Department of Primary and Community Care) for statistical advice.

Funding: Financial support was given by the City of Rotterdam Public Health Service (GGD), Kinderpostzegelfonds (Children's Stamp Fund) and Stichting Volkskracht.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Jones AS, Dienemann J, Schollenberger J, Kub J, O’Campo P, Gielen AC, . Long-term costs of intimate partner violence in a sample of female HMO enrollees. Women's Health Issues 2006;16:252–61.

- Vos T, Astbury J, Piers LS, Magnum A, Heenan M, Stanley L, . Measuring of the impact on intimate partner violence on the health of women in Victoria, Australia. Bulletin of the WHO 2006;84:739–44.

- Bradley F, Smith M, Long J, O’Dowd T. Reported frequency of domestic violence: cross sectional survey of women attending general practice. Br Med J. 2002;324:271.

- Richardson J, Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Chung WS, Moorey S, Feder G. Identifying domestic violence: Cross sectional study in primary care. Br Med J. 2002;324:274.

- Hegarty KL, Bush R. Prevalence and associations of partner abuse in women attending general practice: A cross-sectional survey. Aust N Z J Public Health 2002;26:437–42.

- Prosman G, Jansen SJC, Lo Fo Wong SH, Lagro-Janssen ALM. Prevalence of intimate partner violence among migrant and native women attending general practice and the association between intimate partner violence and depression. Fam Pract. 2011;0:1–5.

- Coker AL, Davis KE, Arias I, Desai S, Sanderson M, Brandt HM, . Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women. Am J Prev Med. 2002;23:260–8.

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet 2002;359:1331–6.

- Lo Fo Wong S, Wester F, Mol S, Romkens R, Lagro-Janssen T. Utilisation of health care by women who have suffered abuse: A descriptive study on medical records in family practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:396–400.

- Hegarty K, Gunn J, Chondros P, Small R. Association between depression and abuse by partners of women attending general practice: Descriptive, cross sectional survey. Br Med J. 2004;328:621–4.

- Hegarty K, Gunn J, Chondros P, Taft A. Physical and social predictors of partner abuse in women attending general practice: A cross-sectional study. Br Med J. 2008;58:484–7.

- Wester W, Lo Fo Wong S, Lagro-Janssen AL. What do abused women expect from their family physicians? A qualitative study among women in shelter homes. Women & Health 2007;45: 105–19.

- Lo Fo WS, Wester F, Mol S, Romkens R, Hezemans D, Lagro-Janssen T. Talking matters: abused women's views on disclosure of partner abuse to the family doctor and its role in handling the abuse situation. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:386–94.

- Ramsey J, Richardson J, Carter YH, Davidson LL, Feder G. Should health professionals screen for domestic violence? Systematic Review. Br Med J. 2002;325:314–8.

- Hegarty KL, Taft AJ. Overcoming the barriers to disclosure and inquiry of partner abuse for women attending general practice. Aust N Z J Public Health 2001;25:433–7.

- Romans SE, Cohen MM, Forte T, Du Mont J, Hyman I. Gender and psychotropic medication use: The role of intimate partner violence. Prev Med 2008; 46:615–21.

- Campbell J, Jones A, Dienemann J, Kub J, Schollenberger J, O’Campo P, . Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1157–63.

- Coker A, Smith P, Bethea L, King M, McKeown R. Physical health consequences of physical and psychological intimate partner violence. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:451–7.

- Leserman J, Drossman DA. Relationship of abuse history to functional gastrointestinal disorders and symptoms: Some possible mediating factors. Trauma Violence Abuse 2007;8:331–43.

- Ulrich YC, Cain KC, Sugg NK, Rivara FP, Rubanowice DM, Thompson RS. Medical care utilization patterns in women with diagnosed domestic violence. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:9–15.

- Wuest J, Merritt-Gray M, Ford-Gilboe M, Lent, B, Varcoe C, Campbell JC. Chronic pain in women survivors of intimate partner violence. J Pain 2008;9, 11:1049–57.

- Rivara FP, Anderson ML, Fishman P, Bonomi AE, Reid RJ, Carrell D, . Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32,2:89–96.

- Vest JR, Catlin TK, Chen JJ, Brownson RC. Multistate analysis of factors associated with intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:156–64.

- Fanslow J, Robinson E. Violence against women in New Zealand: Prevalence and health consequences. NZ Med J. 2004;117:1173.

- Hamberg K, Johansson EE, Lindgren G. ‘I was always on guard’—an exploration of woman abuse in a group of women with musculoskeletal pain. Fam Pract. 1999;16:238–44.

- Boersma JJ, Gebels RS, Lamberts H. ICPC (International Classification of Primary Care) Short Titles. Utrecht: NHG; 1995.

- Lo Fo Wong S, Wester F, Mol SS, Lagro-Janssen TL. Increased awareness of intimate partner abuse after training: A randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:249–57.

- Wilkinson R, Marmot M. The solid facts. Copenhagen: World Health Organisation; 2003.

- Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet 2005;365:1099–104.

- Olfson M, Shea S, Feder A, Fuentes M, Nomura Y, Gameroff M, . Prevalence of anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders in an urban general medicine practice. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:876–83.

- Stirling AM, Wilson P, McConnachie A. Deprivation, psychological distress, and consultation length in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51:456–60.

- Linden MW van, Westert GP, Bakker DH de, Schellevis, FG. Tweede Nationale Studie naar ziekten en verrichtingen in de huisartspraktijk. Klachten en aandoeningen in de bevolking en in de huisartspraktijk. Utrecht/Bilthoven: NIVEL/RIVM; 2004.

- Fanslow J, Silva M, Whitehead A, Robinson E. Pregnancy outcomes and intimate partner violence in New Zealand. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48:391–7.

- Pels T, Lünneman K, Steketee M. Opvoeden na partnergeweld. Assen: van Gorcum, 2011:46–50.

- Statistics Netherlands. http://www.cbs.nl (accessed September 2010).

- Taft AJ, Watson LF. Termination of pregnancy: associations with partner violence and other factors in a national cohort of young Australian women. Aust N Z J Public Health 2007;31:135–42.

- Coker AL, Smith PH, Thompson MP, McKeown RE, Bethea L, Davis KE. Social support protects against the negative effects of partner violence on mental health. J Women's Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11;5:465–76.

- Ramsay J, Carter Y, Davidson L, Dunne D, Eldridge S, Hegarty K, . Advocacy interventions to reduce or eliminate violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience intimate partner abuse. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, 3:CD005043.

- Vives-Cases C, Gil-Gonzalez D, Ruiz-Perez I, Escribà-Aqüir V, Plazaola-Castano J, Montero-Pinar MI, . Identifying socio demographic differences in intimate partner violence among immigrant and native women in Spain: A cross-sectional study. Prev Med. 2010;51:85–7.