ABSTRACT

Family medicine teachers require specific educational skills. A framework for their professional development is essential for future development of the discipline in Europe. EURACT developed a framework on educational expertise, and subsequently applied it in a curriculum of teaching-skills courses of various levels. The aim of this article is to describe the development of the teaching framework, and of an international three-level course programme for ‘teaching-the-teachers’. Furthermore, we describe our experiences and lessons learned, in particular with regard to the level-three programme for proficient teachers, which was new. We conclude that it is possible to develop a theoretical framework of family medicine teaching expertise and to apply it in an international high-level educational programme for future experts in family medicine education. Research evidence of the usefulness of this approach is needed, and the threats for its further development into a sustainable activity are its high teacher/student ratio associated with relatively high costs and difficulties in recruiting suitable participants.

KEY MESSAGES

A framework of teaching skills for family medicine ranging from novice to expert was developed in a document.

This framework was used as a theoretical background for a series of courses, adapted at each level of expertise.

The result is a sustainable programme for teaching experts for family medicine teachers at different levels of expertise.

Introduction

In most European countries, family medicine is a fundamental part of the healthcare system. The European Union has built it into its healthcare policies and it is being developed by non-member states as a means of providing cost-efficient healthcare.[Citation1] However, current EU legislation, whilst describing the length, place and supervision of specialty training, does not describe the skills required for family doctors in the EU.

Family medicine is characterized by its specific set of knowledge, skills and attitudes. Their detailed description was developed and published by the European Academy of Teachers in General Practice/Family Medicine (EURACT),[Citation2] based on the fundamental characteristics of the discipline of general practice published by Wonca Europe.[Citation3]

The delivery of high quality of patient care is impossible without high quality training programmes.[Citation4] Only skilled GP teachers can provide the practice-based education required, at a sufficiently high level.[Citation5,Citation6] Practice-based training is essential to learn family medicine. Lack of teaching competencies of those family doctors who act as trainers is a crucial deficit in this field.[Citation7]

There is a great variation in the way family physicians are trained across Europe that sometimes raises concerns.[Citation8,Citation9] EURACT has as its aim to foster and maintain high standards of care in European general practice by promoting general practice as a discipline through learning and teaching in Europe. Harmonizing the quality of teaching throughout Europe will help achieve this.[Citation10] EURACT has developed a number of teaching skills courses to assist the further professional development of practising family doctor teachers.[Citation11] They were designed to be applicable to teachers in all European countries and aimed at family doctors who are just beginning their teaching career.

These courses for new teachers continue to run all over Europe, but there is little provision for further development of teaching skills. EURACT therefore, decided to survey the perceived learning needs of both new and of experienced teachers of family medicine with the intention of developing an integrated programme of teacher development. The survey identified learning needs in both groups. The needs were different with some overlap.[Citation12]

The aim of this article is to describe a model of targeted training of teaching skills in the field of family medicine in a European setting and based on the expertise model developed by an international author group.

Developing a framework for teaching-skills training in family medicine

The Dreyfus model

The expertise model described by the Dreyfus brothers looks at the differences between novices and experts in acquiring complex skills.[Citation13] The model describes five stages of expertise: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert. It can be used as a basis for the development of a theoretical framework for the development of a series of teaching activities, adapted to different levels of expertise in teachers. This educational model has been used extensively in nursing education, particularly in the United States, and can be developed in almost any educational field.[Citation14–16] The key to understanding the Dreyfus expertise model is to realize that teachers work differently depending on their level of expertise. For example, novices ‘will have little or no conception of dealing with complexity,’ whereas experts have a ‘holistic grasp of complex situations.’

Developing a Framework document for family medicine teaching-skills training

Adapting The Dreyfus model has never been applied to the teaching-skills training of family medicine teachers. Under the leadership of EURACT, an international collaboration was established—involving several institutions and organizations from different European countries—with the intention of developing a European programme of GP skills-teaching based on different levels of teaching expertise. As a first step, a European framework document on teaching skills was developed to serve as a theoretical background for the educational activities.[Citation17]

In the first phase of the project, the application of the Dreyfus model was discussed through a series of meetings. The discussions highlighted that the characteristics of each of the stages of expertise need to be clearly defined for a GP teaching setting. It was decided to leave out the stage ‘advanced beginner’ as its characteristics appeared to be very similar to and to overlap with the stage of ‘competent’ when applied to teaching skills in family medicine.

The competencies for family medicine teaching were derived from a number of sources in medical education literature.[Citation2,Citation9,Citation18] Another important source of information was a survey assessing the educational needs of teachers in Europe. Family doctor trainers from 15 countries were invited to take part in the study. The results of this research have been published elsewhere.[Citation19]

The document that was developed through this process used a four-stage model of teaching expertise (novice, competent, proficient, and expert). This was discussed at an invitational conference of experts in family medicine education, in EURACT Council meetings and at a workshop at the Wonca Europe conference in 2012. A partnership project plan was agreed with six national organizations of family medicine and with EURACT to test this process over two years. If the process proved successful, it could then be suggested to all European countries.

Developing a course curriculum for family medicine teaching-skills training

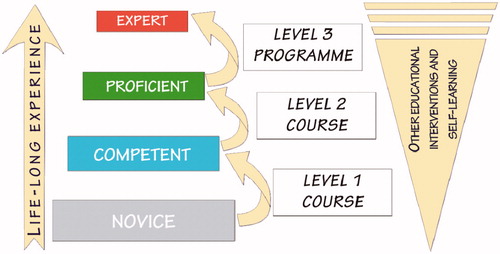

After the framework document had been approved by the EURACT Council, a series of courses were developed to support its application. The model of such a teaching curriculum as part of life-long educational expertise development is demonstrated in .

Three sets of courses were developed: for novice teachers, competent teachers, and proficient teachers, respectively. Each course was aimed to enable participants to move to the next level of teaching expertise. The participants of level one and two courses were provided with the teaching resources needed to rerun the course in their home country.

The level one course for novice teachers was designed as a series of six three-hour (half-day) modules, which can stand-alone or be used in combinations. The content included educational theory and its applicability in general practice, principles of programme design, variety of teaching methods, personal learning styles and plans, formative and summative assessment, and organizational requirements for teaching practices.

The level two course for competent teachers was organized as a series of full-day modules. Participants were able to choose three from four modules in a course lasting three days. The subjects were small group leadership and facilitation, managing problem trainees, teaching from the consultation, and translation of the curriculum to the educational programme.

The level three programme for proficient teachers consisted of two taught parts separated by several months of self-directed study. The term ‘programme’ instead of ‘course’ at level three was used deliberately to stress the expectation that it required self-directed learning. The first part of the course was aimed at developing the participants’ ideas for an educational project. After their return home, the participants had to prepare a detailed plan for a teaching module of their own. Each participant was required to identify and recruit a senior colleague as a mentor to support him or her in completing the programme. Their plans were presented during the second taught part of the programme. Participants had to prepare a 4000-word report on their activity, which was a prerequisite for completion of the course.

Outcomes

The framework document

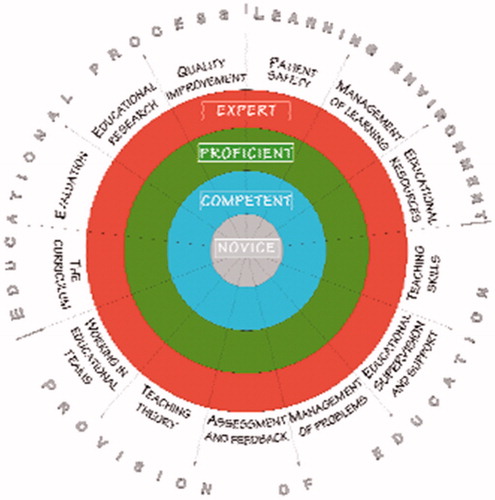

The framework document describes and defines 13 domains of competence at each of the four levels of expertise, giving 52 descriptors of teaching expertise. The 13 domains of competence are grouped into three categories of teaching activity, i.e. learning environment, provision of education, and educational process (). shows an example of how this is done in one domain.

Table 1. Example of description of levels of expertise on a domain of ‘Learning environment’.

Courses

Novice teachers. The level one course was held over six three-hour modules in Turkey in May 2013, with 35 novice teachers from this country and six teachers participating.

Competent teachers. The three-day level two course was held in Ljubljana in October 2013 for an international audience of 16 participants, two from the Czech Republic, Denmark, Greece, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, and Turkey. Six teachers ran the course.

Proficient teachers. Fourteen participants from the same countries as in the level two course applied for the programme and all attended its two educational meetings in Portugal. The same teachers as in the level two course were the faculty of the programme. Eleven participants developed and executed their projects; 10 of the 13 domains of the framework were involved in their projects. Participants from eight European countries (Czech Republic, Denmark, Greece, Malta, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, and Turkey) have successfully completed the programme. An overview is presented in .

Table 2. Basic data about the reports.

Self-evaluation

In the evaluation of all of the courses, participants stressed the value of the inspiration gained from the teachers and other participants. They also appreciated the constructive and friendly atmosphere of the courses.

In the evaluation of the level three programme, the participants also valued the support of their mentors. The programme flexibility allowed them to adjust their learning to their real needs and local circumstances. They also pointed out that the high level of self-responsibility for the rhythm, speed and timing of their programme activities allowed them to combine rather extensive learning with other professional and private duties. Their reports included exciting ideas about future educational activities in Europe, ranging from developing an assessment tool, to developing a nationwide programme for the development of departments of family medicine.

Discussion

The framework document

The idea behind the project was to work towards the harmonization of medical education in family medicine in Europe, which is one of the key goals of EURACT.[Citation19,Citation20] The 13 domains of teachers’ expertise in the framework provides a comprehensive description of the skills needed as a GP teacher. Not every teacher will need to be an expert in all 13 domains to the same level. For example, a university fellow, with little direct practice-based teaching may need to perform as an expert in educational research or teaching theory, whereas a practice-based teacher should master teaching skills, particularly in one-to-one education. Some teachers will develop considerable expertise and may become expert in a very narrow field of general practice education, and others may wish to remain at a level of proficiency over a broader area of activity. No one will have the same level of expertise in all educational domains as a teacher.

Not every member of a teaching organization will have the same level of expertise in all domains. Teachers who manage departments or programmes have to know the strengths of staff members and ensure a balance of talent so that the organization has all types of expertise at its disposal and to develop a strategy of supporting the educational development of their own teachers in areas of expertise to suit the needs of the organization.

The curriculum of family medicine teaching-skills training

The three-level course curriculum serves as an illustration of how the expertise framework can be applied in a practical situation. There are already some reports about faculty development in general practice and courses for the teachers in family medicine.[Citation11,Citation21–23]

EURACT has so far developed several educational courses for teachers on different levels, where more than 1500 trainers participated.[Citation24] The benefit of the project is to help participants to move along a trajectory of professional development as a teacher in a structured way. It enables them to benchmark their level of teaching expertise against a European standard and plan their personal development as teachers accordingly.

The level three programme is a new product, aimed at the future educational leaders of family medicine in European countries. It is pitched at the level of a Masters module, and could be developed into a ‘European Master’ in the future. The participants of this course have developed activities that range from basic to more complex ones. The development of these activities required the development and application of a high level of teaching expertise.

Reflections

The ‘framework for continuing educational development of trainers in general practice in Europe’ aims to make a step forward to harmonizing teaching expertise across Europe. It could be used as guidance for personal development plans for individual family medicine teachers and for heads of faculty to design a strategy for faculty development.[Citation17]

The courses that have been developed are just a few steps in this development. It is clear that simply participating in courses will not convert a novice to an expert. The knowledge, skills and behaviours learnt will have to be integrated into the personal work as a teacher in the home context, and continuously developed.

Our series of international courses is a model that can be used on a European scale, also for countries with a longstanding experience in training of family medicine. Research evidence of usefulness of this approach is still needed, but the feedback from the course participants is hopeful in this regard. The threats for this activity are its high teacher/student ratio, giving rise to relatively high costs and difficulties in recruiting suitable participants. Furthermore, the issue of standards regarding accreditation of teachers in family medicine in Europe and quality control and accreditation of courses, organized at local levels, needs to be addressed in the future. We also need to seek for efficient financing to support wide, European implementation of the courses. Until now, it was possible mainly due to substantial project investment, supported by the EU Leonardo da Vinci Programme. Further development is a challenge for the whole European general practice community and even more widely for European healthcare systems.

Conclusion

The main lesson learnt from this activity is that it is possible to develop a theoretical framework of family medicine teaching expertise and to apply it in an international high-level educational programme for future experts in family medicine education. We believe and hope that the activity can be developed further in a sustainable way. Research evidence of usefulness of this approach is still needed. Finding sufficient financial support for this activity is another challenge.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Schäfer W, Groenewegen PP, Hansen J, et al. Priorities for health services research in primary care. Qual Prim Care. 2011;19:77–83.

- EURACT: The European Academy of Teachers in General Practice [Internet]. Leuven: The EURACT Educational Agenda, 2005 [cited 2015 Aug 10]. Available from: http://www.euract.eu/official-documents/finish/3officialdocuments/93-euract-educational-agenda.

- Wonca Europe [Internet]. Ljubljana: the European definition of general practice/family medicine, 2005 edition. [cited 2015 Aug 10]. Available from: http://woncaeurope.org/content/european-definition-general-practicefamily-medicine-short-version.

- Leach DC, Philibert I. High-quality learning for high-quality health care. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;296:1132–1134.

- Sutkin G, Wagner E, Harris I, et al. What makes a good clinical teacher in Medicine? A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2008;83:452–466.

- Srinivasan M, Meyers F, Pratt D, et al. Teaching as a competency: Competencies for medical educators. Acad Med. 2011; 86:1211–1220.

- Brekke M, Carelli F, Zarbailov N, et al. Undergraduate medical education in general practice/family medicine throughout Europe—a descriptive study. BMC Med Edu. 2013;13:157.

- Oleszczyk M, Svab I, Seifert B, et al. Family medicine in post-communist Europe needs a boost. Exploring the position of family medicine in healthcare systems of Central and Eastern Europe and Russia. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:15.

- Sammut MR, Lindh M, Rindlisbacher B. Funding of vocational training programmes for general practice/family medicine in Europe. Eur J Gen Pract. 2008;14: 83–88.

- Tandeter H, Carelli F, Timonen M, et al. A ‘minimal core curriculum’ for family medicine in undergraduate medical education: a European Delphi survey among EURACT representatives. Eur J Gen Pract. 2011; 17:217–220.

- Bulc M, Švab I, Radić S, et al. Faculty development for teachers of family medicine in Europe: reflections on 16 years’ experience with the international Bled course. Eur J Gen Pract. 2009;15:69–73.

- Guldal D, Windak A, Maagaard R, et al. Educational expectations of GP trainers. A EURACT needs analysis. Eur J Gen Pract. 2012;18:233–237.

- Dreyfus H, Dreyfus S. Mind over machine. New York: The Free Press; 1988.

- Pena A. The Dreyfus model of clinical problem-solving skills acquisition: a critical perspective. Med Edu Online [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2014 Mar 30] 4846. DOI: 10.3402/meo.v15i0.4846. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2887319/pdf/MEO-15-4846.pdf.

- Wijesinha SS, Kirby CN, Tasker C, et al. GPs as a medical educator. Aust Fam Physician. 2008;37:684–688.

- Grant A, Robling M. Introducing undergraduate medical teaching into general practice: an action research study. Med Teach. 2006;28:e192–e197.

- EURACT: The European Academy of Teachers in General Practice [Internet]. Kraków: Framework for continuous educational development of trainers in general practice in Europe. [cited 2014 Dec 11]. Available from: http://www.euract.eu/official-documents/finish/3-official-documents/241-framework-for-continuing-educational-development-of-trainers-in-general-practice-in-europe-cedingp.

- Allen J, Price E, Švab I, et al. EURACT: European academy of teachers in general practice and family medicine. Eur J Gen Pract. 2012;18:124–125.

- Windak A. Harmonizing general practice teachers’ development across Europe. Eur J Gen Pract. 2012;18:77–78.

- Seifert B, Svab I, Madis T, et al. Perspective of family medicine in Central and Eastern Europe. Fam Pract. 2008;25:113–118.

- Herrmann M, Lichte T, Von Unger H, et al. Faculty development in general practice in Germany: experiances, evaluations, and persepctives. Med Teach. 2007;29:219–224.

- Waters M, Wall D. Educational CPD: How UK GP trainers develop themsevles as teachers. Med Teach. 2008;30: e250–e259.

- London Deanery [Internet]. London: Professional development framework for supervisors in the London Deanery, 2012 [cited 2014 Dec 11]. Available from: http://www.faculty.londondeanery.ac.uk/professional-deve-lopment-framework-for-supervisors

- Vrcić-Keglević M, Jaksić Z. International course training of teachers in general/family practice: 20 years of experience. Lijec Vjesn. 2002;124:S2:36–39.