Abstract

Context: Periplaneta americana L. (Dictyoptera; Blattaria) has been traditional used to treat ulcers, burns and heart disease in southwestern China. Recent reports indicate that P. americana can be used as an alternative medicine in therapy of ulcerative colitis, but the mechanism involved remains obscure.

Objective: This study investigated the therapeutic effect of P. americana extract (PAE) in rat colitis and elucidated its potential mechanism.

Materials and methods: Dinitrochlorobenzene and acetic acid-induced colitis rat model was applied. Colitis rats were treated with PAE for 10 d and estimated disease activity index daily. Rectal inflammation was assessed by myeloperoxidase activity and histological changes. Another colitis rats were treated with PAE for 4 d, meanwhile gavage with Escherichia coli labelled with green fluorescent protein. Mesenteric lymph nodes, colon, liver, spleen and kidney were harvested for bacteria culture. PAE was suspended in distilled water then partitioned with ethyl acetate and n-butanol to obtain ethyl acetate fraction, n-butanol fraction and water fraction, respectively. Fibroblasts proliferation and collagen accumulation of each fraction was determined.

Results: PAE treatment reduced the severity of colitis and tissue myeloperoxidase accumulation (p < 0.001). Also, PAE at 80 mg/kg significantly inhibited labelled E. coli from translocating to distant organs, especially to MLN and liver. Additionally, PAE significantly stimulated fibroblasts proliferation (126.9%) and collagen accumulation (130.8%) for 48 h incubation. Among the partitions, ethyl acetate fraction generally had higher fibroblast viability enhanced-activity.

Conclusions: PAE can protect against ulcerative colitis and this protection is attributed to anti-inflammation and fibroblasts viability.

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a common chronic idiopathic inflammatory disease in large intestine that occurs usually in the rectum and lower part of the colon and even the entire colon, causing diarrhoea, bloody purulent stool, bellyache and tenesmus. UC common complications include proctitis, rectal abscess, anal fissure, enterobrosis, ileus as well as colon cancer (Hanauer Citation2006). When inflammatory process involves rectum, genitourinary diseases may be caused via intestinal bacterial translocation (Shafik Citation1984; Jin et al. Citation2003). Several traditional agents, like 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) and corticosteroids, have been widely used to treat UC, but many side effects of these drugs are discovered and are considered as major problems (Xu et al. Citation2004).

Periplaneta americana L., or called cockroach, first recorded in an ancient Chinese pharmacopeia “Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing”. Periplaneta americana has been extensively studied for its certain special substances and defence mechanisms to resist environmental threats, which have contributed to its evolutionary presence for more than 300 million years. Kangfuxin solution, a crude ethanol extract from dried P. americana whole body, contains polyols, glycosaminoglycan, polypeptides, 18 kinds of amino acids and some other active constitutions (Yan & Fang Citation1991), and has been widely used in China to treat trauma, burns (Fang Citation2012), oral cavity ulcer (Guo et al. Citation2011), cervical erosion (Cui & Zhang Citation2013), ulcerative colitis (Sun Citation2015) and various types of gastrointestinal ulcers and has no side effects (Li et al. Citation1987) since 1985. Liu et al. (Citation2012) reported that Kangfuxin against gastric ulcer probably by promoting the production and expression of local basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and tumor necrosis factor β (TNF-β). Zhen et al. (Citation2008) found Kangfuxin can attenuate diarrhoea and gross bleeding in dextran sulphate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis rats by inhibiting the expression of matrix metalloproteins (MMPs)-3 and MMPs-13. However, the chemical composition of Kangfuxin is a complex, its mechanisms of mucosal healing effect are not fully clear.

In the present work, we investigated whether PAE can accelerate the healing process in dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) and acetic acid (AA)-induced ulcerative colitis rat, and whether PAE can inhibit intestinal bacterial translocation in vivo. Furthermore, in order to get an insight into the mechanism of actions of PAE, we investigated its effects on NIH 3T3 fibroblasts proliferation and collagen accumulation in vitro.

Material and methods

Chemicals and reagents

The reference standards l-alanine, bovine serum albumin, mannitol and chondroitin sulphate were purchased from National Institute for Food and Drug Control (Beijing, China). Sulphasalazine (SASP) was purchased from Shanghai SINE Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). DNCB was purchased from Xiya Chemical industry Co., Ltd (Shangdong, China). The MPO and hydroxyproline kits were purchased from Jiancheng Biology Engineering Institute Co., Ltd (Nanjing, China). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Tianhang Biological Technology Stock Co., Ltd (Zhejiang, China). High-glucose DMEM medium and MTT was purchased from Gibco, Invitrogen Co. (Carlsbad, CA). Except where indicated, all other chemicals were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

Experimental animals and green fluorescent protein-labelled E. coli

Male Sprague–Dawley rats weighing 250–300 g were purchased from Jiangsu University Laboratory animal research center (Jiangsu, China). All animals were housed 8/cage and fed by standard laboratory chow diet of 20 g per rat and water in the animal room with regulated temperature of 22 ± 1 °C and humidity of 60 ± 10%, kept on a 12 h dark/light cycles for one week acclimation period. All animal experiments were conducted under university guideline. All procedures in the manuscript were reviewed in advance by the Laboratory Animal Management Committee of Jiangsu University.

Green fluorescent protein labelled E. coli (GFP-uv E. coli) was obtained from Wuhan institute of virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. GFP-uv E. coli containing an ampicillin resistance gene as a selectable marker and GFP gene as a track gene, was incubated in LB medium with ampicillin (50 mg/L) at 37 °C until bacterial suspension concentration was 8 × 108 CFU/mL based on the calibration curve of CFU concentration versus optical density (OD at 600 nm).

Preparation of P. americana extract (PAE)

Dried adult P. americana was purchased from Yunnan, China, and expertly examined by Professor Jun Chen at Jiangsu University. Dried whole body was extracted with ethanol as previously described (Geng Citation2010) with a few modifications. Briefly, the powder of P. americana was soaked in 85% ethanol (1:7 w/v) overnight, then extracted three times with 85% ethanol at 60–65 °C for 2, 1.5 and 1 h, respectively. Supernatant was pooled, filtered, evaporated under reduced pressure and lyophilized into dry solid PAE, which was stored at −20 °C until required.

Properties of PAE

The amino acids content was determined by Nihydrin Colorimetriy (Moore & Stein Citation1954) using l-alanine as a standard. The polypeptide content was carried out by Bradford (Citation1976) method using bovine serum albumin as a standard. The polyols content was determined by colorimetric method (Bok & Demain Citation1977) using mannitol as a standard. The glycosaminoglycan (GAG) content was determined by Alcian Blue staining method (Gold Citation1979) using chondroitin sulphate (CS) as a standard.

DNCB and AA-induced colitis in rats and PAE treatment

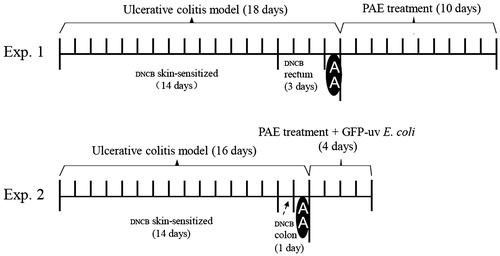

A total of 42 rats were skin-sensitized to their shaved napes at daily basis with 2% (w/v) DNCB solution in acetone (0.3 mL for each) for 14 d. On the 15th day, a silicone catheter (3 mm in diameter) was carefully inserted into rat rectum (2.5 cm in depth from the anus), and then 0.25 mL 1% (w/v) DNCB in 50:50 ethanol–water solution was infused one time per day from days 15 to 17. On the 18th day, 0.5 mL 8% AA was infused in the same site for each rat, then 2.5 mL normal saline was infused to wash out AA () (Glick & Falchuk Citation1981; Jiang & Cui Citation2000). After modeled, animals appeared less activity, colour bleak, appetite loss, loose stools or gross bleeding, as well as anal irrigation.

Figure 1. Experimental protocols of the study. (A) Study with dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) and acetic acid (AA)-induced ulcerative colitis rats; (B) study with bacterial translocation of colitis rats.

In enema preparation, PAE or SASP was dissolved in 0.9% saline, and then mixed with lanolin and egg yolk oil to get drug-containing ointment. Or only normal saline was mixed with lanolin and egg yolk oil to get vehicle ointment.

To evaluate the effect of PAE on UC, rats were divided into six groups randomly (n = 7 in each group): vehicle group, model group, positive control group and three PAE groups (P1, P2 and P3). The first and the second group were given with vehicle ointment enemas. Other four groups were administrated as SASP enemas (250 mg/kg/d) or PAE (P1, P2 and P3) enemas (20, 40 and 80 mg/kg/d) for 10 d, respectively.

Assessment of disease activity index (DAI)

The weight loss, stool consistency and occult/gross bleeding of 42 rats were recorded daily. DIA score was evaluated by combining scores based on the scale described previously () (Cho et al. Citation2011).

Table 1. Evaluation of disease activity index (DIA).

Histology

At the end of the experiment, all rats were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation and the rectum samples were collected immediately. Each tissue specimen was grossly examined for the ulcerative lesion, and then representative segments were fixed immediately in 10% formalin. After overnight fixation, segments were embedded in paraffin and stained with haematoxylin & eosin for histopathological analysis.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity assay

MPO is an enzyme found in cells of myeloid origin and has been used extensively as a biochemical marker of granulocyte (mainly neutrophil) infiltration into gastrointestinal tissues (Islam et al. Citation2008). Rectum samples were homogenized in buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl PH 7.4, 0.1 mM EDTA–2Na, 10 mM sucrose, 0.8% NaCl). MPO activity assay of those homogenates was determined by kits according to the instructions of manufacturer.

Bacterial translocation of UC rats

After adaptation period, stools of another 30 rats were cultured on LB agar plates containing 50 mg/L ampicillin overnight at 37 °C. A total of 24 rats without ampicillin-resistant colonies in their stool culture plates were selected and divided into 4 groups randomly (n = 6 in each group): control group, model group and two PAE groups (P1 and P2).

The rats in model, P1 and P2 groups were similarly skin sensitized to 2% DNCB solution for 14 d. On the 15th day, the same silicone catheter was inserted into rat colon with 0.5 mL 0.25% (w/v) DNCB in 50:50 alcohol–water solution. On the 16th day, 2 mL 8% AA was infused into each rat in the same site, then 5 mL normal saline was infused to wash out residual AA. From the 17th to 20th days, the model group was given vehicle ointment enemas and PAE (P1 and P2) groups were given drug-containing ointment enemas (20 and 80 mg/kg/d). Six hours after treatment, they all gavaged with 1 mL 1.5% (w/v) sodium bicarbonate to neutralize gastric acid transiently and subsequently gavaged with 1 mL of 8 × 108 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL GFP-uv E. coli for 4 d ().

All rats were sacrificed by CO2 inhalation at the end of experiments 4 h after gavage of GFP-uv E. coli on the 4th day. The abdomens of rats were washed with 70% alcohol and then opened under sterile condition to allow excision of mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), colon, spleen, kidney and liver.

Approximately 0.2 g of each sample were homogenized in 1 mL sterile saline, then 200 μL homogenates were spread on LB agar plate under sterile condition. After aerobic incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, the number of fluorescence CFUs was counted under UV 540 nm.

NIH 3T3 fibroblasts assay

Cell culture and drug solution

Murine embryo fibroblast (NIH 3T3) were purchased from China Center for Type Culture Collection (Wuhan, China) and cultured in high-glucose DMEM medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS. The cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 in an incubator.

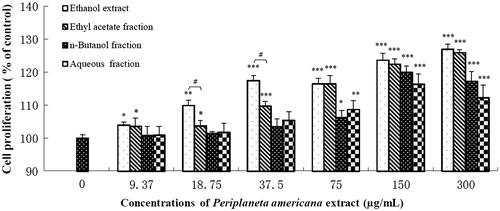

To study fibroblasts activity enhanced effects of PAE components involved, PAE was suspended in distilled water and subsequently partitioned with ethyl acetate and n-butanol to obtain ethyl acetate fraction, n-butanol fraction and aqueous fraction. Every fraction was evaporated and lyophilized to dryness to give 39% (g/g) ethyl acetate fraction, 5% (g/g) n-butanol fraction, 56% (g/g) aqueous fraction (). Each fraction was diluted to a series of concentrations equivalent to the concentrations of PAE (0, 9.37, 18.75, 37.5, 75, 150 and 300 μg/mL).

Table 2. Ingredients of the three fractions of PAE.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation activity was quantified by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. NIH 3T3 fibroblasts were seeded overnight in 96-well plates at 3 × 103 cells per well in 200 μL DMEM with 0.1% (v/v) FBS. Cells were incubated with different concentrations of PAE (0, 9.37, 18.75, 37.5, 75, 150 and 300 μg/mL) at 37 °C for 48 h. Then, 20 μL MTT solution (5 mg/mL in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline) was added directly to each well and incubated at 37 °C for another 3 h. All media were aspirated and replaced by 150 μL of DMSO for 15 min to solubilize formazan crystals. The absorbance of the solution was measured at 570 nm using a spectrophotometer. The absorbance of control group (0 μg/mL) was standardized as 100%.

Collagen content measurement assay

Hydroxyproline is the most abundant amino acid in collagen, which acts as a collagen content index. A hydroxyproline colorimetric method was used to assess the effect of PAE on collagen synthesis in NIH 3T3. Cells were seeded in 24-well plastic chamber at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and grown in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS for 12 h. Then, the media were aspirated and replaced by 500 μL/well DMEM 0.1% FBS containing different concentrations of PAE (0, 18.75, 37.5, 75, 150 and 300 μg/mL) at 37 °C for 48 h. To measure hydroxyproline, cell supernatant was used to detect hydroxyproline. A blank tube (containing sterile distilled water) and a standard tube (containing 5 μg/mL standard hydroxyproline application solution) were prepared following the instruction in hydroxyproline kits. The absorbance of each sample was analyzed at 550 nm by colorimetry.

Statistical analysis

Experiment results were expressed as mean ± SD. For the comparison of different treatment groups, the data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Values of p < 0.05 were considered as significant.

Results

Properties and ingredients of PAE

PAE was a brown dried powder. It smells aromatic and slightly fishy, and it tastes salty and bitter. Dried powder of crude P. americana produced an average PAE yield of 6.4% (g/g). The total amino acid content in PAE was 17.2% (g/g). Total polypeptides content was 1.6% (g/g). The content of polyols and glycosaminoglycan were 36.75% (g/g) and 11.45% (g/g), respectively. According to the departmental standard of ethanol extract of P. americana, amino acid content shall not less than 7.0% (g/g). Quality of PAE followed the department standard protocol (Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, Citation2001) that amino acid content of ethanol P. americana extract should not less than 7.0% (g/g).

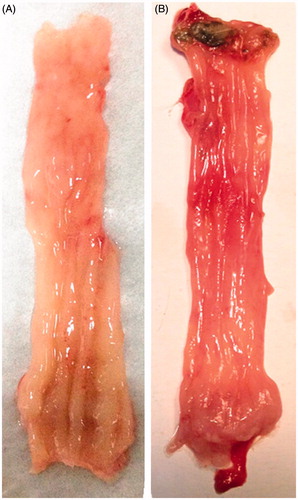

Macroscopic appearance of rectum

No macroscopic damage was observed in control rat. However, DNCB and AA administration caused a significant increase in rectum inflammation including visible hyperaemia, swelling and ulcers ().

Effects of PAE on UC rats

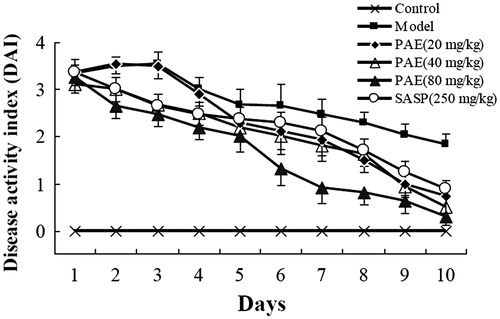

Disease activity index score

A combinatorial DAI was used to evaluate the therapeutic effects of PAE. SASP (250 mg/kg) was used as a positive control. DNCB and AA-induced colitis rats showed clear disease signs including body weight loss, diarrhoea and gross bleeding, which resembled the acute phase of human ulcerative colitis. PAE (20, 40 and 80 mg/kg) treatment dose-dependently ameliorated these disease symptoms and reduced intestinal inflammation. In particular, PAE (80 mg/kg) showed a better therapeutic effect than SASP (250 mg/kg) ().

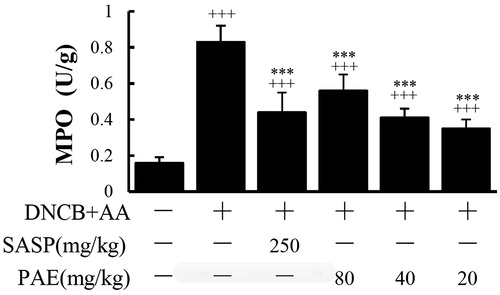

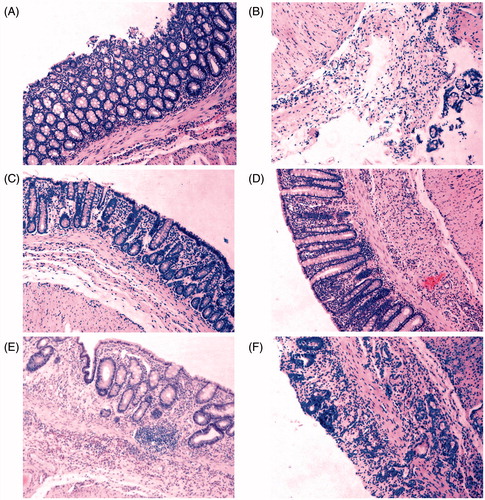

Histopathological results and MPO levels

All harvested rectums were subjected to histological analysis after H&E staining (). DNCB and AA extensively damaged the superficial epithelium and induced visible mucosal inflammation and loss of epithelial cell layer (). In contrast, PAE treatment for 10-d enemas significantly reduced the extent of inflammation and the damage to the surface areas (). Our histopathological findings presented that mechanisms of mucosal protective effect of PAE involved fostering epithelial regeneration and alleviating inflammatory cell infiltration. Thus, rectum inflammation levels were quantitatively estimated by measuring MPO activity in rectum tissue.

Figure 4. Representative H&E staining photomicrographs on rats rectum sections. (A) The vehicle group shows intact crypts structure and epithelial cell layer, normal goblet cells morphology. (B) The model group shows lamina propria damage, epithelial cells loss and intense inflammatory cells infiltration. (C) The sulphasalazine (SASP) (250 mg/kg) group shows regenerated mucosa and crypts and decreased inflammatory reaction. (D) The P. americana extract (PAE) (80 mg/kg) group shows no remarkable inflammatory features with normal crypts structure. (E) The PAE (40 mg/kg) group shows crypts dilation and distortion, fibrosis in lamina propria. (F) The PAE (20 mg/kg) group shows disappearance of crypts, superficial mucosal ulcer and inflammatory cells infiltration in the lamina propria. Magnification was 100×.

MPO levels of the model group was elevated significantly (p < 0.001) upon the control group, which indicated DNCB could induce neutrophil infiltration. PAE resisted the increase of MPO levels in the rectum tissues compared with the model group (p < 0.001) ().

PAE inhibited bacterial translocation

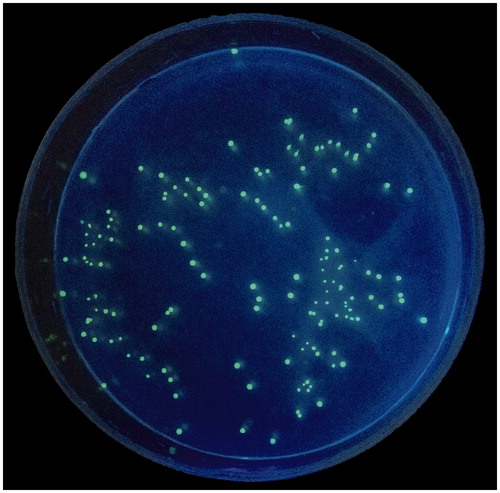

Berg and Garlington (Citation1979) used a term ‘bacterial translocation (BT)’ to describe the passage of viable indigenous bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract to extra intestinal. Failure of the gut barrier in conjunction with liver dysfunction promotes or potentiates multiple-organ failures (Berg Citation1995). Therefore, detection of BT may directly reflect the intestinal barrier function. As mentioned before, we investigated the BT in four groups: control-vehicle + E. coli, DNCB & AA-vehicle + E. coli, DNCB & AA-PAE 20 mg + E. coli and DNCB & AA-PAE 80 mg + E. coli. Each rat was gavaged with GFP-uv E. coli for 4 d, meanwhile treated with or without PAE. Four hour after gavaged GFP-uv E. coli on the 4th day, all rats were sacrificed and MLN, colon, liver, spleen and kidney were harvested and homogenized for labelled E. coli bacterial culture (). showed a cultured sample of fluorescence image of GFP-uv E. coli isolated from UC rat tissue. Our finding showed that acute UC caused intestinal bacteria translocation to MLN, liver, spleen and kidney, whereas PAE markedly prevented BT caused by UC. The number of CFU per 200 μL tissue homogenates was significantly higher of the model group compared with the PAE group, especially in MLN and in colon. It suggested that once intestinal mucosal barrier was damaged, MLN appeared to be more susceptible to BT than did the liver, kidney or spleen. Although vehicle-treated control group rats were also gavaged GFP-uv E. coli, only five and three labelled bacterial colonies were detected from two rat colon tissues, respectively. Other distant organs had no GFP-uv bacteria colonies detected.

Figure 6. A cultured sample of fluorescent image of GFP-uv E. coli isolated from ulcerative colitis rat tissue under an ultraviolet lamp at 540 nm.

Table 3. CFU number of viable GFP-uv E. coli and incidence of bacterial translocation of rats tissues. (n = 6/group).

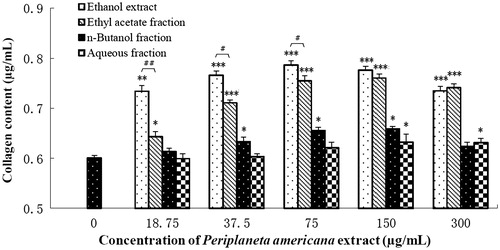

PAE stimulated fibroblasts proliferation and collagen production in vitro

Fibroblasts proliferation is an important step for granulation formation in ulcer healing process. Treatment with PAE for 48 h increased NIH 3T3 proliferation to 126.9% of control at 300 μg/mL (). All the three fractions of PAE dose-dependently increase cell viability and their maximum effect in the following order: ethyl acetate fraction (125.9%) > n-butanol fraction (120%) > aqueous fraction (116.3%). Additionally, PAE and ethyl acetate fraction are statistically equivalent at higher concentrations (75, 150 and 300 μg/mL).

Figure 7. Effects of P. americana extract (PAE) and its three fractions on proliferation of NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 versus the control group. #p < 0.05 versus the PAE group.

Collagen content is an important indicator to evaluate wound healing capabilities. shows that PAE had a positive effect on collagen synthesis and secretion from NIH 3T3 after 48 h incubation. Among the partitions, ethyl acetate fraction had higher collagen synthesis enhanced effect and its data are statistically equivalent to that of PAE at 150 and 300 μg/mL.

Discussion

The integrity of gut mucosa is important to prevent indigenous and exogenous bacteria crossing from intestinal mucosal barrier (Berg Citation1995). UC causes intestinal epithelium injury inducing bacteria translocation to the portal venous system, then to other distant organs. Bacterial translocation may promote multiple-orange failure, leading to some complex syndrome. In 1983, Shafik (Citation1984) first discovered 2–6 sizeable veins, named rectogenital veins, connecting haemorrhoidal plexus in the anal submucosa with the vesicovaginal or vesicoprostatic plexus. These veins are unidirectional, transmitting the anal blood towards the urogenital organs but not in the reverse direction. Jin (Citation2009) pointed out the presence of these communication veins between the anorectum and genitourinary organs could explain some of the recurrent genitourinary diseases, such as non-specific prostatitis, cystitis, vaginitis and cervicitis. Under certain condition, indigenous bacteria from colon or rectum tissue may be translocated to genitourinary organs via portal vein blood, which may cause aforementioned diseases. In the study, we demonstrated PAE significantly protected rectum in UC rats, suggesting that PAE may attenuate potential genitourinary complications coupled with UC.

To confirm intestinal bacterial translocation, some studies had applied enteral feeding of radioisotope- (Pérez-Paramo et al. Citation2000), fluorescein-labelled bacteria (Inamura et al. Citation2003) as well as GFP-labelled bacteria (Song et al. Citation2006). However, the former two have raised some problems associated with possible label dissociation in marked bacteria. While GFP is a stable, simple and useful marker, and not easily loss through passaging process. So we used it to investigate intestinal bacteria translocation. In our study, we showed that PAE prevented intestinal bacterial translocation, and data also suggested that PAE can promote recovery of intestinal barrier in UC.

DNCB functions as a hapten when bound to tissue protein and is capable of eliciting cell-mediated (T-lymphocyte-dependent) immune response (Glick & Falchuk Citation1981). The symptoms and histological features of DNCB-induced rat UC model are similar to those of human UC, but with a short self-limited course of only 2 weeks. In this study, we used a new chronic UC model by DNCB and AA combination, which overcomes the disadvantages of short course of DNCB method and the absence of immunoreactivity in AA method (Jiang et al. 2000). The present work revealed that this UC rat model worked well. Our study adopted enema administration method injecting drug-containing oily ointment into rat rectum directly, thereby improved the drugs adhesion to intestinal mucosa cells. The present work also revealed that ointment enema method worked well. This method can deliver drugs directly to intestinal mucosal lesions with less irritation than aqueous enema, thus improving the medication compliance of rats.

As well known, fibroblasts act as an ‘engineer, builder and administrator’ during wound repair and regeneration process. Fibroblasts synthesize and remodel extracellular matrices (Lekic & McCulloch Citation1996) as well as migrate into myofibroblasts promoting granulation tissue formation (Darby et al. Citation1990). In order to reveal part of mucosal healing mechanisms of PAE, the second block of the present work used an in vitro fibroblast cell model, NIH 3T3, confirmed PAE was able to encourage fibroblasts proliferation and collagen synthesis.

Cockroach is one of the few creatures that having the ability of regenerating lost tissues or organs. To date, some proteins that appear or increase transiently in regenerating Periplaneta legs have been reported. Kubo et al. (Citation1990, Citation1991, Citation1993) purified a 37 kDa sucrose-binding lectin in regenerating cockroach legs, Periplaneta lectin from an adult haemolymph in 1990, then purified a 26 kDa lectin in 1993. Nomura et al (Citation1992) found a protein with a molecular mass of 10 kDa called p10 in the regenerating, and later Kitabayashi et al. (Citation1998) reported the amino acid sequence of p10. Additionally, 18 kinds of amino acids in PAE (Yao Citation1994) are an important material to supply tissue growth. Glutamine (Gln) is the main fuel in the growth and metabolism of intestinal mucosal cells to maintain intestinal mucosal structures and functions, especially under such severe stress as trauma, infection. Gln can also effectively prevent intestinal mucosal atrophy, enhance intestinal cell activity, improve intestinal immune function and attenuate intestinal bacteria and endotoxin translocation (Van der Hulst et al. Citation1993). Arginine can not only promote the proliferation of intestinal mucosa but also directly participate in the body's immune defence and promote wound healing. Furthermore, polyols are important active substance in PAE, including fructose, inositol and mannitol (Chen et al. Citation2009). Mannitol, an effective free radical scavenger, is able to attenuate cerebral ischemia, neuronal damage (Niu et al. Citation2003) and prevent gastric lesions in an osmolality-dependent manner though inhibiting hydroxyl radical formation (Gharzouli et al. Citation2001). Kim et al. (Citation2002) discovered that mannitol can inhibit H. pylori-induced COX-2 expression in gastric epithelial cells. Besides, PAE contains glycosaminoglycan family, mainly heparan sulphate (Dos Santos et al. Citation2006). They play an important role during physiological and pathological conditions including physiological development, wound healing, cancer development, microbial and virus infections, immune response, the functions of glycosaminoglycan family can be attributed to both the core protein and the attached heparan sulphate chains (Qiu & Ding Citation2011). Jiang et al. (Citation2015) isolated and identified 10 chemical compounds from P. americana, from which 4-hydroxy-benzenepropanoic acid has an anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting the release of NO factor, 3,4-dihydro-2-hydro-quinolinone can effectively prevent thrombosis via inhibiting platelet aggregation. Based on these studies, the contents of polypeptides, amino acids, polyols and glycosaminoglycan, were analyzed in the present work. Our results demonstrated that most polypeptides and entire glycosaminoglycan of PAE are distributed to ethyl acetate fraction. Also, ethyl acetate fraction exhibited the best activity in modulating fibroblast functions. Therefore, the acceleration of mucosal healing induced by PAE was associated with polypeptides and glycosaminoglycan. However, we cannot establish whether they were main bioactive components for the treatment of ulcerative colitis.

This was the first time evaluating these four kinds of chemical components as the quality criteria of PAE, which help to provide a better pharmacodynamic understanding of PAE material and provides a theoretical basis for the further development and utilization of P. americana.

Conclusions

PAE is rich in bioactive substances, including amino acids, peptides, polyols and glycosaminoglycan family. In the experimental UC rat model, PAE effectively improves intestinal damage induced by DNCB and AA, decreases intestinal bacteria translocation. The mechanism to mucosal protection of PAE may work through dual functions: (i) anti-inflammatory and (ii) promotion cell proliferation and collagen synthesis. However, the relationship between the pharmacological functions and pharmacodynamic materials contained in PAE is still unclear. If active components work together in a synergistic mode, or which component, if any, is a main bioactive component, remains for further research.

Funding information

This work was supported by a grant of Jiangsu University Academic Degree Graduate Research Innovation Program in 2014 (1291290012).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Degang Ning in Wuhan institute of virology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for providing GFP-uv E. coli.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Berg RD. 1995. Bacterial translocation from the gastrointestinal tract. Trends Microbiol. 3:149–154.

- Berg RD, Garlington AW. 1979. Translocation of certain indigenous bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract to the mesenteric lymph nodes and other organs in a gnotobiotic mouse model. Infect Immun. 23:403–411.

- Bok SH, Demain AL. 1977. An improved colorimetric assay for polyols. Anal Biochem. 81:18–20.

- Bradford MM. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 72:248–254.

- Chinese Phyarmacopoeia Commission. 2001. Kangfuxin Ye quality standard. Drug Standards China. 02:31–32.

- Chen XH, Ran XZ, Sun RS, Shi CM, Su Y, Guo CH, Cheng TM. 2009. Protective effect of an extract from Periplaneta americana on hematopoiesis in irradiated rats. Int J Radiat Biol. 85:607–613.

- Cho E, Shin JS, Noh YS, Cho YW, Hong SJ, Park JH, Lee JY, Lee JY, Lee KT. 2011. Anti-inflammatory effects of methanol extract of Patrinia scabiosaefolia in mice with ulcerative colitis. J Ethnopharmacol. 136:428–435.

- Cui XH, Zhang HP. 2013. Investigation of the clinical effect of microwave combined with Kangfuxin in treatment of severe cervical erosion. Pharm Clin Res. 21:286–288.

- Darby I, Skalli O, Gabbiani G. 1990. Alpha-smooth muscle actin is transiently expressed by myofibroblasts during experimental wound healing. Lab Invest. 63:21–29.

- Dos Santos AV, Onofre GR, Oliveira DM, Machado EA, Allodi S, Silva LC. 2006. Heparan sulfate is the main sulfated glycosaminoglycan species in internal organs of the male cockroach, Periplaneta americana. Micron. 37:41–46.

- Fang GR. 2012. Clinical analysis of 63 cases of Kangfuxin in treatment of limb injury wound. Guide China Med. 10:249–250.

- Geng FN. 2010. Pharmaceutical composition comprising Periplaneta americana or its ethanol extract and a method of using the same for treating inflammations. U.S. Patent Application 12/336,675.

- Gharzouli K, Gharzouli A, Amira S, Khennouf S. 2001. Protective effect of mannitol, glucose-fructose-sucrose-maltose mixture, and natural honey hyperosmolar solutions against ethanol-induced gastric mucosal damage in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 53:175–180.

- Glick M, Falchuk Z. 1981. Dinitrochlorobenzene-induced colitis in the guinea-pig: studies of colonic lamina propria lymphocytes. GUT. 22:120–125.

- Gold EW. 1979. A simple spectrophotometric method for estimating glycosaminoglycan concentrations. Anal Biochem. 99:183–188.

- Guo YY, Lin ZL, Huang RH. 2011. Curative effect analysis of Kangfuxin to recurrent oral ulcer. Guide China Med. 20:2011–2013.

- Hanauer SB. 2006. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 12:S3–S9.

- Inamura T, Miura S, Tsuzuki Y, Hara Y, Hokari R, Ogawa T, Teramoto K, Watanabe C, Kobayashi H, Nagata H, Ishii H. 2003. Alteration of intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes and increased bacterial translocation in a murine model of cirrhosis. Immunol Lett. 90:3–11.

- Islam M, Murata T, Fujisawa M, Nagasaka R, Ushio H, Bari AM, Hori M, Ozaki H. 2008. Anti-inflammatory effects of phytosteryl ferulates in colitis induced by dextran sulphate sodium in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 154:812–824.

- Jiang WX, Luo SL, Wang Y, et al. 2015. Review on investigations related to chemical constituents. J Jinan Univ (Nat Sci Med Ed). 36:294–301.

- Jiang XL, Cui HF. 2000. A new chronic ulcerative colitis model produced by combined methods in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 6:742–746.

- Jin H. 2009. Modern anorectal diseases. Beijing, China: People's Military Medical Publisher and Distributor.

- Jin H, Jing WS, Yang SB, et al. 2003. Study on the correlation between mixed hemorrhoids and prostate disease. Chinese J Coloproctol. 23:4–6.

- Kubo T, Kawasaki K, Natori S. 1990. Sucrose-binding lectin in regenerating cockroach (Periplaneta americana) legs: its purification from adult hemolymph. Insect Biochem. 20:585–591.

- Kubo T, Kawasaki K, Natori S. 1993. Transient appearance and localization of a 26-kDa lectin, a novel member of the Periplaneta lectin family, in regenerating cockroach leg. Dev Biol. 156:381–390.

- Kubo T, Kawasaki K, Nonomura Y, Natori S. 1991. Localization of regenectin in regenerates of American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) legs. Int J Dev Biol. 35:83–90.

- Kim H, Seo JY, Kim KH. 2002. Effect of mannitol on Helicobacter pylori-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in gastric epithelial AGS cells. Pharmacology. 66:182–189.

- Kitabayashi AN, Arai T, Kubo T, Natori S. 1998. Molecular cloning of cDNA for p10, a novel protein that increases in the regenerating legs of Periplaneta americana (American cockroach). Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 28:785–790.

- Lekic P, McCulloch CAG. 1996. Periodontal ligament cell population: the central role of fibroblasts in creating a unique tissue. Anat Rec. 245:327–341.

- Li SN, Li H, Zhang HM, et al. 1987. Study on the ingredients to promote the growth of granulation of Periplaneta americana. Med Pharm Yunnan. 3:018.

- Liu TT, Huang XS, Cheng J, et al. 2012. Study on the mucosal repair mechanisms of Kangfuxin solution in the treatment of acetic acid burn rat gastric ulcer model. Lishizhen Med Mater Med Res. 23:3028–3030.

- Moore S, Stein WH. 1954. A modified ninhydrin reagent for the photometric determination of amino acids and related compounds. J Biol Chem. 211:907–913.

- Niu K, Lin K, Yang C, Lin M. 2003. Protective effects of alpha-tocopherol and mannitol in both circulatory shock and cerebral ischaemia injury in rat heatstroke. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 30:745–751.

- Nomura A, Kawasaki K, Kubo T, Natori S. 1992. Purification and localization of p10, a novel protein that increases in nymphal regenerating legs of Periplaneta americana (American cockroach). Int J Dev Biol. 36:391–398.

- Pérez‐Paramo M, Munoz J, Albillos A, Freile I, Portero F, Santos M, Ortiz-Berrocal J. 2000. Effect of propranolol on the factors promoting bacterial translocation in cirrhotic rats with ascites. Hepatology. 31:43–48.

- Qiu H, Ding K. 2011. Progress in function and mechanism study of heparan sulfate proteoglycan. Sci China. 23:648–661.

- Shafik A. 1984. Role of hemorrhoids in the pathogenesis of recurrent bacteriuria with a new approach for treatment. Eur Urol. 11:392–396.

- Song D, Shi B, Xue H, Li Y, Yu B, Xu Z, Liu F, Li J. 2006. Green fluorescent protein labeling Escherichia coli TG1 confirms intestinal bacterial translocation in a rat model of chemotherapy. Curr Microbiol. 52:69–73.

- Sun J. 2015. Clinical observation of 60 cases of Kangfuxin combined with San Qi in treatment of ulcerative colitis. Chin J Mod Drug Appl. 9:116.

- Van der Hulst RR, Von Meyenfeldt MF, Deutz NEP, Soeters PB, Brummer RJM, von Kreel BK, Arends JW. 1993. Glutamine and the preservation of gut integrity. Lancet. 341:1363–1365.

- Xu CT, Meng SY, Pan BR. 2004. Drug therapy for ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 10:2311–2317.

- Yan FX, Fang CS. 1991. Kang Fu Xin (KFX) in humoral immunity pharmacology characteristics of Chinese medicine. J Dali Med College. 13:79.

- Yao L. 1994. Study on the chemical composition of Chinese medicine cockroach Ι preliminary analysis of amino acid composition. Tianjin Pharmacy. 3:26–28.

- Zhen Z, Chen WW, Chen NW. 2008. Study on the mechanisms of Kangfuxin solution in the treatment of acute experimental colitis in rats. Chin J Gastroenterol. 1:31–34.