Abstract

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are major obstructive airway diseases that involve underlying airway inflammation. The most widely used pharmacotherapies for asthma and COPD are inhaled agents that have been shown to be effective and safe in these patients. However, despite the availability of effective pharmacologic treatment and comprehensive treatment guidelines, the prevalence of inadequately controlled asthma and COPD is high. A main reason for this is poor adherence. Adherence is a big problem for all chronic diseases, but in asthma and COPD patients there are some additional difficulties because of poor inhalation technique and inhaler choice. Easier-to-use devices and educational strategies on proper inhaler use from health caregivers can improve inhaler technique. The type of device used and the concordance between patient and physician in the choice of inhaler can also improve adherence and are as important as the drug. Adherence to inhaled therapy is absolutely necessary for optimizing patient control. If disease control is not adequate despite good adherence, switching to a more appropriate inhaled therapy is recommended. By contrast, uninformed switching or switching to less user-friendly inhaler may impact disease control negatively. This critical review of the available literature is aimed to provide a guidance protocol on when a switch may be recommended in individual patients.

Introduction

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are major chronic obstructive airway diseases that involve underlying airway inflammation, even if they substantially differ in pathophysiology and clinical features (Citation1, Citation2). Both asthma and COPD represent a major burden to society, with an estimated 300 million patients worldwide affected by asthma and roughly 3–13% of the general population diagnosed with COPD (Citation3, Citation4).

Most COPD and asthma patients require long-term maintenance treatment with pharmaceutical agents and inhalation is the preferable way to deliver these drugs (Citation1, Citation2). The major classes of inhaled drugs used to treat asthma and COPD include inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), short- and long-acting β2-agonists (SABA/LABA) and short- and long acting anti-muscarinic agents (SAMA-LAMA). ICS act on various biochemical pathways to reduce the underlying inflammation while SABA/LABA and SAMA/LAMA act on the sympathetic and parasympathetic pathways, respectively, to improve bronchial muscle tone and reduce bronchoconstriction. ICS therapy is the standard of care in asthmatics (Citation1). It is usually administered either alone or, for patients whose asthma is not sufficiently controlled with ICS alone, in combination with a LABA, often in a single inhaler (Citation1). SABAs are used as rescue therapy in intermittent or persistent uncontrolled asthma (Citation1). SABAs, LABAs and LAMAs are commonly used bronchodilators in symptomatic COPD patients (Citation2). Inhaled bronchodilators and ICS are also the most commonly used drugs for the maintenance treatment of COPD, as they reduce COPD symptoms, frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improve health status and exercise tolerance (Citation2).

Despite the availability of effective pharmacological treatments and comprehensive treatment guidelines, the prevalence of inadequately controlled asthma and COPD is high, and has only partially improved over the last few years (Citation1, Citation2, Citation5). Several studies have shown that 50–59% of patients with asthma are still not well controlled (Citation6–10). A main reason for uncontrolled asthma is poor adherence to the prescribed treatment (Citation11–14).

COPD is associated with partially reversible airflow obstruction and is often characterized by exertional dyspnea and acute exacerbations (Citation2). Currently available treatments are effective in reducing these problems (Citation2); however, the incidence of these symptoms remains high in COPD patients (Citation15, Citation16). As in patients with asthma, non-adherence was directly associated with worsened quality of life (Citation17, Citation18) and prognosis (Citation19).

The purpose of this review is to evaluate the issues involved in maintaining control of asthma and COPD, predominantly related to adherence to prescribed inhaled medications, and the potential benefits and risks of switching devices.

Definition and significance of adherence in chronic diseases with particular reference to asthma and COPD

Adherence is defined as the degree to which patients’ behavior coincides with the recommendations of health caregivers (HCGs) (Citation20). The World Health Organization has distinguished five potential factors that influence non-adherence: the patient, the disease, the treatment, the socioeconomic status and the healthcare system (Table ) (Citation20). Adherence to medications is a major problem for treatment of all chronic diseases.

Table 1. Description of the five potential domains related to non-adherence, as described by the World Health Organization (Citation20)

It averages 50% in developed countries and even less in developing areas (Citation20). In general, adherence to a regular long-term maintenance pharmacological treatment progressively decreases after the first prescription over time, as shown in Figure A (Citation20–22). It may be expected that it is impossible to achieve disease control without proper adherence to adequately prescribed medications. Of all medication-related hospital admissions in the United States, 33 to 69% are estimated to be due to poor medication adherence, with a resultant cost of approximately ∃100 billion a year (Citation23). Conversely, increased adherence to appropriate therapy has been associated with improved outcomes (Citation24) and reduced costs (Citation25).

Figure 1. Adherence to prescribed therapy in generic chronic diseases (A) and in chronic respiratory diseases (B), both in studies in a real-world setting. Notably, in inhaled therapy, device misuse is a major additional cause of non-adherence in real life (Citation14, Citation20, Citation21, Citation22, Citation28–31).

Chronic pulmonary diseases are associated with one of the lowest levels of adherence, ranking 15th out of 17 disease conditions (Citation26). Notably, this evaluation is possibly optimistic, as it does not include the challenge related to proper inhaler technique. To this aim it is important to underline the difference between intentional and non-intentional non-adherence to medications. Intentional non-adherence occurs when the patient decides either not to take the drug, or to take it only from time to time (erratic non-adherence), or with a different dose than prescribed (Citation27). Although more information is needed about this topic, intentional non-adherence to inhaled therapy in asthma and COPD patients does not seem to be substantially different from the rate of non-adherence in other chronic diseases and modalities of drug administration. Unintentional non-adherence occurs when a patient involuntarily either does not follow medical prescriptions or makes mistakes (Citation27).

Poor inhaler technique is a type of unintentional non-adherence (Citation27). Inhaler misuse is common in the real-world setting with both pressurized metered dose inhalers (pMDIs) and dry powder inhalers (DPIs), and it is associated with poor asthma and COPD control (Citation28).The addition of inhaler misuse largely decreases adherence rates, getting as low as 30%, in asthma and COPD patients, as displayed in Figure B (Citation14, Citation28–Citation31). Therefore, it is not surprising that in patients with asthma or COPD, non-adherence has been associated with increased mortality (Citation12, Citation13, Citation19), more hospitalizations (Citation14), higher healthcare costs (Citation14, Citation32, Citation33) and poor outcomes (Citation34, Citation35). Importantly, the problem of inhaler misuse is poorly perceived by patients (Citation36) and physicians (Citation37).

Do adherence rates differ between patients with asthma/COPD and other chronic respiratory diseases?

Another interesting question is the comparison in adherence rates between asthma/COPD and other chronic respiratory diseases. The issue is not easy to evaluate as the clinical evolution and the therapeutic approach between these diseases are very different. Some non-obstructive respiratory diseases, such as interstitial pneumonia and lung cancer, usually have a more rapid evolution than asthma and COPD. Treatment of lung cancer includes either surgery, or, alternatively or concomitantly, directly observed intermittent radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Cancer is reported to have better adherence rates than other chronic pulmonary diseases (Citation26). In contrast, in most COPD patients symptoms have a very slow and progressive onset and are mostly related to tobacco smoking, sometimes minimizing the value of inhaled therapy (Citation17). In asthma, both symptoms and airflow limitation vary over time and in intensity, enforcing the perception of its “sporadic” nature that can influence patients to stop maintenance therapy (Citation38).

Indeed, this finding is one of the reasons explaining the successful approach of using combination therapies (budesonide/formoterol or beclomethasone dipropionate [BDP]/formoterol) for both maintenance and rescue therapy in asthma (Citation1). Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, another common respiratory disorder, is treated effectively with the regular use of continuous positive airway pressure therapy while sleeping; no pharmacological treatments are approved for this condition. As such, pulmonary disease (excluding inhaler misuse) has slightly better adherence rates than sleep disturbances (Citation26). It appears the management of cystic fibrosis management has more similarities with asthma and COPD. Cystic fibrosis includes long-term pharmacological maintenance treatment with therapeutic aerosols, often time-consuming and without any immediate clinical effect. It is well-known that adherence rates are very low in cystic fibrotic patients and worse adherence

Is it possible to successfully measure adherence in chronic disease?

Despite the awareness that non-adherence is a major problem for effective asthma as well as COPD management, literature on this topic is limited. Many methodological problems, sometimes typical of inhaled treatment, complicate the full evaluation of this issue. First, there is no universal agreement on how to define adherence. In the TORCH study, the threshold for good adherence was defined as >80% use of overall prescribed medications (Citation19). However, this value is arbitrary and some authors have used other threshold values (Citation19, Citation40–Citation45). Second, a range of methods have been proposed to monitor adherence (Citation27). Biochemical measurements, electronic monitor devices, medical/pharmacy records, residual doses monitoring, clinical judgment, and patient self-reporting can all be used as adherence indicators. Each of these methods have advantages and disadvantages (in terms of cost, time spent, practicality, validity, and reliability), and none of them is an accepted gold standard, at least in clinical practice (Citation27).

In fact, even if advances in technology have permitted improvements in adherence control with easy, cheap and less cumbersome electronic systems directly applied to inhaler devices, their usefulness in improving adherence and asthma and COPD control still has to be demonstrated. Third, inhaler misuse, another issue that can undermine adherence in asthma and COPD, is not easy to evaluate objectively and it is time consuming in clinical practice. For this reason, inhaler misuse should be assessed in real life simply sharing standardized step-by-step instruction checklists (usually reported in the product information leaflets) with the patient, testing their ability in using the inhaler and training them, if necessary. A comprehensive list including all inhalers in the market, edited by scientific societies, could be desirable, but unfortunately is not realistic, due to the variability in usage of devices. Moreover, the trained HCG cannot directly and objectively evaluate some important issues (e.g., the inspiratory peak flow and the flow acceleration through the device).

Methods of improving medication adherence and educational strategies for reducing inhaler misuse

The issue of medication non-adherence is not only hard to evaluate but also difficult to address due to its multi-factorial nature (Citation46). Importantly, some studies have shown that significant improvement in adherence can be achieved (Citation47, Citation48). These studies demonstrate that adherence is a modifiable behavior and a proper strategy is important to improve it. Possibly this strategy does not differ between subjects with asthma and COPD, and other chronic diseases (Citation49).

As inhaler misuse is an additional issue contributing to poor adherence in asthma and COPD patients, methods able to improve inhaler technique are very important. Effectively, GINA and GOLD guidelines stress the importance of proper inhaler use (Citation1, Citation2). Unfortunately, in the real-world setting, the role of inhaler technique is often neglected by patients (Citation36), and physicians (Citation37), with improper inhaler technique ranging from 30% to 90% (Citation50, Citation51).The most important modifiable factors associated with inhaler misuse are training on proper device technique by HCGs and making inhalers easier to use (Citation52, Citation53).

It has been shown that extensive (>5 minutes) face-to-face practical instruction of proper inhaler use at prescription, and regular checks at follow-up visits, are associated with improved inhaler technique, reduced use of unscheduled health care resources and quality of life (Citation54). Furthermore, instruction on inhalation technique has also been associated with improved treatment adherence in patients with COPD (Citation55) and asthma (Citation56). Inhaler education is rewarding, but time-consuming for busy physicians. However, not only physicians, but other HCGs, such as nurses, physiotherapists, respiratory technicians and pharmacists (Citation57–Citation67) can successfully contribute to give instruction on improved inhaler technique.

Potential role of novel inhaler technology in reducing inhaler misuse

It is well-known that, despite proper and repeated instruction, some patients do not always succeed in using their device correctly (Citation68–70). A proper evaluation of the patient by the physician is crucial for correct selection of inhaler, as several factors can represent barriers to effective inhaler use. Comorbidities and physical issues (such as tremors, poor hand-breath coordination, poor dexterity, arthritis in the hands, poor eyesight, hearing impairment, etc.), as well as low literacy, may often necessitate a specific device and training approach (Citation71–73). Although it is generally accepted that different devices are clinically equivalent with regard to safety and efficacy when they are used to deliver the same drug (Citation74), each device has its own properties and usability.

The type of device and the drug formulation used to treat asthma and COPD can influence inhaler misuse. The use of devices that allow the inhalation of extrafine particles (such as extrafine BDP, ciclesonide, extrafine pMDIs and DPI BDP/formoterol combinations and aerosols delivered by the soft mist inhalers) have shown a much greater lung drug delivery – and consequently a greater efficiency – than traditional aerosols (Citation75–Citation80). Furthermore, extrafine aerosols have an improved particle size distribution with greater peripheral lung distribution and homogeneity of drug delivery (Citation76, Citation79, Citation81–84). In view of the recognition of the increasing role of small airways in asthma and COPD (Citation75, Citation78), it is not unexpected that extrafine aerosols have a greater impact than traditional aerosols on asthma and COPD outcomes (Citation6, Citation77, Citation79, Citation81, Citation85–89).

Although technology advances are not expected to solve all issues of treatment adherence, they have the potential to improve inhaler handling with both pMDIs and DPIs. Extrafine pMDIs are formulated as solutions rather than suspensions, thus eliminating one of the risks associated with variable and reduced lung delivery of the drug (Citation90). Furthermore, some newer better performing pMDIs have a softer, warmer aerosol plume (Citation91, Citation92), which can reduce the risk of cold-freon effect and the need for perfect hand-breath coordination and slow inhalation (Citation93, Citation94). In fact, with extrafine drug formulations there is not only a correlation between small particle size and better lung distribution, but also less dependence between inhalation technique and lung deposition (Citation80).

Therefore, with the increased use of newer pMDIs, it is not surprising that the real-world rates of inhaler misuse with pMDIs have been reported to decrease (Citation95). Of course, technology advances are also important for DPIs. Being breath actuated, DPIs do not require hand-breath coordination, a common mistake when using MDIs. However, DPI use is associated with other difficulties of poor handling (Citation28, Citation36). A major concern using DPIs is that they rely on the patients’ inspiratory flow for effective lung delivery of the drug. Some patients cannot achieve the minimally effective peak inhalation flow (PIF) to properly disperse drug powder (Citation96). As each DPI has a peculiar in-built resistance, this was thought to occur mainly using DPIs with high inhaler resistance (Citation97). In contrast, traditionally it was believed that DPIs with greater inhaler resistance could assure higher lung drug deposition. However, recent studies do not necessarily confirm this finding (Citation98). Some newer DPIs offer high lung drug delivery and produce an extrafine aerosol without significantly increasing the intrinsic inhaler resistance (Citation99).

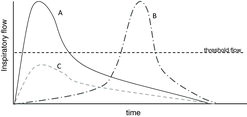

Moreover, not only is the PIF important for proper aerosol dispersion of DPIs formulation, but the flow acceleration at the start of inhalation is as important (Citation100). Possibly some patients achieve the proper PIF with a certain DPI, but late during inhalation. In these conditions drug delivery is poor with traditional DPIs (Figure ) (Citation100). In order to overcome this variety of misuse related to a relatively slow flow slope, some of the newest marketed DPI devices include a Breath Actuated Mechanism (BAM), which ensures that the dose is released only when the patient achieves the proper inspiratory flow through the inhaler able to disaggregate the powder successfully (Citation101–Citation103).

Figure 2. Three typical flow profile curves from patients inhaling through a DPI device. Using the classical DPIs, the only effective one is the A profile, which imposes an elevated acceleration at the start of inhalation. The B profile achieves the threshold flow too late, negatively conditioning the quality of particle size. The C profile is inadequate because it does not reach the threshold flow to accurately deliver the dose.

These newer devices, thanks to the add-on BAM, can deliver the dose even with a lower starting flow, as long as the critical flow is then reached, so that patients will receive the correct dose independently from the flow profile. In this way, BAM operates as a “all or nothing” system, ensuring constancy and repeatability of the emitted dose (Citation99). In other words, the BAM may be considered an add-on pro-active feedback mechanism that confirms correct administration of the dose and not simply its loading. Other feedback systems are linked to taste (e.g., an excipient with a distinctive taste), to sight (e.g., a dose counter that indicates the dose delivery only if the dose is correctly released and inhaled, in other words an “inhalation counter” not a “dose counter”) and to hearing (e.g., an audible “click” when the dose is released).

Another critical issue seems to be the number of steps needed to correctly prepare the dose in DPIs. An observational study performed in patients with experience with inhaled drugs revealed an increased number of errors by users of more complex inhaler systems, with consequent increased risk of hospitalization, emergency room visits, use of antibiotic and systemic corticosteroid (Citation104). Furthermore, there is a correlation between fewer steps required for use, better inhalation technique and satisfaction (Citation105). Of course, further studies are required to confirm the advantages offered by this new generation devices; advantages of newer DPIs are summarized in

Table 2. Main characteristics differentiating classical and newer dry-powder inhalers (DPIs) (Citation84, Citation99, Citation100)

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have recognized the key role of delivery devices for aerosol therapy in respiratory medicine. They emphasize that, for approval of a new inhaled drug delivery device, the applicant has to provide evidence for the safety, efficacy and quality of the delivery system. This evidence has to be documented according to regulatory requirements and the process for approval is similar to that of the drug approval process. This process may occur commonly, as the patent of some inhaled drugs often expires earlier than that of devices and some manufacturers are recovering old devices or producing new inhalers. Known drugs are often developed by putting them into new types of inhaler devices, thus creating new drug delivery systems. In this case, the EMA allows the approval of a generic version of an inhaler product based on in-vitro assessments (in the case of in-vitro equivalence) or lung deposition tests, complemented with pharmacodynamic and phase III clinical studies (when in-vitro comparability is not demonstrated) (Citation106, Citation107).

Managing device switching to improve adherence and achieve asthma and COPD control

There are several reasons for switching a patient from one inhaler device to another. Possibly the most common reason is when the patient informs the physician that the prescribed therapeutic choice is not working. This switch requires a careful evaluation of the case, including non-adherence in its larger significance (Citation108). Apart from the choice of the drug, the International Primary Care Respiratory Group states that before switching, the following questions should be addressed:

Is the patient complying with their prescribed medication?

Has the most appropriate inhaler device been chosen for the individual patient?

Is the patient using the inhalation technique recommended by the manufacturer?

Has smoking cessation been adequately encouraged if applicable?

Has management of concurrent comorbidities such as rhinitis been maximized?

Only patients who answer ‘yes’ to all of the above questions, but are still inadequately controlled, should be considered for switching to an alternative device (Citation109). When all these conditions are satisfied, switching may be useful and may improve disease control, satisfaction and adherence (Citation110).

The selection of the most appropriate device for a switch is as critical as the initial selection of inhaled drug. The careful choice of the most appropriate inhaler device can certainly improve clinical outcomes (Citation109, Citation111). The patient should be involved in the choice of the device, as it seems logical to suppose that the patient's preference and satisfaction will influence adherence and, in turn, improve disease control (Citation112–Citation114). Overall, simplifying the regimen schedule by including the use of a single inhaler with different drug combinations, or only a type of inhaler, or the addition of bronchodilators with fast onset of action may be beneficial (Citation115–Citation118). Introducing easier-to-use devices with pro-active feed-back mechanisms able to teach the patient when an effective dosing has been delivered successfully is also useful.

Switching inhalers might be required for economic reasons. It is possible that, due to budgetary constraints, a well-controlled asthma or COPD patient may be switched to an apparently cheaper alternative device; the typical example is switching from a branded to a generic medication. However, it has to be taken into account that a proper change of inhaler has to be accompanied by a clinical evaluation and patient consultation in order to explain the reason for switching, to give new and extensive instructions in the use of the new inhaler, and to confirm that the skills for proper inhaler use have been acquired.

Alternatively, uninformed switching may negatively affect disease control, leading to patient discontent and worsening adherence (Citation119). A large survey in patients with asthma and COPD showed that 60–85% of patients thought that switching devices could be feasible only if they were advised by the physician; however, 86% of these patients wished to know exactly how the new prescribed inhaler worked (Citation120). Furthermore, in a UK study where ICS devices were switched without consultation, patients experienced less successful treatment compared with a matched group of patients using the same device, but who were not switched (Citation121).

HCGs also think that a drug/inhaler system is not easily interchangeable (Citation122). In a survey of 254 pharmacists throughout Europe, only 6% considered inhalers to be switchable, with a high percentage of those taking part in the survey showing concern about interchangeable inhaler use. Patient confusion was the main concern, expressed by 77% of respondents (Citation123). In another survey conducted in Australia, Canada, France, Germany and United Kingdom, over 90% of the 726 physicians interviewed thought that changing inhalers would have a negative impact on patient compliance, device handling, and willingness to use the inhaler if the patient was not involved in the choice. Only 9% of physicians thought that inhalers were substitutable, with any cost benefits likely to be outweighed by the need for additional consultations and prescriptions (Citation124).

These data clearly show that an inhaler switch may be successfully performed only in accordance between HCGs and patients.

Conclusions

Many asthma and COPD patients remain uncontrolled despite the availability of effective treatments. Much of this lack of control is due to poor adherence to inhaled therapy. Adherence is a big problem for all chronic diseases, but in chronic obstructive airways diseases it has some additional difficulties related to poor inhaler technique and inhaler choice. Key points for optimizing adherence to inhaler therapy and improving asthma and COPD control can be crystallized in the concepts that the inhaler device is as important as the active ingredient, the choice of the device has to be carefully evaluated by the prescribing physician in agreement with the patient, and extensive and repeated education on proper inhaler use is absolutely necessary as well as technology advancements have to make devices easier to use.

When disease control is suboptimal, a switch to a more appropriate inhaled therapy may be appropriate. Conversely, uninformed switching or changing to a less user-friendly inhaler may negatively affect disease control. It is important to highlight the right of the patient for high-quality therapy and to avoid apparent reduction of costs, since the loss of disease control or its worsening may lead to waste due to unused prescriptions, and extra expense due to additional visits to the physician. A non-adherent patient or a poorly used device creates unnecessary additional costs for the health system.

Declaration of Interest Statement

A. S. Melani has served as an advisory board member, has been reimbursed for speaker honoraria and has received fees as a consultant for Chiesi, Menarini, Novartis, Mundipharma, Almirall, GSK and Artsana. D. Paleari is employed by Chiesi Farmaceutici SpA.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing assistance was provided by Mary Hines and Simone Boniface of Springer Healthcare Communications, funded by Chiesi Farmaceutici SpA.

References

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2014 [cited 2014 Nov 26]; Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/local/uploads/files/GINA_Report_2014_Aug12.pdf.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2014 [cited 2014 Nov 26]; Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org/local/uploads/files/GINA_Report_2014_Aug12.pdf3.

- Cazzola M, Segreti A, Bettoncelli G, Calzetta L, Cricelli C, Pasqua F, et al.Change in asthma and COPD prescribing by Italian general practitioners between 2006 and 2008. Prim Care Respir J 2011; 20(3):291–298.

- Ciapponi A, Alison L, Agustina M, Demian G, Silvana C, Edgardo S. The epidemiology and burden of COPD in Latin America and the Caribbean: systematic review and meta-analysis. COPD 2014; 11(3):339–350.

- Holgate S, Bisgaard H, Bjermer L, Haahtela T, Haughney J, Horne R, et al.The Brussels Declaration: the need for change in asthma management. Eur Respir J 2008; 32(6):1433–1442.

- Allegra L, Cremonesi G, Girbino G, Ingrassia E, Marsico S, Nicolini G, et al.Real-life prospective study on asthma control in Italy: cross-sectional phase results. Respir Med 2012; 106(2):205–214.

- Chapman KR, Boulet LP, Rea RM, Franssen E. Suboptimal asthma control: prevalence, detection and consequences in general practice. Eur Respir J 2008; 31(2):320–325.

- Demoly P, Paggiaro P, Plaza V, Bolge SC, Kannan H, Sohier B, et al.Prevalence of asthma control among adults in France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK. Eur Respir Rev 2009; 18(112):105–112.

- Partridge MR, van der Molen T, Myrseth SE, Busse WW. Attitudes and actions of asthma patients on regular maintenance therapy: the INSPIRE study. BMC Pulm Med 2006; 6:13.

- Peters SP, Jones CA, Haselkorn T, Mink DR, Valacer DJ, Weiss ST. Real-world Evaluation of Asthma Control and Treatment (REACT): findings from a national Web-based survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119(6):1454–1461.

- Cutler DM, Everett W. Thinking outside the pillbox–medication adherence as a priority for health care reform. N Engl J Med 2010; 362(17):1553–1555.

- Birkhead G, Attaway NJ, Strunk RC, Townsend MC, Teutsch S. Investigation of a cluster of deaths of adolescents from asthma: evidence implicating inadequate treatment and poor patient adherence with medications. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1989; 84(4 Pt 1):484–491.

- Harrison B, Stephenson P, Mohan G, Nasser S. An ongoing Confidential Enquiry into asthma deaths in the Eastern Region of the UK, 2001-2003. Prim Care Respir J 2005; 14(6):303–313.

- Williams LK, Pladevall M, Xi H, Peterson EL, Joseph C, Lafata JE, et al.Relationship between adherence to inhaled corticosteroids and poor outcomes among adults with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2004; 114(6):1288–1293.

- Barnes N, Calverley PM, Kaplan A, Rabe KF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and exacerbations: patient insights from the global Hidden Depths of COPD survey. BMC Pulm Med 2013; 13:54.

- Paladini L, Hodder R, Cecchini I, Bellia V, Incalzi RA. The MRC dyspnoea scale by telephone interview to monitor health status in elderly COPD patients. Respir Med 2010; 104(7):1027–1034.

- Ágh T, Inotai A, Meszaros A. Factors associated with medication adherence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration 2011; 82(4):328–334.

- Bosley CM, Parry DT, Cochrane GM. Patient compliance with inhaled medication: does combining beta-agonists with corticosteroids improve compliance? Eur Respir J 1994; 7(3):504–509.

- Vestbo J, Anderson JA, Calverley PM, Celli B, Ferguson GT, Jenkins C, et al.Adherence to inhaled therapy, mortality and hospital admission in COPD. Thorax 2009; 64(11):939–943.

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: Evidence for action. Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Cheetham TC, Niu F, Green K, Scott RD, Derose SF, Vansomphone SS, et al.Primary nonadherence to statin medications in a managed care organization. J Manag Care Pharm 2013; 19(5):367–373.

- Jackevicius CA, Mamdani M, Tu JV. Adherence with statin therapy in elderly patients with and without acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2002; 288(4):462–467.

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005; 353(5):487–497.

- Simpson SH, Eurich DT, Majumdar SR, Padwal RS, Tsuyuki RT, Varney J, et al.A meta-analysis of the association between adherence to drug therapy and mortality. Br Med J 2006; 333(7557):15.

- Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, Epstein RS. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care 2005; 43(6):521–530.

- DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients' adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care 2004; 42(3):200–209.

- Rau JL. Determinants of patient adherence to an aerosol regimen. Respir Care 2005; 50(10):1346–1356; discussion 1357–1349.

- Melani AS, Bonavia M, Cilenti V, Cinti C, Lodi M, Martucci P, et al.Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med 2011; 105(6):930–938.

- Molimard M, Raherison C, Lignot S, Depont F, Abouelfath A, Moore N. Assessment of handling of inhaler devices in real life: an observational study in 3811 patients in primary care. J Aerosol Med 2003 Fall; 16(3):249–254.

- Rand CS, Nides M, Cowles MK, Wise RA, Connett J. Long-term metered-dose inhaler adherence in a clinical trial. The Lung Health Study Research Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995; 152(2):580–588.

- Williams LK, Joseph CL, Peterson EL, Wells K, Wang M, Chowdhry VK, et al.Patients with asthma who do not fill their inhaled corticosteroids: a study of primary nonadherence. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 120(5):1153–1159.

- Gamble J, Stevenson M, McClean E, Heaney LG. The prevalence of nonadherence in difficult asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180(9):817–822.

- Wilson SR, Strub P, Buist AS, Knowles SB, Lavori PW, Lapidus J, et al.Shared treatment decision making improves adherence and outcomes in poorly controlled asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2010; 181(6):566–577.

- Bauman LJ, Wright E, Leickly FE, Crain E, Kruszon-Moran D, Wade SL, et al.Relationship of adherence to pediatric asthma morbidity among inner-city children. Pediatrics 2002; 110(1 Pt 1):e6.

- Clatworthy J, Price D, Ryan D, Haughney J, Horne R. The value of self-report assessment of adherence, rhinitis and smoking in relation to asthma control. Prim Care Respir J 2009; 18(4):300–305.

- Melani AS, Zanchetta D, Barbato N, Sestini P, Cinti C, Canessa PA, et al.Inhalation technique and variables associated with misuse of conventional metered-dose inhalers and newer dry powder inhalers in experienced adults. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2004; 93(5):439–446.

- Papi A, Haughney J, Virchow JC, Roche N, Palkonen S, Price D. Inhaler devices for asthma: a call for action in a neglected field. Eur Respir J 2011; 37(5):982–985.

- Halm EA, Mora P, Leventhal H. No symptoms, no asthma: the acute episodic disease belief is associated with poor self-management among inner-city adults with persistent asthma. Chest 2006; 129(3):573–580.

- Quittner AL, Zhang J, Marynchenko M, Chopra PA, Signorovitch J, Yushkina Y, et al.Pulmonary medication adherence and health-care use in cystic fibrosis. Chest 2014; 146(1):142–151.

- Cecere LM, Slatore CG, Uman JE, Evans LE, Udris EM, Bryson CL, et al.Adherence to long-acting inhaled therapies among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). COPD 2012; 9(3):251–258.

- Barnestein-Fonseca P, Leiva-Fernandez J, Vidal-Espana F, Garcia-Ruiz A, Prados-Torres D, Leiva-Fernandez F. Efficacy and safety of a multifactor intervention to improve therapeutic adherence in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): protocol for the ICEPOC study. Trials 2011; 12:40.

- Klok T, Kaptein AA, Duiverman EJ, Brand PL. It's the adherence, stupid (that determines asthma control in preschool children)! Eur Respir J 2014; 43(3):783–791.

- Neugaard BI, Priest JL, Burch SP, Cantrell CR, Foulis PR. Quality of care for veterans with chronic diseases: performance on quality indicators, medication use and adherence, and health care utilization. Popul Health Manag 2011; 14(2):99–106.

- Souza-Machado A, Santos PM, Cruz AA. Adherence to treatment in severe asthma: predicting factors in a program for asthma control in Brazil. World Allergy Organ J 2010; 3(3):48–52.

- Van Steenis M, Driesenaar J, Bensing J, Van Hulten R, Souverein P, Van Dijk L, et al.Relationship between medication beliefs, self-reported and refill adherence, and symptoms in patients with asthma using inhaled corticosteroids. Patient Prefer Adherence 2014; 8:83–91.

- Nieuwlaat R, Wilczynski N, Navarro T, Hobson N, Jeffery R, Keepanasseril A, et al.Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 11:CD000011.

- Horne R, Chapman SC, Parham R, Freemantle N, Forbes A, Cooper V. Understanding patients' adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: a meta-analytic review of the Necessity-Concerns Framework. PLoS One 2013; 8(12):e80633.

- Demonceau J, Ruppar T, Kristanto P, Hughes DA, Fargher E, Kardas P, et al.Identification and assessment of adherence-enhancing interventions in studies assessing medication adherence through electronically compiled drug dosing histories: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Drugs 2013; 73(6):545–562.

- Horne R. Adherence to asthma medication: a question of ability? Prim Care Respir J 2011; 20(2):118–119.

- Lavorini F, Magnan A, Dubus JC, Voshaar T, Corbetta L, Broeders M, et al.Effect of incorrect use of dry powder inhalers on management of patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med 2008; 102(4):593–604.

- McFadden ER, Jr. Improper patient techniques with metered dose inhalers: clinical consequences and solutions to misuse. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995; 96(2):278–283.

- Rootmensen GN, van Keimpema AR, Jansen HM, de Haan RJ. Predictors of incorrect inhalation technique in patients with asthma or COPD: a study using a validated videotaped scoring method. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2010; 23(5):323–328.

- Sestini P, Cappiello V, Aliani M, Martucci P, Sena A, Vaghi A, et al.Prescription bias and factors associated with improper use of inhalers. J Aerosol Med 2006; 19(2):127–136.

- Goris S, Tasci S, Elmali F. The effects of training on inhaler technique and quality of life in patients with COPD. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2013; 26(6):336–344.

- Takemura M, Mitsui K, Itotani R, Ishitoko M, Suzuki S, Matsumoto M, et al.Relationships between repeated instruction on inhalation therapy, medication adherence, and health status in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2011; 6:97–104.

- Takemura M, Kobayashi M, Kimura K, Mitsui K, Masui H, Koyama M, et al.Repeated instruction on inhalation technique improves adherence to the therapeutic regimen in asthma. J Asthma 2010; 47(2):202–208.

- Takemura M, Mitsui K, Ido M, Matsumoto M, Koyama M, Inoue D, et al.Impact of a network system for providing proper inhalation technique by community pharmacists. J Asthma 2012; 49(5):535–541.

- Mehuys E, Van Bortel L, De Bolle L, Van Tongelen I, Annemans L, Remon JP, et al.Effectiveness of pharmacist intervention for asthma control improvement. Eur Respir J 2008; 31(4):790–799.

- Armour C, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Brillant M, Burton D, Emmerton L, Krass I, et al.Pharmacy Asthma Care Program (PACP) improves outcomes for patients in the community. Thorax 2007; 62(6):496–502.

- Barbanel D, Eldridge S, Griffiths C. Can a self-management programme delivered by a community pharmacist improve asthma control? A randomised trial. Thorax 2003; 58(10):851–854.

- Basheti IA, Reddel HK, Armour CL, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ. Improved asthma outcomes with a simple inhaler technique intervention by community pharmacists. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007; 119(6):1537–1538.

- Cordina M, McElnay JC, Hughes CM. Assessment of a community pharmacy-based program for patients with asthma. Pharmacotherapy 2001; 21(10):1196–1203.

- Kritikos V, Armour CL, Bosnic-Anticevich SZ. Interactive small-group asthma education in the community pharmacy setting: A pilot study. J Asthma 2007; 44(1):57–64.

- McLean W, Gillis J, Waller R. The BC Community Pharmacy Asthma Study: A study of clinical, economic and holistic outcomes influenced by an asthma care protocol provided by specially trained community pharmacists in British Columbia. Can Respir J 2003; 10(4):195–202.

- Self TH, Brooks JB, Lieberman P, Ryan MR. The value of demonstration and role of the pharmacist in teaching the correct use of pressurized bronchodilators. Can Med Assoc J 1983; 128(2):129–131.

- Takemura M, Mitsui K, Ido M, Matsumoto M, Koyama M, Inoue D, et al.Effect of a network system for providing proper inhalation technique by community pharmacists on clinical outcomes in COPD patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2013; 8:239–244.

- Wang KY, Chian CF, Lai HR, Tarn YH, Wu CP. Clinical pharmacist counseling improves outcomes for Taiwanese asthma patients. Pharm World Sci 2010; 32(6):721–729.

- Wieshammer S, Dreyhaupt J. Dry powder inhalers: Which factors determine the frequency of handling errors? Respiration 2008; 75(1):18–25.

- Hardwell A, Barber V, Hargadon T, McKnight E, Holmes J, Levy ML. Technique training does not improve the ability of most patients to use pressurised metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs). Prim Care Respir J 2011; 20(1):92–96.

- Levy ML, Hardwell A, McKnight E, Holmes J. Asthma patients' inability to use a pressurised metered-dose inhaler (pMDI) correctly correlates with poor asthma control as defined by the global initiative for asthma (GINA) strategy: a retrospective analysis. Prim Care Respir J 2013; 22(4):406–411.

- Wolstenholme RJ, Shettar SP, Taher F, Hatton B. Use of Haleraid in rheumatoid arthritis with obstructive lung disease. Br J Rheumatol 1986; 25(3):318.

- Press VG, Arora VM, Shah LM, Lewis SL, Ivy K, Charbeneau J, et al.Misuse of respiratory inhalers in hospitalized patients with asthma or COPD. J Gen Intern Med 2011; 26(6):635–642.

- O'Conor R, Wolf MS, Smith SG, Martynenko M, Vicencio DP, Sano M, et al.Health literacy, cognitive function, proper use and adherence to inhaled asthma controller medications among older adults with asthma. Chest 2014 Oct 2 [Epub ahead of print].

- Dolovich MB, Ahrens RC, Hess DR, Anderson P, Dhand R, Rau JL, et al.Device selection and outcomes of aerosol therapy: Evidence-based guidelines: American College of Chest Physicians/American College of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology. Chest 2005; 127(1):335–371.

- Bjermer L. The role of small airway disease in asthma. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2014; 20(1):23–30.

- Brand P, Hederer B, Austen G, Dewberry H, Meyer T. Higher lung deposition with Respimat Soft Mist inhaler than HFA-MDI in COPD patients with poor technique. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2008; 3(4):763–770.

- Brusselle G, Peche R, Van den Brande P, Verhulst A, Hollanders W, Bruhwyler J. Real-life effectiveness of extrafine beclometasone dipropionate/formoterol in adults with persistent asthma according to smoking status. Respir Med 2012; 106(6):811–819.

- Hogg JC, McDonough JE, Suzuki M. Small airway obstruction in COPD: new insights based on micro-CT imaging and MRI imaging. Chest 2013; 143(5):1436–1443.

- Mariotti F, Francesco F, Acerbi D, Meyer T, Herpich C. Lung deposition of the extra fine dry powder fixed combination beclomethasone dipropionate plus formoterol fumarate via the NEXT DPI® in healthy subjects, asthmatic and COPD patients. Eur Respir J 2011; 38(Suppl 55):139s [abstract P830].

- Usmani OS, Biddiscombe MF, Barnes PJ. Regional lung deposition and bronchodilator response as a function of beta2-agonist particle size. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005; 172(12):1497–1504.

- De Backer W, Devolder A, Poli G, Acerbi D, Monno R, Herpich C, et al.Lung deposition of BDP/formoterol HFA pMDI in healthy volunteers, asthmatic, and COPD patients. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2010; 23(3):137–148.

- Leach CL, Bethke TD, Boudreau RJ, Hasselquist BE, Drollmann A, Davidson P, et al.Two-dimensional and three-dimensional imaging show ciclesonide has high lung deposition and peripheral distribution: a nonrandomized study in healthy volunteers. J Aerosol Med 2006; 19(2):117–126.

- Leach CL, Colice GL. A pilot study to assess lung deposition of HFA-beclomethasone and CFC-beclomethasone from a pressurized metered dose inhaler with and without add-on spacers and using varying breathhold times. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2010; 23(6):355–361.

- Scichilone N, Spatafora M, Battaglia S, Arrigo R, Benfante A, Bellia V. Lung penetration and patient adherence considerations in the management of asthma: role of extra-fine formulations. J Asthma Allergy 2013; 6:11–21.

- Muller V, Galffy G, Eszes N, Losonczy G, Bizzi A, Nicolini G, et al.Asthma control in patients receiving inhaled corticosteroid and long-acting beta2-agonist fixed combinations. A real-life study comparing dry powder inhalers and a pressurized metered dose inhaler extrafine formulation. BMC Pulm Med 2011; 11:40.

- Price D, Small I, Haughney J, Ryan D, Gruffydd-Jones K, Lavorini F, et al.Clinical and cost effectiveness of switching asthma patients from fluticasone-salmeterol to extra-fine particle beclometasone-formoterol: a retrospective matched observational study of real-world patients. Prim Care Respir J 2013; 22(4):439–448.

- Terzano C, Cremonesi G, Girbino G, Ingrassia E, Marsico S, Nicolini G, et al.1-year prospective real life monitoring of asthma control and quality of life in Italy. Respir Res 2012; 13:112.

- Colice G, Martin RJ, Israel E, Roche N, Barnes N, Burden A, et al.Asthma outcomes and costs of therapy with extrafine beclomethasone and fluticasone. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 132(1):45–54.

- Postma DS, O'Byrne PM, Pedersen S. Comparison of the effect of low-dose ciclesonide and fixed-dose fluticasone propionate and salmeterol combination on long-term asthma control. Chest 2011; 139(2):311–318.

- Thorsson L, Edsbacker S. Lung deposition of budesonide from a pressurized metered-dose inhaler attached to a spacer. Eur Respir J 1998; 12(6):1340–1345.

- Acerbi D, Brambilla G, Kottakis I. Advances in asthma and COPD management: delivering CFC-free inhaled therapy using Modulite technology. Pulm Pharmacol Ther 2007; 20(3):290–303.

- Buttini F, Miozzi M, Balducci AG, Royall PG, Brambilla G, Colombo P, et al.Differences in physical chemistry and dissolution rate of solid particle aerosols from solution pressurised inhalers. Int J Pharm 2014; 465(1–2):42–51.

- Leach CL, Davidson PJ, Hasselquist BE, Boudreau RJ. Influence of particle size and patient dosing technique on lung deposition of HFA-beclomethasone from a metered dose inhaler. J Aerosol Med 2005; 18(4):379–385.

- Nicolini G, Scichilone N, Bizzi A, Papi A, Fabbri LM. Beclomethasone/formoterol fixed combination for the management of asthma: patient considerations. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2008; 4(5):855–864.

- Zagà V, Mariano V, Vakeffliu Y, Ribolla R, Sini A, Coloretti I, et al.Is inhaler technique improving in Italy? [Italian] Uso scorretto degli inalatori per l'asma e la BPCO: In Italia sta cambiando qualcosa? Rassegna di Patologia dell'Apparato Respiratorio 2012; 27(4):211–218.

- Haughney J, Price D, Barnes NC, Virchow JC, Roche N, Chrystyn H. Choosing inhaler devices for people with asthma: current knowledge and outstanding research needs. Respir Med 2010; 104(9):1237–1245.

- Clark AR, Hollingworth AM. The relationship between powder inhaler resistance and peak inspiratory conditions in healthy volunteers–implications for in vitro testing. J Aerosol Med 1993; 6(2):99–110.

- Shur J, Lee S, Adams W, Lionberger R, Tibbatts J, Price R. Effect of device design on the in vitro performance and comparability for capsule-based dry powder inhalers. AAPS J 2012; 14(4):667–676.

- Corradi M, Chrystyn H, Cosio BG, Pirozynski M, Loukides S, Louis R, et al.NEXThaler, an innovative dry powder inhaler delivering an extrafine fixed combination of beclometasone and formoterol to treat large and small airways in asthma. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2014; 11(9):1497–1506.

- Everard ML, Devadason SG, Le Souef PN. Flow early in the inspiratory manoeuvre affects the aerosol particle size distribution from a Turbuhaler. Respir Med 1997; 91(10):624–628.

- Chiesi, European Medicines Committee. Fostair 100/6 inhalation solution: summary of product characteristics. [cited April 3 2014 ]; Available from: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/21006/SPC/

- Pasquali I, Brambilla G, Long EJ, Hargrave GK, H.K. V. A visualisation study for the aerosol generation in NEXThaler® [abstract]. Annual Meeting and Exposition of the American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists (AAPS); Chicago, USA, 2012.

- Scuri M, Alfieri V, Giorgio A, Pisi R, Ferrari F, Taverna M, et al.Measurement of the inhalation profile through a novel dry powder inhaler (Nexthaler®) in asthmatic patients using acoustic monitoring [abstract]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013; 187:A1931.

- Melani AS, Canessa P, Coloretti I, DeAngelis G, DeTullio R, Del Donno M, et al.Inhaler mishandling is very common in patients with chronic airflow obstruction and long-term home nebuliser use. Respir Med 2012; 106(5):668–676.

- Voshaar T, Spinola M, Linnane P, Campanini A, Lock D, Lafratta A, et al.Comparing usability of NEXThaler with other inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting beta-agonist fixed combination dry powder inhalers in asthma patients. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 2013.

- Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Note for guidance on the clinical development of medicinal products in the treatment of asthma (CPMP/EWP/2922/01). 2002 [cited 2013 29 January]; Available from: http://www.emea.europa.eu/pdfs/human/ewp/292201en.pdf.

- Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Concept paper on the need for revision of the CHMP note for guidance on the clinical development of medicinal products in the treatment of asthma (CPMP/EWP/2922/01). 2009 [cited 2013 29 January]; Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/10/WC500006234.pdf.

- Rubin BK. What does it mean when a patient says, "my asthma medication is not working"? Chest 2004; 126(3):972–981.

- Chrystyn H, Price D. Not all asthma inhalers are the same: factors to consider when prescribing an inhaler. Prim Care Respir J 2009; 18(4):243–249.

- Giraud V, Allaert FA. Improved asthma control with breath-actuated pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI): the SYSTER survey. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2009; 13(5):323–330.

- Virchow JC, Crompton GK, Dal Negro R, Pedersen S, Magnan A, Seidenberg J, et al.Importance of inhaler devices in the management of airway disease. Respir Med 2008; 102(1):10–19.

- Chrystyn H, Small M, Milligan G, Higgins V, Gil EG, Estruch J. Impact of patients' satisfaction with their inhalers on treatment compliance and health status in COPD. Respir Med 2014; 108(2):358–365.

- Dolovich L, Nair K, Sellors C, Lohfeld L, Lee A, Levine M. Do patients' expectations influence their use of medications? Qualitative study. Can Fam Physician 2008; 54(3):384–393.

- Makela MJ, Backer V, Hedegaard M, Larsson K. Adherence to inhaled therapies, health outcomes and costs in patients with asthma and COPD. Respir Med 2013; 107(10):1481–1490.

- Johansson G, Stallberg B, Tornling G, Andersson S, Karlsson GS, Falt K, et al.Asthma treatment preference study: a conjoint analysis of preferred drug treatments. Chest 2004; 125(3):916–923.

- Kaiser H, Parasuraman B, Boggs R, Miller CJ, Leidy NK, O'Dowd L. Onset of effect of budesonide and formoterol administered via one pressurized metered-dose inhaler in patients with asthma previously treated with inhaled corticosteroids. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008; 101(3):295–303.

- Sovani MP, Whale CI, Oborne J, Cooper S, Mortimer K, Ekstrom T, et al.Poor adherence with inhaled corticosteroids for asthma: can using a single inhaler containing budesonide and formoterol help? Br J Gen Pract 2008; 58(546):37–43.

- van der Palen J, Klein JJ, van Herwaarden CL, Zielhuis GA, Seydel ER. Multiple inhalers confuse asthma patients. Eur Respir J 1999; 14(5):1034–1037.

- Doyle S, Lloyd A, Williams A, Chrystyn H, Moffat M, Thomas M, et al.What happens to patients who have their asthma device switched without their consent? Prim Care Respir J 2010; 19(2):131–139.

- Braido F, Baiardini I, Sumberesi M, Blasi F, Canonica GW. Obstructive lung diseases and inhaler treatment: results from a national public pragmatic survey. Respir Res 2013; 14:94.

- Thomas M, Price D, Chrystyn H, Lloyd A, Williams AE, von Ziegenweidt J. Inhaled corticosteroids for asthma: impact of practice level device switching on asthma control. BMC Pulm Med 2009; 9:1.

- Thomas M, Williams AE. Are outcomes the same with all dry powder inhalers? Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2005; (149):33–35.

- Williams AE, Chrystyn H. Survey of pharmacists' attitudes towards interchangeable use of dry powder inhalers. Pharm World Sci 2007; 29(3):221–227.

- Price D. Do healthcare professionals think that dry powder inhalers can be used interchangeably? Int J Clin Pract Suppl 2005; (149):26–29.