Abstract

Background and purpose Cementless total hip arthroplasty is currently favored by many orthopedic surgeons. The design of the porous surface is critically important for long-term fixation. We examined the clinical and radiographic outcome of the cementless titanium hip implant with a bottom coating of apatite-wollastonite containing bioactive glass ceramic.

Methods We retrospectively reviewed 109 hips (92 patients) that had undergone primary cementless total hip arthroplasty with bioactive glass ceramic bottom-coated implants. The mean follow-up period was 7 (3–9) years. Hip joint function was evaluated with the Merle d’Aubigné and Postel hip score, and radiographic changes were determined from anteroposterior radiographs.

Results The mean hip score improved from 9.7 preoperatively to 17 at the final follow-up. The overall survival rate was 100% at 9 years, when radiographic loosening or revision for any reason was used as the endpoint. 3 stems in 2 patients subsided more than 3 mm vertically within 1 year after implantation. Radiographs of the interface of the stem and femur were all classified as bone ingrowth fixation.

Conclusions The short-term results of this study show good outcome for cementless implants with a bottom coating of apatite-wollastonite containing bioactive glass ceramic.

The use of cementless implants in total hip arthroplasty is increasing in many countries. A great deal of effort has gone into the development of new implants that are designed for better cementless fixation. Press-fit total hip implants obtain initial stability by maximum contact with the bone surface of the acetabulum and the internal cortical bone surface of the femoral metaphysis. To achieve long-term fixation of the implant to the host bone by osteointegration into the implant, a variety of surface textures for the implants have been developed; these include plasma-sprayed, grit-blasted, or bead-sintered surfaces (Ryan et al. Citation2006). Once bone apposition to anchor the implant is complete, the implant is stabilized in bone. The addition of a biologically active coating, including a hydroxyapatite (HA) coating, accelerates osteointegration of the implant into the bone and leads to inhibition of subsidence, prevention of proximal stress shielding, resistance to wear particle migration, and reduction of thigh pain (Maheshwari et al. Citation2008).

A glass ceramic containing apatite and wollastonite (AW-GC) was reported to have high mechanical strength and the capability of forming a strong chemical bond with osseous tissue (Kokubo et al. Citation1985, Nakamura et al. Citation1985). Ido et al. (Citation1993) produced 2 types of cementless implants in dogs. One was coated with titanium plasma spray and the other was coated further with AW-GC in the deep layer of the pores and showed better cementless fixation in the early phase. Based on these results, the Q Hip System H6 cementless stem and QPOC Porous Cup (Japan Medical Materials, Osaka, Japan) were produced in 1999 (). This stem is a proximal press-fit uncollared cementless design made from a titanium alloy (Ti6Al2Nb1Ta0.8Mo), with an AW-GC bottom-coated porous surface applied by pure titanium plasma spray, which accepts a 22.2-mm or 26.0-mm zirconia ceramic head (yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia containing 0.25 wt% Al2O3; ISO13356) or a CoCr head. We retrospectively examined the clinical and radiographic outcome of the cementless uncollared AW-GC bottom-coated titanium hip implants after a minimum follow-up of 3 years.

Patients and methods

From February 2002 through December 2007, 102 consecutive patients underwent 121 primary THAs in which cementless uncollared circumferential AW-GC bottom-coated porous-coated titanium hip implants were used. We failed to trace 10 patients (12 hips) for follow-up of more than 3 years, and the remaining 92 patients (78 women, 109 hips) were retrospectively reviewed after obtaining institutional board approval. The mean age at operation was 50 (20–75), height 158 (SD 7.6) cm, and weight 57 (SD 9.9) kg. The diagnosis was secondary osteoarthritis caused by developmental dysplasia or congenital dislocation of the hip in 83 hips, osteonecrosis of the femoral head in 19, rheumatoid arthritis in 3, posttraumatic osteoarthritis in 2, and primary osteoarthritis in 2. The mean follow-up period was 6.8 (3.0–9.4) years.

All operations were performed with a direct lateral approach and a partial trochanteric osteotomy, as reported by Dall (Citation1986). The cementless AW-GC bottom-coated acetabular component (QPOC Porous Cup) was placed, and an acetabular autogenous bulk or chip bone graft with a resected femoral head was performed at the superolateral aspect of the acetabular roof in 82 hips. The bulk bone graft was fixed with 1 or 2 bioresorbable poly(L-lactide)-HA screws (Superfixorb; Takiron, Osaka, Japan). The cementless acetabular liner was made of γ-irradiated, highly cross-linked, ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (CLQC liner; Japan Medical Materials). The femur was prepared using reamers and broaches. Broaches of increasing size were used until an appropriate fit was achieved, and the corresponding stem was the same size as the last broach. The H6 cementless stem was implanted. The stem size ranged from 7 mm to 14 mm (median 11 mm) in width at a point 100 mm distal to the medial edge of the calcar. 88 femoral heads had a diameter of 22.2 mm and 21 had a diameter of 26 mm. All femoral heads were made of zirconia ceramic. All patients received intravenous antibiotics 30 min preoperatively and for 2 days postoperatively. Heparin calcium was used as routine thromboprophylaxis for 7 days.

Standard radiographs were taken after surgery, at 2, 4, 6, and 8 weeks, at 3, 6, and 12 months, and at 6-monthly or yearly intervals thereafter. The prevalence, location, and extent of osteolytic lesions, reactive lines, calcar resorption, pedestal formation, and cortical hypertrophy were determined from anteroposterior radiographs taken at the time of the last follow-up. Calcar resorption (defined as rounding of the calcar) was distinguished from calcar osteolysis (defined as a punched-out, expansive area with a concave shape) (Engh et al. Citation1987). The distance between the most proximal point of the greater trochanter and the proximal apex of the shoulder of the prosthesis along the axis of the femoral stem on anteroposterior digital images of the hip joint was measured for identification of the stem subsidence. Fixation of femoral components was categorized using the criteria described by Engh et al. (Citation1990) as bone ingrowth fixation, stable fibrous fixation, or unstable fixation. Radiographic loosening of the acetabular component was defined as a continuous reactive line at the bone-implant interface or any change in the position of the component over time. Radiographic changes were described with the Gruen zones for the proximal femur and with the DeLee and Charnley zones for the acetabulum. Ossification of the femoral stem was graded according to the Brooker ectopic ossification grading system.

Hip joint function was rated according to the scoring system of Merle d’Aubigné and Postel.

Statistics

Linear mixed model with random effects for subjects was used to evaluate the effect of operation on the Merle d’Aubigné and Postel hip score using the statistical software package R version 2.13.0 (http://www.r-project.org/). Linear mixed model allows inclusion of correlated observations. We used compound symmetry pattern for covariance structures. Significance was set at p < 0.01. Kaplan-Meier survivorship analysis was used to study the implant survival.

Results

The mean operating time was 109 (64–203) min and mean intraoperative blood loss was 360 (30–1140) mL. The hip score improved from 9.7 (SD 1.8) preoperatively to 16.5 (SD 1.5) postoperatively (p = 0. 001). No postoperative complications occurred. None of the patients had an infection or a periprosthetic fracture.

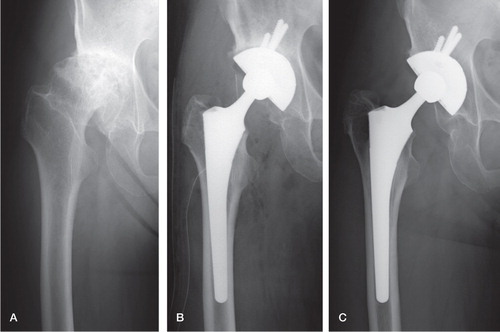

13 hips showed thickening of the femoral cortex near the tip of the stem. 3 hips showed initial stem subsidence of > 3 mm within 1 year after the operation (), but there was no progressive subsidence after this time and this result did not significantly alter the clinical outcome. Grafted bone was remodeled in all cases. There was no reactive line at the bone-implant interface or any change in the position of the acetabular component. Radiographic evaluation of the interface of the stem and femur (Engh’s classification) showed that all 109 hips were classified as bone ingrowth fixation and none were classified as stable fibrous ingrowth. Overall, there was no loosening of either the acetabular or the femoral component (). At the latest follow-up, no femoral or acetabular components had been revised for aseptic loosening or for any other reason. The Kaplan-Meier survivorship analysis, with radiographic loosening or revision as the endpoint, revealed a rate of survival of the femoral and acetabular component of 100% at 9 years. In the worst-case scenario Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, assuming that all 12 hips in 10 patients who were lost to follow-up failed, revealed a 9-year implant survivorship of 90% (95% CI: 85–95) using failure as the endpoint.

Figure 2. A 60-year-old woman with secondary osteoarthritis of the right hip. A. The preoperative Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score was 10 points. B. AW-GC bottom-coated acetabular and femoral components were implanted. C. The Merle d’Aubigné and Postel score improved to 16 points, and bone ingrowth fixation was achieved 9 years after surgery.

Intraoperative crack or fracture of the femur occurred in 6 hips, which were fixed by wiring. 3 postoperative fractures occurred in the greater trochanter, but no additional surgery was needed. Heterotopic ossification was observed in 35 hips, and this was classified as grade 1 in 20, grade 2 in 13, and grade 3 in 2; none required any operation. At the latest follow-up, 4 hips were causing the patient mild thigh pain, and 1 hip caused moderate thigh pain. Neither infection nor implant failure occurred.

Discussion

Clinical and radiographic outcomes of uncemented THA have been improving, and uncemented implants are increasingly used, although they are still being developed further. Long-term success depends partly on the initial mechanical stability of the implants used to improve overall fixation by osteointegration. Titanium and its alloys are used widely because of their biocompatibility, high corrosion resistance, and low elastic modulus, which is close to that of bone. To provide a high friction surface for physical interlocking at the implant-bone interface and to enhance bone-bonding activity of the titanium implants, porous structures on the surface of the implant have been developed with the use of plasma-sprayed, grid-blasted, fiber-metal or bead-sintered methods. HA is now coated on the porous implant surface. HA promotes direct bonding between the implant and the bone because of its good osteoconductivity. Previous studies have reported on the effectiveness of HA coating of total hip implants regarding early bone-bonding ability (Geesink et al. Citation1987, Cook et al. Citation1988). HA coating contributes to early implant stability and reduction of subsidence risk and thigh pain, and inhibition of distribution of wear particles through the bone-implant interface (Kroon and Freeman Citation1992, Rahbek et al. Citation2001, Chambers et al. Citation2007, Epinette and Manley Citation2008). However, a number of concerns have been raised about the use of this coating on porous-surfaced implants. These include a reduction in the space available for bone ingrowth, relatively poor bonding between the substrate and the HA coating layer, and relatively rapid degradation of HA, which produces HA debris and induces third-body wear (Bloebaum et al. Citation1994, Morscher et al. Citation1998, Liu et al. Citation2000). A recent report by Lazarinis et al. (Citation2011) showed that the use of HA coating did not enhance 10-year implant survival.

AW-GC is a bioactive glass ceramic containing wollastonite and oxyapatite as the major components. This ceramic has excellent biocompatibility and a great ability to form tight chemical bonds with living bone (Nakamura et al. Citation1985). Analysis of the bone-bonding ability of AW-GC coated on titanium alloy by the plasma-spray technique and implantation into the tibial bones of mature rabbits showed that AW-GC had earlier bone-bonding ability and greater mechanical strength through the formation of the Ca-P-rich layer. Kitsugi et al. (Citation1989) reported an increase in the load to failure of specimens containing AW-GC in segmental replacement of the rabbit tibia under load-bearing conditions. Yamamuro and Takagi (1991) studied the effect of AW-GC coating on titanium plasma spray-coated implants under loading conditions and found that AW-GC coating only on the bottom of the porous surface had greater bonding strength than fully AW-GC-coated and uncoated implants. A study of cementless total hip implants coated with titanium plasma spray followed by AW-GC bottom coating in dogs showed that bone had grown in the deepest part of the porous layer 1 month after implantation, which was earlier than in those without AW-GC bottom coating (Ido et al. Citation1993).

Titanium and its alloys are currently used in a variety of orthopedic implants. Ti6Al4V has good mechanical properties, but vanadium has been proven to be cytotoxic (Sabbioni et al. Citation1991). The Ti6Al2Nb1Ta0.8Mo alloy has been adopted for the K-MAX Q Hip System H6 stem and QPOC socket. This titanium alloy has 870 MPa in tensile strength, 790 MPa in yield strength, and 108 MPa in Young’s modulus, values that are similar to those of Ti6Al4V (860 MPa, 795 MPa, and 110 MPa, respectively). By contrast, the fatigue strength (490 MPa) of Ti6Al2Nb1Ta0.8Mo is greater than that of Ti6Al4V (410 MPa), allowing reduction of the neck diameter to 9 mm. Reduced neck diameter may contribute to an increased oscillation angle, which should prevent dislocation and reduce the generation of polyethylene wear particles. Further studies will be needed to evaluate the effect of reduced neck diameter on the clinical and radiographic outcomes.

The K-MAX Q Hip System H6 stem is a cementless metaphyseal-fitting device that was designed to fit into the Japanese femur and to minimize stress shielding and abnormal bone reaction. The stem has a proximal circumferential pure titanium plasma-sprayed porous coating with AW-GC bottom coating, and the acetabular component (QPOC socket) has the same coating. The pore size of this coating is 350–450 μm, which is suitable for osteointegration (Bram et al. Citation2000, Citation2006, Xue et al. Citation2007). It can be expected that rapid bony ingrowth into the porous layer will lead to early mechanical anchoring between the bone and the porous layer. In our study, we observed neither progressive subsidence nor osteolysis. To our knowledge, our study is the first to evaluate the clinical and radiographic results associated with AW-GC bottom-coated THA prostheses implanted in humans. The clinical outcome after a mean follow-up of 7 years was excellent. Radiographs showed good osteointegration and implant fixation in the proximal stem and acetabular regions and no progressive radiolucency or osteolysis. However, calcar resorption was found in 102 of 109 hips and cortical hypertrophy was found in 13 hips. Further improvement of the stem design and shape is required for optimal load distribution.

The present study had some limitations. First, a substantial number of patients were lost, and the follow-up period was relatively short. Secondly, the influence of AW-GC bottom coating on implant fixation in the early period after implantation has not been studied in retrieved implants.

In conclusion, we found that a proximal circumferential porous-coated femoral prosthesis and an acetabular prosthesis with AW-GC bottom coating were stable after implantation. AW-GC may give early bone bonding and may be of advantage for initial stability. The optimal combination of surface structure and surface chemistry is promising for improvement of the initial and long-term stability of cementless implants.

KS, YK, TN, and SM analyzed the data, and participated in the writing of the manuscript. KTK analyzed the data statistically. HA coordinated the study, analyzed the data, and participated in the writing of the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Bloebaum RD, Beeks D, Dorr LD, Savory CG, DuPont JA, Hofmann AA. Complications with hydroxyapatite particulate separation in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1994; (298): 19-26.

- Bram M, Stiller C, Buchkremer HP, Stover D, Baur H. High-porosity titanium, stainless steel, and superalloy parts. Adv Eng Mater 2000; 2: 196-9.

- Bram M, Schiefer H, Bogdanski D, Koller M, Buchkremer HP, Stover D. Implant surgery: how bone bonds to PM titanium. Metal Powder Report 2006; 61 (2): 26-31.

- Chambers B, St Clair SF, Froimson MI. Hydroxyapatite-coated tapered cementless femoral components in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22: 71-4.

- Cook SD, Thomas KA, Kay JF, Jarcho M. Hydroxyapatite-coated porous titanium for use as an orthopedic biologic attachment system. Clin Orthop 1988; (230): 303-12.

- Dall D. Exposure of the hip by anterior osteotomy of the greater trochanter. A modified anterolateral approach. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1986; 68 (3): 382-6.

- Engh CA, Bobyn JD, Glassman AH. Porous-coated hip replacement. The factors governing bone ingrowth, stress shielding, and clinical results. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1987; 69: 45-55.

- Engh CA, Glassman AH, Suthers KE. The case for porous-coated hip implants. The femoral side. Clin Orthop 1990; (261): 63-81.

- Epinette JA, Manley MT. Uncemented stems in hip replacement – hydroxyapatite or plain porous: does it matter? Based on a prospective study of HA Omnifit stems at 15-years minimum follow-up. Hip Int 2008; 18: 69-74.

- Geesink RG, de Groot K, Klein CP. Chemical implant fixation using hydroxyl-apatite coatings. The development of a human total hip prosthesis for chemical fixation to bone using hydroxyl-apatite coatings on titanium substrates. Clin Orthop 1987; (225): 147-70.

- Ido K, Matsuda Y, Yamamuro T, Okumura H, Oka M, Takagi H. Cementless total hip replacement. Bio-active glass ceramic coating studied in dogs. Acta Orthop Scand 1993; 64 (6): 607-12.

- Kitsugi T, Yamamuro T, Kokubo T. Bonding behavior of a glass-ceramic containing apatite and wollastonite in segmental replacement of the rabbit tibia under load-bearing conditions. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1989; 71: 264-72.

- Kokubo T, Ito S, Shigematsu M, Sakka S and Yamamuro T. Mechanical properties of a new type of apatite-containing glass-ceramic for prosthetic application. J Mat Sci 1985; 20 (6): 2001-4.

- Kroon PO, Freeman MA. Hydroxyapatite coating of hip prostheses. Effect on migration into the femur. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1992; 74: 518-22.

- Lazarinis S, Kärrholm J, Hailer NP. Effects of hydroxyapatite coating on survival of an uncemented femoral stem. A Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register study on 4,772 hips. Acta Orthop 2011; 82(4):399-404

- Liu X, Chu PK, Ding C. Surface modification of titanium, titanium alloys, and related materials for biological applications. Mater Sci Eng 2000; 47: 49-121.

- Maheshwari AV, Ranawat AS, Ranawat CS. The use of hydroxyapatite on press-fit tapered femoral stems. Orthopedics 2008; 31 (9): 882-4.

- Morscher EW, Hefti A, Aebi U. Severe osteolysis after third-body wear due to hydroxyapatite particles from acetabular cup coating. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1998; 80: 267-72.

- Nakamura T, Yamamuro T, Higashi S, Kokubo T, Ito S. A new glass-ceramic for bone replacement: evaluation of its bonding to bone tissue. J Biomed Mater Res 1985; 19: 685-98.

- Rahbek O, Overgaard S, Lind M, Bendix K, Bunger C, Soballe K. Sealing effect of hydroxyapatite coating on peri-implant migration of particles. An experimental study in dogs. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2001; 83: 441-7.

- Ryan G, Pandit A, Apatsidis DP. Fabrication methods of porous metals for use in orthopaedic applications. Biomaterials 2006; 27 (13): 2651-70. Epub 2006 Jan 19.

- Sabbioni E, Pozzi G, Pintar A, Casella L, Garattini S. Cellular retention, cytotoxicity and morphological transformation by vanadium(IV) and vanadium(V) in BALB/3T3 cell lines. Carcinogenesis 1991; 12 (1): 47-52.

- Xue W, Vamsi Krishna B, Bandyopadhyay A, Bose S. Processing and biocompatibility evaluation of laser processed porous titanium. Acta Biomater 2007; 3: 1007-18.

- Yamamuro T, Takagi T. Bone-bonding behavior of biomaterials with different surface characteristics under load-bearing conditions. In: Bone biomaterial interface (Ed. David JE) 1991;Toron University Press:Toronto406-14.