Abstract

Background and purpose Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) is an established method of treating isolated gonartrosis. Modern techniques such as computer-assisted surgery (CAS) and minimally invasive surgery (MIS) are attractive complementary methods to UKA. However, the positioning of the components remains a concern. Thus, we performed a prospective study to assess whether there was deviation between the navigated implant position and the final implant position.

Patients and methods We performed UKA with MIS and CAS in 13 patients. By comparing intraoperative navigation data with postoperative computed tomography (CT) measurements, we calculated the deviation between the computer-assisted implant position and the final 3-D implant position of the femoral and tibial components.

Results The computer-assisted placement of the femoral and tibial component showed adequate position and consistent results regarding flexion-extension and varus-valgus. However, regarding rotation there was a large variation and 6 of 10 patients were outside the target range for both the femoral component and the tibial component.

Interpretation Difficulties in assessing anatomical landmarks with the CAS in combination with MIS might be a reason for the poor rotational alignment of the components.

The advantages of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) such as less blood loss, shorter hospital stay, shorter time to recovery, superior kinematics, better range of motion, and bone stock preserving capacity are well documented (Saccomanni Citation2010). On the other hand, UKA has a longer learning curve and surgeons usually perform fewer surgeries a year; it is therefore associated with a higher risk of complications such as component malpositioning performed with minimally invasive (MIS) technique (Lindstrand et al. Citation2000, Romanowski and Repicci Citation2002).

UKA has been controversial since its introduction in the 1970s (Deshmukh and Scott Citation2001), when polyethylene wear (Collier et al. Citation1991) and loosening—partially due to suboptimal component positioning (Moreland Citation1988, Bathis et al. Citation2004)—were the predominant failure mechanisms. However, recent reports have shown more promising results (Hollinghurst et al. Citation2006, Griffin et al. Citation2007), and there has been renewed interest in UKA in recent years (Bert Citation2005). Part of this can be explained by improved component design and surgical technique, but MIS (Laskin Citation2001) especially may have had a key role in this trend. Proper and consistent implant positioning is vital, and computer-assisted surgery (CAS) has been suggested to improve the accuracy of implant positioning (Rosenberger et al. Citation2008). Few studies have assessed the implant positioning of navigated UKAs operated with MIS technique (Perlick et al. Citation2004, Kim et al. Citation2005, Konyves et al. Citation2010) and, as far as we know, none have assessed it with three-dimensional (3-D) CT.

We determined the degree of 3-D deviation between the navigated implant position and the final implant position in UKA performed with MIS technique.

Patients and methods

In a prospective pilot study, 13 consecutive patients (7 women) with a median age of 65 (50–76) years underwent cemented primary UKA (Preservation; Depuy Inc, Warsaw, IN) using a computer-assisted navigation system (VectorVision; BrainLab, Munich, Germany) in combination with a minimally invasive incision. 2 senior surgeons (MH and LW) performed all surgeries.

All patients met the inclusion criteria: radiographic medial osteoarthrosis (OA), intact cruciate ligaments, flexion contracture of less than 10 degrees, varus deformity of less than 10 degrees, and symptoms of medial arthritis that warranted joint replacement. 2 patients were excluded: in 1 patient, the tracker loosened during surgery and was thus not navigated; in the other patient, only the tibia was measured peroperatively due to technical difficulties with the CAS software program. In one patient, the rotational component position was not measured postoperatively.

The navigation system used was an image-free instrumentation tool for determination of the component position and mechanical alignment intraoperatively by localizing the center of the hip, knee, and ankle.

Computer-assisted surgery

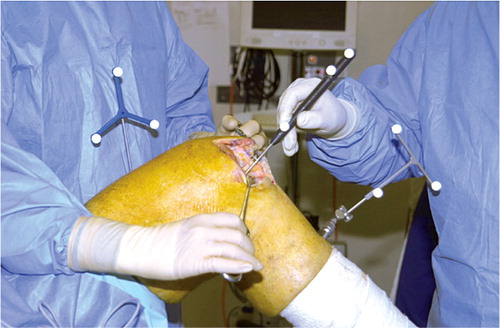

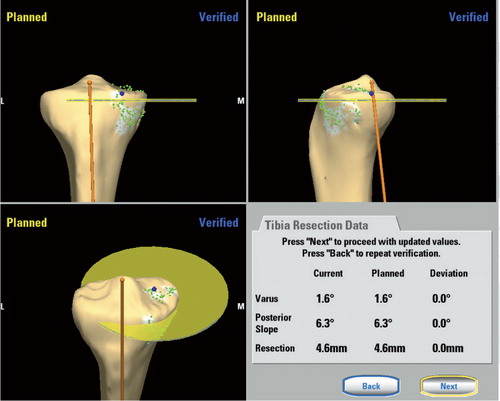

After exposing the knee through a medial parapateller arthrotomy of not more than 8 cm (Repici and Eberle 1999), 2 passive trackers were rigidly fixed to the femur and tibia and the registration process was carried out (). The hip was rotated to determine the center of the hip. Specific landmarks of the knee were digitized to determine the center of the knee, and these points were marked with 1.0-mm tantalum balls in the femur and in the tibia, inserted with an injection gun specially made for this purpose. They were placed in the subchondral bone, marking the location of the point that we registered with our Ci pointer in the navigation system as the center of the tibial plateau and the center of the distal femur. The center of the distal femur was identified as a point slightly medial to the anterior aspect of the femoral notch and the center of the proximal tibia was identified as the posterior aspect of the ACL insertion on the tibial plateau according to the manual for the Ci navigation system. Since the definition of these points is somewhat imprecise, we chose to mark this point with a tantalum ball in order to be able to identify and use the same point when we made our postoperative measurements at the postoperative CT examination. The rotation of the femur was referenced from the transepicondylar axis. The landmarks used to determine the rotation of the tibia were the AP direction of the tibia and the most anterior, medial, and posterior aspects of the medial tibial plateau. The lateral and medial malleolus were localized to define the center of the talus. The computer created a virtual model from the supplemented registration data. The orientation of the cutting blocks was determined using the navigation system (), and after bone resection the cutting planes were documented.

Computed tomography measurements

A CT scan was performed in each patient postoperatively. The scans were made on a General Electric Volume CT (64-slice CT), with a slice thickness of 0.625 mm, 120 kV, 200 mA, 0.6-s rotation time, a collimation width of 40 mm, and a spiral pitch factor of 0.98. The images were then reconstructed with a “bone” algorithm in three planes.

The scan included 3 anatomical regions: (1) the femoral head, (2) the knee, and (3) the ankle. A radiologist (JC) defined the following anatomical landmarks: center of the hip, knee, ankle, and posterior femoral condylar plane. Femoral implant landmarks (antero-superior apex, distal peak, and postero-superior corner) and tibial implant landmarks (anterior-inferior corner, medial-inferior border, and posterior-inferior corner) were used. The position of the femoral component was calculated using the center of the hip, knee, and ankle, the posterior femoral condylar plane, and landmarks on the femoral implant. Subsequently, position of the the tibial component was calculated using the center of the hip, knee, and ankle, the posterior femoral condylar plane, and landmarks on the tibial implant.

Varus/valgus, flexion/extension, and external/internal rotation of both the femoral and tibial components were assessed and expressed as average values. We used the anatomical transepicondylar line to determine the rotation of the femoral component intraoperatively with CAS, and measured the final femoral implant position on postoperative CT scan using the posterior condylar plane.

The average deviation between the intraoperative navigation value and the actual postoperative implant position as measured with CT scan was calculated. We counted how many patients were outside (in any direction) of an arbitrary target range of 3 degrees from the desired original intraoperative CAS measurement. Although this value is an arbitrarily defined safety zone for satisfactory implant position, it is based on theoretical considerations—as errors in CAS, movements of the cutting block/saw, and the cementing of components contribute to differences in peroperative and postoperative measurements (Catani et al. Citation2008).

Ethics

All patients agreed to participate in the trial and ethical approval was obtained.

Results

Of the 11 patients, component rotation could only be assessed in 10 patients due to loss of component rotation measurement in one patient. All patients showed similar alignment values for the components in varus-valgus and flexion-extension when comparing peroperative component position (as measured with the aid of navigation) with postoperative CT measurements. Regarding the rotation of the components, there was great variation in the positioning and a large difference between peroperative and postoperative measurements. 8 of 10 patients had a rotational deviation of the femoral component of more than 3 degrees, and 6 of 10 patients had a rotational deviation of the tibial component of more than 3 degrees ( and ).

Table 1. Results for femoral component positioning in varus-valgus, extension-flexion, and rotation as measured with 3-D CT

Table 2. Results for tibial component positioning in varus-valgus, flexion-extension, and rotation as measured with CT

Discussion

The importance of proper component positioning for the long-term survival of TKR is well known. In TKR, a threshold of 3 degrees of deviation in the coronal plane has been reported to increase the risk of loosening (Mason et al. Citation2007). Some reports have shown the significance of accurate alignment in varus-valgus alignment in relation to the survivorship of the prosthesis in UKA (Weale et al. Citation2000, Deshmukh and Scott Citation2001) where 50% of the cases requiring revision were due to overcorrection (Barett and Scott Citation1987, Chakrabarty et al. Citation1998). To the best of our knowledge, there have been no previous reports on navigated MIS UKA in which the component positioning has been determined postoperatively with 3-D CT scan.

We found a large deviation between intraoperative CAS and postoperative CT scan measurements for the rotational position of both the tibial and the femoral component. A similar result was found in a recent study assessing the tibial component rotation in UKR using CT scan (Servien et al. Citation2011). One reason for the large variation in the rotational plane in MIS UKA could be the difficulty in identifying landmarks. The epicondyles and Whiteside’s line are not as visible as in a standard approach and are therefore less reliable. A recent report on TKR showed a considerable difference in the rotational plane between the intraoperative CAS component position and postoperative CT measurements (van der Linden-van der Zwaag et al. Citation2011). With our CAS system, it is not possible to measure the final position of the components after cementing. Nonetheless, the malpositioning was only found in the rotational plane and not in the 2 other directions and was therefore probably not related solely to the cementing technique. It is possible that improving the navigation system we used in this study, or using another system, might have yielded better results.

Overall, little has been reported regarding rotational alignment, even though it plays an important role in knee kinematics (Schnurr et al. Citation2009). The landmarks in the coronal plane are clinically and radiographically well defined and the long-term effects of malpositioning of the UKA components in terms of survival are well documented (Ridgeway et al. Citation2002). However, the landmarks for rotational UKA component positioning are less well defined and the clinical significance of malrotation is not fully understood—although it has been suggested as a major cause of pain in TKR (Nicoll and Rowley Citation2010).

The advantage of UKA might be enhanced with MIS technique. According to the literature, the rationale for this technique is less muscular damage, resulting in faster rehabilitation and less pain. We used the MIS technique because it is frequently used in UKA, although this might stress the surgeon’s ability and thus increase the risk of component malpositioning, compromising the long-term result. In the present study, MIS UKA performed with CAS had the advantages of a less invasive surgery with no component malpositioning, in varus-valgus and flexion-extension. We do not know whether a standard approach would have resulted in better component positioning, but comparison between MIS and a standard surgical approach was not within the scope of this study.

One weakness of our pilot study was that it was underpowered and lacked a control group. The advantage was that fewer patients were put at risk if the results were not encouraging. Our intention was to conduct a randomized controlled study comparing conventional and navigated technique, but the results of this pilot study have not been promising enough to encourage us to proceed with it.

NM-C: writing of the manuscript; JC: writing of CT method and CT measurements; LW and MH: study design and performance of all surgeries. All authors: data analysis and review of the manuscript.

We thank Depuy, Johnson and Johnson, Sweden for financial support that enabled us to perform the CT measurements.

No competing interests declared.

- Barett WP, Scott RD. Revision of failed unicondylar knee arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1987; 69: 1328.

- Bathis H, Perlick L, Tingart M, Luring C, Zurakowski D, Grifka J. Alignment in total knee arthroplasty. A comparison of computer-assisted surgery with the conventional technique. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2004; 86: 682-7.

- Bert JM. Unicompartmental knee replacement. Orthop Clin North Am 2005; 36: 513-22.

- Catani F, Biasca N, Ensini A, Leardini A, Bianchi L, Digennaro V, Giannini S. Alignment deviation between bone resection and final positioning in computer-navigated total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2008; 90 (4):765-71.

- Chakrabarty G, Newman JH, Ackroyd CE. Revision of unicompartmental arthroplasty. Clinical and technical considerations. J. Arthroplasty 1998; 13: 191.

- Collier JP, Mayor MB, McNamara JL, Surprenant VA, Jensen RE. Analysis of the failure of 122 polyethylene inserts from uncemented tibial knee components. Clin Orthop 1991; (273): 232-42.

- Deshmukh RV, Scott RD. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: long-term results. Clin Orthop 2001; [392]: 272-8.

- Griffin T, Rowden N, Morgan D, Atkinson R, Woodruff P, Maddern G. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty for the treatment of unicompartmental osteoarthritis: a systematic study. ANZ J Surg 2007; 77: 214-21.

- Hollinghurst D, Stoney J, Ward T, Gill HS, Newman JH, Murray DW, Beard DJ. No deterioration of kinematics and cruciate function 10 years after medial unicompartmental arthroplasty. Knee 2006; 13: 440-4.

- Kim SJ, MacDonald M, Hernandez J, Wixson RL. Computer assisted navigation in total knee arthroplasty: improved coronal alignment. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20: 123-31.

- Konyves A, Willis-Owen C, Spriggins A. The long-term benfit of computer-assited surgical navigation in unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg Res 2010; 5: 94.

- Laskin RS. Unicompartmental knee replacement some unanswered questions. Clin Orthop 2001; (392): 267-71.

- Lindstrand A, Stenstrom A, Ryd L, Toksvig-Larsen S. The introduction period of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty is critical: a clinical, clinical multicentered, and radiostereometric study of 251 Duracon unicompartmental knee arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty 2000; 15: 608-16.

- Mason JB, Fehring TK, Estok R, Banel D, Fahrbach K. Meta-analysis of alignment outcomes in computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty surgery. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22: 1097-106.

- Moreland JR. Mechanisms of failure in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1988; (226): 49-64.

- Nicoll D, Rowley DI. Internal rotational error of the tibial component is a major cause of pain after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010; 92 (9):1238-44.

- Perlick L, Bäthis H, Tingart M, Perlick C, Luring C, Grifka J. Minimally invasive unicompartmental knee replacement with a nonimage-based navigation system. Int Orthop (SICOT) 2004; 28: 193-7.

- Repicci GD, Eberle RW. Minimally invasive surgery technique for unicondylar knee arthroplasty. J South Orthop Assoc 1999; 8: 20-7.

- Ridgeway SR, McAuley JP, Ammeen DJ, Engh GA. The effect of alignment of the knee on the outcome of unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2002; 84 (3):351-5.

- Romanowski MR, Repicci JA. Minimally invasive unicondylar arthroplasty: eight-year follow-up. J Knee Surg 2002; 15: 17-22.

- Rosenberger RE, Fink C, Quirbach S, Attal R, Tecklenburg K, Hoser C. The immediate effect of navigation on implant accuracy in primary mini-invasive unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Traumatol Arthrosc 2008; 16 (12):1133-40.

- Saccomanni B. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a review of literature. Clin Rheumatol 2010; 29: 339-46.

- Schnurr C, Nessler J, Konig DP. Is referencing the posterior condyles sufficient to achieve a rectangular flexion gap in total knee arthroplasty? Int Orthop 2009; 33: 1561-5.

- Servien E, Fary C, Lustig S, Demey G, Saffarini M, Chomel S, Neyret P. Tibial component rotation assessment using CT-scan in medial and lateral unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Orthop Tramatolog Surg Res 2011; 97 (3):273-5.

- van der Linden-van der Zwaag HM, Bos J, van der Heide HJ, Nelissen RG. A computed tomography based study on rotational alignment accuracy of the femoral component in total knee arthroplasty using computer-assisted orthopaedic surgery. Int Orthop 2011; 35 (6): 845-50.

- Weale AE, Murray DW, Baines J, Radiological changes 5 years efter unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2000; 82: 996.