Abstract

Background and purpose Patient and implant registries are important clinical tools in monitoring and benchmarking quality of care. For comparisons amongst registries to be valid, a common data set with comparable definitions is necessary. In this study we compared the patients in the Norwegian Knee Ligament Registry (NKLR) and the Kaiser Permanente Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Registry (KP ACLRR) with regard to intraarticular findings, procedures, and graft fixation characteristics reported by the operating surgeon for both primary and revision anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions (ACLRs).

Methods We performed a cross-sectional comparison of the NKLR and KP ACLRR cohorts registered between 2005 and 2010. Aggregate-level data including patient characteristics (age, sex, and laterality), meniscal and cartilage injury patterns and corresponding treatment procedures, choice of graft, and fixation characteristics (type and component material) were shared between registries. Descriptive analyses were then conducted.

Results During the study period, 11,217 ACLRs were registered in the NKLR and 11,050 were registered in the KP ACLRR. In the NKLR, hamstring autograft was used more (68% vs. 30%) for primary ACLRs and allograft was used less (0.2% vs. 41%) than in the KP ACLRR. The KP ACLRR reports more meniscal tears among both primary and revision ACLRs (63% and 50% vs. 49% and 36%). The NKLR reports less use of biodegradable fixation devices.

Conclusions Baseline findings between the NKLR and the KP ACLRR were congruent regarding patient characteristics and most injury patterns, adding to the evidence that comparisons and collaborations between these registries will provide generalizable information to the international orthopedic community. The variation in the treatment, including graft and implant selection and meniscus procedures, between the 2 registries provides opportunities to explore the impact of treatment choices on the outcomes of ACLRs.

Patient and implant registries are appropriate for monitoring and benchmarking processes and outcomes where known variation exists and where inferior performance results in high additional cost or poor quality of life (McNeil et al. Citation2010). In addition to providing information on safety and efficacy of treatment, data from registries can also be used to evaluate whether patients have timely access to care, and whether care is delivered that is consistent with best practice and evidence-based guidelines. The results of registry studies are only as good as the quality of the data collected. Thus, “whether a registry becomes of lasting value depends on it being embedded in the routine process of clinical care, and this in turn depends on a careful decision as to the purpose, together with a design that allows for operational data capture and easy utilization by clinicians with the aim of informing and improving patient care” (Bloom Citation2011).

Comparisons and collaborations between large clinical-quality registries are important for a number of reasons. Comparisons allow understanding of the generalizability of findings to an international orthopedic community. As regards ACLR, collaborations provide numerous opportunities such as evaluation of events of low frequency (e.g. thromboembolic events), introduction of new technology (e.g. new graft fixation devices), and investigation of special populations (e.g. children). To be valid and useful, a common data set with comparable definitions between the registries is necessary.

While Maletis et al. (Citation2011) compared demographic information between the Norwegian Knee Ligament Registry (NKLR) and the Kaiser Permanente Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Registry (KP ACLRR), the purpose of this descriptive study was to compare the 2 patient populations represented by the NKLR and the KP ACLRR with regard to intraarticular findings, procedures, and graft fixation characteristics for both primary and revision ACLRs.

Patients and methods

A cross-sectional comparison of the registered cohorts of the NKLR and KP ACLRR was performed. All primary and revision ACLRs registered in the NKLR from January 2005 to December 2010 and in the KP ACLRR from February 2005 to June 2010 were used in the analysis, independently of the number of additional ligament reconstructions (e.g. multi-ligament reconstructions). Time frames were slightly different due to the different annual report schedules for the registries and their starting months.

Data sources

The NKLR started to collect data in 2004; by December 2010, 11,217 cases had been registered. The NKLR is a national registry covering 5.0 million people. It collects information from 57 hospitals and private surgery clinics and it has had 85% participation compliance since 2006 (Granan et al. Citation2008). The KP ACLR covers 8.9 million members and collects information from 42 hospitals and ambulatory surgery centers in 8 geographical regions of the USA. From its implementation in February 2005 through December 2010, 12,900 cases had been registered, but only data from February 2005 through June 2010 are included in the analysis (n = 11,050). The registry reported 93% voluntary participation in 2010 (Paxton et al. 2012).

Data collection

The ways of data collection in the NKLR and KP ACLRR have been published previously (Granan et al. Citation2008, Paxton et al. Citation2010, 2012). Briefly, the NKLR is a paper-based registry with anonymous contribution by surgeons from all over Norway. The patient’s social security number is used as the unique identifier. The KP ACLRR collects information at the time of surgery using paper forms and data are supplemented with the institution’s electronic health record (EHR). The EHR covers the entire KP membership population. The registry’s unique identifiers are the institution’s region-specific medical record numbers.

The registries were used to identify all variables in this study. Patient characteristics extracted from the registries included age, sex, and laterality. The grafts used for reconstruction were classified as bone-patellar-tendon-bone (BPTB) autograft, hamstring autograft, Achilles’ tendon allograft, BPTB allograft, and other allografts. Fixation devices were classified according to whether they were interference, suspensory, or crosspin fixation and subclassified by their material properties as either biodegradable or non-absorbable. All fixation devices included were reported according to the 5 graft groups. Cases in which the component material or type of fixation could not be established were left as unknown. Meniscus injury (medial, lateral, or both) and the type of procedure performed in each case were also recorded. The types of procedures investigated in each registry included: repair, menisectomy, trephination, rasping (only KP ACLRR), left in situ, and unknown. Cartilage injury and location were collected and the respective procedures were recorded. The location was divided into 6 groups: patella, trochlea, medial and lateral femoral condyle, and medial and lateral tibial plateau. The cartilage procedures were grouped into debridement, microfracture, other treatment, and no treatment.

Statistics

Aggregate-level data were shared between registries. Missing data were labeled as unknown and classified separately in most of the analyses undertaken. SAS software (version 9.1.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used to analyze the data.

Ethics

Approval from the Internal Review Board and the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics was obtained prior to starting this study. The Kaiser Permanente Internal Review Board number was 5691 and it was approved originally in June 2010. For Norway, the number was 04/00928-13/JTA; the study was approved by the Data Inspectorate as an extension of the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register concession.

Results

During the study period (January 2005 through December 2010), 11,217 ACLRs were registered in the NKLR. 10,468 (93%) were primary ACLRs and 749 (6.7%) were revisions. In the KP ACLRR, between February 2005 and June 2010, 11,050 cases were registered (10,394 primary ACLRs and 656 (5.9%) revisions). The median age of the cohorts was similar; for primary ACLRs, the median age of females was 24 in the NKLR and 25 in the KP ACLRR, and for males it was 29 in both registries. The NKLR had a higher proportion of females in the primary ACLR cohort than in the KP ACLRR (43% vs. 36%). There were equal proportions of females in the revision reconstruction cohorts ().

Table 1. Population characteristics by registry and procedure type

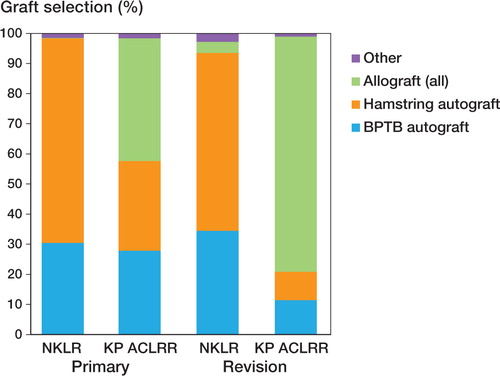

Graft selection by procedure type and registry is shown in . In the NKLR primary ACLR cohort, 30% had a BPTB autograft and 68% had a hamstring autograft. This was a clinically significantly higher proportion than in the KP ACLRR primary reconstruction cohort, where 28% had a BPTB autograft and 30% had a hamstring autograft. A clinically relevant lower proportion of allografts was reported by the NKLR (0.2%) than by the KP ACLRR (41%). A similar distribution of graft usage was found in the revision ACLR cohorts.

lists meniscus injuries and accompanying procedures by registry. Both the primary and revision reconstruction cohorts in the NKLR (49% and 36%, respectively) had less meniscal pathology reported than the in KP ACLRR (63% and 50%, respectively). The same distribution was found for both isolated medial and lateral meniscal tears. In the NKLR primary ACLR cohort, meniscal repairs were less common (medial 24% and lateral 13%) than in the KP ACLRR (medial 28% and lateral 17%). In the NKLR primary ACLR cohort, it was more common to perform either menisectomy (medial 64% and lateral 71%) or no treatment (medial 12% and lateral 16%) than in the KP ACLRR (menisectomy: medial 42% and lateral 51%; no treatment: medial 3% and lateral 6%). In both revision reconstruction cohorts, the same distributions were observed in the menisectomy and “no treatment” groups.

Table 2. Meniscal injury and procedures by registry and procedure type

shows the location of cartilage injuries and accompanying procedures by registry and procedure type. In all 4 groups, “no treatment” was the most frequent treatment, followed by debridement. In the NKLR primary reconstruction cohort, the incidence of “no treatment” varied between 77% for the medial femoral condyle and 94% for the lateral tibial plateau. In the KP ACLRR primary reconstruction cohort, the incidence of “no treatment” was lower, varying between 57% for the patella and 82% for the medial tibial plateau. Debridement was used most frequently in all cartilage locations for both primary and revision cohorts in the KP ACLRR. Microfracture was the only other treatment used in more than 10% of the cases, though only for lateral femoral condyle lesions in revision reconstructions.

Table 3. Cartilage injury location and procedures by registry and procedure type

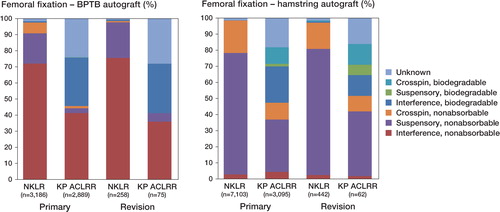

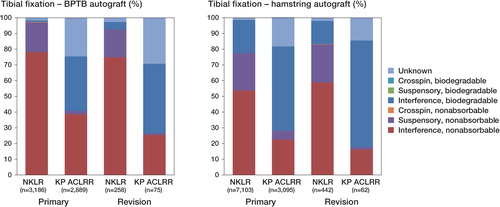

shows primary femoral graft fixations by registry and procedure. In the NKLR cohorts, the frequency of non-absorbable fixation devices varied between 95% and 100% of the cases depending on graft type. In the KP ACLRR cohorts, the frequency of non-absorbable fixation devices varied between 41% and 59% of the cases by graft type. In the 6 BPTB allograft NKLR cases, the distribution of non-absorbable devices was different (17% biodegradable, 17% unknown). shows the tibial graft fixation information. In the NKLR cohorts, the frequency of non-absorbable fixation devices varied between 67% and 100% of the cases. In the KP ACLRR cohorts, the frequency of non-absorbable fixation devices varied between 6% and 48% of the cases. The number of unknown fixation device attributes was higher in the KP ACLRR than NKLR for femoral and tibial fixation (19% and 20% vs. 1.4% and 1.9%, respectively). In the NKLR, biodegradable fixation devices are rarely used on the femoral side, but more frequently on the tibial side.

Discussion

This is the second study to compare the NKLR and the KP ACLRR cohorts. The first study examined preoperative characteristics and the conclusion was that: “Baseline findings are so congruent between the NKLR and the KP ACLRR cohorts that comparisons between these two registries will likely provide information to the orthopedic community that can be generalized” (Maletis et al. Citation2011). The present study focused on intraoperative findings, procedures, and graft fixation patterns in the 2 patient populations represented by the NKLR and the KP ACLRR. No comparison of the procedure outcomes between the registries was undertaken.

This study has several findings of clinical importance. There were similar distributions of grafts amongst the primary and revision reconstructions in the NKLR, with hamstring autografts being the most common graft used. The relative contribution from hamstring autografts has increased every year since the NKLR was established in 2004 (data not shown). In the KP ACLRR, allografts contributed most with proportions ranging from 41% of primary ACLRs to 78% of revision ACLRs. Since increased risk of revision and poorer outcome have been found to be associated with allografts (Kaeding et al. Citation2011, Pallis et al. Citation2012), the high use of allografts may be surprising. However, the literature on this topic lacks high-quality studies, and only 1 systematic review of sufficient quality is currently available (Carey et al. Citation2009). This review was based on non-randomized studies of inferior methodology, and the authors concluded that at least in the short-term, the clinical outcomes of ACLR with allografts are similar to those with autografts. Except for the BPTB autografts used in primary reconstructions, there are clinically relevant differences between the 2 registries in the relative contributions of all 3 main groups of grafts (allografts, hamstring autografts, and BPTB autografts). The differences in choice of graft between the NKLR and the KP ACLRR have not yet been investigated, but they could be due to cultural norms not previously described (e.g. skin incisions, day surgery, or surgical morbidity in general).

We observed more meniscal tears in the KP ACLRR cohort than in the NKLR. This difference has not been explained, and we hypothesize that both activity at the time of injury and gender may have contributed. This analysis is currently under way in the the NKLR and the KP ACLRR. The difference in meniscal injury pattern might also be due to the lack of consistent definitions of meniscal tears and slight changes in how the meniscal tears are reported by the surgeons on the registration forms submitted to the respective registries. While the NKLR wants the surgeons to report whether the tear is on the medial side and/or the lateral side in addition to the type of procedure, the KP ACLRR also wants information about the location of the injury within both menisci. In addition, there are some differences in how these questions are asked. Partial or total menisectomy is the preferred procedure in most cases, followed by repair for all lesions except the lateral tears in the NKLR. These lesions are more likely to be handled with “no treatment” because they mainly represent partial lateral meniscal tears, which usually heal with ACLR. We cannot determine with certainty whether differences exist between registries in the choice of meniscal procedures, due to the number of cases with unknown treatment in the KP ACLRR, which ranges from 17% to 24%. Treatment differences may be due to cultural differences in preference between the 2 national orthopedic communities.

The prevalence of cartilage injuries was similar in both registries, and the way of reporting was close to identical. This variable has been shown to be important for postoperative patient-related outcomes. Røtterud et al. (Citation2012) found that ACL-injured patients with full-thickness cartilage lesions reported worse outcomes and less improvement after ACLR than those without cartilage lesions at 2–5 years of follow-up. Both the Norwegian healthcare system and the KP have similar financial reimbursement strategies. Neither of the registries have incentives that financially benefit surgeons who report more severe injuries. Thus, it is to be expected that surgeons would report to each registry according to their intraoperative findings.

A Norwegian study by Drogset et al. (Citation2005) that found inferior performance of biodegradable graft fixation, and did not “warrant the routine use” of them until larger studies had proven otherwise, may have had an effect on fixation selection in Norwegian surgeons. In Norway, the orthopedic department at each hospital decides whether non-absorbable or biodegradable graft fixations should be used. In the NKLR, biodegradable fixation devices are used less frequently. These differences in choice of graft fixation enable prognostic outcome studies on a range of subgroups that could result in superior or inferior performance of certain products. When interpreting the findings from the NKLR and KP ACLRR regarding fixation devices (both femoral and tibial), this should be done with caution due to the proportion of unknown fixation devices in the KP ACLRR. Since the missing data could bias the estimates of risk associated with certain devices, sensitivity analysis to evaluate the consistency of risk estimations should be carried out in every case.

General considerations about usability, and about the limitations and strengths of registry studies are not discussed in this article; for details see Maletis et al. (Citation2011). Briefly, the specific limitations of this study include some missing and unknown information in the registries and the possible differences in definitions of meniscal injury. In the KP ACLRR, on average 19% of the implant information was missing. These data were missing due to an earlier version of the form used by the registry. In earlier versions, surgeons described fixation devices instead of sending the implant stickers to registry office for direct data entry. This was addressed in a later version of the form, and has substantially increased the degree of data capture for implants. Most of the concurrent injuries described between the registries were similar in the study samples, but the meniscal injury rate was clinically different. While the reasons for this difference between the NKLR and the KP ACLRR are being investigated in a separate study, we suspect this was due to the lack of a standardized definition of meniscal injury.

The strengths of the present study were the large numbers of patients included in each cohort, the variability of the populations included, and the use of prospective data collection mechanisms with data definitions that were mostly consistent. Both registries have a high participation rate, guaranteeing that the samples included are representative of the populations they target, thus ensuring generalizability of the findings to similar community-based practices. Since these registries collect data in a prospective and consistent manner, information bias is minimized. Data definitions are also consistent between the registries, resulting in a lower risk of misclassification bias for the variables studied.

In summary, the baseline findings in the NKLR and the KP ACLRR were found to be congruent regarding patient characteristics and most injury patterns, adding to the evidence that comparisons and collaborations between the patient populations represented by these registries will provide generalizable information to the international orthopedic community. The variation in the treatment, including graft and implant selection and meniscus procedures, between the registries provides opportunities to explore the influence of treatment choices on the outcomes of ACLR in future studies.

Study concept and design: L-PG, MCSI, GBM, TTF, and LE. Extraction of data and preparation of raw data: L-PG and MCSI. Statistical analysis: MCSI. Interpretation of the data: L-PG, MCSI, GBM, TTF, and LE. Drafting of the manuscript (text): L-PG. Drafting of the manuscript (figures and tables): MCSI. Critical revision of the manuscript: L-PG, MCSI, GBM, TTF, and LE.

The Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center was established at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences through generous grants from the Royal Norwegian Ministry of Culture, the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority, the International Olympic Committee, the Norwegian Olympic Committee and Confederation of Sport, and Norsk Tipping AS. The NKLR has been supported by a grant from the Norwegian Medical Association’s Fund for Quality Improvement. We thank Kjersti Steindal for extracting the data from the Norwegian Knee Ligament Registry and Merete Husøy, Ruth Gunvor Wasmuth, and Marianne Wiese for help with data entry.

We thank all the Kaiser Permanente orthopedic surgeons who contribute to the ACLR Registry and the Surgical Outcomes and Analysis Department, which coordinates Registry operations. We also thank Tom S. Huon, BS, for his support with data management and preparation of the study.

No competing interests declared.

- Bloom S. Registries in chronic disease: coming your way soon? Registries--problems, solutions and the future. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011; 50 (1): 4-5.

- Carey JL, Dunn WR, Dahm DL, Zeger SL, Spindler KP. A systematic review of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autograft compared with allograft. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2009; 91 (9): 2242-50.

- Drogset JO, Grontvedt T, Tegnander A. Endoscopic reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament using bone-patellar tendon-bone grafts fixed with bioabsorbable or metal interference screws: a prospective randomized study of the clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med 2005; 33 (8): 1160-5.

- Granan LP, Bahr R, Steindal K, Furnes O, Engebretsen L. Development of a national cruciate ligament surgery registry: the Norwegian National Knee Ligament Registry. Am J Sports Med 2008; 36 (2): 308-15.

- Kaeding CC, Aros B, Pedroza A, Pifel E, Amendola A, Andrish JT, . Allograft versus autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction predictors of failure from a MOON prospective longitudinal cohort. Sports Health: A multidisciplinary approach. Sports Health 2011; 3 (1): 73-81.

- Maletis GB, Granan LP, Inacio MC, Funahashi TT, Engebretsen L. ACL reconstruction registries in the Comparison of community-based U.S. and Norway. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 3) 2011; 93: 31-6.

- McNeil JJ, Evans SM, Johnson NP, Cameron PA. Clinical-quality registries: their role in quality improvement. Med J Aust 2010; 192 (5): 244-5.

- Pallis M, Svoboda SJ, Cameron KL, Owens BD. Survival comparison of allograft and autograft anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction at the United States military academy. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40 (6): 1242-6.

- Paxton EW, Namba RS, Maletis GB, Khatod M, Yue EJ, Davies M, . A prospective study of 80,000 total joint and 5000 anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction procedures in a community-based registry in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) (Suppl 2) 2010; 92: 117-32.

- Paxton EW, Inacio M CS, Kiley ML. The Kaiser permanente implant registries: Effect on patient safety, quality improvement, cost effectiveness, and research opportunities. Perm J 2012; 16 (2) (2): 33-40.

- Røtterud JH, Risberg MA, Engebretsen L, Aroen A. Patients with focal full-thickness cartilage lesions benefit less from ACL reconstruction at 2-5 years follow-up. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2012; 20 (8): 1533-9.