A 66-year old woman (BMI 36) presented for routine follow-up after undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the right knee 12 years ago, and TKA in the left knee 4 years ago. The right TKA was a cementless cruciate-retaining prosthesis (Encore Medical Foundation Knee, femoral component porous coated CoCrMb alloy, tibial component Ti-alloy with 4 screws, PE insert 9 mm). The left TKA was a cemented cruciate-retaining prosthesis (Zimmer Natural Knee II, femoral component CoCrMb alloy, tibial baseplate component Ti-alloy, PE insert 9 mm). The patient reported only mild problems (knee score 88 points, function score 60 points).

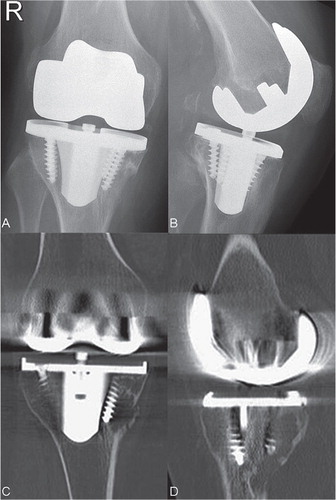

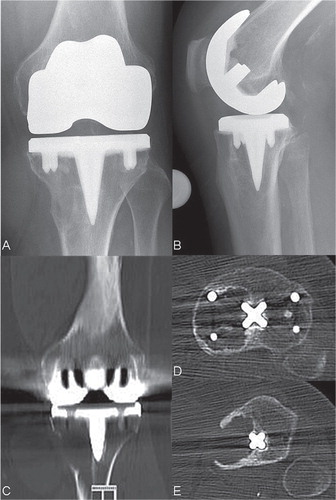

Radiographs and CT scans revealed extensive osteolysis at the proximal medial tibia of both knees ( and ). There was a mild varus malalignment (4°) of both legs. Rotational alignment measured on the CT scans showed a rotational mismatch between femoral and tibial components of 8° (femoral internal rotation) in the right knee and no mismatch (1° of femoral internal rotation) in the left knee.

Figure 1. Anterioposterior and lateral radiograph and CT scans showing osteolysis of the distal right femur and the proximal tibia 12 years after implantation of a cemenless TKA.

Figure 2. Anterioposterior and lateral radiograph and CT scans showing osteolysis of the distal left femur and the proximal tibia 4 years after implantation of a cemented TKA.

Open biopsy was performed bilaterally to rule out a possible malignancy or infection. Microscopic histological examination revealed chronic inflammation and hisitocytic infiltrates in both knees. Polyethylene particles were observed within the cytoplasma of the histiocytes. There was no evidence of metal debris. All microbiological cultures were negative.

During revision, both tibial baseplates were manually assessed as being well fixed to the lateral tibial bone stock, providing no evidence that baseplate loosening was the cause of the osteolysis. However, upon removal of the baseplates, the cortical bone at the proximal medial tibia was observed to be very thin and completely missing in some regions, as already revealed on the CT scans. Osteolytic defects were filled with autologous cancellous bone and augmented with bone cement, and both knees were implanted with a modular constrained TKA prosthesis.

Wear analysis

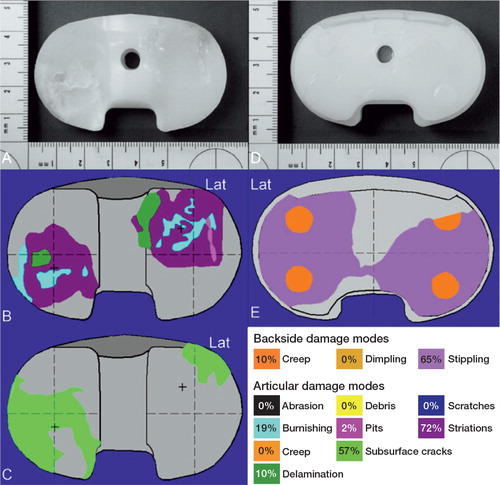

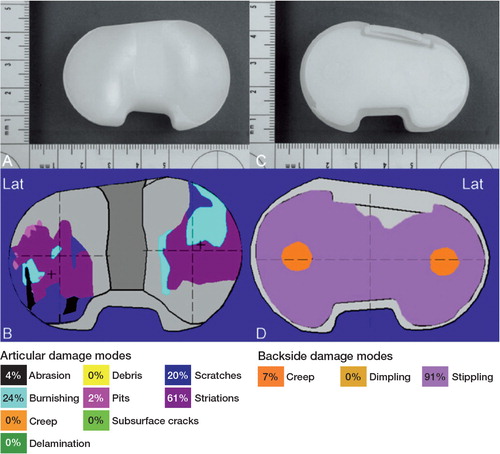

The explanted components were disinfected using a 10% formalin solution, air dried, and shipped to the laboratory for analysis. Gross assessment of the components revealed interface surfaces that were consistent with cementless fixation for the right TKA prosthesis (porous coating with bone attachment) and cement fixation for the left TKA prosthesis (matte finish with cement and bone attachment). Both polyethylene inserts had relatively unconstrained articular conformity with insert modularity provided by anterior tabs to achieve a snap-fit attachment. The tibial component from the right knee had a central screw to further augment insert attachment. Microscopic assessment of the damage modes and damage patterns on the articular and backside surfaces of the polyethylene inserts was completed using a published Damage Mode Atlas (Harman et al. Citation2011) and quantitative techniques (Harman et al. Citation2001, 2007, 2009, 2010).

The polyethylene (PE) inserts had the following distinct features. For both inserts, articular damage occurred on approximately 50% of the articular surface ( and ). The insert from the right knee had regions of delamination (< 10% of the area) on both the medial and lateral surfaces and subsurface cracking (approximately 50% of the area). The insert from the left knee did not have any evidence of gross material failure or fracture. Articular damage patterns were asymmetrically rotated on both inserts, consistent with femoral internal rotation (tibial external rotation) of the right TKA and femoral external rotation (tibial internal rotation) of the left TKA.

Figure 3. Macroscopic photos, damage patterns, and damage modes on the articular surface (panels A–C) and backside surface (panels D and E) of the right insert.

Figure 4. Macroscopic photos, damage patterns, and damage modes on the articular surface (panels A and B) and backside surface (panels C and D) of the left insert.

Damage on the backside surfaces had a roughened, curvilinear stippling pattern covering > 70% of the surface for both inserts, consistent with motion at the modular interface ( and ). Backside damage area on the left insert was larger than on the right insert. There was evidence of protrusions into screw holes for both inserts, consistent with creep deformation due to weight-bearing loads or removal of material on the surrounding surfaces.

Discussion

PE wear debris and the resulting foreign body reaction leading to periprosthetic osteolysis is a common cause of failure in cementless TKA, but it occurs rarely in cemented TKA (Benevenia et al. Citation1998, Engh et al. Citation1992, 1994, Kane et al. Citation1994, Lewis et al. Citation1995, Peters et al. 1992, Rodriguez and Barrack Citation2001, Sanchis-Alfonso and Alcacer-Garcia Citation2001, Vernon et al. Citation2011). Differential diagnoses of osteolysis due to polyethylene wear, periprosthetic infection, and benign or malignant tumors must be considered.

In cemented TKA, only a few cases of excessive osteolysis causing implant failure have been reported (Ries et al. 1994, Robinson et al. Citation1995, Griffin et al. Citation1998, Pagnano et al. Citation2001, Hanna and Thornhill Citation2006). In our case, there was extensive osteolysis in the proximal tibia of both knees, with a strikingly similar bilateral appearance in clinical images. Differences in component fixation, including cemented and uncemented fixation, and differences in the damage patterns on the PE articular surfaces do not suggest that a unique mechanism contributed to the osteolysis. Contrary to expected performance, the osteolysis occurred in the uncemented prosthesis after a much longer time than with the cemented prosthesis, which showed osteolysis after only 4 years. The articular damage patterns on the left polyethylene insert were unremarkable from a wear point of view. The damage modes (dominated by striations, burnishing, and scratching) and the rotated damage pattern are typical patterns for cruciate-retaining TKA with low conformity in both knees (Harman et al. Citation2001, 2007, 2009). In contrast, the articular damage patterns on the right PE insert showed modes of damage (delamination, subsurface cracking) consistent with high-contact stress and material fatigue.

The risk of generating wear debris increased with the in situ lifetime of the right TKA (Engh et al. Citation1992). The similarity in the extent of bone destruction from osteolysis in these bilateral TKAs is inconsistent with the large differences in wear and functional duration. One possible mechanism contributing to the generation of PE debris is malalignment, leading to excessive eccentric wear (Insall and Dethmers Citation1982, Rorabeck Citation1995). In an in vitro simulator study, malalignment of more than 3° (varus or valgus) led to higher PE wear in TKA, which is a major reason for loosening (Loer and Plitz Citation2003). In our case, the alignment of both TKAs was only 1°, suggesting that axial malalignment was not a major contributory factor to the wear. However, the asymmetric articular damage pattern on the right polyethylene insert was consistent with the mismatch of 8° of femoral internal rotation in relation to the tibial component measured on CT scans of the right knee. This mismatch, combined with the knee kinematics that occur during patient activity, produced an extreme anterior lateral damage pattern with delamination noted on the tibial eminence. Such mismatch and asymmetric damage patterns were not noted for the left TKA, suggesting that malalignment was not a major factor contributing to the osteolysis in that knee. Different wear mechanisms and pathways for debris to access the tibial bone have been reported (Surace et al. Citation2002). Wasielewski et al. (Citation1997) assumed that the nonarticular surface wear is the predominant source of the PE debris causing tibial osteolysis. Using autopsy retrievals, Surace et al. (Citation2002) showed that distal penetration of granulomas was aided by the presence of screw holes in cementless prostheses, effectively diverting synovial fluid laden with PE debris from the articular or backside surface away from the tray-bone interface. Conditt et al. (Citation2005) showed that the backside wear was not generated by the extrusion of PE into screw holes within the baseplate, but by abrasion of the underside of the bearing insert creating substantial backside wear that was sufficient to induce osteolysis.

In our case, the backside damage patterns on both PE inserts are consistent with an abrasive mechanism resulting in generation of wear debris and removal of material, to the extent that the alphanumeric labels were generally unreadable. The right knee components, with 4 screw holes in the baseplate and cancellous screws, possibly provided a pathway for the wear debris into the periprosthetic tibial bone (Peters et al. 1992, Ezzet et al. Citation1995, Lewis et al. Citation1995, Rorabeck Citation1995). However, the left knee did not have cancellous screws, and the screw holes in the baseplate were blocked with small plastic disks. Thus, there appear to have been different pathways for wear debris into the proximal tibia in these two knees.

The cement-implant interface, which is postulated to act as a barrier to prevent osteolysis, was dominated by another mechanism, which cannot be explained by our detailed analysis. The mechanism of osteolysis in the cementless TKA, which showed wear consistent with the duration of function, is comparable to published cases (Engh et al. Citation1992, Robinson et al. Citation1995, Hanna and Thornhill Citation2006). The similar appearance of osteolysis in the contralateral cemented TKA only 4 years after implantation does not correlate with the low amount of wear observed, or with the absence of ready access to the periprosthetic bone. Thus, it does not appear to represent a classical “particle disease”. The osteoclastic mediator RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand) has been linked to osteolysis in cemented total hip arthroplasty (Holt et al. Citation2007, Veigl et al. Citation2007). RANKL plays a key role in the development of osteolysis, due to its involvement in the formation of both osteoclasts and foreign body giant cells. However, wear particles have been suggested to act as a stimulus for this process. Koivu et al. (Citation2012) reported osteolysis in early failed total ankle replacement without relevant wear particles which might have been caused by a RANKL-driven chronic foreign body inflammation directed against necrotic autologous tissue. Tissue necrosis (bone and/or soft tissue) might have been caused by local ischemia due to blood vessel damage during the operation, cement-induced tissue necrosis, and/or by obesity causing high mechanical stress. This mechanism may have contributed to the large degree of osteolysis observed in our case.

We thank Leah Nunez at Clemson University Biomedical Engineering Inovation Campus for her macroscopic and microscopic assessments of the retrieved prostheses, and Kathrin Wieczorek of the Department of Pathology University of Dresden for histology work.

The institution of 3 of the authors (JD, SK, JL) has received funding from Smith and Nephew Orthopaedics for monitoring of TKA revision implants.

- Benevenia J, Lee FY, Buechel F, Parsons JR. Pathologic supracondylar fracture due to osteolytic pseudotumor of knee following cementless total knee replacement. J Biomed Mater Res 1998; 43 (4): 473-47.

- Conditt MA, Thompson MT, Usrey MM, Ismaily SK, Noble PC. Backside wear of polyethylene tibial inserts: mechanism and magnitude of material loss. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2005; 87 (2): 326-31.

- Engh GA, Dwyer KA, Hanes CK. Polyethylene wear of metal-backed tibial components in total and unicompartmental knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1992; 74 (1): 9-17.

- Engh GA, Parks NL, Ammeen DJ. Tibial osteolysis in cementless total knee arthroplasty. A review of 25 cases treated with and without tibial component revision. Clin Orthop 1994; (309): 33-43.

- Ezzet KA, Garcia R, Barrack RL. Effect of component fixation method on osteolysis in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1995; (321): 86-91.

- Griffin FM, Scuderi GR, Gillis AM, Li S, Jimenez E, Smith T. Osteolysis associated with cemented total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1998; 13 (5): 592-8.

- Hanna MW, Thornhill TS. Thigh mass and lytic diaphyseal femoral lesion associated with polyethylene wear after hybrid total knee arthroplasty. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006; 88 (11): 2473-8.

- Harman MK, Banks SA, Hodge WA. Polyethylene damage and knee kinematics after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 2001; (392): 383-93.

- Harman MK, Banks SA, Hodge WA. Backside damage corresponding to articular damage in retrieved tibial polyethylene inserts. Clin Orthop 2007; 458: 137-44.

- Harman MK, DesJardins J, Benson L, Banks SA, LaBerge M, Hodge WA. Comparison of polyethylene tibial insert damage from in vivo function and in vitro wear simulation. J Orthop Res 2009; 27 (4): 540-8.

- Harman MK, Schmitt S, Rossing S, Banks SA, Sharf HP, Viceconti M, Hodge WA. Polyethylene damage and deformation on fixed-bearing, non-conforming unicondylar knee replacements corresponding to progressive changes in alignment and fixation. Clin Biomech (Bristol. Avon) 2010; 25 (6): 570-5.

- Harman M, Cristofolini L, Erani P, Stea S, Viceconti M. A pictographic atlas for classifying damage modes on polyethylene bearings. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2011; 22 (5): 1137-46.

- Holt G, Murnaghan C, Reilly J, Meek RM. The biology of aseptic osteolysis. Clin Orthop 2007; (460): 240-52.

- Insall JN, Dethmers DA. Revision of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop 1982; (170): 123-30.

- Kane KR, DeHeer DH, Beebe JD, Bereza R. An osteolytic lesion associated with polyethylene wear debris adjacent to a stable total knee prosthesis. Orthop Rev 1994; 23 (4): 332-7.

- Koivu H, Mackiewicz Z, Takakubo Y, Trokovic N, Pajarinen J, Konttinen YT. RANKL in the osteolysis of AES total ankle replacement implants. Bone 2012; 51 (3): 546-52.

- Lewis PL, Rorabeck CH, Bourne RB. Screw osteolysis after cementless total knee replacement. Clin Orthop 1995; (321): 173-7.

- Loer I, Plitz W. Tibial malalignment of mobile-bearing prostheses--a simulator study. Orthopade 2003; 32 (4): 296-304.

- Pagnano MW, Scuderi GR, Insall JN. Tibial osteolysis associated with the modular tibial tray of a cemented posterior stabilized total knee replacement: a case report. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2001; 83 (10): 1545-8.

- Peters PC, Jr., Engh GA, Dwyer KA, Vinh TN. Osteolysis after total knee arthroplasty without cement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1992; 74 (6): 864-76.

- Ries MD, Guiney W, Jr., Lynch F. Osteolysis associated with cemented total knee arthroplasty. A case report. J Arthroplasty 1994; 9 (5): 555-8.

- Robinson EJ, Mulliken BD, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Alvarez C. Catastrophic osteolysis in total knee replacement. A report of 17 cases. Clin Orthop 1995; (321): 98-105.

- Rodriguez RJ, Barrack RL. Failed cementless total knee arthroplasty presenting as osteolysis of the fibular head. J Arthroplasty 2001; 16 (2): 239-42.

- Rorabeck CH. Mechanisms of knee implant failure. Orthopedics 1995; 18 (9): 915-8.

- Sanchis-Alfonso V, Alcacer-Garcia J. Extensive osteolytic cystlike area associated with polyethylene wear debris adjacent to an aseptic, stable, uncemented unicompartmental knee prosthesis: case report. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2001; 9 (3): 173-7.

- Surace MF, Berzins A, Urban RM, Jacobs JJ, Berger RA, Natarajan RN, Andriacchi TP, Galante JO. Coventry Award paper. Backsurface wear and deformation in polyethylene tibial inserts retrieved postmortem. Clin Orthop 2002; (404): 14-23.

- Veigl D, Niederlova J, Krystufkova O. Periprosthetic osteolysis and its association with RANKL expression. Physiol Res 2007; 56 (4): 455-62.

- Vernon BA, Bollinger AJ, Garvin KL, McGarry SV. Osteolytic lesion of the tibial diaphysis after cementless TKA. Orthopedics 2011; 34 (3): 224.

- Wasielewski RC, Parks N, Williams I, Surprenant H, Collier JP, Engh G. Tibial insert undersurface as a contributing source of polyethylene wear debris. Clin Orthop 1997; (345): 53-9.