Abstract

Background and purpose Bone healing is a complex process influenced by growth factors, cytokines, and other mediators. The regulation of this process is not well understood. In this pilot study, we used microdialysis technology in a critical-size bone defect in rat femurs to determine the feasibility of measuring cytokines and growth factors in the first 24 h after injury.

Methods A 5-mm defect, stabilized by a plate, was created in the femurs of 30 male Wistar rats. The microdialysis probe (with 100 kDa molecular weight cutoff) was inserted into the defect and microdialysates were collected continuously for up to 24 h. Total protein concentration, interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentration, and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) concentration were assessed under different conditions.

Results Microdialysis allowed continuous and consistent protein collection over 24 h from a critical-size bone defect starting at the time of injury. IL-6 was secreted within the first 3 h after the injury. The highest IL-6 concentration (344 pg/mL) was measured between 12 and 15 h after surgery. Addition of bovine serum albumin to the perfusate resulted in detectable concentrations of TGF-β1 ranging from 10 to 23 pg/mL.

Interpretation Continuous sampling over 24 h of proteins from a bone defect directly after the injury is feasible and provides the opportunity for a detailed analysis of the initial stages of bone healing.

Cytokines act as important signaling molecules in response to injury. They are secreted by immune cells and can be found in the extracellular fluid of the damaged tissue immediately after the injury (Gouwy et al. Citation2005). Cytokines are crucial in regulating the early immunological response, cell-to-cell interactions, and inflammatory reactions that take place both systemically and locally at the site of injury (Lefkowitz and Lefkowitz Citation2001). While the systemic inflammatory reaction to injury has been studied intensively (Cox et al. Citation2010), direct measurement of local cytokine concentration in vivo, which could provide an insight into local processes, has not yet been performed successfully (Claes et al. Citation2012).

Microdialysis was originally used for the recovery of small water-soluble molecules from brain (Bellander et al. Citation2004), adipose tissue (Rosdahl et al. Citation1993), or skin (Petersen et al. Citation1992). Continuous sampling in the same individual allows the analysis of time-dependent changes in concentration of these molecules—for example, to monitor the neurotransmitter release—without destroying the sample.

Sampling of cytokines in vivo is challenging because of the inherent technical problems. Low concentration of the cytokines, small sample volume, non-specific binding of the protein to the membrane, and the molecular weight and hydrophobicity of the proteins of interest markedly influence recovery (Clough Citation2005, Helmy et al. Citation2009). The diffusion process across the membrane also depends on the temperature, the molecular weight cutoff of the membrane, the area and composition of the membrane, and on the concentration gradient (Helmy et al. Citation2009). Moreover, proteins of 10 kDa or more hardly pass through a 100-kDa membrane. The recovery rate is usually below 5% at a flow rate of 1 µL/min (Schutte et al. Citation2004). Below the molecular weight cutoff, the quaternary structure and the hydrophobicity of a protein will have an influence on how well it passes through a membrane (Waelgaard et al. Citation2006).

Microdialysis in bone has been limited to monitoring of antibiotics for pharmacokinetics (Stolle et al. Citation2008) and prostaglandin E2 production in response to mechanical loading (Thorsen et al. Citation1996). Furthermore, Bøgehoj et al. (2011) used microdialysis in the femoral head of humans and minipigs to define the metabolic status of the tissue by measuring the concentration of glucose, lactate, and pyruvate.

In the present study, we used microdialysis in a critical-size bone defect in rat femurs to determine the feasibility of investigating cytokines and other inflammatory factors involved in the early stages of bone healing during the first 24 h after injury. The analysis therefore focussed on total protein concentration, interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentration, and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) concentration. To validate the method, our in vivo studies were preceded by in vitro microdialysis of a defined protein solution.

Material and methods

Animal surgery

Approval for conducting the animal experiments was granted by the local animal care committee (24-9168.11-1/2010-22). 30 male Wistar rats with an average body weight of 300 g were obtained from Janvier (Le Genest Saint Isle, France) and held in the animal care unit for at least 7 days before the experiments.

The rats were anesthesized with a solution of ketamine (100 mg/kg body weight) and xylazine (10 mg/kg body weight) intraperitoneally. To maintain the anesthesia over up to 24 h, a permanent catheter was placed intraperitoneally and ketamine/xylazine anesthesia was administered through the catheter every 90–120 min. In addition, a mixture of 0.5 mL 0.9% NaCl solution and 0.5 mL glucose (10%) was administered to avoid hypoglycemia and dehydration. The rats were covered with thin sheets during the experiment to avoid hypothermia.

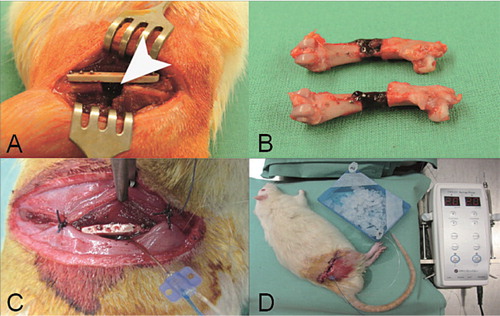

After shaving and disinfection of the right hindlimb, a longitudinal incision of 3 cm was made and the femur was surgically exposed by dissecting the thigh muscles. A titanium-coated polymer plate (RatFix; AO Foundation, Davos, Switzerland) was attached to the femur and a 5-mm bone defect was created with a wire saw. The microdialysis catheter was inserted into the bone defect and fixed to the plate with a suture (). The soft tissues were closed in two layers with absorbable sutures and disinfected again. The rats were killed at the end of experiment.

Figure 1. A. A titanium-coated polymer plate was used to stabilize the defect in the rat femur (arrow). B. Explanted femora with clotted fracture hematoma 24 h after surgery. C. The microdialysis probe was inserted into the defect and fixed to the plate. D. Experimental setting for in vivo microdialysis. The probe was connected to the microdialysis pump. Samples were collected on ice.

In vitro microdialysis

The commercially available CMA/20 microdialysis catheter (CMA Microdialysis AB, Solna, Sweden) with a 4-mm polyethylensulphone membrane and a cutoff of 100 kDa was used for the experiments. Before insertion, the probe was primed with an initial flush (15 min, 5 µL/min). A defined protein solution containing a mixture of 0.4 ng/mL interleukin-6 (IL-6), 0.4 ng/mL transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), 0.4 ng/mL vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA, Sigma-Aldrich, Munich, Germany) was placed in a thermostatically controlled shaker at 37°C. The membrane was perfused in the protein solution for 15 min at the appropriate flow rate and with the corresponding perfusion fluid for equilibration flow rate of 1 µL/min or for 2 h at a flow rate of 2 µL/min, fractionated, and then immediately frozen at –20°C. To determine variations in concentration due to fluid loss from the probe, evaporation, or protein degradation, external protein solution (in which the catheters were situated) was also sampled after 4 h.

In vivo microdialysis

For in vivo experiments, the microdialysis probe was primed with an initial flush for 15 min at a flow rate of 5 µL/min. The membrane was perfused with perfusion fluid (PER, 147 mmol/L NaCl, 4 mmol/L KCl, 2.3 mmol/L CaCl2; CMA Microdialysis AB, Solna, Sweden) or 0.9% NaCl solution at flow rates of 1–2 µL/min using a CMA402 microdialysis pump (CMA Microdialysis). Dextran-70 (abbreviated Dex) (0.01%, 0.04%; Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) or 1% BSA were added to PER during the different parts of the study. To avoid protein degradation, EDTA was added to the collection tube (final concentration 10 mmol/L). Samples were collected on ice, fractionated, and immediately stored at –20°C.

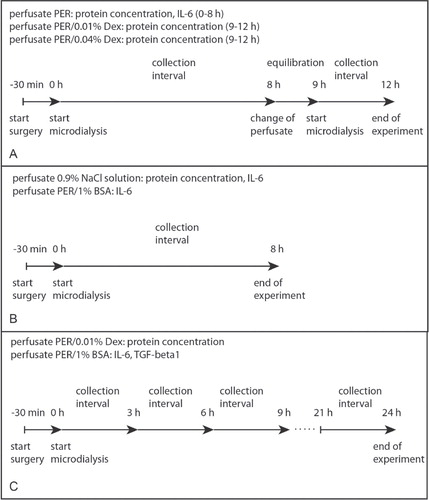

For determination of total protein concentration 19 rats were used: n = 10 for 0.9% NaCl solution (total collection time 8 h); n = 6 for PER (total collection time 8 h); n = 3 for PER/0.01% Dex (total collection time 3 h after microdialysis with PER); n = 3 for PER/0.04% Dex (total collection time 3 h after microdialysis with PER); n = 3 for PER/0.01% Dex (total collection time 24 h, 3-h intervals). For determination of IL-6 and TGF-β1concentration, 11 rats were included: n = 6 for PER/1% BSA (total collection time 8 h); n = 5 for PER/1% BSA (total collection time 24 h, 3-h intervals) ().

Sample analysis

Relative fluid recovery was expressed as the ratio between the sample volume collected and the sample volume calculated. Protein concentration was determined by measurement of the optical density at 280 nm (NanoDrop, Wilmington, DE). Relative recovery was calculated as the concentration of cytokine measured in the microdialysate divided by the concentration of cytokine measured in the external protein solution at the same time point, which was set to 100%.

IL-6, TGF-β1, and VEGF concentrations were analyzed with commercially available ELISA kits (Mouse/Rat/Porcine/Canine TGF-beta1 Quantikine ELISA kit, Rat IL-6 Quantikine ELISA kit, and Rat VEGF Quantikine ELISA kit; R&D Systems, Wiesbaden, Germany). The ELISA assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The detection limits were 21 pg/mL for IL-6, 4.6 pg/mL for TGF-β1, and 8.4 pg/mL for VEGF. 50 µL of the samples were used undiluted.

Statistics

The data were analyzed for normality by Shapiro-Wilk test and expressed as median (range) for in vitro results and as mean with standard deviation (SD) for in vivo results. Paired Student’s t-test was used to test different collection intervals against the first interval (0–3 h). Any p-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

In vitro microdialysis

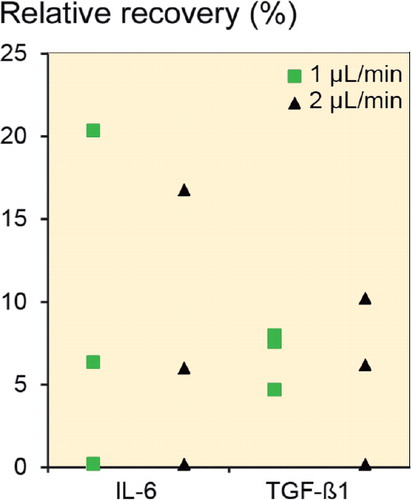

In vitro microdialysis was performed to identify the relative recovery under ideal conditions. PER, PER/1% BSA, PER/0.01% Dex, and 0.9% NaCl solution were used as perfusates at flow rates of 1 µL/min and 2 µL/min. Only when 1% BSA was added to the perfusate could IL-6 and TGF-β1 be detected in the in vitro microdialysate. In all other cases, IL-6 and TGF-β1 concentrations were below the detection limit of the ELISA. VEGF could not be detected in any sample. Relative recovery of IL-6 was 6.4% (0.3–20.4) at 1 µL/min and 6.0% (0.2–17) at 2 µL/min (n = 3, ). The relative recovery of TGF-β1 was also slightly reduced at a flow rate of 2 µL/min in comparison to a flow rate of 1 µL/min (6.2% (0.3–10.2) vs. 7.6% (4.7–8.0)). Recovery was almost unaffected by the flow rate. Thus, a flow rate of 2 µL/min was used during the rest of the study, to increase sample volume.

Determination of fluid recovery

Fluid recovery was studied to determine fluid loss from the microdialysis membrane. Under ideal conditions, the volume in the microdialysis probe should be equal to the volume leaving the microdialysis probe. When PER without additives was used as perfusate, fluid recovery was 98% (SD 1.3) at a flow rate of 2 µL/min. Consequently, no loss of fluid was seen. Addition of Dex or BSA as osmotic reagents did not influence the recovery of fluid. Fluid recovery ranged between 99% and 100% when Dex or BSA was added.

Total protein concentration

Total protein concentration was analyzed only in microdialysates from probes perfused with 0.9% NaCl, PER, or PER/Dex. When using PER as perfusate, the total protein concentration varied between 0.11 mg/mL and 0.32 mg/mL at a flow rate of 1 µL/min (mean 0.22 mg/mL (SD 0.08)) and between 0.05 mg/mL and 0.25 mg/mL at 2 µL/min flow rate (mean 0.12 mg/mL (SD 0.06)). Addition of 0.01% Dex to the perfusate resulted in a slight but not statistically significant increase in total protein concentration (0.33 mg/mL (SD 0.01) at 1 µL/min and 0.22 mg/mL (SD 0.01) at 2 µL/min). The use of isotonic NaCl as perfusate resulted in a total protein concentration of 0.39 mg/mL (SD 0.14). Because no significant differences in protein concentration were detectable, all perfusates could be used for microdialysis.

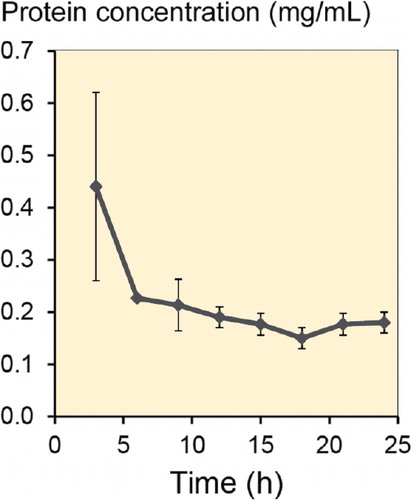

The total protein concentration was also determined in microdialysates recovered over 24 h in 3h-intervals, in 3 rats (). Microdialysis probes were perfused with PER/0.01% Dex. After the first 3 h, total protein concentration was 0.44 mg/mL (SD 0.18). After this period, total protein concentration declined to values between 0.23 mg/mL and 0.15 mg/mL.

IL-6 concentration

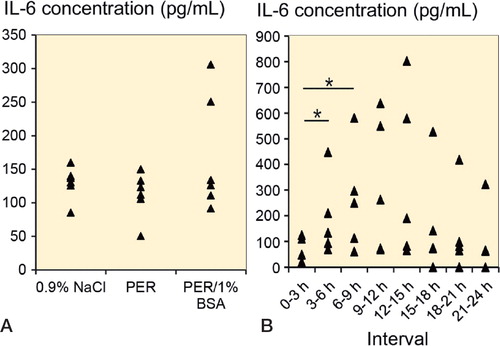

For a focussed analysis of the microdialysate with respect to early reaction to injury, IL-6 and TGF-ß1 concentrations were determined. In a first series (n = 6 for each perfusate), PER, PER/1% BSA, and 0.9% NaCl solution were used as perfusates. Microdialysate was collected for 8 h at a flow rate of 2 µL/min. IL-6 concentration was 140 pg/mL (SD 29) for 0.9% NaCl solution and 124 pg/mL (SD 17) for PER. With addition of 1% BSA to the perfusate, slightly more IL-6 was found (174 pg/mL (SD 83)) (). Sampling over 24 h showed that IL-6 increased further in microdialysates collected from a critical-size bone defect (n = 5). PER/1% BSA was used as perfusate at a flow rate of 2 µL/min. The highest IL-6 concentration (344 pg/mL (SD 330)) was determined between 12 h and 15 h after surgery. A significant increase in IL-6 could be detected between 0 and 3 h, and in the intervals 3–6 h and 6–9 h after injury (p < 0.05) (). IL-6 declined to 130 pg/mL after 24 h of collection.

Figure 5. A. IL-6 concentration from in vivo microdialysates collected from probes perfused with 0.9% NaCl, PER, or PER/1% BSA (n = 6 for each perfusate) for 8 h at a flow rate of 2 µL/min in a critical-size bone defect. B. IL-6 concentration in microdialysates from a critical-size bone defect in 5 animals. Microdialysates were collected in 3-h intervals over 24 h. PER/1% BSA was used as perfusate at a flow rate of 2 µL/min. * p < 0.05.

TGF-β1 concentration

TGF-β1 was not detectable in microdialysates from the critical-size bone defects when PER or 0.9% NaCl solution was used as perfusate. Addition of 1% BSA to PER resulted in detectable concentrations of TGF-β1. TGF-β1 concentration ranged between 10 and 23 pg/mL.

Discussion

To date, in bone, microdialysis has only been used to detect antibiotics (Stolle et al. Citation2008) and prostaglandin E2 (Thorsen et al. Citation1996). To our knowledge, fracture healing has not yet been investigated with this method.

Detection and quantification of cytokines by microdialysis could offer an excellent way of monitoring the first stages of fracture healing, after establishing the experimental setup. We used in vitro microdialysis to determine the ideal perfusates and additives, and to evaluate the recovery of defined proteins. IL-6 and TGF-β1 were chosen because they are cytokines that are induced early during fracture healing (Cho et al. Citation2002, Nyan et al. Citation2010) and affect both osteoblast and osteoclast function. VEGF was included because of its size (of about 45 kDa). Our aim was to determine whether such large proteins—that are known to have a worse recovery—can pass through the membrane (Schutte et al. Citation2004). IL-6 and TGF-β1 could only be detected in microdialysates when 1% BSA was added to the perfusate. Without BSA in the perfusate, IL-6 and TGF-β1 concentration were below the detection threshold of the ELISA. A similar increase in the recovery was also described by Helmy et al. (Citation2009) and Hillman et al. (Citation2005). BSA appears to bind to the proteins when crossing the membrane. Then the higher molecular weight of the BSA-protein complex may prevent it from crossing the membrane towards the external solution. The influence of hydration of the protein solution, through fluid loss over the membrane, on the recovery may be neglected. The perfusate can cross the membrane and dilute the tissue around the catheter, thus reducing the concentration of the proteins (Clough Citation2005). In our experiments, fluid loss was not detected when using perfusates without additives. The recovery rate was almost unaffected by the flow rate. Because the total amount of protein was higher at a flow rate of 2 µL/min than at 1 µL/min, a flow rate of 2 µl/min was used to increase the sample volume for in vivo measurement of IL-6 and TGF-β1.

VEGF could not be detected in any case. We assume that the protein is too large to cross the membrane. The degree of recovery decreases with increasing molecular weight of the protein (Schutte et al. Citation2004). However, the absolute protein concentration also influences sampling (Waelgaard et al. Citation2006). A higher concentration would increase recovery because of a higher concentration gradient, and thus raise the concentration in the in vitro microdialysate above the detection threshold of ELISA. In previous experiments, recovery of VEGF in vitro was 4% at a flow rate of 2 µL/min at room temperature, but the concentration and composition of the protein solution were not reported (Dabrosin et al. Citation2002). We used a mixture of 3 proteins that are known to influence the recovery. Furthermore, VEGF has been detected by microdialysis in an intrauterine model (Licht et al. Citation1998) and in normal breast tissue (Dabrosin Citation2003). However, in these studies probes with a 2,000-kDa cutoff or a membrane length of 30 mm had been used. Both characteristics result in a higher recovery as compared to probes with a 100-kDa cutoff and a membrane length of 4 mm, as used in the present study.

Fluid recovery was determined with Dextran-70 and BSA as additives. The addition of these osmotic agents is believed to prevent fluid loss from the membrane into the tissue due to the high porosity of the membrane (Rosdahl et al. Citation1997, Trickler and Miller Citation2003). We used a commercially available PES membrane (CMA/20) and found that fluid recovery was not dependent on osmotic agents such as Dextran-70 or BSA.

To estimate the efficiency of microdialysis in vivo further, we studied the total protein concentration of the microdialysate. For this investigation, only microdialysates that were collected without BSA in the perfusate were included. The total protein concentration obtained was in good agreement with the total protein concentration of approximately 0.2 mg/mL that has been found in microdialysates from the brain (Maurer et al. Citation2003, Hillman et al. Citation2005). Moreover, we were able to collect protein continuously over 24 h. The higher total protein concentration in the first 3-h interval can be attributed to the initial burst when starting microdialysis. Sampling was started immediately after surgery, without equilibration. It takes some time until the concentration gradient in the surrounding tissue of the catheter has developed and a steady-state sampling takes place (Beneviste et al. 1989). The steady collection of protein during the remaining time showed that adsorption of matrix components or proteins on the outside of the membrane or biofouling did not affect sampling and that consistent collection of protein over a period of 24 h is possible.

We studied IL-6 concentration in microdialysates from a critical-size bone defect. The creation of the defect results in a cavity that is instantly filled by fracture hematoma. Neutrophils infiltrate the fracture hematoma and secrete IL-6, which can be detected with microdialysis. TGF-β1 was only detected after BSA had been added to the perfusate. The local concentration of TGF-β1 at the site of injury remained relatively constant over 24 h. It is mainly secreted by macrophages that infiltrate the hematoma after 48–96 h. Thus, a higher content of TGF-β1 might be obtained when prolonging the time of sample collection. Microdialysates of UVB-irradiated skin showed a similar distribution of IL-6 and TGF-β1. IL-6 concentration increased rapidly within the first 8–16 h and declined to baseline after 24 h, however, the TGF-β1 concentration increased with some delay after 24 h (Averbeck et al. Citation2006).

In conclusion, microdialysis could be established in a critical-size bone defect. Continuous sampling of proteins over 24 h could allow a detailed analysis of the composition of the fracture hematoma over time, to further characterize the initial inflammatory reaction to injury and the first stages of fracture healing. Further studies should apply this method to a greater number of proteins in a variety of injury models.

YF and SR designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. SR supervised the project. YF performed the animal surgery, in vivo microdialysis, and ELISA, and also analyzed the data. WG performed the in vitro experiment, analyzed these data, and assisted in animal surgery. UH performed ELISA. AD took part in the animal surgery and in in vivo microdialysis. LH and UH provided conceptual advice and edited the manuscript.

We thank Dr Jung, Dr Spekl, and their team at the Animal Care Unit of Dresden University Hospital for their cooperation in conducting the animal experiments. We also thank the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, grant no. SFB-TR67, subprojects B1, B2, B5, and B6 for financial support, and pfm Medical Titanium Gmbh, Nürnberg, Germany, for coating the plates with titanium.

No competing interests resulted from this funding.

- Averbeck M, Beilharz S, Bauer M, . In situ profiling and quantification of cytokines released during ultraviolet B-induced inflammation by combining dermal microdialysis and protein microarrays. Exp Dermatol 2006;15(6): 447-54.

- Bellander BM, Cantais E, Enblad P, . Consensus meeting on microdialysis in neurointensive care. Intensive Care Med 2004;30(12): 2166-9.

- Benveniste H, Hansen AJ, Ottosen NS. Determination of brain interstitial concentrations by microdialysis. J Neurochem 1989;52(6): 1741-50.

- Bøgehøj MF, Emmeluth C, Overgaard S. Microdialysis in the femoral head of the minipig and in a blood cloth of human blood. Acta Orthop 2011;82(2): 241-5.

- Cho TJ, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA. Differential temporal expression of members of the transforming growth factor beta superfamily during murine fracture healing. J Bone Miner Res 2002;17(3): 513-20.

- Claes L, Recknagel S, Ignatius A. Fracture healing under healthy and inflammatory conditions. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2012;8(3): 133-43.

- Clough GF. Microdialysis of large molecules. AAPS J 2005;7(3): E686-92.

- Cox G, Einhorn TA, Tzioupis C, Giannoudis PV. Bone-turnover markers in fracture healing. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2010;92(3): 329-34.

- Dabrosin C. Variability of vascular endothelial growth factor in normal human breast tissue in vivo during the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88(6): 2695-8.

- Dabrosin C, Chen J, Wang L, Thompson LU. Flaxseed inhibits metastasis and decreases extracellular vascular endothelial growth factor in human breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Lett 2002;185(1): 31-7.

- Gouwy M, Struyf S, Proost P, Van Damme J. Synergy in cytokine and chemokine networks amplifies the inflammatory response. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2005;16(6): 561-80.

- Helmy A, Carpenter KL, Skepper JN, . Microdialysis of cytokines: methodological considerations, scanning electron microscopy, and determination of relative recovery. J Neurotrauma 2009;26(4): 549-61.

- Hillman J, Aneman O, Anderson C, . A microdialysis technique for routine measurement of macromolecules in the injured human brain. Neurosurgery 2005;56(6): 1264-8; discussion 1268-70.

- Lefkowitz DL, Lefkowitz SS. Macrophage-neutrophil interaction: a paradigm for chronic inflammation revisited. Immunol Cell Biol 2001;79(5): 502-6.

- Licht P, Lösch A, Dittrich R, . Novel insights into human endometrial paracrinology and embryo-maternal communication by intrauterine microdialysis. Hum Reprod Update 1998;4(5): 532-8.

- Maurer MH, Berger C, Wolf M, . The proteome of human brain microdialysate. Proteome Sci 2003;1(1): 7.

- Nyan M, Miyahara T, Noritake K, . Molecular and tissue responses in the healing of rat calvarial defects after local application of simvastatin combined with alpha tricalcium phosphate. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2010;93(1): 65-73.

- Petersen LJ, Kristensen JK, Bülow J. Microdialysis of the interstitial water space in human skin in vivo: quantitative measurement of cutaneous glucose concentrations. J Invest Dermatol 1992;99(3): 357-60.

- Rosdahl H, Ungerstedt U, Jorfeldt L, Henriksson J. Interstitial glucose and lactate balance in human skeletal muscle and adipose tissue studied by microdialysis. J Physiol 1993;471(637-57

- Rosdahl H, Ungerstedt U, Henriksson J. Microdialysis in human skeletal muscle and adipose tissue at low flow rates is possible if dextran-70 is added to prevent loss of perfusion fluid. Acta Physiol Scand 1997;159(3): 261-2.

- Schutte RJ, Oshodi SA, Reichert WM. In vitro characterization of microdialysis sampling of macromolecules. Anal Chem 2004;76(20): 6058-63.

- Stolle LB, Plock N, Joukhadar C, . Pharmacokinetics of linezolid in bone tissue investigated by in vivo microdialysis. Scand J Infect Dis 2008;40(1): 24-9.

- Thorsen K, Kristoffersson AO, Lerner UH, Lorentzon RP. In situ microdialysis in bone tissue. Stimulation of prostaglandin E2 release by weight-bearing mechanical loading. J Clin Invest 1996;98(11): 2446-9.

- Trickler WJ, Miller DW. Use of osmotic agents in microdialysis studies to improve the recovery of macromolecules. J Pharm Sci 2003;92(7): 1419-27.

- Waelgaard L, Pharo A, Tønnessen TI, Mollnes TE. Microdialysis for monitoring inflammation: efficient recovery of cytokines and anaphylotoxins provided optimal catheter pore size and fluid velocity conditions. Scand J Immunol 2006;64(3): 345-52.