Abstract

Background and purpose There have been numerous reports of animal models of osteomyelitis. Very few of these have been prosthesis models that imitate human conditions. We have developed a new rat model of implant-related osteomyelitis that mimics human osteomyelitis, to investigate the pathology of infection after orthop edic implant surgery.

Methods 2 wild-type strains of Staphylococcus aureus, MN8 and UAMS-1, and their corresponding mutants that are unable to produce poly-N-acetyl glucosamine (PNAG) (ica::tet) were injected into the medullary canals of the femur and tibia at 3 different doses: 102, 103, and > 104 CFU/rat. We measured clinical signs, inflammatory markers, radiographic signs, histopathology, and bacteriology in the infected animals.

Results An inoculum of at least 104 cfu of either wild-type bacterial strain resulted in histological, bacteriological, and radiographic signs of osteomyelitis with loosening of the prosthesis. An inoculum of 103 CFU gave signs of osteomyelitis but the prosthesis remained in situ. Bacterial inocula of 102 cfu gave no signs of osteolysis.

Interpretation We have established a new knee prosthesis model that is suitable for reliable induction of experimental implant-associated osteomyelitis with the prosthesis in situ, using a small inoculum of S. aureus. At a dose of 103 CFU/rat, bacteria unable to produce PNAG (ica::tet) had only minor defects in their virulence.

Infections associated with in-dwelling orthopedic devices can be difficult to cure without removing the device, and they are quite expensive to manage (Darouiche Citation2004). Usual infection-control measures, laminair air flow, and use of systemic antimicrobial prophylaxis have not completely eliminated orthopedic implant-related infections (Darouiche Citation2003). Staphylococcus aureus is the predominant bacterium associated with infected metal implants (Eron Citation1985). There is an urgent need to explore other approaches to enhance diagnosis, prevention and treatment of infection, and osteomyelitis—for which appropriate animal models are extremely useful (Monzón et al. Citation2002). The aim of the present study was to establish an implant model of acute osteomyelitis associated with metallic implants without any promoters of infection other than the implant itself.

Materials and methods

S. aureus strains and bacterial challenge ()

We used the MN8 strain of S. aureus, originally obtained from a patient with toxic shock syndrome-1 (TSST-1), and the genetically related UAMS-1 strain of S. aureus, a primary isolate from a patient admitted to the Arkansas Children’s Hospital with an osteoarticular and soft-tissue infection and septic shock (Lucke et al. Citation2003, Cassat et al. Citation2006). UAMS-1 is a clinical isolate from osteomyelitis and is therefore clearly relevant to the model. Strain MN8 is closely related to UAMS-1 genetically: both belong to the EMRSA-16 group of S. aureus, which are characterized by an identical mutation in the alpha-toxin gene that results in loss of production of this factor. ica-deficient strains were used to evaluate the role of PNAG antigen, which is synthesized by proteins encoded at the ica locus (Cramton et al. 1999), to determine whether it is a dominant feature of implant-related infections caused by S. aureus. To date, 100% of over 100 clinical isolates from all sources tested have been found to express poly-N-acetyl glucosamine (PNAG), which contributes to this organism’s ability to make biofilms. Biofilms are thought to be a major component of the pathogenesis of implant-related infections. Thus, PNAG may be a virulence factor in implant infections and is a known target for immunotherapy and vaccination.

Table 1. Inoculum, ica:tet status, and strain

41 rats were infected with 2 wild-type strains of S. aureus MN8 or UAMS-1, both of which are ica-positive, using inoculating doses of bacteria of 105, 104, 103, or 102 CFU/rat (MN8: n = 23; UAMS-1: n = 18). There were at least 3 rats in each challenge group.

Viable counts were done on the different bacterial strains to determine the exact dose inoculated. Both strains were also tested using mutants with deleted ica genes (ica::tet), which are referred to as ica-negative strains, at an infecting dose of 103 CFU/rat with four rats in each group (Cramton et al. 1999, Beenken et al. Citation2004, Kropec et al. Citation2005). 5 rats were followed without being infected (the control group). The animal s were followed for 2–6 weeks and then killed.

Anesthesia

All rats were sedated with a subcutaneous injection of hypnorm/dormicum, 0.3 mL/100 g body weight, given preoperatively and reinjected every 15 min (0.15 mL/100 g). After the operation, a femoralis block of the operated extremity was placed below the inguinal ligament using 1% lidocain/0.5% bupivacain in 1 mL. The rats were killed with an intracardiac injection of 2 mL pentobarbital (200 mg/mL).

Surgery

We used 54 Sprague-Dawley male rats that were 7–9 weeks-old (Taconic Europe) and weighing about 300 g. The experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Denmark (reg. no. 2005/561-1049 from September 19, 2005).

The skin over the left knee was sterilized twice with alcohol. The fur was removed with a hair razor. The knee was opened with a parapatellar medial incision and the tendon with the patella was dislocated laterally. The articulating cartilage was osteotomized with bone scissors from the distal femur, with the proximal tibia including the menisci and cruciate ligaments protecting the collateral ligaments. A 2-mm-wide and a 10-mm-deep hole was bored with a hand drill into the femur and tibia to fit the joint components. The joint capsule and skin were closed with Ethibond 4-0 and Vicryl 5-0 after placement of the knee prosthesis (press-fit model) without bone cement.

Prosthesis

A rat-sized, non-constrained knee prosthesis was used () The femoral component was made from a metal alloy and the tibial component was milled from high-density polyethylene stock.

Infection process

The infection was initiated by direct injection of 10 µL of the appropriate S. aureus bacterial suspension into the medullary canals of the femur and tibia. The volume of the suspension fitted into the marrow hole. Afterwards the condylar prosthesis was inserted.

Radiographic evaluation

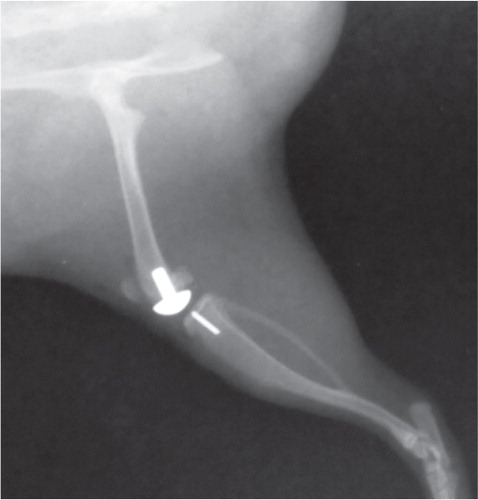

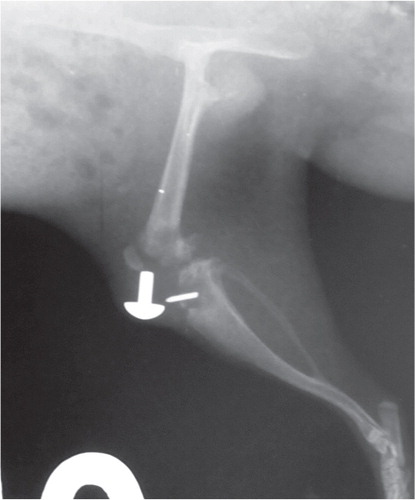

AP and lateral radiographs were taken on days 0 (OP), 7, 14, 21, and 42. To assess development and progression of bone infection, a modified scoring system was used (Schmidmaier et al. Citation2006). The following 6 parameters were scored: (I) periosteal reaction, (II) osteolysis, (III) soft-tissue swelling, (IV) deformity, (V) general impression or destruction, (VI) loosening of the prosthesis, and (VII) sequestrum formation. The score for each of the first 5 parameters used a scale of 0 to 4: 0 (absent), 1 (mild), 2 (moderate), 3 (severe). Parameter VI “loosening of the prosthesis” was judged as 0 (none), 1 (1 component), or 2 (both components), and parameter VII was judged as 0 (absent) or 1 (present). The maximum score that could be achieved was 18 ( and ).

Microbiological evaluation

The prosthesis components were explanted and rolled over non-selective media (5% Danish blood agar and chocolate agar plates (State Serum Institute, Copenhagen, Denmark). Isolated bacteria were identified as previously described (Højby and Frederiksen 2000). The same procedure was used for bone from the femurs and tibias and for the synovialis, which were rolled over Danish blood agar and chocolate agar in 3 directions and incubated at 37°C. Bacterial growth was judged as no growth, growth in the first streak (+), growth in the first 2 streaks (++), or growth in all 3 streaks (+++).

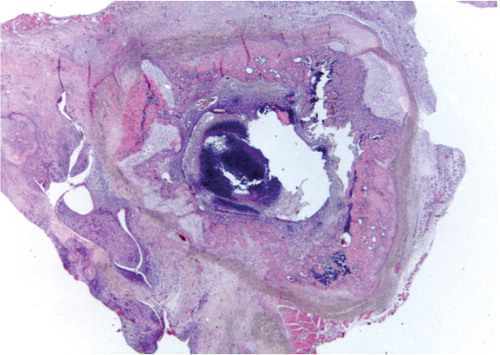

Bone and soft-tissue histology ()

After removal of the prosthesis, the remnants of the tibia, femur, and synovialis were fixed in 4% buffered paraformaldehyde and decalcified in 10% formic acid/EDTA for 7 days. Samples were embedded in paraffin and transverse sections of 5 μm, including the implantation site, were cut on a microtome. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For the first 30 rats, histological analysis of tissues from the blood, liver, and spleen was also carried out.

Semiquantitative scoring of all specimens was performed blind by pathologists who were not aware of the treatment groups (SSP and BMN).

For histological scoring of severity of inflammation, transverse sections of the tibia and femur (with the prosthesis removed) and tissue from the synovialis were investigated. Each of the 3 tissues (femur, tibia, and synovialis) was given a score ranging from 0 to 4, depending on the severity of inflammation. 0 meant no signs of inflammation, 1 was slight focal accumulation of inflammatory cells (neutrophils), 2 was a moderate but consistent inflammation in the transverse sections and/or moderate inflammation of the entire circumference around the cavity after prosthesis removal, 3 was the start of formation of an abscess in the cavity, and 4 was abscess formation and destruction of bone material with the synovialis completely infiltrated by neutrophils. The scores from the 3 separate tissues were added, giving a maximum score of 12.

Biochemical analysis

α-1 acid glycoprotein (AGP)—an acute-phase protein—was measured on days 0 (preoperatively), 7, 14, 21, and 42 (normal range: 0–130) (Matsumoto et al. Citation2007). Hemoglobin and leucocytes were also measured. There were no differences in the groups before and after the operation, irrespective of the bacterial strain and the infectious dose used.

Clinical evaluation

Body weight and temperature were determined, and well-being of the animal was estimated using food intake as a parameter . Macroscopic judgement of the knee was scored as described previously (Petty et al. Citation1988). Briefly , normal = 0, moderate swelling and edema = 0.5, swelling and abscess = 1.0, and abscess and illness of the animal = 1.5. If abscesses and/or fistulae were present, pus was aspirated and cultured on blood agar plates, and any bacteria were identified (Høiby 2000).

Statistics

All results are expressed as means. They were analyzed using the Kruskall-Wallis test for one-way analysis of variance. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS for Windows software version 12.2. All p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Radiography

No osteolysis or signs of inflammation were seen in any of the radiographs in the control group, including loosening of the prosthesis (). Radiographic changes in groups G1 and G5 (rats injected with 102 bacteria) indicated slight inflammation with little osteolysis and no loosening of the prosthesis. The modified scores (Schmidmaier et al. Citation2006) after 1 and 2 weeks were 2.9 and 3.6, respectively. Radiographs from most rats in groups G2 and G6 (injected with 103 bacteria, ica+) showed slight to moderate inflammation with osteolysis, a periosteal reaction, and soft-tissue swelling but the prosthesis remained in situ. The scores for G2 were 1.4 and 5.6 after 1 and 2 weeks, respectively, and for G6 they were 0 and 5.3 after 1 and 2 weeks, respectively. The rats infected with 103 CFU of the 2 different ica+ S. aureus strains MN8 and UAMS-1 (groups G3 and G7) had the same level of virulence as judged from the same scores of 7.4 and 5.5 after 2 weeks, respectively. The radiographic images of most rats in groups G4 and G8 (injected with > 104 ica+ S. aureus MN8 or UAMS-1, respectively) showed moderate to severe inflammation and most of the prostheses had loosened or were no longer in place (n = 12). For G4, mean scores after 1 and 2 weeks were 5.0 and 7.1, respectively, and for G8 mean scores of 7.2 and 7.8 were measured after 1 and 2 weeks ().

Table 2. Radiographic scores

Microbiology

No bacteria were cultured from the control group; thus, the prostheses were sterile. In G1 and G5 inoculated (with 102 CFU S. aureus), only 2 of 6 cultures obtained from the knees yielded a few colonies of S. aureus and these were seen only with the UAMS-1 strain. In G2 (wild-type strain MN8, 103 CFU) 8 of 12 implant cultures had a moderate number of colonies (++) and in G6 (wild-type strain UAMS-1, 103 CFU), all 6 cultures were positive (++). In G3 (ica- S. aureus MN8, 103 CFU), 3 of 4 cultures were positive at the ++ level. In G7 (ica- S. aureus UAMS-1, 103 CFU), all 4 cultures yielded colonies at the ++ level. In G4 and G8 (wild-type MN8 and wild-type UAMS-1, > 104 CFU), all cultures were positive for S. aureus at the +++ level. No bacteria could be cultured from spleen, liver, or blood.

Histopathology

The histopathology was consistent with the radiographic findings. No signs of inflammation were found in the control group. No histological signs of inflammation or bacteria were found in the liver, spleen, or blood in any of the groups. In the 2 groups that were given an inoculum of 102 (G1 and G5), all histological sections showed minor bone inflammation around the prosthesis with little bone destruction. In G2 and G6 (wild-type MN8 and wild-type UAMS-1 strains), the histopathology sections showed typical signs of bone inflammation (osteomyelitis) such as destruction of cortical and cancellous bone (osteolysis) and new bone formation. In G3 and G7 (the S. aureus ica-groups) the same findings were obtained but with less osteolysis. In G4 and G8 (wild-type MN8 and wild-type UAMS-1, > 104 CFU), there were massive signs of bone infection with destruction and abscess formation. 4 rats were killed or died preoperatively because of aspiration (). The 2 groups infected with more than 104 CFU were treated as 1 group for further analysis.

Table 3. Histopathology scores

Biochemistry and blood leukocyte counts

In the control group, the preoperative AGP levels were < 200 µg/mL. In G2 (wild-type MN8, 103 CFU), the AGP increased from a mean of 170 µg/mL to 542 µg/mL after 2 weeks, and then decreased to a mean of 424 after 4 weeks. In G6 (wild-type UAMS-1, 103 CFU), the AGP increased from a mean of 168 to 218 after 2 weeks. The rats cleared the infection after 2 weeks. Hemoglobin and leucocyte levels were not statistically significantly different from those in the control group, and the biochemistry parameters after 2 weeks and the leukocyte counts and hemoglobin levels were similar. Only the AGP parameter was relevant for measurement of inflammation.

Clinical results

There was no statistically significant difference in mean weight loss between the control group and the G1 to G3 (CFU ≤ 103 and G5 to G7 rats. However, the weight loss in G4 and G8 rats given the highest dose (> 104 CFU) was higher than in the control group. There was no soft-tissue swelling around the knee in the groups given 102 CFU (G1 and G5). Body temperature was similar in the different groups.

Discussion

Various experimental animal models of osteomyelitis have been developed since 1884 when Rodet and Lexer (Rodet Citation1885, Lexer Citation1894) demonstrated that osteomyelitis similar to that seen in humans could be created experimentally by injection of staphylococci to produce bone abscesses. Mader (Citation1985) and Norden (Citation1988), together with several other authors, demonstrated that osteomyelitis could be induced in an implant model by injection of bacteria into the tibia and femur cavities using either rats or rabbits (Mader Citation1985, Rissing Citation1990, An et al. Citation2006). Osteomyelitis studies related to orthopedic implant and prosthetic joint infection have been conducted using various animals such as rats (Zak et al. Citation1982, Rissing et al. Citation1985), rabbits (Nelson et al. Citation1990), dogs (Fokushima et al. Citation2005), and guinea pigs (Ofluoglu et al. Citation2007). The in vivo animal models of osteomyelitis have certain advantages, which have provided us with a clearer understanding of the osteomyelitis process and treatments. The limitations of the models were mostly due to differences in the immune systems of the animals, the non-physiological way the bacteria were inoculated into the animals, the short observation periods, and the high bacterial doses used (Mader Citation1985). Rats are the second most widely used animal for these studies, which is why we also used them. In addition, it is simple to evaluate the histological and microbiological bone processes in rats. Development of the surgical procedure and use of loop-glasses and a specially designed small non-constrained knee prosthesis allows evaluation of the osteomyelitis process in spite of the small size of the animal.

In most osteomyelitis models, lesions are induced by sclerosing agents, arachidonic acid, and foreign bodies containing bacteria to facilitate bone infection. Nelson et al. (Citation1990) and Fukushima et al. (2005) did not use sclerosing agents and foreign bodies in their rat osteomyelitis models. They infected the animals with a combination of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and S. aureus. Fukushima et al. (2005) examined the relationship between the inoculating dose of bacteria and the progression of osteomyelitis, and found that development of significant histological and radiographic signs of osteomyelitis required inocula of at least 6 × 103 CFU. Other authors have used foreign-body implants such as stainless steel pins and K-wires implanted into the bone marrow together with the bacteria to study the osteomyelitis process (Hudetz et al. Citation2008, Li et al. Citation2008).

In our rat model the foreign body was implanted as a knee prosthesis, to mimic the human condition in which the osteomyelitis process is initiated in the bone marrow around the prosthesis. Osteomyelitis was seen after 1 week; it was localized to the primary infected area without spreading to the liver, spleen, or blood. We found that inoculation of at least 103 CFU of 2 wild-type S. aureus isolates resulted in significant histological, bacteriological, and radiographic signs of osteomyelitis with loosening of the prostheses. Smeltzer et al. (Citation1997) found that development of radiographic and histologic signs of osteomyelitis required inocula of at least 104 CFU. They used the same strain as we used (UAMS-1). We also found that the prosthesis remained in situ with an inoculum of 103 CFU, but the prosthesis was expelled after inoculation with > 104 CFU (for either S. aureus strain). For both MN8 and UAMS-1, 103 CFU was the optimal inoculum for study of the osteomyelitis process around the prostheses.

The ica gene is a major operon for expression of a potential virulence factor, a polysaccharide involved in staphylococcal biofilm formation (PNAG). However, the role of biofilms in staphylococcal bone infection is still unclear (Knobben et al. Citation2007), and they may not require the PNAG polysaccharide for formation. Both of the ica-strains gave rise to osteomyelitis that was no different to that achieved with the wild-type strains at the same size of inoculum ( ). Hudetz et al. (Citation2008) found that the presence of ica genes had a strong effect on biofilm formation in vitro and a weak effect in vivo.

Overall, it appears that S. aureus causes persistent infection in a knee prosthesis implanted into rats, requiring a small number of bacteria. The tissue pathology and infection were independent of the presence of the ica genes and PNAG-dependent biofilm formation. We have also shown that after 2 weeks, the rats can clear the inflammation with doses between 103 and 105, indicating that it is not possible to study the course of inflammation for longer time. The immune system of the rat is quite different from the human immune system, which may explain their ability to clear the infection after injection of such relatively high doses. Even so, our study shows that a dose of 103 CFU of S. aureus would be a suitable experimental condition with which to study active and passive immunization against S. aureus in the same knee prosthesis model.

NHS: planning, surgery on the animals (with prostheses), and writing. NVJ: surgery on the animals (with prostheses), organization of data in tables, and planning of surgery. BMN: conducted the pathology and histological scoring analysis. ALJ: designed the analysis and testing to generate the biochemical data. JK: helped with veterinary problems, took care of the animals, and obtained clinical data on the animals. SSP: participated in generating the pathology and histological scoring data, along with the histopathological micrographs. GP: provided the bacterial strains, helped with immunological problems, edited the manuscript. HKJ: generated all of the microbiological data and scored inflammation.

We thank Prof. Mark Smeltzer for sending the UAMS-1 strains of S. aureus, Ulla Johansen for technical assistance, and Prof. Lars Dahlin for valuable comments on the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- An YH, Kang QK, Arciola CR. Animal models of osteomyelitis. Review. Int J Artificial Organs. 2006; 29 (4): 407-20.

- Beenken KE, Dunman PM, McAleese F, . Global gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. J Bacteriol 2004; 186 (14): 4665-84.

- Cassat J, Dunman PM, Smeltzer MS, . Transcriptional profiling of Staphyloccus aureus clinical isolate and its isogenic agr and sar-A mutants reveals global differences in comparison to the laboratory strain RN6390. Microbiology 2006; 152: 3075-90.

- Cramton SE, Ulrich M, Götz F, . Anaerobic Conditions Induce Expression of Polysaccharide Intercellular Adhesin in Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Infect Immun 2001; 69 (6): 4079-85.

- Darouiche RO. Antimicrobial approaches for preventing infections associated with surgical implants. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 36: 1284-9.

- Darouiche RO. Treatment of infections associated with surgical implants. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 1422-9.

- Eron LJ. Prevention of infection following orthopaedic surgery. Antibiot Chemother 1985; 33: 140-64.

- Fokushima N, Yokoyama K, Sasahara T, . Establishment of rat model of acute staphylococcal osteomyelitis: relationship between inoculation dose and development of osteomyelitis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg incl Arthroscopy and Sports Med 2005; 125 (3): 169-76.

- Hudetz D, Hudetz SU, Harris LG, . Week effect of metal type and ica genes on staphylococcal infection of titanium and stainless steel implants. Clin Microbiol Infect 2008; 14: 1135-45.

- Høiby N, Frederiksen B. Microbiology of cystic fibrosis. In: Cystic Fibrosis, 2nd edition (eds Hodson ME,Geddes D M). London: Arnold: 2000:83-107.

- Knobben BA, van der Mai HC, van Horn JR, . Transfer of bacteria between biomaterials surfaces in the operating room – an experimental study. J Biomed Mater Res A 2007; 80: 790-9.

- Kropec A, Maira-Litran T, Jefferson KK, . Poly-N-acetylglucosamine production in Staphylococcus aureus is essential for virulence in murine models of systemic infection. Infect Immun 2005; 73 (10): 6868-76.

- Lexer E. Zur experimentellen erzeugung osteomyelitischer herde. Arch Klin Chir 1894; 48: 181-200.

- Li D, Gromow K, Søballe K, et al. quantitative mouse model of implant- associated osteomyelitis and the kinetics of microbial growth, osteolysis and humoral immunity. J Orthop Research 2008; 26: 96-105.

- Lucke M, Schmidmaier G, Wildemann B, . A new model of implant-related Osteomyelitis in rats. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2003; 67 (1): 593-602.

- Mader JT. Animal models of osteomyelitis. Am J Med 1985; 78: 213-7.

- Matsumoto K, Nishi K, Kadowaki D, . Alpha1-acid glycoprotein suppresses Rat acute inflammatory paw oedema through the inhibition of neutrophils activa-Tion and prostaglandin E2 generation. Biol Pharm Bull 2007; 30 (7): 1226-30.

- Monzón M, Garcia-Alvarez F, Laclériga A, Amorena B. Evaluation of four experimental osteomyelitis infection models by using precolonized implants and bacterial suspensions. Acta Orthop Scand 2002; 73 (1): 11-9.

- Nelson DR, Buxton TB, Luu QN, Rissing JP. The promotional effect of bonewax on experimental Staphylococcus aureus osteomyelitis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1990; 99: 977-80.

- Norden CW. Lessons learned from animal model of osteomyelitis. Rev Infect Dis 1988; 10: 103-10.

- Ofluoglu EA, Zileli M, Aydin D, . Implant-related infection model of rat spine. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2007; 127: 391-6.

- Petty W, Spanner S, Shuster J. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1988; 70: 536-9.

- Rissing JP. Animal models of osteomyelitis; knowledge, hypothesis, and speculation. Infect. Dis Clin North Am 1990; 4: 377-90.

- Rissing JP, Buxton TB, Weinstein RS, . Model of experimental chronic osteomyelitis in rats. Infect. Imun 1985; 47: 581-6.

- Rodet A. Physiologie pathologique – etude expérimentale sur l´ostéomyelite infectieuse. C R Acad Sci 1885; 99: 569-71.

- Schmidmaier G, Luke M, Wildermann B, . Prophylaxes and treatment of implant-related infections by antibiotic-coated implants; a review Int J Care Injury. 2006; 37: 105-12.

- Smeltzer MS, Thomas JR, Hickmon SG, . Characterization of rabbit model of staphylococcal osteomyelitis. J Orthop Res 1997; 15: 414-21.

- Zak O, Zak F, Rich R, . Experimental staphylococcal osteomyelitis in rats; therapy with rifampin and cloxacillin alone or in combination. In: Perty P, Grassi GG (eds) Current chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Am Soc for Microbiology, Washington DC 1982: 973-4.