Abstract

Background and purpose Indications for acromioplasty are based on clinical symptoms and are generally supported by typical changes in acromial morphology on standard radiographs. We evaluated 5 commonly used radiographic parameters of acromial morphology and assessed the association between different radiographic characteristics on the one hand and subacromial impingement or rotator cuff tears on the other.

Patients and methods We measured acromial type (Bigliani), acromial slope (AS), acromial tilt (AT), lateral acromial angle (LAA), and acromion index (AI) on standard radiographs from 50 patients with full-thickness supraspinatus tendon tears, 50 patients with subacromial impingement, and 50 controls without subacromial pathology.

Results The acromial type according to Bigliani was not associated with any particular cuff lesion. A statistically significant difference between controls and impingement patients was found for AS. AT of controls was significantly smaller than that of impingement patients and cuff-tear patients. LAA of cuff-tear patients differed significantly from that of controls and impingement patients, but LAA of controls was not significantly different from that of impingement patients. Differences between impingement patients and cuff-tear patients were also significant. AI of controls was significantly lower than of impingement patients and of cuff-tear patients. A good correlation was found between acromial type and AS.

Interpretation A low lateral acromial angle and a large lateral extension of the acromion were associated with a higher prevalence of impingement and rotator cuff tears. An extremely hooked anterior acromion with a slope of more than 43° and an LAA of less than 70° only occurred in patients with rotator cuff tears.

Subacromial impingement and rotator cuff tears are common and often require surgical treatment. The underlying causes are still poorly understood. Whether intrinsic degenerative changes in the tendons or extrinsic mechanical compression by the acromion are responsible for rotator cuff tears is still a matter of debate. In 1931, Codman originally described degenerative changes of the tendons that initiate rotator cuff tears (Codman and Akerson Citation1931). On the other hand, Armstrong suggested in Citation1949 that compression of the bursa and rotator cuff tendons under the acromion causes the supraspinatus syndrome (Armstrong Citation1949). Later on, Neer (Citation1983) stated that 95% of cuff tears are caused by mechanical impingement and reported successful treatment by anterior acromioplasty (Neer Citation1972). Since then, both theories have been supported in numerous publications (for example, Bigliani et al. Citation1991, Nicholson et al. Citation1996, Shah et al. Citation2001, Gill et al. Citation2002). However, acromioplasty is still the standard operative treatment for impingement lesions, and there has been a substantial increase in its incidence in the United States (Vitale et al. Citation2010).

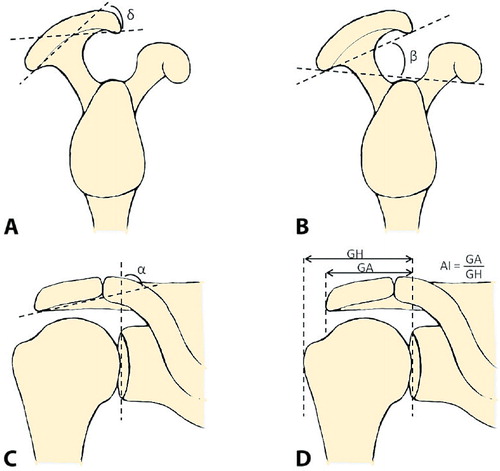

Although the indication for acromioplasty is based on clinical evaluation of the patient, it is generally supported by typical changes in acromial morphology on standard radiographs (Neer Citation1972, Aoki et al. Citation1986, Bigliani et al. Citation1986, Zuckerman et al. Citation1992, Banas et al. Citation1995, Toivonen et al. Citation1995, Tetreault et al. Citation2004). The most common classification is the one by Bigliani et al. (Citation1986) describing a flat (type-I), curved (type-II), or hooked (type-III) acromion on outlet-view radiographs. In some studies, a type-III acromion has been found to be associated with a higher prevalence of rotator cuff tears (Bigliani et al. Citation1986, Citation1991, MacGillivray et al. Citation1998) whereas not all authors have found this (Ozaki et al. Citation1988, MacGillivray et al. Citation1998). Several attempts have been made to classify the acromial morphology. Bigliani et al. (Citation1986) and Kitay et al. (Citation1995) described the acromial slope (AS; ), and Kitay et al. (Citation1995) and Aoki et al. (Citation1986) described the acromial tilt (AT; ).

Other authors have focused on the lateral rather than the anterior extension of the acromion (Banas et al. Citation1995, Tetreault et al. Citation2004, Nyffeler et al. Citation2006). Banas et al. (Citation1995) described the frontal plane slope of the acromion on MRI and found a lower lateral acromial angle (LAA; ) in patients with rotator cuff disease. Nyffeler et al. (Citation2006) observed that the acromion of patients with a rotator cuff tear appeared to have a more lateral extension than that of patients with an intact cuff, and described the acromion index (AI; ).

Despite the numerous studies that have been carried out in an attempt to support or refute Neer’s original theory of extrinsic mechanical impingement as the primary etiology of rotator cuff disease, the role of the acromion is still unclear. We therefore evaluated 5 commonly used parameters of acromial morphology (acromial type, acromial slope, acromial tilt, lateral acromial angle, and acromion index) and their relationship to subacromial impingement and rotator cuff tears.

Patients and methods

Patients and controls

Surgical reports and corresponding preoperative radiographs of 563 patients who underwent shoulder arthroscopy for impingement symptoms from 2004 through 2009 at the Department of Orthopedics, Münster University Hospital, were retrospectively reviewed. In 113 patients with documented full-thickness supraspinatus tendon tears (the cuff-tear group (group 3)) standard true anteroposterior radiographs and standard outlet-view preoperative radiographs of sufficient quality were available. 50 of these 113 patients were randomly selected.

In 167 patients with subacromial impingement syndrome and documented intact rotator cuff, preoperative standard radiographs were of sufficient quality. 50 of these patients were randomly selected (the impingement group (group 2)).

50 patients who had presented from 2010 to 2012 with a previously healthy “bruised shoulder” to the trauma center of the Department of Trauma and Orthopedic Surgery, Cologne-Merheim Medical Center, and who had sufficient radiographs served as controls (the control group (group 1)). All patients with previous shoulder surgery, fractures, infections, tumors, or symptoms of impingement or rotator cuff tears were excluded. Control subjects only had symptoms unrelated to impingement tests according to Neer and Hawkins, and did not have any weakness in rotator cuff tests (starter test, Jobe test, internal and external rotation, belly-press test, and lift-off test). For the true anteroposterior radiograph, the patient was positioned with the scapula adjacent to the X-ray cassette. The arm was held in neutral position with the elbow extended and the thumb aiming anterior. Beam alignment was 20° caudal. For the outlet-view radiograph, the affected shoulder with the arm hanging was turned 30° away from the X-ray stand. Beam alignment was tangential to the scapula, 10–15° caudo-cranial.

Acromial type

The acromial type was classified according to Bigliani et al. (Citation1986). Type I represents a flat, type II a curved, and type III a hooked undersurface of the acromion on outlet-view radiographs.

Acromial slope ()

The acromial slope (AS) was measured on outlet-view radiographs according to Bigliani et al. (Citation1986) and Kitay et al. (Citation1995). One line was drawn connecting the most anterior point of the inferior acromion and the midway point on the inferior acromion. Another line was drawn connecting the most posterior point of the inferior acromion with the same midway point. The angle (δ) formed by these 2 lines represented the AS.

Acromial tilt ()

The acromial tilt (AT) was measured on outlet-view radiographs as described by Kitay et al. (Citation1995) and Aoki et al. (Citation1986). One line was drawn connecting the most posterior point of the inferior acromion to the most anterior point of the inferior acromion. Another line was drawn connecting the same most posterior point of the inferior acromion to the inferior tip of the coracoid process. The resulting angle (β) represented the AT.

Lateral acromial angle ()

The lateral acromial angle (LAA) was measured on true anteroposterior radiographs according to Banas et al. (Citation1995). One line was drawn along the superior- and inferior-most lateral points of the glenoid and represented the glenoid surface. Another line was drawn parallel to the acromion undersurface. The angle between these 2 lines (a) represented the LAA.

Acromion index ()

The acromion index (AI) was measured on true anteroposterior radiographs according to Nyffeler et al. (Citation2006). The distance from the glenoid plane to the acromion (GA) was divided by the distance from the glenoid plane to the lateral aspect of the humeral head (GH). The larger the extension of the acromion, the higher the AI.

Evaluation of radiographs

All radiographs taken before 2009 were digitized and measurements were made with the open-source Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine (DICOM) Viewer OsiriX. All radiographs since 2009 were digitally acquired and measured on a DICOM viewer with digital angle measurement. The appropriateness of the radiographs was evaluated by 2 independent examiners. Only when both examiners were convinced about the quality of the radiographs were they used for the study. Measurements were made according to agreement by both examiners who were unaware of the underlying clinical symptoms.

Statistics

Acromion type according to Bigliani, AS, AT, LAA, and AI were tested for correlation to each other and to sex, side, and age using the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC), which was graded as excellent (0.81–1.00), good (0.61–0.80), moderate (0.41–0.60), fair (0.21–0.40), or poor (0.00–0.20). The means for age, AS, AT, LAA, and AI from each group were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. The significance level was set to p < 0.05. Calculations were done using SPSS software version 13.0.

The study was reviewed and approved by the local ethics committee.

Results

Patient demographics ( and )

The mean age of the control subjects (group 1) was 48 years, that of the impingement patients (group 2) was 49 years, and that of the cuff-tear patients (group 3) was 60 years. The overall distribution of the acromion shape according to Bigliani et al. (Citation1986) was type I in 25% of individuals, type II in 61%, and type III in 14%.

Table 1. Frequencies and (percentages)

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

Rotator cuff tears (group 3) mostly affected the left shoulder. Controls (group 1) and impingement cases (group 2) mostly had the the right shoulder affected.

Acromial type ()

In all 3 groups, more than 50% of acromia were graded as type-II. Only 2% of the controls had a type-III acromion, in contrast to 20% of impingement and cuff-tear patients.

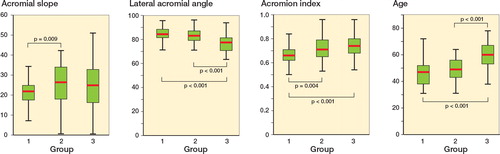

Acromial slope (, )

The mean AS of the controls (21°) was smaller than the slope of the impingement (25°) and cuff-tear patients (25°). There was a statistically significant difference between groups 1 and 2 (p = 0.009) but not between group 1 and group 3 (p = 0.1) or group 2 and group 3 (p = 0.7). The mean AS for acromion type I was 12°, for type II it was 26°, and for type III it was 37°. A slope of more than 43° occurred only in 4 patients with rotator cuff tears. The average age of these patients was 55 (47–59) years, whereas the other 46 patients with cuff tears and a slope of less than 43° had an average age of 61 (38–78) years. The difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.2).

Acromial tilt ()

The mean AT of the controls would be expected to be higher than in pathological shoulders, but the mean AT of group 1 (29°) was significantly smaller than that of group 2 (33°; p < 0.001) and that of group 3 (34°; p < 0.001). Groups 2 and 3 were not significantly different in this respect (p = 0.5).

Lateral acromial angle (, )

The mean LAA of group 1 (84°) was not significantly different to that of group 2 (83°; p = 0.3) but it was significantly different to that of group 3 (77°; p < 0.001). The differences between groups 2 and 3 were also significant (p < 0.001). An LAA of < 70° only occurred in patients with rotator cuff tears (n = 11). The average age of these patients was 59 (47–78) years and it was similar to the average age of 60 (38–76) years for the remaining 39 patients with cuff tears and an LAA of > 70° (p = 0.6).

Acromion index (, )

The mean AI of the controls (0.67) was lower than that of group 2 (0.73; p = 0.004) and of group 3 (0.75; p < 0.001). The difference between group 2 and 3 did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.2).

Patient age (, )

The mean ages of group 1 (48 years) and group 2 (49 years) were similar (p = 0.107), but those of groups 1 and 3 (60 years) (p < 0.001) and groups 2 and 3 (p < 0.001) were significantly different.

Correlations ()

The only good correlation found was between acromial type (Bigliani) and AS. A moderate correlation was found between LAA and AI. A fair correlation was found between age and LAA, age and AI, acromial type and AT, and LAA and AT. No correlations were found between sex and the different parameters tested.

Table 3. Correlations

Discussion

Only 2% of the controls had a type-III acromion according to Bigliani et al. (Citation1986), as compared to 20% in the impingement and cuff-tear patients. Acromion of type III was common in both impingement and rotator cuff-tear groups without any significant differences. Like other authors, we did not find any significant correlation between acromion type and age (Banas et al. Citation1995, Vahakari et al. Citation2010). Our results regarding the acromial slope (Bigliani et al. Citation1986, Kitay et al. Citation1995, Tuite et al. Citation1995) are somewhat controversial. Whereas the controls generally had a smaller slope angle than impingement patients, they did not differ significantly in this respect from patients with cuff tears (). The slope angle did not correlate with age but showed a good correlation with the Bigliani classification (). The average AS being related to acromial type is in accordance with the results of Toivonen et al. (Citation1995). Tuite et al. (Citation1995) found a mean AS angle of 24° in patients with an intact rotator cuff and 29° in patients with a full-thickness tear, and they concluded that the angle is useful for identification of patients with a greater likelihood of having a rotator cuff tear. In the present study, a slope of more than 43° only occurred in 4 patients with rotator cuff tears. The average age of these patients was lower (54.5 years) than that of the other 46 patients with cuff tears (60.7 years) and a slope of less than 43°. Thus, whereas the AS and the Bigliani classification are not useful for prediction of the likelihood of a cuff tear in most shoulders, the rare occurrence of a very high slope angle corresponding to an extremely hooked acromion appears to give a hint of rotator cuff disease even in younger patients.

Because the acromial tilt describes the relationship between the anterior acromion and the coracoid process, we expected a lower tilt angle to be associated with a higher incidence of rotator cuff tears as reported by others (Aoki et al. Citation1986, Zuckerman et al. Citation1992, Kitay et al. Citation1995, Prato et al. Citation1998). Surprisingly, in our patients the tilt angle in the controls was lower than in pathological shoulders (). The reason for this is unclear. A possible explanation might be variability in the outlet-view radiographs (Stehle et al. Citation2007).

Concerning the lateral acromial angle (LAA), we confirmed the results of Banas et al. (Citation1995) who described a statistically significant correlation between the LAA and rotator cuff disease determined by MRI. In a previous study, we evaluated the use of the LAA in conventional radiographs and described good interobserver reliability for MRI, and true anteroposterior radiographs (under review). Tetreault et al. (Citation2004) also found a smaller angle between the acromion and the glenoid surface. They postulated that a smaller angle may reduce the volume available for the content of the shoulder joint and ultimately impose detrimental pressure on the rotator cuff. In our study and in that by Banas, an extremely low LAA of less than 70° only occurred in cuff tears. They found that of the 8 patients with complete tears and LAA of less than 70°, the average age was 54 years—whereas the average age of the remaining 18 patients with cuff tears and LAA greater than 70° was 70 years. In the present study, both groups were of very similar average age (59 and 60 years). The LAA showed fair correlation with age in our study (), and there was moderate correlation (PCC = 0.46) in the original study by Banas et al. (Citation1995). Like these authors, we did not find a significant correlation between LAA and acromion type according to Bigliani (). In our opinion, the LAA can help differentiate on the one hand between controls and rotator cuff tears and on the other hand between impingement and rotator cuff tears.

Regarding the acromion index (AI), the findings by Nyffeler et al. (Citation2006) and Torrens et al. (Citation2007) are supported by our study. We found a significantly lower AI in controls than in impingement and cuff-tear patients. We did not find a significant difference between impingement patients and cuff-tear patients ( and ). The average AI in our study was similar to that in the study by Nyffeler et al. (Citation2006), which speaks for the consistency of the measurement technique. Contrary to our results and those of Torrens et al. (Citation2007) and Nyffeler et al. (Citation2006), Hamid et al. (Citation2012) did find similar AI values between subjects with full-thickness rotator cuff tears and subjects with no history of rotator cuff disease. As mentioned by Hamid et al., the contrary findings might in part be explained by subtle differences in the methods of radiographic assessment. Taking into account the similarity of the results by us, by Nyffeler et al. and by Torrens et al., we are convinced that the AI can help differentiate between healthy shoulders and shoulders with subacromial pathology—but perhaps not between impingement and cuff tears. This latter differentiation appears to be possible using the LAA.

In the present study, the patients with subacromial impingement were the same age as the controls, but the patients with rotator cuff tears were generally older. This finding was to be expected as the incidence of rotator cuff tears increases with age (Banas et al. Citation1995, Yamaguchi et al. Citation2006). Regarding the different classifications and their correlation with age, we only found fair correlations for LAA and AI. This supports the findings by Vahakari et al. (Citation2010) who evaluated routine outlet-view radiographs in different age groups and did not find any statistically significant differences.

The present study had some limitations. Suboptimal radiographs may influence the different measurements (Prato et al. Citation1998, Stehle et al. Citation2007). This is particularly true because the radiographs of controls were taken in a different institution than the radiographs of impingement and cuff-tear patients. Although 2 experienced orthopedic surgeons who were blinded regarding the diagnoses evaluated the radiographs, we did not test the reliability of our measurements. Whereas the controls and impingement patients were of comparable age, cuff-tear patients were older. As some radiographic parameters also correlate with age, this again might have caused bias. Because this correlation was at best fair, we still believe in the significance of our results. Patients presenting with a “bruised shoulder” at a trauma department served as controls. We excluded patients with fractures, tumors, previous surgeries, infection, impingement, or cuff tears. The latter was only excluded by clinical examination, but we did not check for asymptomatic rotator cuff tears (e.g. by MRI or ultrasound). Thus, we might have accidentally included patients with asymptomatic cuff tears in our control group.

In summary, low lateral acromial angle and a large lateral extension of the acromion are associated with a higher prevalence of impingement and rotator cuff tears. In this study, an extremely hooked anterior acromion with a slope of more than 43° and an LAA of less than 70° only occurred in patients with rotator cuff tears. Our findings do not fully explain the cause of rotator cuff tears, but they might shift the focus from the anterior to the lateral extension/angulation of the acromion when diagnosing and treating subacromial pathologies.

The study was designed by MB and DL. Patients and control subjects were collected, examined, and the documents reviewed by MB, DL, ND, MBAN,and BB. Radiographic measurements were made by MB, DL, and MBAN. MB, DL, CS, and ND wrote the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

Notes

- Aoki M, Ishii S, Usui M. The slope of the acromion and rotator cuff impingement. Orthop Trans 1986; 10: 228.

- Armstrong JR. Excision of the acromion in treatment of the supraspinatus syndrome; report of 95 excisions. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1949; 31 (3): 436-42.

- Banas MP, Miller RJ, Totterman S. Relationship between the lateral acromion angle and rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1995; 4 (6): 454-61.

- Bigliani LU, Morrison DS, April EW. The morphology of the acromion and its relationship to rotator cuff tears. Orthop Trans 1986; 10: 228.

- Bigliani LU, Ticker JB, Flatow EL, Soslowsky LJ, Mow VC. The relationship of acromial architecture to rotator cuff disease. Clin Sports Med 1991; 10 (4): 823-38.

- Codman EA, Akerson IB. The pathology associated with rupture of the supraspinatus tendon. Ann Surg 1931; 93 (1): 348-59.

- Gill TJ, McIrvin E, Kocher MS, Homa K, Mair SD, Hawkins RJ. The relative importance of acromial morphology and age with respect to rotator cuff pathology. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11 (4): 327-30.

- Hamid N, Omid R, Yamaguchi K, Steger-May K, Stobbs G, Keener JD. Relationship of radiographic acromial characteristics and rotator cuff disease: a prospective investigation of clinical, radiographic, and sonographic findings. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21 (10): 1289-98.

- Kitay GS, Iannotti JP, Williams GR, Haygood T, Kneeland BJ, Berlin J. Roentgenographic assessment of acromial morphologic condition in rotator cuff impingement syndrome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1995; 4 (6): 441-8.

- MacGillivray JD, Fealy S, Potter HG, O’Brien SJ. Multiplanar analysis of acromion morphology. Am J Sports Med 1998; 26 (6): 836-40.

- Neer CS, 2nd. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1972; 54 (1): 41-50.

- Neer CS, 2nd. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop 1983; (173): 70-7.

- Nicholson GP, Goodman DA, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. The acromion: morphologic condition and age-related changes. A study of 420 scapulas. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1996; 5 (1): 1-11.

- Nyffeler RW, Werner CM, Sukthankar A, Schmid MR, Gerber C. Association of a large lateral extension of the acromion with rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006; 88 (4): 800-5.

- Ozaki J, Fujimoto S, Nakagawa Y, Masuhara K, Tamai S. Tears of the rotator cuff of the shoulder associated with pathological changes in the acromion. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1988; 70 (8): 1224-30.

- Prato N, Peloso D, Franconeri A, Tegaldo G, Ravera GB, Silvestri E, Derchi LE. The anterior tilt of the acromion: radiographic evaluation and correlation with shoulder diseases. Eur Radiol 1998; 8 (9): 1639-46.

- Shah NN, Bayliss NC, Malcolm A. Shape of the acromion: congenital or acquired--a macroscopic, radiographic, and microscopic study of acromion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2001; 10 (4): 309-16.

- Stehle J, Moore SM, Alaseirlis DA, Debski RE, McMahon PJ. Acromial morphology: effects of suboptimal radiographs. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16 (2): 135-42.

- Tetreault P, Krueger A, Zurakowski D, Gerber C. Glenoid version and rotator cuff tears. J Orthop Res 2004; 22 (1): 202-7.

- Toivonen DA, Tuite MJ, Orwin JF. Acromial structure and tears of the rotator cuff. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1995; 4 (5): 376-83.

- Torrens C, Lopez JM, Puente I, Caceres E. The influence of the acromial coverage index in rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16 (3): 347-51.

- Tuite MJ, Toivonen DA, Orwin JF, Wright DH. Acromial angle on radiographs of the shoulder: correlation with the impingement syndrome and rotator cuff tears. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1995; 165 (3): 609-13.

- Vahakari M, Leppilahti J, Hyvonen P, Ristiniemi J, Paivansalo M, Jalovaara P. Acromial shape in asymptomatic subjects: a study of 305 shoulders in different age groups. Acta Radiol 2010; 51 (2): 202-6.

- Vitale MA, Arons RR, Hurwitz S, Ahmad CS, Levine WN. The rising incidence of acromioplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2010; 92 (9): 1842-50.

- Yamaguchi K, Ditsios K, Middleton WD, Hildebolt CF, Galatz LM, Teefey SA. The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease. A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2006; 88 (8): 1699-704.

- Zuckerman JD, Kummer FJ, Cuomo F, Simon J, Rosenblum S, Katz N. The influence of coracoacromial arch anatomy on rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1992; 1 (1): 4-14.