Abstract

Background and purpose — Plain radiographs may fail to reveal an ankle fracture in children because of developmental and anatomical characteristics. In this systematic review and meta- analysis, we estimated the prevalence of occult fractures in children with acute ankle injuries and clinical suspicion of fracture, and assessed the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound (US) in the detection of occult fractures.

Methods — We searched the literature and included studies reporting the prevalence of occult fractures in children with acute ankle injuries and clinical suspicion of fracture. Proportion meta-analysis was performed to calculate the pooled prevalence of occult fractures. For each individual study exploring the US diagnostic accuracy, we calculated US operating characteristics.

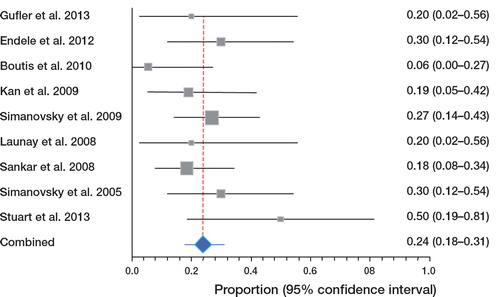

Results — 9 studies (involving 187 patients) using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (n = 5) or late radiographs (n = 4) as reference standard were included, 2 of which also assessed the diagnostic accuracy of US. Out of the 187 children, 41 were found to have an occult fracture. The pooled prevalence of occult fractures was 24% (95% CI: 18–31). The operating characteristics for detection of occult ankle fractures by US ranged in positive likelihood ratio (LR) from 9 to 20, and in negative LR from 0.04 to 0.08.

Interpretation — A substantial proportion of fractures may be overlooked on plain radiographs in children with acute ankle injuries and clinical suspicion of fracture. US appears to be a promising method for detection of ankle fractures in such children when plain radiographs are negative.

Acute ankle injuries (AAI) are common in patients of all ages and may constitute up to 12% of emergency department (ED) visits (Cockshott et al. Citation1983). They involve about 25% of all injuries of the musculoskeletal system (Pijnenburg et al. Citation2000). It has been estimated that approximately 1ankle injury per 10,000 people occurs every day (Vasukutty et al. Citation2011).

Of primary concern is whether patients with AAI have fractures. When there is clinical suspicion of fracture, clinicians have traditionally relied on the use of plain radiographs to exclude ankle fractures. However, interpretation of conventional radiographic imaging of childhood injuries is challenging, due to the developmental and anatomical characteristics of children (Marsh and Daigneault Citation2000). In children, plain radiographs may fail to reveal a fracture; accurate diagnosis can be complicated by endochondral ossification, additional areas of ossification, and open epiphyseal plates (Endele et al. Citation2012). This gives a risk of over- treatment of children without fracture and under-treatment of those with fracture, with medical (Ogden Citation1987), financial (Kan et al. Citation2009), and psychosocial (Loder et al. Citation1995) consequences.

Using different imaging methods such as late radiographs (Simanovsky et al. Citation2005, Citation2009, Sankar et al. Citation2008, Kan et al. Citation2009) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Stuart et al. Citation1998, Launay et al. Citation2008, Boutis et al. Citation2010, Endele et al. Citation2012, Gufler et al. Citation2013) as reference standard, numerous studies have looked for the presence of occult fractures in children with radiograph-negative AAI and clinical suspicion of fracture. Some authors have also assessed the accuracy of ultrasound (US) in the detection of occult ankle fractures, comparing it with late radiographs as reference standard (Simanovsky et al. Citation2005, Citation2009). To date, however, no systematic reviews or meta-analyses on this topic have appeared. We therefore undertook a systematic review and—where appropriate—a meta-analysis of the relevant literature to estimate the prevalence of occult fractures in children with AAI. The main questions addressed in this review were: “what is the prevalence and what is the clinical significance of occult fractures in children with radiograph-negative AAI and clinical suspicion of fracture?” We also wanted to assess the diagnostic accuracy of US in detection of occult fractures in such children.

Methods

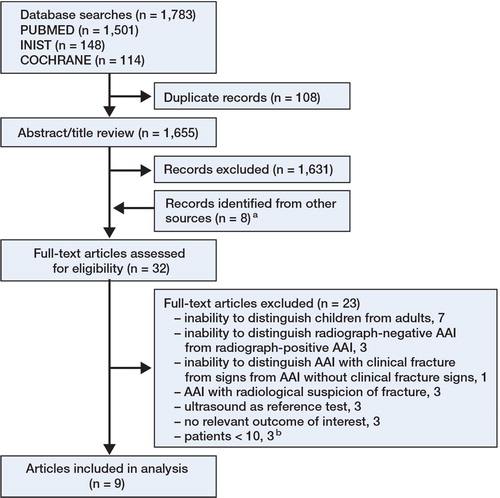

We conducted and reported this systematic review in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement (Moher et al. Citation2009).

Search strategy

In the literature search, we tried to identify all articles covering the prevalence of occult fractures in children with AAI and clinical signs of fracture. To identify eligible original articles, we searched the following electronic databases from inception to March 2013: MEDLINE via PUBMED, INIST (Scientific and Technical Information Institute) via article@inist, and the COCHRANE library. In each electronic database, various combinations of the following search terms were used: “ankle”, “injury”, “trauma”, “fracture”, “growth plate”, “physis”, “epiphysis”, “sprain”, “radiology”, “sonography”, “magnetic resonance imaging”, and “computed tomography”. The reference lists of potentially relevant articles were also screened for additional articles of interest. The detailed search strategy for MEDLINE via PUBMED is given in the Appendix (see Supplementary data).

Eligibility criteria

We applied explicit a priori inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies published before March 30, 2013 were eligible for inclusion if: (1) they reported data on the prevalence of occult fractures in children ≤ 18 years of age with radiograph-negative acute blunt ankle injury and clinical suspicion of fracture, (2) they used MRI or late radiographs as reference standard to confirm bone injuries in ≥ 80% of cases, and (3) they were written in English, French, Spanish, or German. Studies that included children with other suspected appendicular fractures or children with other clinical or radiographic characteristics were included if data pertaining to children with radiograph-negative AAI with clinical suspicion of fracture could be extracted from the study population. Studies that included adult and children populations were selected if they reported age-stratified analyses (so that the adult population could be excluded). Where necessary, we attempted to contact authors who published more than 1 study to establish whether they had reported results for overlapping patient populations. Because of the likelihood that small studies would have overestimated event outcome rates, studies involving less than 10 patients were excluded. Case reports, review articles, editorials, comments, and clinical guidelines were also excluded.

Study selection process

Study selection was carried out independently by 2 reviewers (AN and EN) in 2 rounds. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (AM).

Outcome measures and definitions

The primary outcome measures were the prevalence and clinical significance of occult ankle fractures. The secondary outcome measure was the diagnostic accuracy of US in the detection of occult fractures. The ankle was defined as the malleolar area and the midfoot area, both of which are commonly involved in twisting injuries. AAI was defined as any case of painful ankle with sudden onset, resulting from trauma. An occult ankle fracture was defined as a fracture not detected on plain radiographs immediately after ankle injury, but it was visible on late radiographs only after the healing process had begun (which may be as early as 7 days after injury) (Prosser et al. Citation2005), or on MRI as fracture lines. Fractures that carry excellent prognosis without treatment, except for maximizing patient comfort, were classified as insignificant. All other fractures were classified as significant, because they may destabilize the ankle, and they require closer clinical and radiographic follow-up (Boutis et al. Citation2001).

Data collection and quality assessment

Data extraction and quality assessment of the studies included were performed independently by 2 reviewers (AN and EN) using a standardized data collection form. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (AM). The following information was extracted from each study: first author, publication year, study design, clinical setting, participants (number, age), inclusion and exclusion criteria, reference standard, criteria for positivity of the reference standard, number of outcome events (fracture, other bone-related injuries), and number of patients in whom the outcome events were determined by reference standard. For each study exploring the diagnostic accuracy of US, we extracted the raw data regarding true and false positives and negatives. We adapted a quality assessment system for prevalence articles (Richardson et al. Citation1999). Each article was reviewed to determine whether: (1) study design was appropriate for obtaining prevalence estimate, (2) the sample was representative of the population of interest (age, condition, and clinical findings), (3) well- defined criteria for positivity of the reference standard were provided, and (4) outcomes of interest were adequately determined by the reference standard. We assessed these quality indicators separately; a total quality score was not calculated (Jüni et al. Citation1999).

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Prevalence was calculated by dividing the number of children with the target outcome by the number of children included in the study. A meta-analysis was performed when at least 3 studies provided data. A proportion meta-analysis was performed to calculate the pooled prevalence of occult fractures. Proportions were first transformed into a quantity based upon the Freeman-Tukey variant of the arcsine square root transformed proportion (Kendall et al. Citation1994) suitable for the usual fixed and random-effects summaries (DerSimonian and Laird Citation1986). The pooled proportion was calculated as the back-transform of the weighted mean of the transformed proportions, using inverse arcsine variance weights for the fixed-effects model and DerSimonian-Laird weights for the random-effects model. Statistical heterogeneity across studies was measured using the Q statistic (with p < 0.1 considered significant). To determine the percentage of heterogeneity across studies, the I-squared (I2) statistic was calculated (Higgins et al. Citation2003). To explore the reasons for heterogeneity, meta-regression analysis was used to test the relationship between occult fracture prevalence and the following clinical and methodological factors: study design (prospective vs. retrospective), studies including only children with suspicion of distal fibula fractures vs. studies including children with suspicion of any fractures, ankle radiographs (3-view vs. 2-view), reference standard (MRI vs. late radiographs), and criteria for positivity of the reference standard (provided vs. not provided). The Galbraith plot was used to spot the outliers as the possible major sources of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analysis was conducted by examining the effect of excluding the heterogeneous studies. To evaluate the weight of particular articles on the pooled estimates, we performed influence analysis. This method recalculates the pooled prevalence estimate, omitting 1 study at a time. Publication bias was not assessed because of the small number of studies included. The US operating characteristics were assessed in comparison to late radiographs as reference standard. For each individual study exploring the diagnostic accuracy of US, we calculated sensitivities, specificities, and likelihood ratios (LRs). All confidence intervals (CIs) reported are 95% CIs. All statistical tests were performed using STATA version 11.1, StatsDirect version 2.7.9 (StatsDirect Ltd., Altrincham, UK), and Metadisc version 1.4 (Clinical Biostatistics Unit, Ramon y Cajal Hospital, Madrid, Spain).

Results

Search findings and studies selected

We identified 1,763 articles through electronic database search, of which 24 were deemed relevant for full-text review. Reference checking identified 8 additional potentially relevant articles. Of these 32 articles, 9 with an aggregate of 187 patients met all criteria for inclusion ( and ).

Table 1. Characteristics and results of the studies included

Study characteristics

summarizes the main characteristics and results of the studies included. 5 studies used MRI and 4 used late radiographs as reference standard. Of the studies that used late radiographs as reference standard, 2 (conducted by the same group of researchers, including different patient populations) also assessed the diagnostic accuracy of US (). Overall, the quality of the studies included was satisfactory (Table 3, see Supplementary data). 7 studies were prospective and 2 were retrospective. Participants were representative of the target population in all studies, and were described as a consecutive sample in all studies except 1 (Gufler et al. Citation2013), where consecutive recruitment was not reported but was implied. 6 studies included children with suspicion of any ankle fracture and 3 included those with suspicion of distal fibula fracture. Ankle fracture was ruled out by 3-view radiographs in 4 studies, by 2-view radiographs in 2, and not mentioned in 3. Patients with past history of ankle injury were excluded in 4 studies and not mentioned in the others. 5 studies provided a clear definition of criteria for positivity of the reference standard. Outcomes were well documented by reference standard in 100% of patients in all studies.

Table 2. Operating characteristics of ultrasound for diagnosis of occult fractures in children with radiography-negative ankle injury and clinical suspicion of fracture

Occult fracture prevalence

Of the 187 children, 44 were found to have an occult fracture (31 insignificant and 13 significant). The pooled prevalence of occult fractures using a random-effects model was 24% (CI: 18–31) (). There was heterogeneity among the estimates from the studies (I2 = 41%; p = 0.09). On meta-regression, prevalence of occult fracture was lower in studies that included only children with suspicion of distal fibula fracture than in studies that included children with suspicion of any fractures (p = 0.04); none of the other variables investigated (see Methods) were associated with the prevalence estimate. Galbraith plot identified the populations studied by Boutis et al. (Citation2010) and Stuart et al. (Citation1998) as the sources of heterogeneity; however, exclusion of one or both of these studies did not alter the results (p = 0.4). Furthermore, influence analysis showed that omission of no single study significantly affected the pooled prevalence estimate. A formal meta-analysis was not done to calculate the pooled prevalence of significant occult fractures because of the excessive number of zero events in the sample.

Diagnostic accuracy of US

The operating characteristics for detection of occult ankle fractures by US ranged in positive LR from 9 to 20, and in negative LR from 0.04 to 0.08 (). We did not pool the results due to the small number of studies.

Discussion

We have not found any previous systematic reviews or meta-analyses that have attempted to determine the prevalence of occult fractures and their clinical significance in children with radiograph-negative AAI and clinical suspicion of fracture. We found a 24% prevalence of occult fractures with about one-third classified as significant. US showed good diagnostic accuracy in diagnosis of occult ankle fractures.

In children, the radiographic diagnosis of fractures near the growth plate is challenging because ossification of the epiphysis has either not yet taken place or is incomplete. Given the aim of our review, we focused on children with radiograph-negative AAI and clinical suspicion of fracture. As such, we were not able to assess the sensitivity of plain radiographs in the detection of fractures in children with AAI and clinical suspicion of fracture. In a multicenter study in North America that used the same definition of ankle fractures as we did, 45 of 226 children with AAI and high clinical suspicion of fracture were found to have a significant fracture following routine plain radiographs (Boutis et al. Citation2001). Extrapolation of our results (13/187) suggests that approximately 13 of the remaining 181 children (who had negative radiographs) would have had a significant fracture. The total number of significant fractures in these 226 children could therefore be estimated to be 58, one-fifth of which (13/58) were not visible on plain radiographs. Although a coarse estimate, this figure indicates limited sensitivity of plain radiographs in the detection of significant fractures in children with AAI and clinical suspicion of fracture.

The discrepancy between clinical and radiographic findings could lead to both under- treatment and over-treatment. Kan et al. (Citation2009) retrospectively reviewed 204 children with suspected appendicular fractures and negative initial radiographs (22% with ankle injury) who had follow-up related to their injury; one-seventh of these children had a fracture identified on follow-up radiographs. Half of the children without fracture were over-treated and one-third of children with fracture were under-treated (Kan et al. Citation2009). In our review, 13 of 187 children were found to have a significant fracture. Accordingly, about one-tenth of the children included in our review were at risk of under-treatment if based solely on initial plain radiographs, and nine-tenths were at risk of over-treatment if based solely on clinical grounds. This figure illustrates the need for an adjunct to conventional radiography in such cases. Other imaging methods, when clinical findings are suggestive of fracture but plain radiographs are negative, can allow for appropriate care to be instituted at the outset, thereby reducing the risk of both over-treatment and under-treatment.

A variety of imaging methods such as CT (Adey et al. Citation2007, You et al. Citation2007, Stevenson et al. Citation2012), bone scintigraphy (Beeres et al. Citation2008, Querellou et al. Citation2009, Cho et al. Citation2010), MRI (Carey et al. Citation1998, Stuart et al. Citation1998, Launay et al. Citation2008, Boutis et al. Citation2010, Endele et al. Citation2012, Gufler et al. Citation2013), and US (Graif et al. Citation1988, Singh et al. Citation1990, Smeets et al. Citation1990, Gleeson et al. Citation1996, Lazovic et al. Citation1996, Wang et al. Citation1999, Ali et al. Citation2001, Hauger et al. Citation2002, Enns et al. Citation2004, Hsu et al. Citation2013) have been reported to be useful for detecting occult fractures. In children, bone scintigraphy is not favored for this purpose because intense physiological osteoblastic response concentrating radiopharmaceutical at the margin of the growth plate can mask an underlying fracture (Rogers and Poznanski Citation1994). Radiation exposure is a matter of concern when examining children with the CT approach. MRI is extremely helpful for detecting occult fractures and soft tissue abnormalities, especially ligamentous injuries in cases of AAI (Lohman et al. Citation2001, Launay et al. Citation2008). However, high costs, limited availability, and long duration of the MRI examination limit wide application of MRI for AAI. US does not have these limitations; it is a readily available and inexpensive method with no radiation risk. Several studies have demonstrated that US, when performed by trained and experienced operators, is an effective tool for detecting occult ankle fractures and associated soft tissue injuries in children (Gleeson et al. Citation1996, Farley et al. Citation2001, Callahan Citation2013). In our review, we observed a good diagnostic accuracy of US for diagnosing occult ankle fractures (). However, it should be acknowledged that these findings were based on the results of only 2 studies of small size in which late radiographs were used as reference standard.

Our analysis had several limitations. The first limitation relates to the small size of the studies included. However, one important use of meta-analysis of small studies may not be to provide a definitive answer to a question, but to provide a reliable estimate of an outcome probability or the effect of an intervention. That estimate can be used in planning a future study with adequate power to detect such a probability or an effect if it truly exists. Secondly, the use of late radiographs as reference standard is open to debate. While some authors have suggested the use of late radiographs as the final arbiter in the detection of occult fractures (Farley et al. Citation2001, Sankar et al. Citation2008, Simanovsky et al. Citation2009), others have questioned its validity (Tiel-van Buul et al. Citation1997). However, in our review, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of occult fractures between studies using late radiographs and those that used MRI as reference standard. Finally, there was slight heterogeneity across studies. This could be explained by the differences in injury patterns among patients included in the different studies; a lower prevalence rate of occult fractures was found in the studies that included only children with suspicion of distal fibula fracture. However, exclusion of the outlier studies did not substantially alter the results. We also applied a random-effects model to take variation between studies into consideration.

In conclusion, our findings provide evidence that in children with AAI and clinical suspicion of fracture, a substantial proportion of fractures could be missed initially because radiographic evidence of such fractures may not appear until weeks after the initial injury. US appears to be a promising method for detecting occult fractures and associated soft tissue lesions in such children. However, given the small number of patients included in our review, further studies with an adequate sample size are needed to provide a more reliable estimate of such fractures, and to assess the true role of US in these children.

Supplementary data

Appendix and Table 3 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 7259.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (49.4 KB)AN, EN, FD, XD, and AM designed the study protocol. AN, EN, and AM designed the search strategy for the literature search. AN and EN selected the articles, gathered the data, and performed the study quality assessment. AN, EN, FD, and AM performed statistical analysis. All the authors contributed to writing and presentation of the manuscript and approved the final version.

No competing interests declared.

Notes

- Adey L, Souer JS, Lozano-Calderon S, Palmer W, Lee SG, Ring D. Computed tomography of suspected scaphoid fractures. J Hand Surg Am 2007; 32 (1): 61-6.

- Ali S, Finlay K, Friedman L, Jurriaans E, Chhem RK. Ultrasonography of occult fractures: a pictorial essay. Can Assoc Radiol J 2001; 52 (5): 312-21.

- Beeres FJ, Rhemrev SJ, den Hollander P, Kingma LM, MeylaertsSAle Cessie S, et al. Early magnetic resonance imaging compared with bone scintigraphy in suspected scaphoid fractures. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90 (9): 1205-9.

- Boutis K, Komar L, Jaramillo D, Babyn P, Alman B, Snyder B, et al. Sensitivity of a clinical examination to predict need for radiography in children with ankle injuries: a prospective study. Lancet 2001; 358 (9299): 2118-21.

- Boutis K, Narayanan UG, Dong FF, MacKenzie H, Yan H, Chew D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of clinically suspected Salter–Harris I fracture of the distal fibula. Injury 2010; 41 (8): 852-6.

- Callahan MJ. Musculoskeletal ultrasonography of the lower extremities in infants and children. Pediatr Radiol 2013; 43 (1): 8-22.

- Carey J, Spence L, Blickman H, Eustace S. MRI of pediatric growth plate injury: correlation with plain film radiographs and clinical outcome. Skeletal Radiol 1998; 27 (5): 250-5.

- Cho K-H, Lee S-M, Lee Y-H, Suh K-J. Ultrasound diagnosis of either an occult or missed fracture of an extremity in pediatric-aged children. Korean J Radiol 2010; 11 (1): 84-94.

- Cockshott WP, Jenkin JK, Pui M. Limiting the use of routine radiography for acute ankle injuries. Can Med Assoc J 1983; 129 (2): 129-31.

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986; 7 (3): 177-88.

- Endele D, Jung C, Bauer G, Mauch F. Value of MRI in diagnosing injuries after ankle sprains in children. Foot Ankle Int 2012; 33 (12): 1063-8.

- Enns P, Pavlidis T, Stahl J P, Horas U, Schnettler R. Sonographic detection of an isolated cuboid bone fracture not visualized on plain radiographs. J Clin Ultrasound 2004; 32 (3): 154-7.

- Farley FA, Kuhns L, Jacobson JA, DiPietro M. Ultrasound examination of ankle injuries in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2001; 21 (5): 604-7.

- Gleeson A, Stuart M, Wilson B, Phillips B. Ultrasound assessment and conservative management of inversion injuries of the ankle in children: plaster of Paris versus Tubigrip. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1996; 78 (3): 484-7.

- Graif M, Stahl-Kent V, Ben-Ami T, Strauss S, Amit Y, Itzchak Y. Sonographic detection of occult bone fractures. Pediatr Radiol 1988; 18 (5): 383-5.

- Gufler H, Schulze CG, Wagner S, Baumbach L. MRI for occult physeal fracture detection in children and adolescents. Acta Radiol 2013; 54 (4): 467-72.

- Hauger O, Bonnefoy O, Moinard M, Bersani D, Diard F. Occult fractures of the waist of the scaphoid: early diagnosis by high-spatial-resolution sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2002; 178 (5): 1239-45.

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta- analyses. BMJ 2003; 327 (7414): 557-60.

- Hsu CY, Chiang YP, Liao CT, Hong YC. Sonographic diagnosis of a medial talar avulsion fracture. J Clin Ultrasound 2013: 41(9):570-3

- Jüni P, Witschi A, Bloch R, Egger M. The hazards of scoring the quality of clinical trials for meta-analysis. JAMA 1999; 282 (11): 1054-60.

- Kan J, Estrada C, Hasan U, Bracikowski A, Shyr Y, Shakhtour B, et al. Management of occult fractures in the skeletally immature patient: cost analysis of implementing a limited trauma magnetic resonance imaging protocol. Pediatr Emerg Care 2009; 25 (4): 226-30.

- Kendall M, Stuart A, Ord JK, O’Hagan A. Kendall’s advanced theory of statistics, volume 1: Distribution theory. Arnold, sixth edition 1994.

- Launay F, Barrau K, Petit P, Jouve J, Auquier P, Bollini G. [Ankle injuries without fracture in children. Prospective study with magnetic resonance in 116 patients]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 2008; 94 (5): 427-33.

- Lazovic D, Wegner U, Peters G, Gosse F. Ultrasound for diagnosis of apophyseal injuries. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 1996; 3 (4): 234-7.

- Loder RT, Warschausky S, Schwartz EM, Hensinger RN, Greenfield ML. The psychosocial characteristics of children with fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 1995; 15 (1): 41-6.

- Lohman M, Kivisaari A, Kallio P, Puntila J, Vehmas T, Kivisaari L. Acute paediatric ankle trauma: MRI versus plain radiography. Skeletal Radiol 2001; 30 (9): 504-11.

- Marsh JS, Daigneault JP. Ankle injuries in the pediatric population. Curr Opin Pediatr 2000; 12 (1): 52-60.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 2009; 6 (7): e1000097.

- Ogden J. The evaluation and treatment of partial physeal arrest. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1987; 69 (8): 1297-302.

- Pijnenburg A, Van Dijk C, Bossuyt P, Marti R. Treatment of Ruptures of the Lateral Ankle Ligaments: A Meta-Analysis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2000; 82 (6): 761-73.

- Prosser I, Maguire S, Harrison SK, Mann M, Sibert JR, Kemp AM. How old is this fracture? Radiologic dating of fractures in children: a systematic review. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005; 184 (4): 1282-6.

- Querellou S, Moineau G, Le Duc-Pennec A, Guillo P, Turzo A, Cotonea Y, et al. Detection of occult wrist fractures by quantitative radioscintigraphy: a prospective study on selected patients. Nucl Med Commun 2009; 30 (11): 862-7.

- Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Guyatt GH, Cook DJ, Nishikawa J. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature XV. How to use an article about disease probability for differential diagnosis. JAMA 1999; 281 (13): 1214-9.

- Rogers LF, Poznanski AK. Imaging of epiphyseal injuries. Radiology 1994; 191 (2): 297-308.

- Sankar WN, Chen J, Kay RM, Skaggs DL. Incidence of occult fracture in children with acute ankle injuries. J Pediatr Orthop 2008; 28 (5): 500-1.

- Simanovsky N, Hiller N, Leibner E, Simanovsky N. Sonographic detection of radiographically occult fractures in paediatric ankle injuries. Pediatr Radiol 2005; 35 (11): 1062-5.

- Simanovsky N, Lamdan R, Hiller N, Simanovsky N. Sonographic detection of radiographically occult fractures in pediatric ankle and wrist injuries. J Pediatr Orthop 2009; 29 (2): 142-5.

- Singh A, Malpass T, Walker G. Ultrasonic assessment of injuries to the lateral complex of the ankle. Arch Emerg Med 1990; 7 (2): 90-4.

- Smeets A, Robben S, Meradji M. Sonographically detected costo-chondral dislocation in an abused child. Pediatr Radiol 1990; 20 (7): 566-7.

- Stevenson J, Morley D, Srivastava S, Willard C, Bhoora I. Early CT for suspected occult scaphoid fractures. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2012; 37 (5): 447-51.

- Stuart J, Boyd R, Derbyshire S, Wilson B, Phillips B. Magnetic resonance assessment of inversion ankle injuries in children. Injury 1998; 29 (1): 29-30.

- Tiel-van Buul M, Roolker W, Broekhuizen A, Van Beek E. The diagnostic management of suspected scaphoid fracture. Injury 1997; 28 (1): 1-8.

- Vasukutty NV, Akrawi H, Theruvil B, Uglow M. Ankle arthroscopy in children. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2011; 93 (3): 232-5.

- Wang CL, Shieh JY, Wang TG, Hsieh FJ. Sonographic detection of occult fractures in the foot and ankle. J Clin Ultrasound 1999; 27 (8): 421-5.

- You JS, Chung SP, Chung HS, Park IC, Lee HS, Kim SH. The usefulness of CT for patients with carpal bone fractures in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2007; 24 (4): 248-50.