Abstract

Background and purpose — A shortened tibial stem could influence the early prosthetic fixation. We therefore compared the short stem to the standard-length stem using radiostereometric analysis (RSA) as primary outcome measure.

Patients and methods — 60 patients were randomized to receive a cemented Triathlon total knee arthroplasty (TKA) with a tibial tray of either standard or short stem length. The patients were blinded regarding treatment allocation. The micromotion of the tibial component was measured by RSA postoperatively, at 3 months, and after 1 and 2 years; clinical outcome was measured with the American Knee Society score (AKSS) and the knee osteoarthritis and injury outcome score (KOOS).

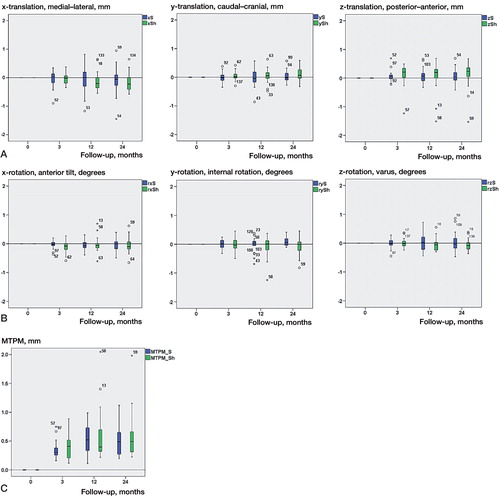

Results — The maximum total point motion (MTPM) for the standard stem was 0.36 (SD 0.16) mm at 3 months, 0.51 (SD 0.27) mm at 1 year, and 0.54 (SD 0.28) mm at 2 years. For the short stem, it was 0.42 (0.24) mm, 0.59 (0.43) mm, and 0.61 (0.39) mm. 4 short-stemmed components and 2 standard-stemmed components had more than 0.2 mm of migration between the first- and second-year follow-up, and were classified as continuously migrating.

Interpretation — The short-stemmed cemented tibial prosthesis showed an early prosthetic migratory pattern similar to that of the standard-stemmed cemented Triathlon knee prosthesis. The number of continuously migrating tibial plates in each group is predictive of a lower revision rate than 5% at 10 years.

The ongoing developments in component design are aimed at better stability, shorter stem length, or pegs to follow the rationale of minimally invasive surgical techniques and to preserve bone stock in cases of revision. A stem has the advantages of resistance to shear, reduced tibial lift-off, and increased stability by reducing micromotion, but it also has disadvantages such as reduction in bone density and a theoretical risk of subsidence and loosening, periprosthetic fracture, and end-of-stem pain which may be associated with stem length and stress shielding. These features make long stems unattractive in primary TKA, but often desirable in revision surgery (CitationScott and Biant 2012).

A study on the influence of the tibial stem design on tibial bone mineral density (BMD) in cemented TKA showed that a cylindrical stem reduced the BMD in a more heterogeneous fashion than a delta-shaped stem design. The heterogeneous BMD deficit pattern was thought to reflect negatively on the stability compared to the more homogenous BMD deficit shown by the delta-shaped design (CitationHernandez-Vaquero et al. 2008). The stem design of Triathlon with segmental delta-shaped fins and no cylindrical central stem has evolved from the Osteonics Series 7000 and Scorpio (Stryker, Mahwah, NJ). Earlier RSA studies regarding Triathlon have predicted good stability of the tibial standard stem baseplate (CitationMolt et al. 2012, Citation2014, CitationMolt and Toksvig-Larsen 2014a, b).

A concern that arises with any new prosthesis is whether or not it will achieve satisfactory long-term implant stability. During the last decades, RSA has emerged as a way of assessing prosthetic fixation and it has been used extensively in both hip and knee arthroplasty. New concepts should be evaluated according to a standardized model before launch (CitationFaro and Huiskes 1992, CitationMalchau 2000, CitationPijls 2013).

We compared the early micromotion of the short-stem tibial baseplate to that of the standard-stem tibial baseplate (with all other design features being equal), using RSA as the primary outcome measure of migration and the number of continuously migrating components as predictor of loosening at 10 years (CitationRyd et al. 1995).

Patients and methods

Study design

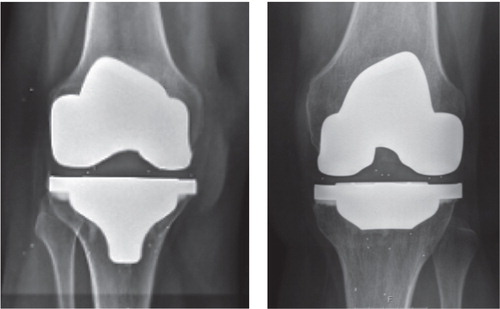

This was a single-center study conducted at Hässleholm Hospital in southern Sweden between February 2008 and November 2010. 59 patients (31 women) with osteoarthritis of the knee were prospectively randomized to receive either a cemented cruciate retaining (CR) TKA with a tibial stem of standard length or a CR TKA with a short tibial stem (Triathlon; Stryker) ().

Randomization was done using sealed envelopes drawn by the department’s study coordinator, with 30 patients allocated to the “standard stem” group and 29 patients allocated to the “short stem” group. 1 patient was lost from the study due to a misplaced envelope. This randomization technique meant that neither the study coordinator nor the surgeons were blinded.

Participants

Patients were considered for enrollment according to the clinical findings, and depended on obtaining written informed consent according to ICH GCP requirements. The main inclusion criterion was OA of stage II–IV (CitationAhlbäck 1968). Inclusion was performed by the surgeons (MM, STL, or CFN). For details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria, see Tables 1 and 2, Supplementary data.

During the period of the trial, 164 total knee replacements were performed using the Triathlon CR total knee system with either a standard stem or a short stem. Of the 164 patients, 104 could not be included because of a long travelling time for follow-up, due to their declining participation, or for not having met the inclusion criteria. 60 patients (60 knees) were included in the study, with 29 patients randomized to the “standard stem” group and 30 patients to the “short stem” group. The 2 groups were similar in terms of patient demographics (Table 3, Supplementary data).

At 2 years, 28 patients were available for RSA follow-up in each group. 24 and 25 patients had valid examinations at both 1 and 2 years in the “standard stem” group and the “short stem” group, respectively. In the “standard stem” group, 1 patient left the study for personal reasons. In the “short stem” group, 1 patient left the study for personal reasons and 1 patient left the study due to neoplastic disease. There were no other clinical events.

Prosthesis

All patients received a chrome-cobalt cemented femoral and tibial component. Both the standard-stem and short-stem components (CR insert) were prepared for horizontal cemented fixation with Refobacin bone cement R (Biomet Inc., Warsaw, IN). The tibial component was cemented at the cut surface, avoiding cementation around the stem but creating a press-fit stem fixation. A patellar component was used in 3 knees in the “standard stem” group and in 1 knee in the “short stem” group.

Operative technique

Each patient was given antibiotics and tranexamic acid preoperatively. The operations were performed via a midline incision with a parapatellar medial entrance to the joint using appropriate guide instruments according to the surgical-technique manual supplied with the knee system. At the time of surgery, 8 tantalum markers (0.8 mm in diameter; RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden) were inserted into the proximal tibial metaphysis and 5 markers were inserted in the polyethylene tibial insert (CitationRyd 1986). Low-molecular-weight heparin was given postoperatively. Mobilization was similar for both groups and included full weight bearing immediately.

Radiographs and RSA

The primary outcome measure of the study was migration of the tibial component, as measured by RSA. The first RSA investigation was performed after weight bearing at median 3 (1–11) days, and then at 3 months and 1 and 2 years postoperatively.

RSA was performed with the patient in supine position, with the knee inside a calibration cage (Cage 10; RSA Biomedical). The 3D migration of the tibial component was measured using UmRSA software (version 6.0; RSA Biomedical) (CitationBorlin et al. 2002).

The migration was described as segment motion (translation and rotation) of the geometric center of the prosthetic markers. The maximum total point motion (MTPM), the 3D motion of the prosthetic marker moving the most, was used as a simplistic way of denoting the magnitude of the micromotion and enabled the micromotion between the tibial insert and the tibial bone to be described. Positive directions for translations along the orthogonal axes were: transverse (medial to lateral), longitudinal (caudal to cranial), and sagittal (posterior to anterior). Positive directions for rotations about the coordinate axes were anterior tilt (transverse axis), internal rotation (longitudinal axis), and varus (sagittal axis). An increase in MTPM of more than 0.2 mm between the first-year and second-year follow-up was considered to be continuous migration (CitationRyd et al. 1995), and these patients were classified as being “at risk” of future implant loosening. In order to ensure accuracy of the measurements, stable fixation of the tantalum markers within the bone was essential. The upper limit for mean error (ME) of rigid body fitting (a measure of marker stability) was 0.2 mm, and the upper limit for condition number was 100. The upper limit for ME of rigid body fitting and condition number is generally proposed to be 0.35 mm and 150, respectively (CitationValstar et al. 2005).

The mean error of rigid body fitting describes the perturbation (in mm) of the markers in the bone and implant, from the postoperative examination to the latest examination. The condition number describes the spatial spread of the markers; a low number indicates a wide spatial orientation and a high number indicates a close-to-linear orientation. Tantalum markers were considered to be unstable if they moved more than 0.3 mm relative to the other tantalum markers between examinations. Unstable markers were excluded from the analysis.

The repeatability of this investigation is described as 2× SD (95% CI) for all rotations and translations. The precision of the RSA system was 0.12 mm, 0.21 mm, and 0.14 mm for x-, y-, and z-translations, and 0.12°, 0.11°, and 0.09° for x-, y-, and z-rotations (CitationValstar et al. 2005, CitationMolt et al. 2012).

Hip-knee-ankle (HKA) measurements were done preoperatively and at the 3-month follow-up (in this study, varus was < 180° and valgus was > 180°).

Clinical evaluation

Clinical evaluation took place preoperatively and at 3 months, 1 year, and 2 years postoperatively, and consisted of AKSS (CitationInsall et al. 1989) and KOOS (CitationRoos et al. 1998) questionnaires. The patients were evaluated by physiotherapists during the follow-up period.

Statistics

Continuous implant migration is predictive of long-term implant survival and provides a surrogate outcome measure with relatively low numbers of subjects, e.g. 15–25 patients in each group in randomized studies (CitationKärrholm et al. 1994, CitationRyd et al. 1995, CitationValstar et al. 2005).

In previous studies, micromotion during the first 2 years for total knee prostheses has been about 1.0 (SD 0.5) mm (MTPM). If this micromotion was to decrease by 50% to 0.5 (0.5) mm, considering an alpha level of 0.05 (significance) and a beta level of 0.20 (power ~80%), this would require 17 cases in each group. With a beta level of 0.75, 15 patients in each group would be needed. Continuous migration between the first-year and second-year follow-up has been found in up to 50% of cases. Supposing that an improvement would mean a decrease in continuous migration of 10% in order to be clinically relevant, an alpha level of 0.05 and a beta level of 0.20 (power = 80%) would require 25 cases in each group. Due to the risk of patient dropout, 30 patients were included in each group.

Quantitative variables were considered to be continuous and were measured either by the interval or the ratio scale. Variables considered quantitative were translation (interval scale), rotation (interval scale), MTPM (ratio scale), PROM (ratio scale), and HKA (ratio scale).

Qualitative variables were measured either by the ordinal scale or the nominal scale. Variables considered qualitative were gender (nominal scale), affected side (left/right) (nominal scale), Ahlbäck classification (ordinal scale), and continuous migration (nominal scale).

Depending on the nature of the study variables, descriptive (for quantitative data measured by the interval or the ratio scale for continuous variables) or frequencies (for qualitative variables measured by the ordinal or the nominal scale) are given.

The difference between the 2 treatment groups was evaluated with ANOVA for continuous variables at different time periods. Clinical scores were also analyzed using ANCOVA to compensate for different preoperative starting values. Continuous data that were not normally distributed were analyzed with non-parametric ranking tests, and proportional values were analyzed with Fisher’s exact test.

All p-values given are 2-sided and they were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Any p-value less than 0.05 was taken to indicate statistical significance. The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 17.0.

Ethics and registration

Approval was obtained from the local medical ethics committee (no. 445/2005) prior to initiation of the study. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier: NCT00436982).

Results

RSA and radiographs

There were no statistically significant differences in rotation or translation around or along the 3 coordinate axes, or in maximum total point motion (MTPM) (; Table 4, Supplementary data). 2 out of 24 tibial trays in the “standard stem” group showed continuous migration between the first-year and the second-year follow-up. 4 out of 25 tibial trays in the “short stem” group showed continuous migration. There were no statistically significant differences in HKA between groups, either preoperatively or postoperatively (Table 5, Supplementary data).

Figure 2. Box plots for translation in mm (A), rotation in degrees (B), and MTPM in mm (C). S: standard stem (blue); Sh: short stem (green). No statistically significant differences were found between groups at any time point, except for posterior-anterior translation at 24 months. Independent-samples Mann-Whitney U test.

Clinical outcome

The clinical outcome scores (AKSS and KOOS) were similar between the 2 groups (Table 6, Supplementary data).

Discussion

As there is a correlation between excessive early migration and continuous migration of the implant and a greater risk of implant failure (CitationRyd et al. 1995), RSA should be used to evaluate new implants or design modifications to provide an early indication of long-term fixation (CitationKärrholm 2012, CitationMalchau 2000, CitationRyd 1986, Citation1992). The number of continuously migrating components (MTPM > 0.2 mm between years 1 and 2) was low in both groups, and comparable to findings in earlier studies (CitationHansson et al. 2005, CitationMolt et al. 2012 and Citation2014, CitationMolt and Toksvig-Larsen 2014a, Citationb). According to Ryd et al., if classified as continuously migrating, the approximate risk of becoming mechanically loose is ~85%. The risk of becoming clinically loose and in need of revision is 20%. This would mean that of the 6 patients who showed continuous migration in this study (2/24 and 4/25), ~5 were mechanically loose and therefore ~1 carried a risk of becoming clinically loose and in need of revision within the first 10 postoperative years; so the risk of revision because of aseptic loosening would be ~2% (1/49) for the combined data. If the 9 patients with inconclusive RSA data are added to the continuously migrating group (6 + 9), the ratio of patients being at risk of revision would be predicted to be less than 5% at 10 years (~3%).

We could not confirm the findings by Ries et al. (2013), who recently showed a higher revision rate in a group of cemented short-stem TKAs. This might be explained by the use of a cylindrical stem design with reduced fins in the Ries study (Genesis II MIS tibial tray; Smith and Nephew, Memphis, TN) and the finding of a more homogeneous decrease in BMD in proximal tibia, when using a delta form instead of a cylindrical stem design (CitationHernandez-Vaquero et al. 2008). The segmental delta-shaped stem design could be one explanation for the small number of continuously migrating prostheses in our study and previous studies with the same implant (CitationMolt et al. 2012 and 2014).

The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (with patients operated on between 2002 and 2011) has reported that the Triathlon prosthesis (standard stem) has a revision risk ratio of 0.47 (95% CI: 0.32–0.68) compared to the AGC prosthesis (Biomet), which was referred to as the gold standard (CitationSKAR 2013) (when not considering reoperation with a change of insert as revision). The 5-year revision rate for the Triathlon prosthesis in other registries ranges from 1.9% to 3.0% (CitationAOANJRR 2013, CitationNJR 2013). One benefit of using a short stem might be the lower bone loss expected in cases of revision. Short stems may facilitate minimally invasive surgery (CitationDabboussi et al. 2012), and give better alignment, but there was no difference between group means in HKA alignment in the present study.

As there was a tendency of greater translational and rotational movements in the group with a short-stem tibia at 2 years, longer-term follow-up would be required for further comparison to standard stems.

Approximately one-third of all patients who underwent TKA during the time period of this series were included, so there was a risk of selection bias. In contrast to our other studies (CitationMolt et al. 2012, Citation2014, CitationMolt and Toksvig-Larsen 2014a, Citationb), we had no complications, which is probably a random finding.

In summary, the RSA results at 2 years predicted that as with the Triathlon standard stem, the Triathlon short tibial stem would have a stem revision rate of less than 5% at 10 years.

Supplementary data

Tables 1–6 are available at Acta’s website (www.actaorthop.org), identification number 8132.

IORT_A_1033303_SM1613.pdf

Download PDF (40.2 KB)STL designed the study and coordinated it. MM participated in the design of the study. MM prepared the manuscript.

Stryker funded the cost for RSA and extra outpatient clinical follow-up examinations. Stryker did not take part in the evaluation of results or writing of the paper. No other competing interests declared.

We thank our study coordinator Marie Davidsson for her excellent help in monitoring the patients. We also thank our colleague Carsten Feldborg-Nielsen MD for his help in the work with inclusion and surgery.

- Ahlbäck S. Osteoarthrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1968: Suppl 277:7–72.

- AOANJRR. Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report Adelaide AOA 2013.

- Borlin N, Thien T, Karrholm J. The precision of radiostereometric measurements. Manual vs. digital measurements. J Biomech 2002; 35 (1): 69–79.

- Dabboussi N, Sakr M, Girard J, Fakih R. Minimally invasive total knee arthroplasty: a comparative study to the standard approach. North American journal of medical sciences 2012; 4 (2): 81–5.

- Faro LM, Huiskes R. Quality assurance of joint replacement. Legal regulation and medical judgement. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1992; 250: 1–33.

- Hansson U, Toksvig-Larsen S, Jorn LP, Ryd L. Mobile vs. fixed meniscal bearing in total knee replacement: a randomised radiostereometric study. Knee 2005; 12 (6): 414–8.

- Hernandez-Vaquero D, Garcia-Sandoval MA, Fernandez-Carreira JM, Gava R. Influence of the tibial stem design on bone density after cemented total knee arthroplasty: a prospective seven-year follow-up study. Int Orthop 2008; 32 (1): 47–51.

- Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1989; (248): 13–4.

- Kärrholm J. Radiostereometric analysis of early implant migration - a valuable tool to ensure proper introduction of new implants. Acta Orthop 2012; 83 (6): 551–2.

- Kärrholm J, Borssen B, Lowenhielm G, Snorrason F. Does early micromotion of femoral stem prostheses matter? 4-7-year stereoradiographic follow-up of 84 cemented prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1994; 76 (6): 912–7.

- Malchau H. Introducing new technology: a stepwise algorithm. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000; 25 (3): 285.

- Molt M, Toksvig-Larsen S. Peri-apatite enhances prosthetic fixation in TKA-A prospective randomised study. J Arthritis 2014a; 3 (134): 10.4172/2167-7921.1000134.

- Molt M, Toksvig-Larsen S. Similar early migration when comparing CR and PS in Triathlon TKA: A prospective randomised RSA trial. Knee 2014b; 21(5): 949–54.

- Molt M, Ljung P, Toksvig-Larsen S. Does a new knee design perform as well as the design it replaces? Bone Joint Res 2012; 1 (12): 315–23.

- Molt M, Harsten A, Toksvig-Larsen S. The effect of tourniquet use on fixation quality in cemented total knee arthroplasty a prospective randomized clinical controlled RSA trial. Knee 2014; 21 (2): 396–401.

- NJR. National Joint Registry for England and Wales, 10th Annual Report. National Joint Registry for England and Wales, 10th Annual Report. 2013.

- Pijls BG. Evidence based introduction of orthopaedic implants. RSA, implant quality and patient safety. Evidence based introduction of orthopaedic implants. RSA, implant quality and patient safety. Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, The Netherlands. PhD Thesis 2013.

- Roos EM, Roos HP, Ekdahl C, Lohmander LS. Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS)--validation of a Swedish version. Scand J Med Sci Sports 1998; 8 (6): 439–48.

- Ryd L. Micromotion in knee arthroplasty. A roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis of tibial component fixation. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl 1986; 220: 1–80.

- Ryd L. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis of prosthetic fixation in the hip and knee joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992; (276): 56–65.

- Ryd L, Albrektsson BE, Carlsson L, Dansgard F, Herberts P, Lindstrand A, et al. Roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis as a predictor of mechanical loosening of knee prostheses. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995; 77 (3): 377–83.

- Scott CE, Biant LC. The role of the design of tibial components and stems in knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94 (8): 1009–15.

- SKAR. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Annual Report. Lund: Dept. of Orthopedics, Skåne University Hospital, 2013. 2013.

- Valstar ER, Gill R, Ryd L, Flivik G, Borlin N, Karrholm J. Guidelines for standardization of radiostereometry (RSA) of implants. Acta Orthop 2005; 76 (4): 563–72.