Abstract

Background and purpose — In some patients, for unknown reasons pain persists after joint replacement, especially in the knee. We determined the prevalence of persistent pain following primary hip or knee replacement and its association with disorders of glucose metabolism, metabolic syndrome (MetS), and obesity.

Patients and methods — The incidence of pain in the operated joint was surveyed 1–2 years after primary hip replacement (74 patients (4 bilateral)) or primary knee replacement (119 patients (19 bilateral)) in 193 osteoarthritis patients who had participated in a prospective study on perioperative hyperglycemia. Of the 155 patients who completed the survey, 21 had undergone further joint replacement surgery during the follow-up and were excluded, leaving 134 patients for analysis. Persistent pain was defined as daily pain in the operated joint that had lasted over 3 months. Factors associated with persistent pain were evaluated using binary logistic regression with adjustment for age, sex, and operated joint.

Results — 49 of the134 patients (37%) had a painful joint and 18 of them (14%) had persistent pain. A greater proportion of knee patients than hip patients had a painful joint (46% vs. 24%; p = 0.01) and persistent pain (20% vs. 4%; p = 0.007). Previously diagnosed diabetes was strongly associated with persistent pain (5/19 vs. 13/115 in those without; adjusted OR = 8, 95% CI: 2–38) whereas MetS and obesity were not. However, severely obese patients (BMI ≥ 35) had a painful joint (but not persistent pain) more often than patients with BMI < 30 (14/21 vs. 18/71; adjusted OR = 5, 95% CI: 2–15).

Interpretation — Previously diagnosed diabetes is a risk factor for persistent pain in the operated joint 1–2 years after primary hip or knee replacement.

Many patients continue to experience pain after joint replacement. Persistent pain is defined as pain that develops after surgery and that has been present for over 3 months (International Association for the Study of Pain 1986) and its prevalence is underestimated (CitationVisser 2006). According to CitationBeswick et al. (2012), at least 5–21% of hip replacement recipients and 8–27% of knee replacement recipients suffer from persistent pain postoperatively.

Persistent pain is generally thought to be of neuropathic origin and caused by perioperative nerve damage (CitationKehlet et al. 2006). However, neuropathic pain appears to be rare in joint replacement patients (CitationWylde et al. 2011). Instead, these patients often describe their pain in a way that indicates the presence of an inflammatory factor (CitationWylde et al. 2011). The degree of the inflammatory state is associated with the severity of preoperative pain in patients with osteoarthritis (CitationStürmer et al. 2004). In addition, the intensity and duration of preoperative pain correlates with persistent postoperative pain in knee replacement surgery (CitationLundblad et al. 2008, CitationPuolakka et al. 2010). Other established risk factors for persistent pain include genetic factors, history of preoperative pain, depression, existence of other chronic pain sites, and psychosocial factors (CitationKehlet et al. 2006, CitationNikolajsen et al. 2006, CitationRolfson et al. 2009).

Low-grade systemic inflammation is associated with the pathogenesis of diabetes, metabolic syndrome (MetS; a clustering of cardiovascular risk factors including abdominal obesity, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and impaired glucose metabolism (CitationAlberti et al. 2009)), and obesity. All these conditions are common in joint replacement recipients (CitationMeding et al. 2007, Gonzales Della CitationValle et al. 2012, Workgroup of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons Evidence Based Committee 2013). Diabetes is associated with poor postoperative outcomes, including reduced joint function (CitationRobertson et al. 2012) and slower recovery in terms of pain and function (CitationJones et al. 2012). Obesity is associated with slower recovery, especially in knee patients (Workgroup of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons Evidence Based Committee 2013). It has been hypothesized that the systemic proinfammatory state in MetS negatively affects patients’ function and recovery after joint replacement (CitationGandhi et al. 2010). To our knowledge, the effect of disorders of glucose metabolism, MetS, and obesity on persistent pain after joint replacement has not been studied previously.

We therefore determined whether glucose metabolism disorders, MetS, and obesity are associated with persistent pain in the operated joint 1–2 years after primary joint replacement.

Patients and methods

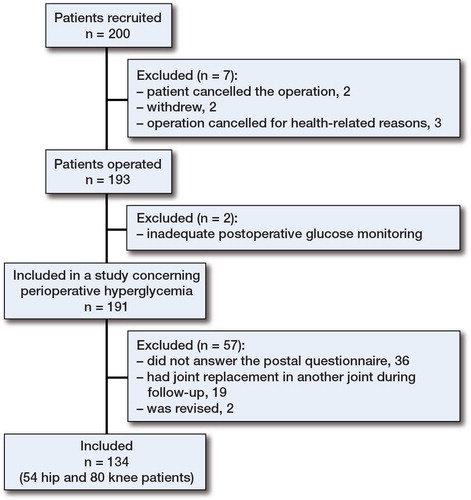

Between December 2009 and May 2011, 200 patients scheduled for primary hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis in a single orthopedic hospital were recruited in a prospective study concerning perioperative hyperglycemia (“Perioperative hyperglycemia in primary total hip and knee replacement”; clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01021826). Patients of all ages with or without previously diagnosed diabetes were eligible. The exclusion criteria were an arthritis diagnosis other than osteoarthritis and regular oral corticosteroid treatment. The patients were closely comparable to other patients undergoing primary hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis in the same hospital during the study period (n = 2,565) in terms of sex (the proportion of females in the study population was 65% as compared to 63% in the other patients; p = 0.6) and in terms of joint operated (the proportion of knee replacements in the study population was 61% as compared to 57% in the other patients; p = 0.3), but the mean age was lower in the study population (66 (SD 9) years vs. 68 (SD 11) years; p = 0.002).

Of the 200 patients, 191 were operated on and were enrolled in this prospective observational follow-up study. Pain in the operated joint was surveyed 1–2 years after the operation, using a postal questionnaire. The response rate was 81% (155/191). After exclusion of patients who had undergone later operations, the study population consisted of 134 patients (80 knee patients and 54 hip patients) ().

The study protocol concerning preoperative diagnostics, perioperative treatment, and postoperative care has been described previously in detail (CitationJämsen et al. 2014). In short, a research nurse evaluated the patients carefully 6–8 weeks before surgery and recorded their medical history.

In addition to preoperative laboratory routines, measurements were performed to diagnose MetS and diabetes, as these conditions are often undiagnosed in many patients (CitationMeding et al. 2007). Thus, diagnoses based on patient reports or patient records are not reliable. Fasting plasma glucose, blood glycosylated hemoglobin A1 (HbA1c), and plasma lipids (LDL and HDL cholesterol, triglycerides) were measured in all patients. Patients without previously diagnosed diabetes had a 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test with an oral glucose dose of 75 g (CitationWHO 2006).

Patient characteristics ()

Table 1. Baseline characteristics (n = 134)

Almost half of the patients were obese (BMI ≥ 30). The prevalence of diabetes was 25% (34/134), and 24% (32/134) had increased fasting glucose (IFG) or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). 19 patients were already diagnosed as having diabetes before recruitment, 4 of whom were being treated with insulin, and 15 patients were diagnosed in this study. Almost two-thirds of the patients had MetS. The median (range) duration of follow-up was 18 (11–28) months. No statistically significant differences in age, sex, operated joint, BMI, prevalence of glucose metabolism disorders, or prevalence of MetS were found between those who responded to the questionnaire and those who did not.

Severely obese participants were significantly younger (median 63 years) than obese participants (median 66 years) and non-obese participants (median 68 years) (p = 0.02). Men more often had IFG or IGT (31% vs. 20%) and diabetes (33% vs. 21%) than women (p = 0.04). Also, MetS was more common in men (76% vs. 57%, p = 0.04). Median BMI was higher in patients with diabetes (33) and IFG or IGT (30) than in patients with normal glucose metabolism (27; p = 0.002). Patients with MetS were significantly more obese than patients without MetS (median BMI 32 vs. 27; p < 0.001). The severity of preoperative pain at rest was milder in patients with disorders of glucose metabolism (). No significant differences were found between the subgroups of patients with glucose metabolism disorders, MetS, or obesity regarding joint replaced, proportion of bilateral operations, proportion of unicompartmental knee replacements, proportion of former joint replacements, average follow-up time, and severity of osteoarthritis, as assessed with the Kellgren-Lawrence grading scale (data not shown).

Table 2. Preoperative pain by VAS scale (0–100) in 110 patients who filled in the VAS scale. Values are median (range).

The operations were mainly performed by experienced senior orthopedic surgeons. All operations were performed under spinal anesthesia. Acetaminophen and/or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were used as routine analgesics and they were supplemented with oxycodone when necessary. Epidural analgesia using a continuous levobupivacaine infusion (1.25 mg/mL) was inserted if needed after routine and supplementary medication. Most of the operations were unilateral (90%) and a total joint replacement was implanted in all patients except for 8 unicompartmental knee replacements (6%). Most of the knee replacements were cemented (74%) whereas hip replacements were mostly cementless (67%). Antibiotic-impregnated cement was used in all cemented joint replacements. A pneumatic tourniquet was used in all knee replacements. Median length of hospital stay was 4 (1–6) days.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was occurrence of persistent pain in the operated joint. The pain questions were based on the classification of chronic pain (CitationInternational Association for the Study of Pain 1986) and they were as follows: “Do you have pain in the operated knee or hip?”, “Is there pain in the operated knee or hip every day?” and “Has the pain in the operated knee or hip been there continuously for over 3 months?”. The patient was deemed to have persistent pain if he or she answered “yes” to all 3 questions. Prevalence of having a painful joint was a secondary outcome and it was assessed by the answer to the first pain question.

The Finnish version of the PainDetect questionnaire (CitationFreynhagen et al. 2006) was included in the postal questionnaire to determine whether the pain reported was of neuropathic origin. The PainDetect questionnaire was originally developed for patients with back pain, but it has also been used to examine postoperative pain in joint replacement patients (CitationWylde et al. 2011).

Statistics

The analyses were done for subgroups of patients according to whether they had disorders of glucose metabolism, had MetS, or were obese. In order to maximize statistical power, knee and hip replacements were analyzed together, but the analyses were also re-run separately.

The disorders of glucose metabolism were categorized according to the WHO recommendation (CitationWHO 2006) as follows: normal glucose metabolism, IFG and/or IGT, and diabetes. The categorization was based either on self-reported diagnosis of diabetes with confirmed medication or on the result of an oral glucose tolerance test in this study. The patients with previously and newly diagnosed diabetes were analyzed both separately and by combining the groups. MetS was defined according to the consensus criteria (CitationAlberti et al. 2009), and its impact was also studied separately in patients with and without diabetes. BMI was analyzed both as a continuous variable and as a categorized variable. 3 groups were formed to maximize the statistical power as follows: normal or overweight (< 30), obese (30–34.9), and severely obese (≥ 35). In patients with diabetes, the effect of glucose control was evaluated by comparing patients with HbA1c < 6.5% and those with HbA1c ≥ 6.5% (CitationKowall and Rathmann 2013).

Associations between disorders of glucose metabolism, MetS, and obesity with a painful joint or persistent pain were first analyzed using cross-tabulation and the chi-squared test. Then, a binary logistic regression model with adjustment for age, sex, and operated joint was used to calculate respective odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Ethics and registration

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research plan was approved by the Ethics Board of Pirkanmaa Hospital District, Tampere, Finland (R12071; April 22, 2012). All the patients gave informed consent before participation. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier NCT01743313).

Results

49 patients (37%) had a painful joint. 18 of them (14% of the whole series) fulfilled the criteria of having persistent pain. The occurrence of persistent pain in 2 other patients was unclear because of missing answers to some of the 3 questions required for diagnosis.

Knee patients were more likely than hip patients to have a painful joint (46% vs. 24%; p = 0.01) and to suffer from persistent pain (20% vs. 4%; p = 0.007). Of 8 unicompartmental knee replacements in our material, 1 patient had persistent pain. According to the PainDetect questionnaire, the nature of pain was neuropathic in 2 of the 49 patients with a painful joint (4%). Both patients also fulfilled the criteria of having persistent pain.

Previously diagnosed diabetes was a significant risk factor for having persistent pain, but not for having a painful joint (). Other glucose metabolism disorders and MetS were not associated with a painful joint or persistent pain. A higher proportion of severely obese patients had a painful joint than patients with BMI < 30. The results concerning the effects of diabetes and severe obesity did not change when ASA score and BMI were added to the adjusted models: OR for persistent pain in patients with previously diagnosed diabetes was 20 (CI: 3–132) and OR for a painful joint in severely obese patients was 4 (CI: 1.3–14).

Table 3. Potential risk factors for a painful joint and persistent pain

The influence of obesity on the prevalence of a painful joint was similar in knee and hip patients. 14 of 39 non-obese knee patients, 11 of 26 obese knee patients, and 11 of 14 severely obese knee patients had a painful joint (p = 0.02), and the corresponding proportions of hip patients were 4/32, 6/15, and 3/7, respectively (p = 0.05). Also, a higher proportion of hip patients with MetS had a painful joint (12/36) than hip patients without MetS (1/18) (p = 0.04). Previously diagnosed diabetes was associated with persistent pain in hip patients (2/10 vs. 0/43; p = 0.03) but not in knee patients (3/8 vs. 13/71; p = 0.3). However, in a post-hoc analysis the statistical power in these analyses (with the probability of type 1-error set to 5%) turned out to be low for both hip and knee replacements: 47% and 83% for the effect of obesity on a painful joint (severely obese vs. non-obese), and 71% and 30% for the effect of diabetes on persistent pain, respectively.

In patients with diabetes, preoperative HbA1c was not associated with a painful joint (7/14 and 13/19 in patients with HbA1c < 6.5% and ≥ 6.5%, respectively; p = 0.3) or persistent pain (3/14 and 3/19; p = 1.0).

To study the influence of recovery time on the prevalence of pain, the patients were categorized into 3 groups based on the length of the follow-up time: < 15 months (55 patients), 15–21 months (51 patients), and > 21 months (28 patients). No statistically significant differences were found in these groups regarding diabetes, MetS, and different groups of BMI (data not shown). Similar proportions of patients in the different follow-up time groups had a painful joint (20/55, 21/51, and 8/27, respectively; p = 0.6). However, 10 of the 54 patients with the shortest follow-up time and 8 of the 51 patients with a follow-up time of 15–21 months reported having persistent pain, but none of the 27 patients with follow-up time of over 21 months reported having persistent pain (p = 0.04).

92% of the patients answered that they had less pain at rest and 89% had less pain when in motion relative to the situation preoperatively. Even so, 8% of the patients had no improvement in pain (or had more pain) at rest, and 11% had no improvement in pain (or had more pain) in motion. The poor pain relief was common in patients with previously diagnosed diabetes—of whom 3/16 had no improvement (or had more pain) at rest (6/92 among the others; p = 0.1) and 5/17 had no improvement (or had more pain) in motion (7/93 among the others; p = 0.02). MetS and obesity were not associated with poor pain relief (data not shown).

Discussion

This prospective study confirms earlier results (CitationNikolajsen et al. 2006, CitationPuolakka et al. 2010, CitationBeswick et al. 2012) indicating that pain in the operated joint is a common problem following primary hip and knee replacement, even after an uncomplicated postoperative course: one-third of patients had a painful joint and 14% had persistent pain. Our findings suggest that previously diagnosed diabetes is a risk factor for persistent pain whereas severe obesity is a risk factor for a painful joint 1–2 years after the operation. Other disorders of glucose metabolism and MetS were not associated with the prevalence of a painful joint or persistent pain. The prevalence of neuropathic pain was very low in our material. This supports the former findings that although neuropathic pain is common in other types of surgeries (CitationKehlet et al. 2006), the reason for persistent pain in joint replacement patients is something else—perhaps a low-grade inflammatory process with sensitization in the mechanisms of pain perception (CitationStürmer et al. 2004, CitationWylde et al. 2011).

Our main finding is that previously diagnosed diabetes is predictive of persistent pain in joint replacement patients with osteoarthritis. The difference appeared to be more pronounced in the hip replacement group, in which postoperative pain was otherwise less common than in the knee replacement group; but we acknowledge that this conclusion is based on relatively few patients. To our knowledge, there have been no earlier studies on the association between diabetes and persistent pain after joint replacement. Earlier, CitationGandhi et al. (2010) reported that diabetes was not an independent predictor of poor functional outcome or improvement in pain, measured at 1 year using WOMAC, although a trend could also be seen in that study. CitationJones et al. (2012) observed that recovery in terms of pain and function after total knee replacement was slower after 3 months to 3 years in patients with diabetes than in patients without diabetes. In both of these studies, the diagnoses of diabetes were based only on patients’ self-reported information or medical charts, whereas in our study patients without previously diagnosed diabetes had an oral glucose tolerance test in order to identify underlying disorders of glucose metabolism. Studies both in the general population and in joint replacement recipients have indicated that diabetes is underdiagnosed and that the real number of patients with diabetes is twice as much as originally believed (CitationMeding et al. 2007). Because of the careful diagnosis of diabetes in our study, we believe that the results reflect the actual situation more precisely and our findings that newly diagnosed diabetes, IFG, and IGT are not associated with a painful joint or persistent pain are reliable. Furthermore, unlike the earlier studies, we used the international classification of persistent pain as primary outcome.

Patients with diabetes are in a chronic systemic proinflammatory state (van CitationGreevenbroek et al. 2013). It has been shown that in patients with osteoarthritis, the degree of the patient’s inflammatory state is associated with the severity of preoperative pain (CitationStürmer et al. 2004). There is also a correlation between the severity of preoperative pain and the severity of postoperative pain (CitationKehlet et al. 2006), which is a risk factor for persistent pain (CitationPuolakka et al. 2010). Contradicting our expectations based on these earlier results, patients with diabetes had least pain, as measured using visual analog scale (VAS), preoperatively but still increased risk for persistent pain after surgery.

Other factors that could explain persistent pain in patients with diabetes are glucose control and diabetes-related complications, such as neuropathy. In the present study, we categorized diabetes into only 2 subgroups depending on whether it was diagnosed during the study or previously. This categorization did not allow us to examine the influence of poor long-term blood glucose equilibrium, or how long the previously diagnosed diabetic patient had suffered from diabetes. It is generally thought that blood HbA1c represents the long-term equilibrium of blood glucose levels in patients with diabetes. However, a single HbA1c measurement represents a patient’s blood glucose equilibrium from the previous 3 months only. Recent studies have shown that complications related to high blood glucose, such as neuropathy, need more time to develop and are rather related to long-term mean HbA1c or HbA1c variability (CitationKilpatrick 2012). No statistically significant associations between HbA1c and the pain outcomes were found in the present study either.

Interestingly, none of the patients had persistent pain after a follow-up time of 21 months. It may be that in joint replacement patients, the improvement in pain continues even after 1 year or more. Alternatively, it may be that patients with diabetes in particular require more time to reach full recovery. As there were only 2 patients with previously diagnosed diabetes in the group with the longest follow-up (which was also the smallest group), our study does not allow us to draw any conclusions on this issue. The definition of persistent pain (CitationInternational Association for the Study of Pain 1986) does not preclude the possibility that patients may recover from persistent postoperative pain. The prognosis of persistent pain is unknown, but it appears that the prevalence of pain decreases as time goes by. CitationBrander et al. (2003) found that the prevalence of substantial pain decreased from 23% after 3 months to 19% after 6 months, and 13% after 12 months following total knee replacement.

A higher proportion of severely obese patients had a painful joint than in the group of normal or overweight patients, whereas obesity was not associated with persistent pain. There is conflicting literature concerning the influence of obesity on the outcomes of joint replacement. According to some studies, obesity does not affect the outcomes while in others a negative effect could be seen (CitationWorkgroup of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons Evidence Based Committee 2013). CitationSingh and Lewallen (2010) reported that severe and morbid obesity are significant predictors of moderate-to-severe pain after total hip replacement at 2-year follow-up and 5-year follow-up. Investigations of satisfaction with joint replacement have not shown any statistically significant differences between obese and non-obese patients, yet morbid obesity (BMI > 40) appears to be a threshold for worse outcomes (CitationWorkgroup of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons Evidence Based Committee 2013). However, in our study BMI was statistically significantly associated with a painful joint even as a continuous variable.

Regarding the effect of MetS, CitationGandhi et al. (2010) reported that patient function and pain following joint replacement were negatively affected by the increasing number of metabolic abnormalities related to MetS. We did not find any associations between MetS and the prevalence of a painful joint, or persistent pain. The small sample size in our study may have biased our results, since closer examination of the number of individual components of MetS was not reasonable. On the other hand, in the study by Gandhi et al., no clinical examination was made and the diagnosis of MetS was based only on patients’ self-reported information about metabolic abnormalities. In earlier studies, poorly controlled MetS has been associated with perioperative surgical and medical complications after total joint replacement (Gonzales Della CitationValle et al. 2012, CitationZmistowski et al. 2013). We excluded patients with later joint replacements, but we did not analyze the other complications; nor did CitationGandhi et al. (2010), so we cannot preclude the possibility that complications could explain the conflicting results regarding pain.

The main strengths of the present study were its prospective nature and careful preoperative evaluation, with accurate detection of disturbances in glucose metabolism and other metabolic abnormalities. Persistent pain, our primary outcome measure, was defined in accordance with an international, generally accepted definition (CitationInternational Association for the Study of Pain 1986). A more recent definition has also been published (CitationMacrae and Davies 1999), in which the borderline for persistent pain is defined to be at least 2 months—instead of the 3 months used in the older definition. We decided to use the more strict definition with a 3-month limit, because it is reasonable to assume that 2 months is not enough in joint replacement patients. It has also been recommended by the IMMPACT consensus meeting (CitationDworkin et al. 2010) that a longer borderline should be used, at least in randomized trials. In previous studies, different definitions have been used for persistent pain (CitationMacrae 2008). Our institution is a high-volume center for joint replacement surgery, and the interventions and perioperative care were highly standardized and remained essentially unchanged during the study period. Most of the operations were performed by experienced joint replacement surgeons with high numbers of surgeries annually. Thus, variation in the treatment hardly biases our results. The response rate was rather good (82%). Patients who had revision surgery or another primary joint replacement in the study period were excluded, so the shortened recovery time of these patients would not bias our findings.

The study also had some weaknesses. Since its design was based on a research project on perioperative hyperglycemia, the number of patients was small from the point of view of analyzing the prevalence of and predictors of persistent pain. Exclusion of patients who had had later surgeries further reduced the number of patients available. Because of the small study population, we could not run a multifactorial analysis to examine whether diabetes was an independent risk factor for persistent pain. Furthermore, post-hoc power analysis indicated that our sample size was insufficient for appropriate joint-specific analysis. Such an analysis would have been important, because the etiology of persistent pain in joint replacement patients is not well known and it may be different after hip and knee replacement. The conclusions are based on a small absolute number of cases. In addition, we did not have information about the complications of diabetes, such as peripheral neuropathy, which might have been a relevant factor in explaining the results. Patients with diabetes may have more comorbidities such as depression and anxiety, and it cannot be ruled out that these comorbidities would explain the high prevalence of persistent pain in these patients. Acute postoperative pain is another factor that could have biased our results, since it is a risk factor for persistent pain, and we had no data on this. Because the study was started after the first surgeries in our series, there was some variation in follow-up times. However, even the patients with the shortest follow-up times should have had enough time to recover from surgery and early postoperative pain. Our materials do not represent a consecutive series of patients scheduled for surgery, but the patients were instead recruited in several (irregular) phases between 2009 and 2011.

Since pain in the operated joint was assessed with a postal questionnaire, we cannot be entirely sure that the patient’s answer concerned only the joint operated in this study. Selection bias is possible with patients who are planned for staged bilateral surgeries—and who were excluded from the present analysis—since they may have been older or have had more comorbidities than the patients included. Comorbidities of the patients may have also biased our results, since we were unable to take either individual comorbidities or the number of them into account. The ASA scores of the patients were, however, included in multifactorial linear regression models and they did not affect the results. Anxiety and depression are additional confounding factors (CitationVissers et al. 2012), the effects of which could not be taken into account retrospectively.

In conclusion, we found that previously diagnosed diabetes is a risk factor for persistent pain, and that severe obesity is a risk factor for a painful joint 1–2 years after primary hip or knee replacement. Patients and surgeons should know that these risk factors may reduce the benefits of joint replacement. Further research is needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying the association between disorders of glucose metabolism and postoperative pain.

EJ, TM, PN, and PP designed the study. TR collected the data, analyzed it, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and took care of its revisions. All the authors contributed to interpretation of the results and preparation of the manuscript.

We are grateful for the financial support of the Competitive Research Funding of Tampere University Hospital, Tampere, Finland (grants 9M026 and 9N020), which is government funding.

No competing interests declared.

- Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009; 120 (16): 1640–5.

- Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, Blom A, Dieppe P. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open 2012; 2 (1): e000435.

- Brander VA, Stulberg SD, Adams AD, et al. Predicting total knee replacement pain: a prospective, observational study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; (416): 27–36.

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Peirce-Sander S, et al. Research design considerations for confirmatory chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2010; 149 (2): 177–93.

- Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, Tölle TR. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2006; 22 (10): 1911–20.

- Gandhi R, Razak F, Davey JR, Mahomed NN. Metabolic syndrome and the functional outcomes of hip and knee arthroplasty. J Rheumatol 2010; 37 (9): 1917–22.

- Gonzales Della Valle A, Chiu YL, Ma Y, Mazumdar M, Memtsoudis SG. The metabolic syndrome in patients undergoing knee and hip arthroplasty: trends and in-hospital outcomes in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27(10): 1743–9.

- International Association for the Study of Pain. Classification of chronic pain: descriptions of chronic pain syndromes and definitions of pain terms. Pain Suppl 1986; 3; S1–226.

- Jones CA, Cox V, Jhangri GS, Suarez-Almazor ME. Delineating the impact of obesity and its relationship on recovery after total joint arthroplasties. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012; 20 (6): 511–8.

- Jämsen E, Nevalainen PI, Eskelinen A, Kalliovalkama J, Moilanen T. Risk factors for perioperative hyperglycemia in primary hip and knee replacements. Acta Orthop. Published online Nov 18, 2014.

- Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet 2006; 367 (9522): 1618–25.

- Kilpatrick ES. The rise and fall of HbA(1c) as a risk marker for diabetes complications. Diabetologia 2012; 55 (8): 2089–91.

- Kowall B, Rathmann W. HbA1c for diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Is there an optimal cut point to assess high risk of diabetes complications, and how well does the 6.5% cutoff perform? Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2013; 6: 477–91.

- Lundblad H, Kreicbergs A, Jansson KA. Prediction of persistent pain after total knee replacement for osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2008; 90 (2): 166–71.

- Macrae WA. Chronic post-surgical pain: 10 years on. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101 (1): 77–86.

- Macrae WA, Davies H T O. Chronic postsurgical pain. IASP Press 1999: 125–42.

- Meding JB, Klay M, Healy A, Ritter MA, Keating EM, Berend ME. The prescreening history and physical in elective total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2007; 22 (6 Suppl 2): 21–3.

- Nikolajsen L, Brandsborg B, Lucht U, Jensen TS, Kehlet H. Chronic pain following total hip arthroplasty: a nationwide questionnaire study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2006; 50 (4): 495–500.

- Puolakka PA, Rorarius MG, Roviola M, Puolakka TJ, Nordhausen K, Lindgren L. Persistent pain following knee arthroplasty. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2010; 27 (5): 455–60.

- Robertson F, Geddes J, Ridley D, McLeod G, Cheng K. Patients with Type 2 diabetes mellitus have a worse functional outcome post knee arthroplasty: a matched cohort study. Knee 2012; 19 (4): 286–9.

- Rolfson O, Dahlberg LE, Nilsson JA, Malchau H, Garellick G. Variables determining outcome in total hip replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009; 91 (2): 157–61.

- Singh JA, Lewallen DG. Predictors of pain and use of pain medications following primary Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA): 5,707 THAs at 2-years and 3,289 THAs at 5-years. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord 2010; 11: 90.

- Stürmer T, Brenner H, Koenig W, Günther KP. Severity and extent of ostearthritis and low grade systemic inflammation as assessed by high sensitivity C reactive protein. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63 (2): 200–5.

- van Greevenbroek MM, Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CD. Obesity-associated low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: causes and consequences. Neth J Med 2013; 71 (4): 174–87.

- Visser EJ. Chronic post-surgical pain: Epidemiology and clinical implications for acute pain management. Acute Pain 2006; 8 (2): 73–81.

- Vissers MM, Bussmann JB, Verhaar JA, Busschbach JJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Reijman M. Psychological factors affecting the outcome of total hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012; 41 (4): 576–88.

- WHO. Definition and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and intermediate hyperglycemia: report of a WHO/IDF consultation. World Health Organization (WHO) 2006.

- Workgroup of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons Evidence Based Committee. Obesity and total joint arthroplasty: a literature based review. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28: 714–721.

- Wylde V, Hewlett S, Learmonth ID, Dieppe P. Persistent pain after joint replacement: Prevalence, sensory qualities and postoperative determinants. Pain 2011; 152 (3): 566–72.

- Zmistowski B, Dizdarevic I, Jacovides CL, Radcliff KE, Mraovic B, Parvizi J. Patients with uncontrolled components of metabolic syndrome have increased risk of complications following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28(6): 904–7.