Abstract

Background and purpose — There is no consensus on the association between global femoral offset (FO) and outcome after total hip arthroplasty (THA). We assessed the association between FO and patients’ reported hip function, quality of life, and abductor muscle strength.

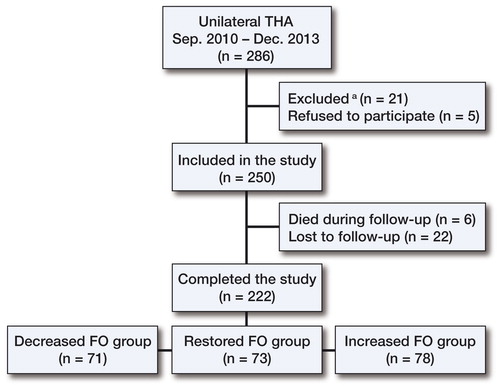

Patients and methods — We included 250 patients with unilateral hip osteoarthritis who underwent a THA. Before the operation, the patient’s reported hip function was evaluated with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index and quality of life was evaluated with EQ-5D. At 1-year follow-up, the same scores and also hip abductor muscle strength were measured. 222 patients were available for follow-up. These patients were divided into 3 groups according to the postoperative global FO of the operated hip compared to the contralateral hip, as measured on plain radiographs: the decreased FO group (more than 5 mm reduction), the restored FO group (within 5 mm restoration), and the increased FO group (more than 5 mm increment).

Results — All 3 groups improved (p < 0.001). The crude results showed that the decreased FO group had a worse WOMAC index, less abductor muscle strength, and more use of walking aids. When we adjusted these results with possible confounding factors, only global FO reduction was statistically significantly associated with reduced abductor muscle strength. The incidence of residual hip pain and analgesics use was similar in the 3 groups.

Interpretation — A reduction in global FO of more than 5 mm after THA appears to have a negative association with abductor muscle strength of the operated hip, and should therefore be avoided.

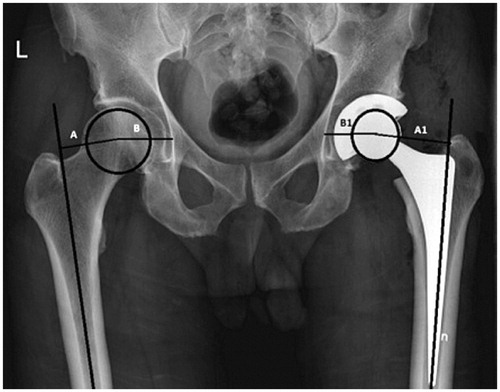

Surgeons aim to position the stem and cup in THA in such a manner that mechanical forces and range of motion of the operated hip are restored. The femoral offset (FO) is one of the important perioperative parameters in THA. It is commonly measured as the radiological distance between the center of rotation of the femoral head and the long axis of the femur (Lecerf et al. Citation2009). However, this measurement does not take into account of the changes caused by different positioning of the acetabular cup. The latter is usually measured separately as the distance between the center of the femoral head and a perpendicular line passing through the medial edge of the ispsilateral acetabular teardrop. This is referred to as the cup offset (Loughead et al. Citation2005). By adding the cup offset to the FO, the global FO is obtained (Kjellberg et al. Citation2009, Lecerf et al. Citation2009, Dastane et al. Citation2011).

Inadequate restoration of FO after THA may cause implant instability, hip impingement, increased joint reaction forces, increased polyethylene wear, loosening, and inability to maintain a level pelvis throughout the gait cycle (McGrory et al. Citation1995, Sakalkale et al. Citation2001, Asayama et al. Citation2005, Malik et al. Citation2007, Lecerf et al. Citation2009, Little et al. Citation2009, Sariali et al. Citation2009). On the other hand, increasing FO has been hypothesized to improve the hip lever arm and subsequently the range of motion and abductor muscle strength, and to reduce prosthetic instability and polyethylene wear (McGrory et al. Citation1995, Yamaguchi et al. 2004, Asayama et al. Citation2005, Marx et al. Citation2005, Malik et al. Citation2007, Sariali et al. Citation2009, Kiyama et al. Citation2010). Unfortunately, the published data on this issue has some shortcomings—such as inadequate sample size (Yamaguchi et al. 2004, Asayama et al. Citation2005), retrospective design (McGrory et al. Citation1995, Asayama et al. Citation2005, Marx et al. Citation2005, Kiyama et al. Citation2010, Cassidy et al. Citation2012, Liebs et al. Citation2014), heterogeneous groups (McGrory et al. Citation1995, Asayama et al. Citation2005, Kiyama et al. Citation2010, Cassidy et al. Citation2012), and inadequate radiological measurements of FO (Asayama et al. Citation2005, Cassidy et al. Citation2012, Liebs et al. Citation2014). Further well-conducted studies of the association between global FO and both functional outcome and abductor muscle strength are needed.

We therefore investigated the association between changes in global FO after THA and patients’ reported hip function, quality of life, and abductor muscle strength. Based on the observations made in previous studies (Cassidy et al. Citation2012, Sariali et al. Citation2014), we hypothesized that reduction of global FO by more than 5 mm on the operated hip, relative to the contralateral side, would be associated with reduced functional outcome.

Patients and methods

This prospective cohort study was conducted at Sundsvall Teaching Hospital, Sweden, between September 2010 and December 2013. All patients with unilateral primary osteoarthritis (OA) treated with THA were considered for inclusion. Patients with secondary OA or with previous spinal, pelvic, or lower limb injuries or fractures were excluded.

The primary outcome measure was the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index, which measures functional outcome (Bellamy et al. Citation1988). The secondary outcome measures were: (1) the EQ-5D, which measures quality of life over 5 dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression (Dawson et al. Citation2001), (2) the patient’s rating of his or her health status using a visual analog scale (EQ VAS), and (3) hip joint abductor muscle strength measured using an electronic dynamometer.

The patients were assessed preoperatively and at follow-up with the self-administered WOMAC and EQ-5D questionnaires (including a visual analog scale for health status).

1 of 10 specialist orthopedic surgeons, or an assistant directly under their supervision, performed the operations using either a cemented Lubinus SP II system (Link, Germany) or cementless Spotorno (CLS) stem and Triology cup (Zimmer). The Lubinus stem we used has a center collum diaphyseal (CCD) angle (126°), a 32-mm head, and 3 neck lengths (47.5 mm, 51.5 mm, and 55 mm) while the CLS stem has a CCD angle (125°), a 32-mm head, and 4 neck lengths (−4, 0, 4, and 8 mm). The posterolateral approach was used in all operations. Preoperative radiological templating using the Mdesk system (RSA Biomedical, Umeå, Sweden) was performed in most cases. No further intraoperative assessment of FO was done. The patients were mobilized on the first postoperative day, with full weight bearing allowed and following the same postoperative rehabilitation program.

Measurement of global femoral offset

Global FO was measured in each patient at most 3 months before the THA and on the second postoperative day, using a standardized protocol. The anteroposterior (AP) hip radiograph was taken with the patient supine and both legs internally rotated 15 degrees, and with the X-ray beam centered on the pubic symphysis with a film focus distance of 115 cm (Frank et al. Citation2007).

The global FO was measured by adding the distance between the longitudinal axis of the femur and the center of the femoral head to the distance from the center of the femoral head to a perpendicular line passing through the medial edge of the ipsilateral teardrop point of the pelvis (). The measurement was repeated bilaterally to compare the global FO of the operated side to that of the nonoperated side. A positive value was used when the FO of the operated hip was greater than that of the contralateral side, while a negative value indicated the opposite. Measurements were calibrated to a 30-mm radiopaque standardized metal sphere or prosthetic head (32 mm) to assess the degree of magnification. A 1-mm precision scale was used. 1 independent investigator (SaSM) performed the radiological measurements to ensure objectivity.

Figure 1. The global FO was measured by addition of the distance between the longitudinal axis of the femur and the center of the femoral head (A1) and the distance from the center of the femoral head to a perpendicular line passing through the medial edge of the ipsilateral teardrop point of the pelvis (B1). The measurement was repeated bilaterally to compare the global FO of the operated side (A1 + B1) to that of the unoperated hip (A + B).

Depending on the postoperative measurement, the patients were divided into 3 groups: (1) the decreased FO group, where the global FO of the operated side was reduced by more than 5 mm compared to the contralateral side, (2) the restored FO group, where the global FO of the operated side was restored within 5 mm compared to the contralateral side, and (3) the increased FO group, where the global FO of the operated side was increased by more than 5 mm compared to the contralateral side.

Measurement of outcome scores

Patients were followed up at 12–15 months postoperatively with the self-administered WOMAC form and EQ-5D questionnaire in addition to a clinical assessment. The patients completed an additional questionnaire enquiring about any residual problems: the use of walking aids (yes/no), residual pain around the operated hip (yes/no), or use of analgesics for hip pain (yes/no). Measurement of abductor muscle strength was done during the clinical assessment. Dislocation events were also recorded.

Measurement of abductor muscle strength

The same observer (SaSM) conducted isometric abductor muscle strength measurements in all patients at the outpatient department according to Asayama et al. (Citation2005). Before measurement, information about the test was given to the patients to allow them to become familiar with it. While the patient was in supine position with straight legs on a padded table, the pelvis was immobilized with a band across the iliac spines. An electronic dynamometer (MAV Prüftechnik, Berlin, Germany) was used. The pad of the compression arm was centered at the lateral aspect of the thigh, just below the midpoint between the greater trochanter and the knee joint. The patient was then asked to maximally abduct the thigh against the pad. The unoperated side was tested first. We performed 2 trials for each side with a 1 min of rest inbetween. We documented the higher of the 2 strength measurements for each side and then calculated the percentage for the operated side in relation to the contralateral side.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS for Windows version 20.0. To calculate the sample size required, a priori power analysis was performed using G*Power software (Faul et al. Citation2009); this was based on comparing the means of the primary outcome WOMAC index of each group. With a power of 0.80 and a significance level (alpha) of 0.05, a minimum of 65 patients would be needed in each group to detect a clinically significant 7 to 10-point difference in WOMAC index (SD 20) between the 3 groups. Before using parametric tests, data were checked for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Demographic data are presented as mean and SD. A 2-tailed paired t-test was used to test hypotheses about change in preoperative and postoperative outcome scores.

Based on the null hypothesis that an FO reduction of more than 5 mm would not be associated with a worse postoperative WOMAC index (as a single outcome), we used ANOVA to test this. Separate ANOVAs were also used to test any association between global FO and any of the following: WOMAC pain, WOMAC stiffness, WOMAC physical activity, EQ-5D, health status, and abductor muscle strength. Tukey’s post-hoc tests were then used to compare 2 groups at a time.

The comparison of residual problems of using a walking aid, residual pain around the operated hip, use of analgesics, and dislocation in the 3 groups was evaluated with Fisher’s exact test. The crude results of these comparisons were further adjusted for possible confounding factors when statistically significant associations were found, in order to determine whether or not these associations were causal. We chose, for example, age, sex, and preoperative WOMAC index as a priori selection for possible confounding factors since we expected that these variables would relate both to the exposure and to the outcome, and that they would not be in the causal pathway between the potential risk factor and the outcome (Shrier and Platt Citation2008). In all tests, any p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Ethics and registration

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the regional ethics committee of Umeå University (no. 07-052M and no. 12-287-32M). Informed consent was obtained from all patients. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (identifier NCT NCT02399670).

Results

286 consecutive patients were eligible for inclusion in the study. 21 patients were excluded because they had previous trauma/pain in the contralateral hip or spine and 15 patients refused to participate in the study, leaving 250 patients. At the end of the study, a complete set of results for 222 patients (78%) was available (115 males) (). A cemented prosthesis was used in 176 patients (79%) and a non-cemented prosthesis in 46 patients.

There were 71 patients (32%; mean age 71 years; 33 females) in the decreased FO group where the operated hip had more than a 5-mm reduction in FO compared to the contralateral side (mean −12.8 mm). There were 73 patients (33%; mean age 68 years; 35 females) in the restored FO group, where the operated hip had FO restored to within 5 mm compared to the contralateral side (mean −0.4 mm). Finally, there were 78 patients (35%; mean age 65 years; 39 females) in the increased FO group, where the operated hip had more than a 5-mm increment in FO compared to the contralateral side (mean 12 mm).

Comparisons of the preoperative WOMAC indices, EQ-5D and health status among the 3 groups showed no statistically significant differences (). All 3 groups had significant improvements (p < 0.001) in postoperative WOMAC index, EQ-5D, and health status ().

Table 1. Comparison of WOMAC index, EQ-5D, and health status in the 3 groups preoperatively and at 12–15 months. Values are mean (SD)

The crude results of comparing the postoperative WOMAC indices, EQ-5D, health status, and abductor muscle strength among the 3 groups () showed a statistically significant difference in WOMAC index (mainly attributable to a lower physical activity score) and abductor muscle strength. Further analysis with Tukey’s post-hoc test revealed that the difference was between the decreased FO group and the 2 other groups (p = 0.05). Analysis of the “residual problems” questionnaire and examination for remaining hip problems showed that the use of walking aids was more common in the decreased FO group than in the restored FO and increased FO groups (32% vs. 21% and 15%; p = 0.04) while the incidence of residual hip pain, use of analgesics for hip pain, and postoperative dislocation in the 3 groups was comparable ().

Table 2. The crude results of comparing postoperative WOMAC index (primary outcome) and other parameters among the 3 groups. The p-values were measured with ANOVA and Fisher’s exact test. Values are mean (SD)

Table 3. The adjusted results for factors associated with postoperative WOMAC index, abductor muscle strength, and use of walking aids

When the above-mentioned crude results for comparing the postoperative WOMAC indices, abductor muscle strength, and use of walking aids in the 3 groups were adjusted for possible confounding factors (e.g. gender, age, and preoperative WOMAC index), reduction in global FO was only associated with abductor muscle strength ().

Discussion

Our crude results showed that a reduced postoperative global FO of more than 5 mm compared to the contralateral hip was associated with less improvement in functional outcome, weaker hip abductor muscles, and more use of a walking aids. On the other hand, restoration and increment of global FO gave better results that were comparable (). When these results were adjusted for possible confounding factors, reduced global FO postoperatively was only associated with weaker hip abductor muscles. Increasing age and female sex were associated with less improvement in functional outcome and more use of a walking aid (). In all 3 groups (decreased, restored, and increased global FO), the improvement in all parameters after THA was statistically and clinically significant compared to preoperatively ().

Assessment of global FO is an important part of perioperative THA planning. Despite the fact that measurement of global FO by computed tomography is more accurate than with plain radiographs (Kjellberg et al. Citation2009, Lecerf et al. Citation2009, Sariali et al. Citation2009, Pasquier et al. Citation2010), the associated high cost, radiation exposure, and limited availability make its routine use impractical and it is limited to selected cases. Thus, plain radiographs are normally used. The validity and reliability of different plain radiographic global FO measurements are well documented (Kjellberg et al Citation2009, Patel et al. Citation2011, Merle et al. Citation2013, Mahmood et al. Citation2015). In this study, we measured the global FO as the sum of femoral offset and cup offset. This combined measurement takes account of the changes caused by implant design and the positioning of the stem within the femoral canal as well as the changes in the acetabular center of rotation caused by cup implantation (Loughead et al. Citation2005, Kurtz et al. Citation2010). The latter was found to be an essential factor in restoring the global FO in THA (Dastane et al. Citation2011) and to affect the incidence of bony impingement more than the stem offset (Kurtz et al. Citation2010). We chose the 5-mm cutoff to divide our patients into 3 groups, because previous reports (Cassidy et al. Citation2012, Sariali et al. Citation2014) suggested that this cutoff value affects outcome.

All global FO groups showed a statistically and clinically significant improvement in WOMAC index, EQ-5D, and health status. The crude results showed an association between the decreased global FO group and worse WOMAC index and more use of walking aids compared to the restored and increased FO groups. Further analysis showed that this difference was mainly in the WOMAC physical function subscore. However, when we adjusted these results for age, sex, and preoperative WOMAC index, these associations were no longer apparent. On the other hand, the decreased global FO group had weaker hip abductor muscle compared to the other 2 groups, both in the crude results and the adjusted results. This is most probably due to shortening of the lever arm of the operated hip, with subsequent loss of abductor muscle tension and power. These findings are in agreement with the results of Cassidy et al. (Citation2012), who found a worse score for the WOMAC physical activity subscale in their decreased global FO group and speculated that this was the result of abductor muscle weakness. Other studies have shown positive correlations between FO restoration and both abductor muscle strength and hip range of motion (McGrory et al. Citation1995, Yamaguchi et al. 2004, Asayama et al. Citation2005, Kiyama et al. Citation2010). In contrast, Liebs et al. (Citation2014) found that decreasing FO by more than 5 mm was associated with the best improvement in score for the WOMAC pain subscale. The authors did not mention whether all the patients included had primary osteoarthritis and whether the same surgical approach was used, and no explanation was given for their results. Sariali et al. (Citation2014) studied the effect of modification of global FO after THA on gait. They found that a 6- to 12-mm decrease in FO after THA altered the gait, with lower swing speed and reduced range of motion at the knee when walking.

The changes in global FO had no effect on quality of life and health status in our study. This agrees with the findings of Liebs et al. (Citation2014) who used the SF-36 health survey form and Cassidy et al. (Citation2012) who used the SF-12 health survey form.

The risk of dislocation was similar in the 3 groups. This means that decreasing global FO did not appear to compromise prosthetic stability. Indeed, this could indicate the importance of other parameters such as patient compliance, implant positioning, and leg length restoration for prosthetic stability.

Surgeons aim for proper restoration of global FO in THA. Few methods have been recommended to help reach this goal. Preoperative templating allows the surgeon to evaluate several vital parameters such as hip joint bone stock and acetabular and femoral component size and position to achieve proper leg length and global FO. Furthermore, intraoperative devices can also be used to judge the soft tissue balance and therefore avoid under- and over-tensioning (Charles et al. Citation2005, Barbier et al. Citation2012). Other modalities for intraoperative FO include fluoroscopy and computer-assisted navigation (Renkawitz et al. Citation2014, Webere et al. 2014). These technique have generally been reported to have good to excellent accuracy in spite of the influence of the surgeon’s experience on the results achieved.

Our study had some limitations. The measurement of global FO was done on plain radiographs, which could have underestimated the actual changes compared to the more accurate CT scan. However, this underestimation should have been negligible, as we calculated the difference between the operated side and the contralateral side. Furthermore, plain radiography is the commonly used method for measurement of global FO after THA in clinical practice, owing to its availability and acceptable radiation exposure. Another limitation is the ceiling effect of the WOMAC index and EQ-5D questionnaire (Marx et al. Citation2005, Garbuz et al. Citation2006), which could mask some of the difference between patients with good outcome. The strengths of our study were the prospective cohort design with sufficient sample size and the homogenous groups of patients. We included only patients with unilateral OA, which would reduce the risk of radiological and clinical measurement bias caused by the effect of possible OA changes in the contralateral hip. We also had preoperative hip function and quality of life data available. The evaluation of hip abductor muscle strength was done by a valid method using an electronic dynamometer. The outcome instruments used (WOMAC index and EQ-5D questionnaire) have good validity and will allow comparison of our results with other studies.

In summary, a reduction in global FO of more than 5 mm after THA appears to have negative association with abductor muscle strength of the operated hip, and should therefore be avoided. Restoration and increment of global FO gave better results that were comparable, with no negative effects.

SaSM collected the data, reviewed the literature, and wrote the manuscript. SeSM assisted in literature review and wrote the manuscript. SC and PW reviewed the manuscript. ASSN initiated and designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

No competing interests declared.

- Asayama I, Chammongkich S, Simpson K J, Kinsey T L, Mahoney O M. Reconstructed hip joint position and abductor muscle strength after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2005; 20: 414-20.

- Barbier O, Ollat D, Versier G. Interest of an intraoperative limb length and offset measurement device in total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2012; 98(4): 398-404.

- Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith C H, Campbell J, Stitt L W. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patient with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 1988; 15(12): 1833-40.

- Cassidy K A, Noticewala MS, Macaulay W, Lee J H, Geller J A. Effect of femoral offset on pain and function after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27(10): 1863–9.

- Charles M N, Bourne R B, Davey J R, Greenwald A S, Morrey B F, Rorabeck C H. Soft-tissue balancing of the hip: the role of femoral offset restoration. Instr Course Lect 2005; 54: 131-41.

- Dastane M, Dorr L D, Tarwala R, Wan Z. Hip offset in total hip arthroplasty: quantitative measurement with navigation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011; 469(2): 429-36.

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Frost S, Gundle R, McLardy-Smith P, Murray D. Evidence for the validity of a patient-based instrument for assessment of outcome after revision hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83(8): 1125-9.

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang A-G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods 2009; 41: 1149-60.

- Frank E D, Long B W, Smith B J. 329 Merrill’s atlas of radiographic positioning & procedures, 11th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby\Elsevier; 2007.

- Garbuz D S, Xu M, Sayre E C. Patients’ outcome after total hip arthroplasty: a comparison between the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities index and the Oxford 12-item hip score. J Arthroplasty 2006; 21(7): 998-1004.

- Kjellberg M, Englund E, Sayed-Noor A S. A new radiographic method of measuring femoral offset. The Sundsvall method. Hip Int 2009; 19(4): 377-81.

- Kiyama T, Natio M, Shinoda T, Maeyama A. Hip abductor strengths after total hip arthroplasty via the lateral and posterolateral approaches. J Arthroplasty 2010; 25(1): 76-80.

- Kurtz W B, Ecker T M, Reichmann W M, Murphy S B. Factors affecting bony impingement in hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2010; 25: 624–34.

- Lecerf G, Fessy M H, Philippot R, Massin P, Giraud F, Flecher X, Girard J, Mertl P, Marchetti E, Stindel E. Femoral offset: anatomical concept, definition, assessment, implications for preoperative templating and hip arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2009; 95: 210–9.

- Liebs T R, Nasser L, Herzberg W, Rüther W, Hassenpflug J. The influence of femoral offset on health-related quality of life after total hip replacement. Bone Joint J 2014; 96-B(1): 36-42.

- Little N J, Busch C A, Gallagher J A, Rorabeck C H, Bourne R B. Acetabular polyethylene wear and acetabular inclination and femoral offset. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467: 2895-900.

- Loughead J M, Chesney D, Holland J P, McCaskie A W. Comparison of offset in Birmingham hip resurfacing and hybrid total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005; 87(2): 163-6.

- Mahmood S S, Al-Amir B, Mukka S S, Baea S S, Sayed-Noor A S. Validity, reliability and reproducibility of plain radiographic measurements after total hip arthroplasty. Skeletal Radiol 2015; 44(3): 345-51.

- Malik A, Maheshwari A, Dorr L D. Impingement with total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89(8): 1932-42.

- Marx R G, Jones E C, Atwan N C. Measuring improvement following total hip and knee arthroplasty using patient-based measures of outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87(9): 1999-2005.

- McGrory B J, Morrey B F, Cahalan T D, An K N, Cabanela M E. Effect of femoral offset on range of motion and abductormuscle strength after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995; 77: 865-9.

- Merle C, Waldstein W, Pegg E C, Streit M R, Gotterbarm T, Aldinger P R, Murray D W, Gill H S. Prediction of three-dimensional femoral offset from AP pelvis radiographs in primary hip osteoarthritis. Eur J Radiol 2013; 82(8): 1278-85.

- Pasquier G, Ducharne G, Ali E S, Giraud F, Mouttet A, Durante E. Total hip arthroplasty offset measurement: is C T scan the most accurate option? Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2010; 96(4): 367-75.

- Patel S R, Toms A P, Rehman J M, Wimhurst J. A reliability study of measurement tools available on standard picture archiving and communication system workstations for the evaluation of hip radiographs following arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 21(93): 1712-9.

- Renkawitz T, Sendtner E, Schuster T, Weber M, Grifka J, Woerner M. Femoral pinless length and offset measurements during computer-assisted, minimally invasive total hiparthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29(5): 1021-5.

- Sakalkale D P, Sharkey P F, Eng K, Hozack W J, Rothman R H. Effect of femoral component offset on polyethylene wear in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001; 388: 125-34.

- Sariali E, Mouttet A, Pasquier G, Durante E, Catone Y. Three-dimensional hip anatomy in osteoarthritis. Analysis of the femoral offset. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24(6): 990-7.

- Sariali E, Klouche S, Mouttet A, Pascal-Moussellard H. The effect of femoral offset modification on gait after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2014; 85(2): 123-7.

- Shrier I, Platt R W. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 70.