Abstract

Background and purpose — There are no international guidelines to define adverse reaction to metal debris (ARMD). Muscle fatty atrophy has been reported to be common in patients with failing metal-on-metal (MoM) hip replacements. We assessed whether gluteal muscle fatty atrophy is associated with elevated blood metal ion levels and pseudotumors.

Patients and methods — 263 consecutive patients with unilateral ASR XL total hip replacement using a posterior approach and with an unoperated contralateral hip were included in the study. All patients had undergone a standard screening program at our institution, including MRI and blood metal ion measurement. Muscle fatty atrophy was graded as being absent, mild, moderate, or severe in each of the gluteal muscles.

Results — The prevalance of moderate-to-severe gluteal muscle atrophy was low (12% for gluteus minimus, 10% for gluteus medius, and 2% for gluteus maximus). Muscle atrophy was neither associated with elevated blood metal ion levels (> 5 ppb) nor with the presence of a clear (solid- or mixed-type) pseudotumor seen in MRI. A combination of moderate-to-severe atrophy in MRI, elevated blood metal ion levels, and MRI-confirmed mixed or solid pseudotumor was rare. Multivariable regression revealed that “preoperative diagnosis other than osteoarthrosis” was the strongest predictor of the presence of fatty atrophy.

Interpretation — Gluteal muscle atrophy may be a clinically significant finding with influence on hip muscle strength in patients with MoM hip replacement. However, our results suggest that gluteal muscle atrophy seen in MRI is not associated with either the presence or severity of ARMD, at least not in patients who have been operated on using the posterior approach.

Adverse reaction to metal debris (ARMD) continues to be a major reason for reoperation in patients with metal-on-metal (MoM) hip replacement (Bolland et al. Citation2011, Bisschop et al. Citation2013, Reito et al. Citation2013, Lainiala et al. Citation2014b) . There are, however, no international guidelines on how to define ARMD; nor is there any consensus on indications for revision surgery in patients with suspected ARMD. Based on the current literature, it is certain that ARMD cannot be classified as one single entity; a variety of soft tissue abnormalities may occur (Browne et al. Citation2010, Chang et al. Citation2012, Lainiala et al. Citation2014a, Nawabi et al. Citation2014). The most important finding associated with failing MoM hips is the presence of pseudotumor (PT), which may be of cystic, solid, or mixed type (Hart et al. Citation2012). However, cystic lesions resembling pseudotumors have also been found in patients with non-MoM bearings, and the clinical significance of such lesions in unclear (Carli et al. Citation2011, Mistry et al. Citation2011). Elevated whole-blood (WB) metal ion levels are also commonly seen in patients with suspected ARMD (Bisschop et al. Citation2013). Perioperative ARMD-related findings include soft tissue necrosis, fluid collections, joint effusion, osteolysis, and metallosis (Browne et al. Citation2010, Nishii et al. Citation2012, Lainiala et al. Citation2014a).

Moderate-to-severe muscle atrophy, either in gluteal or external rotator (ER) muscles, has been reported in most patients with unexplained pain and suspected ARMD who were operated on with MoM hip resurfacing (Toms et al. Citation2008, Sabah et al. Citation2011, Wynn-Jones et al. Citation2011, Nawabi et al. Citation2014, Berber et al. Citation2015). A recent study has suggested that progressive muscle atrophy is present in a substantial proportion of patients with MoM hip replacements (Berber et al. Citation2015). Pseudotumor with gluteal muscle atrophy or tendon avulsion has been proposed to be one subtype of failure in MoM hips (Liddle et al. Citation2013). It is well known that ER muscle atrophy is very common in patients in whom the posterior surgical approach has been used. Whether or not muscle atrophy is specifically associated with ARMD is poorly understood and still a controversial issue. Furthermore, the natural history of ARMD has not been established, so there is a need to determine whether muscle atrophy is associated with development of ARMD.

The purpose of this study was (1) to determine the prevalance of gluteal muscle atrophy, (2) to assess the association between gluteal muscle atrophy with elevated blood metal ion levels and the presence of pseudotumor in MRI, and (3) to investigate the factors associated with the presence of gluteal muscle atrophy in postoperative MRI in patients with a unilateral ASR XL total hip replacement.

Patients and methods

Patient population and screening

537 ASR XL MoM total hip arthroplasties (DePuy, Warsaw, IN) were performed in 471 patients at our institution between March 2004 and December 2009. The cementless proximally porous-coated Summit stem (DePuy) was used in 380 of these operations (70%) and the cementless hydroxyapatite coated Corail stem (DePuy) was used in 109 (20%). The S-ROM stem (DePuy) was implanted in 42 operations (8%). All operations were performed by—or under the direct supervision of—6 experienced hip surgeons with a posterior approach, and according to a standard protocol used at our institution.

DePuy Orthopaedics voluntarily recalled their ASR MoM hip system in August 2010. After the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency announced a medical device alert regarding ASR hip arthroplasty implants in September 2010, we established a mass screening program to identify possible articulation-related complications in patients who had received an ASR XL prosthesis during hip arthroplasty at our institution. All the patients who attended screening received an Oxford hip score questionnaire, underwent a thorough clinical examination (including the Harris hip score) at our outpatient clinic, and were referred for measurement of WB cobalt and chromium levels. In addition, AP and lateral radiographs of the hip and an AP pelvic radiograph were taken before each visit. All patients were referred for magnetic artifact reduction sequence (MARS) MRI. If MARS MRI was contraindicated or could not be done because of patient-related factors (such as claustrophobia), the patient underwent ultrasonography (US) of the affected hip.

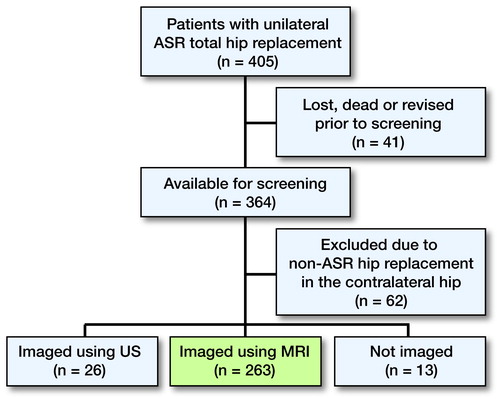

Study population ()

We identified all patients with a unilateral ASR XL THR. In order to have as robust an analysis as possible, we tried to avoid violating the assumption of independent observations by only including unilateral patients. There were 405 patients with unilateral ASR THR. Of these patients, 364 (89%) were alive, had not undergone any revision operation, and agreed to participate in the screening program. 62 patients (all non-ASR) were excluded due to hip replacement in the contralateral hip. There were 2 main reasons for this exclusion. Firstly, muscle atrophy between the operated hip and the nonoperated hip is compared in an optimal way. Secondly, if one excludes patients with MoM hip replacement in the contralateral hip also, the regression analysis is more robust regarding blood metal ion analysis. Of the remaining 302 patients, 39 were excluded because 26 of them had undergone only US of the affected hip and 13 had not been imaged at all because of comorbidities. Thus, 263 patients had undergone MRI as part of our screening program, and all of them gave informed consent to participate in the study. Patients who underwent US instead of MRI and those without imaging did not differ statistically significantly from patients who had undergone an MRI regarding median femoral diameter and WB metal ion levels (all p > 0.05).

MRI protocol

MRI was performed with 2 1.5-T machines (Siemens Magnetom Avanto 1.5 T; Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany; and GE Signa HD 1.5 T; General Electric Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). All examinations were done with coronal and axial T1-weighted fast spin echo and coronal, axial, and sagittal short tau inversion recovery. Specifications of MRI protocols are provided in Supplementary data.

MRI assessment

MRI findings regarding pseudotumor (PT) were categorized using the Imperial College classification (Hart et al. Citation2012). In this classification, type-1 PT means a pseudotumor with thin walls and fluid-like core signal. Class 2A indicates a PT with thick or irregular walls and a fluid-like core signal. Class 2B PT refers to PT with thick or irregular walls and an atypical fluid core. Class 3 indicates a solid PT. MRI scans were analyzed by a musculoskeletal radiologist (PE). Muscle atrophy was assessed as a decrease in volume and the appearance of fatty change relative to the contralateral, nonoperated side. The classification described by Bal and Lowe (Citation2008) was used. In their system, atrophy is graded from 0 to 3. Grade 0 indicates normal muscle structure, grade 1 indicates atrophy not exceeding 30% in size, grade 2 indicates 30% to 70% fatty change along with decrease in muscle size, and grade 3 indicates more than 70% fatty change along with more than an 80% decrease in muscle size.

Metal ion analysis

All patients attending the screening program had blood samples taken from the antecubital vein using a 21-gauge needle connected to a Vacutainer system and trace element blood tubes containing sodium EDTA. The first 10 mL of blood was used for other laboratory tests such as C-reactive protein (CRP) and measurement of erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). The second 10 mL was used for cobalt and chromium analysis. In the Finnish Institute for Occupational Health, standard operating procedures have been established for Co and Cr measurement using dynamic reaction cell inductively coupled plasma (quadripole) mass spectrometry (ICPMS) (Agilentin 7500cx; Agilentin, Santa Clara, CA). WB metal ion levels were considered to be elevated if either Cr or Co exceeded 5 ppb (Hart et al. Citation2011).

Statistics

Continuous, normally distributed variables were compared using Student’s t-test. Non-parametric variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare distributions of non-parametric variables between 3 groups of atrophy grade. The chi-square test was used to compare distributions. A generalized linear model with a logarithmic link function and binomial distribution was used to assess risk factors for presence of gluteal muscle atrophy. For the purposes of log-binomial regression, 4 covariates were included in the analysis: sex, age, pseudotumor classification, and preoperative diagnosis. Directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) were used to assess the possible bias introduced by variable selection (see Supplementary data) (Shrier and Platt Citation2008). When gluteal muscle atrophy was treated as outcome variable, pseudotumor as exposure, and other variables as covariates, the DAG approach confirmed that minimal bias had been introduced with our set of covariates. If WB metal ion levels were treated as exposure, the DAG approach suggested that our set of covariates would yield too biased estimate for the total causal effect of WB metal ion on outcome levels since pseudotumors were assumed to be caused by elevated metal ion levels. The DAG approach states that covariate (pseudotumor) should not be descendant of exposure (metal ion levels). WB metal ion levels were therefore not included as covariate. For age, a cut-off value of 50 years was used. Pseudotumor classification had 3 categories: no PT, cystic PT (class 1), and mixed-type or solid-type PT (classes 2A, 2B, and 3). Preoperative diagnosis had 2 categories: osteoarthritis (OA) and other. In order to achieve the primary aims of our study, multivariable log-binomial regression analysis was performed to analyze the factors associated with the presence of gluteal muscle atrophy by MRI of the operated hip. Clinically, there is no relevant baseline assumption regarding the degree of atrophy and in which muscle, to use as an endpoint. We therefore addressed this issue from a statistical standpoint. The regression model used should be as stable as possible, i.e. the variation in the coefficients should be sufficiently small. This is achieved by using a sufficient number of endpoints in the regression. With categorized covariates, it is essential to have all possible combinations of covariates and endpoints, i.e. both sexes must have at least 1 case with muscle atrophy used as outcome variable (endpoint). This criterion must be met in order to have a stable logistic model. Each covariate was therefore cross-tabulated against each possible outcome variable (contingency table). There were 9 possible outcome variables, i.e. endpoints: mild-to-severe atrophy, moderate-to-severe atrophy, or severe atrophy in either g. minimus, g. medius, or g. maximus. If there were no missing data, i.e. no cells with zero counts, this outcome variable was used in the regression analysis. The first step of logistic regression involves interpretation of a likelihood ratio (LR) test comparing a 0-model with the model produced after including all 4 covariates. The LR tells how well the independent variables affect the outcome variable. If the p-value for the overall model-fit statistic (LR) is significant (< 0.05), then there is evidence that at least 1 of the independent variables contributes to the prediction of the outcome. Estimates of prevalence ratios (PRs) were obtained and interpreted only if the overall model fit was significant. 95% Wald confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for each PR. Significance was assumed at p-values ≤ 0.05. Analyses were done using the R statistical package v3.0.2 (R foundation, Vienna, Austria).

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the ethics committee of our hospital district (approval no. R11006).

Results

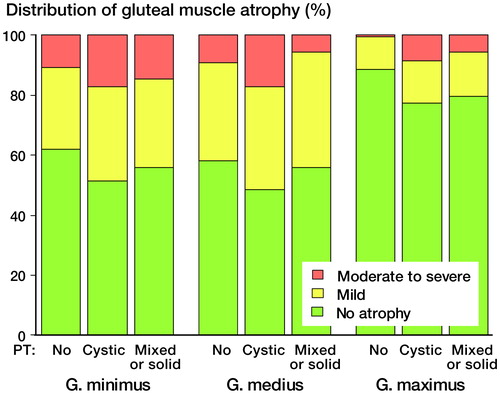

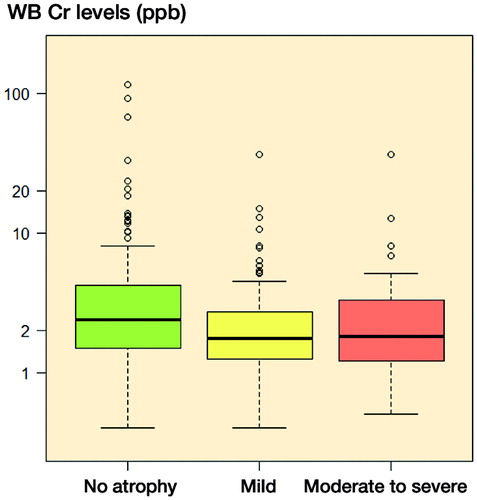

Clinical and radiological details of patients are given in . There was no statistically significant difference in prevalence of atrophy between g. minimus and g. medius muscles (p = 0.6) (). Atrophy in g. maximus was, however, less common than atrophy in g. minimus (p < 0.001) or in g. medius (p < 0.001) (). Elevated WB Cr values (> 5 ppb) were detected in 48 patients (18%) and elevated WB Co values were detected in 130 patients (49%). In general, muscle atrophy was equally common in patients with elevated WB Cr or Co values as in those patients with normal blood metal ion levels (Figure 2, see Supplementary data). Moderate-to-severe g. minimus muscle atrophy was more common in patients with WB Cr levels exceeding 5 ppb than in those with levels of less than 5 ppb (p = 0.02). No other significant differences were observed between patients with elevated and non-elevated blood metal ion levels. Interestingly, median WB Cr levels were higher in cases without g. medius atrophy than in cases with mild or moderate-to-severe atrophy (2.4 ppb as opposed to 1.75 ppb and 1.80 ppb, respectively) (p = 0.02) (). No other statistically significant differences in median WB Cr and WB Co levels were observed in relation to grade of atrophy in other muscle groups (all p > 0.05).

Figure 3. Box plot showing median WB Cr levels, interquartile range (boxes), and 95% CIs (whiskers) with outliers (circles), presented according to grade of g. medius atrophy.

Table 1. Clinical and radiological details of the patients

Table 2. Prevalence (%) of fatty atrophy in each of the gluteal muscles

There was a borderline significant (p = 0.05) but relatively small difference in the distribution of grade of atrophy in g. maximus across different PT findings (). Absence of atrophy in g. maximus was most common in patients without PT in MRI. No statistically significant differences were seen in the distribution of atrophy in g. medius (p = 0.13) or g. minimus (p = 0.4) across different PT findings.

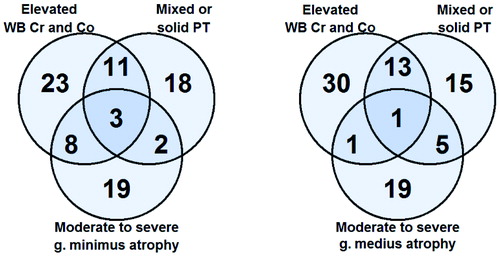

It was rare to have a combination of all 3 findings of interest (moderate-to-severe gluteal atrophy, elevated WB Cr and Co levels, and mixed-type or solid-type PT) (). The most common combination of abnormal findings was elevated blood metal ions and mixed-type or solid-type PT in MRI. In most of the patients, however, each of the abnormal findings was seen to be unrelated to other findings.

Figure 5. Venn diagrams showing the overlapping of findings of interest in patients with moderate-to-severe g. minimus atrophy (left panel) and with moderate-to-severe g. medius atrophy (right panel). Patients with moderate-to-severe g. maximus atrophy are not shown because of the very low prevalence.

There were 9 theoretical endpoints to be used in the log-binomial regression. 3 out of 9 outcome variables had missing data, i.e. there were empty cells when examining contingency tables with the outcome variable tabulated against each categorical covariate. Thus, severe g. medius atrophy and moderate-to-severe or severe g. maximus atrophy could not be used as outcome variable in logistic regression. When we examined the remaining 6 possible outcome variables in logistic regression, LR test was statistically significant in 3 models offering at least 1 significant prediction variable (Table 3, see Supplementary data). PRs from these 3 models were interpreted in Table 4 (see Supplementary data). In the regression models M1 and M4, only “preoperative diagnosis other than OA” was significantly associated with presence of mild-to-severe g. minimus atrophy and mild-to-severe g. medius atrophy in the MRI. “Preoperative diagnosis other than OA”, male sex, and cystic pseudotumor were associated with the presence of mild-to-severe g. maximus atrophy in the logistic model M6.

Discussion

Our study outlines the prevalence and factors associated with gluteal muscle atrophy in a consecutive series of patients operated on with LD MoM hip replacement. This is the largest cohort of consecutively operated patients to be reported to date to have undergone a full WB metal ion analysis combined with full-scale assessment of soft tissue changes identified in postoperative MRI. Moderate-to-severe gluteal muscle atrophy was uncommon, but low-grade atrophy was seen in up to one third of the patients. Presence of atrophy was not associated with elevated WB metal ion levels, or pseudotumors seen by MRI. These results contradict previous reports (Toms et al. Citation2008, Sabah et al. Citation2011, Berber et al. Citation2015).

Limping, abductor weakness, and Trendelenburg sign suggest the presence of severe gluteus medius muscle atrophy or avulsion of its tendon attachment to the greater trochanter. The clinical relevance or prevalence of gluteal muscle atrophy is relatively unknown both in patients suffering from hip osteoarthritis and in those scheduled for total hip arthroplasty. Comparison of patients with hip OA with healthy subjects has revealed that OA patients tend to have a higher amount of fatty atrophy and weakened muscle function in hip abductors (Rasch et al. Citation2007). Many authors have tried to state the clinical significance of muscle fatty atrophy after THA. Pfirrmann et al. (Citation2005) reported that the presence of fatty atrophy in g. medius muscle—but not g. minimus muscle—was associated with a higher incidence of symptoms in patients with non-MoM hip replacements. Müller et al. (Citation2010) did not find any association between the presence of g. minimus atrophy and functional outcome in patients with non-MoM hip replacements. The only study to assess patients with LD MoM hip replacements found that neither g. medius nor g. minimus fatty atrophy was associated with symptoms (Chang et al. Citation2012).

Several authors have stated that gluteal muscle atrophy is a common finding in patients with confirmed or suspected ARMD (Toms et al. Citation2008, Sabah et al. Citation2011, Berber et al. Citation2015). Thus, we investigated the association between gluteal muscle atrophy and ARMD-related findings, namely pseudotumors and elevated WB Cr and Co levels. A strength of our study, compared to previous studies, was our patient population. We analyzed an unselected cohort of consecutively operated patients from a single center who had a systematic follow-up; the possible overrepresentation of more complicated cases that may be seen in hospitals that act as tertial referral centers is avoided. Our results are therefore likely to reflect the true prevalence of abnormal imaging findings in patients with MoM hip replacements. MARS MRI is an expensive diagnostic modality, so it is at least equally important to investigate the prevalence and context of a certain complication as it is to examine the clinical appearance and possible associations. When examining risk factors and associations with particular pathologies, an unselected and prospective cohort of patients meets the requirements for regression analysis and reduces the selection bias.

We acknowledge that the present study had several limitations. The first was the lack of longitudal follow-up. Repeated imaging is needed to establish the natural history of muscle atrophy. Secondly, since we suggest that preoperative muscle atrophy is the major cause of the postoperative atrophy, ideally we should have included preoperative muscle status as a covariate in the regression model. Such information was not available for this study. Thirdly, several patients (n = 19) were revised before the first screening (n = 8 for ARMD). Our cohort is therefore missing the very early cases with ARMD, and thus also the complete natural variation in ARMD.

There is very little literature describing muscle abnormalities in patients with MoM hip replacements, and what exists mostly concerns ARMD (Toms et al. Citation2008, Sabah et al. Citation2011, Wynn-Jones et al. Citation2011, Chang et al. Citation2012, Hayter et al. Citation2012). A major limitation is that several studies reporting gluteal muscle atrophy in patients with MoM hip replacements have include non-consecutively operated patients, thus introducing selection bias (Toms et al. Citation2008, Sabah et al. Citation2011, Berber et al. Citation2015). We performed all the MoM hip arthroplasties through a posterior approach. Our results clearly indicate that mild muscle atrophy is common in all gluteal muscles in patients who have undergone LD MoM THR with posterior approach. However, moderate or severe muscle atrophy appears to be quite uncommon.

When considering muscle atrophy after hip arthroplasty, an important issue is the effect of the surgical approach. The posterior approach that we used detaches the external rotators, which commonly atrophy. With the posterior approach, neither g. minimus nor g. medius are detached whereas the Hardinge, i.e. lateral, approach requires splitting of g. medius and partial detachment of g. medius tendon insertion. It is therefore likely that the g. medius muscle atrophy is more prevalent when a lateral approach has been used. A recent study by Winther et al. (Citation2015) suggests that the posterior approach had the least negative effect on abduction and leg press up to 6 weeks postoperatively. In previous studies dealing with muscle atrophy after MoM hip arthroplasty, the authors have not described the surgical approach that was used—or several different approaches have been used. Thus, the prevalence of muscle atrophy in our study and in these other recent studies cannot be compared.

Apart from the surgical approach used, development of gluteal muscle atrophy is a multifactorial process. Muscle inactivation due to nerve damage, nerve root compression, neuropathy, or disuse because of pain caused by hip OA or surgery may all result in muscle atrophy. The etiology of gluteal muscle atrophy in patients with MoM hip replacement who have developed ARMD is unknown. A pseudotumor may compress the surrounding muscles or nerves, resulting in atrophy. Also, a toxic effect of wear debris may have a role. We were unable to establish a relationship between the presence of gluteal muscle atrophy and factors associated with ARMD, namely elevated blood metal ion levels and pseudotumors. The presence of a cystic pseudotumor, which is considered to be the mildest form of a pseudotumor, in MRI was associated with mild-to-severe g. maximus muscle atrophy. More severe forms of pseudotumors, i.e. mixed-type and solid-type, were not associated with muscle atrophy. If muscle atrophy was a direct consequence of adverse local tissue reaction, it would have been logical that the more severe this reaction, the more likely that muscle atrophy would occur. On the other hand, cystic pseudotumors may grow in size more easily—resulting in muscle compression and possibly atrophy. This might explain our findings. The most common mutual finding was the presence of elevated blood metal ions and mixed or solid pseudotumor in MRI. This is a usual combination of clinical findings in patients who have developed ARMD around their MoM hip replacement. In the present study, however, moderate-to-severe gluteal muscle atrophy was usually seen in MRI without these 2 other findings. Severe g. minimus muscle atrophy was associated with elevated WB Cr levels (> 5 ppb), and patients with moderate g. maximus atrophy had a higher prevalence of pseudotumors than those without atrophy. Despite being statistically significant, the differences in prevalence were rather small. Moderate-to-severe gluteal muscle atrophy in general was rare, and these differences were not observed in multivariate analysis.

2 significant findings of the current study suggest that gluteal muscle atrophy seen by MRI does not predict either the presence or the severity of ARMD in patients with MoM hip replacement. First, we found that gluteal muscle atrophy seen by MRI was neither associated with blood metal ion levels nor with pseudotumor severity. Secondly, “preoperative diagnosis other than OA” was the only significant predictor of muscle atrophy seen by postoperative MRI. These findings suggest that it is the preoperative condition of the gluteal muscles that most probably dictates the presence of atrophy after MoM hip arthroplasty. It is likely that patients with a non-OA diagnosis such as developmental dysplasia of the hip or Legg-Calve-Perthes disease will have had a longer period of symptoms, disuse of the muscle, and altered biomechanics, thus increasing the likelihood of preoperative muscle atrophy. Rasch et al. (Citation2009) stated that preoperatively identified hip muscle atrophy persists well up to 2 years postoperatively. In a recent study, Berber et al. (Citation2015) reported that progression of gluteal muscle atrophy was common in patients with MoM hip replacement. Their study involved a selected cohort of patients from a tertiary referral center and selection bias was therefore likely to be present (i.e. a higher proportion of patients with more severe forms of ARMD). Thus, the true prevalence of progressive atrophy is still largely unknown. It must be emphasized, however, that our results can only be generalized to patients who have been operated on through the posterior approach with an average follow-up of 4 years. Patients operated on through the Hardinge approach may have a completely different prevalence of gluteal muscle atrophy, and in such patients the severity of ARMD might also be associated with the presence/severity of muscle atrophy. For example, if an aggressive pseudotumor extends through an incompletely healed g. medius tendon attachment, causing tendon avulsion, this may lead to severe g. medius atrophy.

We found a very low prevalence of moderate-to-severe gluteal muscle atrophy in our patients with ASP XL MoM total hip replacements. Thus, our study may have been underpowered to find an association between moderate-to-severe atrophy and ARMD-related findings. On the other hand, this low prevalence of moderate-to-severe atrophy indicates that even if atrophy was associated with ARMD, it would be the case only in a small subgroup of patients. There has also been a lack of studies examining these same issues in patients operated on through other approaches.

In summary, our results suggest that gluteal muscle atrophy is not specifically associated with ARMD, at least not in patients who have been operated on through the posterior approach. Muscle atrophy was equally common in patients with non-elevated and elevated blood metal ion levels, and nor was there any correlation between muscle atrophy and more severe forms of pseudotumors (mixed-type or solid-type). Moderate-to-severe atrophy was rare, and it was also rarely seen in combination with mixed-type or solid-type pseudotumor, or with elevated blood metal ion levels. It remains to be seen whether gluteal muscle atrophy is associated with ARMD in patients with MoM hip replacements, who have been operated on through approaches other than the posterior one.

Supplementary data

The MR protocol, details of statistics, Figure 2, and Tables 3 and 4 are available on the Acta Orthopaedica website at www.actaorthop.org, identification number 8703.

No competing interests declared.

AR: study design, data collection and analysis, and writing of the paper. TP and JN: critical review of the paper. PE: study design and data collection. AE: study design and critical review of the paper.

- Bal B S, Lowe J A. Muscle damage in minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: MRI evidence that it is not significant. Instr Course Lect 2008; 57: 223-9.

- Berber R, Khoo M, Cook E, Guppy A, Hua J, Miles J, Carrington R, Skinner J, Hart A. Muscle atrophy and metal-on-metal hip implants. Acta Orthop 2015; Jan 14. [Epub ahead of print].

- Bisschop R, Boomsma M F, Van Raay J J, Tiebosch A T, Maas M, Gerritsma C L. High prevalence of pseudotumors in patients with a birmingham hip resurfacing prosthesis: A prospective cohort study of one hundred and twenty-nine patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95 (17): 1554-60.

- Bolland B J, Culliford D J, Langton D J, Millington J P, Arden N K, Latham J M. High failure rates with a large-diameter hybrid metal-on-metal total hip replacement: Clinical, radiological and retrieval analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93 (5): 608-15.

- Browne J A, Bechtold C D, Berry D J, Hanssen A D, Lewallen D G. Failed metal-on-metal hip arthroplasties: A spectrum of clinical presentations and operative findings. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468 (9): 2313-20.

- Carli A, Reuven A, Zukor D J, Antoniou J. Adverse soft-tissue reactions around non-metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty - a systematic review of the literature. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2011; 69Suppl1: S47-51.

- Chang E Y, McAnally J L, Van Horne J R, Statum S, Wolfson T, Gamst A, Chung C B. Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: Do symptoms correlate with MR imaging findings? Radiology 2012; 265 (3): 848-57.

- Hart A J, Sabah S A, Bandi A S, Maggiore P, Tarassoli P, Sampson B, A Skinner J. Sensitivity and specificity of blood cobalt and chromium metal ions for predicting failure of metal-on-metal hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93 (10): 1308-13.

- Hart A J, Satchithananda K, Liddle A D, Sabah S A, McRobbie D, Henckel J, Cobb J P, Skinner J A, Mitchell A W. Pseudotumors in association with well-functioning metal-on-metal hip prostheses: A case-control study using three-dimensional computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94 (4): 317-25.

- Hayter C L, Gold S L, Koff M F, Perino G, Nawabi D H, Miller T T, Potter H G. MRI findings in painful metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199 (4): 884-93.

- Lainiala O, Elo P, Reito A, Pajamaki J, Puolakka T, Eskelinen A. Comparison of extracapsular pseudotumors seen in magnetic resonance imaging and in revision surgery of 167 failed metal-on-metal hip replacements. Acta Orthop 2014a; 85 (5): 474-9.

- Lainiala O, Eskelinen A, Elo P, Puolakka T, Korhonen J, Moilanen T. Adverse reaction to metal debris is more common in patients following MoM total hip replacement with a 36 mm femoral head than previously thought: results from a modern MoM follow-up programme. Bone Joint J 2014b; 96(12): 1610-7

- Liddle A D, Satchithananda K, Henckel J, Sabah S A, Vipulendran K V, Lewis A, Skinner J A, Mitchell A W, Hart A J. Revision of metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty in a tertiary center: a prospective study of 39 hips with between 1 and 4 years of follow-up. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(3): 237-45.

- Mistry A, Cahir J, Donell ST, Nolan J, Toms AP. MRI of asymptomatic patients with metal-on-metal and polyethylene-on-metal total hip arthroplasties. Clin Radiol 2011; 66(6): 540-5.

- Müller M, Tohtz S, Winkler T, Dewey M, Springer I, Perka C. MRI findings of gluteus minimus muscle damage in primary total hip arthroplasty and the influence on clinical outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010; 130 (7): 927-35.

- Nawabi D H, Gold S, Lyman S, Fields K, Padgett D E, Potter H G. MRI predicts ALVAL and tissue damage in metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014; 472 (2): 471-81.

- Nishii T, Sakai T, Takao M, Yoshikawa H, Sugano N. Ultrasound screening of periarticular soft tissue abnormality around metal-on-metal bearings. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27 (6): 895-900.

- Pfirrmann C W, Notzli H P, Dora C, Hodler J, Zanetti M. Abductor tendons and muscles assessed at MR imaging after total hip arthroplasty in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients. Radiology 2005; 235 (3): 969-76.

- Rasch A, Bystrom A H, Dalen N, Berg H E. Reduced muscle radiological density, cross-sectional area, and strength of major hip and knee muscles in 22 patients with hip osteoarthritis. Acta Orthop 2007; 78 (4): 505-10.

- Rasch A, Bystrom A H, Dalen N, Martinez-Carranza N, Berg H E. Persisting muscle atrophy two years after replacement of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91 (5): 583-8.

- Reito A, Puolakka T, Elo P, Pajamaki J, Eskelinen A. High prevalence of adverse reactions to metal debris in small-headed ASR hips. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471 (9): 2954-61.

- Sabah S A, Mitchell A W, Henckel J, Sandison A, Skinner J A, Hart A J. Magnetic resonance imaging findings in painful metal-on-metal hips: A prospective study. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26 (1): 71-6.

- Shrier I, Platt R W. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol 2008; 8: 70.

- Toms A P, Marshall T J, Cahir J, Darrah C, Nolan J, Donell S T, Barker T, Tucker J K. MRI of early symptomatic metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: A retrospective review of radiological findings in 20 hips. Clin Radiol 2008; 63 (1): 49-58.

- Winther S B, Husby V S, Foss O A, Wik T S, Svenningsen S, Engdal M, Haugan K, Husby O S. Muscular strength after total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2015 Jul 3:1-7. [Epub ahead of print].

- Wynn-Jones H, Macnair R, Wimhurst J, Chirodian N, Derbyshire B, Toms A, Cahir J. Silent soft tissue pathology is common with a modern metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2011; 82 (3): 301-7.