Abstract

Background and purpose — Aseptic revisions comprise 80% of revision total knee arthroplasties (TKAs). We determined the incidence of re-revision TKA, the reasons for re-revision, and risk factors associated with these procedures.

Patients and methods — We conducted a retrospective cohort study of 1,154 patients who underwent aseptic revision TKA between 2002 and 2013 and were followed prospectively by a total joint replacement registry in the USA. Revision was defined as any operation in which an implanted component was replaced. Patient-, surgeon-, and procedure-related risk factors were evaluated. Survival analyses were conducted.

Results — There were 114 re-revisions (10%) with a median time to reoperation of 3.6 years (interquartile range (IQR): 2.6–5.2). The infection rate was 2.9% (34/1,154) and accounted for 30% of re-revisions (34 of 114). In adjusted models, use of antibiotic-loaded cement was associated with a 50% lower risk of all-cause re-revision surgery (hazard ratio (HR) = 0.5, 95% CI: 0.3–0.9), age with a 20% lower risk for every 10-year increase (HR = 0.8, CI: 0.7–1.0), body mass index (BMI) with a 20% lower risk for every 5-unit increase (HR = 0.8, CI: 0.7–1.0), and a surgeon’s greater cumulative experience (≥ 20 cases vs. < 20 cases) with a 3 times higher risk of re-revision (HR = 2.8, CI: 1.5–5).

Interpretation — Revised TKAs were at high risk of subsequent failure. The use of antibiotic-loaded cement, higher age, and higher BMI were associated with lower risk of further revision whereas a higher degree of surgeon experience was associated with higher risk.

The revision burden for total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in the USA has been approximately 10% for the past decade, and the total number of revisions per year has been predicted to increase to approximately 250,000 by 2030 (Kurtz et al. Citation2007).

Few studies have specifically examined the re-revision rate of revision TKA performed for aseptic causes (Sheng et al. Citation2004, Bae et al. Citation2013, Luque et al. Citation2014). The majority of these studies have included revisions performed for septic primary TKA in their index cohort. However, revision for infection is a different procedure from revision for aseptic causes. The different considerations include bone and soft-tissue quality following infection and initial debridement, the need in some cases for staged revision, and the impact of non-modifiable variables such as the virulence of the infecting organism.

As aseptic revisions make up approximately 80% of all revision TKAs, it is important to understand the overall outcomes of these procedures using current surgical techniques and protocols and also the risk factors that can affect the results. Due to the overall success of primary TKA and therefore the relative rarity of revision arthroplasty, large cohorts are needed to conduct rigorous analyses and identify modifiable risk factors from which to derive best practices. Total joint replacement registries (TJRRs) are ideally suited to this task.

This study evaluated patients who were prospectively entered into a large US-based community TJRR and who underwent a primary TKA that was subsequently revised for aseptic reasons. The aim of this investigation was to determine the incidence of re-revision following aseptic revision TKA, the causes of failure, and any patient-, surgeon-, hospital-, or procedure-related risk factors that affected the outcome of the index revision surgery.

Methods

Study design, data collection, and inclusion criteria

We conducted a retrospective cohort study. A TJRR was used to identify individuals who underwent aseptic revision following a primary TKA in a large integrated US healthcare system between April 2001 and December 2012, and their outcomes. Data collection, participation, and information on the TJRR has been published elsewhere (Paxton et al. Citation2010,Citation2013). In brief, the TJRR uses both paper-based and electronic collection to identify patient characteristics, implant and surgical information, and electronic algorithms followed by chart review to capture the outcomes of interest. This information is supplemented with data from several other sources, including the institution’s electronic medical record (EMR), administrative claims data, membership information (e.g. membership attrition due to healthcare coverage loss or death), a diabetes registry, and other institutional databases. Intraoperative information is collected by the surgeon at the point of care. International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9 CM) algorithms are used to search the EMR and administrative data for reoperations and complications, and these events are confirmed through chart review. The voluntary participation in the registry is 95% (Paxton et al. Citation2013).

All aseptic revisions after a primary TKA during the period of interest were included in the study. Individuals whose primary TKA had been performed outside of this integrated healthcare system or before the start of the registry (April 2001) were not included. Only patients with primary TKAs in the system were included, so that the index revision procedure included in the study could be confirmed to be the first revision after the primary TKA. The study sample included cases from 44 medical facilities and 177 surgeons in 6 regions of the USA (Southern California, Northern California, Colorado, Hawaii, Northwest, and Mid-Atlantic).

Outcome of interest

The endpoint of this study was the first re-revision TKA (aseptic or septic). Re-revision was defined as any operation in which a previously implanted component of a revision TKA was replaced. Reasons for the index revision procedure and re-revision procedure were recorded by the surgeons in the operative forms of the TJRR and confirmed through chart review by a trained clinical research associate. For any one procedure, more than 1 reason for revision can be listed by the operating surgeon.

Exposures of interest

The re-revision risk factors evaluated were grouped into patient-, surgeon-, hospital-, and procedure-related variables. The patient risk factors evaluated at the time of initial revision were: age (continuous per 10-year increment), sex, race (white vs. other), body mass index (BMI, continuous per 5-unit increment), diabetes (yes vs. no), and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score (< 3 vs. ≥ 3). Surgeon-related variables included the average number of revisions performed by a surgeon annually (continuous), whether or not he or she had received total joint arthroplasty fellowship training (yes vs. no), and the running total of revision surgeries performed at the time of the index revision procedure (≥ 20 cases vs. < 20 cases). Procedure variables included the use of antibiotic-loaded bone cement (ALC; yes vs. no) and the selection of a hinged prosthesis at the time of index revision (yes vs. no). Cementless revisions and partial revisions in which ALC was not used were grouped under the “no ALC” category.

Statistics

Survival analyses were performed with cumulative failure probability plots and mixed-effects Cox regression models with surgeon and facility intercept as (normal) random effects, together with surgeon- and facility-specific means corresponding to patient effects in order to control for stable surgeon and facility characteristics (Sjolander et al. Citation2013). A between-within mixed-effects model was used to make random-effects inferences and to more accurately partition between- and within-cluster effects, leading to within-cluster effects that are not confounded by surgeon and facility factors. The dependent variable (outcome) was time to re-revision surgery in years (i.e. survival time), with loss to follow-up (either date of membership termination or death) treated as censored cases with survival time calculated based on the time these events occurred. Despite the fact that death is an informative censoring event, we modeled the re-revision event as the cause-specific hazard in this study because it would be a more direct estimate of treatment effectiveness to have the treatment effect conflate with the probability of death.

To account for missing values in some of the variables, multiple imputations were performed to create 50 versions of the analytic dataset. Multiple imputations were used to increase precision, and to possibly reduce bias in the estimates. Each dataset was analyzed separately using the same model and the results were combined using Rubin’s rules (Rubin Citation1987). The imputation model included all covariates as well as the event indicator and the Nelson-Aalen estimator of the cumulative baseline hazard at the time of event or censoring for each case. Proportional hazard assumptions were tested using a Kolmogorov-type supremum test (Lin et al. Citation1993) in one of the imputed datasets, where the p-values are based on the number of simulated curves that have values more extreme than the most extreme point of the observed curve. Results showed that surgeon fellowship training violated the proportional hazards assumption with an effect of estimated coefficient equivalent to a hazard ratio of 0.01 at its most extreme; yet, by 365 days this waned to a hazard ratio of 1 and remained constant thereafter. However, since the overall time average effect is of more clinical interest, we report it without using a time-dependent variable. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the risk of re-revision are reported.

Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 using the MI procedure for multiple imputation models, and with R software version 3.1.2 using the coxme() function of the COXME package for mixed-effects Cox models. Type-I error bounded at 0.05 was used as the threshold for statistical significance for exposure variables.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board before it started (no. 5488, last approval 3/18/2015). No outside funding was obtained for this study.

Results

The study cohort consisted of 1,154 aseptic revision TKAs. The mean age of the cohort was 65 (SD 10) years old, 61% were female, 32% were diabetic, 64% were white, 28% had a BMI greater than 35, and 52% had an ASA score of < 3. ()

Table 1. Patient demographics and characteristics of revised patients, overall and according to re-revision status

During the study period, 8.9% of patients were lost to follow-up and 4.5% of patients died prior to re-revision. The most commonly reported index revision diagnoses were instability (31%), followed by pain (30%) and aseptic loosening (26%). There were 25 revisions (2.2%) where “pain” was the only diagnosis reported (). Antibiotic-loaded cement was used in 27% of the index revision TKAs. Surgeons who did less than 10 revisions on average per year performed 75% of the revision TKAs ().

Table 2. Reasons for index revision procedures and re-revision proceduresTable Footnotea. Values are number (percentage)

Table 3. Surgeon, hospital, and implant characteristics for index revision procedure (total cohort and according to re-revision status)

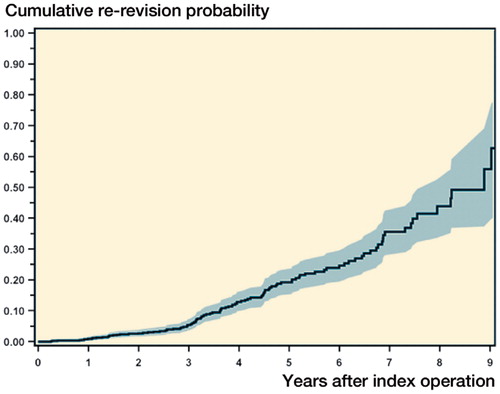

The crude incidence of re-revision surgeries was 9.9% and the median time to revision was 3.6 years (IQR: 2.6–5.2). At 2 years, the cumulative probability of re-revision was 2.9% (CI: 1.9–4.3) and at 5 years it was 20% (CI: 16–24) (). The most common reasons for re-revision surgery were infection, instability, pain, and aseptic loosening ().

Figure 1. Cumulative probability of re-revision (with 95% CI) after index revision total knee arthroplasty.

After adjusting for all other risk factors (), for every 5-unit increase in BMI the risk of re-revision surgery decreased (HR = 0.8, 95% CI: 0.7–1.0), antibiotic-loaded cement was independently associated with a lower risk of re-revision surgery (HR = 0.5, CI: 0.3–0.9), and a surgeon’s greater cumulative experience (≥ 20 vs. < 20 cases) was associated with a higher risk of re-revision surgery (HR = 2.8, CI: 1.5–5). Every 10-year increase in age was associated with a 20% lower risk of revision (HR = 0.8, CI: 0.7–1.0). No other factors evaluated were found to be associated with risk of re-revision surgery.

Table 4. Risk factors for re-revision TKA

Discussion

In our large, community-based cohort of TKA patients who were initially revised for aseptic causes between 2001 and 2012, we found that revised TKAs were at a high risk of failure. In addition, of all the risk factors evaluated, we found that the use of antibiotic-loaded cement, higher age, and higher BMI were associated with less risk of further revision whereas—surprisingly—greater surgeon experience was associated with an increased risk of subsequent reoperation.

We found an overall crude incidence of revision of 10% with a median follow-up time of 3.6 years. The cumulative probability of re-revision at 2 years was 2.9% and at 5 years it was 20%. Similarly high failure rates of revision TKA procedures have been reported by other authors (Sheng et al. Citation2006a, Mortazavi et al. Citation2011, Bae et al. Citation2013, Luque et al. Citation2014). Sierra et al. (Citation2004) reported a 40% cumulative revision risk at 20 years in 1,814 cases operated over a 30-year period. The Finnish Arthroplasty Register reported 79% survivorship of revision TKA at 10 years in 2,637 revision TKAs (Sheng et al. Citation2006b). In a smaller and more recent study by Luque et al. (Citation2014), 125 aseptic revisions were reported with a minimum follow-up of 7 years and an 8-year survival of 88%. The causes of revision in our cohort parallel those presented in other studies where infection, aseptic loosening, and pain due to instability or stiffness consistently remain the leading causes of revision (Sheng et al. Citation2006a, Mortazavi et al. Citation2011, Bae et al. Citation2013, Luque et al. Citation2014).

We found that the use of antibiotic cement at the time of the index revision was associated with half the risk of future all-cause revision. In a recent randomized controlled trial, the effect of vancomycin-loaded cement use in the context of 183 low-risk, aseptic revision TKAs was evaluated and a statistically significant reduction in postoperative deep infections at a minimum follow-up of 36 months was reported (none in the intervention group became infected, as compared to 7% in the control group) (Chiu and Lin Citation2009). However, several studies that have evaluated the association between antibiotic-loaded cement and infection after primary TKA surgery have arrived at inconsistent results. A review did not find antibiotic-loaded cement to be consistently associated with a lower risk of infection in modern, primary TKA (Jiranek et al. Citation2006). Also, a study by Namba et al. (Citation2013), using the same data source as in our study, found that—paradoxically—antibiotic-loaded cement was associated with a slightly higher risk of surgical site infection after TKA. The higher risk of infection in revision TKA than in primary TKA procedures is probably the reason why we identified such a substantially lower risk of re-revision surgery in cases where antibiotic-loaded cement was used. Furthermore, the use of antibiotic bone cement in cases of subclinical or undiagnosed infections might favorably affect the results of the procedure.

A second factor, the surgeon’s cumulative experience at the time of the index revision, was associated with a higher risk of re-revision surgery. As the most complex and high-risk cases are referred to more experienced surgeons, we believe that this finding is probably a proxy for case complexity, which is something we could not adjust for in our analysis. To our knowledge, the finding that higher BMI was associated with a small but statistically significantly lower risk of revision has not been reported elsewhere with respect to outcomes of revision TKA surgery, while the decrease in risk with older age has (Sheng et al. Citation2006b). We can only infer that activity levels may be lower in older patients or in those with a higher BMI, and that a combination of higher morbidity, higher perceived risk, and lower demand may lead to a lower revision risk associated with increasing age (Sheng et al. Citation2006b).

After adjusting for all other risk factors, we did not find sex, race, ASA score, diabetic status, surgeon volume, hospital volume, surgeon’s TJA fellowship training, or use of hinged prosthesis at index revision to be associated with the risk of re-revision surgery.

Our study had several limitations and strengths. Among the limitations, some of the data sourced for this study required voluntary surgeon participation (currently at 95%) with non-differential rates of participation across sites. There were missing data, but they were handled in the statistical analysis using multiple imputations. We do not feel that either of these limitations would affect outcomes. In addition, due to our sample size, which limited by the number of factors that could be evaluated at this time, in our analysis we were not able to evaluate the influence of surgical factors such as fixation method (i.e. cemented, uncemented, or hybrid), the extent of the index revision (i.e. 1, 2, or more components revised) and structural issues such as bone quality. Doing this might identify other risk factors for early revision. Furthermore, our decision to limit the cohort to those patients for whom the primary procedure had been captured in the registry limited us to a short follow-up period. Longer follow-up might have shown a higher percentage of patients revised for component wear or loosening. It is also likely that, as with any study of revision TKA, some patients in the cohort may have had an undiagnosed low-grade infection and that this might have skewed the overall risk of infection. Regarding surgeon experience, we note that the results can only reflect the period of data collection for the study and not lifetime experience.

Among the strengths of the present study, we can include the large number of cases treated across multiple medical centers in a community-based setting, which should have provided data comparable to the experience of the majority of community surgeons. Furthermore, there was only a small possibility of data-handling bias due to the use of our integrated electronic medical record. Additionally, all of the outcomes evaluated in this study were manually adjudicated by a trained research assistant to guarantee the accuracy and integrity of the information reported, thus ensuring the high internal validity of the information reported.

In summary, the most striking finding from our study of 1,154 aseptic TKA revisions is that the use of antibiotic-loaded cement was associated with half the risk of subsequent revision surgery. Infection, instability, pain, and aseptic loosening remain ongoing challenges associated with a 20% cumulative probability of failure at 5 years. Surgeons and patients alike must be cognizant of the potential for poor long-term outcomes following revision TKA.

All the authors contributed to the study design and contributed substantially to collecting the data, interpreting the results, drafting the article, and to revision. PHC and MCSI conducted the statistical analysis.

No competing interests declared.

- Bae D K, Song S J, Heo D B, Lee S H, Song W J. Long-term survival rate of implants and modes of failure after revision total knee arthroplasty by a single surgeon. J Arthroplasty 2013; 28(7): 1130-4.

- Chiu F Y, Lin C F. Antibiotic-impregnated cement in revision total knee arthroplasty. A prospective cohort study of one hundred and eighty-three knees. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009; 91(3): 628-33.

- Jiranek W A, Hanssen A D, Greenwald A S. Antibiotic-loaded bone cement for infection prophylaxis in total joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88(11): 2487-500.

- Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89(4): 780-5.

- Lin D Y, Wei L J, Ying Z. Checking the Cox model with cumulative sums of martingale-based residuals. Biometrika 1993; 80(3): 557-72.

- Luque R, Rizo B, Urda A, Garcia-Crespo R, Moro E, Marco F, Lopez-Duran L. Predictive factors for failure after total knee replacement revision. Int Orthop 2014; 38(2): 429-35.

- Mortazavi S M, Molligan J, Austin M S, Purtill J J, Hozack W J, Parvizi J. Failure following revision total knee arthroplasty: infection is the major cause. Int Orthop 2011; 35(8): 1157-64.

- Namba R S, Inacio M C, Paxton E W. Risk factors associated with deep surgical site infections after primary total knee arthroplasty: an analysis of 56,216 knees. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013; 95(9): 775-82.

- Paxton E W, Inacio M C, Khatod M, Yue E J, Namba R S. Kaiser Permanente National Total Joint Replacement Registry: aligning operations with information technology. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468(10): 2646-63.

- Paxton E W, Kiley M L, Love R, Barber T C, Funahashi T T, Inacio M C. Kaiser Permanente implant registries benefit patient safety, quality improvement, cost-effectiveness. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2013; 39(6): 246-52.

- Rubin D B. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1987.

- Sheng P, Lehto M, Kataja M, Halonen P, Moilanen T, Pajamaki J. Patient outcome following revision total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Int Orthop 2004; 28(2): 78-81.

- Sheng P Y, Jamsen E, Lehto M, Pajamaki J, Halonen P, Konttinen Y T. Revision total knee arthroplasty with the total condylar III system: a comparative analysis of 71 consecutive cases of osteoarthritis or inflammatory arthritis. Acta Orthop 2006a; 77(3): 512-8.

- Sheng P Y, Konttinen L, Lehto M, Ogino D, Jamsen E, Nevalainen J, Pajamaki J, Halonen P, Konttinen YT. Revision total knee arthroplasty: 1990 through 2002. A review of the Finnish arthroplasty registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006b; 88(7): 1425-30.

- Sierra R J, Cooney W P, Pagnano M W, Trousdale R T, Rand J A. Reoperations after 3200 revision TKAs: rates, etiology, and lessons learned. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; (425): 200-6.

- Sjolander A, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H, Pawitan Y. Between-within models for survival analysis. Stat Med 2013; 32(18): 3067-76.