Abstract

Background and purpose — Very little has been published on the outcome of femoral cemented revisions using a third-generation cementing technique. We report the medium-term outcome of a consecutive series of patients treated in this way.

Patients and methods — This study included 92 consecutive cemented femoral revisions performed in our department with a third-generation cementing technique and without instrumented bone impaction grafting between 1996 and 2007. The average age of the patients at revision was 66 (25–92) years. None of the patients were lost to follow-up. At review in December 2013, 55 patients were still alive and had a non-re-revised femoral revision component in situ after a mean follow-up of 11 (5–17) years.

Results — The mean preoperative Harris hip score was 50, and improved to 73 at final follow-up. 2 patients died shortly after the revision surgery. 1 stem was re-revised for aseptic loosening; this was also the only case with radiolucent lines in all 7 Gruen zones. A femoral reoperation was performed in 19 hips during follow-up, and in 14 of these 19 reoperations the femoral component was re-revised. Survivorship at 10 years, with femoral re-revision for any reason as the endpoint, was 86% (95% CI: 77–92). However, excluding 8 patients with reinfections after septic index revisions and 1 with hematogenous spread of infection from the survival analysis, the adjusted survival for re-revision for any reason at 10 years was 92% (95% CI: 83–96). With re-revision for aseptic loosening as endpoint, the survival at 10 years was 99% (CI: 90–100).

Interpretation — Femoral component revision with a third-generation cemented stem results in acceptable survival after medium-term follow-up. We recommend the use of this technique in femoral revisions with limited loss of bone stock.

Outcome reports of cemented revisions of failed total hip arthroplasties (THAs) published before 1985 were not encouraging (Amstutz et al. Citation1982, Kavanagh et al. Citation1985, Pellicci et al. Citation1985). However, once better cementing techniques became available, the results of revisions on the femoral side remarkably improved. Proper preparation of the femoral canal with complete cement removal, placement of a distal cement plug, and optimal pressurization of an adequate amount of cement are essential steps for improvement of the outcome of femoral cemented revision.

As a result of these improvements in cementing technique, studies investigating the use of these modern cementing methods in patient cohorts ranging in size from 34 to 399 hips have shown encouraging medium- to long-term results (Raut et al. Citation1996, Gramkow et al. Citation2001, Haydon et al. Citation2004, Howie et al. Citation2007, So et al. Citation2013) However, the outcome of femoral revisions using a third-generation cementing technique (which comprises pulsatile bone lavage, the use of a distal intramedullary plug, retrograde injection of vacuum-mixed low-viscosity cement with a cement gun, and solid pressurization) is still poorly documented. Only 2 groups have reported their results: 1 study was based on 34 hips after a mean follow-up of 11.3 years and all the stems used were long (So et al. Citation2013), and the other group reported the results of 83 hips after a mean of 3.6 years (Eisler et al. Citation2000).

We analyzed the clinical and radiographic outcome, survivorship, and complication rate of all 92 consecutive cemented femoral revisions performed with a third-generation cementing technique in our department between January 1996 and December 2007.

Patients and methods

Study population

All surgeries were performed between January 1996 and December 2007. All data were collected prospectively.

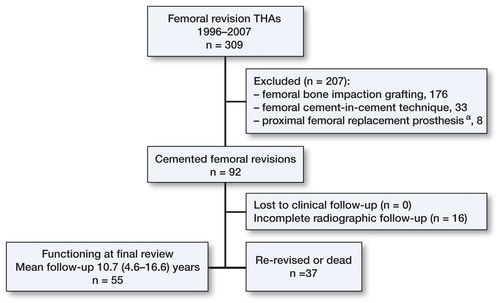

The inclusion process for this study is shown in . At our institution, we use cemented femoral components in all revision cases. However, when there is femoral bone stock loss preoperatively or intraoperatively, we generally use the femoral bone impaction grafting technique to reconstruct these defects (Schreurs et al. Citation2006). All these femoral revisions, combining cement and bone impaction grafting, were excluded from the current study. We also excluded cement-in-cement femoral revisions. All 92 “cement-only” femoral reconstructions were included in this study. Osteoarthritis was the most common reason for the primary arthroplasty and aseptic loosening was the most common reason for the revision (). These 92 femoral revisions were performed in 90 patients (58 of them women) with a mean age of 66 (25–92) years. The average weight of the patients was 73 (40–116) kg, their average height was 168 (147–198) cm, and their average body mass index (BMI) was 26 (15–44).

Figure 1. The flow chart showing the identification of eligible patients for the study. aProximal femoral replacement prosthesis placed for oncologic reasons or because the bone stock loss was too extensive to perform a conventional revision.

Table 1. Original indications for the 92 primary THAs/hemiarthroplasties and revisions

The index femoral revision was the first in 79 of the cases, the second in 11, and the third in 2. In 69 hips, the surgery performed was a revision of both components of the THA, in 10 hips only the stem of the THA was revised, and in the remaining 13 hips a conversion of a hemiarthroplasty to THA with exchange of the femoral component was performed. 87 of the 92 revision operations were performed by 1 of the 2 senior faculty surgeons (JWMG and BWS). 25 of the 29 hips with septic loosening were treated with a 2-stage procedure, using systemic antibiotics to eradicate the infecting organism for at least 6 weeks before reimplantation. The diagnosis septic loosening in the remaining 4 hips was based postoperatively on bacterial cultures taken during a 1-stage revision for presumed aseptic loosening.

Because many infections that occurred during follow-up after a septic index revision were multi-microbial, in most cases it was impossible to state whether this was a new infection with a different organism or a persistent infection with the same organism. We therefore used the following definition of reinfection in this study: all infections (persistent infection with the same organism, infection with a new organism, or multi-microbial infection) in a patient who was included in the study with a septic index revision.

Surgical technique

The posterolateral approach was used in all patients. All revision femoral components were inserted using a third-generation cementing technique with pulsatile lavage, a distal intramedullary plug, retrograde injection of vacuum-mixed low-viscosity cement with a cement gun, and solid pressurization. The components used were 78 normal-length femoral components: 76 Exeter stems (Stryker-Howmedica, Newbury, UK), 1 Muller straight stem (Sulzer, Wintherthur, Switzerland), and 1 Charnley Elite femoral component (DePuy, Leeds, UK). In addition, 13 long Exeter femoral components with a length of 205 mm or more and 1 Exeter short revision stem were used. The metal femoral heads had a diameter of 22.2 mm in 1 patient, 28 mm in 65 patients, and 32 mm in 26 patients. Simplex bone low-viscosity cement (Stryker-Howmedica, Newbury, UK) loaded with erythromycin and colistin was used in all cases.

Aftercare

Patients were mobilized under the supervision of a physiotherapist 1 or 2 days after surgery using 2 crutches, and full weight bearing immediately allowed. This protocol was modified for some patients who also had an acetabular reconstruction, depending on the type and extent of the defect and reconstruction.

The postoperative regimen included systemic antibiotics (3 intravenous doses of 1g cefazolin) for 1 day and indomethacin for 7 days to prevent heterotopic ossification. All patients received anticoagulation with Coumadin (warfarin) or low-molecular-weight heparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis for a minimum of 6 weeks.

Clinical evaluation

A standard postoperative follow-up protocol was used, with physical and radiographic examination at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year, and then on an annual or biannual basis.

Clinical evaluation was performed using the Harris hip score (HHS: worst score 0; best score 100), the Oxford hip scores (OHS: worst score 60; best score 12) (Dawson et al. Citation1996), visual analog scales (VAS) (Brokelman et al. Citation2012) for pain at rest and during physical activity on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 100 (unbearable pain), and a VAS for satisfaction on a scale from 0 (not satisfied at all) to 100 (complete satisfaction).

Radiographic evaluation

Anteroposterior radiographs taken during the last follow-up were evaluated and compared with earlier postoperative and preoperative radiographs. The radiographs were scored by 2 of the authors (MTS and BWS) by consensus. Bone stock loss was determined on preoperative radiographs and on the basis of the intraoperative findings, and was classified according to the system of the Endoklinik (Engelbrecht and Heinert Citation1987) as grade 1 in 70 hips, grade 2 in 9, grade 3 in 12, and grade 4 in 1. To determine the stem migration, we used a method as described by Fowler et al. (Citation1988); radiolucencies (complete radiolucent lines ≥ 2 mm in width) were scored with use of the classification system of Gruen. Radiographic failure was defined as a circumferential radiolucent line in all 7 Gruen zones on an anteroposterior view.

Statistics

We performed a Kaplan-Meier survivorship analysis, including determination of 95% confidence intervals (CIs), using femoral re-revision for any reason and re-revision for aseptic loosening, femoral reoperation for any reason, and subsidence of ≥ 5 mm as the endpoints. Comparisons of the survival of the different Endoklinik groups, and of the standard stems and the long stems, were performed with the log-rank test. We used the Wilcoxon signed rank test to compare the preoperative and postoperative HHS and OHS.

Analysis of the data was carried out using Graphpad Prism software version 5.03 (Graphpad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Ethics

This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Results

Clinical results

The mean preoperative HHS was 50 (29–90), and it improved to 73 (14–100) at final follow-up (p = 0.01). The mean preoperative OHS was 37 (25–53), and it improved to 25 (12–48) (p = 0.007). At last follow-up, the mean VAS score for satisfaction was 77 (15–100), the mean VAS score for pain at rest was 15 (0–80), and the mean VAS score for pain during exercise was 21 (0–90).

Intraoperative complications

1 intraoperative femoral fracture occurred during a full-length transfemoral Wagner osteotomy to remove an uncemented stem. This fracture was treated with plate fixation and cables.

Early postoperative deaths

2 patients died within 2 weeks after revision surgery. Both were octogenerians and had an ASA classification of grade 3. The first patient was admitted to our hospital after a fall, which caused a Vancouver type-B2 fracture. The patient developed lung edema during surgery and died on the first postoperative day. The second patient was admitted for unbearable pain due to protrusion of a hemiarthroplasty. The patient had congestive heart failure before surgery and died 13 days after surgery, due to cardiac failure.

Femoral reoperations and re-revisions

In 19 hips, a femoral reoperation was performed during follow-up, and in 14 of these 19 reoperations the femoral component was re-revised. The main reasons for these femoral reoperations were infection (n = 13) and periprosthetic fracture (n = 3) ().

Table 2. 19 hips with 1 or more femoral reoperations. In 14 of these cases, a re-revision of the femoral component was performed

Survivorship

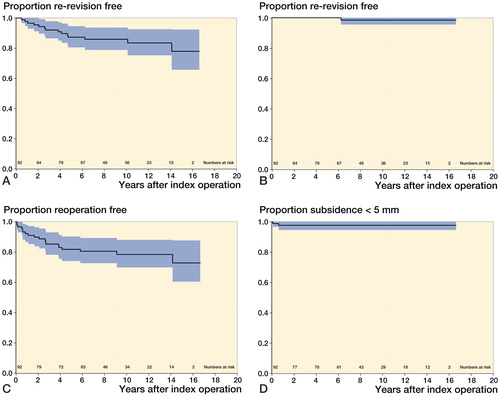

The survival of the femoral component with re-revision for any reason as the endpoint was 86% (95% CI: 77–92) at 10 years. With femoral re-revision for aseptic loosening as the endpoint, the survival at 10 years was 99% (CI: 9–100), and with femoral reoperation for any reason as the endpoint it was 79% (CI: 68–86). With a subsidence of the femoral component of ≥ 5 mm as the endpoint, the survival was 98% (CI: 91–99) ().

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curves with re-revision of the femoral component for any reason (A), aseptic loosening (B), femoral reoperation for any reason (C), or subsidence of ≥ 5 mm (D) as the endpoint.

No statistically significant differences in outcomes could be detected between the various Endoklinik categories of bone stock loss and between stem lengths.

Finally, we performed a sensitivity analysis to assess the effect of the bilateral hips in 2 patients. When we excluded these 4 hips from our survivorship analysis, the survival of the femoral component at 10 years with re-revision for any reason as the endpoint was similar to the survival outcome in the complete patient group.

Postoperative periprosthetic fractures

A reoperation for plate fixation of a postoperative periprosthetic femoral fracture was performed in 3 patients (nos. 12, 17, and 18 in ).

Postoperative infections

A femoral reoperation and/or re-revision was performed in 13 patients for septic reasons (patients 2–10 and 13–16 in ). However, 8 of these 13 patients had reinfections after septic index revisions and 1 had a hematogenous spread of infection (originating from an infected open ankle fracture; patient 3 in ). When we excluded these 9 patients from the survival analysis, the adjusted survival for re-revision for any reason at 10 years was 92% (CI: 83–96), while the survival for reoperation for any reason was 89% (CI: 79–94).

Dislocations

Dislocations occurred in 12 patients. 9 of these were treated nonoperatively and a reoperation was performed in 3 patients: in 1 patient a re-revision of only the acetabular component was performed, in 1 a Trident constrained liner (Stryker-Howmedica, Newbury, UK) was implanted, and in the last patient (no. 11 in ) the femoral component was reimplanted 1.5 cm higher using a cement-in-cement technique. 1 patient had the femoral head exchanged for one with a larger offset.

Radiographic results

Radiographic follow-up was complete in 76 revisions (), and in 16 revisions some radiographs during follow-up were missing. Even so, we could include these patients in the analysis. Radiolucent lines were observed in 24 hips. 11 patients had radiolucent lines in 1 Gruen zone, 8 patients in 2 zones, and 5 patients in 3 or more zones. In 18 of the 24 hips, these radiolucent lines were progressive. The femoral component which was re-revised for aseptic loosening was the only one with radiolucent lines in all 7 zones. The mean amount of subsidence of all femoral components was 1.5 (range 0–23) mm. 2 femoral components had subsided by ≥ 5 mm (13 and 23 mm).

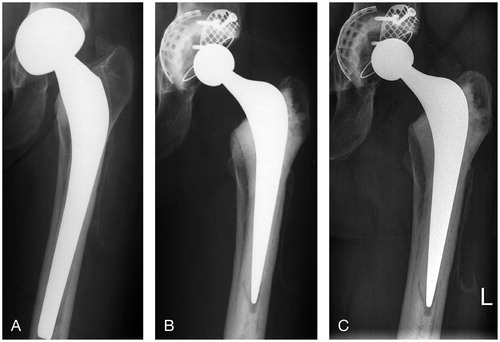

Figure 3. A. A 43-year-old woman at presentation with a loose cemented hemiarthroplasty with protrusion of the head. B. Directly after the conversion to a total hip arthroplasty (the acetabulum was reconstructed with metal meshes and bone impaction bone). C. 11 years postoperatively, showing a stable femoral and acetabular component without any signs of loosening.

Discussion

With a 10-year survivorship of 99% for the endpoint re-revision for aseptic loosening, our study shows that satisfying results can be obtained in femoral revisions using a third-generation cementing technique.

The 10-year survivorship of 86% for the endpoint re-revision for any reason, and 79% for the endpoint reoperation for any reason, are considerably less favorable than the survival for aseptic loosening. The reason for this could be that we are a tertiary referral center for the treatment of periprosthetic joint infections, and a considerable proportion of the index femoral revisions performed were septic revisions (29 of 92 cases). When we excluded the 8 patients with reinfections after septic index revisions and the 1 patient with hematogeneous spread of infection from the survival analysis, the adjusted survival for re-revision for any reason at 10 years was 92%, while the survival for reoperation for any reason was 89%. Our survival rates are comparable to those reported in other series (Raut et al. Citation1996, Gramkow et al. Citation2001, Haydon et al. Citation2004, Howie et al. Citation2007, So et al. Citation2013) (Table 3, see Supplementary data).

Our dislocation rate of 13% is high, but is similar to the 11% found by Alberton et al. (Citation2002) in a review of the literature that covered 26 reports describing 211 dislocations (11%, range: 0–54%) after 1,856 revision procedures. Also, Howie et al. (Citation2007) found a high dislocation rate of 14% after 6 years of follow-up. However, in all these studies most of the femoral heads used were 32 mm or smaller. Recent large register studies on primary THAs have shown that the use of larger femoral heads reduces the number of dislocations (Jameson et al. Citation2011, Kostensalo et al. Citation2013). In addition to this, a recent prospective, randomized study by Garbuz et al. (Citation2012) comparing dislocation rates between revision THAs performed using 36-mm and 40-mm heads with those performed with a 32-mm head found a dislocation rate of 1% with 36-mm/40-mm heads and 8.7% with a 32-mm head. Their study was prematurely terminated in light of these stunning findings. Nevertheless, stability advantages in increasing the head diameter beyond 38–40 mm have not been clearly demonstrated (Rodriguez and Rathod Citation2012).

As mentioned earlier, where there is preoperative or intraoperative loss of femoral bone stock, we generally choose to perform femoral bone impaction grafting to reconstruct these defects, combined with a cemented stem (Schreurs et al. Citation2006). Recent studies from several centers have shown that this femoral bone impaction grafting technique can be rewarding in femoral revision cases with bone stock loss (Ornstein et al. Citation2009, Garcia-Cimbrelo et al. Citation2011, Lamberton et al. Citation2011, Te Stroet et al. Citation2012, Garvin et al. Citation2013) (Table 3, see Supplementary data). Excellent survival rates have been reported with re-revision for aseptic loosening as the end point, generally with a survival of greater than 98%. Despite this superior technique, we sometimes choose to perform a cemented revision without bone impaction grafting even in case of extensive femoral bone defects in weak or very old patients. In the current study, 13 of the 92 patients had a preoperative Endoklinik score of 3 or more and would normally have had a bone impaction grafting—but did not get it because of their weak physical condition and/or very old age. No significant differences in the outcomes could be detected between the various Endoklinik groups in our study.

Another promising option for the revision of loose femoral components is the use of uncemented stems. Recent studies of uncemented stems with several different fixation mechanisms have shown survival outcomes ranging from 92% to 100% after medium-term follow-up (Adolphson et al. Citation2009, Muirhead-Allwood et al. Citation2010, Amanatullah et al. Citation2011, Regis et al. Citation2011, Thomsen et al. Citation2013) (Table 3, see Supplementary data). However, possible drawbacks of using these uncemented components are extensive stress shielding (Adolphson et al. Citation2009, Thomsen et al. Citation2013) and subsidence (Regis et al. Citation2011). Long-term results will have to prove whether these findings can lead to complications such as loosening or fractures.

In summary, the results of cemented femoral component revisions show acceptable survival at medium-term follow-up. We recommend the use of this technique in femoral revisions with limited loss of bone stock and in patients who cannot tolerate more extensive surgery with bone grafting due to their physical condition and/or very old age. When a femoral revision must be performed in a younger patient with extensive loss of bone stock, we recommend bone impaction grafting using the instrumented X-change revision system (Schreurs et al. Citation2006, Te Stroet et al. Citation2012).

Supplementary data

Table 3 is available on the Acta Orthopaedica website, www.actaorthop.org, identification number 8203.

MTS designed the study, collected data, analyzed the radiographs, performed statistical analyses, and prepared the manuscript. WHR examined patients, collected data, and contributed with manuscript revision. JWG examined patients, collected data, and contributed with manuscript revision. AVK collected data and contributed with manuscript revision. BWS designed the study, collected data, analyzed the radiographs, and contributed with manuscript revision.

2 of the authors (BWS and WHR) have received an educational grant for instructional course lectures from Stryker-Howmedica (Newbury, UK).

- Adolphson P Y, Salemyr M O, Sköldenberg O G, Bodén H S. Large femoral bone loss after hip revision using the uncemented proximally porous-coated Bi-Metric prosthesis: 22 hips followed for a mean of 6 years. Acta Orthop 2009; 80(1): 14–9.

- Alberton G M, High W A, Morrey B F. Dislocation after revision total hip arthroplasty: an analysis of risk factors and treatment options. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002; 84(10): 1788–92.

- Amanatullah D F, Meehan J P, Cullen A B, Kim S H, Jamali A A. Intermediate-term radiographic and patient outcomes in revision hip arthroplasty with a modular calcar design and porous plasma coating. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26(8): 1451–4.

- Amstutz H C, Ma S M, Jinnah R H, Mai L. Revision of aseptic loose total hip arthroplasties. Clin Orthop 1982; (170): 21–33.

- Brokelman R B, Haverkamp D, van Loon C, Hol A, van Kampen A, Veth R. The validation of the visual analogue scale for patient satisfaction after total hip arthroplasty. Eur Orthop Traumatol 2012; 3(2): 101–105.

- Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A, Murray D. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996; 78(2): 185–190.

- Eisler T, Svensson O, Iyer V, Wejkner B, Schmalholz A, Larsson H, Elmstedt E. Revision total hip arthroplasty using third-generation cementing technique. J Arthroplasty 2000; 15(8): 974–81.

- Engelbrecht E, Heinert K. Klassifikation und Behandlungsrichtlinien von Knochen substanzverlusten bei Revision operationen am Hüftgelenk mittlefristige Ergebnisse. In: Endo-Klinik ed. Primär- und Revisions: alloarthroplastik Hüft-und Kniegelenk. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1987:189–201.

- Fowler J L, Gie G A, Lee A J, Ling R S. Experience with the Exeter total hip replacement since 1970. Orthop Clin North Am 1988; 19(3): 477–89. Erratum in: Orthop Clin North Am. 1989; 20(4): preceding 519.

- Garbuz D S, Masri B A, Duncan C P, Greidanus N V, Bohm E R, Petrak M J, Della Valle C J, Gross A E. The Frank Stinchfield Award: Dislocation in revision THA: do large heads (36 and 40 mm) result in reduced dislocation rates in a randomized clinical trial? Clin Orthop 2012; 470(2):351–6.

- Garcia-Cimbrelo E, Garcia-Rey E, Cruz-Pardos A. The extent of the bone defect affects the outcome of femoral reconstruction in revision surgery with impacted bone grafting: a five- to 17-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93(11): 1457–64.

- Garvin K L, Konigsberg B S, Ommen N D, Lyden E R. What is the long-term survival of impaction allografting of the femur? Clin Orthop 2013; 471(12): 3901–11.

- Gramkow J, Jensen T H, Varmarken J E, Retpen J B. Long-term results after cemented revision of the femoral component in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2001; 16(6): 777–83.

- Haydon C M, Mehin R, Burnett S, Rorabeck C H, Bourne R B, McCalden R W, MacDonald S J. Revision total hip arthroplasty with use of a cemented femoral component. Results at a mean of ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004; 86(6): 1179–85.

- Howie D W, Wimhurst J A, McGee M A, Carbone T A, Badaruddin B S. Revision total hip replacement using cemented collarless double-taper femoral components. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007; 89(7): 879–86.

- Jameson S S, Lees D, James P, Serrano-Pedraza I, Partington P F, Muller S D, Meek R M, Reed M R. Lower rates of dislocation with increased femoral head size after primary total hip replacement: a five-year analysis of NHS patients in England. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93(7): 876–80.

- Kavanagh B F, Ilstrup D M, Fitzgerald R H Jr. Revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1985; 67(4): 517–26.

- Kostensalo I, Junnila M, Virolainen P, Remes V, Matilainen M, Vahlberg T, Pulkkinen P, Eskelinen A, Mäkelä K T. Effect of femoral head size on risk of revision for dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: a population-based analysis of 42,379 primary procedures from the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2013; 84(4): 342–7.

- Lamberton T D, Kenny P J, Whitehouse S L, Timperley A J, Gie G A. Femoral impaction grafting in revision total hip arthroplasty: a follow-up of 540 hips. J Arthroplasty 2011; 26(8): 1154–60.

- Muirhead-Allwood S K, Sandiford N, Skinner JA, Hua J, Kabir C, Walker PS. Uncemented custom computer-assisted design and manufacture of hydroxyapatite-coated femoral components: survival at 10 to 17 years. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010; 92(8): 1079–84.

- Ornstein E, Linder L, Ranstam J, Lewold S, Eisler T, Torper M. Femoral impaction bone grafting with the Exeter stem - the Swedish experience: survivorship analysis of 1305 revisions performed between 1989 and 2002. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009; 91(4): 441–6.

- Pellicci P M, Wilson P D Jr, Sledge C B, Salvati E A, Ranawat C S, Poss R, Callaghan J J. Long-term results of revision total hip replacement. A follow-up report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1985; 67(4): 513–6.

- Raut V V, Siney P D, Wroblewski B M. Outcome of revision for mechanical stem failure using the cemented Charnley’s stem. A study of 399 cases. J Arthroplasty 1996; 11(4): 405–10.

- Regis D, Sandri A, Bonetti I, Braggion M, Bartolozzi P. Femoral revision with the Wagner tapered stem: a ten- to 15-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93(12): 1320–6.

- Rodriguez J A, Rathod P A. Large diameter heads: is bigger always better? J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012; 94 (11 Suppl A): 52–4.

- Schreurs B W, Arts J J, Verdonschot N, Buma P, Slooff T J, Gardeniers J W. et al. Femoral component revision with use of impaction bone-grafting and a cemented polished stem. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88 Supp l1 Pt 2: 259–74.

- So K, Kuroda Y, Matsuda S, Akiyama H. Revision total hip replacement with a cemented long femoral component: minimum 9-year follow-up results. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013; 133(6): 869–74.

- Te Stroet M A, Gardeniers J W, Verdonschot N, Rijnen W H, Slooff T J, Schreurs B W. Femoral component revision with use of impaction bone-grafting and a cemented polished stem: a concise follow-up, at fifteen to twenty years, of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94(23): e1731–4.

- Thomsen P B, Jensen N J, Kampmann J, Bæk Hansen T. Revision hip arthroplasty with an extensively porous-coated stem - excellent long-term results also in severe femoral bone stock loss. Hip Int 2013; 23(4): 352–8.