Abstract

Background and purpose — In hip arthroplasty, acetabular inclination and anteversion—and also femoral stem torsion—are generally assessed by eye intraoperatively. We assessed whether visual estimation of cup and stem position is reliable.

Patients and methods — In the course of a subgroup analysis of a prospective clinical trial, 65 patients underwent cementless hip arthroplasty using a minimally invasive anterolateral approach in lateral decubitus position. Altogether, 4 experienced surgeons assessed cup position intraoperatively according to the operative definition by Murray in the anterior pelvic plane and stem torsion in relation to the femoral condylar plane. Inclination, anteversion, and stem torsion were measured blind postoperatively on 3D-CT and compared to intraoperative results.

Results — The mean difference between the 3D-CT results and intraoperative estimations by eye was −4.9° (−18 to 8.7) for inclination, 9.7° (−16 to 41) for anteversion, and −7.3° (−34 to 15) for stem torsion. We found an overestimation of > 5° for cup inclination in 32 hips, an overestimation of > 5° for stem torsion in 40 hips, and an underestimation < 5° for cup anteversion in 42 hips. The level of professional experience and patient characteristics had no clinically relevant effect on the accuracy of estimation by eye. Altogether, 46 stems were located outside the native norm of 10–20° as defined by Tönnis, measured on 3D-CT.

Interpretation — Even an experienced surgeon’s intraoperative estimation of cup and stem position by eye is not reliable compared to 3D-CT in minimally invasive THA. The use of mechanical insertion jigs, intraoperative fluoroscopy, or imageless navigation is recommended for correct implant insertion.

Failure of cup and stem positioning in hip arthroplasty (HA) can lead to periprosthetic and/or osseous impingement (Trousdale et al. Citation1995), dislocation (Barrack Citation2003, Yoshimine Citation2006), increased component wear (Wan et al. Citation2008), reduced range of motion (Harrison et al. Citation2014), and patient dissatisfaction (Hube et al. Citation2014). Intraoperative estimation of inclination and anteversion of the cup and of femoral stem torsion during HA is usually done by the surgeon visually assessing the cup position relative to the alignment of the patient’s pelvis and visually assessing the stem position relative to the condylar plane of the femur (Zenk et al. Citation2014). Whereas the surgeon has little control of the version of the femoral component in cementless HA, the position of the acetabular component can be varied within the anatomical limits (Bargar et al. Citation2010). Most surgeons still use a defined target area for the acetabular component such as that described by Lewinnek et al. (Citation1978), with a “safe zone” of 40° ± 10° of inclination and 15° ± 10° of anteversion. However, with new concepts it is recommended that the cup and stem should also be positioned in relation to each other (Widmer and Zurfluh Citation2004, Renkawitz et al. Citation2015).

A risk of misinterpretation by visual estimation of stem position intraoperatively has been reported (Wines and McNicol Citation2006). Depending on the positioning of the patient, different landmarks are chosen for orientation intraoperatively (Malik et al. Citation2007). In the supine position, the anterior superior iliac spines (ASISs), the pubic tubercles (PTs), and the femoral condyles are available, with the operation table as reference plane concerning inclination and anteversion. In contrast, with the lateral decubitus position there is a risk of intraoperative movement of the pelvis or tilt of the whole patient during operation process dependent on preoperative settings. Furthermore, the ASISs and PTs may be not accessible due to positioning devices. A comparison between a modified Hardinge approach and a posterior approach showed no difference for the intraoperative estimation of acetabular and femoral component version by eye (Wines and McNicol Citation2006). 3D computed tomography (3D-CT) is the gold standard for reliable measurement of both acetabular and femoral cup position, with a mean accuracy of < 0.5° independently of patient positioning (Craiovan et al. Citation2014).

We posed 2 questions: (1) is the intraoperative estimation of inclination, anteversion, and stem torsion by eye reliable?; and (2) does the surgeon’s visual accuracy correlate with his/her experience or with anthropometric patient data? We therefore evaluated cup and stem position intraoperatively by eye and compared the results to measurements made by 3D-CT.

Patients and methods

During a registered, prospective controlled trial (DRKS 00000739, German Clinical Trials Register) patients underwent HA with or without the use of an imageless navigation device. The current study was a subgroup analysis from a larger cohort (Renkawitz et al. Citation2015). The purpose of the larger study was to assess whether the range of motion of the artificial joint could be improved by computer-assisted, functional optimization of cup position and containment.

Patients admitted for primary cementless unilateral HA (with minimal or no osteoarthritis of the contralateral hip) due to primary or secondary osteoarthritis who were between the ages of 50 and 75 with an ASA score of ≤ 3 were recruited at the Department of Orthopedic Surgery between December 2011 and February 2013. Exclusion criteria were coxarthritis secondary to hip dysplasia, posttraumatic hip deformities, and previous hip surgery. Of 69 patients in the conventionally operated control group without the use of imageless navigation, 1 patient did not receive the allocated intervention—since we had to use an offset liner of +4 mm for sufficient reconstruction of acetabular offset—and was excluded according to the study protocol. Furthermore, 1 patient withdrew his informed consent, refused further participation in the study, and was regarded as a dropout. 1 patient with an incorrect CT protocol was excluded from further analysis, and for 1 patient there was no intraoperative examination of cup and stem position. Thus, 65 patients were included in the final analysis ().

Table 1. Characteristics of the study group (65 patients)

HAs were performed by 4 orthopedic surgeons (JG, ES, MW, and TR) at Regensburg University Medical Center. 2 of them had more than 20 years of professional experience in total hip arthroplasty, and 2 of them had around 10 years. All operations were performed with the patient in lateral decubitus position, through a minimally invasive anterolateral approach to the hip after an intermuscular and interneural tissue plane between the tensor muscle and the gluteus medius muscle (Michel and Witschger Citation2007). During the procedure, the patient was secured with 2 stiff patient positioners on the proximal part of the sacrum and on the symphysis. Press-fit components (Pinnacle; DePuy, Warsaw, IN) and cement-free hydroxyapatite-coated stems (Corail; DePuy) were used. The tribologic pairing consisted of polyethylene liners and metal heads with a diameter of 32 mm. The surgeon intended to place the cup within the target as defined by Lewinnek et al. (Citation1978), with an inclination of 40° ± 10°, an anteversion of 15° ± 10°, and a bony coverage of over 75%. For stem preparation, the medullary canal was reamed using broaches of ascending size until one broach reached a stable position. The stem was inserted in a so-called “best-fitting” position according to the individual patient anatomy. No attempt was made to achieve a particular rotation.

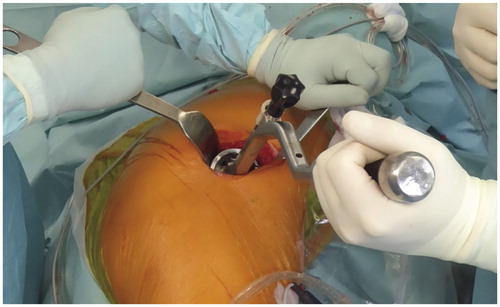

Intraoperatively, inclination, anteversion, and stem torsion were visually assessed by the surgeon. Estimation of stem torsion was performed with the implanted stem in situ by hyperextending the hip dorsally, flexing the knee, and placing the tibia in vertical position while the assistant also identified the 2 femoral epicondyles. The surgeon visualized stem torsion in relation to the posterior axis of the thigh as it bisected the epicondyles. Evaluation and corresponding documentation of inclination and anteversion took place directly after insertion of the final cup. Due to the positioning in the lateral decubitus position, we used the operative definition of cup orientation by Murray in the AP (anterior pelvic) plane as reference (Grammatopoulos et al. Citation2014). The sagittal plane was defined as being parallel to the operating table. The ASISs and PTs were used as visual landmarks. The acetabular axis was defined with the help of the insertion jig of the cup ().

Figure 1. Operation setting with the patient in lateral decubitus position. The flexed insertion jig positions the cup in 45° inclination when its middle rod is brought parallel to the floor.

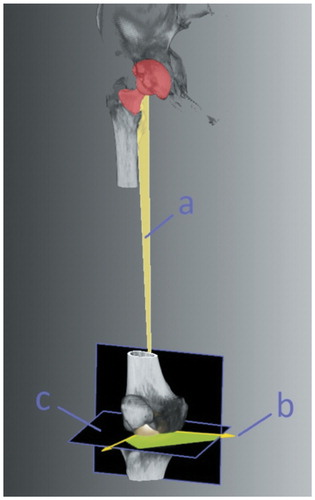

6 weeks postoperatively, a 3D-CT scan was done from the pelvis down to the femoral condyles (Somatom Sensation 16; Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). 3D-CT assessment of acetabular anteversion, inclination, and prosthetic stem torsion was carried out blind by an independent external institution (Fraunhofer MEVIS, Bremen, Germany) (), with measurement by an independent examiner on a 3D reconstruction of the pelvis with image processing software. To calculate the condylar axis, a caudal and dorsal plane of the femoral condyles was defined. The center of the most caudal points of the femoral condyles and the center of the femoral head was used to define the mechanical axis of the femur. A third reference point on the prosthesis was defined. The vector—representing the neck of the prosthesis—was created from this point, pointing towards the center of the femoral head. Then, the normal vector of the plane created from this reference point and both points of the mechanical axis was calculated. With the condylar axis, it was projected onto a plane that was orthogonal to the mechanical axis. The angle between these vectors minus 90° was the femoral stem torsion.

Figure 2. 3D-CT assessment of femoral stem torsion. The mechanical axis of the femur, defined by the center of the most caudal points of the femoral condyles, the center of the femoral head, and the vector, representing the neck of the prosthesis, formed a plane (a) from which a second vector (b) was calculated. With the condylar axis, it was projected onto a plane (c) that was orthogonal to the mechanical axis. The angle between these vectors minus 90° was the femoral stem torsion.

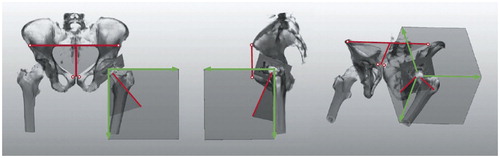

For cup position, 4 landmarks were defined in the anterior pelvic coordinate system: both anterior superior iliac spines (ASISs) and both pubic tubercles (PTs). The frontal pelvis plane was defined by both ASISs and the center of both PTs (). The sagittal pelvis plane was defined as being perpendicular to the frontal pelvis plane. The longitudinal axis was defined by the center of both ASISs and the center of both PTs. Cup inclination and anteversion were calculated according to Murray’s radiographic definition in the AP plane (Murray Citation1993). For comparison of 3D-CT results with the intraoperative estimations of cup and stem position, we converted 3D-CT values from the radiographic definition to the operative definition as defined by Murray (Citation1993). Visual accuracy of component assessment was calculated as the difference between 3D-CT and the corresponding intraoperative estimation by eye. Thus, negative differences represent an intraoperative overestimation, whereas positive values represent a visual underestimation. Overestimation and underestimation were defined as the differences between 3D-CT and the intraoperative assessment by eye of more than 5°.

Figure 3. Schematic depiction of the measurement of inclination and anteversion from a postoperative CT scan. An interactive image segmentation of the surface model was performed. Measurements were calculated by using the AP (anterior pelvic) plane.

Statistics

IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 and the statistical software package R (the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) were used for analysis. The surgeons’ estimations were compared with the results of 3D-CT. We performed a descriptive analysis, calculating means, standard deviation (SD), 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and range to show differences between surgeon’s estimations and 3D CT assessment of acetabular inclination and anteversion and femoral stem torsion. For illustration of the comparison of methods, corresponding Bland-Altman plots are presented.

The degree of correlation between mean intraoperative measurements and 3D-CT measurements was determined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r). Correlation between the mean intraoperative measurement error and BMI, femoral tilt, stem size, cup size, incision length, and grade of osteoarthritis was analyzed in a linear regression analysis. Additionally, BMI was classified into 5 groups according to WHO guidelines (1995): underweight (< 18.5), normal weight (18.5–25), overweight (> 25–30), obese (> 30–40), and severely obese (> 40) (WHO Citation1995). Student’s t-test was used to analyze the association between the mean intraoperative measurement error and stem geometry, treatment side, sex, and the experience of the surgeon. The degree of correlation was described as poor (0.00–0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), good (0.61–0.80), or excellent (0.81–1.00).

Ethics

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (approval number 10-121-0263).

Results

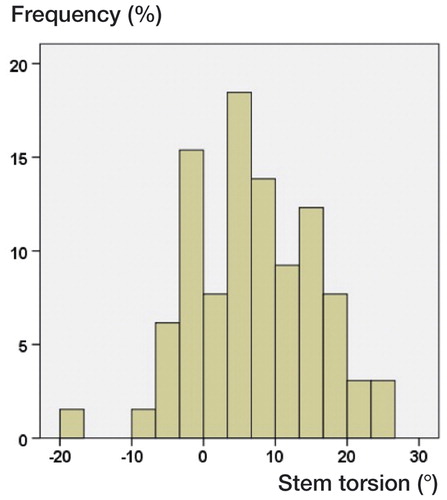

Femoral stem torsion ranged between −19° retrotorsion and 38° antetorsion, as measured on 3D-CT. shows the distribution of femoral stem torsions. Altogether, 46 of the 65 implanted cementless stems were placed outside an interval of 10–20°. Regarding accuracy of cup position, we found a mean difference between 3D-CT measurement and visual intraoperative estimation of −4.9° (SD 5.9; −18 to 8.7) for inclination and 9.7° (SD 11; −16 to 41) for anteversion. For torsion of the femoral component, there was a difference of −7.3° (SD 9.8; −34 to 15) between visual intraoperative estimation and 3D-CT ().

Table 2. Mean values (°) of surgeon’s estimation and CT measurement of acetabular inclination and anteversion and femoral stem torsion

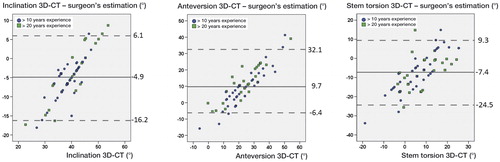

Overall, the Bland-Altman plots of the individual differences of CT measurements and the surgeons’ estimations showed a positive linear correlation regarding cup inclination, anteversion, and stem torsion (). 95% of the individual differences (3D-CT – observer) were located in an interval of −16° to 6.1° for inclination, −6.4° to 32° for anteversion, and −25° to 9.3° for stem torsion. Inclination (r = 0.242; p = 0.05), anteversion (r = 0.309; p = 0.01) and stem torsion (r = 0.236; p = 0.06) showed no clinically relevant correlation between visual estimations and CT measurements of cup inclination, anteversion, or stem torsion. Regarding the distribution of visual component assessment compared to 3D-CT, for cup inclination we found a visual overestimation of over 5° in 32 patients and an underestimation of below 5° in 5 patients of 65, for cup anteversion we found an overestimation in 5 patients and an underestimation in 42 patients of 65, and for stem torsion we found an overestimation in 40 patients and an underestimation in 8 patients of 65.

Figure 5. Bland-Altman plots of the differences between CT measurements and surgeon’s estimations of acetabular inclination (A), acetabular anteversion (B), and femoral stem torsion (C). The continuous line represents the mean difference. Dashed lines show the 95% confidence intervals.

We found a higher (but not statistically significant) deviation in obese patients regarding cup inclination (p = 0.06). No significant correlations were found for BMI and anteversion (p = 0.4) or for BMI and stem torsion (p = 0.5). The level of professional experience had no significant effect on the accuracy of estimating (by eye) stem torsion (p = 0.9; mean for > 10 years of experience: −7.1° (SD 10); mean for > 20 years of experience: −7.5° (SD 8.8)), inclination (p = 0.3; mean for > 10 years of experience: −5.6° (SD 5.1); mean for > 20 years of experience: −4.0° (SD 6.8)), and anteversion (p = 0.2; mean for > 10 years of experience: 8° (SD 12); mean for > 20 years of experience: 12° (SD 10)).

Next, we performed linear regression. Patient chracteristics such as stem size, Kellgren score, length of skin incision, femoral tilt, level of professional experience, and sex had no statistically significant effect on the accuracy of estimation of inclination, anteversion, and stem torsion () by eye. Regarding error of visual estimation of anteversion, we found a statistically significant but not clinically relevant correlation with cup size (r = 0.384; p = 0.03). Similarly, for cup inclination we found a statistically significant but not clinically relevant correlation between the visual accuracy and BMI (r = 0.376; p = 0.008).

Table 3. Variables influencing visual estimation error (linear regression model)

Discussion

We found visual estimation of both cup and stem position intraoperatively to be unreliable in HA, with deviations up to 40°compared to 3D-CT.

The study had some limitations. Firstly, it was restricted to a minimally invasive anterolateral approach in the lateral decubitus position. The visibility of intraoperative landmarks depends on the surgical approach used. Similarly, the reference plane for visual estimation varies according to the position of the patient in relation to the table (Lembeck et al. Citation2005, DiGioia et al. Citation2006, Harrison et al. Citation2014). Thus, the accuracy of visual estimation of cup and stem position may vary depending on the surgical approach. Furthermore, identification of landmarks to identify the AP plane—such as the pubic tubercles—can be challenging, especially in obese patients.

Secondly, we used the operative definition in the AP plane according to Murray (Citation1993) to assess cup position intraoperatively. Since the patients were placed in the lateral decubitus position, we feel that the operative definition is the best method applicable in this setting. The surgeon complies with the sagittal plane and uses the operative definition of anteversion and inclination in relation to the longitudinal axis. The operating surgeons in our study had been familiar with the operative definition and its intraoperative application for many years. However, to ensure comparability with 3D-CT, we had to convert the radiographic 3D-CT position to the operative definition. We re-analyzed our data without that conversion. The deviations between visual estimations and 3D-CT were comparable.

Thirdly, our results rely on the design of a single geometry. Porous-coated press-fit acetabular shells were used with highly crosslinked polyethylene bearings (Bedard et al. Citation2014). The Corail stem anchors on the metaphysis and proximal diaphysis following the anatomic twist and bow of the proximal femoral canal. The best-fitting position of the final stem is therefore a compromise between the implant design and the individual anatomy of the femur. The fixation—and consequently the postoperative stem position—might be different in other stem designs, especially for short and/or anatomic stems. For this reason, the results of our study are restricted to the current stem design, which is, however, one of the most frequently used cementless femoral components in modern HA (with more than 2 million implantations in 2015) (Hallan et al. Citation2007).

We found a deviation between the intraoperative visual estimation and postoperative 3D-CT of up to 18° for cup inclination, 41° for cup anteversion, and 44° for stem torsion. Thus, visual estimation of both cup and stem positon by eye is not reliable in HA. This is comparable to the results of Wines and McNicol (Citation2006), who reported differences between intraoperative, visual estimation and CT of up to 32° for cup anteverion and up to 30° for stem torsion. In the present study, on average we observed an overestimation of 5° for cup inclination, an underestimation of 10° for cup anteversion, and an overestimation of 7° for stem torsion. This indicates that despite the prevalence of outliers, estimation of cup inclination by eye is better than visual assessment of cup and stem anteversion. This is reasonable, since an angle of 45° as the half of a 90° should be easier to obtain than intraoperative evaluation of version angles. Wines and McNicol (Citation2006) reported a mean underestimation of 6° for cup anteversion and a mean underestimation of 1° for stem torsion. The difference, especially in stem torsion, might be due to different surgical approaches. Dorr et al. (Citation2009a) showed a good correlation (0.688) between surgeon estimation of stem torsion (mean 9.6°) and CT measurement (mean 10°) with a posterior approach. Even so, the surgeon’s estimates showed a difference of ± 10° compared to the values of the CT scan.

The linear correlation of the Bland-Altman graphs demonstrates that surgeons tend to estimate both cup and stem position in the middle of the expected “safe zone”; there were no outliers. This means that although the surgeon thinks himself safe, cup and/or stem position may be widely outside the “normal” range.

We found a statistically significant but not clinically relevant correlation between the visual accuracy of evaluating cup inclination and BMI. In the lateral decubitus position, additive soft tissue masses of the leg may have forced the surgeon to implant the cup in higher inclination than intended. Surgeon’s experience, stage of osteoarthritis, and incision length had no impact on the accuracy of intraoperative cup and stem assessment. Even surgical hip experience of more than 20 years did not prevent miscalculation of cup and stem position.

In conclusion, simple visual estimation of cup and stem position during minimally invasive HA is susceptible to error and can lead to component placement outside the intended “safe zones”. The use of intraoperative alignment guides such as mechanical insertion jigs, intraoperative fluoroscopy, or imageless navigation can facilitate the control of cup and stem position in minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty (Sendtner et al. Citation2010). Due to the high variability of cementless stem torsion, we recommend preparing the femur first and adjusting the position of the cup according to the stem following the concept of combined anteversion (Widmer and Zurfluh Citation2004, Dorr et al. Citation2009b).

MW: performed surgeries and data analysis, and wrote manuscript. ES: performed surgeries and data collection. RS: performed data collection and patient management. BC: performed data collection, data analysis, and proofreading. MW: performed data management, patient database, and data collection. TR: performed surgeries and wrote the paper. JG: performed surgeries and proofreading. MW: performed data analysis and data collection, and wrote the manuscript.

The help of Ms S. Kling, Ms C. Jendrewski, Ms M. Riedl, Mr M. Schubert, Mr A. Hapfelmeier, Mr B. Messmer, Mr L. Dohmen, and Dr. M. Haimerl in this project is much appreciated.

None of the authors have financial or any other competing interests related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. Funding for this clinical trial was provided by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF; grant number 01EZ0915). No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

- Bargar W, Jamali A, Nejad A. Femoral anteversion in THA and its lack of correlation with native acetabular anteversion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010; 468: 527–32.

- Barrack R. Dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: implant design and orientation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2003; 11: 89–99.

- Bedard N, Callaghan J, Stefl M, Williams T, Liu S, Goetz D. Fixation and wear with contemporary acetabular components and cross-linked polyethylene at 10-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29: 1961–9.

- Craiovan B, Renkawitz T, Weber M, Grifka J, Nolte L, Zheng G. Is the acetabular cup orientation after total hip arthroplasty on a two dimension or three dimension model accurate? Int Orthop 2014; 38(10): 2009–15.

- DiGioia A, Hafez M, Jaramaz B, Levison T, Moody J. Functional pelvic orientation measured from lateral standing and sitting radiographs. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006; 453: 272–276.

- Dorr L, Wan Z, Malik A, Zhu J, Dastane M, Deshmane P. A comparison of surgeon estimation and computed tomographic measurement of femoral component anteversion in cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009a; 91: 2598–604.

- Dorr L, Malik A, Dastane M, Wan Z. Combined anteversion technique for total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009b; 467: 119–27.

- Grammatopoulos G, Pandit H, da Assunção R, McLardy-Smith P, De Smet K, Gill H, Murray D. The relationship between operative and radiographic acetabular component orientation: which factors influence resultant cup orientation? Bone Joint J 2014; 96(10): 1290–7.

- Hallan G, Lie S, Furnes O, Engesaeter L, Vollset S, Havelin L. Medium- and long-term performance of 11,516 uncemented primary femoral stems from the Norwegian arthroplasty registry. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2007; 89(12): 1574–80.

- Harrison C, Thomson A, Cutts S, Rowe P, Riches P. Research synthesis of recommended acetabular cup orientations for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014; 29(2): 377–82.

- Hube R, Dienst M, von Roth P. Complications after minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. Orthopade 2014; 43: 47–53.

- Lembeck B, Mueller O, Reize P, Wuelker N. Pelvic tilt makes acetabular cup navigation inaccurate. Acta Orthop 2005; 76(4): 517–523.

- Lewinnek G, Lewis J, Tarr R, Compere C, Zimmerman J. Dislocations after total hip-replacement arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1978; 60: 217–20.

- Malik A, Maheshwari A, Dorr L. Impingement with total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89: 1832–42.

- Michel M, Witschger P. MicroHip: a minimally invasive procedure for total hip replacement surgery using a modified Smith-Peterson approach. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2007; 9: 46–51.

- Murray D. The definition and measurement of acetabular orientation. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 1993; 75: 228–32.

- Renkawitz T, Weber M, Springorum R, Sendtner E, Woerner M, Ulm K, Weber T, Grifka J. Impingement-free range of movement, acetabular component cover and early clinical results comparing ‘femur-first’ navigation and ‘conventional’ minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: a randomised controlled trial. Bone Joint J 2015; 97(7): 890–8.

- Sendtner E, Tibor S, Winkler R, et al. Stem torsion in total hip replacement. Acta Orthop 2010; 81: 579–582.

- Trousdale R, Cabanela M, Berry D. Anterior iliopsoas impingement after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 1995; 10: 546–9.

- Wan Z, Boutary M, Dorr L. The influence of acetabular component position on wear in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2008; 23(1): 51–6.

- WHO. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry. Report of a WHO Expert Committee. WHO Technical Report Series 854. World Health Organization 1995.

- Widmer K, Zurfluh B. Compliant positioning of total hip components for optimal range of motion. J Orthop Res 2004; 22: 815–21.

- Wines A, McNicol D. Computed tomography measurement of the accuracy of component version in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2006; 21: 696–701.

- Yoshimine F. The safe-zones for combined cup and neck anteversions that fulfill the essential range of motion and their optimum combination in total hip replacements. J Biomech 2006; 39: 1315–23.

- Zenk K, Finze S, Kluess D, Bader R, Malzahn J, Mittelmeier W. Influence of surgeon’s experience in total hip arthroplasty. Orthopade 2014; 43: 522–528.