Abstract

Background and purpose — Biodegradable cement restrictors are widely used in hip arthroplasty. Like others, we observed osteolytic reactions associated with a specific cement restrictor (SynPlug; made of PolyActive) and reviewed our patients.

Patients and methods — We identified 703 patients with suitable radiographs from our database (2007 to 2012) who underwent cemented hip arthroplasty and received a SynPlug biodegradable cement restrictor. We reviewed all available radiographs to determine the incidence, severity, and progression of osteolysis. Mean postoperative follow-up was 1.8 (1–7) years

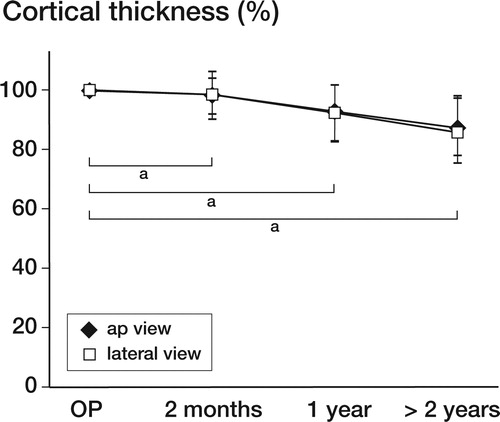

Results — 1 year after implantation, the femoral cortex showed thinning by 12% in the anterior-posterior view and by 8% in the axial view. This had increased to 14% and 12%, respectively, at the latest available follow-up postoperatively (at a mean of 4 years). Cortical thinning of less than 10% was found in 37% of patients, but cortical thinning of 10–30% was found in 56% of patients. In the remaining 7%, a reduction of more than 30% of the original cortical thickness was observed.

Interpretation — Osteolytic changes associated with the SynPlug biodegradable bone restrictors are inconsistent and highly variable. While some patients showed increased weakening of the femoral cortex with the potential risk of periprosthetic fracture, in others the degree of osteolysis only increased slightly or stabilized after 2 or more years. Any cortical bone loss after total hip replacement should be avoided, so the use of PolyActive biodegradable cement restrictors should be discontinued. Patients with a PolyActive cement restrictor in place should be followed up closely after surgery.

Intramedullary plugs are commonly used in cemented total hip arthroplasty (Harris et al. Citation1982, Mulroy and Harris Citation1990). These cement restrictors are available in a wide variety of materials and shapes, both biodegradable and non-reabsorbable (Heisel et al. Citation2003). The use of a biodegradable restrictor has the potential advantage of not requiring removal if revision surgery is required. However, the long-term effects of these biodegradable cement plugs are not fully understood (Waris et al. Citation2008). Foreign-body reactions to biodegradable implants have been described extensively (Weiler et al. Citation2000). These implants can cause a non-specific inflammatory response with invasion of macrophages, leukocytes, and multinucleated foreign-body giant cells (CitationTabata and Ikada 1988, Weiler et al. Citation2000), which can lead to various amounts of osteolytic reaction, as described for a variety of implants and anatomical locations (Böstman Citation1991, Päivärinta et al. Citation1993, Weiler et al. Citation1996, Kwak et al. Citation2008, Waris et al. Citation2008).

During regular follow-up of our patients, we noted early and marked femoral osteolysis around SynPlug cement restrictors (Integra LifeSciences, Plainsboro, NJ; chemical formulation: 1000PEGT70PBT30 (PolyActive)), distal to the cemented prosthesis in a high number of radiographs. Recently, osteolysis around the OptiPlug (Integra LifeSciences)—a biodegradable cement restrictor made of synthetic PEG/PBT copolymer PolyActive (OctoPlus NV, Leiden, the Netherlands) (Dhawan et al. Citation2012, Hanssen et al. Citation2015)—has also been observed. 1 case report identified a fracture due to restrictor-induced osteolysis (Dhawan et al. Citation2012). The material of the OptiPlug is the same as in the SynPlug cement restrictor we used, and differs only in size and shape.

We retrospectively examined radiographs from our patients and determined the incidence of, the time course of, and the amount of osteolytic reaction within the femur after implantation of a SynPlug cement restrictor.

Patients and methods

We identified all patients from our database who underwent hip arthroplasty between 2007 and 2012. We had performed 1,745 total hip replacements during these years, 972 of which were cemented hip arthroplasties. In all cemented hip arthroplasties, we used a SynPlug cement restrictor. Of the 972 patients, we identified 703 who had good-quality radiographs (412 of them women). Patients were excluded from the study if the initial radiograph did not allow adequate measurement of the cortical thickness, or if there was a lack of adequate radiographic follow-up. Mean age at implantation was 75 (44–93) years. In all patients, a fully cemented stem had been implanted (Weber Stem; Zimmer, Baar, Swizerland). In 10 hips a SynPlug restrictor of size 9 was used, in 72 hips size 10 was used, in 293 hips size 12, in 263 hips size 14, and in 54 hips size 16 was used. For 11 patients, the size was not documented. Mean postoperative follow-up time was 1.8 (1–6.6). In 201 patients, the follow-up period was more than 2 years (mean 3.9 (2–6.6) years).

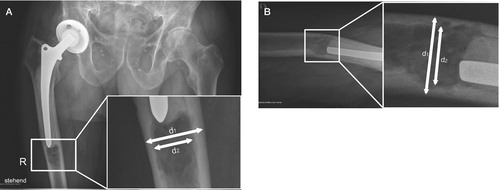

All radiographs that were available were reviewed, and the ratio of the inner to outer cortical thickness around the cement restrictor (both in the anterior-posterior (AP) view and the axial or lateral view) was calculated (). We compared the postoperative ratios with the ratios for the radiographs at 2 months, at 1 year, and at the latest available radiological follow-up after surgery (mean 3.8 years), both in the AP view and the lateral view. Radiographic analysis was performed using the PACS imaging software. The radiographs of patients with a cement restrictor were compared to the radiographs of 100 patients who were operated on after 2012, where a non-biodegradable polyethylene cement restrictor was used (Stuhmer/Weber Plug; Zimmer, Warsaw, IN).

Figure 1. Measurements were performed using the AP view (A) and the lateral view (B). The relationship between inner and outer diameter was calculated from below the tip of the prosthesis. When osteolysis was found, the center of the oval osteolysis was measured.

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 20. Due to the exploratory nature of the trial, no formal sample size calculation was necessary. To obtain valuable estimates of the effect of the SynPlug cement restrictor, we included the complete data pool available from our electronic hospital information system. We used a paired t-test to compare the first postoperative value of cortical thickness ratio to the last available follow-up measurement. All p-values lower than 0.05 were considered to be significant. In order to facilitate the interpretation of cortical thinning, we defined 4 classes: no thinning (< 10%), some thinning (10–20%), moderate thinning (20–30%), and advanced thinning (> 30%).

Ethics

This study was approved (EKSG 13/111) by our local ethics committee.

Results

1 year after implantation, the mean femoral cortex surrounding the cement restrictor showed a thinning of 12% in the AP view (p < 0.01) and 8% in the axial view (p < 0.01). This process of thinning continued slightly over time, to 14% in the AP view and 12% in the axial view at 2 or more years postoperatively (mean 3.9 (2–6.6) years) ().

Figure 2. Graph depicting the amount of loosening over time. After 1 year, a decrease of 8% in both the AP view and the axial view could be observed. At the latest available radiographic follow-up (average 3.9 years), a decrease in cortical thickness of 14% in the AP view and of approximately 12% in the lateral view was found. The osteolytic process appears to be most apparent during the first year, but then it continues at a slower rate. All changes were statistically significant (a p < 0.01).

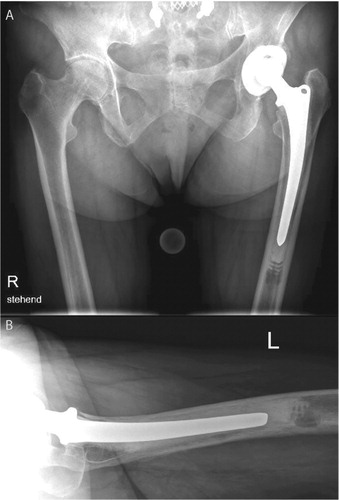

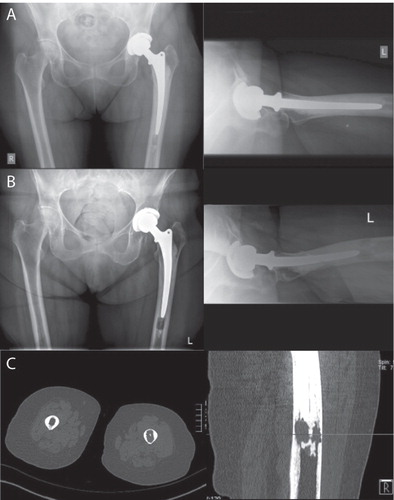

No signs of osteolysis or cortical thinning of less than 10% were found in 37% of the subjects. However, cortical thinning of between 10% and 20% was identified in 34% of patients, and a further 22% of patients showed a reduction of 20–30%. In the remaining 7% of hips, a reduction by more than 30% of the original cortical thickness was observed. We noted that osteolysis was mainly oriented asymmetrically in a sagittal direction, and was therefore first visible on axial radiographs only. Most patients were asymptomatic at the time of radiographic examination, or if symptoms were evident they could not be clearly assigned to osteolytic changes within the femur. However, in an 84-year-old woman (), a clinically symptomatic osteolysis of the femur was present 2 years after surgery. She had been experiencing pain in her mid thigh for approximately 2 months. Due to the large degree of osteolysis and cortical thinning, a protective plate osteosynthesis was suggested, but it was never performed.

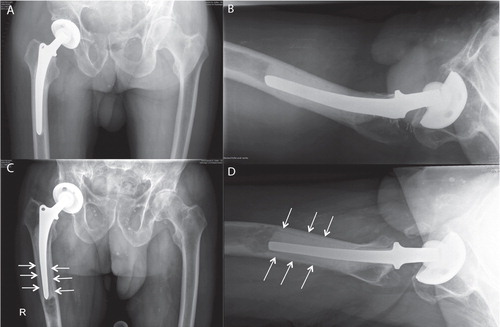

In 2 patients (2 and 5 years after primary surgery), osteolytic changes were accompanied by aseptic loosening of the prosthetic stem ( and ) and stem revision was performed. Interestingly even 5 years after insertion, the remains of the biodegradable cement restrictor could be retrieved; it was fragmented, but still well-preserved. Progressive radiolucency first appeared at the bone-cement interface of the prosthetic stem at the tip of the femoral component, proximal to the SynPlug following osteolytic changes (). In both patients, the cement filling between the tip of the prosthetic stem and the SynPlug cement restrictor was poor.

Figure 3. A 74-year-old woman 4 years postoperatively, in whom osteolysis showed a marked sagittal pattern. In the AP view (A), only minor osteolysis was seen.

Figure 4. A. An 84-year old woman immediately postoperatively with an unremarkable cemented prosthesis. B. 2 years after implantation, a discrete osteolysis was found distal to the prosthesis. C. The amount of osteolysis as seen in a CT. In a standard radiograph, there might be underestimation of the amount of loosening, which we noted often shows in an anterior-posterior pattern, weakening the linea aspera.

Figure 5. A 90-year-old man at 8 weeks (panels A and B) and 7 years (C and D) postoperatively. The images after 7 years (C and D) revealed osteolytic changes in the area of the SynPlug cement restrictor. Progressive radiolucencies first appeared distally around the prosthetic stem just proximal to the osteolytic changes in zone 4.

Interestingly, analysis of radiographs of 100 recent patients (after 2012), where a non-biodegradable cement restrictor had been used and the same prosthetic components had been implanted revealed no osteolysis in both planes on AP and axial radiographs.

Discussion

We found a high amount of osteolysis associated with a widely used material for cement restrictors (SynPlug, 1000PEGT70PBT30 PolyActive) in hip arthroplasty. PolyActive is a segmented copolymer of polyethylene oxide tetraphthalate and polybutyleneterephthalte (PEO/PBT). The material has proven to be biocompatible and osteoconductive, and it appears to be a bone-bonding material, particularly if the PEO content is 55 mol% or higher (Radder et al. Citation1994b,Citation1995,Citation1996, Meijer et al. Citation1996, Kuijer et al. Citation1998, Sakkers et al. Citation2000). The higher the PEO/PBT ratio, the more rapid the mineralization and calcification of the interface can be observed (Radder et al. Citation1994a). The best results were achieved with a 70/30 ratio, which is the ratio of PolyActive (SynPlug). The flexibility and hydrogel properties have made this biomaterial favorable for occlusion of the femoral canal, even in oval and irregular shapes (Bulstra et al. Citation1996). The hydrophilic properties of the PolyActive composition chosen for SynPlug cement restrictors allows the material to expand after implantation. The swelling characteristics of PolyActive have been considered to be an important factor in creating a strong interface bond between polymer and bone (Radder et al. Citation1994b,Citation1995; Sakkers et al. Citation2000). Biodegradation is thought to occur from a combination of hydrolysis and oxidation. The potential benefit—elimination of the need for restrictor removal at future revision surgery—led to our use of SynPlug. Bulstra et al. (Citation1996) first tested the PolyActive material for use in cement restrictors in a pilot clinical trial involving 21 patients. No local changes in the femur were observed. In contrast, we found obvious adverse reactions to this material.

The osteolytic reactions observed varied between patients. Apart from the 2 patients with painful loosening of the prosthetic stem and 1 patient with extensive osteolytic changes, the vast majority of patients had no symptoms that could be assigned to osteolytic changes. Asymptomatic osteolysis of the femur associated with PolyActive cement restrictors has been reported earlier (Ockendon et al. Citation2011, Hanssen et al. Citation2015). There is no explanation as to why some patients develop a higher degree of osteolysis than others, and the timeline until the osteolytic process is complete is not predictable. It appears that in most cases the process of osteolysis is mainly active during the first 2 years after implantation. However, in some patients extensive osteolysis was first observed 5 years after surgery, which suggests that the process continues over time.

In an experimental study, Waris et al. (Citation2008) used elastomeric stems made of PolyActive to anchor polylactate joint scaffolds for the reconstruction of metacarpophalangeal joints in minipigs. PolyActive caused extensive osteolytic lesions and massive foreign-body reactions. The foreign-body reactions persisted until 1 year, but they gradually settled down until the end of the 3-year follow-up. Ockendon et al. (Citation2011) performed a retrospective, radiographic analysis of 100 patients where an OptiPlug cement restrictor (equivalent to SynPlug, and also manufactured from PolyActive) had been used. 87 of the radiographs showed more than 10% thinning of the cortex 1 year postoperatively, and 5 showed more than 33% thinning, but the osteolytic changes did not appear to progress or regress between 1 and 5 years. Dhawan et al. (Citation2012) described a patient who sustained a periprosthetic fracture due to PolyActive cement restrictor-induced osteolysis 5 years after surgery.

Most of the osteolytic lesions that we observed were asymmetric, and showed a sagittal orientation, extending into the posterior part of the femur and the linea aspera. It is difficult to predict the fracture risk in patients with lytic lesions, but it has been shown that the size of lytic lesions alone is a predictor of fracture (Snyder et al. Citation2006). Other critical parameters that determine the strength of a bone carrying a lytic lesion include the amount of bone loss, the properties of the remaining bone tissue, the cross-sectional geometry and location of the lesion, and the loading mode (Hipp et al. Citation1995, Whealan et al. Citation2000). The amount of osteolysis that is needed to cause a fracture appears to be rather large, which could explain why patients with extensive osteolysis remain asymptomatic. To date, we have not seen an associated periprosthetic fracture in our series.

Osteolysis and loosening in hip prosthetics is generally thought to be caused by small wear particles, as is often shown in the acetabular component (Dumbleton et al. Citation2002). In our patients, we observed an atypical loosening pattern. The radiolucences started distally at the tip of the femoral component (Gruen zone 4) and continued proximally and not vice versa—as we would expect for polyethylene wear. We suggest that a process similar to that described for polyethylene wear might happen at the distal end, if a biodegradable cement restrictor is used. Perhaps the degradation of biomaterials triggers an osteolytic reaction. It has been reported that the fragments released from the degradation of the biodegradable material are phagocytosed by macrophages, which leads to the death of the macrophages—leading to a further inflammatory response (CitationTabata and Ikada 1988). This could possibly explain radiolucences, starting from distal to proximal.

It might be that the incidence of loosening of the prosthetic stem correlates with poor cementing technique. In the 2 patients in whom loosening of the prosthetic stem associated with SynPlug osteolysis was observed, the tip of the prosthesis was not well covered with cement. It could be hypothesized that a well-cemented interface between the tip of the prosthesis and the cement restrictor might prevent ascending osteolytic changes. However, we found no correlation between finding prostheses that were caudally not covered with cement and the amount of osteolytic reactions.

We have therefore decided to follow our patients regularly, especially those patients who exhibited a large amount of osteolysis (more then 20% of the cortical thickness) during the first review.

Our study had several limitations. The follow-ups were inconsistent and relatively short. Patients were reviewed routinely at 2 months, 1 year, 5 years, and 10 years after hip prosthesis surgery. For the elderly patients, follow-ups were often arranged by the family doctors. These cases and patients with bad-quality radiographs (269 of 972) had to be excluded from the study.

It still remains unclear how osteolysis develops over time, especially after 5 years. The osteolytic fracture 5 years postoperatively due to the use PolyActive described in the literature (Dhawan et al. Citation2012) and also the results of the present study should encourage clinicians to arrange long-term follow-up of more than 5–10 years.

We suggest abandoning use of the biodegradable SynPlug cement restrictor in cemented hip arthroplasty due to the potential risk of osteolysis and subsequent periprosthetic fracture or aseptic loosening.

No competing interest declared.

All the authors were involved in the design of the study. Data management and analysis were undertaken by ME, VZ, and KG, and JE and CO contributed to interpretation of the data. All the authors contributed to preparation of the manuscript.

- Böstman O M. Osteolytic changes accompanying degradation of absorbable fracture fixation implants. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1991;73(4):679–82.

- Bulstra S K, Geesink R G, Bakker D, Bulstra T H, Bouwmeester S J, van der Linden A J. Femoral canal occlusion in total hip replacement using a resorbable and flexible cement restrictor. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996; 78(6): 892–8.

- Dhawan R K, Mangham D C, Graham N M. Periprosthetic femoral fracture due to biodegradable cement restrictor. J Arthroplasty 2012; 27(8): 1581 e13–5.

- Dumbleton J H, Manley M T, Edidin A A. A literature review of the association between wear rate and osteolysis in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2002; 17(5): 649–61.

- Hanssen N M, Schotanus M G, Verburg A D. Osteolysis in cemented total hip arthroplasty involving the OptiPlug cement restrictor: more than an incident? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2015; 25(1): 45–51.

- Harris W H, McCarthy J C, O’Neill D A. Femoral component loosening using contemporary techniques of femoral cement fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1982; 64(7): 1063–7.

- Heisel C, Norman T L, Rupp R, Mau H, Breusch S J. Stability and occlusion of six different femoral cement restrictors. Orthopade 2003; 32(6): 541–7.

- Hipp J A, Springfield D S, Hayes W C. Predicting pathologic fracture risk in the management of metastatic bone defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995; (312): 120–35.

- Kuijer R, Bouwmeester S J M, Drees M M W E, Surtel D A M, Terwindt-Rouwenhorst E A W, Van Der Linden A J, et al. The polymer Polyactive® as a bone-filling substance: An experimental study in rabbits. J Mater Sci Mater Med 1998; 9(8): 449–55.

- Kwak J H, Sim J A, Kim S H, Lee K C, Lee B K. Delayed Intra-articular inflammatory reaction due to poly-L-lactide bioabsorbable interference screw used in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthrosc - J Arthrosc Relat Surg 2008; 24(2): 243–6.

- Meijer G J, van Dooren A, Gaillard M L, Dalmeijer R, de Putter C, Koole R, et al. Polyactive as a bone-filler in a beagle dog model. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1996; 25(3): 210–6.

- Mulroy R D, Harris W H. The effect of improved cementing techniques on component loosening in total hip replacement. An 11-year radiographic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1990; 72(5): 757–60.

- Ockendon M, Oakley J E, Graham N M. Osteolysis associated with optiplug bioabsorbable cement restrictors. J Bone Joint Surg 2011; 93-B(SUPP IV): 547–7.

- Päivärinta U, Böstman O, Majola A, Toivonen T, Törmälä P, Rokkanen P. Intraosseous cellular response to biodegradable fracture fixation screws made of polyglycolide or polylactide. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1993; 112(2): 71–4.

- Radder A M, Davies J E, Leenders H, van Blitterswijk C A. Interfacial behavior of PEO/PBT copolymers (Polyactive) in a calvarial system: an in vitro study. J Biomed Mater Res 1994a; 28(2): 269–77.

- Radder A M, Leenders H, van Blitterswijk C A. Interface reactions to PEO/PBT copolymers (Polyactive) after implantation in cortical bone. J Biomed Mater Res 1994b; 28(2): 141–51.

- Radder A M, Leenders H, Van Blitterswijk C A. Bone-bonding behaviour of poly(ethylene oxide)-polybutylene terephthalate copolymer coatings and bulk implants: A comparative study. Biomaterials 1995; 16(7): 507–13.

- Radder A M, Leenders H, Van Blitterswijk C A. Application of porous PEO/PBT copolymers for bone replacement. J Biomed Mater Res 1996; 30(3): 341–51.

- Sakkers R J B, Dalmeyer R A J, De Wijn J R, Van Blitterswijk C A. Use of bone-bonding hydrogel copolymers in bone: An in vitro and in vivo study of expanding PEO-PBT copolymers in goat femora. J Biomed Mater Res 2000; 49(3): 312–8.

- Snyder B D, Hauser-Kara D A, Hipp J A, Zurakowski D, Hecht A C, Gebhardt M C. Predicting fracture through benign skeletal lesions with quantitative computed tomography. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006; 88(1): 55–70.

- Tabata Y, Ikada Y. Macrophage phagocytosis of biodegradable microspheres composed of L-lactic acid/glycolic acid homo- and copolymers. J Biomed Mater Res 1988; 22(10): 837–58.

- Waris E, Ashammakhi N, Lehtimäki M, Tulamo RM, Törmälä P, Kellomäki M, et al. Long-term bone tissue reaction to polyethylene oxide/polybutylene terephthalate copolymer (Polyactive®) in metacarpophalangeal joint reconstruction. Biomaterials 2008; 29(16): 2509–15.

- Weiler A, Helling H J, Kirch U, Zirbes T K, Rehm K E. Foreign-body reaction and the course of osteolysis after polyglycolide implants for fracture fixation: experimental study in sheep. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996; 78(3): 369–76.

- Weiler A, Hoffmann R F, Stähelin A C, Helling H J, Südkamp N P. Biodegradable implants in sports medicine: the biological base. Arthroscopy 2000; 16(3): 305–21.

- Whealan K M, Kwak S D, Tedrow J R, Inoue K, Snyder B D. Noninvasive imaging predicts failure load of the spine with simulated osteolytic defects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82(9): 1240–51.