Abstract

Traditionally, continuing medical education (CME) activities were delivered on a country-by-country basis with very little expansion across borders. With a strong belief in the globalisation of medicineCitation1, the expansion of educational activities to other countries or regions has become of great interest for medical education providers, associations and pharmaceutical companies. While language barriers and accreditation requirements are widely respectedCitation2, with several publications accessibleCitation3Citation4, very little attention has been paid to differences in the medical education pathways and underlying national health care systems—potentially leading to different learning styles and learning needs. In order to address this question, the following research project was documented and analysed based on a structured questionnaire on three main aspects of under- and postgraduate education and continuing medical education (CME) in 12 European countries: 1. Terminology: Increased understanding of terminology applied beyond language barriers, for example, do we mean the same when using the same term? 2. CME systems: Detailed documentation on national CME requirements, including review of impact for physicians, for example, the implications of stated requirements as well as roles and responsibilities. 3. Medical education pathways: Documentation of the medical education pathway from undergraduate to postgraduate and life-long learning, including how CME is embedded in this pathway as well as underlying structures. Field research was performed from October 2010 till October 2011 by native speakers with a medical or pharmaceutical background. It revealed significant differences in all areas analysed with subsets of countries following similar models. Bearing in mind the objective of offering best quality in response to learners’ needs, this research project may serve as a relevant source for providers of medical education and medical societies when developing educational programmes for their members as well as for the set-up of global projects and collaboration. In addition, the information gathered and analysed may serve as an interesting resource for CME professionals in various positions. The next step will be to analyse the impact of integrating this knowledge into the educational planning process for national and international projects and to assess if this will prove to be an additional quality factor for educational programmes and will improve outcomes.

Introduction

The need for a broader perspective of continuing medical education (CME) systems and accreditation requirements is widely accepted when designing educational programmes (2). Specifically, European Union of Medical Specialists/European Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (UEMS-EACCME) and other stakeholder groups provide in-depth information on the structure of CME requirements in EuropeCitation3,Citation4. Nevertheless, knowledge of accreditation requirements may not be enough to ensure that projects meet the learners’ needs, especially when going beyond regional and/or country borders.

While different languages and differences in culture have been accepted as potential barriers (that may be resolved by customisation and translation of the material), very little attention has been paid to differences in understanding.

A discussion on LinkedIn in 2010Citation5 showed interesting differences in the understanding and application of the terms ‘accredited’, ‘certified’, ‘CME’ and ‘non-CME’ while each participant was sure that his/her terminology was the right one!

Very little effort has been undertaken so far to better understand the different roles and responsibilities during the medical education pathway from medical school/university to postgraduate specialisation and life-long learning (CME).

Integrating a more comprehensive knowledge of the learners’ educational understanding, history and environment into the educational planning process may prove to be an additional quality factor and substantially improve outcomes of educational projects – on a local level as well as for international projects and expansions.

Research methodology and objectives

The research project was initiated in October 2010 by the European Institute of Medical & Scientific Education (EIMSED) and implemented in cooperation with White Cube Health Care between October 2010 and October 2011.

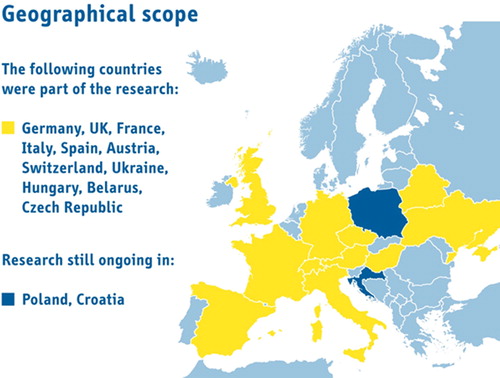

Field research took place in 13 European countries; to date, 11 have been completed and analysed ().

In a consolidated, structured approach, a detailed database was developed for these countries through Internet research on national health care systems (medical school system, specialisation system and postgraduate educational system), complemented by standardised interviews with different stakeholders based on a predetermined questionnaire. Research and interviews were performed by native speakers of the different countries, all fluent in German and their mother tongue with a medical or pharmaceutical background. Stakeholder groups consisted of physicians, representatives from national and local physician associations and chambers, medical colleges and health care authorities.

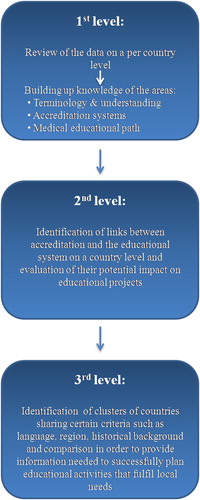

The goal of this research was to provide a comprehensive understanding of three main aspects of national medical education systems from undergraduate to postgraduate and continuing medical education across Europe as well as to assess the need for translating this knowledge into action in the educational planning process with regard to educational quality and best practice.

Terminology and understanding: Are there differences in terminology applied – beyond language barriers – that may lead to misunderstandings for cross-border activities?

In order to answer this question, frequently used terms such as accreditation, certification and validation were analysed with regard to their meaning in the respective country. In addition, the research covered in detail the basic definitions and requirements for CME.

Accreditation systems: How important is it to know the specific details within the accreditation system of each individual country? Do we know structures and responsibilities?

The research covered general information about the rules and regulations regarding CME in the respective country as well as detailed information regarding the regulatory framework.

Educational pathway from university to postgraduate education: Do we know the educational background of the learner and its impact on learning styles and needs? Do we know structures involved and responsibilities? How is CME positioned within this setting?

The core of the research project was a detailed analysis of how medical education is structured in the different countries as well as the discussion on how this may impact learners’ needs.

In addition a full set of contacts and further references per country was developed The complete dataset has been compiled in a comprehensive compendium by EIMSED.

Results

Terminology and understanding

The research project revealed many differences in terminology and understanding of respective terms, very often only identified when looking into the details. Terms used for describing CME and CME-related subjects differ critically across the analysed countries, even if the language is the same. The same terms are used with different meanings or different terms mean the same (), for example:

Table 1. Terminology and understanding - Different meanings of ‘accreditation’, ‘certification’, ‘approval’, ‘approbation’ and ‘licensure’ in the analysed countries

Accreditation

While in Germany and Austria (like in the United States [US]), the term ‘accreditation’ means the recognition of the provider of continuing education, it is used only for the recognition of CME programmes in Hungary. In Italy and Spain ‘accreditation’ means recognition of the provider as well as recognition of CME programmes. In Switzerland, Ukraine, Belarus and Czech Republic (as well as in the United Kingdom [UK] where ‘approval’ is the correct term for the recognition of educational programmes even though ‘accreditation’ is understood and used), the term is not used at all in relation to CME providers or programmes. Universities in Ukraine and Belarus can get ‘accreditation’ by the Ministry of Health and are then allowed to offer education, continuing education and qualification activities.

Accredited providers in their respective countries are allowed to recognise their own activities. In France, the term ‘accreditation’ is not used in the context of CME, but physicians and health personnel could be voluntarily accredited within the scope of EPP (Evaluation des pratiques professionelles) as a seal of quality. To describe recognition of providers of continuing education, the French use the term ‘agréement’.

In Hungary, this term means recognition of single events, and the provider of those events has to be ‘validated’ by a medical university.

Certification

The term ‘certification’ or ‘certified’ is mainly used in Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic to describe the recognition of CME activities, although the more common term in Austria is ‘approbiert’ (see below). In all other countries, ‘certification’ is used in different settings such as recognition of a medical facility or medical personnel.

In contrast, ‘certification’ is not used in the context of CME in France. There, ‘certification’ of medical facilities, like ‘accreditation’ of medical personnel and physicians, is a part of EPP. In the United Kingdom (UK), the term ‘certification’ is used if a physician has successfully completed post-graduate training and ‘recertification’ means a regular confirmation of the physician's quality standards.

Approval

In the UK and in Switzerland, where ‘accreditation’ is not officially used for the recognition of continuing education providers or activities, the term ‘approval’ is used to describe those recognition processes.

Licence

Various terms are being used to describe a physician's permit to practise independently with additional specification related to this permit:

While in the UK, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Ukraine and Belarus, physicians have to renew their permit on a regular basis; physicians in Germany, France, Italy, Austria, Switzerland and Spain do not have this obligation.

‘Licence’ as a term to describe the authorisation to practise is only used in the UK, Switzerland, the Czech Republic and Spain whereas in Hungary, Ukraine and Belarus a ‘licence’ is provided to medical facilities.

In Ukraine and in Belarus, the term ‘1.Attestation’ corresponds to the English term licence, while in Germany the term ‘Approbation’ is the corresponding term.

In Austria, the German term ‘Approbation’ has a completely different meaning: Here ‘Approbation’ stands for the recognition of CME activities by an accredited provider which are then called ‘DFP-certified CME activities’.

The table below summarises:

a) the meaning of the respective term per country

b) the corresponding term per country in local language.

CME-system

In all of the analysed countries, there exists a moral or ethical obligation for physicians continuously to update their medical knowledge – independent of mandatory or voluntary systems – but there were significant differences in the execution ().

Table 2. Credit-based CME systems in Europe

Roles and responsibilities

Different models were found in the roles and responsibilities of the different stakeholders for the different countries:

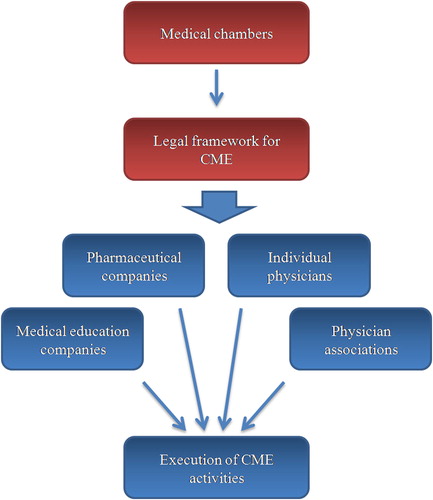

Model 1: The physician-centric model

In the physician-centric model, CME is independent of the educational system of the country and is governed by physician representatives (chambers, unions, associations, scientific societies, medical colleges) (). The typical country for this model is Germany, but also Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Czech Republic and the UK (with some significant differences) follow this model. In these countries, the medical chambers (Germany, Austria, Italy, Czech Republic) or associations/colleges (Switzerland, UK) are responsible for the management of CME activities, including, certification of CME activities, accreditation of providers (where applicable) and tracking of compliance with the framework. In some of these countries, the professional associations are also responsible for the provision of the legal framework; in some of them, this stays within the responsibility of the ministry of health.

From country to country, the execution of CME activities is done by various groups, which may include medical education companies, pharmaceutical companies, physician associations, national scientific societies and individual physicians ().

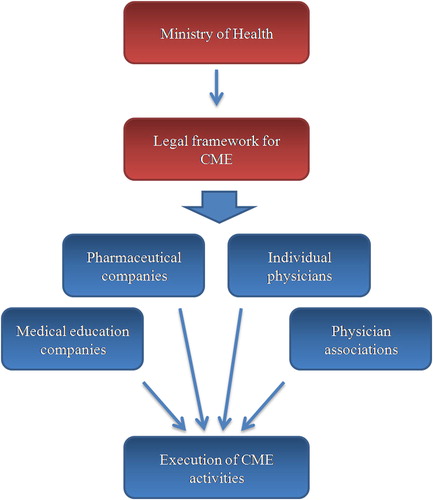

Model 2: The politician-centric model

In the politician-centric model, CME is independent of the educational system but the provision of the legal framework lies within the hands of the Ministry of Health and not in the hands of physician entities such as physician medical chambers and physician associations/societies (). The execution is – like the physician-centric model – provided by various stakeholders (representive countries for this model are France and Spain). Italy currently faces a unique situation in having models 1 and 2 implemented at the same time while moving from a decentralised approach with the medical chambers being the primary decision-makers for programme certification and provider accreditation (model 1) to a more centralised approach with the ministry of health and its agencies being responsible provider accreditation.

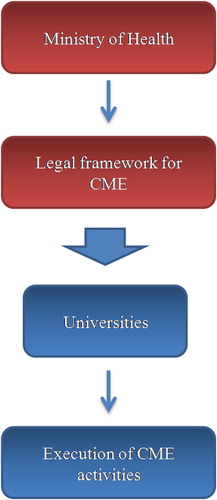

Model 3: The university-centric model

This model shows significant differences to models 1 and 2 in which there is a clear-cut distinction between undergraduate medical education and CME with the execution being provided by various stakeholders. CME in model 3 is an integral part of the medical education pathway with universities as the dominant or single provider of CME while the legal framework is provided by the Ministry of Health (Hungary, Ukraine, Belarus) ().

Accreditation system and regulation of CME

In the majority of European countries, CME has become mandatory (Austria, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy and Switzerland) with only few countries detailing sanctions in case of non-compliance (Germany, Hungary and Switzerland). In Spain, Ukraine and the UK, CME is voluntary—with detailed sanctions in cases on non-compliance in the Ukraine (loss of licence on the basis that continuing education is an ethical obligation for physicians).

Medical education pathway

In all of the analysed countries, medical schools and universities are responsible for medical education until graduation. However, there are significant differences about when a physician receives his/her medical licence as well as how CME (life-long learning) is embedded in the overall medical education system ().

In Germany, medical students begin their medical education with a six-year study at a medical university, including 48 weeks of practical education. After obtaining their ‘Approbation’, the doctors-to-be start with their postgraduate education under the responsibility of the state chamber of physicians, which is clearly separated from medical school. On average, specialist training in Germany lasts five years and ends with the right to hold the respective specialist title. Since 2003, every statutory health insurance physician needs a post-graduate qualification to open a medical office. Germany is characterised by a large number of specialists working in private offices within the national health care system, and patients are free to see a specialist directly, even though the insurance companies try to support the gatekeeper role of GPs through incentives.

In France, medical education is divided into three parts, in which part one and part two take place at a medical university with a standard period of study of six years. Part three that also includes specialist training lasts three years for GPs and five years for other specialities and takes place in designated hospitals. After completion of specialist training, the physicians obtain their DES (diploma d'etudes de specialist). As in Germany, patients in France are allowed to see a specialist directly instead of first having to visit their GP, but insurance companies also try to support the gatekeeper model through incentive systems for the patients.

Medical education in the UK is divided into two parts. Part one takes place at a medical school and finishes with the degrees of bachelor of medicine and surgery; part two is a so-called ‘foundation’ programmes at a teaching hospital. The foundation programmes is under the responsibility of the GMC and lasts two years: at the end of year one, they obtain their full GMC registration and their licence. Afterwards physicians have to complete their specialist training, a requirement for practising within the National Health Service (NHS). The specialist training in the UK is under the responsibility of the Royal medical colleges, lasts three to five years and at the end, the physicians have to register on the GMC specialist register or GMC GP register.

Medical education in Spain is divided into two parts: At the beginning medical students have to finish a six-year period of study at a medical university with the degree ‘grado academic’ = ‘Licenciado in Medicina’, which corresponds with the ‘Approbation’ in Germany or the DES in France. Following university, the physicians can begin their specialist training as MIR (medico interno residente) at an accredited hospital. A physician’s specialist designation is dependent on the results of the ‘grado academico’. In Spain, the majority of specialists work in hospitals or at health centres.

In Italy, medical education has a similar structure to Spain. It is divided into a six-year period of study at a medical school, which results in registration at the medical chamber and the licence to practise. Then the doctors begin their specialist training, which lasts three years for GPs. Since 2000, in most regions of Italy (e.g. Venetia) every statutory health insurance physician needs a postgraduate qualification to open a medical office.

The similarity of the three countries analysed above (the UK, Spain, Italy), in contrast to Germany and France, is that GPs have a clear gatekeeper role and are responsible for deciding whether a consultation with a specialist is necessary.

At the beginning of medical education in Austria, medical students have to undergo six years of study at a medical university. After graduation, they get their ‘Arztdiplom’. Subsequently the doctors start their post-graduate training as ‘Turnusarzt’, which lasts three years for GPs or six years for other specialities. In contrast to most other European countries, Austrian physicians get their licence to practise only after postgraduate training. As in Germany or most parts of Italy, statutory health insurance physicians need a GP/specialist title to open a medical office. Austria has, traditionally, a hospital-centred health care system with the highest amount of hospitalisation across Europe, but with the shortest periods of hospitalisation.

Medical education in Switzerland is similar to Austria. Initially, medical students have to go to a medical school for six years, which ends with the ‘Arztdiplom’. Afterwards they have to undergo their obligatory three to five years of specialist training, which ends with the right to practise independently. In Switzerland, there exist voluntary gatekeeper models, so-called HMOs (health maintenance organisation) where the patient is committed to see only doctors from his/her HMO. If the patients are not organised in such a system, they are free to choose their doctors.

In the Ukraine, universities get an accreditation by the explain MOZ to offer medical education, qualification and continuing education. Universities also have to request a licence, which is subject-related, not individual-related. Medical education is divided into three parts: It begins with six years of study at an accredited university. A clinical part follows, which ends with specialist training and the title ‘Likar-Spetsialist’, which correlates with the ‘Approbation’ in Germany or the licence in the UK.

In Hungary also, medical education begins with a six-year study at a medical university. After successful completion of medical school, students get their doctoral degree and their registration from the university. Subsequent to university, the doctors have to undergo a 26 period of ‘Residenz’. Following the ‘Residenz’, the physicians can begin their mandatory one to four years of specialist training, which ends with the right to practise. In Hungary and in Ukraine, all medical services are provided through policlinics/‘physicians houses’. Another similarity of both countries is that undergraduate and postgraduate degrees are centralised, with universities playing the central role.

Discussion

Significant differences were found between European countries in relation to terminology applied, to the course of the educational pathway of a physician, the manner in which CME is embedded with this educational pathway, to the roles and responsibilities of the various stakeholders and, last but not least, to the underlying structures. The differences of CME accreditation systems discussed above were only one aspect that stemmed from underlying more complex systematic differences.

The differences in terminology reflect systematic and significant difference in positioning of CME as well as cultural or political differences.

While all countries analysed require a moral or ethical obligation for physicians continuously to update their knowledge, significant differences were revealed in the execution – showing that it is not enough to know in which country CME is mandatory (majority of countries) and where it is voluntary (the UK, Ukraine, Spain). The meaning of mandatory versus voluntary varies significantly from country to country. CME, for example, is mandatory in Italy, but no sanctions or consequences are described in case of non-compliance. In contrast, in the Ukraine, CME is voluntary but in the case of non-fulfilment of the detailed education plan, the physician will lose his or her licence and has to repeat not only the final exam but also the last internship!

Significant differences between the so-called western European countries and the former eastern European countries (Hungary, Ukraine, Belarus, Czech Republic) were found in the way CME is embedded within the educational pathway, and the roles and responsibilities of universities in CME – reflecting the different political environment.

In the majority of western European countries, a significant distinction is found between well-structured undergraduate education provided by medical schools and universities and more or less unstructured approaches to CME, depending on the personal interest of the physician without any validation or feedback mechanisms. In these systems, universities play no role in CME, neither in providing framework or educational knowledge nor in set-up and execution of educational programmes. If at all, they act as CME providers on a local level. In contrast in the former eastern European countries, especially the representatives of the former Soviet Union, CME is an integral part of the educational pathway with the universities as the central providers of undergraduate education, specialisation and postgraduate education, based on an educational programme with mandatory and optional elements. Taking all this into account, it is not surprising that it is an eastern European country that uses the term ‘life-long learning’ for CME.

Conclusions

For the first time, this research has enabled us to establish a comprehensive data base of prevailing CME systems, medical education pathways, and roles and responsibilities of the various stakeholders was built up, which we consider mandatory knowledge for the development and implementation of successful educational programmes that add value to the learner.

Our research revealed significant structural and systematic differences in the medical education systems as well as in the understanding and impact of stated CME requirements. However are these findings relevant to the development of educational programmes? The authors of this article share the strong belief that the answer is yes, even though this research project was not set up to provide statistical significance for this hypothesis.

Approach and expectations of the learner for CME programmes will be very different depending of the medical education system they come from – as will be their reactions to certain learning styles. Learners coming from a very structured, ‘school-based’ system will be challenged by interactive, less structured programmes or programmes where the learner is in the driving seat.

The identified structural and systematic differences support the need not only to know the accreditation requirements at national level and to address them in the development of programmes. They must also be familiar with the CME providers as well as other CME professionals (including the industry) fully to understand these differences. They must use their knowledge during the educational planning process in order to provide value to the learner. A high-quality educational programme must not only fulfil the accreditation requirements of a specific country but must take into account how the learner is accustomed to learn, who are the relevant partners and stakeholders in the country and the providers should understand the environment where the learner practises in order positively to impact on patient care.

The next step will be to broaden this knowledge to more countries in the hope that its integration in educational programmes will influence motivation and willingness to learn and thereby create positive learning outcomes. Another interesting aspect will be to include cultural differences in the analysis.

Declaration of Interest

Funding

This study was funded by EIMSED.

Author(s) Financial Disclosure

I.W. has disclosed that she is a consultant/advisor for EIMSED.

M.S. has disclosed that she has no relevant financial relationships.

I.S. has disclosed that she has no relevant financial relationships.

Peer reviewers(s)

Peer Reviewer 1 has disclosed that he/she has no relevant financial relationships.

Peer Reviewer 2 has disclosed that he/she has no relevant financial relationships.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank our research team for the dedicated work they provided: Isabella Stapff, Olga Krvtsova-Dotzauer, Franziska Törk and Agnes Takacs.

Part of the data from this study was previously presented as an oral presentation at the 16th Annual meeting of the Global Alliance for Medical Education, June 7, 2011, Munich, Germany.

All details of the research have been compiled in a comprehensive compendium by EIMSED and can be made available upon request – as full-version or country-specific extracts.

References

- Is CME primarily national? Or can it be global? WentzMiller Associates Newsletter; Dec 2010-Jan 2011. http://www.wentzmiller.org/cmenewsletters2011.html

- Educating the Market: Creating Value Through Support of Continuing Medical Education. Chapel Hill, NC USA: Best Practises LLC; June 2010. http://www.marketresearch.com/Best-Practises-LLC-v3339/ Educating-Creating-Value-Support-Continuing-2765035/

- Continuing Medical Education and Professional Development in Europe. Development and Structure. Brussels, Belgium: European Union of Medical Specialties (UEMS); Apr 2008.

- EJ Desbois, H Pardell, A Negri, . Continuing Medical Education in Europe – Evolution or Revolution? Malakoff, France: MedEd Global Solutions; 2010.

- Data on file, White Cube Health Care, 2010.