Abstract

Background: To investigate the characteristics of people with insulin-treated diabetes, who have experienced severe hypoglycaemic events (SHEs), in Germany, Spain or UK.

Methods: Patients with type 1 (n=319) or insulin-treated type 2 diabetes (n=320) who had experienced ≥1 SHE in the preceding year were enrolled. Their median age was 53 years (range, 16–94 years). Data were collected using a questionnaire administered by an experienced interviewer.

Results: The median number of reported SHEs was 2–3 in 12 months. Most events (69%) occurred at home, usually during the day or evening (74%) and most commonly due to insufficient food consumption (45%). In patients whose hypoglycaemia awareness was tested, 68% had normal awareness. Patients requiring emergency healthcare treatment frequently had impaired hypoglycaemia awareness, and developed hypoglycaemic coma more often. Hospital treatment was usually provided in an emergency department (72–94%). The duration of stay was longest in Germany. Following a SHE, patients receiving professional treatment were more likely to: consult their physician, test their blood glucose more often, adjust insulin dose and receive self-management training.

Conclusions: This survey of diabetes patients aged 16–94 years showed that SHEs represent a substantial burden on national healthcare systems in Germany, UK and Spain. The pattern of occurrence and treatment was similar in all three countries, despite differences in cultures and healthcare systems.

Introduction

Severe hypoglycaemia is a frequent complication of insulin therapy in people with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), who often experience severe hypoglycaemic events (SHE), i.e. those requiring external help for recovery. The annual prevalence of such events in people on conventional therapy is 30–40%Citation1–4, but such events are less common in people with insulin-treated type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM)Citation4–6.

The main objectives of the present study were to investigate management of SHEs in three different European countries and to explore national similarities and differences in the management of severe hypoglycaemia and resources used in the healthcare systems. This was achieved through patient interviews, using a detailed questionnaire to record the features of the hypoglycaemic event, how it was managed, what subsequent changes were made to care and management of the patient (with particular emphasis on what types of healthcare resources are employed) and how management differed between patients with T1DM and insulin-treated T2DM.

The definition of a SHE used in the survey was an event for which the patient needed external help for recovery, whether provided by family members or a healthcare professional (HCP) in the community or hospital. Three treatment groups were defined to allow the survey results to be assessed in more detail: (1) those who were treated without the help of a HCP, (2) those who received emergency aid from an HCP outside the hospital and (3) those who where treated in the hospital setting (including the emergency department and admission to medical wards).

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a retrospective survey, collecting qualitative and quantitative data on the experiences of individual patients who had experienced SHEs. Information was collected on the patients’ experience during and after their treatment, including the healthcare resources employed throughout. Patients were asked about events in the previous 12 months, as recall of SHEs over this length of time has been shown to be robustCitation7. Patient interviews were conducted using telephone and face-to-face interviews with adults (aged ≥18 years) and adolescents (aged 16 or 17 years) with insulin-treated diabetes in three European countries: UK, Germany and Spain. Only the quantitative results of the survey are presented in this paper.

Patients

Participants were recruited by HCPs (family doctors, hospital physicians and nurses). To be eligible, participants had to be aged 16 years or older, receiving insulin for either T1DM or T2DM (the latter group of patients could have been receiving an oral antidiabetic agent in addition to insulin), and have had a SHE in the previous 12 months.

Eligible patients were grouped into three categories according to how the SHE was managed and treated. Group 1 patients (‘Family/domestic’) were treated by a family member or friend, and had no contact with a HCP. Patients who received treatment from a HCP were categorised either as Group 2 (‘Community HCP’), who received emergency treatment from a paramedic or medical practitioner without requiring hospital admission, or Group 3 (‘Hospital HCP’), who required treatment in a hospital setting. The number of patients eligible for inclusion in Group 1 was expected to be much higher than for Groups 2 or 3, and so a minimum recruitment limit of 50 patients per group (type 1 and type 2 patients combined) was set for each country.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed using qualitative input from separate focus-group meetings with patients, emergency physicians and diabetes specialists in each of the three countries. A total of nine focus-group meetings were held, to gain insight into the impact of SHEs on patients and physicians, their characteristics and frequency, how they were managed at the time and how physicians expected the management of hypoglycaemia to develop in the future. The resultant questionnaire was tested in UK patients before the quantitative phase of the study began. The study questionnaire consisted of 53 questions, the main groups of which are shown in . Open and closed questions were included, and for recording the level of awareness of hypoglycaemia, the patient's answer was recorded on a Likert scale. This scale had possible scores of 1 to 7 where 1 = always aware, 7 = never aware and scores of 1–3 are considered to represent normal awareness (with 4–7 representing impaired awareness)Citation8,9. The question about hypoglycaemia awareness was added to the questionnaire after most UK interviews were completed, and only six patients in the UK were asked this question. Questionnaires were completed by the interviewer during a 25-minute interview during February and March 2007, conducted either by telephone (Spain and UK) or face-to-face (Germany). If patients had experienced more than one SHE in the previous 12 months, they were asked to describe the features and treatment of the most recent event.

Table 1. Contents of patient questionnaire.

Statistical analyses

For the main survey questionnaire, the planned sample size for each country was 200 patients, with no fewer than 50 patients in any treatment group.

Most survey data were expressed as proportions, showing comparisons by treatment group, country and diabetes type. For some measures such as frequency, statistics were generated including mean and standard deviation (SD), and median and range. Medians were preferred to means both for descriptions of datasets with small patient numbers or skewed distribution and to take a conservative approach to the effect on datasets of a small number of outliers (patients who used large amounts of healthcare resources).

Logistic regression analysis and chi-square tests were performed to assess whether treatment group was associated with patient and disease characteristics at baseline, and with questionnaire responses. Analyses were carried out using Stata/IC software (version 10.0, Statacorp LP, College Station TX, USA). Statistical tests were performed using a 5% significance level.

Results

Patients

Demographic and other characteristics of the 639 patients surveyed are shown in –. The age distribution of the patients was similar in each country, with a median age of 53 years for all patients (range, 16–94 years); the median age for T1DM patients (n=319) was 38 years (range, 16–84 years) and for T2DM patients (n=320) was 62 years (range, 19–94). Only 19 patients (3.0%) were aged <18 years. Median duration of diabetes for T1DM and T2DM patients was 16 years (range, 1–58) and 13 years (range 1–49), respectively. Mean BMI was 25 kg/m2 (SD, 4.1) in T1DM patients and 29 kg/m2 (SD, 5.6) in T2DM patients. In 442 patients who knew their HbA1c value, mean self-reported values varied from 6.8% (Germany, T1DM; n=81) to 8.0% (UK, T1DM; n=74). The Spanish cohort contained more women than men, but in Germany and the UK, the numbers of men and women were well balanced. In all, 254 patients (39.7%) were in employment at the time of the interview, and 554 (87%) were living with a partner or with others. As expected, more patients met the criteria for Group 1 than for Groups 2 or 3 in each country. Nearly all additional patients recruited over and above the group quota of 50 were included in Group 1 (family/domestic).

Table 2a. Patient demographics and characteristics by treatment group and type of diabetes in Germany. Data are mean and SD unless stated.

Table 2b. Patient demographics and characteristics by treatment group and type of diabetes in Spain. Data are mean and SD unless stated.

Table 2c. Patient demographics and characteristics by treatment group and type of diabetes in the UK. Data are mean and SD unless stated. Impaired hypoglycaemia awareness using a Likert scale was not measured in the UK sample.

Most patients (441; 69%) had suffered more than one SHE in the previous 12 months. The median number of SHEs per T1DM patient in the previous 12 months was 3 (except in Germany, where the median was 2) and for T2DM patients, the median number was 2 in all countries. In Spain and the UK, a substantial proportion reported having five or more SHEs in the 12-month period (37/101 [37%] and 40/124 [32%] T1DM patients and 25/100 [25%] and 24/100 [24%] T2DM patients, respectively), but in Germany, only 12/94 (13%) T1DM patients and 13/120 (11%) T2DM patients had ≥5 events. In all three countries, the majority of the SHEs (approximately 60%) had occurred during the 6 months before the interview. Eight patients were already receiving treatment in hospital when the SHE occurred, and were excluded from the analyses relating to hospitals, i.e. transport to hospital, department involved in treating the patient, treatment received and length of stay (discharge before or after 24 h).

Factors related to treatment group

No correlation was found between the number of SHEs in the previous year and treatment group. Treatment group was not associated with educational level, marital status or which type of medical practitioner (GP or diabetologist) was mainly responsible for the patients’ diabetes care.

Impaired hypoglycaemia awareness was associated with treatment group but the extent of this depended on the way the characteristic was defined. In reply to the survey question which asked ‘What was the reason for your major hypoglycaemic event?’, 40/639 patients (6.3%) ticked the response ‘I did not notice the symptoms/I suffer from hypo-unawareness’. Significantly more patients in Germany (27/214 [12.6%]) gave this reason than those in the UK and Spain (8/201 [4.0%] and 5/224 [2.2%], respectively). The proportion of patients who gave this reason increased with the intensity of the treatment (Group 1, 11/330 [3.3%]; Group 2, 12/159 [7.5%] and Group 3, 17/150 [11.3%]), a trend which was statistically significant (p=0.003, chi-square test).

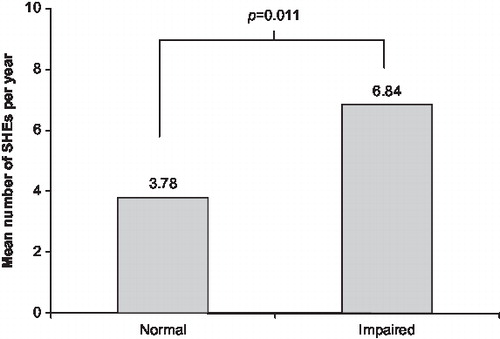

Impairment of hypoglycaemia awareness was also assessed more objectively on a Likert scale. Of the 253 patients who responded to this question (163 in Spain, 84 in Germany and 6 in the UK), 80 (31.6%) had impaired awareness (scores of 4, 5, 6, or 7 on the Likert scale). The difference between treatment groups was not significant (p=0.579). Fewer patients in Group 1 (25/88, 28%) had impaired awareness than in Group 3 (28/79, 35%). The number of SHEs experienced in the previous year by those with impaired awareness (according to the Likert scale score) was higher than those with normal awareness, a difference that was statistically significant (p=0.011; ).

Figure 1. Incidence of severe hypoglycaemic events (SHEs) in the preceding 12 months in patients with impaired hypoglycaemia awareness (n=80) and those without impaired awareness (n=173), according to Likert scale scores and categorised using the method of Gold et al Citation8 and Geddes et al Citation9.

The type of diabetes and the regular antidiabetic treatments that patients were taking at the time of the survey (insulin with or without oral antidiabetic drugs) had no apparent effect on allocation to treatment group (data not shown).

Questionnaire responses

Time of occurrence and location of the SHE.

Most SHEs (471/639; 74%) occurred during the day or evening (06:00h–22:00h); the time of occurrence was evenly distributed for T1DM patients, but not for T2DM patients; events occurring during the night (22:00h–06:00h) accounted for 100/319 (31.4%) events in T1DM patients but only 68/320 (21.3%) in T2DM patients, i.e. 252 (78.7%) events in T2DM patients occurred during waking hours. The patient's home was the location for most of the SHEs reported (439/639 [69%] events); this proportion was relatively consistent across all countries and treatment groups, in both T1DM and T2DM patients. Only 41 patients (7% of all patients) had a SHE at their workplace (equivalent to 16% of those who were in employment at the time of the SHE).

Reasons for the SHE.

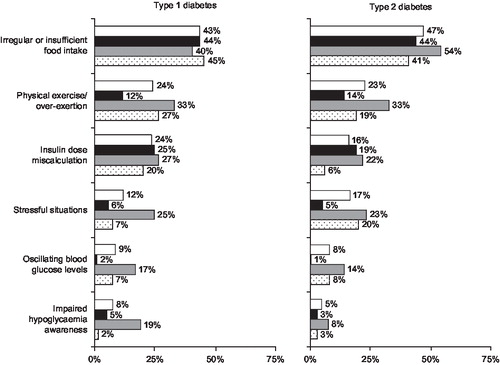

In all three countries, the main reason given for the occurrence of a SHE (reported by 288 [45.1%] of the total sample) was irregular or insufficient food intake. Other common reasons were physical exercise or exertion (148, 23.2%) and stressful situations (91, 14.2%) (patients could give more than one answer to this question). Some patients also cited unstable glycaemic control as a reason, e.g. 126 (19.7%) said that they took the wrong insulin dose (or took it at the wrong time) and 53 (8.3%) cited fluctuating blood glucose levels (). Those who said that a reason for their SHE was that they suffered from impaired hypoglycaemia awareness are described in the previous section.

Figure 2. Causes identified by patients for the severe hypoglycaemic events and number of patients (as % of group) reporting them. White bar = total of all countries (type 1, 319; type 2, 320); black bar = UK (type 1, 101; type 2, 100), grey bar = Germany (type 1, 94; type 2, 120), dotted bar = Spain (type 1, 124; type 2, 100).

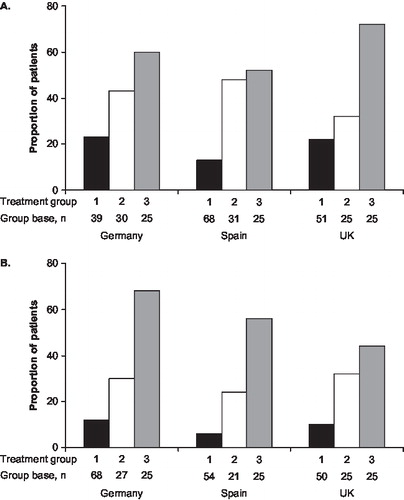

Loss of consciousness (coma) associated with the SHE was reported significantly more often by patients with T1DM (111/319, 34.8%) than with T2DM (79/320, 24.7%; p<0.01), and in all three countries, the frequency of hypoglycaemic coma was highest in Group 3 and lowest in Group 1, irrespective of diabetes type (difference not statistically significant; ). Coma was significantly associated with impaired awareness (p<0.0001), and both these variables were found to be significantly, although weakly, correlated with the duration of diabetes in logistic regression analysis (impaired awareness: r Citation2=0.01, p<0.05; coma: r Citation2=0.03; p<0.0001).

People involved in treatment of the SHE.

Group 1 patients were treated either by their partner (195/330, 59.1%), another family member (91, 27.6%) or a friend or colleague (66, 20.0%), generally with some type of refined carbohydrate (sweet drinks, 236 [71.5%]; dextrose tablets, 120 [36.4%]; sweets or chocolate, 118 [35.8%]); 23 (7%) of patients in this group reported use of glucagon by injection, and 17 (5.2%) used buccal glucose gel. The only notable difference between countries was that dextrose tablets were used more frequently in Germany than in Spain or the UK.

For Groups 2 and 3 (those receiving medical treatment from a HCP), the type of person primarily involved in the treatment differed by country. Many patients in these groups also received initial support or treatment from their partners, particularly in Germany (Group 2, 29/57 [51%]; Group 3, 23/50 [46%]), or from other family members, notably in Spain (Group 2, 18/52 [35%]; Group 3, 19/50 [38%]). In Germany and the UK, around 80% of patients were taken to hospital by ambulance (42/50 and 37/47, respectively), but far fewer (16/45, 36%) used this mode of transport in Spain, where private transport to hospital was quite common (13 [29%] patients).

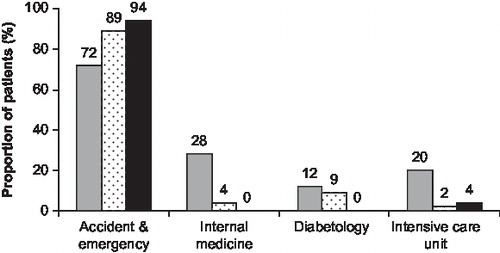

In all three countries and for both T1DM and T2DM patients, the main hospital department involved with acute treatment of the SHE was the accident and emergency (A&E) department (36/50 [72%], 40/45 [89%] and 44/47 [94%] patients in Germany, Spain and the UK, respectively; ). For Group 3 patients in Spain and the UK, this was the most common place of hospital treatment, but in Germany, the internal medicine ward and the intensive care unit were also important treatment locations, treating 14 (28%) and 10 (20%) patients, respectively, significantly more than in Spain and the UK (more than one location could be named in response to this question).

Figure 4. Hospital departments in which patients in Group 3 received initial treatment for the severe hypoglycaemic event (patients who were in hospital when the event occurred were excluded from the analysis). Key to columns: grey, Germany; dotted, Spain; black, UK.

Of those patients who were treated initially in a hospital department (31–50 in each country, excluding those already in hospital when the SHE occurred), significantly more were discharged within 24 h in Spain (27/32, 84%) and the UK (36/50, 72%) than in Germany (21/50, 42%; p<0.0001). In Germany, follow-up treatment for Group 3 patients was most often given in the internal medicine ward (22 of 28 patients), the median duration of stay being 6 days, whereas in Spain and the UK, only five and eight patients, respectively, received follow-up treatment in the hospital, with corresponding median stays in hospital of 5 and 2 days, respectively.

Change in patient behaviour after the SHE.

In all countries, most patients (T1DM and T2DM) did not make additional visits or phone calls to their main diabetes care physician after recovering from the SHE. The proportion who did increase their frequency of visits was highest in Germany (75/214, 35%); in Spain and the UK, fewer than 20% increased frequency of visits (32/224 and 36/201, respectively). The proportion who increased their frequency of phone calls was less than 20% in all three countries (Germany, 32/214; Spain, 13/224; UK, 39/201). In all countries, the median increase in the number of visits in the 3 months after the event was two, the same as the median increase in phone calls in the same period. The proportion who increased frequency of visits or phone calls was nearly always higher in Groups 2 and 3 than in Group 1 (; difference not statistically significant). The median increase in frequency of blood glucose testing was two tests per day, which usually continued for about 2 weeks and rarely for more than 4 weeks. The proportion of patients who tested glucose more frequently was highest in Group 3 (). The proportions of T1DM and T2DM patients who tested glucose more frequently were similar (data not shown). Changes to insulin dose were made by 293 (46%) of all patients surveyed and, as with blood glucose testing, the proportion of patients who made adjustments was closely associated with treatment group in all countries (). The proportion of all dosage adjustments that were sustained for a long period (judged by the patient to be ‘adjusted permanently’) was also associated with treatment group (lowest in Group 1 and highest in Group 3; data not shown). The proportion of patients who made insulin dose adjustments was slightly higher for T2DM patients than for T1DM patients (data not shown).

Table 3. Changes made by patients in self-management of diabetes after the severe hypoglycaemic event, by country and treatment category.

Many patients received additional advice and education on diabetes self-management after the SHE, and this was more frequent in patients in Group 2 (85/159, 53%) and Group 3 (80/150, 53%) than in Group 1 (111/330 [34%]; not statistically significant). Irrespective of treatment group, patients in Spain appeared to receive less advice and education than those in Germany, and those in the UK received least of all. The education was mostly in the form of dietary counselling, information leaflets and general clinical advice, and to a lesser extent, information about awareness of hypoglycaemia symptoms ().

Table 4. Training in diabetes self-management received by patients after the severe hypoglycaemic event, by country and treatment category.

A total of 157 of the 639 patients surveyed (24.6%) made other changes of behaviour after their SHE, most commonly paying more attention to the frequency and timing of meals.

Absence from work.

The number of patients who were absent from work after suffering a SHE was 18 in the UK, 25 in Spain and 32 in Germany. When expressed as a proportion of those employed, these values ranged from 22.5% in the UK to 48.5% in Germany. In all countries, the median duration of absence from work was 2 days, but the range of absence periods was wide, from a few hours to over 1 month.

Discussion

The results of the present survey show that severe hypoglycaemia remains a frequent and major side-effect of insulin treatment for diabetes in all three countries surveyed; and that successfully reducing the incidence of SHEs would not only reduce the morbidity of this problem, but would have significant benefits for healthcare by reducing demands on the emergency ambulance services and on hospital emergency wards and other departments. Hospitalisation of patients (as a consequence of diabetes or its complications) is a major component of the cost burden of diabetes in France, Spain and GermanyCitation10–12. In the present study, which was conducted in a cross-section of the diabetes patient population (ranging from 16 to 94 years of age) in Germany, Spain and UK, no demographic or clinical characteristics were identified that predicted hospitalisation (or emergency treatment) of patients who experienced SHEs, other than the presence of impaired hypoglycaemia awareness. Patients who cited impaired awareness as a reason for their SHE were significantly more common in the two groups who required professional medical treatment (Groups 2 and 3) than those treated at home (Group 1), and higher proportions of patients in Group 2 and 3 developed hypoglycaemic coma compared with those in Group 1.

Impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia is a major risk factor for severe hypoglycaemia both in T1DM and (to a lesser extent) insulin-treated T2DMCitation13, although only 6% of all patients in the present survey cited impaired hypoglycaemia awareness as a reason for their hypoglycaemic events. Hypoglycaemia is not caused by impaired awareness of symptoms – it usually results from too much insulin, inadequate consumption of carbohydrate or unexpected physical exercise – but impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia increases the risk of developing severe hypoglycaemia, by three to six times in people with T1DMCitation9,14,15. The Likert scale assessment used in this survey produced an incidence of impaired awareness of 31.6%, in better agreement with other reports. Most population surveys have reported the prevalence of impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia in insulin-treated diabetes to be around 25%Citation13, depending on how the condition is defined. A recent study using a validated method of assessment revealed a prevalence of almost 20%Citation15. In insulin-treated T2DM, the prevalence is lower at around 8–10%Citation5,16, but the risk of severe hypoglycaemia is greatly increased in those people who are affected.

In this survey, nocturnal hypoglycaemia was more common among T1DM than T2DM patients (31.4 vs. 21.3%, respectively). Longer durations of insulin treatment in T1DM patients (approximately 15–23 years in this study based on the documented duration of diabetes) may partly account for the higher incidence of nocturnal hypoglycaemia given that factors related to insulin treatment (and patient behaviour) are commonly attributed to the development of nocturnal hypoglycaemiaCitation17. Nocturnal hypoglycaemia may also be less frequent in T2DM patients because of treatment regimens that are less likely to induce nocturnal hypoglycaemia than the regimens many T1DM patients were receiving. For example, many T2DM patients would be receiving oral antidiabetic drugs in combination with a single bed-time dose of NPH insulin or a long-acting insulin analogue, which is known to confer a low risk of nocturnal hypoglycaemiaCitation18. However, with the growing tendency for introducing intensive regimens early in the management of T2DM, the potential for an increase in nocturnal hypoglycaemia events among this patient population cannot be discounted.

The pattern of changes in self-management of diabetes after a SHE was similar in all countries. About half the patients temporarily increased their frequency of glucose testing and the same proportion made adjustments to insulin dose, even though this might have raised their HbA1c and compromised their overall quality of glycaemic control. However, only a small number of patients consulted their physicians more frequently after a SHE, although those who did were more likely to have received professional treatment, and more patients in Germany made additional physician visits than patients in Spain and the UK.

Better patient education about methods of preventing hypoglycaemia and self-management of diabetes could potentially reduce the demand on medical emergency services for treating SHEs. German and Spanish patients in the current survey were much more likely to receive this training than their counterparts in the UK. Nearly 70% of all survey patients experienced more than one event in 12 months, and in Spain and the UK, 37% and 32% of T1DM patients, respectively, experienced five or more events over the same period. The high frequency of SHEs in the current survey sample was influenced by selection of patients who had experienced severe hypoglycaemia, and is not an accurate measure of annual prevalence in the community, where approximately 30–40% of people with T1DM experience one or more eventsCitation2,19,20. In patients with T1DM and insulin-treated T2DM in the UK and Germany, a history of previous hypoglycaemia has been found to be a strong predictor of future hypoglycaemic eventsCitation21,22. The current study findings emphasise the need for further studies to examine the relationship between patient training and the likelihood of repeat SHEs (for example, are patients who receive training after the first or second event less likely to experience a subsequent event than those who do not receive training), which may help to alleviate the high demand for professional assistance.

Fewer German patients experienced 5 or more SHEs (T1DM 13%; T2DM 11%) compared with patients in Spain (37% and 25%, respectively) and the UK (32% and 24%, respectively). It may be speculated that the observed differences reflect less intensive glycaemic control among German patients, which is consistent with a recently published study suggesting that T1DM and some subgroups of T2DM patients in Germany experience difficulties maintaining glycaemic targetsCitation23. However, the survey findings showed that glycaemic control (as measured by HbA1c levels) did not markedly differ across patient groups in Spain, UK and Germany. Another possible explanation for this observed difference is that education of people with diabetes at diagnosis and initiation of insulin therapy may be more widespread in Germany. Training methods pioneered in Germany to reduce the risk of SHEs without compromising the quality of glycaemic controlCitation24,25 may be more widespread in this country where the reimbursement system may favour this practice compared with the healthcare systems in the UK and Spain.

SHEs seemed to be treated more intensively by healthcare professionals in Germany. German patients were more likely than those in Spain and the UK to be treated as in-patients and to be kept in hospital longer, which was reflected in longer absences from work after a SHE in Germany. Long hospital stays were also reported in a survey of over 10,000 French patients hospitalised because of SHEs, where the average stay was 6.6 daysCitation10. Differences in SHE management may ultimately reflect differences in national healthcare systems. Unlike Spain and the UK, Germany adopts a statutory health insurance scheme for its general population that operates on the principle of reimbursement of healthcare costs, which is likely to account for more patients receiving inpatient treatment and extended stays in hospital in this survey.

Although differences between countries were observed – some of them reflecting the distinct way in which national healthcare systems work, such as the treatment of German patients on the internal medicine ward and the more widespread use of the ambulance service in the UK – it is notable that the pattern of occurrence and treatment of SHEs was broadly similar between the three countries, as were the characteristics of the patients requiring each level of treatment. These similarities persisted despite differences between healthcare systems in reimbursement and differences in the uptake of educational advice as shown in the present survey. The reason most commonly given by patients for having a SHE, namely problems with food intake, was the same in all three countries, despite the well-established cultural difference in timing of the evening meal in Spain, which is eaten much later than in Germany or the UK.

The extent to which the findings of the present cross-cultural study can be generalised or extrapolated to other European countries is constrained by the scale of the survey; the limitations of surveying small numbers of patients in each country are magnified when results are compared across treatment groups or types of diabetes. In addition, a selection bias is inevitable in such a survey because randomised screening was not used to recruit patients. This probably resulted in over-representation of patients willing to participate in survey work, and under-recruitment of patients with poor glycaemic control or with chaotic lifestyles. Although data were collected on patients’ treatment regimens at the time of the survey, no assessment was made of how appropriate these were or how this affected the frequency of SHEs or the level of treatment. Specifically, evidence suggests that oral antidiabetic drugs vary in their propensity for increasing the risk of hypoglycaemia among T2DM patientsCitation26,27, which, in this analysis, could have resulted in differences in the frequency of SHEs in this patient population.

Despite these limitations, the present survey has shown that the occurrence of severe hypoglycaemia imposes a considerable burden on healthcare systems including hospitals, emergency departments, emergency ambulance services and primary care services, not to mention the stressful experiences of relatives and friends of the patients who are required to treat SHEs or summon help. As patients with impaired hypoglycaemia awareness were more common in the groups requiring professional medical help, more training in early recognition of symptoms may help to reduce the demand on HCPs. The type of treatment given to patients in this survey showed many similarities between the countries studied, notwithstanding known health system and cultural differences. The findings from this survey of hypoglycaemia management and treatment in three European countries may be directly relevant and applicable to other European countries, and emphasise the substantial burden of managing severe hypoglycaemia.

Acknowledgements

Declaration of interests: Financial support for this study was provided by Novo Nordisk A/S (Denmark). The publication was supported by Novo Nordisk A/S (Denmark) with editorial assistance from ESP Bioscience (Sandhurst, UK).The authors are wholly responsible for the study design, analysis and scientific evaluation.

M.L. and M.H. are employees of and shareholders in Novo Nordisk. B.M.F. received a consultancy fee from Novo Nordisk for his advice during the design phase of the study, but received no financial reward for his subsequent participation as a co-investigator. He has served previously as a member of advisory boards for Novo Nordisk.

References

- Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. Hypoglycemia in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes 1997;46:271-86.

- MacLeod KM, Hepburn DA, Frier BM. Frequency and morbidity of severe hypoglycaemia in insulin-treated diabetic patients. Diabet Med 1993;10:238-45.

- Stephenson J, Fuller JH, For EURODIAB IDDM Complications Study Group. Microvascular and acute complications in IDDM patients: the EURODIAB IDDM Complications Study. Diabetologia 1994;37:278-85.

- UK Hypoglycaemia Study Group. Risk of hypoglycaemia in Types 1 and 2 diabetes: effects of treatment modalities and their duration. Diabetologia 2007;50:1140-7.

- Henderson JN, Allen KV, Deary IJ, Hypoglycaemia in insulin-treated Type 2 diabetes: frequency, symptoms and impaired awareness. Diabet Med 2003;20:1016-21.

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998;352:837-53.

- Pedersen-Bjergaard U, Pramming S, Thorsteinsson B. Recall of severe hypoglycaemia and self-estimated state of awareness in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2003;19:232-40.

- Gold AE, MacLeod KM, Frier BM. Frequency of severe hypoglycemia in patients with type I diabetes with impaired awareness of hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 1994;17:697-703.

- Geddes J, Wright RJ, Zammitt NN, An evaluation of methods of assessing impaired awareness of hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2007;30:1868-70.

- Allicar MP, Mégas F, Houzard S, Frequency and costs of hospital stays for hypoglycemia in France in 1995 [in French]. Presse Med 2000;29:657-61.

- Hart WM, Espinosa C, Rovira J. Costs of known diabetes mellitus in Spain [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc) 1997;109:289-93.

- Köster I, von Ferber L, Ihle P, The cost burden of diabetes mellitus: the evidence from Germany – the CoDiM study. Diabetologia 2006;49:1498-504.

- Frier BM. Impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia. Hypoglycaemia in Clinical Diabetes, 2nd edn. Chichester: John Wiley, 2007;141-70.

- Clarke WL, Cox DJ, Gonder-Frederick LA, Reduced awareness of hypoglycemia in adults with IDDM. A prospective study of hypoglycemic frequency and associated symptoms. Diabetes Care 1995;18:517-22.

- Geddes J, Schopman J, Zammitt NN, Prevalence of impaired awareness of hypoglycaemia in adults with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med 2008;25:501-4.

- Schopman J, Geddes J, Frier BM. Awareness of hypoglycaemia in patients with insulin-treated diabetes. Diabet Med 2008;25(Suppl 1): 97 [abstract].

- Brunton SA Nocturnal hypoglycemia: answering the challenge with long-acting insulin analogs. MedGenMed 2007;9:38.

- Allen KV, McAulay V, Sommerfield AJ, Hypoglycaemia is uncommon with a combination of antidiabetic drugs and bedtime NPH insulin for type 2 diabetes. Pract Diabetes Int 2004;21: 179-82.

- Strachan MWJ. Frequency, causes and risk factors for hypoglycaemia in type 1 diabetes. Hypoglycaemia in Clinical Diabetes, 2nd edn. Chichester: John Wiley, 2007;49-81.

- Pedersen-Bjergaard U, Pramming S, Heller SR, Severe hypoglycaemia in 1076 patients with Type 1 diabetes: influence of risk markers and selection. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2004;20: 479-86.

- Donnelly LA, Morris AD, Frier BM, Frequency and predictors of hypoglycaemia in Type 1 and insulin-treated Type 2 diabetes: a population-based study. Diabet Med 2005;22:749-55.

- Mühlhauser I, Overmann H, Bender R, Risk factors of severe hypoglycaemia in adult patients with Type I diabetes – a prospective population based study. Diabetologia 1998;41: 1274-82.

- Huppertz E, Pieper L, Klotsche J, Diabetes mellitus in German primary care: quality of glycaemic control and subpopulations not well controlled - results of the DETECT study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2009;117:6-14.

- Mülhauser I, Bruckner I, Berger M, et al Evaluation of an intensified insulin treatment and teaching programme as routine management of Type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes. The Bucharest-Dusseldorf Study. Diabetologia 1987;30:681-90.

- Jörgens V, Grüsser M, Bott U, Effective and safe translation of intensified insulin therapy to general internal medicine departments. Diabetologia 1993;36:99-105.

- Holstein A, Egberts EH. Risk of hypoglycaemia with oral antidiabetic agents in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2003;111:405-14.

- Vlckova V, Cornelius V, Kasliwal R, Hypoglycaemia with oral antidiabetic drugs: results from prescription-event monitoring cohorts of rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, nateglinide and repaglinide. Drug Saf 2009;32:409-18