Abstract

Objective: To examine adherence in clinical practice to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guideline recommendations of observing a 5-day waiting period after clopidogrel administration before undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery and to examine the costs of waiting.

Methods: This retrospective study used a nationwide inpatient database (Solucient ACTracker) to identify patients who were admitted for acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and who had same-stay CABG. Cost of additional days of stay was estimated using regression analysis.

Results: The recommended 5-day waiting was adhered to in 16.9% (n=3,809) of patients. The percentage of patients with ACS undergoing CABG surgery on day 0 was 14.6%. Adherence to the waiting was higher for teaching and rural hospitals; and in female and elderly patients and urgent admissions.

Conclusions: The recommended 5-day waiting for CABG surgery after clopidogrel treatment is poorly adhered to in clinical practice. This study was unable to determine specific reasons for the low adherence; however, there may be a compromise between the clinically urgent need for revascularisation and increased risk of bleeding, as well as economic costs associated with waiting. The cost of an additional hospital day in this group of patients was approximately £1,400 per day or £7,000 for 5 days. Thus, a full 5-day wait would have a significant economic impact on hospital costs.

Introduction

Atherosclerotic plaque rupture and subsequent thrombus formation is the primary aetiology of acute coronary syndrome (ACS). Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with stent placement is widely used and is effective for patients with ACS, but this procedure contributes to plaque disruption, platelet activation and subsequent aggregation. Platelet accumulation and acute stent thrombosis can also occur shortly after stent implantation. Because of the integral role of platelets in the process of thrombus formation, early and aggressive antiplatelet therapy is needed.

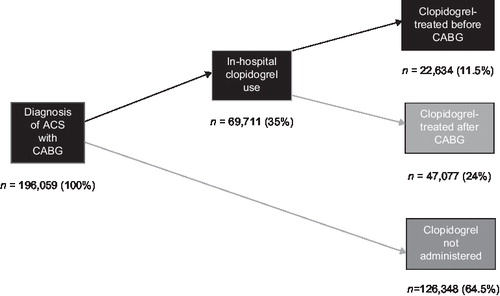

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines for patients with unstable angina (UA) or non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) recommend oral clopidogrel administration (either 300 mg or 600 mg), in addition to aspirin, prior to angiography in patients who are expected to undergo coronary revascularisationCitation1–3. While a majority of patients undergo PCI after diagnostic catheterisation, 10–20% of patients in the US undergo coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery during the index hospitalisation ()Citation4–10. Recent data from the Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable Angina Patients Suppress ADverse Outcomes with Early Implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines (CRUSADE) registry also highlight the difficulty of predicting which patients will need to undergo CABG surgeryCitation11. Because clopidogrel demonstrates irreversible platelet effects, the ACC/AHA and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) recommend discontinuing clopidogrel administration 5–7 days before elective CABG surgery in order to allow for platelet recoveryCitation1,2,12.

Table 1. Rates of CABG surgery during hospitalisation from major clinical trials.

Some institutions withhold initial clopidogrel administration if patients are sent for cardiac catheterisation within 24 h of admission, but data suggest that clopidogrel should be administered up to 15 h before PCI in order to obtain optimal patient benefitCitation13. This creates a clinical challenge because the need for CABG surgery cannot be predicted early in a patient's course of care but a delay in CABG surgery can incur additional hospital days and unrecognised hospital costs. According to fourth-quarter data from 2006, approximately 60% of patients without any contraindication to treatment received clopidogrel within the first 24 h of hospital admissionCitation10. Thus, the likelihood of encountering patients who receive clopidogrel prior to CABG surgery is fairly high.

Previous research has identified non-adherence to the recommended 5-day waiting period. Mehta and colleagues found that 87% of patients treated with clopidogrel underwent CABG surgery within 5 days of clopidogrel administration based on 852 NSTEMI patients in the CRUSADE dataCitation11. Since CRUSADE registry's goal was to improve adherence and quality of care, the findings generalisability to the usual care setting is unclear.

Mehta and colleagues also identified that patients who underwent CABG surgery within 5 days experienced a significant increase in blood transfusions and a need for at least 4 or more units of transfused blood compared to patients who did not undergo CABG surgery within 5 days of clopidogrel administrationCitation11. A number of published studies have also found increased blood loss, increased transfusion requirement, more frequent surgical repair of bleeding sites, prolonged length of stay, and prolonged intubation periods in patients who received clopidogrel prior to CABG surgeryCitation14–20.

The objectives of this study were to examine adherence in usual clinical practice to the ACC/AHA guideline recommendation of a 5-day waiting period after clopidogrel administration before patients undergo CABG surgery using a nationally representative database, and to discuss potential costs of empiric clopidogrel pretreatment in patients who require same-stay CABG surgery.

Patients and methods

Adherence

An inpatient database (Solucient ACTracker, Solucient Inc., Evanston, IL, USA) was used. The Solucient ACTracker is a de-identified database that provides comprehensive information on inpatient drug use, diagnoses, procedures, provider specialties, and lab test results. The Solucient ACTracker database consists of a nationally representative sample of hospitals with over 542 hospitals and over 13.7 million patients, and tracks all clinical information (such as drugs, diagnoses, procedures, length of stay, physician specialty, and patient and hospital characteristics) of the participating hospitals. The database is representative of the short-term, non-federal general hospitals in the US.

This retrospective study obtained data from January 1, 2003 to March 31, 2006, and included 196,059 patient admissions with a qualifying diagnosis of ACS plus same-stay CABG procedure from 294 hospitals with a cardiac centre. ACS was defined by a diagnosis of UA, NSTEMI, or ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Corresponding diagnosis codes used for ACS were 410–410.9 or 411.1 (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM]). CABG procedures were identified using procedure codes of 33,510–33,516 and 33,533–33,536 (Current Procedural Terminology, 4th Edition [CPT-4]). Clopidogrel was identified by the National Drug Code (NDC) from National Drug Data File (NDDF) Plus, First DataBank, Inc ().

Table 2. Clopidogrel national drug codes.

Results

Adherence

Of the nearly 200,000 cases eligible for the study, 69,711 patients (35.5%) were treated with clopidogrel during their hospitalisation. Of this subgroup, 22,634 patients (32.4% of clopidogrel-treated patients, or 11.5% of the total) received clopidogrel before CABG surgery ().

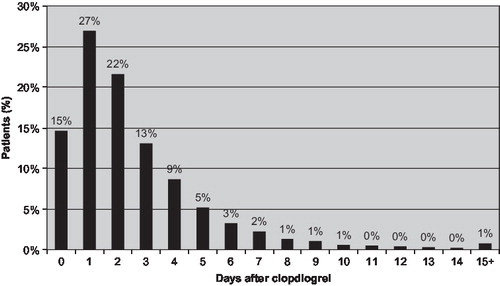

The recommended 5-day waiting period was adhered to in 16.9% (n=3,809) of patients who received clopidogrel before CABG surgery. As shown in , 14.6% of patients underwent CABG surgery the same day, and most patients underwent CABG surgery within several days of clopidogrel administration.

shows the percentage of patients who met the recommended 5-day waiting period. Adherence to the waiting period differed according to hospitals’ teaching status, urban/rural location, geographic region, and hospital size (as number of beds). Adherence rate also differed according to patients characteristics, such as sex, age, admission type, and comorbidities; also by insurance type. Adherence was higher for teaching and rural hospitals. There was a significant difference by geographic regions, where the North Central showing the lowest adherence (12.46%) while the West had the highest adherence (22.64%). Hospitals with 500 or more beds had an 18.91% adherence rate, while hospitals with fewer than 200 beds had a 13.74% adherence rate. Adherence also varied by patient type; female (18.71%) versus male (15.98%) and elderly (18.18%) versus non-elderly patients (15.39%), and urgent admissions (29.94%) versus non-urgent (8.39%), were more likely to wait 5 days before undergoing CABG surgery.

Table 3. Waiting adherence.

Discussion

The results of this retrospective study showed that the suggested 5-day waiting period for CABG surgery after clopidogrel administration is poorly adhered to in clinical practice. After clopidogrel treatment, approximately only 1 out of 6 patients waited the recommended 5 days before undergoing CABG surgery. In addition, the percentage of patients meeting the waiting period varied between subgroups categorised by hospital type, hospital size and patient type. This waiting pattern suggests a mitigated adherence pattern due to a clinical need to urgently revascularise patients who faced an increased risk of bleeding, as well as possible resource considerations. Studies examining cost of hospital days among CABG patients reported an additional day of stay cost from $1,996 to $2,307 in the USCitation20–22. Thus, adherence to the waiting period would incur approximately $10,000 (£7,000) or more for the full 5 days.

The use of clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI is strongly recommended in clinical guidelinesCitation1–3. The clinical evidence to support these high-level recommendations come from the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events (CURE) and Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) trialsCitation6,24. In the CURE trial, patients who received a combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin experienced a significant 20% relative risk reduction (RRR) in the occurrence of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction (MI), or stroke at 30 days and at 1 year compared to patients who received aspirin alone (p<0.001)Citation6. Patients who underwent PCI in the CURE trial and received clopidogrel plus aspirin demonstrated a significant 30% RRR in the composite endpoint compared to patients who received aspirin alone (p=0.03)Citation25. In the CREDO trial, in which all patients underwent PCI with stent placement, patients who received clopidogrel plus aspirin demonstrated a significant RRR of 27% at 1 year for cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke compared to patients who received aspirin alone (p=0.02)Citation24.

The CREDO trial investigators also analysed the effect of clopidogrel administration prior to PCI in order to examine whether the time of administration impacted clinical outcome. Patients received a 300-mg loading dose of clopidogrel between 3 h and 24 h before PCI (mean: 9.8 h)Citation24. A total of 51% of patients received their loading dose 3 h to <6 h before PCI, and the remaining 49% received their loading dose 6–24 h before PCI. Among patients who received their 300-mg loading dose in close proximity to PCI (within 6 h), no benefit of clopidogrel pretreatment was found. However, patients who received their 300-mg loading dose of clopidogrel at least 6 h or more before PCI experienced a 38.6% RRR at 28 days for the combined endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI, and urgent target vessel revascularisation (95% confidence interval [CI], –1.6–62.9; p=0.051). These data have increased the interest in time to onset of clopidogrel as a potentially important clinical issue. Use of high loading doses, such as 600 mg, has become more popular as a way to overcome this problemCitation26. However, the benefits of high loading doses of clopidogrel remain to be demonstrated in a large randomised trial.

Clinical trial data suggest that the rate of CABG surgery during a hospitalisation for ACS may exceed the ischemic event rate averted by clopidogrel. For example, in the CURE trial, the combined endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke occurred in 2.1–2.5% of patients during the first 7 days in the clopidogrel and control treatment groups, respectively, while the occurrence of same-stay CABG surgery was 8.1%Citation27. As shown in , the incidence of same-stay CABG surgery ranges from 7.8–18.6% in a number of published studies. Therefore, the frequency of CABG surgery must be balanced in context with the use of clopidogrel to reduce cardiac ischemic events.

This finding does not address several important factors that influence the practice pattern. In order to better understand the practice pattern, this finding points to the need for further research in several areas. The first point is the clinician's preference in timing to revascularise the patient with a CABG surgery. The present study is unable to quantitatively measure the clinical urgency of the patients’ needs for revascularisation before the recommended 5-day wait. Additionally, it is possible that there are different preferences according to specialty. For example, surgeons may need to address the risk of bleeding in situations where there are no alternatives to blood products, whereas cardiologists may need to address the risk of ischemic events. The second point to consider is costs and efficiencies in the hospitals and how they are actually influencing practice pattern. For example, it is little understood how a longer hospital stay adversely impacts the ability to care for additional patients. Additionally, our study did not attempt to account for costs of clopidogrel-prevented ischemic events or costs of CABG surgery-related bleeding after clopidogrel administration. It would be a productive effort to broaden the scope of analyses to account for full economic costs of the wait decision. Also, validation of our results using data from a specific hospital or hospital group is also warranted.

Conclusion

The ACC/AHA-recommended 5-day waiting period for CABG surgery following clopidogrel treatment is poorly adhered to in clinical practice. After clopidogrel treatment, only one out of six patients underwent CABG surgery after the suggested 5-day waiting period. The cost of an additional day of stay in discharged patients who underwent CABG treatment was estimated to be approximately $2,000 (£1,400). Thus, a full 5-day wait in the hospital for delayed CABG would incur a direct cost of approximately $10,000 (£7,000) per eligible patient in the US. More research is needed to better understand this pervasive risk-benefit trade-off in patient care.

Transparency

Declaration of funding: Eli Lilly & Co. and Daiichi-Sankyo Inc. funded this study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships: J.B. and P.M. have disclosed that they are full time employees of Eli Lilly.

Acknowledgment:

The authors thank Rebekah Conway at i3 Statprobe for editorial assistance.

Notes

References

- Braunwald E, Antman EM, Beasley JW, ACC/AHA guideline update for the management of patients with unstable angina and non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction – 2002: summary article: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina). Circulation 2002;106:1893–1900.

- Anderson JL, Adams CD, Antman EM, ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction) developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:e1–157.

- Smith SC Jr, Feldman TE, Hirshfeld JW Jr, ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 Guideline Update for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention(Summary Article: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:216–235.

- Petersen LA, Normand SL, Leape LL, Regionalization and the underuse of angiography in the Veterans Affairs Health Care System as compared with a fee-for-service system. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2209–2217.

- Cannon CP, Weintraub WS, Demopoulos LA, Comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in patients with unstable coronary syndromes treated with the glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1879–1887.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2001;345:494–502.

- Mandelzweig L, Battler A, Boyko V, The second Euro Heart Survey on acute coronary syndromes: characteristics, treatment, and outcome of patients with ACS in Europe and the Mediterranean Basin in 2004. Eur Heart J 2006;27:2285–2293.

- Grzybowski M, Clements EA, Parsons L, Mortality benefit of immediate revascularization of acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in patients with contraindications to thrombolytic therapy: a propensity analysis. JAMA 2003;290:1891–1898.

- Ferguson JJ, Califf RM, Antman EM, SYNERGY Trial Investigators. Enoxaparin vs unfractionated heparin in high-risk patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes managed with an intended early invasive strategy: primary results of the SYNERGY randomiczed trial. JAMA 2004;292:45–54.

- CRUSADE Quarter 4, 2006 Results. Available at: www.crusadeqi.com/Main/SlideSets.shtml [Last accessed: 10 January 2008].

- Mehta RH, Roe MT, Mulgund J, Acute clopidogrel use and outcomes in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;48:281–286.

- Ferraris VA, Ferraris SP, Moliterno DJ, Society of Thoracic Surgeons. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons practice guideline series: aspirin and other antiplatelet agents during operative coronary revascularization (executive summary). Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:1454–1461.

- Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Brennan DM, CREDO Investigators. Optimal timing for the initiation of pre-treatment with 300 mg clopidogrel before percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:939–943.

- Chu MW, Wilson SR, Novick RJ, Does clopidogrel increase blood loss following coronary artery bypass surgery? Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78:1536–1541.

- Leong JY, Baker RA, Shah PJ, Clopidogrel and bleeding after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;80: 928–933.

- Ascione R, Ghosh A, Rogers CA, In-hospital patients exposed to clopidogrel before coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a word of caution. Ann Thorac Surg 2005;79:1210–1216.

- Kapetanakis EI, Medlam DA, Boyce SW, Clopidogrel administration prior to coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: the cardiologist's panacea or the surgeon's headache? Eur Heart J 2005;26:576–583.

- Englberger L, Faeh B, Berdat PA, Impact of clopidogrel in coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2004;26:96–101.

- Chen L, Bracey AW, Radovancevic R, Clopidogrel and bleeding in patients undergoing elective coronary artery bypass grafting. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2004;128:425–431.

- Bae J, Powell-threets K, McCollam P. Adherence to the waiting period recommendation in acute coronary syndrome patients who undergo same-stay coronary bypass graft surgery. Circulation 2007:115:21:18–19.

- Weintraub WS, Mahoney EM, Lamy A, Long-term cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel given for up to one year in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:838–845.

- Candrilli S, Mauskopf J. How much does a hospital day cost? Value Health 2006:9:3:A56.

- Kang W, Theman TE, Reed JF3rd, The effect of preoperative clopidogrel on bleeding after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Surg Educ 2007;64:88–92.

- Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT3rd, Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288: 2411–2420.

- Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events trial (CURE) Investigators. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet 2001;358: 527–533.

- Wang C, Kereiakes DJ, Bae JP, Clopidogrel loading doses and outcomes of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes. J Invasive Cardiol 2007;19:431–436.

- Yusuf S, Mehta SR, Zhao F, Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators. Early and late effects of clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation 2003;107:966–972