Abstract

Objective:

To compare characteristics, healthcare resource utilization and costs of Medicaid bipolar disorder (BPD) type I (BP-I) patients with and without frequent psychiatric intervention (FPI).

Methods:

Adults with BP-I, ≥1 prescription claim for a mood stabilizer/atypical antipsychotic and 24 months’ continuous medical/prescription coverage were identified (MarketScan Medicaid database). Patients with ≥2 clinically significant events (CSEs) during a 12-month identification period had FPI. CSEs included emergency department (ED) visits or hospitalizations with a principal diagnosis of BPD, addition of a new medication to the first observed treatment regimen or ≥50% increase in BPD medication dose. Demographic and clinical characteristics were evaluated for the identification period, and healthcare utilization and costs for the 12-month follow-up. Multivariate generalized linear modeling and multivariate logistic regression, respectively, were used to evaluate the impact of FPI on all-cause and psychiatric-related costs and risk of psychiatric-related hospitalization and ED visit during follow-up.

Results:

Of 5,527 BP-I patients, 53% had FPI. Relative to patients without FPI, those with FPI were younger and more likely to be female, had higher adjusted all-cause (+US$3,232, p < 0.001) and psychiatric-related (+US$2,519, p < 0.001) costs and higher risk of hospitalization (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 3.681, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 2.85–4.75) and ED visit (OR = 3.094, 95% CI = 2.55–3.76).

Limitations:

Analysis used a convenience sample of Medicaid enrollees in several geographically dispersed states, limiting generalizability. Analyses of administrative claims data depend on accurate diagnoses and data entry.

Conclusion:

BP-I patients with FPI incurred significantly higher healthcare resource utilization and costs during the follow-up period than those without FPI.

Introduction

Bipolar disorder (BPD), a recurrent mood disorder characterized by dramatic shifts in mood and energy level, is associated with significant impairments in social and occupational functioning and increased risk of substance abuse and suicideCitation1–4. BPD type I (BP-I) is distinguished by the presence of manic or mixed episodes as opposed to less severe hypomanic episodesCitation5. Merikangas et al. (2007) estimated the lifetime prevalence of BP-I at 1.0% of the United States (US) populationCitation6. They found that the prevalence was higher among women (1.1%) than among men (0.8%) and that the average age of onset was 18.2 years, with most patients experiencing their first episodes between their late teens and early fortiesCitation6.

Bipolar disorder is a costly condition. In a study of the cost of BPD to employers in 2001–2002, regression-adjusted annual costs for medical services were US$5,492 among employees with BPD versus US$1,632 among other employees (p < 0.05)Citation7. Regression-adjusted annual costs for prescription medications were US$2,496 among employees with BPD versus US$630 among other employees (p < 0.05)Citation7. A large study of patients with BPD (n = 67,862) in a managed-care claims database found annual treatment charges of US$12,797 and annual reimbursement of US$6,581, in 2002 dollarsCitation8. A study of 6,072 patients with BPD and 60,643 patients with unipolar depression in an administrative claims database found that mean annual direct costs associated with BPD were US$10,402, in 2004 dollarsCitation9. Costs associated with BPD were significantly higher than those associated with unipolar depression (US$7,494, p < 0.001)Citation9.

Studies of the cost burden of BPD have generally compared direct or indirect costs of patients with BPD to those of patients without BPD. Such studies provide valuable context but do not help to describe variation in healthcare service utilization and costs among patients with BPD. Research into this matter may suggest ways to minimize the economic burden of the condition and assist in health policy decisions. Studies comparing costs among patients with BPD are rare. Brook et al. (2007) examined the change in direct healthcare costs of employees and dependents with BPD after treatment initiationCitation10. For most patients, medical costs decreased, while prescription costs increased. Among patients who initiated atypical antipsychotic treatment, the adjusted incremental increase in prescription costs of US$656 was offset by the adjusted incremental decrease in total medical costs of US$2,886Citation10.

Haskins et al. (2010) examined differences between patients requiring different levels of psychiatric intervention, analyzing electronic medical records for 632 patients with BPD treated at Duke University Medical Center from 1995 to 2005Citation11. The authors defined frequent psychiatric intervention (FPI) as four or more clinically significant events (CSEs) requiring intervention in a 12-month period. CSEs included any psychiatric hospitalization, any emergency department visit related to BPD and any change in psychotropic medication associated with psychiatric symptoms. The study found that patients with FPI had higher mean emergency department visits per patient (2.2 vs. 0.5, p < 0.0001) and more mean inpatient days per patient (5.5 vs. 1.7, p < 0.0001). Direct psychiatric costs per patient were $11,414 for patients with FPI and $4,790 for patients without FPI; no inferential statistics were reported for costsCitation11.

The present study extends the research into healthcare service utilization and costs among patients with BPD requiring different levels of psychiatric intervention. The purpose of this study was to compare patients with BP-I who experienced at least two psychiatric interventions over a 12-month identification period (year 1) with patients who did not, in terms of (all-cause) healthcare costs, psychiatric-related costs, psychiatric hospitalization and psychiatric emergency department utilization during the subsequent 12 months (year 2).

Methods

Data sources

Data from the Thomson Reuters MarketScan Multi-State Medicaid Database for calendar years 2004 through 2006 were used to conduct this retrospective study. The database consists of de-identified medical and outpatient prescription drug claims from individuals insured by Medicaid programs in several geographically dispersed states. The database contains pooled claims data on over 22 million enrollees and includes inpatient and outpatient services, outpatient prescriptions, enrollment and long-term care claims.

Study cohorts

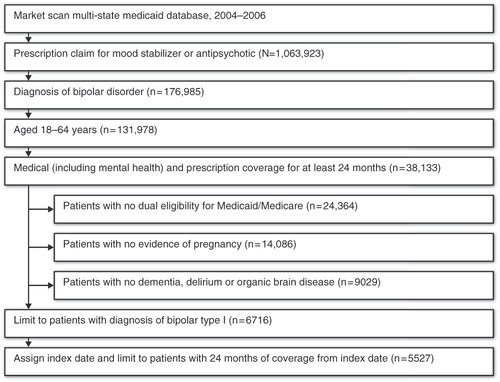

Initially identified for analysis were adults aged 18–64 years (inclusive) having at least one outpatient or inpatient medical claim with a diagnosis of BP-I (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification [ICD-9-CM] codes 296.0, 296.4–296.7); one prescription claim for a mood stabilizer (e.g., lithium or an anticonvulsant) or an atypical antipsychotic (see Appendix for list of drugs); and continuous medical and prescription Medicaid coverage (including mental health benefits) for at least 24 months. Patients with evidence of pregnancy or childbirth, dementia, delirium or organic brain disorders and patients who were dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare during the 24-month period were omitted from analysis (since prescription data were not available for these patients after December 31, 2005). The patient selection process is illustrated in .

Patients were identified as having FPI if they had two or more CSEs, separated by at least 14 days, during a 12-month period (year 1). CSEs were defined as (1) emergency department visits with a principal diagnosis of BPD (any subtype), (2) inpatient hospital admissions with a principal diagnosis of BPD (any subtype), (3) a prescription claim for a BPD medication (lithium, an anticonvulsant [first- or second-generation], an antipsychotic [typical or atypical] or an antidepressant) that was not part of the first observed treatment regimen or (4) a 50% or greater increase in the dose of the first observed medication for the treatment of BPD. If more than one CSE occurred within a 14-day window, the first event was captured. For patients with a CSE occurring at least 12 months before the end of their enrollment, year 1 began on the date of the first CSE. For other patients, year 1 began on the date of the first observed BPD diagnosis (i.e., the diagnosis that qualified patients for enrollment in the study). Finally, patients were required to have continuous medical and prescription Medicaid coverage throughout year 1 and the subsequent 12-month period during which outcomes were evaluated (year 2).

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Patient demographic characteristics included age at the start of year 1, gender, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, black and other), state or payer (ten geographically dispersed states), population density (urban vs. rural residence) and insurance plan type (those with capitated payment arrangements vs. those without). The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score, which estimates the burden of co-morbid illness from diagnoses associated with chronic diseases listed on healthcare claimsCitation12,Citation13, was calculated during year 1. Higher CCI scores indicate a greater probability of death or major disability due to co-morbid illness, and the CCI has been used as a measure of health status in prior studies of patients with BPDCitation8–10,Citation14. Additionally, a series of flags was created to indicate the presence of depression, substance abuse, anxiety disorder, diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia diagnoses during year 1. Flags were also created to indicate prescription claims for various classes of psychiatric medications used to treat BPD (lithium, anticonvulsants/mood stabilizers, conventional antipsychotics, atypical antipsychotics and antidepressants) during year 1. The primary independent variable of interest was FPI status, determined by the number of CSEs occurring during year 1. Finally, patients with FPI in year 1 who had at least two CSEs in year 2 (i.e., FPI in year 2) were also flagged.

Healthcare resource utilization and direct medical costs

All-cause and psychiatric-related healthcare resource utilization and associated direct medical costs were summarized during year 2 for the following categories of service: hospital admissions, emergency department visits, outpatient visits and outpatient prescriptions. Psychiatric hospital admissions were defined as those carrying a psychiatric diagnosis (ICD-9-CM codes 290.xx–314.xx) as the principal diagnosis on the claim. Psychiatric emergency department and outpatient visits were defined as those carrying a psychiatric diagnosis (ICD-9-CM codes 290.xx–314.xx) as the primary or secondary diagnosis on the claim. Psychiatric-related outpatient prescriptions included those for all psychotropic medications. Costs in all categories of service were calculated as the actual amounts paid to the provider by Medicaid and by patients (i.e., deductibles and co-payments). Pharmaceutical costs represent the sum of the drug's ingredient cost, administrative dispensing fee and sales tax and include both deductibles and co-payments. All-cause costs represent the sum of the costs of all medical and prescription claims paid to the provider; total psychiatric-related costs represent the sum of the costs of psychiatric-related medical and prescription claims paid to the provider. Mean costs were reported and were converted to 2007 US dollars using the medical component of the consumer price index.

Analysis

Frequency distributions, means and standard deviations were calculated for all variables other than state. Distribution by state could not be reported because of confidentiality agreements with data contributors. No missing values were found. The descriptive analyses were stratified by FPI status (patients with at least two CSEs vs. those with fewer than two CSEs during year 1). Bivariate statistical testing (chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables) was used to evaluate differences between the two groups. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The associations between FPI status in year 1 and all-cause and psychiatric-related costs in year 2 were assessed by means of general linear modeling. Additionally, logistic regression models were used to assess the impact of FPI on the risk of a psychiatric hospitalization or emergency department visit during year 2. All multivariate models were adjusted for age, gender, race, residence in a metropolitan statistical area, state, health plan type (capitated health plan or other), CCI score, co-morbid depression, substance abuse, anxiety disorder, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, first observed medication class and FPI status. Although results for the state indicator variables could not be reported, the variables were included to control for geographical variation. Significance levels were not adjusted to account for multiple outcome measures (multiplicity).

Results

Patient characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the study cohort are presented in . A total of 5,527 patients were identified for analysis. Approximately 71.3% (n = 3,939) were female and 41.5% (n = 2,295) were aged 18–34 years. The average age (standard deviation [SD]) of the study cohort was 37.7 years (10.7). More than three-quarters (n = 4,391 [79.4%]) of the study cohort were non-Hispanic white; 66.6% (n = 3,680) resided in an urban area; 54.2% (n = 2,997) had health insurance coverage by a plan with capitated payment arrangements. There were 2,932 patients flagged as having FPI (53.0%), and tests of differences in patient demographic characteristics indicated several significant differences between patients with and without FPI. On average, patients with FPI were younger (37.0 vs. 38.5 years), more likely to be female (74.8 vs. 67.3%), more likely to be non-Hispanic white (81.7 vs. 76.9%) and more likely to have health insurance coverage by a plan with capitated payment arrangements (57.1 vs. 51.0%) than those without FPI (p < 0.001 for all).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of BP-I patients with and without FPI, year 1.

During year 1, approximately three-quarters of patients (75.9%) had a prescription claim for an atypical antipsychotic; the majority (64.6%) had a claim for an anticonvulsant; and 20.5% had a prescription claim for lithium (). More than three-quarters of patients (76.6%) had a prescription claim for an antidepressant during year 1. The average (SD) CCI score of the sample was 0.53 (1.02). Approximately one-third of patients (33.7%) had a diagnosis of depression, 22.3% had a diagnosis of anxiety and 15.4% had a diagnosis of substance abuse.

Table 2. Clinical characteristics of BP-I patients with and without FPI, year 1.

Several significant differences were discovered in the clinical characteristics of patients with FPI and those without FPI during year 1. Relative to patients without FPI, those with FPI were more likely to have a prescription claim for a medication within each of the classes of psychiatric medications considered, including lithium, anticonvulsants/mood stabilizers, conventional and atypical antipsychotics and antidepressants (p < 0.001 for all). Additionally, patients with FPI had a higher rate of depression, anxiety, substance abuse, hypertension and dyslipidemia compared with those without FPI. Among those flagged as having FPI in year 1, 28.6% also had FPI in year 2, while 5.8% of patients without FPI in year 1 had FPI in year 2 (p < 0.001 for both).

Adjusted cost estimates

presents the multivariate-adjusted mean estimates of all-cause and psychiatric-related costs incurred during year 2 for patients with and without FPI. As shown in , total adjusted all-cause costs were US$11,376 for patients with FPI and US$8,144 for patients without FPI; the marginal cost associated with FPI was US$3,232 (standard error [SE] = US$407; p < 0.001). Factors associated with higher total costs included being male; having a higher CCI score; having hypertension or dyslipidemia; and receiving lithium, conventional antipsychotics or antidepressants (p < 0.05 for all). Adjusted psychiatric-related costs were US$6,014 for patients with FPI and US$3,495 for those without FPI; the marginal psychiatric-related cost associated with FPI was US$2,519 (SE = US$177; p < 0.001). Factors associated with higher psychiatric-related cost included older age; being male; residing in an urban area; and receiving lithium, anticonvulsants/mood stabilizers, conventional antipsychotics or antidepressants (p < 0.05 for all).

Table 3. Multivariate-adjusted mean costs (2007 US$) of BP-I patients with and without FPI, year 2.

In , the odds of a psychiatric hospitalization during year 2 for patients with FPI was 3.681 times the odds for patients without FPI (p < 0.01). With all other covariates held at their means, the predicted probability of psychiatric hospitalization was 11.1% among patients with FPI and 3.3% among those without FPI, a difference of 7.8 percentage points (p < 0.01). Factors associated with a higher probability of psychiatric hospitalization included capitated health plan arrangements and the presence of depression, substance abuse, anxiety disorder, diabetes or dyslipidemia (p < 0.05 for all).

Table 4. Multivariate-adjusted utilization probabilities of BP-I patients with and without FPI, year 2.

Also in , the odds of a psychiatric emergency department visit for patients with FPI was 3.094 times that for patients without FPI (p < 0.01). With all other covariates held at their means, the predicted probability of a psychiatric ER visit was 16.4% among patients with FPI and 5.9% among patients without FPI, a difference of 10.5 percentage points (p < 0.01). Factors associated with a higher probability of a psychiatric ER visit included younger age; being female; higher CCI score; and the presence of substance abuse, anxiety disorder or dyslipidemia (p < 0.05 for all). The use of lithium, conventional antipsychotics, atypical antipsychotics or antidepressants was associated with a lower probability of a psychiatric ER visit (p < 0.05 for all).

Discussion

This retrospective database analysis used medical and outpatient prescription drug claims of a cohort of Medicaid enrollees to evaluate the characteristics and healthcare resource utilization and associated costs of patients with BP-I who experienced FPI in a 12-month period (year 1). FPI was found to be associated with higher subsequent (year 2) healthcare costs as well as higher odds of psychiatric hospitalization and ER visits. The differences in outcomes during year 2 between patients with and without FPI were both statistically significant and sufficiently large to be clinically meaningful.

The relationship between FPI and outcomes is unlikely to be causal. A more plausible explanation is that FPI indicates poorly controlled BP-I, which may lead to higher healthcare service utilization and costs. Adherence to treatment has been reported as a major determinant of outcomes for patients with BP-I; non-adherence and partial adherence both appear to play a significant role in relapse, with non-adherence to medication protocols being the most frequent cause of relapse for patients with BPDCitation15,Citation16. A productive direction for future research might be to investigate the association among treatment adherence, frequency of psychiatric interventions and subsequent healthcare utilization and costs.

In a retrospective analysis of electronic prescription and medical claims representing approximately 1.4 million managed-care commercial health plan members with mental health benefits, Lew et al. found that reduced adherence (<80%) to traditional mood-stabilizing therapy in patients with BP-I was associated with significantly greater risk of psychiatric emergency department visits (odds ratio [OR] 1.98; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.38–2.84) and hospitalizations (OR 1.71; 95% CI 1.27–2.32), after adjusting for age, gender and co-morbidityCitation17. In a study examining the risk of relapse following hospitalization for BP-I, Hassan and Lage found that greater medication adherence (≥75%) was associated with significantly lower odds of any rehospitalization (OR 0.730; 95% CI 0.580–0.919) or of psychiatric rehospitalization (OR 0.759; 95% CI 0.603–0.955)Citation14. These results suggest that patients with FPI are likely to have suboptimal treatment adherence and thus may be more likely to experience CSEs such as psychiatric hospitalization and emergency department visits.

This analysis has several limitations. First, the analysis is based on a convenience sample of Medicaid enrollees in several geographically dispersed states; it is not a random sample of the entire US Medicaid population. Second, because the present study analyzed administrative claims data, several assumptions were made, including that clinical diagnoses are accurate, that medical codes are entered correctly and that a prescription filled is a prescription used. A third caveat to consider is that two of the CSEs used to indicate FPI (psychiatric hospitalizations and ER visits in year 2) were modeled as outcome measures, although these events were assessed at two different points in time and were therefore not simultaneously determined.

In summary, this study finds that FPI is common among patients with a BP-I diagnosis occurring in 53.0% of patients in year 1, and with 28.6% having FPI in year 2 as well. In addition, FPI is associated with higher subsequent healthcare costs as well as higher odds of psychiatric hospitalization and ER visits. These results suggest that interventions targeting BPD patients with FPI may yield not only clinical improvements but also potentially significant cost savings.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, funded this study.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

E.D. and E.B. have disclosed that at the time of this analysis, they were employees of Thomson Reuters, a company that was contracted by Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, to conduct this study. E.M., J.C.C., R.D. and C.C. have disclosed that they are employees of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, and Johnson & Johnson stockholders. J.T.H. has disclosed that he is an employee of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development and a Johnson & Johnson stockholder. W.M. has disclosed that he was an employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, at the time of this analysis.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (26.3 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the technical and editorial support provided by Matthew Grzywacz, PhD, of ApotheCom. The authors also thank Kristina Yu-Isenberg, RPh, PhD, formerly an employee of Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC, for her input during the conduct of this study.

Notes

*MarketScan is a registered trademark of Thomson Reuters (Healthcare) Inc.

References

- Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA 1990;264:2511-2518

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994;51:8-19

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:807-816

- Jamison KR. Suicide and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61(Suppl 9):47-51

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000

- Merikangas KR, Akiskal HS, Angst J, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of bipolar spectrum disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:543-552

- Gardner HH, Kleinman NL, Brook, RA, et al. The economic impact of bipolar disorder in an employed population from an employer perspective. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:1209-1217

- Guo JJ, Keck PE, Hong L, et al. Treatment costs and health care utilization for patients with bipolar disorder in a large managed care population. Value Health 2007;11:416-423

- Stensland MD, Jacobson JG, Nyhuis A. Service utilization and associated direct costs for bipolar disorder in 2004: an analysis in managed care. J Affect Disord 2007;101:187-193

- Brook RA, Klainman NL, Rajagopalan K. Employee costs before and after treatment initiation for bipolar disorder. Am J Manag Care 2007;13:179-186

- Haskins JT, Macfadden W, Turner N, et al. Clinical characteristics and resource utilization of patients with bipolar disorder who have frequent psychiatric interventions. J Med Econ 2010;13:552-558

- Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1075-1079

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373

- Hassan M, Lage MJ. Risk of rehospitalization among bipolar disorder patients who are nonadherent to antipsychotic therapy after hospital discharge. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2009;66:358-365

- El-Mallakh RS. Medication adherence and the use of long-acting antipsychotics in bipolar disorder. J Psychiatr Pract 2007;13:79-85

- Colom F, Vieta E, Martínez-Arán A, et al. Clinical factors associated with treatment noncompliance in euthymic bipolar patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2000;61:549-555

- Lew KH, Chang EY, Rajagopalan K, et al. The effect of medication adherence on health care utilization in bipolar disorder. Manag Care Interface 2006;19:41-46