Abstract

Objective:

Zoledronic acid (ZOL) reduces the risk of skeletal related events (SREs) in hormone-refractory prostate cancer (HRPC) patients with bone metastases. This study assessed the cost effectiveness of ZOL for SRE management in French, German, Portuguese, and Dutch HRPC patients.

Methods:

This analysis was based on the results of a randomized phase III clinical trial wherein HRPC patients received up to 15 months of ZOL (n = 214) or placebo (n = 208). Clinical inputs were obtained from the trial. Costs were estimated using hospital tariffs, published, and internet sources. Quality adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained were estimated from a separate analysis of EQ-5D scores reported in the trial. Uncertainty surrounding outcomes was addressed via univariate sensitivity analyses.

Results:

ZOL patients experienced an estimated 0.759 fewer SREs and gained an estimated 0.03566 QALYs versus placebo patients. ZOL was associated with reduced SRE-related costs [net costs] (−€2396 [€1284] in France, −€2606 [€841] in Germany, −€3326 [€309] in Portugal and −€3617 [€87] in the Netherlands). Costs per QALY ranged from €2430 (Netherlands) to €36,007 (France).

Conclusions:

This analysis is subject to the limitations of most cost-effectiveness analyses: it combines data from multiple sources. Nevertheless, the results strongly suggest that ZOL is cost effective versus placebo in French, German, Portuguese, and Dutch HRPC patients.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide, and is often highly symptomaticCitation1–3. Up to 80% of patients with advanced prostate cancer develop bone metastasesCitation1,Citation4,Citation5. Median survival from the time patients develop bone metastases ranges from 12 to 53 monthsCitation6. Bone metastases can cause considerable skeletal morbidity and lead to skeletal related events (SREs), including bone pain, pathologic fractures, spinal cord compression, and hypercalcemia of malignancy (HCM). These SREs are clinically relevant sequelae and are associated with high healthcare costs and poor quality of lifeCitation7–9. The national cost burden for patients with metastatic bone disease was estimated at $12.6 billion, which is 17% of the $74 billion in total direct medical cost for cancer estimated by the National Institutes of Health, suggesting the significant contribution of metastatic bone disease to the overall oncology costCitation9. In a retrospective costing study using a large US health insurance claims database in patients with bone metastases from prostate cancer, the estimated per-patient SRE-related cost was approximately $12,469Citation10. Radiotherapy accounted for the greatest proportion of cost (47%) by SRE type, resulting in an expense of $5930 per patientCitation10.

Bisphosphonates are widely used to prevent SREs in patients with bone metastases secondary to solid tumorsCitation11. However, zoledronic acid is the only bisphosphonate proven to safely and effectively reduce SREs in hormone-refractory prostate cancer (HRPC) patients with bone metastasesCitation6,Citation12. Without bisphosphonate treatment, approximately 50% of patients with prostate cancer will develop ≥1 SRE within 2 yearsCitation13.

The efficacy for zoledronic acid has been evaluated in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter, phase III trial in patients with HRPC, at 15 monthsCitation1 and 24 monthsCitation14. Eligible patients had HRPC with a documented history of bone metastases, and had three consecutive increasing serum prostate-specific antigen measurements (PSA), taken at least 2 weeks apart, with the third measurement being greater than or equal to 4 ng/ml and taken within 8 weeks of the first visit, had serum testosterone levels within the castrate rate (<50 ng/Dl)Citation1,Citation14, and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) status of ≤2.

In this trial, zoledronic acid 4 mg was associated with a lower incidence of skeletal complications and lower skeletal morbidity rate than placeboCitation1,Citation14. Significantly fewer patients in the zoledronic acid group than placebo group experienced at least one SRE at 15 and 24 months (p < 0.05). A multiple event analysis showed a 53% reduction in the risk of experiencing an SRE with zoledronic acid compared with placebo (RR = 0.47; p < 0.05)Citation15. At 15 months, the median time to the first SRE was not reached in the zoledronic acid group compared to 321 days in the placebo group (not significant)Citation1, and after 24 months in a separate extension study, the median time to first SRE was approximately 6 months longer for 4 mg zoledronic acid than the placebo group (p = 0.011)Citation14.

The purpose of the present analysis was to estimate the cost effectiveness of zoledronic acid versus placebo in HRPC patients with bone metastases. The analysis was conducted using the perspective of two large European countries (France and Germany) and two other, smaller markets (Portugal and the Netherlands).

Material and methods

Study design

A literature-based decision-analytic model was developed to compare the estimated direct costs and benefits of 4 mg zoledronic acid administered via IV infusion every 3 weeks in HRPC patients with bone metastases from the perspective of payers in the four countries. The main outcome measure was the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of using zoledronic acid versus placebo, which calculates the incremental costs (or savings) associated with the use of zoledronic acid to gain one additional quality adjusted life-year (QALY). The analysis included direct medical costs associated with the interventions, including zoledronic acid drug costs, drug administration and supplies, labor costs, and the direct medical costs of treating SREs. Indirect costs such as loss of productivity incurred by the patients were excluded, given that the analysis adopted a payer perspective and that the median age of the patients in the trial was 72 years (i.e., it was assumed that the majority would be retired or unable to work due to advanced disease); hence productivity loss, in terms of wages lost, would be small.

The present analysis was based on the data from the Saad et al. (2002) study, a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter, clinical trial of zoledronic acid in patients with bone metastases from HRPCCitation1. In this trial, patients were randomized to receive zoledronic acid (4 mg or 8/4 mg) or placebo every 3 weeks for 15 months. SREs and adverse events were recorded every 3 weeks. Since the approved dosage is 4 mg, the present pharmacoeconomic analysis focused on the outcomes observed in the placebo and the 4 mg zoledronic acid groups for data. Patients within the 4 mg zoledronic acid and placebo arms had a mean age of 71.8 (±7.9) and 72.2 (±7.9), mean time since cancer diagnosis of 62.2 months (±43.5) and 66.6 months (±46.9), and mean time since bone metastasis diagnosis of 23.8 months (±26.1) and 28.4 months (±30.7), respectively. Proportions of patients with a previous SRE were 30.8% and 37.5% within 4 mg zoledronic acid and placebo arms, respectively. The analysis was based on the entire 15 months. Data from the 24-month extension study were not considered given that that QALY data from Reed et al. were calculated within a 15-month purview.

Survival, SRE rate, number of infusions administered, and quality-adjusted survival were obtained from the clinical trialCitation1. All assumptions related to the gain in QALYs associated with the use of zoledronic acid versus placebo were based on the analysis conducted on this trial by Reed et al. (2004)Citation16. In this economic study of zoledronic acid in the United States, the author reported that the average incremental gain in quality adjusted time during the study period was approximately 2 weeks for patients receiving zoledronic acid (compared to placebo). However, the precise QALY gain was not reported. To derive the gain in QALY on the basis of Reed et al.Citation16, we relied on additional results reported by these authors. Specifically, they reported that the nominal cost-effectiveness ratio was estimated at $159,200 (per QALY gained). From this paper, it is also possible to estimate the incremental costs associated with zoledronic acid at $5353. From these two figures, the QALY gained was estimated as $5353 divided by $159,200, that is, approximately 0.033624 or 12.3 quality-adjusted days (the discrepancy in QALYs gained between this value and that used in our analyses/reported by Reed et al.Citation16 is due to rounding error).

Clinical inputs

As observed during the trial, the median overall survival for the zoledronic acid treatment group was 546 days and 464 days for the placebo groupCitation1. The median overall survivals for ZOL and placebo groups were included in this analysis; although their difference was not significant (p = 0.091). Mean survival (patient-years lived) was then calculated by the following steps for ZOL and placebo groups in a manner consistent with established methodsCitation17,Citation18:

The monthly mortality rate (MMR): MMR = ln (0.5)/Median survival × 365/12

The proportion of patients alive at a given month (% Alive): % Alive = Exp (−MMR) ×% Alive in previous month

Patient-years lived (PY; i.e., mean survival): PY = Sum (% Alive in months 0 to 15)/12 months

The incidence of SREs in patients receiving zoledronic acid or placebo was estimated by multiplying the skeletal morbidity rate (SMR) (i.e., number of SREs divided by the time at risk [PY]) for each SRE type by the estimated mean duration of survival within the 15-month purview of the analysis ().

Table 1. Skeletal morbidity rate in zoledronic acid and placebo groups by SRE type.

Cost inputs

The cost of skeletal events secondary to solid tumors is substantial. However, there is limited literature on the costs of SREs. Particularly, a literature search did not identify any cost estimates for Germany or France. In the present analysis, SRE costs () were estimated on the basis of a combination of literature estimates and government reimbursement tariffs such as diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). These DRGs are designated as GHS (Group Homogène de Séjour) in France, G-DRG in Germany, and HRG (Healthcare Resource Group) in the UK (see Appendix). Cost estimates for SREs in Netherlands and Portugal come from published cost of illness studies (see Appendix)Citation19.

Table 2. SRE costs in four European countries.

Pathologic vertebral fractures may not be symptomatic; hence many never come to clinical attention. Evidence suggests that 34% of vertebral fractures in cancer patientsCitation20 and 33% in the general populationCitation21 are symptomatic, and 7% of fracturesCitation20 in cancer patients and approximately 8% in the general populationCitation21 are managed in the hospital. Hence, the cost of treating a pathological vertebral fracture was assumed to be only 7% of the hospitalization costs.

The costs associated with the use of zoledronic acid (i.e., drug costs, labor costs of administration, and supplies) were included in the analysis () (see Appendix for details of costing methodology). Cost of supplies and labor costs (nurse and physician time) for each infusion were based on a time-and-motion analysis of zoledronic acid administration (see Appendix)Citation22. Zoledronic acid costs were estimated by multiplying the cost of a zoledronic acid infusion in each of the countries by the number of infusions administered during the trial (i.e., 12.6 infusions/patient).

Table 3. Costs of drug, drug administration and supplies per infusion.

All costs were expressed in 2007–2008 prices.

Analyses

To estimate the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, the average total cost of treatment with zoledronic acid (Cz) and placebo (Cp) was estimated along with the average QALYs gained for both the treatment groups (Ez and Ep for zoledronic acid and placebo respectively). The ICER is given by the following formula:

Zoledronic acid was considered cost effective if the ICER was ≤€50,000 – a threshold commonly used in cost-effectiveness analysesCitation23,Citation24. No benefits or costs were discounted because of the short analytical horizon of the model. Univariate sensitivity analyses on individual model input parameters were conducted to assess any uncertainty surrounding the estimate of the cost-effectiveness ratio, i.e. cost per QALY gained. The total cost of infusion (drug + administration costs) was varied by ±10% of the base case as per Reed et al.Citation16. All other parameters were varied by ±25%.

Results

Base case

Total cost of SREs for the placebo group ranged from approximately €5684 to €8392, whereas the total cost of SREs complications for the zoledronic acid group ranged from approximately €3288 to €4775. Compared to placebo, the use of zoledronic acid was associated with a reduction in SRE-related costs (−€2396 in France, −€2606 in Germany, −€3326 in Portugal, and −€3617 in Netherlands) (). After adding the drug and administration costs, zoledronic acid resulted in incremental costs of €1284, €841, €309, and €87 in France, Germany, Portugal, and the Netherlands, respectively.

Table 4. Base-case results.

Sensitivity analyses

Univariate sensitivity analyses were conducted on various model parameters. Threshold analyses were conducted to determine the magnitudes in the changes in model parameters required to alter the conclusion of the analysis (i.e., for the cost effectiveness ratio to reach the €50,000 mark or to become cost neutral: i.e., cost per QALY of €0). These threshold analyses are summarized in . For example, in France, the cost per QALY gained in the base case scenario was €36,007. This ratio increased to the threshold of €50,000 if the QALY gained was reduced by 28.0% (i.e., 1 minus 0.720), if the cost of SREs were all reduced by 20.8%, if the SRE rate in the zoledronic acid group was increased by 15.2%, or if the cost of ZOL or the number of infusions was increased by 13.6%.

Table 5. Threshold values for model parameters to result in cost-effectiveness ratio of €50,000 or neutral costs.

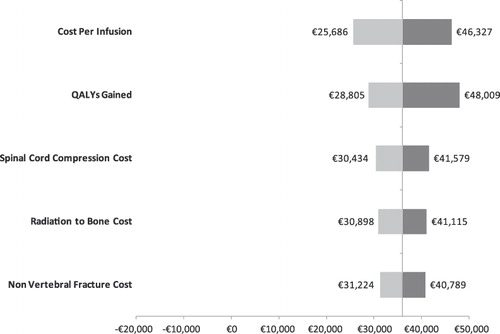

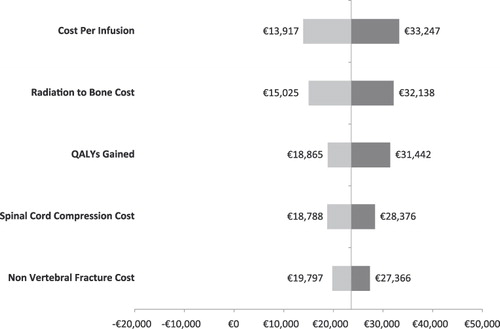

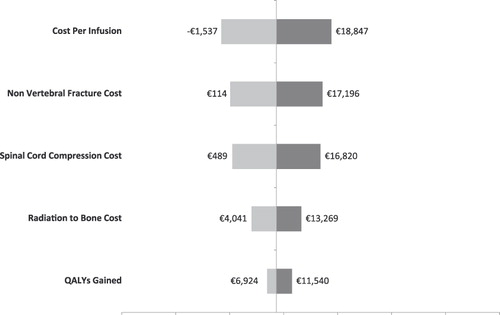

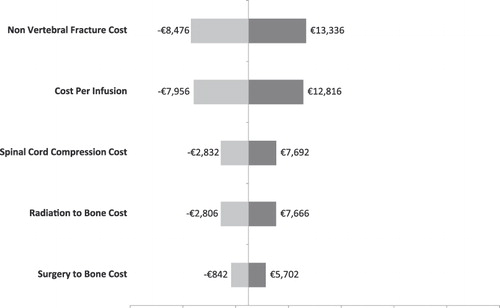

Alternatively, univariate sensitivity analyses are summarized by tornado diagrams in . The variables on the y-axes are rank-ordered such that their relative position indicates the relative ability of a given variable to affect the results of the analysis (e.g., variables higher on the y-axis affect results to a greater extent than do variables lower on the axis). This relationship is also indicated by the numerical distance between minima and maxima values (cost-effectiveness ratios) reported for each variable. In other words, the greater the range between the two cost-effectiveness ratios, the more sensitive the analysis was to that variable. With the exception of the Netherlands, the cost/QALY estimates were most sensitive to the cost per infusion.

Discussion

The present analysis suggests that zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal related events in HRPC patients with bone metastases is cost effective compared to placebo in France, Germany, Portugal, and the Netherlands. The healthcare costs associated with SREs were reduced by €2396 in France, €2606 in Germany, €3326 in Portugal, and €3617 in Netherlands. From Reed et al. zoledronic acid is also predicted to improve HRQoL by preventing painful SREsCitation16. In sensitivity analyses, zoledronic acid remained cost saving or cost effective under various assumptions regarding model inputs.

This analysis is subject to limitations common to all decision analytic models. It combines data from numerous sources, requires structural and data assumptions, and can be subject to potential biases. The costs were indirectly estimated from the observed frequency and types of SRE, and were combined with information collected from various non-trial sources; one being a review of existing DRG payment systems. Cost estimates from DRG systems for France and Germany represent averages across many patient groups, and may not necessarily apply exclusively to metastatic HRPC patients. Also, cost estimates used in this analysis may be subject to underestimation as outpatient costs were disregarded in some instances due to lack of data and uncertainty regarding outpatient treatment patterns. In contrast, cost estimates for SREs in the Netherlands and Portugal came from published cost of illness studies providing potentially more reliable cost estimatesCitation19,Citation25. These cost analyses identified SREs in patients with metastatic, advanced cancer (prostate, breast, and multiple myeloma) and the effect on total treatment cost. Retrospective analyses were performed to study resource utilization and costs associated with skeletal complications in patients with bone metastasesCitation19,Citation25. As such, the results of the Dutch and Portuguese analyses may be more reliable and do suggest that the cost effectiveness of zoledronic acid is positively correlated with the precision of cost estimates.

The results of the present analysis suggest zoledronic acid may be substantially more cost effective in HRPC (with cost per QALY well under the €50,000 mark) than previously reported (cost per QALY of $159,200)Citation16. This difference may be attributed to several factors. Most importantly, the cost estimates associated with SREs used in the present analysis were appreciably higher than in the previous analysis. Specifically, in Reed et al., the total cost of care for SRE- and non-SRE-related resource uses (i.e., including all cancer and non-cancer costs but excluding the cost of zoledronic acid) were estimated at $5365 and $5689 over a 15-month period for the zoledronic acid and placebo arms, respectivelyCitation16. Those estimates may have been very conservative as some estimates of total health care costs for patients metastatic prostate cancer have been estimated by Penson et al. (2004) at $30,626 per year and $92,523 overallCitation26. In addition, Reed et al. reported that the total costs for medical treatment in patients experiencing at least one SRE were $7522 compared to $4180 for patients who did not experience an SRE, which was a statistically significant difference of $3342 per patient (95% CI $1986–4448)Citation16. Since a patient with an SRE may have more than one SRE, the cost per SRE as reported in Reed et al. would likely have been less than $3342. For example, the proportion of patients experiencing any SRE was 44% as reported in Saad et al.Citation1, yet the estimated number of SREs experienced by the average placebo group patient in the present study was 1.59. This would imply that the average number of SREs, conditional on having at least ≥1 SRE, was approximately 3.6 (i.e., 1.59/44%). This consequently implies that the costs per SRE was approximately $900. This figure appears extremely conservative given the range and type of SREs experienced in the trial. In the present study, the cost per SRE avoided were higher (considering the above and differences in exchange rates) and ranged from €144 to €16,289 per event. In addition, the cost of zoledronic acid in the present study (range: €274–294) was less than what was assumed in Reed et al. ($450 per dose). Thus, compared to the estimates herein, Reed et al. used a higher cost of zoledronic acid injections and lower cost of SREsCitation16.

The present analysis included a difference in overall survival between treatment arms despite the fact it was not significantCitation1. This small benefit was included in the QALY estimate. This estimation was provided by Reed et al. on the basis of the trial data, whereby the QALY gained reflected a difference in the number of days the patients were enrolled in the trial, which was assumed to reflect total survival. In absence of other data, this QALY gained was considered acceptable for the present analysis. Had the present analysis excluded the survival difference, the cost effectiveness would likely have not changed considerably because the reduction in QALY would have been accompanied by comparable changes in zoledronic acid utilization and SREs. At the same time, the QALY gained may have been underestimated as it was based on the time spent in the trial rather than total survival.

Despite the above limitations, it is important to place the present results in the broader context of the effectiveness (and cost effectiveness) of zoledronic acid in other solid tumors and other cost-effectiveness analyses in studies of patients with prostate cancer. This agent has been shown to be effective compared to placebo in patients with bone metastases secondary to breast cancerCitation27, other solid tumorsCitation28, and prostate cancerCitation29. Economic studies adopting a European perspective have also shown that zoledronic acid is cost effective (i.e., cost per QALY <€50,000) in breast cancerCitation30,Citation31, lung cancerCitation32, and other solid tumorsCitation33,Citation34.

The present analyses did not include a probabilistic sensitivity analysis because of the lack of reliable inputs (i.e., variance–covariance matrix). Additional research is warranted to comprehensively assess the level of uncertainty around the cost-effectiveness estimates presented herein.

Conclusions

This economic analysis suggests that zoledronic acid therapy is highly cost effective for the prevention of SREs in advanced HRPC. Across all four European countries, zoledronic acid leads to fewer SREs, and better estimated QALY. Within the limits of the evaluation, zoledronic acid consistently appears to be cost effective when compared to placebo. This model suggests that zoledronic acid is a cost-effective treatment that will improve outcomes in patients with advanced HRPC.

Declaration of interest

J.A.C., A.J., and M.F.B. received a consulting fee from Novartis Pharma. S.K. is an employee of Novartis Pharma.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This paper was sponsored by Novartis Pharma.

Acknowledgments

All authors listed in this manuscript have made contributions to the research, data analysis, editing, and manuscript preparation without the input of outside professional services.

References

- Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of zoledronic acid in patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:1458-68

- Parkin DM, Laara E, Muir CS. Estimates of the worldwide frequency of sixteen major cancers in 1980. Int J Cancer 1988;41:184-97

- Parker SL, Tong T, Bolden S, et al. Cancer statistics, 1996. CA Cancer J Clin 1996;46:5-27

- Carlin BI, Andriole GL. The natural history, skeletal complications, and management of bone metastases in patients with prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2000;88(12 Suppl):2989-94

- Pentyala SN, Lee J, Hsieh K, et al. Prostate cancer: a comprehensive review. Med Oncol 2000;17:85-105

- Coleman RE. Bisphosphonates: clinical experience. Oncologist 2004;9 Suppl 4):14-27

- Coleman RE. Skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer 1997;80(8 Suppl):1588-94

- Delea T, Langer C, McKiernan J, et al. The cost of treatment of skeletal-related events in patients with bone metastases from lung cancer. Oncology 2004;67:390-6

- Schulman KL, Kohles J. Economic burden of metastatic bone disease in the U.S. Cancer 2007;109:2334-42

- Lage MJ, Barber BL, Harrison DJ, et al. The cost of treating skeletal-related events in patients with prostate cancer. Am J Manag Care 2008;14:317-22

- Aapro M, Abrahamsson PA, Body JJ, et al. Guidance on the use of bisphosphonates in solid tumours: recommendations of an international expert panel. Ann Oncol 2008;19:420-2

- Garcia-Saenz JA, Martin M, Maestro M, et al. Circulating tumoral cells lack circadian-rhythm in hospitalized metastasic breast cancer patients. Clin Transl Oncol 2006;8:826-9

- Costa L, Lipton A, Coleman RE. Role of bisphosphonates for the management of skeletal complications and bone pain from skeletal metastases. Support Cancer Ther 2006;3:143-53

- Saad F, Gleason DM, Murray R, et al. Long-term efficacy of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with metastatic hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:879-82

- Polascik TJ, Given RW, Metzger C, et al. Open-label trial evaluating the safety and efficacy of zoledronic acid in preventing bone loss in patients with hormone-sensitive prostate cancer and bone metastases. Urology 2005;66:1054-9

- Reed SD, Radeva JI, Glendenning GA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid for the prevention of skeletal complications in patients with prostate cancer. J Urol 2004;171:1537-42

- Beck JR, Kassirer JP, Pauker SG. A convenient approximation of life expectancy (the "DEALE"). I. Validation of the method. Am J Med 1982;73:883-8

- Beck JR, Pauker SG, Gottlieb JE, et al. A convenient approximation of life expectancy (the “DEALE”). II. Use in medical decision-making. Am J Med 1982;73:889-97

- Groot MT, Boeken Kruger CG, Pelger RC, et al. Costs of prostate cancer, metastatic to the bone, in the Netherlands. Eur Urol 2003;43:226-32

- McKean H, Miller RC, Jatoi A. Non-traumatic vertebral fractures in patients with locally advanced esophageal cancer: a previously unreported, unrecognized problem. Dis Esophagus 2007;20:102-6

- Ross PD, Davis JW, Epstein RS, et al. Pain and disability associated with new vertebral fractures and other spinal conditions. J Clin Epidemiol 1994;47:231-9

- DesHarnais CL, Bajwa K, Markle JP, et al. A microcosting analysis of zoledronic acid and pamidronate therapy in patients with metastatic bone disease. Support Care Cancer 2001;9:545-51

- Bell CM, Urbach DR, Ray JG, et al. Bias in published cost effectiveness studies: systematic review. BMJ 2006;332:699-703

- Ubel PA, Hirth RA, Chernew ME, et al. What is the price of life and why doesn’t it increase at the rate of inflation? Arch Intern Med 2003;163:1637-41

- Felix J, Soares M. Treatment costs of skeletal related events in patients with metastatic breast or prostate cancer. 14th European Cancer Conference ECCO. 2007

- Penson DF, Moul JW, Evans CP, et al. The economic burden of metastatic and prostate specific antigen progression in patients with prostate cancer: findings from a retrospective analysis of health plan data. J Urol 2004;171:2250-4

- Kohno N, Aogi K, Minami H, et al. Zoledronic acid significantly reduces skeletal complications compared with placebo in Japanese women with bone metastases from breast cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:331-421

- Rosen LS, Gordon D, Tchekmedyian NS, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of zoledronic acid in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma and other solid tumors: a randomized, phase III, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Cancer 2004;100:261-321

- Meijboom M, Botteman MF, Kaura S. Zoledronic acid is cost effective for the prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with prostate cancer and bone metastases in France and Germany. Poster Presented at the Annual American Urology Association Meeting, 25–30 April, 2009, Chicago, IL, USA, 2009

- Botteman M, Barghout V, Stephens J, et al. Cost effectiveness of bisphosphonates in the management of breast cancer patients with bone metastases. Ann Oncol 2006;17:1072-82

- Logman JF, Heeg BM, Botteman MF, et al. Economic evaluation of zoledronic acid for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer receiving aromatase inhibitors in the UK. Ann Oncol 2010;21:1529-36

- Stephens J, Kaura S, Botteman MF. Cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid versus placebo in the management of skeletal metastases in lung cancer patients: comparison across 3 european countries. Poster Presented at: 45th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology; May 29-June 2, 2009; Orlando, FL, 2009

- Botteman M, Kaura S. Assessment of the cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid in the management of skeletal metastases in lung cancer patients in France, Germany and the United Kingdom. 13th World Conference on Lung Cancer, San Francisco, CA, USA. 8-4-2009

- Marfatia AA, Botteman MF, Foley I. Economic value of Zoledronic Acid versus placebo in the treatment of Skeletal Metastases in patients with solid tumors: The case of the United Kingdom. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2007 ASCO Annual Meeting Proceedings Part I. Vol 25, No.18S (June 20 Supplement) 25 [No. 18S (June 20 Supplement)]. 2007

- Durand-Zaleski I. [Economic evaluation of radiotherapy: methods and results]. Cancer Radiother 2005;9:449-51

- Groot MT, Huijgens PC, Wijermans PJ. Cost of multiple myeloma and associated skeletal-related events in the Netherlands. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2004;4:565-72

Appendix

Table A1. Cost of SREs in France.

Table A2. Cost of SREs in Germany.

Table A3. Cost of SREs in Portugal.

Table A4. Cost of SREs in the Netherlands.

Table A5. Cost of drug and drug administration in France.

Table A6. Cost of drug and drug administration in Germany.

Table A7. Cost of drug and drug administration in Portugal.

Table A8. Cost of drug and drug administration in Netherlands.