Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the relationship between drug copayment level and persistence and the implications of non-persistence on healthcare utilization and costs among adult hypertension patients receiving single-pill combination (SPC) therapy.

Methods:

Patients initiated on SPC with angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) + calcium channel blocker, ARB + hydrochlorothiazide, or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors + hydrochlorothiazide were identified in the MarketScan Database (2006–2008). Multivariate models were used to assess copayment level as a predictor of 3-month and 6-month persistence. Three levels of copayment were considered (low: ≤$5, medium: $5–30, high: >$30 for <90-day supply; low: ≤$10, medium: $10–60, high: >$60 for ≥90-day supply). Separate models examined the implications of persistence during the first 3 months on outcomes during the subsequent 3-month period, including utilization and changes in healthcare costs from baseline. National- and state-level outcomes were analyzed.

Results:

Analyses of 381,661 patients found significantly lower 3-month and 6-month persistence to therapies with high copayments. Relative to high-copayment drugs, risk-adjusted odds ratios at 3 months were 1.29 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.26, 1.32) and 1.27 (95% CI: 1.24, 1.30) for low- and medium-copayment medications, respectively. The strength of the association between copayment and persistence varied across states. Non-persistent patients had significantly more cardiovascular-related hospitalizations (incidence rate ratio [IRR] = 1.36; 95% CI: 1.30, 1.43) and emergency room (ER) visits (IRR = 1.51; 95% CI: 1.43, 1.59) than persistent patients. Non-persistence was associated with significantly larger increases in all-cause medical services cost by $277 (95% CI: $225, $329), but lesser increases in prescription costs by –$81 (95% CI: –$85, –$76).

Limitations:

Limitations include the possibility of confounding from unobserved factors (e.g., patient income), and the lack of blood pressure data.

Conclusions:

High copayment for SPC therapy was associated with significantly worse persistence among hypertensive patients. Persistence was associated with substantially lower frequencies of hospitalizations and ER visits and net healthcare cost savings.

Introduction

Hypertension is a cardiovascular disorder that affects one in three US adults, representing a total direct and indirect cost burden of approximately $73.4 billion in 2009Citation1,Citation2. Appropriate antihypertensive treatment is integral to containing the costs of managing hypertension and related cardiovascular complicationsCitation3. However, monotherapy is often insufficient to effectively lower blood pressure and prevent cardiovascular eventsCitation4,Citation5. According to guidelines, the majority of patients with hypertension require combination therapy with two or more antihypertensive drugs to achieve and maintain target blood pressure, particularly individuals with stage 2 hypertension (systolic pressure ≥160 or diastolic pressure ≥100 mmHg), as well as those with major comorbidities such as diabetes, kidney disease, or heart failureCitation6. The most commonly-prescribed combination therapies consist of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or an angiotensin II-receptor blocker (ARB) combined with either the diuretic hydrochlorothiazide (HCTZ) or a calcium-channel blocker (CCB)Citation7.

Although the use of multiple antihypertensive therapies has increased over the past two decades, the percentage of hypertensive patients with adequate blood pressure control continues to fall below 50% in the USCitation5,Citation8. Poor compliance and non-persistence limit the clinical benefits of therapy, and are considered major barriers to blood pressure goal achievementCitation9. Because polypharmacy and complexity of dosing regimens are factors that contribute to sub-optimal medication-taking behaviorCitation10,Citation11, single-pill combination (SPC) therapies that combine two or more active drugs in a single tablet or capsule have emerged as a more convenient alternative to separate, free-pill combinations of drug components. A meta-analysis demonstrated that the use of SPC antihypertensive therapy is associated with significantly better compliance and persistence compared to equivalent free-pill combinationsCitation12. Large claims database analyses have also reported significantly greater compliance and persistence, as well as lower frequencies of hospitalizations and ER visits and reduced medical services cost, among patients treated with SPC therapyCitation13,Citation14.

For patients who require combination therapy with two or more antihypertensive agents, the use of SPC drugs may reduce the risk of non-persistence to treatment. However, higher copayments for SPC products may limit their realized benefits in improving treatment persistence. Evidence from prior studies suggests that, in hypertension and other chronic illnesses, higher copayments can significantly worsen medication adherenceCitation15–17. A study conducted among new users of antihypertensive therapy found that less-generous drug coverage was associated with a significantly greater likelihood of treatment discontinuationCitation16. Yet the relationship between copayment level and medication-taking behavior has not been assessed specifically among patients requiring SPC therapy. Moreover, limited information is available on the healthcare consequences and economic outcomes of non-persistence among patients treated with SPC drugs. Although previous claims database analyses have examined the relationship between adherence or persistence and health outcomes in hypertension, the studies were confined to patients initiating their first recorded antihypertensive regimenCitation18,Citation19. Consequently, patients receiving multiple-drug combination therapy constituted a small percentage of the study populations (<5%).

Managed care decision-makers require more evidence on the impact of copayment level on treatment persistence and the implications of non-persistence on healthcare outcomes among hypertensive patients receiving combination therapy, for whom continuous treatment may be particularly critical. Moreover, because copayment levels are often designed and enforced at the local level, a comprehensive regional analysis of these outcomes would be informative. Region-specific risk factors, including average income and education level, may influence the extent to which copayment level affects treatment persistence. Differences in clinical practices and patient characteristics across regions may also lead to geographic variations in healthcare outcomes. A comprehensive state-level analysis would help inform region-specific drug formulary decisions by characterizing regional variations in the sensitivity of patients’ healthcare outcomes to drug copayment level and treatment patterns.

The objectives of this study were to investigate the relationship between copayment level for drugs and treatment persistence, and describe the healthcare utilization and cost outcomes associated with non-persistence, among hypertensive patients initiated on recently introduced SPC antihypertensive therapies. Treatment patterns and associated healthcare outcomes were examined at the national and state-specific level.

Patients and methods

Data source

A large, nationwide medical administrative database, Thomson Reuters MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplemental Databases, was used to select study patients. The MarketScan database is an integrated, de-identified, individual-level database that represents the health services of over 107 million unique patients from 1996 to the first quarter of 2009, with 37 million unique patients represented in the 2008 calendar year. Enrollees in the database include employees, dependents, and retirees in the US with primary or Medicare supplemental coverage through privately insured fee-for-service, point-of-service, or capitated health plans. All US census regions are represented in the database. Patients’ enrollment history, demographics, including each person’s 3-digit zip code, claims for medical and pharmacy services, and originally reported cost data were searched and extracted for analyses.

Sample selection

Patients were included in the study if they had a diagnosis for hypertension (ICD-9-CM code 401.xx to 405.xx) and were initiated on an SPC antihypertensive treatments from any of the following therapeutic classes: (1) ARB + CCB (i.e., valsartan or olmesartan plus amlodipine); (2) ARB + HCTZ (i.e., valsartan, candesartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan, or telmisartan plus HCTZ); or (3) ACEI + HCTZ (i.e., benazepril, captopril, enalapril, fosinopril, lisinopril, moexipril, or quinapril plus HCTZ) (). Patients receiving free combination therapy from these drug classes were not included in the study sample due to the potential confounding effect of formulation on treatment persistence. To capture the most recent trends and outcomes, the initiation of ARB + HCTZ and ACEI + HCTZ was identified during the 2-year period from July 1, 2006 to June 30, 2008, allowing the 6-month post-therapy initiation analyses to use the most recently available data up to December 31, 2008. Due to the later availability of SPC treatments with ARB + CCB, the observational window for patients who were initiated on ARB + CCB was shortened to the 1-year period from July 1, 2007 to June 30, 2008.

Table 1. Sample selection process.

Based on pharmacy claims, patients were required to fill at least one prescription for an SPC product in the above-described classes during the observational window. The index date was defined as the date of the first observed fill for an SPC therapy during the observational window. The treatment a patient received on the index date was defined as his or her index therapy, and was defined by its component ingredients (e.g., valsartan/HCTZ). In order to select patients who were newly initiated on the index therapy, we excluded patients with prescription claims for the same SPC treatment within the 6 months before the index date. This criterion, however, did not exclude patients who previously received an SPC therapy with different component ingredients, or who had prior monotherapy with either drug component in the index combination therapy during the same 6-month pre-index period.

In addition, eligible patients were at least 18 years of age on the index date, had continuous enrollment in the database for 6 months before and 6 months after the index date, and had a valid 3-digit zip code in the continental US available in the database.

Variable definitions

Copayment level was determined based on the copayment and days’ supply associated with the index drug fill on the index date. Three copayment levels were possible: (1) low copayment of ≤$5 for <90 days’ supply or ≤$10 for ≥90 days’ supply; (2) medium copayment of >$5 to ≤$30 for <90 days’ supply or >$10 to ≤$60 for ≥90 days’ supply; or (3) high copayment of >$30 for <90 days’ supply or >$60 for ≥90 days’ supply. Low, medium, and high copayment levels were chosen to approximate the difference in patient cost-sharing in commercial/group plans for generic agents (tier 1), preferred branded agents (tier 2), and nonpreferred branded agents (tier 3), respectivelyCitation20.

The primary study outcome was persistence to the index combination therapy during the 6-month post-index period, which was compared between patients with low, medium, and high copayments on the index date. Treatment persistence over 6 months was defined as having no gaps in medication coverage for the index combination therapy exceeding 30 days during the 180-day post-index period. A refill gap of 30 days is a commonly-used threshold for identifying treatment discontinuation in observational databasesCitation14,Citation21. To evaluate the association between copayment for the index therapy and short-term medication-taking behavior, persistence during the 3 months post-index date was also measured and compared between patients by copayment level. Similar to the definition of 6-month persistence, 3-month persistence was defined as any gap in coverage of more than 30 days during the 90 days post-therapy initiation; in addition, patients who received a ≥90-day supply on the index date were considered persistent over 3 months only if they had at least one refill of the index drug within 30 days of the end of supply of the index date fill.

Healthcare utilization and cost outcomes were compared between patients with versus without 3-month persistence to their index combination therapy. This analysis assessed the implications of treatment discontinuation (i.e., non-persistence) during the first half of the 6-month study period (i.e., months 1 through 3 post-index date) on subsequent healthcare outcomes during the second half of the 6-month study period (i.e., months 4 through 6). The purpose of this design was to disentangle the time-ordering of discontinuation and healthcare outcomes by ensuring that treatment discontinuations occurred prior to the outcomes being evaluated.

Several healthcare resource utilization outcomes were measured over 3 months during the second half of the 6-month post-index period, including the numbers of all-cause and cardiovascular-related hospitalizations, emergency room (ER) visits, and outpatient visits. For these outcomes, the type of medical service visit (inpatient, ER, or outpatient) was determined based on the appropriate place of service fields in the MarketScan database. Hospitalizations included claims for inpatient services that were associated with a length of stay greater than 1 day. A medical visit was considered cardiovascular-related if associated with a diagnosis of any of the following conditions or events: cerebrovascular disease (ICD-9-CM: 430.xx-438.xx), congestive heart failure (ICD-9-CM: 398.91, 425.x, 428.xx, 429.3), hypertension (ICD-9-CM: 401.xx–405.xx), hypotension (ICD-9-CM: 458.xx), myocardial infarction (ICD-9-CM: 410.xx), ischemic heart disease (ICD-9-CM: 411.xx–414.xx), peripheral vascular disease (ICD-9-CM: 440.xx–443.xx, 447.1, 557.1, 557.9, V43.4), valvular disease (ICD-9-CM: 394.xx–397.1, 424.xx, 746.3–746.6, V42.2, V43.3), or renal disease (ICD-9-CM: 585.x, 586, V42.0, V45.1, V56).

Healthcare cost outcomes included changes from the pre-index to the post-index period in all-cause medical services cost (i.e., costs associated with inpatient, ER, office, and other visits) and prescription drug cost. The study also examined changes in cardiovascular-related medical services cost, as well as changes in hypertension-related medical services cost and prescription drug cost. For each patient, changes in 3-month healthcare costs were calculated as the difference between costs incurred during the second half of the 6-month post-index period minus half-9 of the costs incurred during the 6 months prior to index therapy initiation. Cardiovascular-related medical services cost was determined based on the same set of ICDcodes used to identify cardiovascular-related healthcare utilization. Hypertension-related costs included medical costs associated with an ICD-9 code for hypertension and prescription drug costs associated with therapies used to treat hypertension. Drug claims were considered hypertension-related if associated with a GPI code beginning with 33 (β-blockers), 34 (calcium channel blockers), 36 (antihypertensives), or 37 (diuretics). Cost outcomes reflected total allowed amount (i.e., insurance payments plus copayments), and were inflation-adjusted to 2008 US dollars using the medical component of the Consumer Price Index.

Statistical methodology

Patients’ demographics and baseline characteristics in 6-month pre-index period, including comorbidity profile, Charlson Comorbidity IndexCitation22, prescription drug use, healthcare service utilization, and healthcare costs, were summarized and compared across copayment levels. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used for continuous variables.

Treatment persistence rates over 3 months and 6 months were compared between copayment levels using multivariate regression analysis to control for differences in baseline characteristics. A generalized partially linear modeling approach was used to compare persistence during 3-month and 6-month post-index periods between patients by copayment level. The models consisted of a linear component, which incorporated patient demographics and baseline characteristics during the 6-month pre-index baseline period, and a non-linear component, which characterized geographic variations in the effect of copayment level on the likelihood of persistence. We used the longitude and latitude of the centroid of each patient’s 3-digit zip code to represent his or her geographical location, and modeled the geographic variation of the copayment effect using a penalized likelihood methodCitation23,Citation24. Regression models controlled for all patient baseline characteristics reported in (excluding healthcare costs).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of patients on single-pill antihypertensive combination therapy by copayment level.

The multivariate models were used to project the expected difference in persistence rates at the patient level. Expected outcomes at the patient level were estimated under the scenarios that all patients paid a low, medium, and high copayment for their index combination therapies, respectively. The projected differences in the probability of persistence between the three scenarios and associated standard errors were computed for each patient. The individual projected differences were then aggregated by each patient’s state and at the national level, and the standard errors of their corresponding aggregated projections were calculated. Differences in the likelihood of treatment persistence between copayment levels were reported in terms of odds ratios.Using a similar approach, generalized partially linear models were employed to evaluate the association between treatment persistence during the first 3 months post-therapy initiation and healthcare outcomes during the subsequent 3-month period, controlling for patient characteristics during the 6-month pre-index period. Projected differences in outcomes between persistent versus non-persistent patients and associated standard errors were calculated at the national level and by state. The effect of persistence on outcomes was presented as incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for healthcare utilization, and as between-group differences for costs.

In all regression analyses, patients’ state of residence was determined based on their 3-digit zip code. Region-specific results were calculated for each of 49 areas in the mainland US, including the 48 continental states and the District of Columbia.

Analyses were conducted using SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Statistical significance was set at a p-value of below 0.05.

Results

Patient baseline characteristics

A total of 381,661 patients initiated on SPC antihypertensive therapy met the study eligibility criteria, including 22,835 on ARB + CCB, 201,924 on ARB + HCTZ, and 156,902 on ACEI + HCTZ (). In the continental US, sample sizes per state ranged from 107 to 43,761 patients, with the median state having 4307 eligible patients treated with an SPC drug.

The numbers of patients by copayment level for their index combination therapy were: 136,597 (35.8%) for therapies with low copayment, 188,401 (49.4%) for therapies with medium copayment, and 56,663 (14.8%) for therapies with high copayment. The percentage of patients who incurred low, medium, and high copayments varied by index drug class (respectively, ARB + CCB: 27.2%, 38.6%, 34.2%; ARB + HCTZ: 21.8%, 54.4%, 23.8%; ACEI + HCTZ: 55.1%, 44.4%, 0.5%). Differences in baseline characteristics of patients at each copayment level were statistically significant, but small in magnitude (). Patients using SPC drugs with low copayments were older on average (58.8 years vs. 55.6 and 55.8 years for the medium and high copayment levels, respectively), and were more likely to be elderly (29.8 vs. <20.0% for the other groups) (both p < 0.0001). Prevalence rates of cardiovascular-related and other comorbidities varied slightly across the different copayment levels. During the 6-month baseline period, patients initiated on low-copayment drugs incurred significantly lower all-cause total healthcare costs compared to those who started on medium- and high-copayment medications ($3962 vs. $4144 and $4403 respectively, p < 0.0001).

Copayment level and treatment persistence

Observed rates of persistence over 6 months were 56.7%, 55.0%, and 50.0% for SPC medications with low, medium, and high copayments, respectively. At the therapeutic class level, unadjusted 6-month persistence rates in the low, medium, and high copayment groups were, respectively, 54.3%, 51.6%, and 45.9% for ACEI + HCTZ drugs, 65.8%, 62.4%, and 54.8% for ARB + CCB drugs, and 60.4%, 56.6%, and 49.3% for ARB + HCTZ drugs. Among non-persistent patients, the median time to therapy discontinuation from the index date was 60 days.

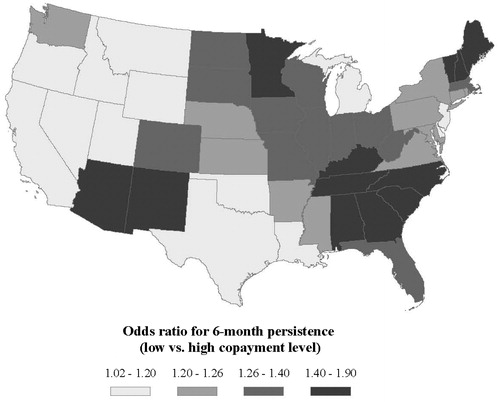

Multivariate analysis found that treatment persistence over 6 months was non-significantly different between the low and medium copayment levels, both at the national level and within 41 of the 49 US states included in the analysis (i.e., all mainland US states, including the District of Columbia) (). Risk-adjusted 6-month persistence rates were 56.1% for patients with low copayments versus 56.0% for patients with medium copayment, for an odds ratio of 1.00 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.99, 1.02). However, the adjusted 6-month persistence rate for patients with high copayments was 49.9%, significantly lower than adjusted persistence rates for the low and medium copayment levels. Relative to high-copayment SPC drugs, the adjusted odds ratio for 6-month persistence with low-copayment medications was 1.28 (95% CI: 1.25, 1.31) (). Low and medium copayments were associated with significantly higher 6-month persistence rates compared to high copayments within 43 and 45 US states, respectively, although the strength of the association between copayment and persistence varied by region. Across different states, the odds ratio for 6-month persistence to medications with low copayments relative to those with high copayments ranged from 1.02 (95% CI: 0.88, 1.17) to 1.90 (95% CI: 1.66, 2.19). maps the state-specific odds ratios of 6-month persistence to medications with low versus high copayments. Differences in 6-month persistence to drugs with medium versus high copayments showed similar geographic patterns (data not shown).

Figure 1. Risk-adjusted comparison of 6-month persistence to medications with low versus high copayment by US state. Odds ratios >1 indicate that medications with low copayment are associated with a higher likelihood of 6-month persistence compared to those with high copayment.

Table 3. Risk-adjusted 3-month and 6-month treatment persistence rates by copayment level*.

Analyses of treatment persistence rates over 3 months yielded consistent results (). Regression-adjusted 3-month persistence rates were 63.3% with low copayment, 63.0% with medium copayment, and 57.3% with high copayment. The adjusted odds ratios for 3-month persistence with low copayment were 1.01 (95% CI: 1.00, 1.03) and 1.29 (95% CI: 1.26, 1.32) relative to the medium and high copayment levels, respectively. Within the majority of states, persistence rates over 3 months were non-significantly different between patients treated with low- versus medium-copayment SPC drugs. However, 3-month persistence rates were significantly higher for patients in the low and medium copayment levels compared to the high copayment group within 42 and 43 of the US states evaluated, respectively.

Treatment persistence and healthcare utilization

Healthcare utilization outcomes were compared between patients with versus without 3-month persistence to their index SPC therapy. After controlling for baseline characteristics, 3-month persistence was associated with significantly fewer all-cause hospitalizations over 3 months compared to non-persistence, both at the national level and within all states evaluated ( and ). The adjusted number of hospitalizations per 100 patients was 3.4 among non-persistent patients compared to 2.6 among persistent patients, resulting in an incidence rate ratio of 1.29 (95% CI: 1.24, 1.33). The adjusted incidence rate ratio for cardiovascular-related hospitalizations (1.36; 95% CI: 1.30, 1.43) showed a similar pattern, and was statistically significant in 48 of the 49 states evaluated ( and ).

Table 4. Risk-adjusted 3-month healthcare utilization among patients with vs. without 3-month treatment persistence*.

Table 5. Risk-adjusted comparison of healthcare outcomes between patients with vs. without 3-month treatment persistence: summary of state-level results.

All-cause and cardiovascular-related ER visits were also significantly more frequent among non-persistent patients at the national level and within the majority of states ( and ). Non-persistence to SPC over 3 months was associated with 34% more all-cause ER visits (IRR: 1.34; 95% CI: 1.31, 1.38) and 51% more cardiovascular-related ER visits (IRR: 1.51; 95% CI: 1.43, 1.59) during the subsequent 3-month period. Additionally, non-persistence was associated with small but significant increases in all-cause outpatient visits (IRR: 1.04; 95% CI: 1.037, 1.045) and cardiovascular-related outpatient visits (IRR: 1.13; 95% CI: 1.12, 1.14) ().

Treatment persistence and healthcare costs

At the national level and within most states, multivariate analysis found that non-persistence to therapy was associated with greater increases in 3-month medical services costs, as measured by changes in costs from the baseline to the study period ( and ). From baseline, non-persistence was associated with an increase in all-cause medical services cost of $245 per patient while persistence was associated with a decrease of $32 per patient, indicating an additional cost increase of $277 (95% CI: 225, 329) among non-persistent patients. On average, patients who were non-persistent to SPC therapy also had additional increases of $196 (95% CI: 155, 237) and $92 (95% CI: 66, 118) in 3-month cardiovascular-related and hypertension-related medical services costs, respectively.

Table 6. Risk-adjusted changes in 3-month healthcare costs among patients with vs. without 3-month treatment persistence*.

However, non-persistence was associated with lesser increases in 3-month prescription drug costs from the baseline to the study period, both nationally and within most regions ( and ). Adjusted results indicated that increases in all-cause and hypertension-related prescription drug costs were lower among non-persistent patients by –$81 (95% CI: –85, –76) and –$45 (95% CI: –46, –44), respectively, compared to persistent patients.

Discussion

Prior research suggests that simplifying dosing regimens through SPC antihypertensive therapy is an effective approach for improving medication-taking behavior among patients with hypertensionCitation12,Citation14,Citation25–29. However, high out-of-pocket costs for SPC drugs may be a barrier to treatment persistence. This study retrospectively examined the relationship between drug copayment level and persistence to antihypertensive combination therapy, as well as the implications of non-persistence on healthcare utilization and costs, using a large, nationally representative sample of managed care enrollees.

Although several studies have examined the effect of copayment for antihypertensive therapy on treatment patternsCitation15–17, this is the first study to characterize the relationship between copayment and persistence specifically for patients initiated on SPC therapy. A previous study conducted by Taira et al. (2006) among patients treated with antihypertensives reported that adherence to antihypertensive medications varied significantly across all copayment levels, as defined by formulary tier (tier 1, tier 2, or tier 3)Citation15. In contrast, the present study found that differences in persistence between the low (≤$5 for <90 days’ supply, ≤$10 for ≥90 days’ supply) and medium (>$5 to ≤$30 for <90 days’ supply, >$10 to ≤$60 for ≥90 days’ supply) copayment levels were minimal, but detected significant differences between the low and medium versus high (>$30 for <90 days’ supply, >$60 for ≥90 days’ supply) copayment levels. Results suggest that hypertension patients who require antihypertensive combination therapy may be less sensitive to the increase in out-of-pocket costs from the low- to medium-copayment levels, but still demonstrate significantly reduced persistence to medications with high copayments. It is also possible that the results reflect patients’ evolving acceptance of higher drug copayments as health plans continue to increase levels of copayments for branded drugs.

At the national level, risk-adjusted treatment persistence rates over 6 months were 56.1%, 56.0%, and 49.9% among patients who incurred low, medium, and high copayments for their SPC therapy, respectively. Based on analyses of short-term, 3-month persistence rates, significant differences in persistence between the copayment levels emerged during the first 3 months post-therapy initiation. Persistence results at the detailed regional level were generally consistent with national-level trends in terms of direction and statistical significance. However, the magnitude of the association between copayment level and persistence varied considerably by US state. Factors specific to certain regions, including income level and age distribution, may explain geographic variation in the strength of high copayment as a predictor of poor treatment persistence. Results strongly suggest that, in order to maximize the clinical benefits of SPC therapy for hypertensive patients, copayment price-setting decisions and patient copayment assistance programs should be tailored according to the region-specific association between copayment level and treatment persistence.

Hypertensive patients receiving combination therapy have been underrepresented in prior studies examining the impact of medication adherence or persistence on healthcare outcomesCitation18,Citation19,Citation30. Compared to hypertension patients receiving monotherapy, those requiring more than one antihypertensive agent are likely to be more difficult to treat and have longer disease history. Persistence to therapy may be particularly important for hypertension patients who initiate on an SPC regimen. In the present study, non-persistence during the first 3 months of therapy was significantly associated with poorer healthcare resource utilization outcomes during the subsequent 3-month period, including notably higher frequencies of all-cause and cardiovascular-related hospitalizations and ER visits. Findings suggest that the difference in cardiovascular outcomes between patients with versus without persistence to SPC therapy becomes apparent after a short period of time. By comparison, in their study among hypertensive patients newly-initiated on treatment (95.7% on monotherapy), Perreault et al. (2010) found that that high adherence had a significant association with reduced risk of coronary artery disease events after at least 1 year of follow-up, but did not find a significant association before the 1-year markCitation19.

While non-persistence to antihypertensive therapy is probably an important source of avoidable healthcare expenditures, few studies have described the relationship between persistence and cost outcomes in this disease area. The present study found that non-persistence was associated with significantly greater increases in medical services cost, which outweighed the prescription drug cost savings. Previous research conducted by McCombs et al. (1994) similarly reported that interruption of antihypertensive therapy was associated with additional medical service expenditures following treatment initiationCitation18. However, the authors noted as a study limitation that the analysis did not consider the temporal relationship between the interruption of therapy and the healthcare costs incurred; thus, costs incurred prior to treatment discontinuation would be misattributed to the discontinuation eventCitation18. We took efforts to overcome this methodological challenge by examining the association between persistence during the first 3 months on healthcare costs during the subsequent 3-month period. Using this approach, cost outcomes were consistent with prior evidence linking non-persistence with significant increases in all-cause medical services costs.

This study also provides new information on the association between persistence and disease-specific medical services costs. Evidence of the impact of compliance or persistence on hypertension-related costs has been inconclusive, potentially due to the smaller available patient samples in earlier studiesCitation31,Citation32; for example, one retrospective analysis noted that while hypertension-specific medical costs tended to be lower among patients with high levels of adherence, this trend was not statistically significantCitation31. The present study, which benefits from a large sample size and relatively recent data from 2006 to 2008, did detect a significant relationship between persistence and reductions in hypertension- and cardiovascular-related medical services cost. Persistence was similarly associated with significant economic savings in both all-cause and disease-specific medical costs within most continental US states, suggesting the generalizability of nation-level cost findings.

Limitations

This study is subject to the usual limitations of retrospective claims database analyses. Due to its observational design, the study cannot confirm causal relationships between copayment level and persistence, or between persistence and healthcare outcomes. There may be unobserved differences in baseline characteristics between comparator groups that could not be fully controlled. Socioeconomic factors may have affected therapy initiation decisions as well as persistence outcomes; for example, patients with higher incomes may be more likely to initiate medications with high copayments and less likely to discontinue treatment due to financial concerns. In the case of systematic differences in income level across the copayment categories, results may understate the correlation between copayment and persistence. In addition, although regression analysis controlled for a comprehensive selection of baseline variables, including demographics, geographic region, comorbidity profiles, and prior resource utilization, potential confounders such as blood pressure level, disease duration, and underlying reasons for treatment choice may have influenced the comparison of outcomes between patient groups. However, every effort was made to adjust for differences in clinical severity through proxy indicators, including baseline hypertension-related medical service utilization and prescription drug use.

Persistence was determined from pharmacy dispensing data; information on actual consumption of medication by patients was not available in the claims database. Copayment level was assigned based on original cost data before the application of any copayment reimbursement coupons, which may have been available for medications in the higher tiers. To the extent that some patients in the high copayment group received partial rebates for their out-of-pocket drug costs, the models are likely to underestimate the association between copayment level and persistence.

Due to the lack of clinical data in administrative claims, the relationship between persistence to SPC therapy and blood pressure control could not be assessed. Limited data availability also prevented the analysis of indirect cost outcomes. Work productivity loss and caregiver’s time may constitute a significant portion of the costs associated with non-persistence.

This study was restricted to patients who initiated on select antihypertensive SPC therapies. In order to study frequently-prescribed combination therapies for which SPC formulations have recently become available, we focused specifically on the ARB + CCB, ARB + HCTZ, and ACEI + HCTZ therapeutic classes. Thus, the results do not provide information on patients treated with other classes of antihypertensive combination therapies, including ACEI plus CCB and β-adrenoceptor antagonist plus HCTZ combinations.

Patients in this study were required to be continuously enrolled in the database for at least 6 months following the initiation of their SPC therapy. The use of a 6-month follow-up period rather than a longer time horizon had the advantage of increasing the available sample size, which permitted a comprehensive region-level analysis of outcomes and the inclusion of patients treated with newly-approved single-pill ARB + CCB therapies. However, additional research is needed to examine the long-term clinical and economic implications of non-persistence among hypertensive patients.

Definitions of the low, medium, and high copayment levels were selected to approximate dollar copayments incurred by patients in a 3-tier commercial/group health planCitation20. However, because copayments vary across health plans, the results of the present study should be interpreted in view of the dollar ranges used to define each copayment level. The observed differences in persistence between the low, medium, and high copayment levels may not be generalizable to health plans that apply different patient cost-sharing requirements.

Conclusions

This large, retrospective analysis demonstrated that high copayment was a significant predictor of reduced persistence in hypertension patients initiated on SPC antihypertensive therapy at both the national level and within most US states. The strength of the association between copayment level and persistence varied considerably across different regions. Treatment persistence was associated with significant benefits, including substantially lower frequencies of all-cause and cardiovascular-related hospitalizations and ER visits. Patients who were persistent to SPC therapy also demonstrated significantly greater decreases in medical services cost from the pre-index to the post-index period, which more than offset small increases prescription drug costs. Cost outcomes linked treatment persistence with net economic savings in both all-cause and disease-related total healthcare costs. Results have important policy implications, suggesting that pharmacy benefit decisions may influence persistence to antihypertensive combination therapy, an important determinant of healthcare utilization and cost outcomes in hypertension patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funding for this research was provided by Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ, USA.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

W.Y., Kristijan H.K., T.F., J.O., and J.C. are employees of Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, East Hanover, NJ. A.G.B., E.Q.W., C-P.S.F., and A.P.Y. are employees of Analysis Group, Boston, MA, which received funding for this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Amy Rudolph, PhD, Ricardo A Rocha, MD, Craig Plauschinat, PharmD, Marjorie Gatlin, MD, Kim A Heithoff, ScD, Jean Lian, PhD and Chris Zacker, PhD for their critical review of the manuscript and/or discussion of the analyses.

References

- Greenland P, Knoll MD, Stamler J, et al. Major risk factors as antecedents of fatal and nonfatal coronary heart disease events. JAMA 2003;290:891-7

- American Heart Association. Heart Disease & Stroke Statistics: 2009 Update At-a-Glance. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association, 2009. Available at: http://www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/1240250946756LS-1982%20Heart%20and%20Stroke%20Update.042009.pdf [Last accessed July 25 2010]

- Degli Esposti L, Valpiani G. Pharmacoeconomic burden of undertreating hypertension. Pharmacoeconomics 2004;22:907-28

- Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, et al. Value of low dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ 2003;326:1427-31

- Neutel JM. Prescribing patterns in hypertension: the emerging role of fixed dose combinations for attaining BP goals in hypertensive patients. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2389-401

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. The National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health. Available at: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7full.pdf [Last accessed 12 July 2010]

- Chrysant SG. Using fixed-dose combination therapies to achieve blood pressure goals. Clin Drug Investig 2008;28:713-34

- Gu Q, Paulose-Ram R, Dillon C, et al. Antihypertensive medication use among US adults with hypertension. Circulation 2006;113:213-21

- Burnier M. Medication adherence and persistence as the cornerstone of effective antihypertensive therapy. Am J Hypertens 2006;19:1190-6

- DiMatteo MR, Giordani PJ, Lepper HS, et al. Patient adherence and medical treatment outcomes: a meta-analysis. Med Care 2002;40:794-811

- Ruilope LM, Burnier M, Muszbek N, et al. Public health value of fixed-dose combinations in hypertension. Blood Press 2008;17:5-14

- Gupta AK, Arshad S, Poulter NR. Compliance, safety, and effectiveness of fixed-dose combinations of antihypertensive agents. A meta-analysis. Hypertension 2010;55:399-407

- Hess G, Hill J, Lau H, et al. Medication utilization patterns and hypertension-related expenditures among patients who were switched from fixed-dose to free-combination antihypertensive therapy. PT 2008;33:652-66

- Yang W, Chang J, Kahler KH, et al. Evaluation of compliance and health care utilization in patients treated with single pill vs. free combination antihypertensives. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:2065-76

- Taira DA, Wong KS, Frech-Tamas F, et al. Copayment level and compliance with antihypertensive medication: analysis and policy implications for managed care. Am J Manag Care 2006;12:678-83

- Briesacher BA, Limcangco MR, Frech-Tamas F. New-user persistence with antihypertensives and prescription drug cost-sharing. J Clin Hypertens 2007;9:831-6

- Maciejewski ML, Bryson CL, Perkins M, et al. Increasing copayments and adherence to diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemic medications. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:e20-34

- McCombs JS, Nichol MB, Newman CM, et al. The costs of interrupting antihypertensive drug therapy in a Medicaid population. Med Care 1994;32:214-26

- Perreault S, Dragomir A, Roy L, et al. Adherence level of antihypertensive agents in coronary artery disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2010;69:74-84

- The Novartis Pharmacy Benefit Report: 2009/2010 Facts, Figures & Forecasts. Emigh R, ed. 17th edn. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation

- Breekveldt-Postma NS, Penning-van Beest FJ, Siiskonen SJ, et al. Effect of persistent use of antihypertensives on blood pressure goal attainment. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:1025-31

- Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol 1992;45:613-19

- Green PJ. Penalized likelihood for general semi-parametric regression models. Int Stat Rev 1987;55:245-59

- Ruppert D, Wand MP, Carroll RJ. Semiparametric Regression. New York: Cambridge University Press

- Dezii CM. A retrospective study of persistence with single-pill combination therapy vs. concurrent two-pill therapy in patients with hypertension. Manag Care 2000;9(9 Suppl):2-6

- Nissinen A, Tuomilehto J. Evaluation of the antihypertensive effect of atenolol in fixed or free combination with chlorthalidone. Pharmatherapeutica 1980;2:462-8

- Asplund J, Danielson M, Ohman P. Patients compliance in hypertension – the importance of number of tablets. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1984;17:547-52

- Jackson 2nd KC, Sheng X, Nelson RE, et al. Adherence with multiple-combination antihypertensive pharmacotherapies in a US managed care database. Clin Ther 2008;30:1558-63

- Brixner DI, Jackson 2nd KC, Sheng X, et al. Assessment of adherence, persistence, and costs among valsartan and hydrochlorothiazide retrospective cohorts in free- and fixed-dose combinations. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2597-607

- Bramley TJ, Gerbino PP, Nightengale BS, et al. Relationship of blood pressure control to adherence with antihypertensive monotherapy in 13 managed care organizations. J Manag Care Pharm 2006;12:239-45

- Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, et al. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care 2005;43:521-30

- Lynch WD, Markosyan K, Melkonian AK, et al. Effect of antihypertensive medication adherence among employees with hypertension. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:871-80