Abstract

Objectives:

The main aim of this study was to describe the effects of regional organization and performance in managing vaccinations, in the light of the institutional devolution recently introduced in Italy.

Methods:

We analysed (1) the general organization of regions for vaccination programmes, (2) the management of four vaccination programmes (combined measles-rubella-parotitis, varicella for children, influenza, and pneumococcal 23-valent for adults).

First, we conducted preliminary face-to-face interviews with 16 regional managers of the infective disease prevention departments. Subsequently, we sent them a standardized questionnaire to obtain comparable information on general organization and on the four specific vaccination programmes considered. In all, 14 regions were eventually included.

Results:

The survey showed a widespread lack of regional staff involved in the management of vaccinations and a geographical variation in the availability of computerized data collection. We recorded poor coverage for varicella and pneumococcal 23-valent vaccinations compared to MRP and influenza. Prices of the four vaccines varied widely among regions, with only a weak correlation between prices and volumes.

Limitations and conclusions:

The major limitation of the survey was the lack of information available at regional level. The piecemeal diffusion of computerized systems and the widespread lack of sufficient staff should mainly explain this.

Economic incentives could be offered to regions that achieve national targets. Such incentives should encourage collaboration between central and regional authorities consistent with institutional trends in regional devolution.

Key words::

Introduction

Vaccination protects both individuals and the community from infectious diseases, reducing the risk of transmission and circulation of pathogens. The efficacy of many vaccines has been historically proven: smallpox has been eradicated worldwideCitation1, and the complete eradication of polio in Europe was achieved in 2002Citation2.

Diseases for which there have been massive vaccination campaigns have almost been eliminated in Italy as well (e.g., diphtheria) and the incidence of infectious diseases that primarily affect children (e.g., pertussis, measles, parotitis, rubella) has been greatly reducedCitation3. These vaccines, together with some for adults (e.g., seasonal influenza vaccine), are routinely supplied to the population in Italy.

The Italian National Health Service (INHS) is a public service funded by general taxation which provides universal coverage and comprehensive healthcare free at the point of deliveryCitation4. The INHS has three institutional tiers: (1) the Department of Health (DoH), (2) 21 Regional Health Authorities (RHAs) and (3) 171 Local Health Authorities (LHAs). The DoH, at the top, is responsible for national planning and allocation of financial resources among regions. The RHAs, which belong to each of the 19 Italian geographical regions and the two Autonomous Provinces of Trentino Alto Adige (Bolzano and Trento), are governed by elected politicians and have tasks similar to the DoH at regional level. The LHAs, led by general managers appointed by the respective RHA, are committed to providing healthcare services to the population.

Since 2001 a Constitutional LawCitation5 has increased regional autonomy (so-called ‘regionalization’ or ‘devolution’) in healthcare policy, devolving the jurisdiction over healthcare issues from the DoH to the RHAs, which autonomously manage and control the services delivered by their LHAs. Essential Levels of Care (ELC), introduced in 2002, are the healthcare services to be provided throughout the INHS in order to guarantee healthcare homogeneityCitation6. In principle, RHAs can use any extra financial resources of their own to cover additional services, although this is very unlikely to happen in practice, as it requires further taxation, which can be politically very unpopular.

The concept of regional autonomy also applies to vaccination policy. Every 3 years the DoH is expected to release a National Vaccination Plan (NVP), which lists the vaccines included in ELCs (the last one was approved in 2005). RHAs plan vaccination programmes according to the NVP, in order to ensure equity of access to the entire Italian population. The DoH also sets the schedules for compulsory and recommended vaccines in children. Diphtheria, hepatitis B, polio and tetanus vaccines are compulsory for all newborns, while measles, rubella, parotitis, pertussis and Haemophilus influenzae b vaccines are only recommended for childrenCitation7. Varicella vaccine is recommended not only for children but also for adolescents without a history of varicella, and for specific risk groups (e.g., patients with chronic kidney failure) listed in a ministerial memorandumCitation8. Particular attention is paid to measles and rubella vaccinations since, in the past, Italy has shown wide differences throughout the country in terms of incidence and monitoring; a national plan, approved in 2003Citation9, has recommended ≥95% vaccination coverage as a target for children aged ≤2 years.

In the past, healthcare professionals used to vaccinate children at school since pupils were not allowed to attend if they had not been vaccinatedCitation10. This legal obligation was cancelled in 1998Citation11, and as a consequence, the practice of vaccinating children at school has been widely abandoned. Now vaccines are administered through (1) LHA facilities for children and (2) general practitioners (GPs) for adults. Currently, GPs mainly administer influenza and pneumococcal vaccines recommended for persons aged ≥65 years.

Refusal of vaccination has gradually increased in recent years in ItalyCitation12, mainly because of the lower perception of the risk of infectious diseases. Therefore, many RHAs have worked out plans to reduce the number of refusals. These programmes usually involve an interview with parents to investigate the primary reason for refusal; then social services can intervene if the decision is perceived to stem from a needy family situation – if so, the juvenile court may eventually be involved.

Regional autonomy also implies stronger financial accountability, which has led RHAs to develop different economic strategies. Some RHAs have recently started buying vaccines through regional tenders in order to exploit their purchasing power more effectively, while many still buy them through their LHAs. It is worth noting the wide differences in the size of regions – the residential population of these range from 130,000 (Valle d’Aosta) to 10,000,000 (Lombardy) ()Citation13, so these regions have very different potential purchasing powers.

This paper summarizes the main results of a survey comparing the organization and performance of regional vaccination services in Italy. We analysed (1) the general organization of RHAs for vaccinations within prevention services and the implementation of support systems, (2) the management of four vaccinations (combined measles-rubella-parotitis and varicella for children, influenza and pneumococcal 23-valent for adults), selected as an representative sample for evaluating RHA policies.

Methods

The study analysis, which focused on the regional organization of immunization services, was carried out during the period March 2008 to November 2009 and information was updated up to the end of 2008.

Four vaccination programmes included in the ELCs were investigated (combined measles-rubella-parotitis and varicella for children, influenza and pneumococcal 23-valent for adults) since it was considered that they were an interesting ‘basket’ for evaluating RHA policies and performance. These four examples were chosen because (1) the high coverage of combined measles-rubella-parotitis vaccine was mentioned as a priority by the NVP, (2) the need for varicella vaccination was highly debated in Italy, and (3) influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations are the first two examples of the massive involvement of GPs in administering vaccines. Since all these vaccinations are recommended, we thought they might help illustrate potential differences among RHA strategies.

First, the managers of the infective disease prevention departments of 16 RHAs were contacted to introduce our centre, asking them for an informal appointment to explain the main goals and features of the survey. They all agreed to preliminary face-to-face interviews to collect basic information on the management of vaccination programmes included in the ELCs. Subsequently a standardized questionnaire was sent to regional managers (see Appendix) to obtain comparable information on regional organizational procedures and on the four specific vaccinations considered. The questionnaire, pre-tested in all fields and explanatory notes with two participants, was divided into two parts. The first focused on the general organization of RHAs for vaccinations within prevention services, including: (1) types of tasks assigned to their services (planning, coordination, monitoring or supervisory activities) and how many workers were dedicated to vaccinations; (2) implementation of support systems, like computerized immunization registries (CIRs), quality control systems, monitoring of adverse events and refusal of vaccinations; (3) educational plans for healthcare professionals involved in vaccinations. Since many RHA workers are also involved in other prevention activities besides vaccinations, we had to apply the full-time equivalent (FTE) indicator – corresponding to one employee’s full working week (38 hours for a civil servant in Italy) – to estimate the staff actually dedicated to vaccinations.

The second part of the questionnaire included specific information on each of the four vaccination programmes analysed, i.e. their administered volumes and purchase prices. Since those RHAs not yet using regional public procurement were asked to provide only the lowest and highest prices of their local tenders, we calculated the simple mean for the regional price. Then we conducted a linear regression to test the relationship between administered volumes and purchase prices of the four vaccines analysed.

Finally, we gathered the medium- to long-term strategies recommended by regional managers to improve vaccination performance.

To double-check information from the questionnaire, data were presented and discussed with participants at an investigators’ meeting (accredited as a ‘continuing medical education’ workshop) in October 2009.

We excluded two jurisdictions from data analysis (Lazio and Trento) as they did not fill in the questionnaire completely, despite several attempts to collect a minimum data set; so 14 RHAs were eventually included.

Results

Prevention services

The main tasks claimed by RHAs were strategic goal setting (100%), resource management (93%) and coordination (86%) of LHA activities, followed by supervision (79%) and planning (71%).

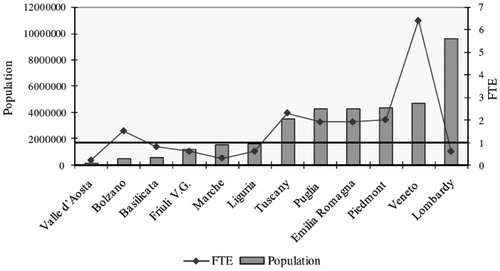

The FTE weighted average for vaccination programmes was estimated at 0.9 per 1 million citizens; it increased in proportion to the residential population in all regions except Veneto and Lombardy (the two largest regions of Italy), which recorded respectively the highest and lowest values ().

Figure 2. Estimated FTE personnel employed for vaccination by RHAs, related to their population. —— = mean FTE per 1,000,000 inhabitants. FTE, full-time equivalent; RHA, regional health authority.

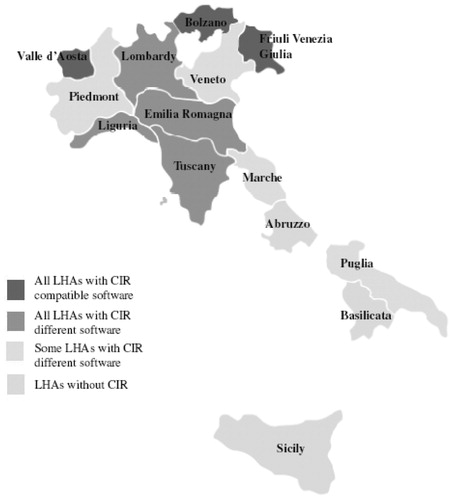

The survey showed a geographical variation in the availability of computerized data collection. In seven regions all LHAs already had a CIR, additionally, three adopting the same software. In four regions not all LHAs had a CIR and also used different software, and in the remaining three the LHAs still had no CIR (). All regions said they collected information on the vaccinations listed in the ELCs. Six RHAs e-mailed data from local to regional authorities, while three others still printed out information and delivered it by mail; the remaining five RHAs did not provide details on data transmission between local and regional authorities.

Figure 3. CIRs in the 14 RHAs analysed. CIR, computerized immunization registry; LHA, local health authority; RHA, regional health authority.

Only two RHAs claimed to have plans for improving the quality of prevention services aimed at better distribution of community centres for vaccination in their territory, and three intended to collect indicators for assessing the quality of services provided.

All but one RHA recorded vaccine adverse events through the normal pharmacovigilance procedure; nine mentioned specific strategies to manage vaccination refusals.

Training plans for local healthcare professionals were organized in all RHAs; courses were mainly for GPs, paediatricians, medical and paramedical vaccination staff of LHAs; only three RHAs supported training programmes for gynaecologists (for HPV vaccination).

Finally, the medium and long-term organizational strategies most cited as having priority were: strengthening CIRs (26%) and improving professional training for healthcare staff (26%); eradication of measles was the most frequent epidemiological target (36%).

Vaccinations

Combined measles-rubella-parotitis (MRP) vaccine

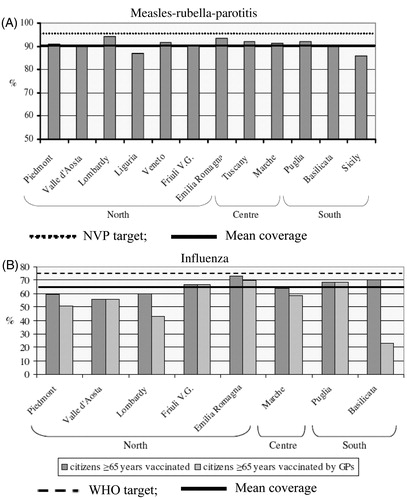

The 12 RHAs that answered this vaccination questionnaire reported high coverage rates (range 86–94.2%) for MRP, although none reached the national target of 95% coverage for infants aged ≤2 yearsCitation9 ().

Varicella vaccine

Two RHAs said they extended this vaccination to additional cohorts – children aged 11 years with no history of varicella (Liguria) and all newborns and children aged 12 years with no varicella anamnesis (Sicily). Nine RHAs were only able to provide quantitative information on the doses administered of this vaccine; most of them recording very low volumes. Puglia, which still administers vaccinations for adolescents mainly at school, was the only RHA which achieved a worthwhile number ().

Influenza vaccine

The mean coverage was 64.7% among the eight RHAs which were able to provide information; only two regions (Emilia Romagna and Basilicata) were over 70%, almost reaching the 75% threshold set by the World Health Organization (WHO) for people aged ≥65 yearsCitation14. GPs administered most of the vaccinations to senior citizens in all but one RHA (Basilicata), where administration was still carried out mainly through LHAs facilities ().

Pneumococcal 23-valent vaccine

Only one region (Friuli Venezia Giulia) reached acceptable coverage for senior citizens (51%), the mean rate being only 2.6% in the other three regions that provided figures. Interviewees suggested that this vaccine was likely to be mainly administered together with influenza vaccine by GPs in the nine RHAs that had signed agreements with general practice for this vaccination also.

Purchase prices

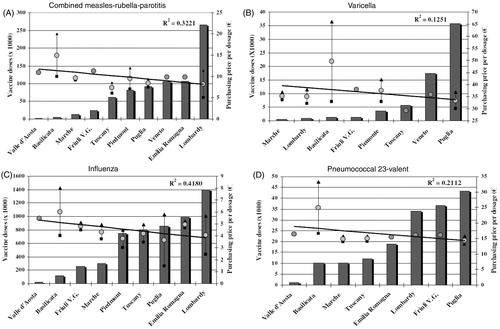

Prices varied widely among RHAs: the highest price was five times the lowest one for influenza vaccines, four times for MRP vaccines, double for pneumococcal 23-valent and varicella vaccines; one RHA (Basilicata) reported by far the highest maximum prices (). Linear regression analysis was conducted to relate the volumes of administered doses to their average price for the RHAs that provided both details. There was a weak correlation between prices and volumes for varicella (R2 = 0.1251) and pneumococcal 23-valent (R2 = 0.2112) vaccines; despite much higher administered volumes, the correlation was also weak for combined MRP (R2 = 0.3221) and influenza (R2 = 0.418) vaccines ().

Table 1. Purchase prices and administered doses of vaccines by RHA (2007).

Discussion

The main aim of this study was to describe the effects of organization and performance of RHAs in managing vaccinations in the light of the regional devolution recently introduced in Italy. In general, regionalization is expected to increase inter-regional variability by enhancing differences between southern and northern regions, the latter being historically wealthierCitation15 and better-organized. To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to shed light on regional management of vaccinations in Italy.

The first potential limitation of this study might be that we did not include all 21 Italian RHAs. However, two-thirds of them were analysed (72% of the Italian population in 2007Citation1Citation6), so the sample should be fairly representative of the country as a whole.

The second and major limitation is the lack of information available at regional level. While managers of infectious disease prevention services seemed highly motivated to take part in the survey – all of them agreed to face-to-face interviews – several pieces of data were missing because of incomplete answers to the questionnaires. Data such as coverage rates or purchase prices were either not known or hard to collect in many RHAs. Therefore, the lack of information available at regional level seems to be one of the main findings of the survey, suggesting that many RHAs do not yet have full control of their LHAs. The piecemeal, uneven distribution of CIRs throughout Italy should explain part of this lack of information. The level of information distribution using compatible computer software among LHAs was adequate only in three small northern RHAs, while in the remaining ones, the CIRs either adopted different local software or were still lacking (particularly in southern regions), a finding which confirms all the concerns raised in a national survey conducted in 2007Citation1Citation7. Heterogeneous local software is likely to stem from the adoption of computer systems in LHAs at different times in the past; later, small RHAs had less difficulty in harmonizing local software than the larger ones. Although LHAs may well manage vaccinations at the local level, a piecemeal situation necessarily jeopardizes the smooth flow of data at regional level. This is probably why many RHA managers see the implementation and development of CIRs as one of their medium- and long-term priorities. Completion of CIRs could facilitate scheduling invitations to families and also the reminders for refusal cases, encouraging adherence to vaccination schemes in the long run.

The lack of sufficient regional staff involved in vaccinations could further explain the lack of information recorded. RHAs have very few employees dedicated to this activity, and many of them count on part-time employees seconded from LHAs (particularly in northern and central Italy). The scarcity of human resources seems to be the major hurdle if RHA managers really expect to cover all the ambitious managerial tasks claimed for vaccinations (planning, coordination, supervision of activities, etc.).

All RHAs are very sensitive towards healthcare professionals’ training, many of them citing improvement as a primary medium and long-term objective as well. Education is expected to strengthen professionals’ communication skills, enhancing the population’s awareness of prevention and adhesion to vaccination schemes.

General high coverage for MRP vaccination was achieved by administering it through LHAs, aiming at the ambitious target set by national authorities to eradicate measles and rubella. The strong commitment to this vaccination programme is confirmed by the lower rates reported in the RHAs whose managers cited measles eradication as their epidemiological priority. The situation for varicella was different. Although we did not quantify coverage rates for this vaccination, as it is hard to identify the target population, in general, administered volumes (in relation to regional populations) were very low indeed. The only RHA that recorded a worthwhile number of doses was the one that still administers vaccines to children at school, a practice that might contribute to this positive result.

Although the target set by the WHO was not achieved in 2007, coverage was satisfactory for adult influenza vaccination in all RHAs, mainly thanks to the involvement of GPs, who are self-employed professionals motivated to administer vaccines by a ‘fee for service’ scheme. In contrast, coverage was very low for the pneumococcal 23-valent vaccine, despite the awareness campaigns run by most RHAs as well as the widespread involvement of general practice for this vaccination.

The poor results for varicella and pneumococcal 23-valent compared to MRP and influenza vaccinations (both administered by LHA staff and GPs) cast doubt on the RHAs’ real commitment to support these vaccinations by RHAs, as emerged informally during many interviews. Most regional managers do not seem fully convinced about the real need for these vaccinations, despite their inclusion in the national ELCs. A clear example of this widespread negative attitude comes from TuscanyCitation18, where an expert panel appointed by the Regional Health Agency estimated an unfavourable cost–benefit ratio for varicella vaccination, supporting the regional decision to administer it only under GP prescription. These poor results suggest that the DoH should strive more to achieve consensus with RHAs in setting priority vaccinations, otherwise many goals stated in the NVP will be difficult to reach.

We found no clear trend for purchase prices, not even for MRP and influenza vaccines which were administered in large numbers. A first general comment is that since infective disease prevention departments do not play a primary role in purchasing procedures – as emerged during preliminary face-to-face interviews – prices are not considered a major issue, which helps explain the lack of information in this specific case. LHA tenders seem to lead to very uneven prices throughout the country, probably thanks to the historical absence of benchmarking inside the INHSCitation19.

In an effort to exploit their purchasing power better, five RHAs have recently switched to centralized public procurement for specific vaccines. Although their prices in our survey did not differ substantially from those of the other RHAs, we still believe that regional tenders should increase RHAs financial accountability and boost transparency. A recent successful example was that of HPV vaccinesCitation20, the ex-factory price negotiated by the Italian Agency for Medicines (AIFA) at central level was more than halved after 2 years, thanks to regional tenders.

Although the Italian landscape historically involves wide regional differencesCitation21,Citation22 and there are no similar analyses of vaccinations for comparison, we feel that devolution has actually helped make the situation more uneven in efficiency and effectiveness, as has been already observed for other healthcare services in the INHSCitation23. More top-down coordination seems needed to achieve satisfactory performance; computerized registries, monitoring coverage rates, and price-volume contracts should be top priorities. With the aim of setting up a ‘virtuous circle’ between central and regional authorities to strengthen vaccination policy in Italy, economic incentives could be offered to RHAs that achieve positive results in relation to targets shared among regions and fixed at national level.

All these suggestions seem to be consistent with the Italian institutional trend of regional devolution.

In conclusion, we think that achieving acceptable effectiveness of vaccination offer and management is an important target in order to see whether devolution constitutes a true progress in healthcare. The last NVP referred to 2005–2007 since the 2008–2010 plan draft was never approved. The 2010–2012 version, currently under discussion, focuses on the need of ensuring universal and homogeneous access to all Italian residentsCitation24. Computerized registries and coverage targets for some essential vaccinations – including MPR, HPV, poliomyelitis, hepatitis B, and seasonal influenza – are among the key actions proposed in the new plan. If the DoH and regions approve this plan within the next few months, this might be an important step towards clearing up the major obstacles currently in the way of vaccination effectiveness in Italy. However, if central and regional authorities fail to reach at least a formal agreement, as happened in the past, the gaps in equal access to vaccinations throughout the country will very likely grow wider in the coming years.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

CESAV received unrestricted grants for contract research and continuing medical education programmes from a few pharmaceutical companies, including the Italian subsidiary of Sanofi-Pasteur MSD. The sponsor had no role in the preparation of this article.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

L.G., A.P., G.C. have no financial/other relationship to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the interviewees of the regional infective disease prevention departments: Tamara Agostini, Claudio Angelini, Emanuela Balocchini, Antonella Barale, Roberto Carloni, Michele Dagostin, Manuela Di Giacomo, Lorenza Ferrara, Linda Gallo, Francesco Lo Curatolo, Giancarlo Malchiodi, Mario Palermo, Maria Grazia Pascucci, Clara Pinna, Rosa Prato, Francesca Russo, Salvatore Scondotto, Luigi Sudano, Giuliano Tagliavento.

However, any opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors alone.

Special thanks go to Katelijne Van de Vooren, for help with manuscript revision.

References

- World Health Organization. The Global Eradication of Smallpox: Final Report of the Global Commission for the Certification of Smallpox Eradication. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 1980

- WHO Europe. Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication. Fifteenth Meeting of the European Regional Commission for the Certification of Poliomyelitis Eradication. Copenhagen, Denmark, 19–21 June, 2002

- Ministry of Health, Italy. Available from URL: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_543_allegato.pdf

- France G, Taroni F. The evolution of health-policy making in Italy. J Health Polit Policy Law 2005:30:169-87

- Legge costituzionale n. 3 del 18 ottobre 2001. Modifiche al titolo V della parte seconda della Costituzione

- Decreto del Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri del 29 novembre 2001. Definizione dei Livelli Essenziali di Assistenza

- Ministry of Health, Italy. Available from URL: http://www.salute.gov.it/malattieInfettive/paginaMenuMalattieInfettive.jsp?menu=vaccinazioni&lingua=italiano

- Circolare del Ministero della Sanità n. 8 del 10 marzo 1992. Indicazioni della vaccinazione antivaricella in categorie di soggetti a rischio

- Conferenza permanente per i rapporti tra lo Stato, le Regioni e le Province Autonome di Trento e Bolzano. Repertorio Atti n. 1857 del 13 novembre 2003. Piano nazionale per l’eliminazione del morbillo e della rosolia congenita 2003-2007

- D.P.R. n. 1518 del 22 dicembre 1967. Regolamento per l’applicazione del Titolo III del decreto del Presidente della Repubblica 11 febbraio 1961, n. 264, relativo ai servizi di medicina scolastica

- Circolare del Ministero della Sanità e della Pubblica Istruzione del 23 novembre 1998. Certificazioni di vaccinazioni obbligatorie

- Gritti S, Padula A, Casadei G. Indagine sulla gestione regionale della prevenzione vaccinale. Quaderni di Farmacoeconomia 2010;12:13-23

- National Institute of Statistics, Italy. Available from URL: http://www.istat.it/salastampa/comunicati/in_calendario/bildem/20100607_00/

- World Health Organization. Available from URL: http://www.who.int/immunization/wer8033influenza_August2005_position_paper.pdf

- National Institute of Statistics, Italy. Available from URL: http://www.istat.it/salastampa/comunicati/non_calendario/20091015_00/

- National Institute of Statistics, Italy. Available from URL: http://demo.istat.it/pop2007/index3.html

- Alfonsi V, D’Ancona F, Ciofi degli Atti ML. Survey on computerized registries in Italy. Annali d’Igiene 2008:20:105-11

- Regional Health Agency, Tuscany, Italy. Observatory for Epidemiology. Valutazione economica di un programma per la vaccinazione contro la varicella nei bambini e negli adolescenti suscettibili, 2007. Available from URL: http://www.epicentro.iss.it/ebp/pdf/Dossier_varicella-ebp.pdf

- Garattini L. Il SSN: Organizzazione, Servizi, Finanziamento. Milano, Italia: Kailash Editore, 1992

- Garattini L, Casadei G. Cure H: far bene la gara fa bene alla spesa. Sole 24 ore Sanità, 26 gennaio, 2010

- Taroni F. Restructuring health service in Italy: the paradox of devolution. In Restructuring Health Service: Changing Context and Comparative Perspective. London, UK: Zed Books, 2003

- D’Ancona F, Alfonsi V, Ciofi degli Atti ML. Survey on vaccination strategies used in different Italian Regions, for the 7-valent conjugate pneumococcal, meningococcal C and varicella vaccines. Igiene Sanità Pubblia 2006;62:483-92

- European Observatory on Health System and Policies Series. In Saltman RB, Bankauskaite V, Vrangbæk K, eds. Decentralization in Healthcare. Strategies and Outcomes. Maidenhead, UK: McGraw-Hill Open University Press, 2007

- Ministero della Salute. Piano Nazionale Vaccinazioni 2010-2012. Available from URL: http://www.sanita.ilsole24ore.com/Sanita/Archivio/Normativa%20e%20varie/Bozza%20PNV28settembre2.pdf?cmd=art&codid=26.0.266865570 [Last accessed 5 July 2011]

Appendix