Abstract

Background:

Poor adherence to medical treatment is one of the main reasons why patients do not achieve the full benefits of their therapy. It also has a substantial financial weight in terms of money wasted for unused medication and increased healthcare costs including hospitalization due to clinical complications.

Objective:

To provide an overview and examples of the financial and economic consequences of poor adherence to treatment, techniques and devices for monitoring adherence and interventions for improvement of treatment adherence.

Results:

New electronic devices with monitoring features may help to objectively monitor patients’ adherence to a treatment regimen that can help a healthcare professional determine how to intervene to improve adherence and subsequent clinical outcome. Interventions that aim to enhance adherence may confer cost-effectiveness benefits in some indications and settings. The nature of the intervention(s) used depends on a range of factors, including patient preference, therapy area and cost of the intervention. However, there is a pressing need for rigorous trials, as current studies often have major flaws in the economic methodology, especially in terms of incremental analysis and sensitivity analysis.

Limitations:

This review has focused on a limited number of therapeutic areas as coverage of a more extensive range of diseases may be beyond the scope of such a summary. Nevertheless, the examples are representative of the challenges encountered in many other diseases.

Conclusions:

The clinical and economic consequences of non-adherence and interventions to improve compliance reflect the nature and severity of non-adherence, as well as the pathophysiology and severity of the disease. Interventions that aim to enhance adherence may confer cost-effectiveness benefits in some indications and settings, and good adherence can help payers and providers contain costs by extracting maximum value from their investment in therapies.

Introduction

Poor adherence is the main factor underlying the failure of many patients, societies and healthcare systems to achieve best treatment outcome. The primary benefit of proper adherence to treatment is an improvement of the disease, while secondary benefits include a reduced incidence of psychosocial complications of disease, more cost-effective use of healthcare resources and enhanced health-related quality of life (QoL)Citation1. In Vienna in November 2009, an advisory board meeting was held to discuss the economic consequences of poor adherence in a number of chronic diseases: diabetes, multiple sclerosis (MS), growth hormone deficiency, asthma, cardiovascular disease, HIV/AIDS and phenylketonuria. Although it is widely accepted that poor adherence is a concern in the majority of diseases, this review presents the discussions of the advisory board, and therefore mainly focuses on these disease areas.

Definitions

Since Hippocrates first counseled physicians to “keep watch … on the faults of the patients, which often make them lie about the taking of things prescribed” in the 4th century BC, patients’ ability to follow advice from their healthcare professionals has been much studied. Several terms have been employed to describe patient behavior towards treatment, one of the earliest being ‘compliance’. Defined as ‘the extent to which a patient acts in accordance with the prescribed interval and dose of a dosing regimen’, compliance suggests that the patient or caregiver passively follows the instructions of the physicianCitation1,Citation2. Considering that a patient will often face conflicting demands on their time into which taking medication fits, a preferred term is ‘adherence’, defined as ‘the extent to which a person’s behavior corresponds with agreed recommendations from a healthcare provider’. This implies that the patient’s agreement with the physician’s recommendations is requiredCitation1. ‘Persistence’ is defined as ‘the number of days from first dose until a patient stops taking a drug’. Recently ‘concordance’ has been used to denote that ‘the prescriber and patient should come to an agreement about the regimen that the patient will take’. A lack of concordance between the patient’s willingness to follow treatment and the practitioner’s prescribing behavior can mean that treatments are offered to patients who are not ready to follow them, leading to poor adherenceCitation1,Citation3.

Consequences of poor adherence

Overall, the World Health Organization estimates that adherence is only around 50% among people taking long-term therapy for chronic diseases in developed countriesCitation1. Strategies that improve adherence could produce great financial and economic benefits by attenuating the effect of risk factors and preventing adverse health outcomes in a wide range of diseases and settings. In some cases, improving adherence with existing drugs could have at least as great an impact on outcomes as introducing new therapeutic agents. Indeed, a Cochrane review concluded: “effective ways to help people follow medical treatments could have far larger effects on health than any treatment itself”Citation4.

This review suggests that the inclusion of costs and consequences associated with poor adherence more systematically in pharmacoeconomic studies should help provide evidence that supports changes to reimbursement structures and facilitates attempts to implement initiatives to improve adherence.

The costs of poor adherence

Poor adherence impairs treatment outcomes and increases healthcare costs. One of the most studied examples in this area is diabetes, which illustrates the clinical and financial impact of various levels of adherence. Self-reported medication adherence independently predicts glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levelsCitation5. In one study, each 10% increase in adherence with anti-diabetic medication reduced concentrations of HbA1c by 0.16%Citation6. Another study reported that each 25% decrease in adherence was associated with an increase in HbA1c concentrations of 0.34%Citation7. Data from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) indicated that each 1% decline in HbA1c concentrations was associated with risk reductions of 14% for myocardial infarctions, 21% for any diabetes-related endpoint, 21% for diabetes-related deaths and 37% for microvascular complicationsCitation8. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) showed that each 10% decline in HbA1c levels reduced the risk of retinopathy progression by approximately 44%Citation9. Based on these data, it seems reasonable to infer that improved adherence will reduce the risk of complications, although this requires confirmation in prospective studies.

Adequate adherence to medications for chronic diseases reduces the risk of relapse or complicationsCitation1. Diabetes is the leading cause of new-onset blindness among working-aged adults and contributes to half of non-traumatic lower limb amputations and around a third of cases of new-onset end-stage renal disease. Furthermore, diabetes increases the risk of developing cardiovascular disease between two- and four-foldCitation10. The growing impact of this disease and its comorbidities is apparent from the worldwide prevalence of diabetes, which could reach an estimated 438 million (a global prevalence of 7.7%) by 2030Citation11. The epidemiological burden of most chronic diseases affects both the developing and developed world. Indeed, the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa and South-East Asia are estimated to have the largest relative increases in the number of cases of diabetes between 2010 and 2030Citation11. Good adherence to anti-diabetic medication is essential to produce adequate glycemic control and, thus, minimize the risk of morbidity and mortality.

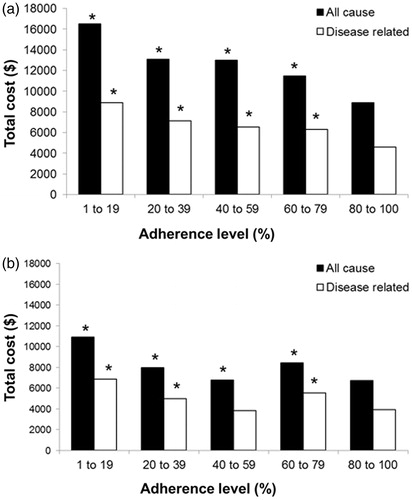

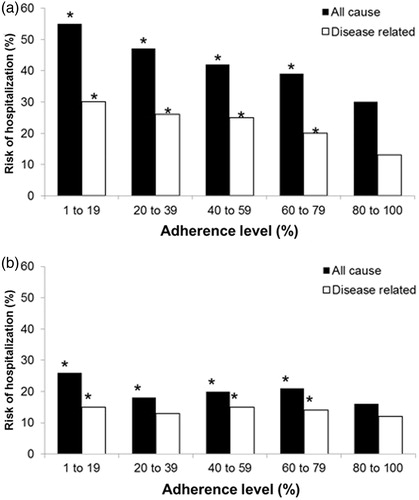

Compelling evidence indicates that poor adherence is common in people with diabetesCitation12–15 and is associated with impaired glycemic control and an increased risk of potentially serious complications. The increased risk of morbidity and mortality associated with poor glycemic control contributes to the considerable costs of managing diabetes. A retrospective study demonstrated that annual related costs for patients with sustained glycemic control (HbA1c ≤ 7.0%) are 32% lower than costs for patients not reaching the target blood-glucose levels (HbA1c ≥ 7.0%) (US$1171 vs. $1540 per patient)Citation16. Over 3 years, managing patients with HbA1c levels of 6% and 10% cost $23,873 and $26,408, respectivelyCitation17. In diabetes and hypercholesterolemia, high levels of adherence offset all-cause total healthcare costs () and risk of hospitalization () is significantly reducedCitation18.

Figure 1. Total healthcare costs for all causes (associated with any condition during the study period) and disease-related costs (a subset of all-cause costs associated with treatment of the target condition). A. Diabetes. B. Hypercholesterolemia. Costs were calculated in a study population of participants in medical and drug benefit plans in the USA over a period of 12 months (n = 137,277). Medication adherence was measured by patients’ overall exposure to medications used to treat a given condition. Adherence was defined as the percentage of days during the analysis period that patients had a supply of one or more maintenance medications for the condition. *Indicates that the medical cost component of the total cost is significantly higher than that for the 80–100% adherence group (P < 0.05)Citation18.

Figure 2. Risk of hospitalization for all causes (associated with any condition during the study period) and disease-related risks (a subset of all-cause costs associated with treatment of the target condition). A. Diabetes. B. Hypercholesterolemia. Risks of hospitalization were calculated in a study population of participants in medical and drug benefit plans in the USA over a period of 12 months (n = 137,277). Medication adherence was measured by patients’ overall exposure to medications used to treat a given condition. Adherence was defined as the percentage of days during the analysis period that patients had a supply of one or more maintenance medications for the condition. *Indicates that the risk of hospitalization is significantly higher than that for the 80–100% adherence group (P < 0.05)Citation18.

As an example in a setting other than diabetes, a nursing intervention that enhanced compliance with antiretrovirals in HIV therapy increased viral suppression by 63% after 48 weeks. The reduction in viral load increased life expectancy (94.5 to 100.9 quality-adjusted life months) and decreased direct lifetime medical costs (between $253,800 and $261,300). The nurse-led intervention to improve adherence was highly cost-effective: the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gained was just $14,100Citation19. Therefore, approaches that improve adherence, and thus outcomes, can be cost-effective, although formal assessments are required.

Quantifying treatment adherence

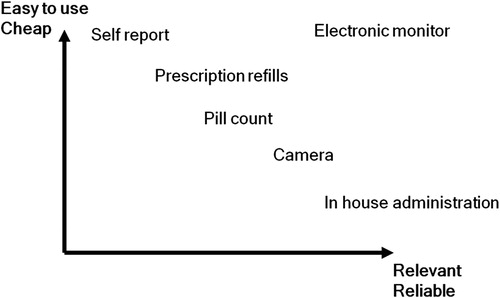

There are many ways to measure adherence and the choice of one versus another can be difficult. The ideal method is cheap, easy to use in clinical practice, relevant, informative and non-invasive. However, none of the currently available methods to measure or assess adherence – which include self-reporting, electronic monitoring, medicine or pill count, pharmacy refill data, claims data, and biological assays measuring levels of drugs metabolites or biomarkers – meet all these criteria ()Citation20. The inexpensive, easy-to-use options can be unreliable and require a high degree of trust in the patient to report. However, the more sophisticated and reliable options, such as insisting that a patient attends a clinic or hospital to receive their medication, may be too expensive, inconvenient or costly in time to be practical.

Figure 3. Trade-off between costs and benefits of various types of adherence monitoring systems (from Norgren S. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2009;6(Suppl 4):545–8. Used with permission)Citation20.

Monitoring of adherence by using traditional methods

Traditional methods of measuring patient adherence include self-reporting (e.g. diaries or questionnaires), pill counting, or noting the frequency of refilled prescriptions. Patient questionnaires and self-reports are simple, inexpensive methods to monitor adherence but, although the most widely used in normal clinical practice and most settings, can be unreliable. For example, changes in the interval between clinic visits and deliberate or inadvertent distortion by patients can result in misleading records of adherence. Pill counts and patient diaries are straightforward in clinical practice; nevertheless, pill dumping or making false entries can produce misleading records of adherence. Data based on the frequency of prescription refills are easy to obtain; however, filling a prescription does not guarantee that the patient has taken the medication. Even when concentrations of a drug are measured in the clinic, pharmacokinetic variations and increased adherence before a clinic appointment may provide a false impressionCitation21.

Electronic tools to support adherence monitoring

Electronic monitoring systems are now available for several delivery methods (examples of which are summarized in ). Only electronic monitors or devices can collect the data that allow healthcare professionals to assess the fine detail of adherence in clinical practice. Patients who use the same overall proportion of prescribed drug taken can show markedly different patterns of adherence. For example, a third of patients take drug holidays, at least occasionally. Adherence is almost ideal in around one-sixth of patients. This proportion of patients take their drug at irregular times or occasionally miss a day. Around one in every 16 patients takes no or occasional dosesCitation21. Furthermore, adherence in many chronic diseases is typically worse at weekends, between April and September, and in association with certain life events, such as when children stay with a friend overnight, educational exams, overuse of alcohol and changes in jobs or homeCitation20. Electronic monitors or devices can provide insights into specific issues and identify opportunities to intervene and address particular problems, such as poor adherence associated with a life event. However, electronic systems can be expensive and may be unsuitable for routine clinical useCitation21.

Table 1. Electronic devices for monitoring treatment adherence in different therapy areas.

The Medication Event Monitoring System (MEMS) is used to monitor usage of oral medication (pills and tablets). This is a pill bottle lid that contains microelectronics to record when it is opened (and closed). This system relies upon the assumption that opening the container is associated with consumption of the dose and correlation with clinical data is required to confirm adherenceCitation22. The system has been extensively used and, since 1989, has been cited by more than 500 peer-reviewed articlesCitation23. In asthma therapy, the Smartinhaler and Doser devices attach to commercial metered dose inhalers and record when they are used to administer a dose. In the case of the former device, data can be downloaded for analysis on a computer, while the latter allows review on the device itselfCitation24,Citation25. While the MEMS and inhaler devices can count the doses of a medication administered to the patient, counts may be misled by the patient disposing of the tablet or not inhaling from the device.

The easypod and RebiSmart are autoinjector devices with a similar design. The easypod is used to administer recombinant human growth hormone (r-hGH) treatment and RebiSmart is used to administer interferon beta-1a for the treatment of MS. To help avoid ‘faked’ doses, they feature a skin sensor, which allows the administration of a dose only when full contact is made. A hidden needle and adjustable comfort settings are integrated for patient convenience. A dose-history feature enables patients and caregivers to see when doses have been administered and missed; a full history can be downloaded by the clinician for analysis of adherence to the treatment regimen and used in discussion with the patientCitation26,Citation27.

Diabetes patients receiving insulin may choose to be treated using an insulin pump, which offers advantages over injection regimens including improved comfort, easier management of infections and hyperglycemia, and better accuracy at low insulin dosesCitation28. In terms of following adherence to treatment regimens, modern automated insulin pumps often have built-in memory to record the doses of insulin supplied from the pump, which physicians may access and review.

Application of methods to measure adherence

A meta-analysis suggested that mean adherence to medical treatments for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) was 68.8%Citation34. Disease management programs for COPD can incorporate one or more of various measures to improve adherence, including self-reporting, inhaler weights, electronic monitoring, inhalation technique assessment, medicine and pill count, pharmacy refill data and claims data, and biological assays. Self-reporting was the cheapest, simplest and easiest method to assess adherence, although this approach is commonly criticized for overestimating adherence and therefore being unreliableCitation34. Moreover, the various methods used to assess adherence can produce markedly different results. For example, one study assessed adherence to beclomethasone dipropionate in 102 asthmatic patients aged between 3 and 14 years. Adherence rates were 97.9% and 70.0% according to self- or parent-report and pharmacy record, respectively. In contrast, adherence rates based on electronic monitoring and canister weight were 51.5% and 46.3%, respectively, suggesting that self-reports overestimate adherence. Furthermore, adherence based on all methods decreased progressively during the 1-year follow-up, underscoring the importance of regular follow-ups. Several factors – including conscious discharging and failure in medication intake – could account for the overestimated adherence based on pharmacy recordsCitation35.

Potential barriers to adherence

Not only is compliance difficult to accurately measure, it can also be due to a variety of reasons, making improvement a complicated process. These reasons vary from socioeconomic causes, such as poor education, to therapy-related causes such as the method of administration (summarized in ).

Table 2. A selection of barriers and interventions to adherence, categorized by type of adherence issue.

Social and economic causes

Several socioeconomic factors associated with poor adherence include economic poverty, illiteracy and low level of education, unemployment, poor social support networks, dysfunctional family relationships, unstable living conditions, cost of transport and medication, as well as incorrect or inappropriate cultural and lay beliefs about illness and treatmentCitation1. All patients can be affected by these factors, regardless of their condition, so it is important that they are considered if positive effects on treatment are not being seen.

Healthcare team and health system causes

Suboptimal performance by healthcare teams in several areas – including a lack of knowledge and training, failure to provide adequate patient education or follow-up – can compromise adherence. Deficient service structures, inadequate reimbursement and medication distribution, excessive workload, lack of incentives and feedback on performance, short consultations and other health system limitations can further exacerbate poor adherenceCitation1.

Therapy-related causes

The side effects of certain drugs and the administration of some formulations (e.g. injectable formulations) can be unpleasant. Non-adherence may also confer other immediate advantages, such as avoiding reminding oneself of the disease and the associated lifestyle disruption. Numerous factors related to drug administration can influence adherence, including the regimen’s complexity, treatment duration, previous therapeutic failures, the frequency of regimen changes, how rapidly benefits emerge and the pattern of adverse effectsCitation1.

Condition-related causes

Poor adherence causes a pervasive problem across most clinical conditions, despite the potentially serious sequelae. Moreover, certain diseases cause physical, psychological and cognitive problems that potentially promote unintentionally poor adherence. A comprehensive literature review showed that the average number of patients showing medication possession ratios in excess of 80% during a 12-month follow-up was 64% for antihypertensives, 58% for oral hypoglycemic agents, 51% for lipid-lowering agents and 69% among those taking multiple treatments. Overall, 63% of patients persisted with treatment for 12 months; the proportion of patients who persisted was similar across the therapeutic classesCitation12.

Diabetes

Adherence to diabetes therapy varies greatly, with rates reported from 36% to 93% for oral antihyperglycemic agents for treatment of type 2 diabetes; adherence rates tend to be higher with monotherapy. For insulin use, adherence rates range from 73% to 86%, with adolescents significantly more likely to be poorly adherentCitation36.

Multiple sclerosis

Non-adherence is relatively common in people with MS. For example, only between 60% and 76% of patients adhere to interferon-beta and glatiramer acetate during follow-up lasting 2 to 5 yearsCitation37. Barriers which commonly contribute to non-adherence associated with MS focus mainly on difficulties with injections, a perceived lack of efficacy of the treatment and adverse events related to disease-modifying therapies such as the interferon betas, including flu-like symptoms, depression and injection site reactions. Complacency towards a therapy which seems to have no effect may be a problem when a patient is in remission, as is treatment fatigueCitation38. Building a strong relationship between patient and healthcare provider is important in a chronic neurologic disease such as MSCitation37; a poor relationship can contribute to poor adherenceCitation21. Injection anxiety and poor injection technique, which can make administration more painful, further undermine adherence among people with MSCitation51.

Growth hormone deficiency

Pain at the site of injection contributes to reduced adherence in administration of r-hGHCitation39. Poor adherence may therefore stem from a lack of understanding on the part of the patient of the possible implications for not taking their treatment as prescribedCitation39.

Asthma

A third of adults with asthma in UK general practice admit poor adherenceCitation48. In a study of 117 patients aged 65 to 102 years with chronic asthma, only 9% (assessed using the Modified Morisky Scale and 21% using Visual Analogue Scale [VAS]) showed high adherence to therapy.

Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular disease is now the leading cause of mortality in the developing world and tends to strike those in their most economically productive working yearsCitation52. Nevertheless, adherence with medicines to treat and prevent cardiovascular disease is often poor in both the developed and developing world.

HIV/AIDS

In a study from South Africa, 37.5% of patients attending a rural health center were non-adherent with antiretroviral therapy. Poor adherence was particularly common in those who were single (48.9% and 36.5% in men and women, respectively), with tertiary education (60% men only), in those who consumed alcohol regularly (47.1% and 60.7% in men and women, respectively) and in those who were unemployed (56.1% men only). Common reasons for missing doses were being away from home (57.1%), simply forgot (41.3%), side effects (50.8%) and being too busy (49.2%)Citation53.

Phenylketonuria

Phenylketonuria (PKU) is a rare, inherited disorder caused by mutations in the gene that encodes the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH), leading to impairment or negation of the enzyme’s activity in metabolism of the amino acid phenylalanine. If left untreated from birth, levels of phenylalanine and its metabolites in blood and tissues rise to toxic levels and lead to severe mental retardation, seizures, severe behavioral difficulties and other outcomes. The estimated prevalence across Europe is one case of PKU per 10,000 live birthsCitation54. Diagnosis of PKU is by neonatal screening of blood samples, with treatment by implementation of a strict phenylalanine-restricted diet from early in lifeCitation55,Citation56. In one study, only 10 of 25 adults with PKU had continuously adhered to the diet, while seven discontinued before the age of 5 yearsCitation57. However, strict adherence with this highly restrictive diet is essential to prevent or minimize the effects of PKU.

Patient-related causes

Patients may fail to adhere adequately either deliberately or accidentally. Multiple factors have been identified that are associated with an increased risk of poor adherence, including psychological problems and cognitive impairment, a complex treatment regimen, presence of side-effects of treatment, a lack of insight into disease and belief in treatment, poor relationship between provider and patient, poor information provided to the patient, missed appointments and high costs of treatment.

Additionally, a patient who is fully compliant to treatment may still exhibit a poor response, due to inadequate storage or poor administration. For a number of treatments the method and time of administration is important to achieve sufficient results; for example, the presence of food within the gastrointestinal tract has been shown to impact the absorption of drugsCitation58, therefore it is important that instructions regarding the administration of a medication with or without food are followed precisely to ensure optimum efficacy. Furthermore, the incorrect storage of a drug can reduce its efficacy; treatments requiring reconstitution, for example, often need to be kept refrigerated following the reconstitution process in order to avoid a poor responseCitation59,Citation60.

Interventions to improve adherence

Despite the difficulties in measuring adherence accurately and quantifying any changes in patients’ behavior, several approaches to improving adherence have been assessed in clinical trials. While these are discussed later, improving adherence usually depends on implementing several strategies to address the causes of poor adherence in each patient. Interventions are summarized in .

Social and economic interventions

There are several ways to address poor adherence caused by socioeconomic factors. Healthcare professionals could, for example, address illiteracy or poor educational attainment by offering careful explanations tailored to the patients’ level of education. A medical social worker could help the patients or their families to access social security, housing and other benefits, while a medical anthropologist could suggest interventions that work in harmony with prevailing cultural, social and religious attitudes and realitiesCitation41. Patient groups may be able to help improve knowledge and address social isolation, especially if the condition is relatively rare. However, further studies need to quantify the costs and consequences associated with such issues to help clinics determine the appropriate level of investment in each of these areas.

Healthcare team and health system interventions

Relationships between healthcare professionals and patients/carers that are based on mutual trust facilitate communication and engender confidence in the professional’s recommendations. This should, in turn, improve adherenceCitation44. There are several reasons why a poor patient–physician relationship may develop, including short consultations and poor communicationCitation61. It is important that healthcare professionals receive high-quality training which allows them to educate and consult patients effectively about diseases and available treatments; a patient survey in people with Parkinson’s disease has shown that the delivery of a diagnosis can have a significant impact on their quality of lifeCitation62, which supports the need for good communication between physicians and their patients.

A meta-analysis of 48 published studies found a statistically significant (weighted mean effect size = 0.145) correlation between improved physician/patient collaboration and better adherence. Importantly, this relationship remained valid in numerous settings including pediatric and adult patients, chronic and acute conditions, and in primary and specialist care. The authors concluded that including “the patient’s perspective during the consultation is essential to obtaining cooperation once the patient has left the physician’s office”. They add that “physicians need to be encouraged to promote collaboration within every medical consultation”Citation63.

It is important to remember that physicians are often part of a multidisciplinary team; this can involve pharmacists, nurse practitioners, and specific therapists, depending on the relevant condition. Encouraging the patient to communicate and cooperate efficiently with all members of the multidisciplinary team can help to improve adherence; fully involving a patient in treatment and therapy decisions could help to improve their understanding of the diseaseCitation1, ultimately leading to improved management of their conditionCitation64.

Education regarding the importance of good adherence needs to begin with the patient’s first visit to the clinic. One study examined adherence with drugs for asthma, diabetes, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, breast cancer, glaucoma or osteoporosis in medication-naïve and experienced patients. Discontinuation rates during the first 30 days among medication-naïve patients were 17.4% to 42.6% higher compared with the medication-experienced group. Median times to discontinuation were 14.2% to 28.9% longer among medication-experienced patientsCitation42. In some cases, the pattern for adherence could be established early in the course of treatmentCitation20.

Healthcare systems could also adopt procedures to remind patients to attend their clinic appointments. Patients who miss clinic appointments may also experience difficulties adhering to other aspects of treatment as well as missing the regular reinforcement that helps to counter therapeutic fatigue. In a study of people with diabetes, each 10% increase in the rate of missed appointments decreased the odds of good control by 12% and increased the likelihood of poor control by 24%Citation43. In a retrospective evaluation of patients attending a US diabetes clinic over 10 years after their initial presentation, HbA1c declined by 0.12% for every intervening appointmentCitation7. Clinics should encourage their patients with diabetes to not miss their appointments, which may mean adapting conventional systems to maximize the opportunity for patients to attend. For example, clinic attendance rates among young adults with type 1 diabetes are higher in centers that offer evening appointments and remind patients by letter or telephone than in clinics with more conventional opening hours and that did not proactively remind patients of appointmentsCitation65. Furthermore, regular, frequent contact between providers and patients by telephone promoted regimen adherence and improved glycemic controlCitation66. Further studies need to quantify the relative cost-effectiveness of such initiatives.

Studies have shown that community pharmacists can help improve patient adherence by identifying potential non-adherence amongst patients and implementing solutionsCitation67. Intervention by a community pharmacist has also shown to improve patient adherence, as well as patient satisfactionCitation68. A pilot program conducted by the California Department of Health Care Services and Medi-Cal in community pharmacies showed that medication therapy management services (e.g. offering appointments to discuss therapy, offering personalized packaging, finding a peer sponsor, regular telephone calls, etc.) improved adherence in patients with HIV/AIDSCitation69,Citation70.

Access and affordability to healthcare is also relevant for adherence. There is some data to show that co-pay reduction programs (where the contribution that an insured patient is required to make to the cost of their medication costs is reduced or removed), may improve adherence in some chronic diseaseCitation71. The supply of pharmaceutical samples may also serve to improve adherence in some patients. This can encourage patient choice and ensures that the treatment is initiated in front of the physician or pharmacist, resulting in better understanding of the medicationCitation72. Treatments for chronic diseases such as HIV/AIDS can be very expensive, and patients may not be able to afford their prescription. Drug assistance programs devised by pharmaceutical companies and charitable associations have been shown to reduce direct medical costs of treatment effectively, which may improve adherenceCitation73,Citation74.

Therapy-related interventions

Since many diseases, including the early stages of MS, hypertension and type 2 diabetes, are generally asymptomatic, at least before complications emerge, adherence does not improve subjective well-being.

A US study that enrolled elderly, community-dwelling adults found that resolution of the disease and a change in the prescription accounted for 37.4% and 15.8% of wasted prescribed medicines, respectively. However, patient-perceived ineffectiveness and patient-perceived adverse effects accounted for 22.6% and 14.4% of the wastage, respectivelyCitation75. Therefore, patients need to appreciate that the benefits of treatments outweigh the disadvantages of adverse events and the other costsCitation45. Increased treatment complexity may also make poor adherence more likely. For example, a systematic review of 20 studies found that all trials reported higher adherence rates (based on electronic monitoring) with low dosing frequency regimens. The differences reached statistical significance in 75% of studies. Overall, patients receiving once-daily regimens were adherent on 22% to 41% more days than those taking medication three times a day and on 2% to 44% more days than those using twice-daily regimensCitation46.

Condition-related interventions

A number of conditions frequently related to poor adherence, such as MSCitation38, can often be the cause due to an increased risk of depression or lack of cognitive function, etc. Therefore, healthcare providers should remain vigilant for, and when appropriate manage, co-morbidities, such as depression, anxiety and drug and alcohol abuse that are associated with poor adherenceCitation1.

Unfortunately, many physicians may feel poorly able to adequately manage the psychological sequelae associated with chronic diseases. In the Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) study, only 42% of healthcare providers felt able to identify, evaluate and manage the psychological needs of patients suffering from diabetesCitation76. This emphasizes the need for adequate and appropriate training of healthcare professionals.

Several strategies have improved adherence in a variety of therapy areas, although few have been subject to rigorous pharmacoeconomic evaluations. The following examples illustrate some of these approaches.

Diabetes

Some patients with diabetes find that maintaining blood glucose control and the progression of the disease despite their efforts can engender feelings of helplessness and frustration. A psychological approach called Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) teaches patients to cope with thoughts and emotions that hinder attainment of goals. Counseling using ACT can improve glycemic control, lowering mean HbA1c over 3 months follow-up from 8.17% to 7.47% in patients and increasing the proportion of patients who attained target glycemic control (HbA1c < 7.0%) from 11 of 43 to 21 of 43Citation47.

Electronic monitoring can also help identify opportunities to intervene to improve adherence and motivate patients to take their medicine. Prospective studies using electronic monitoring suggest that patients with diabetes took between 67% and 85% of doses of oral hypoglycemic agents as prescribed. Electronic monitoring identified poor compliers and the subsequent use of interventions improved adherence by between 61% and 79%. Monitoring suggested that elevated glucose or HbA1c levels were related to missed doses and not under-prescribingCitation36.

Multiple sclerosis

Increased risk of disease-related conditions such as depression can result in higher levels of poor adherence in MS therapy; discussion of the expected effects of a therapy with the patient can help with their managementCitation37. While good patient education can help to address this poor adherence in MS, innovations in delivery technology can reduce needle anxiety and facilitate administration by, for example, hiding the needle, facilitating correct technique, being suitable for use at several injection sites, and, overall, improving patient satisfaction. Many patients with MS find that auto-injector devices can reduce the incidence of injection-site reactions and discomfortCitation77.

Growth hormone deficiency

The main cause of poor adherence in growth hormone therapy is the pain caused when the treatment is administered; when surveyed on important features of an r-hGH injection device, a group of 67 individuals with experience in administration of r-hGH injections considered lack of pain during injection to be the third most important feature (of 19)Citation78. Also, a device with an automatic needle insertion system has been associated with less pain than an injection device with manual needle insertionCitation79, a feature which may help to improve adherence.

Growth hormone deficiency is regarded as a ‘silent disease’; that is, it lacks any obvious symptoms of poor health, apart from short stature. To address this issue, patient and caregiver education would be an appropriate course of action, to explain the condition and the importance of therapyCitation21,Citation44. Monitoring of adherence can lead to early identification of low responders, allowing optimization of r-hGH dose to achieve maximum clinical benefitCitation80.

Asthma

Several factors increase the risk of poor control among patients using inhaled corticosteroids, including being overweight, having chronic cough and phlegm and sensitization to CladosporiumCitation40. Rhinitis (odds ratio: 4.62) and smoking (odds ratio: 4.33) also predict poor control. Increasing rhinitis severity and a greater number of cigarettes smoked each day were associated with deteriorating asthma control. Indeed, these factors were more influential in determining poor control than adherence to inhaled corticosteroids (odds ratio: 1.35)Citation48. Therefore, interventions that treat rhinitis and encourage smoking cessation should improve control and, by augmenting the benefits of treatments, improve adherence. Several smoking cessation interventions are cost-effective in a variety of settingsCitation81,Citation82.

Cardiovascular disease

Even though cardiovascular disease is globally known as the leading cause of mortality in the developing world, poor adherence to medication is still remarkably high; in the USA, for example, only 51% of patients adhere to antihypertensive regimens. Chapman and colleaguesCitation50 performed a literature search and standardized results over 6 months to compare the relative effectiveness and costs of interventions that aim to improve adherence with antihypertensives and lipid-lowering medication. The various interventions produced relative improvements (RI) ranging from 1.11 (mailed reminder to refill the scrip) to 4.65 (management by a community pharmacist). Six-month costs varied from $9.59 with mailed reminders to $142.22 per patient for a strategy that comprised increased pharmacy care, patient diaries and educational material. In the absence of formal comparative prospective studies, there is a need to apply a similar methodology to other drugs and settings.

HIV/AIDS

In HIV/AIDS, as with many other therapeutic areas, there is no single definitive measure for assessment of adherence to therapy or tool to improve poor adherenceCitation83. It has been recommended that, prior to initiation of therapy, the patient should be fully assessed and an individualized treatment plan agreed. Successful intervention strategies to improve adherence include support groups, peer counselors and educators, cognitive-behavioral and reminder strategies and healthcare team membersCitation84.

In a 6-month randomized controlled trial conducted in the USA, patients voluntarily treated by directly administered antiretroviral therapy (DAART) showed a significantly greater improvement in health outcomes than those whose therapy was self-administered, and DAART has been shown to be a reliable and effective means of ensuring adherenceCitation85. However, the high number of people infected with HIV, intensity of workload and complexity of programming mean that DAART may be impractical for day-to-day application. Modified directly observed therapy (mDOT), a regimen under which only a portion of total doses of antiretroviral medication are administered under supervision, has been shown to be feasible and adaptable. Although empirical data are required to support decisions around the design of mDOT programs, a key factor seems to be the flexibility of such programs and the importance of accommodating the specific requirements of the target populationCitation86. Such insights suggest potential points of intervention for initiatives to improve adherence, although the cost-effectiveness, in resource-poor as well as developed nations, awaits clarification.

Phenylketonuria

While it is widely accepted that neonatal diagnosis and early treatment of PKU is of great importance, due to the variability and age of many economic analyses of screening and treatment, the actual financial impact of therapy is unclear. However, an economic modeling study conducted in the UK concluded that neonatal screening for PKU is financially worthwhile. The model indicated that, in the UK, a direct net benefit of £93,400 per case detected and treated could be gained; in countries with a lower incidence of PKU than the UK (70 cases annually) and/or lower costs of caring for the handicapped, screening may not be cost-saving, but it may still be cost effectiveCitation87.

Recently, some new treatments for PKU, beyond the traditional dietary restrictions, have been investigated, including phenylalanine-free dietary supplements with improved flavors, supplementation of large neutral amino acids to compete for blood–brain barrier carriers, augmentation of alternative degradation pathways (phenylalanine ammonia-lyase therapy) and increase in PAH activity by supplementation of tetrahydrobiopterinCitation88. The latter may be addressed by the growing body of evidence indicating that the oral medication sapropterin dihydrochloride is effective in reducing phenylalanine levels in a substantial proportion of PKU patients as an adjunct to the low-phenylalanine diet. Treatment with sapropterin can reduce phenylalanine levels and ease the dietary burden, with the potential to improve adherence to the diet; however, current data are supportive only of short courses of treatment and further randomized controlled trials will be necessary to establish long-term efficacy and safety and cost-effectivenessCitation89,Citation90.

Patient-related interventions

When poor adherence occurs unintentionally, adherence aids such as Dosette boxes, calendar packs and reminders can help to improve adherence rates. Addressing inappropriate beliefs about the disease, patient education on pathology and the importance of treatment, as well as periodic monitoring and reinforcement, can help overcome intentional and unintentional poor adherenceCitation34. Awareness and identification of such factors may allow healthcare professionals to intervene to improve adherence, although even patients who do not exhibit these characteristics may miss dosesCitation21.

Who pays for interventions that improve adherence?

Despite the growing body of evidence that several interventions can improve adherence in a variety of settings and clinical indications, some bodies reimbursing healthcare costs do not acknowledge the importance of adherence in their payment schedules. For example, in certain conditions improved adherence and, therefore, outcomes can produce gains for society (e.g. reduced disability or improved productivity), but could increase the financial burden on hospitals and payers (e.g. higher treatment costs or longer consultations with healthcare professions). Improved adherence also enhances psychosocial outcomes, which reduces indirect costs such as reduced productivity. Therefore, while society may gain financially from improved adherence, certain interventions in some conditions could increase direct expenditure. Hospitals and payers may not feel financially motivated to implement improvements that do not also markedly reduce direct costs, especially in the face of competing priorities that may have a greater impact on their budgets. Therefore, including adherence in reimbursement agreements may incentivize healthcare providers to address poor adherence.

Governments and policy makers can also play a role. In the USA for example, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 recognizes medication adherence and medication therapy management as areas that should receive funding. Initiatives where governments could play a role in improving adherence might include collaborating with the pharmaceutical industry to support health awareness campaigns on how to gain most benefit from prescribed medicines. Governments could also ensure there are policies and resources in place to ensure adequate training of healthcare professionals in the appropriate communication skills to use when dealing with individual patients and advising them of simple interventions to improve adherence. Supporting greater research into adherence could also be beneficial. The Medical Outcomes Study examined resource utilization and patient care within the different US health systems and with different physician specialists, and highlighted where there were inconsistenciesCitation91. Further studies examining variations in adherence in such settings might uncover areas requiring particular attention. As a result, funds could be allocated to the areas that would gain the most benefit from an adherence program. There would be an increase in immediate expenditure but it would be the more cost-effective option in the long term.

Patient groups and payers help develop ‘high level’ healthcare strategies, but adherence is rarely on their agenda. Increasingly, policy makers, purchasers and providers use pharmacoeconomic research to predict the clinical and economic impact of improving adherence with existing interventions against introducing a new medical technology. Including non-adherence more systematically in pharmacoeconomic considerations than is often the case at present would facilitate decision making.

Currently, most clinical trials demonstrate efficacy rather than investigating effectiveness outcomes, such as the costs and consequences associated with non-adherence. Furthermore, studies often have major flaws in their economic methodology, especially in terms of incremental and sensitivity analysis, while follow-up may be inadequate to assess cost-effectiveness accurately or ascertain whether adherence interventions produce cost offsets from the perspective of individual providers. Such flaws limit the value of these studies when healthcare services need to determine whether to introduce a particular drug or innovation. Until such studies become standard, economic modeling could present a viable alternative to costly studies.

Finally, it is worth noting that the increasing importance of quota registers in some countries makes it difficult to budget for adherence programs. Imposing quotas of patients that clinicians should manage for a relatively low, fixed fee can hinder attempts to allocate a budget for programs that aim to improve adherence. Once again, including adherence in reimbursement agreements may incentivize healthcare providers to address poor compliance.

Conclusions

The clinical and economic consequences of non-adherence and interventions to improve compliance reflect the nature and severity of non-adherence, as well as the pathophysiology and severity of the disease. Interventions that aim to improve adherence may confer cost-effectiveness benefits in some indications and settings. However, there is a pressing need for rigorous trials. Current studies often have major flaws in economic methodology, especially in terms of incremental analysis and sensitivity analysis. Economic modeling could present a viable alternative to costly clinical studies. Nevertheless, while considerable uncertainty remains about the extent of the improvement, good adherence can help payers and providers contain costs by extracting maximum value from their investment into therapies. Educating payers and providers to recognize the benefits remains a challenge.

Declaration of interest

A.G. declares that he has no relevant competing interests.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The preparation of this manuscript was funded by Merck Serono International SA (an affiliate of Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

Acknowledgements

Editorial assistance for development of this manuscript was provided by Mark Greener of PHASE II International (Esher, Surrey, UK). The author had full control over the content of the manuscript and takes sole responsibility for the final version submitted.

Notes

* MEMS is a registered trademark of AARDEX, USA.

† Smartinhaler is a registered trademark of Nexus6 Ltd, USA.

‡ Doser is a registered trademark of Meditrack Products, USA.

§ easypod is a registered trademark of Merck Serono SA, Switzerland.

¶ RebiSmart is a registered trademark of Merck Serono SA, Switzerland.

References

- World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003

- Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008;11:44-7

- Aronson JK. Editors’ view: compliance, concordance, adherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2007;63:383-4

- Haynes RB, Ackloo E, Sahota N, et al. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008(2):CD000011

- Heisler M, Faul JD, Hayward RA, et al. Mechanisms for racial and ethnic disparities in glycemic control in middle-aged and older Americans in the health and retirement study. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1853-60

- Schectman JM, Nadkarni MM, Voss JD. The association between diabetes metabolic control and drug adherence in an indigent population. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1015-21

- Rhee MK, Slocum W, Ziemer DC, et al. Patient adherence improves glycemic control. Diabetes Educ 2005;31:240-50

- Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA, et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 2000;321:405-12

- The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes 1995;44:968-83 retinopathy in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes 1995;44:968-83

- Beckles GL, Engelgau MM, Narayan KM, et al. Population-based assessment of the level of care among adults with diabetes in the U.S. Diabetes Care 1998;21:1432-8

- Diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance. In: Sicree R, Shaw J, Zimmet P (eds) IDF Diabetes Atlas, 4th Edn. 2009. Available at: http://www.diabetesatlas.org/content/background-papers-pdf [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- Cramer JA, Benedict A, Muszbek N, et al. The significance of compliance and persistence in the treatment of diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia: a review. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:76-87

- Yang Y, Thumula V, Pace PF, et al. Predictors of medication nonadherence among patients with diabetes in Medicare Part D programs: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Ther 2009;31:2178-88

- Yeaw J, Benner JS, Walt JG, et al. Comparing adherence and persistence across 6 chronic medication classes. J Manag Care Pharm 2009;15:728-40

- Bailey CJ, Kodack M. Patient adherence to medication requirements for therapy of type 2 diabetes. Int J Clin Pract 2011;65:314-22

- Shetty S, Secnik K, Oglesby A. Relationship of glycemic control to total diabetes-related costs for managed care health plan members with type 2 diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm 2005;11:559-64

- Berger J. Economic and clinical impact of innovative pharmacy benefit designs in the management of diabetes pharmacotherapy. Am J Manag Care 2007;13(Suppl 2):S55-8

- Sokol MC, McGuigan KA, Verbrugge RR, et al. Impact of medication adherence on hospitalization risk and healthcare cost. Med Care 2005;43:521-30

- Freedberg KA, Hirschhorn LR, Schackman BR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an intervention to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;43(Suppl 1):S113-18

- Norgren S. Adherence remains a challenge for patients receiving growth hormone therapy. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2009;6(Suppl 4):545-8

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487-97

- Electronic monitoring of adherence. AARDEX. Sion, Switzerland. Available at: http://www.aardexgroup.com/aardex_index.php?group=aardex&id=83 [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- Peer reviewed publications. AARDEX. Sion, Switzerland. Available at: http://www.iadherence.org/publication.action [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- Smartinhalers. Nexus6. Franklin, OH, USA. Available at: http://www.smartinhaler.com/Researcher_SI.aspx [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- What is the Doser? Meditrack. Easton, MA, USA. Available at: http://www.doser.com/dWhat.html [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- Dahlgren J, Veimo D, Johansson L, et al. Patient acceptance of a novel electronic auto-injector device to administer recombinant human growth hormone: results from an open-label, user survey of everyday use. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:1649-55

- Devonshire V, Arbizu T, Borre B, et al. Patient-rated suitability of a novel electronic device for self-injection of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in relapsing multiple sclerosis: an international, single-arm, multicentre, Phase IIIb study. BMC Neurology 2010;10:28

- Hanaire H, Lassman-Vague V, Jeandidier N, et al. Treatment of diabetes mellitus using an external insulin pump: the state of the art. Diab Metab 2008;34:401-23

- Product information. Medtronic. Northridge, CA, USA. Available at: http://www.minimed.com/products/index.html [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- DANA Diabecare R. SOOIL. Seoul, Korea. Available at: http://www.sooil.com/NEW/eng/m3_r_01.html [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- Accu-Chek Combo System. Roche. Basel, Switzerland. Available at: http://www.accu-chek.co.uk/gb/products/insulinpumps/combo.html [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- See how we match up to competition. Animas. West Chester, PA, USA. Available at: http://www.animas.com/animas-insulin-pumps/onetouch-ping [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- Omnipod system overview. Insulet. Bedford, MA, USA. Available at: http://www.myomnipod.com/about-omnipod/system-overview/ [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- George J, Kong DC, Stewart K. Adherence to disease management programs in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2007;2:253-62

- Jentzsch NS, Camargos PA, Colosimo EA, et al. Monitoring adherence to beclomethasone in asthmatic children and adolescents through four different methods. Allergy 2009;64:1458-62

- Cramer JA. A systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetes. Diabetes Care 2004;27:1218-24

- Costello K, Kennedy P, Scanzillo J. Recognizing nonadherence in patients with multiple sclerosis and maintaining treatment adherence in the long term. Medscape J Med 2008;10:225

- Patti F. Optimizing the benefit of multiple sclerosis therapy: the importance of treatment adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence 2010;4:1-9

- Haverkamp F, Johansson L, Dumas H, et al. Observations of nonadherence to recombinant human growth hormone therapy in clinical practice. Clin Ther 2008;30:307-16

- Cazzoletti L, Marcon A, Janson C, et al. Asthma control in Europe: a real-world evaluation based on an international population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:1360-7

- Ware NC, Idoko J, Kaaya S, et al. Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: an ethnographic study. PLoS Med 2009;6:e11

- Vanelli M, Pedan A, Liu N, et al. The role of patient inexperience in medication discontinuation: a retrospective analysis of medication nonpersistence in seven chronic illnesses. Clin Ther 2009;31:2628-52

- Schectman JM, Schorling JB, Voss JD. Appointment adherence and disparities in outcomes among patients with diabetes. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:1685-7

- Gold DT, McClung B. Approaches to patient education: emphasizing the long-term value of compliance and persistence. Am J Med 2006;119(4 Suppl 1):S32-7

- Delamater AM. Improving patient adherence. Clinical Diabetes 2006:24;71-7

- Saini SD, Schoenfeld P, Kaulback K, et al. Effect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseases. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:e22-e33

- Gregg JA, Callaghan GM, Hayes SC, et al. Improving diabetes self-management through acceptance, mindfulness, and values: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2007;75:336-43

- Clatworthy J, Price D, Ryan D, et al. The value of self-report assessment of adherence, rhinitis and smoking in relation to asthma control. Prim Care Respir J 2009;18:300-5

- Bozek A, Jarzab J. Adherence to asthma therapy in elderly patients. J Asthma 2010;47:162-5

- Chapman RH, Ferrufino CP, Kowal SL, et al. The cost and effectiveness of adherence-improving interventions for antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drugs. Int J Clin Pract 2010;64:169-81

- Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Likosky W, et al. Injectable medication for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: the influence of self-efficacy expectations and injection anxiety on adherence and ability to self-inject. Ann Behav Med 2001;23:125-32

- Gaziano TA. Reducing the growing burden of cardiovascular disease in the developing world. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:13-24

- Bhat VG, Ramburuth M, Singh M, et al. Factors associated with poor adherence to anti-retroviral therapy in patients attending a rural health centre in South Africa. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2010;29:947-53

- Blau N, van Spronsen FJ, Levy HL. Phenylketonuria. Lancet 2010;376:1417-27

- National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Panel. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: phenylketonuria: screening and management, October 16–18, 2000. Pediatrics 2000;108:972-82

- Management of PKU. April 2004. The National Society for Phenylketonuria (United Kingdom) Limited. Available at: http://www.nspku.org/Documents/Management%20of%20PKU.pdf [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- Ris MD, Williams SE, Hunt MM, et al. Early-treated phenylketonuria: adult neuropsychologic outcome. J Pediatr 1994;124:388-92

- Charman WN, Porter CJH, Mithani S, et al. Physicochemical and physiological mechanisms for the effects of food on drug absorption: the role of lipids and pH. J Pharmaceut Sci 1997;86(3):269-82

- Yuen KCJ, Amin R. Developments in administration of growth hormone treatment: focus on Norditropin® Flexpro®. Patient Pref Adhere 2011;5:117-24

- Ziance R, Chandler C, Bishara RH. Integration of temperature-controlled requirement into pharmacy practice. J Am Pharm Assoc 2009;49:e61-e69

- Morgan M. The doctor–patient relationship. In: Sociology as Applied to Medicine, 6th Edn. WB Saunders Company Limited, Philadelphia, USA, 2008

- Global Parkinson’s Disease Survey Steering Committee. Factors impacting on quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: results from an international survey. Mov Disord 2002;17:60-7

- Arbuthnott A, Sharpe D. The effect of physician–patient collaboration on patient adherence in non-psychiatric medicine. Patient Educ Couns 2009;77:60-7

- Kulkarni AS, Balkrishnan R, Anderson RT, et al. Medication adherence and associated outcomes in Medicare health maintenance organization-enrolled older adults with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2008;23:359-65

- Wills CJ, Scott A, Swift PG, et al. Retrospective review of care and outcomes in young adults with type 1 diabetes. BMJ 2003;327:260-1

- Aubert RE, Herman WH, Waters J, et al. Nurse case management to improve glycemic control in diabetic patients in a health maintenance organization: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:605-12

- Raynor DK, Nicolson M, Nunney J, et al. The development and evaluation of an extended adherence support programme by community pharmacists for elderly patients at home. Int J Pharmacy Pract 2000;8:157-64

- Blenkinsopp A, Phelan M, Bourne J, Dakhil N. Extended adherence support by community pharmacists for patients with hypertension: a randomised controlled trial. Int J Pharmacy Pract 2000;8:165-75

- Hirsch JD, Gonzales M, Rosenquist A, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence, medication use, and health care costs during 3 years of a community pharmacy medication therapy management program for Medi-Cal beneficiaries with HIV/AIDS. J Manag Care Pharm 2011;17:213-23

- Rosenquist A, Best BM, Miller TA, et al. Medication therapy management services in community pharmacy: a pilot programme in HIV specialty pharmacies. J Eval Clin Pract 2010;16:1142-6

- Chernew ME, Shah MR, Wegh A, et al. Impact of decreasing copayments on medication adherence within a disease management environment. Health Affairs 2008;27:103-12

- Alikhan A, Sockolov M, Brodell RT, et al. Drug samples in dermatology: special considerations and recommendations for the future. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;62:1053-61

- Johri M, David Paltiel A, Goldie SJ, et al. State AIDS Drug Assistance Programs: equity and efficiency in an era of rapidly changing treatment standards. Med Care 2002;40:429-41

- Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Freedberg KA. AIDS Drug Assistance Programs: highlighting inequities in human immunodeficiency virus-infection health care in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:606-10

- Morgan TM. The economic impact of wasted prescription medication in an outpatient population of older adults. J Fam Pract 2001;50:779-81

- Peyrot M, Rubin RR, Lauritzen T, et al. Psychosocial problems and barriers to improved diabetes management: results of the Cross-National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) Study. Diabet Med 2005;22:1379-85

- Lugaresi A. Addressing the need for increased adherence to multiple sclerosis therapy: can delivery technology enhance patient motivation? Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2009;6:995-1002

- Dumas H, Panayiotopoulos P, Parker D, et al. Understanding and meeting the needs of those using growth hormone injection devices. BMC Endocr Disord 2006;6:5

- Main KM, Jørgensen JT, Hertel NT, et al. Automatic needle insertion diminishes pain during growth hormone injection. Acta Paediatr 1995;84:331-4

- Chatelain P, Latour S, Maetzel A. The economic value of the easypod® electronic auto injector in improving the response to growth hormone (GH) in children with idiopathic growth hormone deficiency (IGHD): a cost-consequence analysis. Poster presentation at ISPOR 13th European Congress, 6–9 November 2010, Prague, Czech Republic. Abstract available at: http://www.ispor.org/RESEARCH_STUDY_DIGEST/details.asp [Last accessed 1 April 2011]

- Ruger JP, Weinstein MC, Hammond SK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of motivational interviewing for smoking cessation and relapse prevention among low-income pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Value Health 2008;11:191-8

- Gordon L, Graves N, Hawkes A, et al. A review of the cost-effectiveness of face-to-face behavioural interventions for smoking, physical activity, diet and alcohol. Chronic Illn 2007;3:101-29

- Chesney A. The elusive gold standard. Future perspectives for HIV adherence assessment and intervention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2006;43(Suppl 1):S149-55

- Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services. January 10, 2011; 1-166. Available at: http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf [Last accessed 31 March 2011]

- Altice FL, Maru DS, Bruce RD, et al. Superiority of directly administered antiretroviral therapy over self-administered therapy among HIV-infected drug users: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:770-8

- Goggin K, Liston RJ, Mitty JA. Modified directly observed therapy for antiretroviral therapy: a primer from the field. Public Health Reports 2007;122:472-81

- Lord J, Thomason MJ, Littlejohns P, et al. Secondary analysis of economic data: a review of cost-benefit studies of neonatal screening for phenylketonuria. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999;53:179-86

- Santos LL, Magalhães MC, Januário JN, et al. The time has come: a new scene for PKU treatment. Genet Mol Res 2006;5:33-44

- Blau N, Bélanger-Quintana A, Demirkol M, et al. Management of phenylketonuria in Europe: survey results from 19 countries. Mol Genet Metab 2010;99:109-15

- Somaraju UR, Merrin M. Sapropterin dihydrochloride for phenylketonuria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;6:CD008005

- Tarlov AR, Ware JE Jr, Greenfield S, et al. The medical outcomes study. An application of methods for monitoring the results of medical care. J Am Med Assoc 1989;262:925-30