Abstract

Objective:

The relationship between chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) control and pain medication (analgesic) adherence has not been widely documented. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between pain intensity and the degree of adherence to analgesic medication prescribed in pain clinics. There was also a special emphasis on the influence of polypharmacy on adherence.

Methods:

A cross-sectional clinical survey was carried out in pain clinics across Spain. Demographic and clinical data were collected from patients: pain intensity, analgesic prescription and adherence, and the presence of concomitant medical conditions and treatments. The relationship between analgesic adherence and pain intensity was analyzed using correlations and propensity scores based on ordinal logistic regression. Correlates of pain intensity were explored using multiple linear regression.

Results:

Data was gathered from 1407 patients; 1321 were eligible for analysis. Their mean (standard deviation) age was 61.6 (14.7) years and the majority (67.3%) were women. More than half (57.9%) received step 3 analgesics. Pain intensity was scored 5 out of 10 on average. Just 65.9% of patients were reported to not have missed any analgesic dose during the previous week. Pain intensity correlated negatively with analgesic adherence (rs = −0.151, p < 0.001). Moderate versus very intense pain was predicted in patients with ‘good’ and ‘very poor’ adherence, respectively. The presence of concomitant medications also correlated negatively with analgesic adherence (rs = −0.074, p = 0.007). However, few investigators reported such a negative effect of polypharmacy.

Limitations:

Key limitations of this research are its cross-sectional design and the absence of an objective means of measuring medication adherence.

Conclusions:

This study has shown that there is a small but significant inverse relationship between analgesic adherence and CNCP control, which has remained elusive to date and should be further evaluated. Polypharmacy also had a negative influence on adherence, although this was not acknowledged by all investigators.

Introduction

Chronic noncancer pain (CNCP) constitutes a prevalent health care problem that poses relevant personal, social and economical burdensCitation1. It is also a condition that is difficult to treatCitation2. Frequently, patients present a comorbid psychopathology that further complicates the therapeutic approach and may constitute a source of frustration for physicians not specialized in pain managementCitation3. In spite of these difficulties, there has been less research dedicated to CNCP than to acute pain and cancer painCitation4, even though it differs fundamentally from both of these conditions.

A number of barriers to effective chronic pain management have been cited. These include patient-related and professional/physician-related barriersCitation5,Citation6. Pain management programs that are multidisciplinary, comprehensive and individualized have shown to be effective to trim physician-related barriersCitation7. However, patient-related barriers, and among these misuse in the form of nonadherence to prescribed pain medication, persist, with an uncertain impact over clinical outcomesCitation8,Citation9. Although nonadherence to prescribed medication is a common problem in most chronic medical conditionsCitation6, the experience gained from chronic cancer and noncancer pain management has shown that nonadherence to pain medication constitutes a more nuanced issueCitation10–12. Yet, the number of studies that have focused on the topic of medication nonadherence in CNCP populations to date is limitedCitation9.

The present article reports the results of a study aimed at evaluating the relationship between pain control and pain medication adherence in patients suffering from CNCP as well as the influence that polypharmacy (patients receiving several medications, for pain and other medical conditions) exerts on this relationship. The primary hypothesis was that there exists a relationship between pain control and pain medication adherence in patients with CNCP. This hypothesis has been discussed, but not proven, by prior research. The secondary aims were to describe the demographics and the clinical profiles of CNCP patients receiving care from pain specialists, and to describe the medication that they received.

Patients and methods

Design and patients

A cross-sectional clinical survey was done to collect information systematically from outpatients consulting pain clinics. During the first quarter of 2009, an invitation to contribute to this clinical survey was sent to all pain clinics operating within Spain. They were asked to collect a set of data from all eligible patients consenting to participate and meeting the selection criteria, observing the chronological order in which they attended their facilities. To respect the chronological order strictly, any pain specialist working at the pain clinics was able to gather the data, but each site was required to designate a coordinating investigator at that site to homogenize the criteria among contributing specialists. The recruitment target was set beforehand at 20 patients per site, although some sites were allowed to provide more cases on request if they had larger than average catchment areas. This chronological and capped recruitment procedure was intended to enhance sample representativeness, by limiting the influence of site-related factors over the chances of patients to reach the study, such as the availability or willingness of investigators to participate.

The target population consisted of all patients suffering from any CNCP condition within Spain. The source population of the study was a subset of the target population comprising patients who additionally received treatment in a pain clinic. Eligible patients were aged 18 years or more, received a diagnosis of CNCP more than 5 months ago, were on any pharmacologic treatment for pain (including adjuvant medications), received at least one prior consultation in the same pain clinic and provided consent for releasing their personal data for this research. Patients were excluded if they were unable to complete a pain scale or to attend an interview during the data collection.

The study was performed in accordance with the updated Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by an accredited Ethics Committee prior to the commencement date. All patients provided written informed consent in advance.

Assessment and procedures

Age, gender and the time elapsed since the patient was first seen at the pain clinic were recorded. The investigators were asked to specify the diagnoses associated with CNCP, and to classify them into one or more of the following categories: arthrosic/degenerative, inflammatory and radicular/neuropathic. Pain intensity, referred to the average of the preceding 4 weeks, was self-reported by patients on a numeric rating scale ranging from 0 to 10, with the following anchoring points: ‘very mild’ (0), ‘mild’ (1–2), ‘moderate’ (3–4), ‘intense’ (5–6), ‘very intense’ (7–8), ‘extreme’ (9) and ‘the worst imaginable intensity’ (10). Patients were asked how many times they missed a dose in the preceding week (none, 1 or 2, 3 to 5, 6 to 10, and more than 10 doses). Additionally, the investigators provided their subjective appraisal of patient’s adherence to pain medications since the last visit to the pain clinic using a Likert-type scale (very poor, poor, fair, good, very good). Five-category verbal rating scales (nothing, a bit, fair, much, very much) were used to record the investigator’s view on the impact of pain on the patient’s quality of life, daily activities, mood and sleep. A structured form was used to collect the patient’s complete medication scheme, including drugs given for conditions other than pain. Investigators were also asked whether the patient suffered from any chronic medical condition other than pain. Finally, they answered another Likert-type scale inquiring whether in their opinion the concomitant medications prescribed for these conditions affected patients’ adherence to pain medications (completely agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, completely disagree), and two further five-category verbal rating scales on how the presence of chronic medical conditions other than pain hindered the patient’s adherence to pain medications or disturbed the patient’s quality of life.

Data analysis

Observed data was used in all analyses; no imputation techniques were used for missing or incomplete data. Pain medications were categorized into the three steps of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) analgesic ladder for cancer painCitation13. Co-adjuvant drugs (atypical analgesics) were considered to be step 1 treatments. A fourth category was used for pain medications whose step could not be determined because of incomplete or incoherent data. Patients were distributed into the various steps according to the highest drug in their schemes (for example, a patient receiving only an antidepressant for pain was classified into step 1, while a patient receiving an antidepressant plus a strong opioid was classified into step 3). Patients’ diagnoses were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA), version 12.1. Medications with the WHO’s Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system, year 2010 version, considering the dose and the route of administration. Variables were described with appropriate statistics (as means, standard deviations, medians and interquartile ranges or as numbers and percentages).

To analyze the relationship between pain control and patient adherence to pain medications, several strategies were used. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated between the scores of the scales on pain intensity and on patients’ adherence (ordered from low to high intensity and from poor to good adherence, respectively). Spearman’s correlation coefficients were also calculated between the absence/presence of polypharmacy and the scores on patient adherence. The scores on pain intensity (0 to 10) were stratified by adherence level and their means compared by analysis of variance to detect any ascending pattern. Factors influencing pain intensity were explored by means of multiple linear regression, using the patient’s adherence level, gender, age and diagnostic category (arthrosic/degenerative, inflammatory and radicular/neuropathic), the step of pain medications, the number of drugs used to treat pain, the presence of chronic medical conditions other than pain and the presence of polypharmacy (medications unrelated to pain) as independent variables. The model was reduced by backward elimination based on the Wald’s t statistic. Finally, propensity scores of pain intensity for each adherence level were calculated using logistic regression. Modeling was done using the same set of independent variables described above.

The size of the sample was not formally calculated. However, for descriptive purposes, a recruitment target was set at 1000 patients to have a precision of ±3% for the estimation of a proportion of 50% with a confidence level of 95%. Additionally, this large sample size provides high power for statistical inferences. Sampling was done in conglomerates (the pain clinics) that were not selected randomly, because participation depended on the availability and willingness of participating physicians to collaborate. However, most of the units operative in Spain were involved.

Results

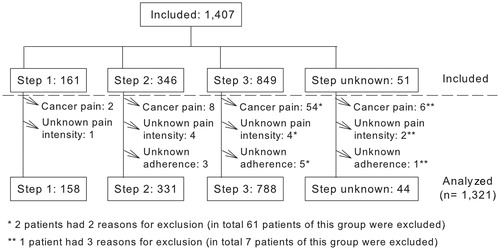

Data was gathered from 1407 patients by 126 pain specialists at 65 pain clinics (of a total of about 110 within Spain). At 49 sites the recruitment target of 20 patients was achieved. Another eight recruited fewer patients, the lowest number being nine patients at one of the sites, and a further eight sites included more than the target of patients (at one site there were 60 patients). Eighty-six patients were excluded because they had cancer pain or lacked essential data for the analysis, leaving a total of 1321 evaluable patients (). More than half (788 out of 1321, 59.7%) received step 3 analgesic drugs; 331 patients (25.1%) were on step 2 drugs at the most and 158 patients (12.0%) received only step 1 drugs. The step was unknown in 44 patients ().

describes the patients’ characteristics. Most of them (67.3%) were women and had an advanced age (mean: 61.6, standard deviation, SD: 14.7 years). They had been under treatment at the local pain clinic for 1.5 years on average. Musculoskeletal tissue disorders were present in more than two out of three patients and the greater was the analgesic step, the higher was their frequency (). These included, by decreasing frequency, osteoarthritis, intervertebral disc protrusions, back pain and fibromyalgia. Nervous system disorders followed in frequency, and patients were more commonly treated with step 1 medications. They typically featured sciatica and postherpetic neuralgia. Traumatic conditions and procedural sequels represented a minor contribution, as they were present in about 1 in 10 patients. The mean pain intensity fell within the ‘intense’ level (5 over 10), without differences among analgesic steps. More than half of the patients reported having ‘intense’ or worse pain intensity (). ‘Extreme’ and ‘the worst imaginable intensity’ levels were selected by 3.1% and 1.3% of patients, respectively. The adherence to pain medications was reported by investigators as ‘very good’ in 34.1% of patients and ‘good’ in 46.3% of patients. Just 65.9% of patients were reported to not have missed any analgesic dose during the prior week, and almost one in four was reported to have missed one or two doses. Adherence was better in patients receiving step 3 medications than in patients receiving steps 1 or 2 medications ().

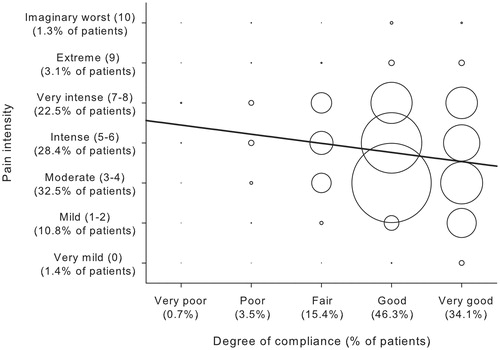

Figure 2. Bubble plot depicting the frequencies of each pain of responses given in the scales about pain intensity and pain medication adherence. The straight line represents the simple linear regression between these two variables. Their relationship was inverse.

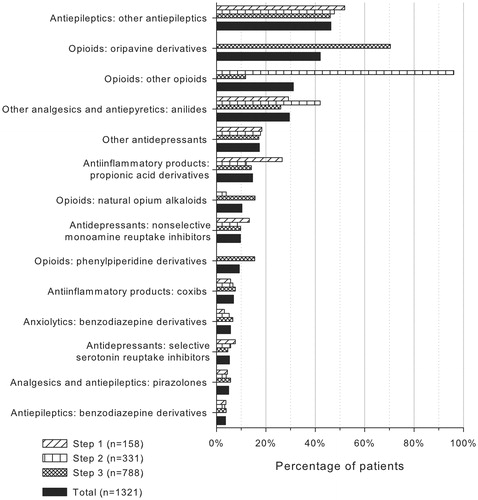

Figure 3. Medications for chronic nonmalignant pain prescribed at least to 3% of the patients comprising the study sample, coded at the fourth level of the WHO’s ATC classification system. The results from patients whose pain medications could not be staged (n = 44) were omitted for simplicity. WHO = World Health Organization; ATC = Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical.

Table 1. Patient characteristics by study groups (WHO's pain ladder).

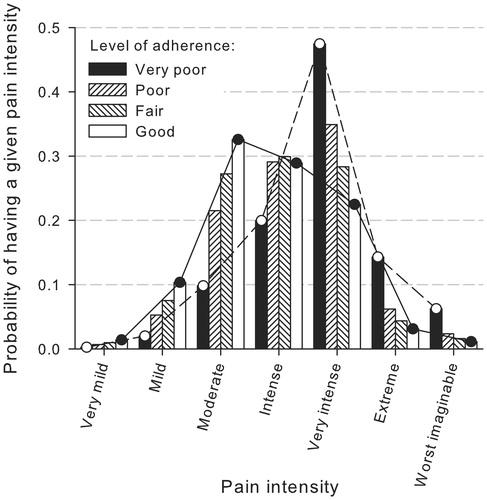

Lower pain intensity scores coincided more frequently with better levels of analgesic adherence in the same patient, and vice versa (). The corresponding Spearman’s correlation coefficient was small, but negative and significant (rs = −0.151; p < 0.001; 95% confidence interval, CI: −0.203 to −0.098). Mean pain intensity showed a statistically significant ascending pattern (F = 16.011; p < 0.001) that steadily increased as adherence worsened (4.6, 5.0, 5.4, 6.0 and 7.1 for the ‘very good’, ‘good’, ‘fair’, ‘poor’ and ‘very poor’ adherence levels, respectively). The presence of polypharmacy also related to worse patient adherence to pain medications (rs = −0.074; p = 0.007; 95% CI: −0.127 to −0.020). The multiple linear regression on pain intensity confirmed its inverse relationship with analgesic adherence. For each improvement in adherence level, pain intensity decreased by almost 0.5 points (). In this analysis, the presence of chronic medical conditions other than pain was also significantly associated with greater pain intensity and, strikingly, the polypharmacy showed an almost significant inverse association with pain intensity (lower intensity when medications unrelated to pain are present). The other variables considered were discarded because of lack of statistical significance. The proportion of variance explained by this model was very low (3%). The propensity scores on pain intensity () revealed that patients with poor adherence had a higher chance of suffering more pain than those with good adherence.

Figure 4. Propensity scores (probabilities) of each pain intensity level calculated for each adherence level after adjusting by potential confounding variables. The pain intensity level with the highest probability is that predicted for each adherence level (for example, patients with ‘good’ adherence – white bars – are expected to have moderate pain, whilst patients with ‘very poor adherence’ – black bars – are expected to have very intense pain).

Table 2. Multiple linear regression between pain intensity and patient adherence to pain medications and other variables.

Pain affected ‘much’ or ‘very much’ the quality of life of nearly 80% of patients, with only slight differences among study groups. Daily activities and mood were ‘much’ or ‘very much’ affected in about 50% of patients. The impact of pain on sleep was somewhat lower. Interestingly, the impact of pain on patient mood and sleep decreased as the step of pain medications increased, being thus lower among patients treated on step 3.

The drugs prescribed for CNCP are depicted in . The single ATC group most represented was other antiepileptics (in particular pregabalin and gabapentin). Anilides (in particular paracetamol) were the most common nonopioid analgesics, followed by propionic acid derivatives (in particular ibuprofen). Oripavine derivatives (buprenorphine) were the most common opioid analgesic, followed by natural opium alkaloids (in particular oxycodone). Other opioids (in particular tramadol) were common among patients treated on step 2. Atypical antidepressants (in particular duloxetine) were relatively common as well, whilst typical antidepressants (tricyclic, nonselective monoamine reuptake inhibitors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and benzodiazepines were rare. Nearly half of patients (46.2%) received three drugs to treat pain, 29.8% received two drugs and 12.4% received only one drug. The remaining patients received four or more drugs for their pain.

The most frequent chronic concurrent medical conditions were arterial hypertension (41.9% of patients), depression and dyslipidemia (each present in 27.3%), diabetes mellitus (17.3%), asthma (8.3%), myocardial ischemia (8.1%), and obesity (3.1%). More than half of the investigators did not think that taking medications unrelated to pain made it difficult for patients to take their pain medications. Also, about half of the investigators reported that the other medical conditions did not ‘affect’ or ‘slightly affect’ patient’s compliance with pain medications. Somewhat lower, however, was the proportion of investigators that reported that these conditions did not affect patient’s quality of life. In these three aspects, difficulties were deemed greater for patients receiving step 3 pain medications than for patients on lower steps.

Discussion

This clinical survey has systematically evaluated patients suffering from CNCP treated at pain clinics. The main findings showed that pain intensity and analgesic adherence had an inverse association, as did polypharmacy with analgesic adherence, despite the prevailing opinion of investigators that medications unrelated to pain did not affect it. Pain control remained unsatisfactory in many patients. Furthermore, the presence of chronic medical conditions other than CNCP was associated with higher pain intensity. As in prior reportsCitation1,Citation14,Citation15, most patients with CNCP were women, and the complaints associated with CNCP were commonly of musculoskeletal origin. However, in contrast with these reports based on the general population of patients with CNCP regardless of the specialty of the treating physicianCitation1,Citation15, potent opioids were prescribed profusely (in about 60% of patients) at pain clinics. Antiepileptics were also prescribed to many patients, but their preponderance may be regarded as artificial, because primary analgesic drugs are split across diverse ATC groups.

This research presents some strengths as well as some important limitations. The large sample size and the systematic recruitment procedure are positive features. Selection biases, with potential nonadherent patients refusing to participate in the studies more often, have been citedCitation9. However, there is always the possibility that the worse nonadherers did not consent to participate. Another positive feature is that thorough information was gathered on pain medication, in contrast with prior studies of CNCP. Conversely, because of its cross-sectional design, the assessment of temporal relationships between variables is not possible, which precludes the induction of any directional or causal association. Another limitation is the absence of an operational definition of nonadherence, including the distinction between medication underuse and overuse, which might be crucial to the advancement of CNCP management researchCitation8. Additionally, with the exception of pain intensity, the information collected was subjectively assessed by investigators. Health care providers tend to overestimate patient adherenceCitation6, and the study did not include any measure of inter-rater reliability. Simple, verbal subjective rating scales were used instead of validated clinical instruments that are available to measure quality of life and sleep, mood/depression, daily activities and, ultimately, adherence. Their use would have required more resources than those available for our survey. Conceivably, an even sharper association between pain intensity and adherence and a better fit of regression models might have been achieved with more reliable measuring instruments.

The influence of nonadherence to CNCP medication on outcome variables has not been widely evaluated and remains unclearCitation9. Two studies found a slight, but not significant decrease in pain among patients considered as adherentCitation16,Citation17. However, their sample sizes were much lower than that of the present research. Thanks to a considerable statistical power, the present study contributes by proving that an association between adherence to analgesic medication and pain intensity in CNCP conditions does exist. Such an association only explained a small proportion of the variability of pain intensity in the regression analyses. This is consistent with the notion that there are many influencing factors, but also implies that medication adherence could be a modifiable factor to improve therapeutic outcomes. As has been mentioned, this association does not warrant any causal relationship. It is also possible that the patients with less treatable diseases would find adherence more difficult. This assumption is consistent with the theory that patients’ beliefs about their disease and its treatment are central to adherenceCitation9, accepting that patients with less favorable outcomes have worse attitudes toward therapyCitation18,Citation19. In that case, interventions to improve patients’ attitudes might serve to obtain better outcomes.

As has been reportedCitation6,Citation9, polypharmacy hindered adherence to pain medications. This correspondence contrasted with the rather benevolent view of treating physicians who did not see this as a concern in more than half of the patients. A more thorough assessment of a patient’s adherence is thus warranted in patients who receive many medications, because they tend to neglect pain medication above allCitation12. So it is possible that adherence issues partially explain the association of other chronic pathologies with higher pain intensity. However, the almost significant association of polypharmacy with lower pain intensity is less clear. According to prior reasoning, these patients should have experienced worse pain if they avoided pain medication. But given the many factors that affect pain intensity (and the low predictive value of the regression analyses), there may be alternative explanations like, for example, that patients receiving care for many conditions tend to have more healthy attitudes.

A large proportion of patients were treated with potent opioids at pain clinics, in clear contrast with their lower utilization among patients with CNCP treated in other health care premisesCitation1,Citation15,Citation20. Although scientific evidence supports a role for chronic opioid therapy in CNCP if appropriate cautions are taken to maintain a favorable benefit-to-harm ratioCitation19,Citation21,Citation22, we are unable to determine whether or not these drugs were used appropriately in this study. The source population was restricted to patients referred to pain clinics. Therefore, it is plausible that nonopioid therapies had been tried in many patients before referral, but the study provided insufficient data to assess whether the required selection and monitoring of patients under chronic opioid therapy were adequate. Nonetheless, it is disappointing that, despite such use of potent opioids by specialized staff, as many as about 50% of patients did not experience adequate pain relief. This situation has not improved with respect to what was reported more than one decade agoCitation23.

Conclusions

This study has evidenced an association between CNCP and pain medication adherence, which had not been demonstrated by previous research. Such an association might represent a new avenue for improving therapeutic outcomes in CNCP by either promoting adherence or boosting patients’ attitudes to pain medication. Future studies should evaluate these interventions prospectively to elucidate causal relationships and provide evidence on effective strategies for improving outcomes, including disease course, utilization of resources and mortality. Pain specialists should be more aware of the negative impact that polypharmacy exerts on patients’ compliance to pain medications.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This research was funded by Grünenthal Pharma SA, Madrid, Spain.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

A.S. and I.S.-M. are full-time employees of Grünenthal Pharma SA.

M.R. has received fees from Grünenthal Pharma SA as clinical investigator.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Medicxact who acted as an external Medical Writing services provider and, in particular, Jesús Villoria, who drafted the manuscript, and provided technical and editorial assistance.

The results of this study were presented as a poster in the 13th World Congress on Pain held in Montreal (Canada) in August 2010.

References

- Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, et al. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287-333

- Hollon M. Nonmalignant chronic pain: taking the time to treat. Am Fam Physician 2009;79:743-4

- Pomm HA. Regaining balance after ‘reality vertigo:’ teaching learners to attend to the psychological aspects of patients with chronic, nonmalignant pain. Fam Med 2006;38:86-9

- Kalso E, Allan L, Dellemijn PLI, et al. Recommendations for using opioids in chronic non-cancer pain. Eur J Pain 2003;7:381-6

- Von Roenn JH. Are we the barrier? J Clin Oncol 2001;19:4273-4

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med 2005;353:487-97

- Scascighini L, Sprott H. Chronic nonmalignant pain: a challenge for patients and clinicians. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol 2008;4:74-81

- Broekmans S, Dobbels F, Milisen K, et al. Pharmacologic pain treatment in a multidisciplinary pain center: do patients adhere to the prescription of the physician? Clin J Pain 2010;26:81-6

- Broekmans S, Dobbels F, Milisen K, et al. Medication adherence in patients with chronic non-malignant pain: Is there a problem? Eur J Pain 2009;13:115-23

- Musi M. Lack of adherence with the analgesic regimen: the cancer patients’ perspective on a two-sided problem. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:2907-8

- McCracken LM, Hoskins J, Eccleston C. Concerns about medication and medication use in chronic pain. J Pain 2006;7:726-34

- Sale JE, Gignac M, Hawker G. How ‘bad’ does the pain have to be? A qualitative study examining adherence to pain medication in older adults with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:272-8

- Ventafridda V, Saita L, Ripamonti C, et al. WHO guidelines for the use of analgesics in cancer pain. Int J Tissue React 1985;7:93-6

- Casals M, Samper D. [Epidemiología, prevalencia y calidad de vida del dolor crónico no oncológico. Estudio ITACA. Rev Soc Esp Dolor 2004;11:260-9

- Rodríguez MJ. [Valoración de la actitud terapéutica ante el paciente con dolor crónico en las Unidades de Dolor de España. Estudio STEP]. Rev Soc Esp Dolor 2006;13:525-32

- Berndt S, Maier C, Schutz HW. Polymedication and medication compliance in patients with chronic non-malignant pain. Pain 1993;52:331-9

- de Klerk E, van der Linden SJ. Compliance monitoring of NSAID drug therapy in ankylosing spondylitis, experiences with an electronic monitoring device. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35:60-5

- Rosser BA, McCracken LM, Velleman SC, et al. Concerns about medication and medication adherence in patients with chronic pain recruited from general practice. Pain 2011;152:1201-5

- Noble M, Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, et al. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010: CD006605

- Galvez R. Variable use of opioid pharmacotherapy for chronic noncancer pain in Europe: causes and consequences. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2009;23:346-56

- Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Clinical guidelines for the use of chronic opioid therapy in chronic noncancer pain. J Pain 2009;10:113-30

- Paulozzi LJ, Weisler RH, Patkar AA. Commentary: a national epidemic of unintentional prescription opioid overdose deaths: how physicians can help control it. J Clin Psychiatry 2011;72:589-92 published online April 19, doi: 10.4088/JCP.10com06560

- Glajchen M. Chronic pain: treatment barriers and strategies for clinical practice. J Am Board Fam Pract 2001;14:211-18