Abstract

Objective:

To examine healthcare cost patterns prior to and following duloxetine initiation in patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), focusing on patients initiated at or titrated to high doses.

Research design and methods:

Retrospective analysis of 10,987 outpatients, aged 18–64 years, who were enrolled in health insurance for 6 months preceding and 12 months following duloxetine initiation.

Outcome measures:

Repeated measures and pre–post analyses were used to examine healthcare cost trajectories before and after initiation of low- (<60 mg/day), standard- (60 mg/day), and high-dose (>60 mg/day) duloxetine therapy. Decision tree analysis was used to identify patient characteristics that might explain heterogeneity in economic outcomes following titration to high-dose therapy.

Results:

Low-, standard-, and high-dose duloxetine were initiated for 29.6%, 60.9%, and 9.5% of patients, respectively. Within 6 months, 13.7% of patients had dose increases to > 60 mg/day. Regardless of dose, total costs increased prior to and decreased following initiation of treatment. The High Initial Dose Cohort had higher costs both prior to and throughout treatment compared to the other two cohorts. Following escalation to > 60 mg/day, higher medication costs were balanced by lower inpatient costs. Titration to high-dose therapy was cost-beneficial for patients with histories of a mental disorder in addition to MDD and higher prior medical costs.

Limitations:

Conclusions are limited by a lack of supporting clinical information and may not apply to patients who are not privately insured.

Conclusions:

In data taken from insured patients with MDD who were started on duloxetine in a clinical setting, healthcare costs increased prior to and decreased following initiation of therapy. Compared to patients initiated at low- and standard-doses, costs were greater prior to and following initiation for patients initiated at high doses. Increases in pharmacy costs associated with escalation to high-dose therapy were offset by reduced inpatient expenses.

Introduction

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is among the most prevalent and costly psychiatric disordersCitation1,Citation2. Antidepressants are the mainstay treatment for adults with MDD. Duloxetine is a second-generation antidepressant and has demonstrated efficacy, safety, and tolerability in patients with MDD in a number of randomized clinical trialsCitation3–6. Duloxetine is approved for treatment of MDD at starting doses of 40 or 60 mg/day, acute treatment target doses of 40 to 60 mg/day, a maintenance treatment target dose of 60 mg/day, and a maximum dose of 120 mg/dayCitation7. No significant clinical differences in efficacy have been observed between doses of 60 mg/day and >60 mg/day in clinical trialsCitation6. However, in an analysis of data from 6132 commercially insured patients with MDD initiated on duloxetine during 2005 and 2006, high-dose duloxetine (>60 mg/day) was prescribed for ∼25% of patients at some point during 12 months of observationCitation8.

Duloxetine is available in 20 mg, 30 mg, and 60 mg tabletsCitation7, and so treatment at 120 mg/day costs approximately twice that of treatment at 60 mg/day. It is unknown if use of higher duloxetine doses in usual care is beneficial from a clinical or economic perspective, and, specifically, whether the increase in pharmacy cost associated with high-dose therapy is offset by decreases in medical expenses. In addition, it is important to understand if there are factors that identify patient sub-groups with greater or lesser benefit from high-dose therapy. Answers to these questions have important implications for patients, clinicians, and payers.

To date, researchers have investigated initial duloxetine prescription doses (Xianchen Liu, MD, unpublished data, 2010), treatment adherence and persistence based on initial duloxetine doseCitation8, dosing and treatment patterns of duloxetine in US managed-care patients with MDDCitation9, and demographic and clinical predictors of high-dose duloxetine use (Xianchen Liu, MD, unpublished data, 2010). In the latter study, patients treated with high-dose duloxetine were observed to be complicated both medically and psychiatrically. They were older, had more comorbid neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, dysthymic disorder, and prior injury or poisoning. They were also more likely to have been seen by a psychiatrist, and to have had prior use of psychostimulants, benzodiazepines, venlafaxine, or atypical anti-psychotics. However, little is known about healthcare expenditures associated with high-dose duloxetine therapy and about which patients with MDD might experience a cost benefit from use of high-dose therapy.

The objectives of this study were to examine healthcare cost patterns prior to and following duloxetine initiation in patients with MDD, with a focus on the cost patterns for patients initiated at high-dose therapy.

Duloxetine is most often initiated as second-line therapy following treatment failure with a primary agent; therefore, we hypothesize that total healthcare costs will increase in the months prior to initiation of duloxetine as a reflection of this failure. We further hypothesize that costs will decrease following initiation of duloxetine, and that this will be especially apparent when high-dose therapy is used. A secondary objective was to explore whether specific patient characteristics could potentially explain any heterogeneity in economic outcome within the population of patients who experienced titration to high doses.

Patients and methods

Data source and patient selection

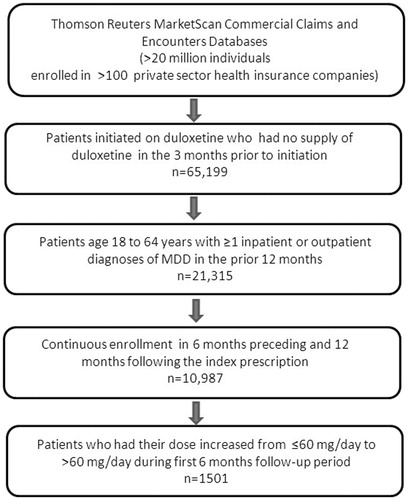

This was a retrospective analysis of medical, pharmacy, and enrollment data from the Thomson Reuters MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database. All records included for consideration were from patients who were initiated on duloxetine during the 2007 calendar year and did not have a prescription claim for duloxetine in the previous 3 months or a claim for duloxetine for which the expected days’ supply of medication would have carried over into the 3-month window prior to initiation (n = 65,199). Included patients had at least one inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of MDD in the previous 12 months (ICD-9-CM codes 296.2 [single episode] and 296.3 [recurrent episode]), were between the age of 18–64 years, and had continuous insurance enrollment for 6 months preceding and 12 months following the index duloxetine dose (n = 10,987) ().

Statistical analysis

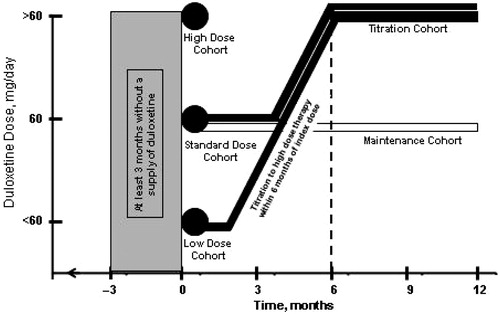

Doses of duloxetine for each patient were calculated using the formula, quantity × strength/days’ supply of medication, and low (<60 mg/day), standard (60 mg/day), and high initial dose (>60 mg/day) cohorts were identified based on initial dose prescribed. Dosing matrices of initial dose prescribed vs maximal dose prescribed through months 6–12 of treatment were constructed. From these matrices, two additional cohorts were identified: one comprised of patients who began treatment at a low or standard dose, but whose maximal dose was >60 mg/day in the first 6 months post-initiation (Titration Cohort), and one comprised of patients maintained at a dose of 60 mg/day throughout the 12-month follow-up period (Maintenance Cohort). The former was used to assess healthcare costs before and after titration to high-dose therapy, and the latter served as a reference. The 6-month time period for the Titration Cohort was chosen to ensure the completeness of healthcare cost data from the post-titration period ().

Figure 2. Study design showing the five cohorts: three groups identified by the initial duloxetine dose prescribed (High, Recommended, and Low Initial Dose Groups); a group in which the duloxetine dose was increased to >60 mg/day at some point within 6 months of the index dose (Titration Cohort); and a group that remained on a duloxetine dose of 60 mg/day throughout the 12-month study.

Summary statistics were used to describe baseline demographics, clinical characteristics, and healthcare costs for the five cohorts and for the total study population. Healthcare costs in the 6 months preceding initiation of duloxetine were compared between cohorts using a non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables and t-tests were used for continuous variables. Healthcare costs at each time point in the 6 months preceding and the 12 months following the index prescription were compared between initial dosing cohorts using a repeated measures linear mixed model with dose, month, and dose*month as fixed effects and patient (dose) as a random effect. Rate of healthcare cost change (slope) prior to and following initiation of duloxetine were estimated using separate linear regression models for each initial dosing cohort and each time period. The inclusion criteria specified a 3-month duloxetine-free period preceding the index dose and the pre–post cost analysis of cost data extended to 6 months preceding the index dose, so a small percentage of patients (∼3.5%) had been exposed to duloxetine in the time period between month 6 and month 3 prior to the index dose. However, to keep the time periods under comparison similar between patient groups, these patients were included in the analysis. Given the skewed nature of the cost data, bootstrapping was used to provide a non-parametric assessment of the variability of the cost trend estimates, and to provide a sensitivity analysis.

Paired t-tests were used to assess differences between itemized healthcare costs in the 3 months preceding and the 3 months following dose initiation for patients in the High Initial Dose Cohort and for the 3 months surrounding dose escalation for patients in the Titration Cohort. Sensitivity pre–post analyses were conducted, removing hospitalization costs in the first post-week period, because these hospitalizations might have been due in part to a failure of the previous medication, or due to events at the end of the pre-periodCitation10.

In an exploratory analysis, a recursive partition method (classification and regression tree [CART] analysisCitation11,Citation12) was employed using SAS Enterprise Miner 5.2 to explore key predictors that might impact heterogeneity in cost outcomes for patients in the Titration Cohort. Specifically, we sought to identify sub-groups of patients who experienced a cost benefit with dose escalation. In the CART analysis, the full patient population was repeatedly divided into smaller, more homogeneous groups in order to maximize the pre–post differences of total healthcare costs, and costs for psychiatric care and depression-related care. This was accomplished by generating an ordered list of predictors of cost benefit (pre–post cost differences) from ‘best’ to ‘worst’ based on log(p) from a regression model in SAS Enterprise Miner; then, by finding the optimal split for the best predictor to partition the cohort into two sub-groups resulting in a ‘promising’ cost beneficial sub-set and a ‘non-promising’ cost beneficial sub-set. The process was repeated on each sub-set until the resulting sub-sets were not statistically different (i.e., p ≥ 0.05) from one another using an F-test.

Results

Dosing patterns

Dosing patterns from time of initiation through months 6 and 12 are shown in and , respectively. Of the 10,987 patients in this analysis, 61% (n = 6686) initiated duloxetine at the standard dose, 60 mg/day. During the 6-month follow-up period, 76% (5071/6686) of patients initiated at the standard dose had persisted with that dose or discontinued duloxetine therapy. During the 12-month follow-up period, that number fell to 67% (n = 4486/6686). These 4486 patients comprised the Maintenance Cohort. Of the remaining 2200 patients, 560 received a dose of <60 mg/day, and 1640 received a dose of >60 mg/day. The Titration Cohort consisted of 1501 patients whose maximal dose was >60 mg/day; 281 patients from the Low Initial Dose Cohort and 1220 from the Standard Initial Dose Cohort.

Table 1. Dosing patterns from initiation through month 6 for patients with major depressive disorder treated with duloxetine.

Table 2. Dosing patterns from initiation through month 12 for patients with major depressive disorder treated with duloxetine.

Demographics by cohort

Three out of every four patients who met eligibility criteria were female (8190/10,987, 75%) and the mean age was 46 years (SD 11.0 years) (). Patients were most commonly from the South (4724/10,987, 43%), with the remainder predominantly distributed in the North Central (3003/10,987, 27%) and Western (2236/10,987, 20%) regions. The majority of patients (6476/10,987, 59%) had insurance coverage through a preferred provider organization. Compared to patients in the Low and Standard Initial Dose Cohorts, patients in the High Initial Dose Cohort were numerically older and more likely to have insurance through a point-of-service plan rather than a health maintenance organization. They also appeared to have a greater incidence of painful medical conditions and bipolar disorder. Compared to the Maintenance Cohort, patients in the Titration Cohort had numerically greater rates of painful medical conditions, sleep disorders, and bipolar disorder. Total healthcare costs were statistically greater (p < 0.001) in the 6 months preceding duloxetine initiation for patients in the High Initial Dose Cohort compared to patients in the Standard and Low Initial Dose Cohorts ($11,229 vs $8330 and $7947, respectively), and for the Titration Cohort ($10,147) compared to the Maintenance Cohort ($7862).

Table 3. Demographic information and clinical characteristics for all included patients and for patients in five cohorts, including three initial dose cohorts, a titration cohort, and a maintenance cohort.

Total healthcare costs prior to and following initiation of duloxetine

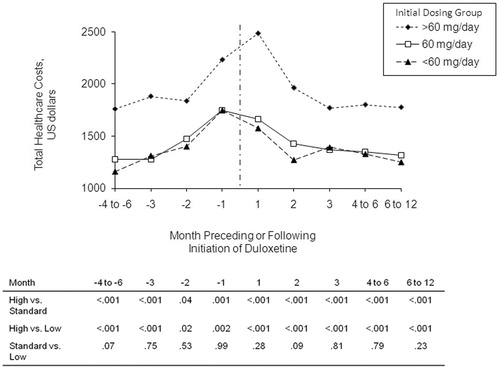

For patients in the Low, Standard, and High Initial Dose Cohorts, healthcare cost increases were noted as early as 6 months prior to the index dose of duloxetine (range of cost increase = $98/month to $133/month); in the 3 months preceding that dose, the rate nearly doubled for all initial dose groups (range: $175/month to $232/month) (). In the 3 months following the initial dose, patients in the Low, Standard, and High Initial Dose Cohorts had reductions in healthcare cost at rates of $92/month (p = 0.07), $146/month (p < 0.001), and $357/month (p < 0.001), respectively. Less dramatic declines in total healthcare costs were seen thereafter. Bootstrap-derived confidence intervals for the rate of cost change did not cover the value 0, which confirmed the results based on linear regression models.

Table 4. Rate of cost change (US dollars/month) prior to and following initiation of duloxetine in patients with major depressive disorder.

As shown in , patients in the Low and Standard Initial Dose Cohorts had statistically significantly higher total healthcare costs at each time point in the 6 months preceding and the 12 months following the index prescription (all p < 0.05).

Pre–post analysis of healthcare costs

The total healthcare cost for the High Initial Dose Cohort was numerically greater in the 3 months following the index dose compared to this cost in the 3 months preceding initiation ($457, p = 0.13) (). Increased pharmacy expenses ($902, p < 0.001) for both antidepressants ($611, p < 0.001) and other prescriptions ($290, p < 0.001) were not entirely offset by reductions in cost for inpatient care (−$690, p = 0.008), which were largely attributable to reductions for care of depression-related illness (−$724, p < 0.001). For patients in the Titration Cohort, there was essentially no change in total healthcare cost between the 3 months preceding and 3 months following titration to high-dose duloxetine ($6, p = 0.98). Increases in pharmacy expense ($652, p < 0.001) were offset by decreases in outpatient (−$122, p = 0.29) and inpatient (−$524, p = 0.002) healthcare costs. The decrease in inpatient costs was driven by costs related to care of depression (−$490, p < 0.001) and psychiatric illness (−$441, p < .001) rather than by costs for care unrelated to psychiatric illness (−$83, p = 0.53) ().

Table 5. Differences in itemized healthcare costs between the 3 months preceding and the 3 months following initiation of duloxetine for the high dose initiation cohort, following escalation to high-dose therapy for the titration cohort, and for all patients included in the analysis.

Sensitivity analyses removing first week hospitalization costs from the post-initial dose period resulted in similar inferences as the original analysis, with non-significant mean decreases in total costs for the High Initial Dose group.

Exploratory sub-group analyses using classification and regression tree analysis

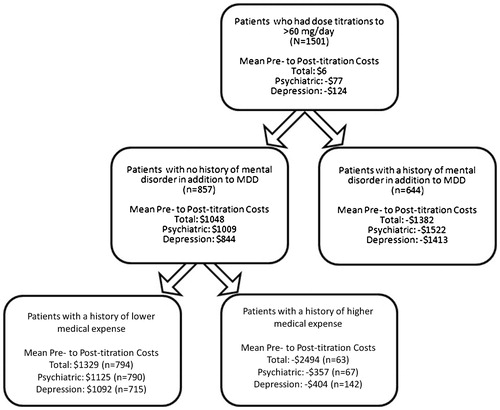

Because change in total healthcare costs, psychiatric care, and care for depression did not change following the dose escalation in the Titration Cohort, we used CART analysis to identify a cost-beneficial sub-group with significantly reduced post-titration costs. The CART model identified a patient’s prior level of healthcare spending and history of a mental disorder in addition to MDD as the most important predictors of change in healthcare costs for patients in the Titration Cohort. Patients who had had an additional mental disorder and whose medical costs in the 3 months prior to duloxetine initiation had been high (>$6752 for total healthcare costs, >$6538 for psychiatric care costs, and >$3437 for depression-related care costs) were more likely to experience a cost benefit following dose escalation (). The sub-groups meeting these criteria accounted for close to half of the 1501 patients (47% for total healthcare costs, 47% for psychiatric care costs, and 52% for depression-related costs). Cost benefit with dose escalation appeared to be due primarily to decreases for care of depression-related illness.

Figure 4. Results of classification and regression tree (CART) analyses identifying those patients who experienced reductions in healthcare costs following a dose increase to >60 mg/day in the first 6 months of duloxetine treatment. In each of the three analyses, a history of a mental disorder in addition to major depressive disorder (MDD) and a history of prior higher medical expenses in the 6 months preceding duloxetine initiation identified patients more likely to experience a cost benefit. Breakpoints for higher vs lower past medical expenses were ≥$6752, ≥$6538, and ≥$3437 for the algorithms related to total healthcare cost savings, psychiatric care cost savings, and depression care cost savings, respectively.

Discussion

In this retrospective analysis of health insurance claims data from more than 10,000 patients who were started on duloxetine for treatment of MDD, repeated measures analysis showed total healthcare costs increased in the 6 months leading to treatment initiation and decreased over the following 12 months. When compared to patients started at low- or standard-dose duloxetine, patients who were started on high-dose duloxetine had higher total healthcare costs leading up to duloxetine initiation and throughout the course of treatment. An analysis of specific healthcare costs pre- and post-escalation revealed increased spending on medication and decreased spending on inpatient services, such that there was no change in overall healthcare expense associated with increasing the dose for duloxetine. Patients with a history of high medical costs and with at least one mental disorder in addition to MDD were more likely to experience a cost benefit with titration to high-dose therapy.

Compared to dosing patterns seen in another recent analysis of claims data that included 6132 patients who met similar entry criteria (Xianchen Liu, MD, unpublished data, 2010), patients in this analysis were more frequently started on high-dose therapy (9.5% vs 6.5%), less frequently treated with maximal high-dose therapy (28.2% vs 34.4%), and more frequently increased from standard- or low-dose therapy to high-dose therapy (18.7% vs 17.7%) in the 12 months post-duloxetine initiation. These differences may reflect differences in the time period during which the data were collected (2005–2006 for the previous study vs 2007–2008 for this study). In the previous analysis, patients treated with high-dose therapy had more medical comorbidity and greater use of psychoactive medication and pain medication than patients treated with low- or standard-dose therapy. This analysis of cost patterns by dose supports the conclusion that patients treated with high-dose duloxetine are medically and psychiatrically complex.

The observed increase in healthcare spending prior to initiation of duloxetine was consistent with the idea that some degree of clinical deterioration generally precedes a change in treatment strategy, and, in this database, that change was the initiation of duloxetine. While there have been some between-group comparative cost analyses of treatments for MDDCitation13–16, this is, to the authors’ knowledge, the first detailed repeated measures analysis of healthcare costs surrounding initiation of treatment for this condition. The apparent inconsistency between the lack of change in total spending following duloxetine initiation in the pre–post analysis and the decrease in post-initiation spending in the repeated measures analysis is not contradictory. The baseline period for the pre–post analysis was a 3-month window of varying costs, while the repeated measures analysis looked at the trend in cost, beginning at the point of medication initiation.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Data were obtained from a health insurance claims database rather than generated through a prospective study or by post-hoc evaluation of patient charts. Therefore, clinical information including a patient’s sub-type of depression, the presence or absence of somatic symptoms, duration of illness, and severity of the index depressive episode (as assessed by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression or other validated instrument) was not available that might have explained the cost patterns observed in this analysis. All patients in this analysis were privately insured, so these findings may not apply to patients who are self-pay, enrolled in Medicare or Medicaid, or who pay for mental health care in some other way. Likewise, it is unknown if the findings from patients who were part of the Thomson Reuters MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Database can be generalized to patients whose claims are included in other databases. Information in a claims database does not undergo the quality control measures employed in a clinical trial. Still, there is no reason to suspect that potential inaccuracies would have resulted in any dose-related bias. Claims databases also lack detailed information on clinical outcomes, and so their possible relationship to cost differences across doses could not be explored.

As described in the Methods, the inclusion criteria included a 3-month duloxetine-free period preceding the index dose, but pre–post cost analyses extended back 6 months prior to the index dose. This meant that the cost data for ∼3.5% of the population included 3 months in which patients had been exposed to duloxetine. Although this is acknowledged as a limitation of the study design, it is unlikely to have altered the findings.

This study design involved use of within-group comparisons over time such as pre–post cost differences. Such comparisons do not fully address broader economic issues related to treatment strategy. For example, though the data showed cost neutrality following an increase to high-dose duloxetine, it provided no information as to whether remaining on the same dose, augmenting treatment with additional medication, or switching to a different antidepressant would have resulted in a superior economic outcome, or in additional clinical or quality-of-life measures. Further research in this area is needed.

Another limitation was the lack of an available patient population to test the validity of the CART-derived model explaining patient heterogeneity in economic response. Data from the entire population of patients meeting eligibility criteria were utilized in the analysis without holding back a portion of the data for validation. Also, had clinical factors been contained in the claims database, their inclusion might have strengthened the model.

In this study, daily duloxetine doses were estimated based on insurance claims form data rather than on monitored consumption of medication, which may have led to some degree of distortion in the results. Also, it was unknown which patients discontinued treatment, why they discontinued treatment, and what effect discontinuation had on healthcare spending through the duration of the study. Also, although payments for healthcare by commercial insurers were included in this analysis, other depression-related expenses such as out-of-pocket spending and costs related to time away from work due to disability were not included.

Finally, the focus of this analysis was on describing the healthcare cost patterns associated with the dose at which duloxetine was initiated and associated with titration to higher dose therapy. Whether the differences observed between cohorts were causally related to duloxetine dose is not clear. Future analyses in this area should include a quantitative assessment of the impact of duloxetine dose and potential unmeasured clinical confounding variables.

Conclusion

In this analysis of data from a large health insurance claims database, healthcare costs increased prior to the initiation of duloxetine therapy, perhaps signaling a clinical deterioration that led to a change in treatment strategy. Healthcare costs decreased following initiation of duloxetine. Compared to patients who were given low- or standard-dose therapy, patients who received high-dose duloxetine had higher healthcare expenses both prior to and following the index prescription. Titration to high-dose therapy was found to be cost neutral, with increases in pharmacy costs largely offset by reduced inpatient care costs.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Financial support was provided by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. Employees of Lilly were involved in the study design, analysis of data, and in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

At the time this manuscript was written, ZC, DF, YZ, DN, and XL were full-time employees of Eli Lilly and Company and/or one of its subsidiaries, and were minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation is expressed to Tamara Ball, MD, for writing and editorial contributions. Dr Ball is a scientific writer employed full-time by i3 Statprobe, part of the inVentiv Health Company. Eli Lilly and Company contracted the technical writing of this manuscript with i3 Statprobe. Also acknowledged are: Steve Able and Wei Shen of Eli Lilly and Company for critical review of this manuscript, and Teri Tucker and Casey Brackney of i3 Statprobe for editorial review of this manuscript.

References

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:593–602

- Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, et al. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:1465–75

- Detke MJ, Lu Y, Goldstein DJ, et al. Duloxetine 60 mg once daily dosing versus placebo in the acute treatment of major depression. J Psychiatr Res 2002;36:383–90

- Detke MJ, Lu Y, Goldstein DJ, et al. Duloxetine, 60 mg once daily, for major depressive disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:308–15

- Detke MJ, Wiltse CG, Mallinckrodt CH, et al. Duloxetine in the acute and long-term treatment of major depressive disorder: a placebo- and paroxetine-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2004;14:457–70

- Goldstein DJ, Mallinckrodt C, Lu Y, et al. Duloxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder: a double-blind clinical trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63:225–31

- Cymbalta [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN: Eli Lilly and Company, 2011

- Liu XC, Gelwick S, Faries D, et al. Initial duloxetine prescription dose and treatment adherence and persistence in patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacology 2010;25:315–22

- Venturini F, Sung JCY, Nichol MB, et al. Utilization patterns of antidepressant medications in a patient population served by a primary care medical group. J Manag Care Pharm 1999;5:243–9

- Faries DE, Nyhuis AW, Ascher-Svanum H. Methodological issues in assessing changes in costs pre- and post-medication switch: a schizophrenia study example. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2009;7:11

- Breiman L, Freidman L, Olshen RA, et al. Classification and regression trees. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 1984

- Lemon SC, Roy J, Clark MA, et al. Classification and regression tree analysis in public health: methodological review and comparison with logistic regression. Ann Behav Med 2003;26:172–81

- Weilburg JB, Stafford RS, O'Leary KM, et al. Costs of antidepressant medications associated with inadequate treatment. Am J Manag Care 2004;10:357–65

- Russell JM, Berndt ER, Miceli R, et al. Course and cost of treatment for depression with fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline. Am J Manag Care 1999;5:597–606

- Panzarino PJ Jr, Nash DB. Cost-effective treatment of depression with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Am J Manag Care 2001;7:173–84

- Camacho F, Kong MC, Sheehan DV, et al. Expenditures associated with dose titration at initiation of therapy in patients with major depressive disorder: a retrospective analysis of a large managed care claims database. P T 2010;35:452–68