Abstract

Objective:

To assess the cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate (‘dabigatran’) vs vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) in the Belgian healthcare setting for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism (SE) in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF).

Research design and methods:

A Markov model was used to calculate the cost-effectiveness of dabigatran vs VKAs in Belgium, whereby warfarin was considered representative for the VKA class. Efficacy and safety data were taken from the Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trial and a network meta-analysis. Local resource use and unit costs were included in the model. Effectiveness was expressed in Quality Adjusted Life-Years (QALYs). The model outcomes were total costs, total QALYs, incremental costs, incremental QALYs and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The level of International Normalized Ratio (INR) control and the use of other antithrombotic therapies observed in Belgian clinical practice were reflected in two scenario analyses.

Results:

In the base case analysis, total costs per patient were €13,333 for dabigatran and €12,454 for warfarin. Total QALYs per patient were 9.51 for dabigatran and 9.19 for warfarin. The corresponding ICER was €2807/QALY. The ICER of dabigatran was €970/QALY vs warfarin with real-world INR control and €5296/QALY vs a mix of warfarin, aspirin, and no treatment. Results were shown to be robust in one-way and probabilistic sensitivity analyses.

Limitations:

The analysis does not include long-term costs for clinical events, as these data were not available for Belgium. As in any economic model based on data from a randomized clinical trial, several assumptions had to be made when extrapolating results to routine clinical practice in Belgium.

Conclusion:

This analysis suggests that dabigatran, a novel oral anticoagulant, is a cost-effective treatment for the prevention of stroke and SE in patients with non-valvular AF in the Belgian healthcare setting.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common heart arrhythmia with a prevalence that is currently estimated at 1–2% of the general populationCitation1, reaching over 10% in patients aged 80 or moreCitation2. A recent screening program in Belgium identified AF in ∼2% of respondents aged over 40Citation3. The number of AF patients has increased during the past yearsCitation2,Citation4,Citation5 and is expected to increase even more over the next decadesCitation4. Patients with AF have a 5-fold risk of suffering a stroke and are also at increased risk of systemic embolism (SE)Citation6,Citation7. AF places a burden on patients and their families, but also on society, as the costs of stroke are highCitation8.

Until recently international guidelines recommended long-term anticoagulant treatment with vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) for moderate-to-high risk AF patients, with a target International Normalized Ratio (INR) between 2–3Citation1,Citation9,Citation10. Warfarin reduces the risk of stroke by 64% compared to placebo in non-valvular AFCitation11. However, VKAs have several drawbacks. They present numerous drug–drug and food–drug interactionsCitation1. They also have a narrow therapeutic window and the anticoagulant effect is unpredictable, with a high inter- and intra-individual response variabilityCitation1. The INR has to be monitored on a regular basis to avoid putting patients at increased risk of ischemic stroke (IS) if the INR is below 2 and at increased risk of hemorrhagic events such as intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) if the INR is above 3Citation9. The average time in therapeutic range (TTR) observed in daily clinical practice is often lower than the TTR values achieved in clinical trialsCitation12,Citation13. In Belgium, AF patients have an average TTR of 53%Citation14. Moreover, due to the many limitations of VKAs, AF patients often do not receive VKA treatment and are instead treated with aspirin or not treated at allCitation15–17. In view of the limitations of VKA treatment and their sub-optimal use, there is a clear need for an efficient, safe and more convenient stroke prevention treatment for AF.

Dabigatran etexilate (‘dabigatran’) is a new oral direct thrombin inhibitor with a predictable anticoagulant effect and no need for routine monitoring. The efficacy and safety of dabigatran 110 mg twice daily and dabigatran 150 mg twice daily vs adjusted-dose warfarin were assessed in the large Randomized Evaluation of Long-Term Anticoagulation Therapy (RE-LY) trialCitation18,Citation19. Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily significantly reduced the rate of stroke and SE and had a similar rate of major hemorrhage compared to warfarin (RR = 0.65, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) = 0.52–0.81, p < 0.001 for stroke and SE; RR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.81–1.07, p = 0.31 for major hemorrhage). Dabigatran 110 mg twice daily was non-inferior to warfarin in terms of stroke and SE risk reduction and significantly reduced the rate of major hemorrhage compared to warfarin (RR = 0.90, 95% CI = 0.74–1.10, p = 0.29 for stroke and SE; RR = 0.80, 95% CI = 0.70–0.93, p = 0.003 for major hemorrhage). Both doses were significantly superior to warfarin in reducing the rate of intracranial hemorrhage (ICH) (RR = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.28–0.60, p < 0.001 for dabigatran 150 mg twice daily; RR = 0.30, 95% CI = 0.19–0.45, p < 0.001 for dabigatran 110 mg twice daily) and hemorrhagic stroke (HS) (RR = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.14–0.49, p < 0.001 for dabigatran 150 mg twice daily; RR = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.17–0.56, p < 0.001 for dabigatran 110 mg twice daily). Dabigatran is approved in Europe since August 2011 for stroke prevention in non-valvular AF patients with at least one risk factor and is reimbursed for the same indication in several EU countries, among which Belgium.

As decisions around resource allocation become more difficult due to rising healthcare expenditures and budget constraints, it is important to evaluate dabigatran not only in terms of clinical efficacy and safety but also in terms of cost-effectiveness. In other words, does dabigatran offer good value for money in the prevention of stroke for AF patients? The present article presents a cost-utility analysis of dabigatran vs VKAs in the Belgian healthcare system. The cost-effectiveness of dabigatran in the prevention of stroke in AF patients has recently been assessed in the Canadian, UK, Danish, and Swedish settingsCitation20–24. The analysis in the Belgian setting is useful to assess the convergent validity of the results observed in the other countries.

Methods

Overview

A Markov model was used to estimate the cost-effectiveness of dabigatran in the prevention of stroke and SE in eligible AF patients in Belgium. The model was previously described in detail and has been adapted in several countriesCitation20,Citation22,Citation23,Citation25. The model follows eligible AF patients throughout the course of their disease in 3-months cycles, from start of antithrombotic treatment until death. Patients transition between a finite number of health states, defined by their treatment status, their stroke history, and their disability level. Relevant clinical events are included in the model and baseline event risks and relative risks are sourced from the RE-LY trial (for dabigatran and warfarin) and a published network meta-analysis (for aspirin and no treatment)Citation18,Citation19,Citation26. Outcomes of the model include total costs and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), incremental costs and QALYs, and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The model was adapted to the Belgian setting by using national all-cause mortality rates, local resource use data, and local unit costs. Acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon are used as often as warfarin in Belgian clinical practice; this VKA group as a whole was, therefore, considered as the relevant comparator for dabigatran in the cost-effectiveness analysis. As the comparator in the RE-LY trial was warfarin, this molecule was considered representative of the VKA class in terms of efficacy and safety in our analysis. Although the model allows the inclusion of long-term follow-up costs for clinical events, only acute event costs were included in our analysis, as appropriate long-term costs of stroke and ICH in Belgium are scarce.

Patient population

The model was populated with a cohort of 10,000 AF patients whose baseline characteristics match those of the patients aged below 80 included in the RE-LY trialCitation18,Citation19. The mean age was 69 years and 65% of patients were male. CHADS2 scores were distributed as follows: 0 (3.0%), 1 (32.6%), 2 (34.4%), 3 (19.5%), 4 (7.7%), 5 (2.4%) and 6 (0.4%). 20% of patients experienced a previous stroke.

Model structure

Patients in the model transition between distinct health states, defined by their treatment status (on or off treatment), their disability level (independent, moderately dependent, and totally dependent), and their stroke history (prior or no prior stroke). Clinical events included in the model are: ischemic stroke (IS), hemorrhagic stroke (HS), transient ischemic attack (TIA), systemic embolism (SE), intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), major extracranial hemorrhage (ECH), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), minor bleed, and death. Baseline event risks and relative risks are taken from the RE-LY trial (for warfarin and dabigatran)Citation18,Citation19 and from a network meta-analysis (for aspirin and no treatment)Citation26. IS, HS, and ICH are assumed to be disabling or non-disabling events. Disability levels were defined according to the modified Rankin Scale for IS and HS (independent: score ≤2; moderately dependent: score 3 or 4; totally dependent: score 5) and the Glasgow Outcomes Scale for ICH (independent: score 5; moderately dependent: score 4; totally dependent: score ≤3). Ninety days post-event disability levels were estimated from the RE-LY trialCitation18,Citation19 and from the literatureCitation27,Citation28. Belgian all-cause mortality rates were included in the modelCitation29. Utility values attributed to each disability level and utility decrements associated with the clinical events were taken from the literatureCitation30,Citation31. The baseline event rates, hazard ratios, and utility values have been presented elsewhereCitation20. Patients discontinue treatment permanently after a HS or an ICH. An ECH can lead to continuation, temporary discontinuation, or permanent discontinuation of treatment. Patients can also permanently discontinue treatment or switch to treatment with aspirin for other, non-clinical reasons (e.g., burden of INR monitoring).

Treatments and model scenarios

Patients entering the model receive either dabigatran or adjusted-dose warfarin. Patients under the age of 80 receive dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and then switch to dabigatran 110 mg twice daily once they reach the age of 80, in line with the approved European labelCitation32. In the base case analysis, dabigatran is compared to warfarin with ‘trial-like’ INR control, using the average TTR observed in the warfarin arm of the RE-LY trial (64%). In order to better reflect the degree of INR control observed in Belgian clinical practice and the use of other antithrombotic treatments in AF patients, two scenario analyses were conducted. Dabigatran was, on the one hand, compared to warfarin with ‘real-world’ INR control, using TTR values observed in Belgian clinical practice, and, on the other hand, to a treatment mix composed of warfarin, aspirin, and no treatment. The average TTR in Belgian clinical practice is estimated at 53%Citation14 and the percentage of AF patients receiving warfarin (47%), aspirin (35%), or no treatment (18%) was calculated from Thijs et al.Citation16. The efficacy and safety of warfarin is influenced by the TTR; ischemic and hemorrhagic events occur more frequently if the TTR is less optimal than in a clinical trial setting. The difference in outcomes with warfarin treatment between the ‘trial-like’ and ‘real-world’ scenarios was integrated in the model by adjusting baseline event risks for warfarin with data from the literatureCitation33,Citation34. In all scenarios patients could be switched to aspirin treatment after permanent discontinuation of dabigatran or warfarin.

Resource use and unit costs

The model includes direct medical costs, i.e., drug costs, the cost of INR monitoring, and the acute cost of all clinical events. An average cost for VKAs was calculated to reflect Belgian treatment patterns, as acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon are used as often as warfarin. The cost per Daily Defined Dose (DDD) for each VKA was weighted by its market share expressed in units. The cost of INR monitoring includes the cost of general practitioner (GP) visits and the cost of the laboratory test. Patients are tested on average 18 times per yearCitation35. Every test is associated with one GP visit, but it was assumed that patients receiving dabigatran would still maintain four GP visits per year, therefore 14 incremental GP visits were included in the cost calculation for INR monitoringCitation35. Unit costs for drugs and INR monitoring were sourced from official national tariffs and nomenclatureCitation36,Citation37. Clinical event costs represent hospitalization costs and were retrieved from a large database containing clinical and financial data of over 20 hospitals in Belgium (Unité de Socio-Economie de la Santé, Faculty of Public Health, UCL, 2010). The database includes drug costs, clinical biology costs, medical and surgical intervention costs, and hospital per diem costs. Clinical events were identified in the database through their ICD-9 codes. Non-fatal events were grouped by mortality risk, which was considered as a proxy for event severity and disability level. The model does not make a distinction between costs for first-time and recurrent events. Long-term follow-up costs for potentially disabling events (IS, ICH, and HS), incurred in the outpatient setting after the initial hospitalization, were not included in the analysis because published long-term costs of stroke are scarce in Belgium and even fewer publications stratify costs according to the patient’s disability. Costs were calculated using the healthcare payer perspectiveCitation38. This perspective includes both costs borne by the national healthcare insurance and the patient (out-of-pocket payments). All costs were updated to 2012 costs using the health indexCitation39. Costs included in the model are presented in .

Table 1. Model cost inputs.

Sensitivity analyses

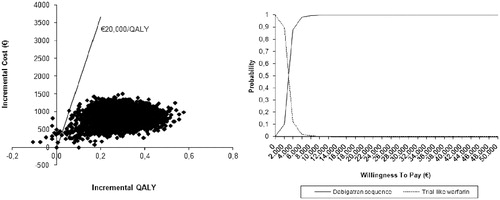

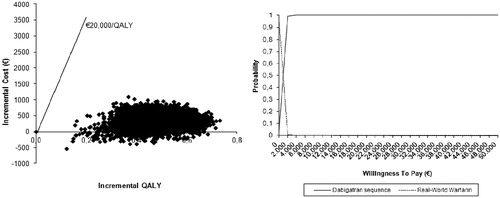

One-way sensitivity analyses were conducted on the base case model to identify parameters having a major influence on the ICER. Variations in clinical inputs, cost inputs, utility values, and time horizon were assessed. A probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) was also performed to evaluate the uncertainty around the ICERs obtained in the base case and the real-world INR control scenario. Baseline event risks and utilities were assumed to have a beta distribution and relative risks were assumed to have a log-normal distribution. Costs were assumed to have a gamma distribution. Cost-effectiveness planes and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEAC) were generated, based on 10,000 iterations.

Discounting

As recommended by the Belgian guidelines for economic evaluations, costs and outcomes are discounted by 3% and 1.5% annually, respectivelyCitation38.

Results

In the base case analysis, total costs per patient were €13,333 for dabigatran and €12,454 for warfarin (). Dabigatran is associated with a slightly higher treatment cost but with lower hospitalization costs. Total QALYs per patient were 9.51 for dabigatran and 9.19 for warfarin. The corresponding ICER was €2807/QALY. Although there is no official ICER threshold in Belgium, the base case result is well below €20,000/QALY, demonstrating that dabigatran is cost-effective.

Table 2. Results of base case and scenario analyses.

In the first scenario analysis (dabigatran vs warfarin with real-world INR control), warfarin patients with real-world INR control incurred higher costs (€12,864) and gained less QALYs (9.02) compared to warfarin patients with trial-like INR control (base case analysis). This led to a decreased ICER of €970/QALY. In the second scenario analysis (dabigatran vs warfarin, aspirin or no treatment), the total costs and the total QALYs per patient treated with warfarin, aspirin, or not treated decrease to €10,008 and 8.88, respectively, resulting in an ICER of €5296/QALY. In this scenario, despite a greater gain in QALYs compared to the base case analysis (0.63 vs 0.32), the higher incremental cost per patient of dabigatran vs low cost aspirin or no treatment results in an increase of the ICER compared to the base case analysis.

Results of the one-way sensitivity analysis are presented in the supplementary material. Three model parameters were identified as having a significant impact on the ICER of dabigatran: the cost of INR monitoring, the time horizon, and the TTR of the warfarin patients. Among the clinical input parameters, the relative risk of IS for dabigatran led to the greatest variation in the ICER. However, the ICER never exceeded €11,000/QALY utilizing the most pessimistic input parameters indicating that dabigatran remained cost-effective despite important variations in critical model input parameters. Based on the observed impact of the TTR in warfarin patients on the ICER of dabigatran, an additional analysis was performed to determine the break-even point at which dabigatran would no longer be cost-effective, i.e., the ICER would be above €20,000/QALY. This analysis indicates that a TTR between 98–99% would be required.

and present the results of the PSA for the base case analysis and the warfarin with real-world INR control scenario, respectively. If the willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold is set at €20,000/QALY, dabigatran has a probability of being cost-effective of 99.85% in the base case analysis. The probability increases to 100% when the INR control achieved with warfarin is less optimal. Even if the WTP threshold is set at a conservative value of €10,000/QALY, dabigatran still has a probability of 99.65% of being a cost-effective therapeutic alternative to warfarin (in the base case analysis).

Discussion

This analysis aimed to assess the cost-effectiveness of dabigatran in the prevention of stroke and SE in AF patients in Belgium. Dabigatran was compared to warfarin with trial-like INR control in the base case analysis and to warfarin with real-world INR control and to warfarin, aspirin, and no treatment, in two distinct scenario analyses.

In the absence of an official WTP threshold in Belgium, a WTP threshold of €20,000/QALY was used as reference. Results indicate dabigatran is cost-effective vs optimally controlled warfarin treatment (€2807/QALY) and highly cost-effective when it is compared to warfarin treatment with real-world INR control (€970/QALY). These results can be considered robust as the one-way sensitivity analyses results remained well under the threshold and the uncertainty around the ICERs observed in the PSA was minimal. Dabigatran is still cost-effective when compared to warfarin, aspirin, and no treatment simultaneously, although the ICER is slightly higher (€5296/QALY). These results are explained by the significant risk reduction in IS, ICH, and HS associated with dabigatran, resulting in longer survival, improved quality-of-life, and lower hospitalization costs. One of the strengths of the analysis was the possibility to derive clinical inputs from patient-level data from the RE-LY trial, enabling the identification of the age-specific event rates necessary to populate the sequential dosing model and the precise estimation of the relative risk of IS, an important driver of model results. The use of patient-level data from the RE-LY trial helps to improve the granularity of the model and to better assess the uncertainty surrounding the results. Another strength of the analysis was the possibility to adjust the INR control level for warfarin patients as this is a key determinant of dabigatran’s cost-effectiveness. The one-way sensitivity analysis shows that dabigatran remains cost-effective even when the TTR reaches a hypothetical value of 80%. An additional threshold analysis shows that dabigatran is cost-effective until the TTR reaches a value as high as 98%. Such high TTR values are hardly achieved in routine clinical practice.

This analysis also has some limitations. First, as in the majority of economic models, treatment benefits are assumed to remain constant over time and were extrapolated beyond the 2-year RE-LY trial period. Second, long-term costs for stroke and hemorrhagic events were not included in the model, due to the lack of published data for Belgium. Additional research on the long-term cost of IS, ICH, and HS in Belgium by severity level should be undertaken in order to complete the analysis. It must, however, be noted that the absence of long-term cost data from the analysis led to a very conservative calculation of the ICER for dabigatran: adding additional costs for the clinical events in the model would only increase the cost difference between dabigatran and its comparators, thus lowering the ICERCitation25. Third, post-event disability levels were retrieved from the RE-LY trial and from the literature and the model did not take into account a possible improvement in the patient’s functional status over time. Fourth, the treatment effect of warfarin observed in the RE-LY trial was considered to be representative for the effectiveness of acenocoumarol and phenprocoumon, which are commonly used in Belgian clinical practice. Furthermore, the cost of dabigatran treatment used in the model will have to be compared to its real-life treatment cost in routine clinical practice, once this is available. Finally, the discontinuation rate due to non-clinical reasons taken from RE-LY could also be different in the ‘real-world’ setting.

Overall the results of this analysis confirm those observed in other cost-effectiveness analyses of dabigatran using either the same modelCitation20,Citation22,Citation23 or other models based on the European label scenarioCitation21,Citation24. Dabigatran was found to be cost-effective in Canada, the UK, Denmark, and Sweden, and the Belgian analysis strengthens the convergent validity of these findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study suggests that dabigatran, a novel oral anticoagulant, is a cost-effective treatment for the prevention of stroke and SE in patients with non-valvular AF in the Belgian healthcare setting when compared to warfarin. According to this analysis, dabigatran represents good value for money for the healthcare payer in Belgium, in line with recent findings in other healthcare settings.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This project was funded by SCS Boehringer Ingelheim Comm.V.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

HW is an employee of SCS Boehringer Ingelheim Comm. VT has received travel support and speaker fees from Boehringer Ingelheim. VT and LA have provided consulting services for Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, and Pfizer on new oral anticoagulants.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (46.9 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Catherine Druez, SCS Boehringer Ingelheim Comm.V, and Brigitta Monz, Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH, for their contribution in reviewing the manuscript.

References

- Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2010;31:2369-429

- Heeringa J, van der Kuip DA, Hofman A, et al. Prevalence, incidence and lifetime risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J 2006;27:949-53

- Claes N, Van Laethem C, Goethals M, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in adults participating in a large-scale voluntary screening programme in Belgium. Acta Cardiol 2012;67:273-8

- Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, et al. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults. National implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the ATRIA Study. JAMA 2001;85:2370-5

- Rietbrock S, Heeley E, Plumb J, et al. Chronic atrial fibrillation: incidence, prevalence, and prediction of stroke using the Congestive heart failure, hypertension, age >75, diabetes mellitus, and prior Stroke or transient ischemic attack (CHADS2) risk stratification scheme. Am Heart J 2008;156:57-64

- Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation Framingham Study. Stroke 1991;22:983-8

- Frost L, Engholm G, Johnsen S, et al. Incident thromboembolism in the aorta and the renal, mesenteric, pelvic, extremity arteries after discharge from the hospital with a diagnosis of atrial fibrillation. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:272-6

- Thijs V, Dewilde S, Putman L, et al. Cost of hospitalization for cerebrovascular disorders in Belgium. Acta Neurol Belg 2011;111:104-10

- Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Atrial Fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2006;114:e257-354

- Singer DE, Albers GW, Dalen JE, et al. Antithrombotic therapy in atrial fibrillation: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest 2008;133:546-92

- Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:857-67

- van Walraven C, Jennings A, Oake N, et al. Effect of study setting on anticoagulation control: a systematic review and metaregression. Chest 2006;129:1155-66

- Dolan G, Smith LA, Collins S, et al. Effect of setting, monitoring intensity and patient experience on anticoagulation control: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:1459-72

- Claes N. Quality of oral anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation: a cross-sectional study in general practice. Eur J Gen Pract 2006;12:163-8

- Nieuwlaat R, Capucci A, Camm AJ, et al; on behalf of the Euro Heart Survey Investigators. Atrial fibrillation management: a prospective survey in ESC Member Countries. The Euro Heart Survey on Atrial Fibrillation. Eur Heart J 2005;26:2422-34

- Thijs V, Van der Niepen P, Van de Borne P, et al. Oral anticoagulant use, atrial fibrillation and CHADS2 score in primary care patients with hypertension: the Belgica-Stroke Study, 2010 (abstract and poster)

- De Breucker S, Herzog G, Pepersack T. Could geriatric characteristics explain the under-prescription of anticoagulation therapy for older patients admitted with Atrial Fibrillation? A retrospective observational study. Drugs Aging 2010;27:1-7

- Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al; the RE-LY Steering Committee and Investigators. Dabigatran versus Warfarin in patients with Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139-51

- Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulation therapy investigators. Newly identified events in the RE-LY Trial. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1875-6

- Sorensen SV, Kansal AR, Connolly S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in atrial fibrillation: a Canadian payer perspective. Thromb Haemost 2011;105:909-19

- Pink J, Lane S, Pirmohamed M, et al. Dabigatran etexilate versus warfarin in management of non-valvular atrial fibrillation in UK context: quantitative benefit-harm and economic analyses. BMJ 2011;343:d6333

- Kansal AR, Sorensen SV, Gani R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in UK patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart 2012;98:573-8

- Langkilde LK, Asmussen MB, Overgaard M. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Applying RE-LY to clinical practice in Denmark. J Med Econ 2012;15:1-9

- Davidson T, Husberg M, Janzon M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran compared with warfarin for patients with atrial fibrillation in Sweden. Eur Heart J 2013; 34(3):177-83

- Sorensen SV, Dewilde S, Singer DE, et al. Cost-effectiveness of warfarin: trial versus “real-world” stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J 2009;157:1064-73

- Roskell NS, Lip GY, Noack H, et al. Treatments for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: network meta-analyses and indirect comparisons versus dabigatran etexilate. Thromb Haemost 2010;104:1106-15

- Hylek EM, Go AS, Chang Y, et al. Effect of intensity of oral anticoagulation on stroke severity and mortality in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1019-26

- Rosand J, Eckman MH, Knudsen KA, et al. The effect of warfarin and intensity of anticoagulation on outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:880-4

- Bevolking - Sterftetafels, België 1997–2009, Statbel. Brussels: Algemene Directie Statistiek en Economische Informatie, 2011. www.statbel.fgov.be. Accessed June 8, 2011.

- Gage BF, Cardinalli AB, Owens DK. The effect of stroke and stroke prophylaxis with aspirin or warfarin on quality of life. Arch Intern Med 1996;156:1829-36

- Sullivan PW, Arant TW, Ellis SL, et al. The cost effectiveness of anticoagulation management services for patients with atrial fibrillation and at high risk of stroke in the US. Pharmacoeconomics 2006;24:1021-33

- Pradaxa. Summary of Product Characteristics. Community register of medicinal products for human use. Brussels: European Commission, 2012. http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community–register/html/h442.htm.http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/html/h442.htm Accessed July 10, 2012

- Yousef ZR, Tandy SC, Tudor V, et al. Warfarin for non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation: five year experience in a district general hospital. Heart 2004;90:1259-62

- Walker AM, Bennett D. Epidemiology and outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation in the United States. Heart Rhythm 2008;5:1365-72

- Gailly J, Gerkens S, Van Den Bruel A, et al. Use of point-of care devices in patients with oral anticoagulation: a health technology assessment. Health Technology Assessment (HTA). Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE), 2009. KCE Reports vol 117C

- Databank Farmaceutische Specialiteiten. Rijksinstituut voor Ziekte- en Invaliditeitsverzekering (RIZIV). Brussels: Rijksinstituut voor Ziekte- en Invaliditeitsverzekering, 2012. http://www.riziv.fgov.be/drug/nl/drugs/index.htm. Accessed April 20, 2012

- NomenSoft databank. Rijksinstituut voor Ziekte- en Invaliditeitsverzekering (RIZIV). Brussels: Rijksinstituut voor Ziekte- en Invaliditeitsverzekering, 2012. https://www.riziv.fgov.be/webprd/appl/pnomen/Search.aspx?lg=N.Accessed April 20, 2012

- Cleemput I, Van Wilder P, Vrijens F, et al. Guidelines for pharmacoeconomic evaluations in Belgium. Health Technology Assessment (HTA). Brussels: Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE); 2008. KCE Reports 78C

- Consumptieprijsindex vanaf 1920 en gezondheidsindex vanaf 1994. Brussels: FOD Economie, K.M.O, Middenstand en Energie, 2012. http://economie.fgov.be/nl/ modules/publications/statistiques/economie/prijzen_–consumptieprijsindex_vanaf_1920_en_ gezondheidsindex_vanaf_1994.jsp. Accessed April 20, 2012.

- Robinson A, Thomson R, Parkin D, et al. How patients with atrial fibrillation value different health outcomes: a standard gamble study. J Health Serv Res Policy 2001;6:92-8.