Abstract

Objective:

Dabigatran was the first of a new generation of anticoagulation drugs for the indication of non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF) to be approved. Evidence show that dabigatran 150 mg twice daily significantly reduces the risk of stroke and systemic embolism (RR = 0.65; p < 0.001) and shows a comparable rate of major bleedings (RR = 0.93; p = 0.32), whereas dabigatran 110 mg twice daily was associated with a comparable rate of stroke and systemic embolism (RR = 0.90; p = 0.30) and a significantly lower rate of major bleedings compared to warfarin treatment (RR = 0.80; p = 0.003). The purpose is to review current economic evaluations of these alternatives for healthcare professionals to include these findings in their decision-making.

Methods:

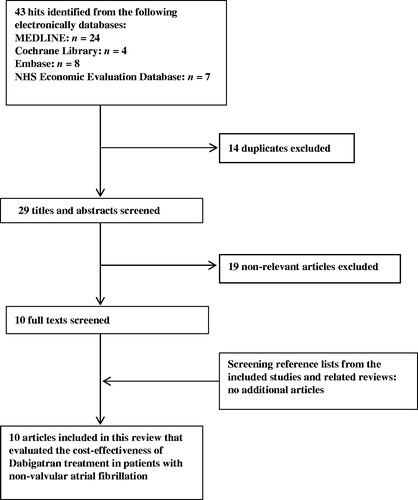

A systematic literature search identified 43 economic evaluations, of which 10 were included and evaluated according to the Consensus Health Economic Criteria list (CHEC-list) and the Oxford model.

Results:

Six economic evaluations concluded that dabigatran was a cost-effective alternative to warfarin. One evaluation concluded the same except when quality in warfarin treatment was excellent, with a mean time in therapeutic range (TTR) > 73%. Three evaluations concluded that dabigatran was a cost-effective alternative to warfarin in patient sub-groups; TTR ≤ 64%, congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75, diabetes mellitus, prior stroke or transient ischemic attack (CHADS2 score) ≥3, or a CHADS2 score = 2 unless international normalized ratio (INR) control was excellent, and with high risk of stroke or in a low-quality warfarin treatment. Dabigatran 110 mg twice daily was in general dominated by dabigatran 150 mg twice daily.

Limitations:

The evaluations were not fully homogeneous, as some did not include loss of productivity, costs of dyspepsia, and annual costs of dabigatran patient management.

Conclusions:

In the majority of the economic evaluations, dabigatran is a cost-effective alternative to warfarin treatment. In some evaluations dabigatran is only cost-effective in sub-groups, such as patients with a low TTR-value in warfarin treatment and a CHADS2 score ≥2.

Introduction

Worldwide, non-valvular atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common cardiac arrhythmia, which affects more than 6% of the population above 80 years, and increases mortality and morbidity rates due to a markedly increased risk of stroke and systemic embolismCitation1,Citation2. Such events will often result in serious consequences for the patients’ quality-of-life and significant health economic consequencesCitation3.

For more than five decades the vitamin K antagonist warfarin has been the commonly used anticoagulation treatment for this patient group, despite the fact that it has been criticised for its management disadvantages, such as regular monitoring of international normalized ratio (INR) due to a narrow therapeutic index and interactions with alcohol, food products containing high levels of K-vitamin, and other pharmaceuticalsCitation4,Citation5.

In August 2011, the direct thrombin inhibitor dabigatran achieved marketing approval in Europe as the first of a new generation of anticoagulation drugsCitation5. This approval was based on a large multinational phase III clinical trial, The Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Anticoagulant Therapy (RE-LY). This trial concluded that dabigatran 150 mg twice daily (high-dose dabigatran) significantly reduced annual risk of stroke or systemic embolism from 1.71% to 1.11% (95% CI = 0.52–0.81, p < 0.001) compared to dose-adjusted warfarin treatment and dabigatran 110 mg twice daily (low-dose dabigatran) was associated with a reduced annual risk of 1.54% (95% CI = 0.74–1.10, p = 0.30). Furthermore, low-dose dabigatran significantly reduced annual risk of major bleedings from 3.57% to 2.87% (95% CI = 0.70–0.93, p = 0.003) compared to dose-adjusted warfarin treatment and high-dose dabigatran was associated with a reduced annual risk of 3.32% (95% CI = 0.81–1.07, p = 0.32)Citation6.

Generally, dabigatran is priced at a higher level compared to warfarinCitation7. However, it is important to estimate the incremental health gain in proportion to the incremental costs, in order to evaluate whether this new treatment option is cost-effective. The decision-makers at different levels ought to take these health economic perspectives into account when evaluating dabigatran treatment. The purpose of this study is to review all current economic evaluations of dabigatran compared to warfarin treatment in patients with AF, thereby evaluating the cost-effectiveness of dabigatran treatment worldwide.

Methods

Systematic literature search

A systematic literature search was conducted on October 24, 2012 by the authors Louise Justesen Hesselbjerg and Heidi Sjoelund Pedersen. This was completed in order to identify relevant economic evaluations of dabigatran and warfarin treatment in the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with AF. The literature search was conducted in the following databases: MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Library, and NHS Economic Evaluation Database.

Because the RE-LY trial was completed in 2009, an inclusion criterion was set to publications between 2009–2012. Other inclusion criteria were one of the following types of publications: journal articles, multi-centre studies, reviews, systematic reviews, Cochrane reviews, economical evaluations, or comparative studies. Keywords searched for in combination were: cost-effectiveness, atrial fibrillation, dabigatran, and warfarin. The exclusion criterion was economic evaluations of the indication hip and knee replacement surgery.

All identified articles were evaluated by means of the title and abstract. The full-texts of the relevant economic evaluations were then screened and the reference lists checked in order to ensure that no relevant evaluations were disregarded.

Quality assessment

The quality of the relevant economic evaluations was assessed applying the Consensus Health Economic Criteria list (CHEC-list) and their level of evidence was stated according to the Oxford model from the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based MedicineCitation8,Citation9. This quality assessment was completed by Louise Justesen Hesselbjerg and Heidi Sjoelund Pedersen. Items in the CHEC-list were evaluated with the criteria; ‘Yes’ indicating that the item was adequately covered or reported in an appropriate way, or ‘No’ indicating that the item was not met. The 19th item, ‘Are ethical and distributional issues discussed appropriately?’, was irrelevant in this review and therefore excludedCitation8. Evaluations that achieved a higher score than 75% were defined as high-quality evaluations, >50–≤75% were defined as moderate-quality evaluations, and ≤50% were defined as low-quality evaluationsCitation10. Evaluations with a low-quality were excluded. Furthermore, each evaluation was assigned a number according to the Oxford model of 1a–1c, 2a–2c, 3a–3b, 4, or 5, with 1a being of highest level of evidenceCitation9. Disagreements between the authors assessing the quality were resolved through discussion, which is illustrated in .

Table 1. Summed quality scores according to the CHEC-list and the level of evidence according to the Oxford model of included economic evaluations of dabigatran and warfarin treatment in the prevention of apoplexia and systemic embolism in patients with AF.

Results

Systematic literature search

The systematic literature search resulted in 43 hits, of which 14 were duplicates and 19 evaluations were excluded after screening of titles and abstracts. Ten remaining economic evaluations were included after full-text reviewing and the reference lists did not yield any additional relevant literature. Thereby, 10 economic evaluations were included in this reviewCitation11–20, which is illustrated in .

Quality assessment

On average 89.9% of the criteria were met in the CHEC-list, ranging from 77.8–94.4%. Some of the factors not included were; annual costs of dabigatran patient management, loss of productivity, discussing generalizability, a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), and indicating a potential conflict of interests. Furthermore, health outcomes were in general obtained from a single clinical trial. As no evaluations obtained a score below 75%, they were all evaluated as high-quality evaluations. All economic evaluations were assigned the level of evidence 2b, which corresponds to ‘An analysis based on clinically sensible costs or alternatives; limited review(s) of the evidence, or single studies; and including multi-way sensitivity analyses’Citation9, which is illustrated in .

Model characteristics

Of the 10 economic evaluations, three were published in 2011Citation1Citation4,Citation15,Citation18 and seven were published in 2012Citation11–13,Citation16,Citation17,Citation19,Citation20. The study design was in all evaluations based on Markov models with varying hypothetical cohorts of patients with AF. In the evaluations warfarin and dabigatran treatment were defined differently. In some of the Markov models dabigatran treatment was divided into sequentially/adjusted drug doses, changing drug dose from 150 mg to 110 mg twice daily at the age of 80Citation1Citation5,Citation18,Citation19. In one of the Markov models warfarin treatment was incorporated as genotype-guided anticoagulation care (genotype-guided AC)Citation12. Furthermore, in some of the Markov models warfarin treatment was incorporated as a ‘real world scenario’ including acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel, and no treatment, or as ‘trial like scenario’ including the mean TTR-value from the RE-LY trialCitation11–14,Citation16,Citation17,Citation20. The costs, adverse events, annual discount rates, and time horizons varied between the evaluations and only some of the evaluationsCitation15–17 included costs of general practitioners, proton pump inhibitors for treating dyspepsia, outpatient visits, and dabigatran patient management. None of the economic evaluations included all relevant adverse events. Some evaluations did not include outcomes such as deathCitation15, dyspepsiaCitation13–20, and systemic embolismCitation13,Citation14,Citation16,Citation17,Citation20. The annual discount rate of the evaluations varied (2–5%) as well as the time horizon, which was, e.g., stated as lifetime (maximum life expectancy 100 years), mean remaining life years (e.g., 20 years), or simply as expected lifetime without further explanation. All model characteristics of the economic evaluations are illustrated in .

Table 2. General characteristics of the included economic evaluations on dabigatran and warfarin treatment in prevention of apoplexia and systemic embolism in patients with AF.

All evaluations stated health outcomes in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). The willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold for a QALY varied significantly between the countries, in which the economic evaluations were published, from £20,000 in the UKCitation15 to €50,000 in SwedenCitation17. In all evaluations one-way sensitivity analyses were applied, of which five additionally applied multi-way sensitivity analysesCitation11,Citation12,Citation15,Citation16,Citation18. In eight of the evaluations a PSA was conductedCitation12–15,Citation17–20. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), the WTP thresholds, and choice of sensitivity analysis of each economic evaluation are illustrated in .

Table 3. Results of the included economic evaluations of dabigatran and warfarin treatment in the prevention of apoplexia and systemic embolism in patients with AF.

Results on the economic evaluations

In all of the economic evaluations dabigatran was associated with higher cost than warfarin treatment but provided higher amounts of QALYsCitation11–20. This was also the case when dabigatran was compared to acetylsalicylic acidCitation13. The real cost drivers and creators of health gain were degree of INR-controlCitation13–17,Citation20, cost of recurrent stroke and/or intracranial haemorrhage (ICH)Citation11,Citation16,Citation19, cost of bleedingsCitation11,Citation16, CHADS2 scoresCitation17, reduction of stroke riskCitation20, haemorrhage ratesCitation11, cost associated with INR-measurementsCitation13,Citation14,Citation20, difference in relative risk of stroke between dabigatran and warfarinCitation13,Citation14,Citation17,Citation19, cost of long-term follow-up care for patients with disabilitiesCitation13,Citation14, overall utility rates of IS, ICH, and HS of dabigatran in proportion to warfarin treatmentCitation13,Citation15,Citation18,Citation19, ageCitation18,Citation19, TTRCitation19, cost of dabigatran and warfarinCitation11,Citation18, utility of dabigatran and warfarinCitation12,Citation18, costs after ICHCitation18, deathCitation15, average TTR in genotype-guided ACCitation12, risk of stroke with dabigatran 150 mg vs warfarinCitation12, and stroke rateCitation11,Citation12. Of other key parameters affecting the ICERs were time horizonCitation13,Citation14,Citation20, discount ratesCitation16,Citation17, and analysis perspectiveCitation20. Langkilde et al.Citation16 calculated the ICER of high-dose dabigatran as below the Danish WTP threshold of €30,000 per QALY gained, which thereby was considered a cost-effective alternative to warfarin. The higher the level of stroke risk the more cost-effective dabigatran was compared to warfarin treatment. The calculations were in general evaluated as robust to all changes in parametersCitation16. Davidson et al.Citation17 calculated the ICER of dabigatran as far below the Swedish WTP threshold of €50,000 per QALY gained, thereby cost-effective compared to warfarin treatment. When compared to high-quality warfarin treatment the ICER increased, but was still far below WTP threshold. When taking all parameter uncertainties into account dabigatran was cost-effective in all cases, but the cost-effectiveness was largest at high risk of stroke, with a congestive heart failure, hypertension, age >75, diabetes mellitus, and prior stroke or transient ischemic attack score (CHADS2 score) = 3–6Citation17. González-Juanatey et al.Citation20 calculated the ICER of dabigatran compared to warfarin and the ICER of dabigatran treatment compared to prescribing pattern in clinical practice as below the Spanish WTP threshold of €30,000 per QALY gained. Considering all parameter uncertainties dabigatran was cost-effective in 96.4% and 99.9% of cases compared to warfarin and prescribing pattern in clinical practice, respectivelyCitation20. Sorensen et al.Citation14 calculated the ICER of dabigatran treatment compared to trial-like scenario as below the Canadian WTP threshold of $30,000 per QALY gained and the ICER of dabigatran treatment compared to real-world scenario below the same WTP threshold. Including all parameter uncertainties dabigatran was cost-effective in 82% of cases compared to the trial-like scenario, and in 99% of cases compared to the real-world scenarioCitation14. Kansal et al.Citation13 calculated the ICER of dabigatran treatment compared to warfarin treatment as below the English WTP threshold of £20,000–£30,000 per QALY gained at age <80 and age ≥80. Dabigatran was cost-effective in 98% of cases for patients aged <80 compared to warfarin, and in 63% of cases in patients aged ≥80Citation1Citation3. Kamel et al.Citation19 showed that high-dose dabigatran was likely to be a cost-effective alternative to warfarin, as the calculated ICER was below the American WTP threshold of $50,000 per QALY gained. Dabigatran was less likely to be cost-effective in patients with a high-qualitywarfarin treatment, with a mean time in therapeutic range (TTR) >73%. Taking all parameter uncertainties into account high-dose dabigatran was cost-effective in 57% of casesCitation19. Freeman et al.Citation18 calculated the ICER of high-dose dabigatran as below the American WTP threshold of $50,000 per QALY gained, thereby cost-effective compared to warfarin treatment. The cost-effectiveness of dabigatran treatment was highly dependent on the pricing of dabigatran. When the price of high-dose dabigatran exceeded $13.70 per day or the price of low-dose dabigatran exceeded $9.36 per day, then dabigatran was no longer cost-effective. As the daily drug price included in the model was $13.00 for high-dose dabigatran and $9.50 for low-dose dabigatran, only a small change in drug price would influence the cost-effectiveness of dabigatran. When taking all parameter uncertainties into account high-dose dabigatran was cost-effective in 53% of cases, and low-dose dabigatran was cost-effective in 30% of casesCitation18. Pink et al.Citation15 calculated the ICER of high-dose dabigatran to £23,082 per QALY gained, which was above the lowest English WTP threshold, but still below 30,000 per QALY gained, ranging from £20,000–30,000 per QALY gained. Thereby, high-dose dabigatran was only considered cost-effective for patients with a high risk of stroke, CHADS2 score ≥3, or in a warfarin treatment, with a TTR ≤65.5%. Combining all parameter uncertainties, warfarin was most probable to be cost-effective at WTP thresholds of £24,400 per QALY gained or lower. Low-dose dabigatran was dominated by high-dose dabigatran and both drug doses were associated with a positive incremental QALY gain compared to warfarin treatment of 86% and 94%, respectivelyCitation15. Shah and GageCitation11 calculated the ICER of high-dose dabigatran and low-dose dabigatran compared to warfarin treatment to be well above the American WTP threshold of $50,000 per QALY gained, thereby not cost-effective, but both high-dose and low-dose dabigatran treatment gained higher QALYs than warfarin, with an incremental QALY gain of 0.25 and 0.14, respectively. The calculated ICER of high-dose and low-dose dabigatran compared to acetylsalicylic acid were neither below the American WTP threshold of $50,000 per QALY gained, and thereby not cost-effective, but both high-dose and low-dose dabigatran gained higher QALYs than acetylsalicylic acid, with an incremental QALY gain of 0.48 and 0.37, respectively. If the cost of dabigatran did not exceed $1800 per year, dabigatran treatment would have been cost-effective in all cases. High-dose dabigatran is cost-effective compared to warfarin in patients with a CHADS2 score ≥2 if annual risk of haemorrhage is >6%, for patients with a CHADS2 score ≥2 if TTR <57.1%, and in patients with a CHADS2 score ≥3 unless TTR >72.6%Citation11. You et al.Citation12 calculated the ICER of high-dose dabigatran as below the Chinese WTP threshold of $50,000 per QALY gained compared to genotype-guided AC, and high-dose dabigatran dominated low-dose dabigatran. High-dose dabigatran was significantly more costly (p < 0.001), mean difference $10,416, and gained significantly higher QALYs (p < 0.001), mean difference 0.217 QALYs, than genotype-guided AC. Taking all parameter uncertainties into account, high-dose dabigatran was cost-effective in 51.6% of cases compared to genotype-guided AC. The probability of genotype-guided AC to dominate high-dose dabigatran increased at TTR ≥77% and if QALYs gained in both treatment groups were comparableCitation12. All calculated ICERs and results of sensitivity analysis are illustrated in .

Discussion

Quality assessment

The quality of the economic evaluations was assessed as high, yet some quality items were not met. None of the evaluations included all relevant costs and two evaluationsCitation12,Citation19 did not state a potential conflict of interest, which results in a low transparency. Four evaluationsCitation12,Citation14,Citation15,Citation18 did not compare their findings to other studies, thus they appeared less generalizable. Two evaluations did not apply a PSACitation11,Citation16, thereby not estimating the probability of cost-effectiveness when including all parameter uncertainties. All evaluations were assigned the evidence level 2b, which indicates a high level of evidence, thereby this review is a level 2a review. The quality assessment score and estimated level of evidence of each economic evaluation are illustrated in .

Model characteristics

It was not possible to fully compare the evaluations, as the results were calculated on the basis of varying alternative treatment approaches, and thereby they were not fully homogeneous. It might be more accurate to compare dabigatran treatment to the actual prescribing pattern of warfarin in clinical practice, as the treatment quality in a trial setting might be higher than in clinical practice due to a higher degree of monitoring.

Furthermore, variations in included costs, adverse events, annual discount rates, time horizons, and WTP thresholds contributed to a decrease in homogeneity, which makes it impossible to directly compare the ICERs of the evaluations. The fact that different health outcomes and costs were included in the Markov models might imply that incorrect estimates have been made in some of the evaluations, which would decrease the validity of the evaluations in question. Despite these variations in estimates the difference in gained QALYs between dabigatran and warfarin treatment seemed the same in the evaluations, which is illustrated in . The explanation might be that most QALY gains were calculated on the basis of the average rates of efficiency and adverse events in the RE-LY trial. Thereby, it can be questioned whether calculating the amount of QALYs on the basis of health rates from each country in question, rather than on the basis of rates from a trial covering 44 countries, would have provided more accurate results of the cost-effectiveness.

The evaluations by Shah and GageCitation11 and Langkilde et al.Citation16 were the only ones not applying a PSA, which is against the recommendations by the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE)Citation21. Thereby the probability of cost-effectiveness is not calculated, including all parameter uncertainties. Additionally, NICE recommends to include a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve every time the cost-effectiveness of two or more alternatives are comparedCitation21, which was not included in the evaluations by Davidson et al.Citation17 and Kamel et al.Citation19. Thereby, it was not possible to estimate probabilities of cost-effectiveness at different WTP thresholds.

Strengths and limitations

The quality and level of evidence of the included evaluations were assessed ensuring a high-quality review. The low homogeneity due to, e.g., different costs and adverse events made it difficult to fully compare the evaluations.

Maybe it should be considered whether the best available treatment alternatives were compared in the RE-LY trial as self-monitored warfarin treatment might be superior to common warfarin treatment. This is relevant to consider in economic evaluations. Furthermore, the up-coming anticoagulation drugs rivaroxaban and apixaban ought to be considered in future research.

Conclusions

Dabigatran is likely to be a cost-effective alternative to warfarin treatment in Denmark, the UK, Sweden, Spain, and the US. In some countries dabigatran is only cost-effective in sub-groups, such as patients in low quality warfarin treatment and high risk group of stroke. Thereby, the healthcare professionals can take this knowledge into account making decisions in clinical practice regarding dabigatran and warfarin treatment.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The study was supported by Danish Center for Healthcare Improvements, Faculty of Social Sciences and Faculty of Health Sciences, Aalborg University, Denmark.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

MBA is an employee at Boehringer Ingelheim Denmark which holds marketing approval of dabigatran, and he is co-author of one of the economic evaluations included. The other authors declare no conflicts. The study was kept objective by all authors and there were no restrictions placed on the material presented in the paper.

Acknowledgements

There is no non-author assistance to be stated.

References

- Brandes A. Behandling af atrieflimren. Rationel Farmakologi Månedsblad, 2008. http://www.irf.dk/dk/publikationer/rationel_farmakoterapi/maanedsblad/2008/behandling_af_atrieflimren.htm. Accessed October 2, 2012

- Lip GYH, Tse HF, Lane DA. Atrial fibrillation. Lancet 2012;379:648-61

- Working Party of Dansk Selskab for Apopleksi. Referenceprogram for behandling af patienter med apopleksi. Copenhagen: Dansk selskab for Apopleksi, 2009

- Boos CJ, More RS. Current controlled trials in anticoagulation for non-valvular atrial aibrillation – towards a new beginning with ximelagatran. Curr Contr Trials Cardiovasc Med 2004;5:1-7

- Schwartz NE, Albers GW. Dabigatran challenges warfarin’s superiority for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Stroke; J Cerebral Circulation 2010;41:1307-9

- Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus Warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Eng J Med 2009;361:1139-202

- Lægemiddelstyrelsen. Trends i salget af apoteksforbeholdt medicin – Udviklingen i 4. kvartal 2011. 2012. http://www.ssi.dk/Sundhedsdataogit/Analyser%20og%20rapporter/Trends%20i%20salget%20af%20apoteksforbeholdt%20medicin/∼/media/Indhold/DK%20-%20dansk/Sundhedsdata%20og%20it/NSF/Analyser%20og%20rapporter/Trends%20i%20salget%20af%20apoteksforbeholdt%20medicin/4_2011.ashx. Accessed December 6, 2012

- Evers S, Goossens M, De Vet H, et al. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: Consensus. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005;21:240-5

- Phillip B, Ball C, Badenoch D, et al. Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine - Levels of Evidence (March 2009). Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine 2009. http://www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=1025. Accessed December 6, 2012

- Hamberg-van Reenen HH, Proper KI, Van den Berg M. Worksite mental health interventions: a systematic review of economic evaluations. Occup Environ Med 2012; published online 3 August 2012, doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-100668

- Shah SV, Gage BF. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran for stroke prophylaxis in atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2011, published online 4 March 2011;123:2562-70

- You JHS, Tsui KKN, Wong RSM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran versus genotype-guided management of warfarin therapy for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation. PloS One 2012;7:e39640

- Kansal AR, Sorensen SV, Gani R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in UK patients with atrial fibrillation. Heart 2012;98:573-8

- Sorensen SV, Kansal AR, Connolly S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in atrial fibrillation: a Canadian payer perspective. Thromb Haemostasis 2011;106:753-992

- Pink J, Lane S, Pirmohamed M, et al. Dabigatran etexilate versus warfarin in management of non-valvular atrial fibrillation in UK context: quantitative benefit-harm and economic analyses. Br Med J 2011;343:d6333

- Langkilde LK, Bergholdt Asmussen M, Overgaard M. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran etexilate for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation. Applying RE-LY to clinical practice in Denmark. J Med Econ 2012;15:695-703

- Davidson T, Husberg M, Janzon M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran compared with warfarin for patients with atrial fibrillation in Sweden. Eur Heart J 2012;34:177-83

- Freeman JV, Zhu RP, Owens DK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med 2011;154:1-11

- Kamel H, Johnston SC, Easton JD, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran compared with warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with atrial fibrillation and prior stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke J Cerebral Circulation 2012;43:881-3

- González-Juanatey JR, Álvarez-Sabin J, Lobos JM, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dabigatran for stroke prevention in non-valvular atrial fibrillation in Spain. Rev Esp Cardiol (English Edition) 2012;65:901-10

- Claxton K, Sculpher M, McCabe C, et al. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis for NICE technology assessment: not an optional extra. Health Econ 2005;14:339-47