Abstract

Background:

Although chronic migraine is associated with substantial disability and costs, few treatments have been shown to be effective. OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox, Allergan Inc., Irvine, CA) is the first treatment to be licensed in the UK for the prophylaxis of headaches in adults with chronic migraine. This study aims to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA in this indication in the UK.

Methods:

A state-transition (Markov) model was developed comparing onabotulinumtoxinA to placebo. Efficacy data and utility values were taken from the pooled Phase III REsearch Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy (PREEMPT) clinical trials program (n = 1384). Estimates of resource utilisation were taken from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS), and stopping rules were informed by published medical guidelines and clinical data. This study estimated 2-year discounted costs and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) from the UK National Health Service perspective.

Results:

At 2 years, treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA was associated with an increase in costs of £1367 and an increase in QALYs of 0.1 compared to placebo, resulting in an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of £15,028. Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA reduced headache days by an estimated 38 days per year at a cost of £18 per headache day avoided. Sensitivity analysis showed that utility values had the greatest influence on model results. The ICER remained cost-effective at a willingness to pay threshold of £20,000–£30,000/QALY in the majority of scenario analyses as well as in probabilistic sensitivity analysis, where onabotulinumtoxinA was cost-effective on 96% of occasions at a threshold of £20,000/QALY and 98% of occasions at £30,000/QALY.

Conclusion:

OnabotulinumtoxinA has been shown to reduce the frequency of headaches in patients with chronic migraine and can be considered a cost-effective use of resources in the UK National Health Service. The uncertainties in the model relate to the extrapolation of clinical data beyond the 56-week trial.

Introduction

Migraine is a debilitating, chronic, neurological disorder characterised by attacks of moderate-to-severe head pain accompanied by nausea, photophobia, phonophobia, and visual disturbances in various combinationsCitation1. Chronic migraine is classified as a complication of migraine according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edition revised criteria (ICHD-2R). It is characterised by headache occurring on 15 or more days per 28 days for at least 3 months with 8 or more days meeting criteria for migraine or responding to migraine-specific medication, in the absence of medication over-useCitation2. Chronic migraine is estimated to affect 1.6% of the adult populationCitation3, and usually arises as a complication of episodic migraine (characterised by headache on <15 days per 28 days)Citation4. Overall, compared to those with episodic migraine, people with chronic migraine experience significantly greater disability as well as higher rates of acute medication use, physician visits, hospitalisations and emergency department visits, along with a significant reduction in workplace productivityCitation5,Citation6.

In the UK, topiramate and onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox, Allergan Inc., Irvine, CA) are the only licensed drugs for the prophylactic treatment of migraine. Topiramate is indicated for migraine in general, and onabotulinumtoxinA is indicated specifically for prophylactic use in adults with chronic migraine. Other preventive medications (including beta-blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, and anti-epileptics) are frequently prescribed off-label as a first-line treatmentCitation7–9. While effective for some patients, oral prophylactics (including topiramate) are associated with side-effects and modest adherence ratesCitation10,Citation11.

The primary evidence supporting the use of onabotulinumtoxinA in chronic migraine comes from two large clinical trials, reported separately and in pooled analysesCitation12–14. The Phase III REsearch Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy (PREEMPT) program (n = 1384) was designed as two multi-centre studies, each with a 24-week, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled phase followed by a 32-week open-label phase. On average the chronic migraine patients enrolled into the PREEMPT trials had 19.9 headache days per 28 days at baseline and had experienced ∼20 years of frequent headaches. The pooled trial population had a mean age of 41.3 and was predominantly female (86.4%) and Caucasian (90.1%), consistent with known demographics of the overall population of chronic migraine patientsCitation15. At week 24, patients randomised to onabotulinumtoxinA experienced a greater reduction in headache days per 28 days than those randomised to placebo (−8.4 vs −6.6, p < 0.001). Statistically significant improvements also were observed in overall health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL), as measured by the Migraine Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire v2.1 (MSQ) and the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6™) questionnaireCitation16–18. The HIT-6 is a 6-item questionnaire, and measures the impact of headaches specifically. The MSQ, however, contains broader questions about the impact of migraine on daily life, and has similarities enabling a mapping to be performed to the European Quality of Life-5 Dimension (EQ-5D). The discontinuation rate attributed to adverse events was low (3.8% onabotulinumtoxinA vs 1.2% placebo). Adverse events were generally mild-to-moderate in severity, short-lived, and consistent with the known safety and tolerability profile of onabotulinumtoxinACitation18.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA compared with placebo for the prophylaxis of headaches in adults with chronic migraine from the perspective of the UK National Health Service (NHS).

Methods

A Markov model was developed to estimate incremental costs per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) associated with onabotulinumtoxinA compared to placebo using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Redmond, WA). A 2-year time horizon with a cycle length of 12 weeks was employed. This cycle length was chosen to reflect the 12-week intervals between onabotulinumtoxinA treatments in the PREEMPT trials. Efficacy data to inform patient transitions were taken from a post-hoc analysis of the pooled data from the PREEMPT program.

Patient population

Analyses are presented for three patient populations:

The licensed population, of all chronic migraine patients.

Patients who have previously received one or more oral prophylactic treatments (as there is currently only one other licensed treatment for migraine).

Patients who have previously received three or more oral prophylactic treatments (as considered by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)Citation19).

In the 1384 patients in the PREEMPT program, approximately two-thirds (983/1384) had received prior prophylaxis and one-third (439/1384) had previously received three or more prior prophylaxis treatments. Efficacy and HRQoL values were taken from the clinical trial specifically for each of these patient groups by analysis of the patient-level data performed on behalf of the authors by Allergan, Inc.

Comparator

The standard of care for patients with chronic migraine is poorly defined. While several oral medications are used for headache prophylaxis, onabotulinumtoxinA is the only pharmacotherapy specifically licensed for prophylaxis of headache in chronic migraineCitation20. A systematic literature search of potential comparators found insufficient data to support an indirect comparison, or to directly populate the specific health states employed in this model. One small pilot study was identified that evaluated onabotulinumtoxinA compared to topiramate in a patient population naïve to both treatments; however, this presented insufficient detail to populate the modelCitation21.

In the PREEMPT clinical trials, patients were treated with either onabotulinumtoxinA or a series of injections of saline solution in a fixed paradigm. As no established standard of care exists and PREEMPT patients were permitted to take their usual acute headache medications, placebo treatment is considered as the comparator in the model and assumed to represent consultant appointments to tailor acute medication, such as triptans. Because the placebo injections were associated with a striking reduction in headache days, this comparator is considered conservative (see Discussion).

Model structure

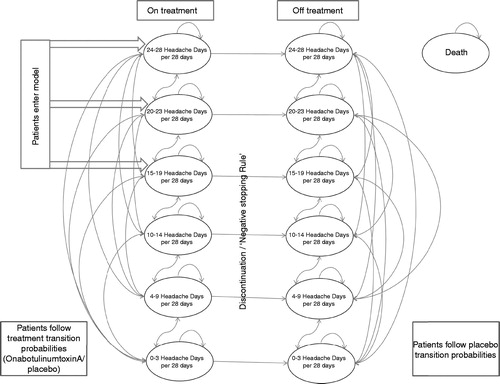

The model comprised 13 health states, including death, an absorbing state. The remaining 12 states were split into two parallel stages: on treatment and off treatment. Each treatment state was sub-divided into categories based on the number of headache days per 28 days. Within each set of six, three health states represented headache frequencies classified as episodic migraine (0–3, 4–9, and 10–14 headache days per 28 days), and three health states represented headache frequencies classified as chronic migraine (15–19, 20–23, and 24+ headache days per 28 days) ()Citation22. These health states were chosen because prophylaxis is not indicated for 0–3 migraines per 28 days, and those having 10–14 migraines are seen as being in danger of transitioning to chronic migraineCitation4,Citation23. Within chronic migraine no sub-classification of patients exists, therefore three health states were assumed, based on dividing the patients at baseline of the PREEMPT trials into equal proportions. These health states then allowed for patients to improve the number of headache days per 28 days, whilst remaining in chronic migraine.

Patients were distributed among health states at baseline in the model in the same proportion as at baseline in PREEMPT. At baseline, all patients were in one of the chronic migraine health states as required by the protocol. Death rates were taken from the UK Office of National Statistics Interim Life Tables for England and Wales (2008–2010)Citation24, with death rates used for a cohort matching the patient population in the PREEMPT study (aged 42, 87.5% female). Given the relatively young age of the population and short time horizon, the inclusion of mortality has only a small impact on the results.

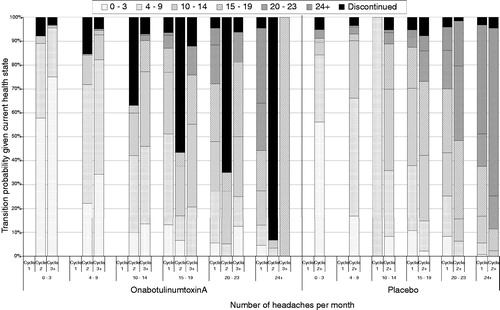

Patients were assumed to transition between health states at the beginning of each new 12-week cycle, based on the observed transitions in PREEMPT. The results seen in PREEMPT indicate that patients experience a large fall in the number of days per 28 days experienced in cycle 1 (both placebo and onabotulinumtoxinA), which is not repeated in subsequent cycles. Cycle 1 data are, therefore, used independently. Following this, one cycle (weeks 12–24) of placebo data is available, which is used as the transition matrix beyond cycle 1 for placebo. For onabotulinumtoxinA, four cycles of data are available (weeks 12–24, weeks 24–36, weeks 36–48, and weeks 48–56). The data from these cycles are combined and used for all cycles beyond the first cycle. The resulting transition probabilities are shown visually in , divided by treatment arm, and model cycle—the large number of discontinuations in cycle 2 of the onabotulinumtoxinA arm is due to the negative stopping rule, which moves patients who have had an inadequate response off treatment.

When patients discontinued (in either the onabotulinumtoxinA or placebo arm), they transitioned between health states in the off-treatment segment of the model. Following treatment discontinuation, they received placebo transition probabilities and placebo utility values, in addition to costs determined by their health state (linked to the level of resource consumption). They are assumed to have no neurologist visits or treatment costs.

Negative stopping rule

Neurologists advised that patients discontinue treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA if they did not have a sufficient reduction in the number of headaches experienced, and considered a 30% reduction within the first two cycles to be clinically relevant. To capture this, a ‘negative stopping rule’ was applied in the model, whereby patients discontinued treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA if their number of headache days per 28 days did not decrease by at least 30% in the first two cycles of treatment. These were implemented by using additional programming on the patient-level data to determine which patients had a ‘successful’ response, with those that did not then classified as discontinuers. The impact of this negative stopping rule was varied in sensitivity analysis.

Positive stopping rule

In a separate prospective observational study of onabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of chronic migraine which followed patients for at least 2 years, 24% of subjects were able to stop treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA and remain largely headache-free for at least 6 monthsCitation25. To capture this, a ‘positive stopping rule’ was applied.

In the model, after the first year of treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA, patients were categorised as experiencing episodic migraine (health states 0–3, 4–9, and 10–14 headache days) or chronic migraine (health states 15–20, 20–23, and 24+ headache days). Twenty-four per cent of the episodic patients were then assumed to cease treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA due to this ‘positive stopping rule’. These patients remained in the health state in which they were at the end of Year 1 (through the use of an identity matrix) until the end of Year 2, and had the utility values associated with onabotulinumtoxinA treatment and the costs associated with placebo. The identity matrix consists of a table where the probability of moving is set to 0 in all possibilities, except for the probability of remaining in the same state. Beyond Year 2 (as used in sensitivity analyses), placebo utility values and transition probabilities were automatically applied to the patients who had discontinued treatment due to the negative stopping rule.

Health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL)

In PREEMPT, the MSQ was used to collect HRQoL information, using a published mapping algorithm to the EQ-5DCitation26. The raw MSQ scores from the clinical studies were mapped to the EQ-5D to produce utility values between 0–1 for both onabotulinumtoxinA and placebo arms separatelyCitation26. The resulting utility values were generally higher in each health state for patients treated with onabotulinumtoxinA ().

Table 1. Utility values for onabotulinumtoxinA and placebo across health states and patient populations.

Although the health states are defined by the number of headache days (defined as a day with a headache lasting for at least 4 h) per 28 days, quality-of-life is also related to the severity and frequency of headaches. If a treatment results in a reduction from severe to moderate headache or a reduction in hours of pain that does not cross the 4-h barrier, then this will not be captured in the headache days measure alone. In the PREEMPT studies, when compared to the placebo group, the onabotulinumtoxinA group showed substantial reductions in the frequency of moderate or severe headache days per 28 days as well as the cumulative hours of headache on headache days. In this way, the measurement of HRQoL through the MSQ (and the utility values derived from it) may have greater sensitivity in capturing the benefits of treatment than considering headache days alone. The resulting values are shown in , which shows the utility values used in the model by treatment arm, and number of prior therapies.

In sensitivity analysis, a scenario was considered where the placebo and onabotulinumtoxinA utility values were pooled for each health state. As a result, no HRQoL benefit from treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA was assumed beyond the impact on the number of headache days per 28 days.

Healthcare resource use and costs

Following the injection paradigm in PREEMPT, patients in the onabotulinumtoxinA arm received 155–195 Units of onabotulinumtoxinA in each 12-week cycle (mean 164 Units). The cost assumed for onabotulinumtoxinA was therefore one 200-Unit vial (£276.40)Citation27, 30 min of consultant time (to take the patient history, tailor prophylactic and acute treatment), and 15 min of consultant time to administer the injections. There were no drug costs associated with placebo treatment, but patients were assumed to have one 30-min appointment with a consultant in each 12-week cycleCitation28. The cost of consultant time was assumed to be £146 per hourCitation28.

Each health state was associated with a cost of care, consisting of general practitioner (GP) visits (£32.00Citation28), emergency department (ED) visits (£77.33Citation29), hospitalisations (£583.67Citation29), and triptan costs (£3.35Citation27). The resource use was informed by data from the UK patients in the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS)Citation5, with unit costs taken from the NHS reference costs 2010Citation29. The cost of triptans per attack was based on the weighted average of triptan costs in the UK in 2010, taken from NHS Prescriptions Cost AnalysisCitation30. The mean per-cycle cost associated with each health state was calculated by multiplying the mean healthcare resource utilisation for each health state by the cost of each resource ().

Table 2. Resource use and costs by health state (per 12-week model cycle).

Perspective

The analysis was conducted from the perspective of the NHS. All relevant costs of chronic migraine were considered, including acute headache treatment medications, accident and emergency visits, hospital stays, physician/neurologist visits, cost of onabotulinumtoxinA, and costs of administering onabotulinumtoxinA or placebo. All analyses excluded patients’ out-of-pocket expenses and caregiver costs. Following UK methodology recommendations, future costs and QALYs were discounted at an annual rate of 3.5%Citation31. The base year for calculations was 2010; the latest year for which NHS Reference Costs were available.

A scenario analysis was performed which included costs from a societal perspective. In this scenario, the cost of lost productivity was included in calculations, in addition to healthcare costs. Data on the number of hours lost in each health state due to migraine were taken from the IBMS study. It was then assumed that a full-time day is 8 h (4 h for part-time workers), which was then multiplied by the average wage for UK employees (based on the demographics of the PREEMPT study) taken from the Office of National Statistics Annual Survey of Hours and EarningsCitation32.

Sensitivity analyses

Parameter uncertainty was tested using scenario analysis and probabilistic sensitivity analysis. Scenario analysis was conducted by varying the assumptions around the administration costs, stopping rules, time horizon, and utility scores. In probabilistic analysis, values were randomly sampled from the 95% confidence interval for all parameters (except drug costs), taken from the source publication. Five thousand simulations were performed.

Results

Base case

In the licensed population, over a 108-week (∼2 year) time horizon of nine cycles, and assuming the inclusion of both a negative and a positive stopping rule, treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA was associated with an increase in costs of £1367 (£3077 vs £1680) and increase in discounted QALYs gained (1.30 vs 1.20) compared to placebo. This resulted in an Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) of £15,028 per QALY gained. Treatment with onabotulinumtoxinA reduced headache days by an estimated 38 days per year, at a cost of ∼£18 per headache day avoided. Over the 108-week horizon, onabotulinumtoxinA increased drug and administration costs by £1488 compared to placebo. However, this increased cost was partially offset by a reduction in the costs of hospitalisations and other resource use; the disaggregated results are shown in .

Table 3. Base case results—disaggregated costs and QALYs.

In the secondary analyses, for both the sub-group of subjects who had received one or more prior treatments and the sub-group of subjects who had received three or more prior treatments, onabotulinumtoxinA remained cost-effective, with ICERs of £14,273 and £17,212 (). These small changes in the ICER are driven by small changes in patient transition probabilities, leading to differences in the predicted costs and QALY gains of treatment.

Table 4. Base case results and sensitivity analyses.

Scenario analyses

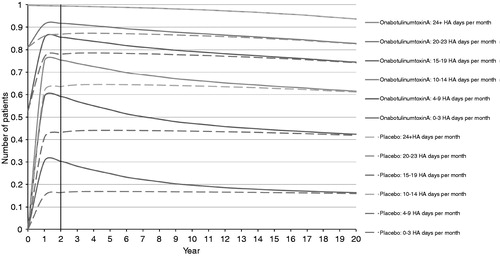

Varying the time horizon between 24 weeks and 20 years changes the ICER dramatically. If the time horizon is extended to 10 years, the ICER decreases to £10,765, and extending the time horizon to 20 years further decreases the ICER to £9762. Using a 2-year horizon in the model, at the end of the period onabotulinumtoxinA patients are generally in better health states, with fewer headache days than placebo patients. Although the majority of onabotulinumtoxinA patients have discontinued onabotulinumtoxinA at this point, patients have discontinued in better health states, having an average of 8.8 headache days per 28 days, compared to 12.2 headache days on placebo.

Over time this residual benefit subsides; however, there are also fewer costs as patients move into better health states and come off treatment. This can be seen in , where, over increased time horizons, the proportion of patients in each health state converges, taking ∼20 years for the two arms to be approximately equal.

Figure 3. Patient distribution over 20-year time horizon, onabotulinumtoxinA and placebo. HA, headache.

In order to model for a ‘full’ horizon, after which the patients in both arms are in the same health states, a 20-year time horizon may be the most appropriate. However, this was not selected as it was felt inappropriate to extrapolate to this horizon based on 24 and 56 weeks of clinical data. Restricting the time horizon to 24 weeks also is inappropriate—at this time point onabotulinumtoxinA- and placebo-treated patients are in vastly different health states (). A 24-week horizon also does not reflect the chronic nature of the condition and treatment.

When the assumptions around the negative stopping rules were varied, the ICER did not change substantially. It increased slightly to £17,190 when no negative stopping rule was applied. The presence of a stopping rule set to 0% (i.e. patients must not worsen) lowers the ICER to £16,456, with results improving if alternative rules are used ().

Removing the positive stopping rule increases the ICER to £16,967. If 100% of episodic patients cease treatment after Year 1 with the positive stopping rule, the ICER decreases to £9141 (). The stopping rules, therefore, can be shown to be important, but not critical, to the cost-effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA.

If no HRQoL benefit with onabotulinumtoxinA is assumed, such that the same utility values are applied to both treatment arms for a health state, the ICER increases to £29,157 (). It should be noted that all HRQoL benefits from onabotulinumtoxinA are due to the improvement in the HRQoL, as no survival advantage is assumed, and this explains why the model is most sensitive to this parameter.

One substantial assumption implicit in the model is that placebo is representative of standard of care. In these studies placebo treatment included multiple injections of saline, which may be the cause of the strong placebo effectCitation33. The decline in headache days seen in placebo-treated subjects may, therefore, over-estimate the efficacy of standard of care, as such a strong effect is unlikely to be seen in clinical practice. If treatment with placebo is assumed to have no impact upon the number of headache days per 28 days (and placebo patients remain in the same health state), the ICER falls to £4945 (). This is likely to be a lower limit, as there could be some unknown amount of regression to the mean, such that patients would improve regardless of being treated or not. A more accurate comparison of no impact of placebo treatment would require data on the natural history of the disease.

When productivity costs are included, such that lost working time is included in calculations, the ICER falls to £9422 (), with the reduction in wage losses offsetting some of the cost of treatment. No other benefits are included (for example carer quality-of-life), therefore with HRQoL remains the same benefit as in the base case.

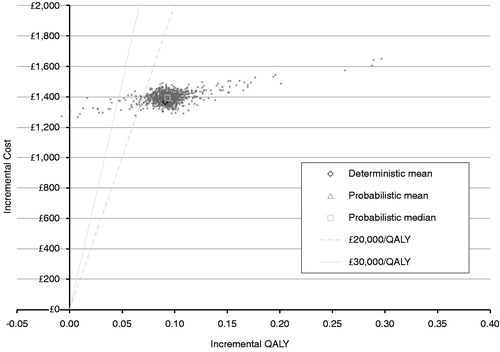

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis was performed and the results plotted on a cost-effectiveness plane with lines representing thresholds of £20,000 and £30,000 (). OnabotulinumtoxinA was cost-effective in 96% of occasions at a willingness-to-pay threshold of £20,000 per QALY and on 98% of occasions at a threshold of £30,000 per QALY.

Discussion

The results of the economic model indicate that onabotulinumtoxinA is cost-effective across a range of populations and stopping rule assumptions. These findings remain consistent with scenario and probabilistic sensitivity analyses given plausible variation in input parameters. Inclusion of workplace productivity costs in the analysis resulted in onabotulinumtoxinA becoming more cost-effective, consistent with studies demonstrating the substantive costs of work-related productivity impacts of migraineCitation34,Citation35.

Our analysis suggests that the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of onabotulinumtoxinA is below the commonly referenced NICE threshold for reimbursement of medical technologies. This is reflected in the NICE single technology appraisal that recently concluded with a positive recommendation for onabotulinumtoxinA in patients who have received three or more prior prophylactic treatmentsCitation19. As the PREEMPT trial was an international multi-centre clinical study, clinical results would also be expected to be generalisable to other countries—the rates of resource utilisation and costs, however, may need adapting in order to be relevant to other countries.

There are, however, limitations to this cost-effectiveness analysis. Placebo as a comparator is not ideal, because saline injections are not a form of treatment used in clinical practice. In this study, saline injections reduced headache days without the side-effects that are common for the preventive treatments used for chronic migraine. It should be noted that these preventive agents are not approved for chronic migraine and are used off-label. Some of these agents have significant side-effects, including cognitive toxicityCitation8. Thus, the tolerability benefits of onabotulinumtoxinA (similar to placebo) are not included. In order to produce an accurate comparison, further data are required on the effectiveness and safety of current practice, of which the majority of treatments have no evidence to support their use.

Second, because onabotulinumtoxinA prophylaxis is not yet widespread in clinical practice, there are limited data available to inform the choice of stopping rules. At the time of publication only one studyCitation25 is available as evidence of a ‘positive stopping rule’. Additionally, although several NHS centres have negative stopping rules in place (for example NHS HullCitation36), best practice has yet to be confirmed. Once onabotulinumtoxinA has been a part of routine clinical practice, preferred clinical algorithms will be developed, allowing for better estimation of the cost-effectiveness of treatment.

Furthermore, the model does not consider patients who discontinue treatment (either because of a stopping rule, or other reasons) who then seek to re-start treatment. There are no data to inform modeling of these patients (and whether they are more, or less, likely to respond), nor is it known how frequently this can be expected to occur in clinical practice. As such they are excluded from this analysis pending data on the effectiveness of onabotulinumtoxinA in this group.

Finally, the PREEMPT trials only provide blinded data for a 24-week period and open-label data for onabotulinumtoxinA a further 32 weeks to Week 56. This model then extrapolated these results to a 2-year time horizon. To allow extrapolation beyond this short time horizon, long-term efficacy data for onabotulinumtoxinA as well as the natural history of disease are needed.

Conclusion

OnabotulinumtoxinA has been shown to reduce headache days in patients with chronic migraine and to improve HRQoL. The comprehensive analyses undertaken demonstrate that onabotulinumtoxinA represents a cost-effective treatment in the UK NHS and offers important benefits to patients poorly served by previous treatments.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Support for this study was provided by Allergan, Inc., Marlow, Buckinghamshire, UK.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

AJB and BWP have disclosed that they are employees of BresMed, a company that received funding from Allergan for its role in developing this manuscript. RNH has no relevant financial relationships to disclose. LMB, SFV, and EJH have disclosed that they are employees of Allergan. LMB has previously owned stock in Allergan, Inc; SFV currently owns Allergan stock, and EJH has none. RBL has disclosed that he receives research support from the NIH [PO1 AG03949 (Program Director), PO1AG027734 (Project Leader), RO1AG025119 (Investigator), RO1AG022374-06A2 (Investigator), RO1AG034119 (Investigator), RO1AG12101 (Investigator), K23AG030857 (Mentor), K23NS05140901A1 (Mentor), and K23NS47256 (Mentor)], the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund; serves on the editorial boards of Neurology and Cephalalgia and as senior advisor to Headache; has reviewed for the NIA and NINDS; holds stock options in eNeura Therapeutics (a company without commercial products); serves as consultant, advisory board member, or has received honoraria from: Allergan, American Headache Society, Autonomic Technologies, Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cognimed, Colucid, Eli Lilly, Endo, eNeura Therapeutics, GlaxoSmithKline, MAP, Merck, Nautilus Neuroscience, Novartis, NuPathe, Pfizer, and Vedanta. SDS has disclosed that he has received research grant support from Allergan, Inc. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Isabelle Girod, Nic Brereton, Patrick Gillard, Rebecca Liu, Lei Liu, Gregory Maglinte, and Juliana Bottomley. The authors wish to acknowledge Imprint Publication Science, New York, NY, USA, for editorial support in the formatting and styling of this manuscript.

References

- Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD. Migraine–current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med 2002;346:257-70

- Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. 2nd edn. Cephalalgia 2004;24(1 Suppl):9-160

- Natoli J, Manack A, Dean B, et al. Global prevalence of chronic migraine: a systematic review. Cephalalgia 2010;30:599-609

- Lipton RB. Tracing transformation: chronic migraine classification, progression, and epidemiology. Neurology 2009;72:S3-S7

- Blumenfeld A, Varon S, Wilcox TK, et al. Disability, HRQoL and resource use among chronic and episodic migraineurs: results from the International Burden of Migraine Study (IBMS). Cephalalgia 2011;31:301-15

- Munakata J, Hazard E, Serrano D, et al. Economic burden of transformed migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache 2009;49:498-508

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Diagnosis and management of headache in adults: a national clinical guideline. Edinburgh, Scotland: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 2008. p 1-81

- NHS Scotland. Neurology – Headache as a new complaint – Adult Patient Assessment Pathway – Migraine [database]. 2010. www.18weeks.scot.nhs.uk. Accessed September 26, 2012

- British Association for the Study of Headache. Guidelines for all healthcare professionals in the diagnosis and management of migraine, tension-type headache, cluster headache, and medication-overuse headache. 2010. http://217.174.249.183/upload/NS_BASH/2010_BASH_Guidelines.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2012

- Bigal ME, Serrano D, Reed M, et al. Chronic migraine in the population: burden, diagnosis, and satisfaction with treatment. Neurology 2008;71:559-66

- Lafata JE, Tunceli O, Cerghet M, et al. The use of migraine preventive medications among patients with and without migraine headaches. Cephalalgia 2010;30:97-104

- Aurora SK, Dodick DW, Turkel CC, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 1 trial. Cephalalgia 2010;30:793-803

- Diener HC, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia 2010;30:804-14

- Dodick DW, Turkel CC, DeGryse R, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache 2010;50:921-36

- Manack AN, Buse DC, Lipton RB. Chronic migraine: epidemiology and disease burden. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2010;15:70-8

- Jhingran P, Osterhaus JT, Miller DW, et al. Development and validation of the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire. Headache 1998;38:295-302

- Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, et al. A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: the HIT-6. Qual Life Res 2003;12:963-74

- Lipton RB, Varon SF, Grosberg B, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA improves quality of life and reduces impact of chronic migraine. Neurology 2011;77:1465-72

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Botulinum toxin type A for the prevention of headaches in adults with chronic migraine. NICE technology appraisal guidance 260. 2012. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13776/59836/59836.pdf. Accessed September 7, 2012

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Migraine (chronic) - botulinum toxin type A for the prophylaxis of headaches in adults with chronic migraine: final scope. 2011. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13554/55946/55946.pdf. Accessed September 9, 2012

- Cady RK, Schreiber CP, Porter JA, et al. A multi-center double-blind pilot comparison of OnabotulinumtoxinA and Topiramate for the prophylactic treatment of chronic migraine. Headache 2011;51:21-32

- Bloudek LM, Hansen RN, Liu L, et al. Health resource utilization and costs for migraineurs in Scotland. Presented at: International Society for Pharmacoecononics and Outcomes Research 16th Annual Conference; May 21–25, 2011; Baltimore, MD. Abstract PND32

- Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology 2007;68:343-9

- Office for National Statistics. Interim Life Tables, England, 1980–82 to 2008–10. UK: Office for National Statistics, 2011

- Rothrock JF, Andress-Rothrock D, Scalon C, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of chronic migraine: long-term outcome. Presented at: American Headache Society (AHS) 53rd Annual Scientific Meeting; June 2–5, 2011; Washington, DC. Abstract P133

- Gillard PJ, Devine B, Varon SF, et al. Mapping from disease-specific measures to health-state utility values in individuals with migraine. Value Health 2012;15:485-94

- British National Formulary. Botulinum toxin type A. 2012. http://www.bnf.org. Accessed September 11, 2012

- Curtis L. Unit costs of health and social care. Canterbury, UK: Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, 2011. http://www.pssru.ac.uk/archive/pdf/uc/uc2011/uc2011.pdf. Accessed September 11, 2012

- National Health Service. NHS reference costs 2009–2010. 2011. London, UK: Department of Health. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_123459. Accessed September 12, 2012

- Health and Social Care Information Centre. Prescription costs analysis for England 2010. http://www.ic.nhs.uk/statistics-and-data-collections/primary-care/prescriptions/prescription-cost-analysis-england–2010. Accessed March 25, 2012

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. 2008. http://www.nice.org.uk/media/B52/A7/TAMethodsGuideUpdatedJune2008.pdf. Accessed August 15, 2012

- Office for National Statistics. Annual survey of hours and earnings. 2010. http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/publications/re-reference-tables.html?edition=tcm%3A77-238620. Accessed March 25, 2012

- Diener HC. Placebo in headache trials. Cephalalgia 2003;23:485-6

- Maglinte GA, Bloudek LM, Stokes ME, et al. Costs associated with lost productive time among working adults with chronic and episodic migraine in the United States and Canada. Presented at: 63rd American Academy of Neurology Annual Meeting; April 9–16, 2011; Honolulu, HI. Abstract P06.015

- Stewart WF, Woods GC, Manack A, et al. Employment and work impact of headache among episodic and chronic migraine sufferers: results of the American migraine prevalence and prevention (AMPP) study. Presented at: 14th Congress of the International Headache Society; September 10–13, 2009; Philadelphia, PA. Abstract PO119

- Allergan, Inc. Allergan comment on Appraisal Consultation Document: Botulinum toxin A for the prevention of headaches in adults with chronic migraine. 2012. UK: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/13554/59149/59149.pdf. Accessed September 9, 2012