Abstract

Background:

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an important, highly disabling neurological disease, common among young adults in The Netherlands. Nevertheless, only a few studies to date have measured the burden imposed by MS on society in The Netherlands.

Objectives:

To estimate the cost and quality-of-life associated with MS in The Netherlands, while focusing on the burden of relapses and increasing disease severity.

Methods:

MS patients in The Netherlands (n = 263) completed a web-based questionnaire which captured information on demographics, disease characteristics and severity (Expanded Disability Status Scale [EDSS]), co-morbidities, relapses, resource consumption, utilities, fatigue and activities of daily living (ADL).

Results:

Most patients included in the study were receiving treatment for MS (76% of the sample). The mean cost per patient per year increased with worsening disability and was estimated at €30,938, €51,056, and €100,469 for patients with mild (EDSS 0–3), moderate (EDSS 4–6.5), and severe (EDSS 7–9) disability, respectively. The excess cost of relapses was estimated at €8195 among relapsing-remitting patients with EDSS score ≤5. The quality-of-life of patients decreased with disease progression and existence of relapses.

Conclusions:

The cost of MS in The Netherlands was higher compared to the results of previous studies. The TRIBUNE study provides an important update on the economic burden of MS in The Netherlands in an era of more widespread use of disease-modifying therapies. It explores the cost of MS linked to relapses and disease severity and examines the impact of MS on additional health outcomes beyond utilities such as ADL and fatigue.

Conclusions:

Study limitations:

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a highly disabling progressive neurological disorder, with the majority of individuals being diagnosed with the disease by the time they reach their 30th year of ageCitation1. MS affects mainly working-age individuals, obstructing their and their families’ personal and professional lifeCitation2.

An assessment that was conducted in 2008 by the Multiple Sclerosis International Federation in collaboration with the World Health Organization and senior MS professionals, revealed that ∼16,000 individuals were affected at that time by the disease in The Netherlands, which was one of the highest estimations among the European countriesCitation3. The disease is observed more frequently among women than menCitation1; in 2008 the point prevalence for women was 1.2 per 1000 vs 0.5 per 1000 for men, as reported by the World Health OrganizationCitation4.

The course of MS is characterized as relapsing-remitting or progressive. Patients with relapsing-remitting MS, the most common type, have periods of symptom remission interrupted by exacerbations, whereas in progressive MS symptoms and disability steadily worsen with or without exacerbationsCitation5.

In the Netherlands MS imposes a significant economic and quality-of-life burden on individuals affected by the disease, their families, the public healthcare system and society as a whole. In 2005, the cost of MS was estimated at €121.4 millionCitation6, whereas a more recent study conducted by the European Brain Council indicated that the total cost of MS in The Netherlands in 2010 was €332 million, with inpatient and outpatient care, informal care provided to MS patients by family and/or friends, and patients’ productivity losses, contributing significantly to the economic burden of the diseaseCitation7. Costs were shown to increase with advancing disability and relapses, since patients’ needs for medical and other types care, or their inability to work, increase due to their aggravating health conditionCitation6.

The quality-of-life burden that is related to MS is linked to the advancing deterioration of the general health of patients due to disease progression and relapses, causing the manifestation of various temporary or permanent problems such as depression, fatigue, impaired cognition, sleep disturbances, bowel and bladder dysfunction, which affect patients’ emotional and physical statusCitation8.

Pharmacological treatments are commonly used in the early stages of MS, aiming to reduce the frequency of relapses and to slow disease progression. Currently, the MS treatments available to patients are interferon beta-1b (Betaferon, Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany), interferon beta 1-a (Avonex, BIOGEN IDEC LIMITED, Zug, Switzerland; Rebif, Merck Serono Darmstadt, Germany), glatiramer acetate (Copaxone, Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., Petach Tikva, Israel), and natalizumab (Tysabri, BIOGEN IDEC LIMITED). A new treatment option for MS patients which was recently approved in EuropeCitation9 and the USCitation10 is fingolimod (Gilenya, Novartis Pharmaceutical Corporation, Basel, Switzerland), an oral treatment that patients take daily. By helping patients with MS to remain relapse-free and to stay at a lower disability level for a longer period of time, disease modifying therapies (DMTs) may reduce the economic and quality-of-life burden associated with the disease.

The objective of the TRIBUNE study that was conducted in The Netherlands was to measure the economic and quality-of-life burden of MS, as well as to contribute in the literature with detailed cost, utility, fatigue, and functional ability information for MS. Furthermore, we focused on examining the relation between disease severity, relapses, and the burden of MS, in particular, the increasing economic and quality-of-life burden caused by advancing disease severity and the existence of relapses.

Materials and methods

The TRIBUNE study is a multi-national, cross-sectional, burden-of-illness survey. The study was first commenced in five European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK) and in Canada during 2009–2010; results for the first six countries are presented elsewhereCitation11–16. During 2011, the study was implemented in two additional countries (Netherlands and Turkey). In this paper, results from The Netherlands are presented.

Study design

Patients were recruited consecutively from seven treatment centers in The Netherlands. Potential participants were identified by the study investigators. Patients were informed about the study and were invited to participate during their scheduled visits to the treatment centers (visits were scheduled for other purposes than the study; no patient visits were related to the study). Only adult (≥18 years old) patients diagnosed with clinically definite MS (ICD-10; G35, ICD-9; 340) were included in the study. MS patients were excluded if they had any physical or mental illness that could lead to their inadequate participation in the study or if they were currently enrolled in a clinical trial. The final study sample only comprised of patients meeting the inclusion criteria who also have provided their consent to participate in the study. No further analysis was conducted including/only with those patients that did not consent to participate in the study.

The study protocol and the questionnaire received approval from the ethics committee prior to study commencement.

Study questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed in Dutch using a web-based electronic data capturing system. Patients were able to access and self-complete the questionnaire through the Internet using their unique credentials (username and password) that were provided to them by the study staff responsible for patient recruitment. It was made explicit to patients that they should complete the questionnaire without any assistance from their family, their physician or others.

Patient characteristics and disease information

Patients were asked to provide information on their age, gender, living arrangements, educational level, employment status, and to indicate their informal caregiver(s) (if any). Disease information including the year patients were diagnosed with clinically definite MS, the year MS symptoms started, the form of MS they were diagnosed with, their disease severity (disability), and any other medical problems they experience (comorbidities) were captured through the questionnaire. For the type of MS, a short description of relapsing-remitting MS, secondary progressive MS, and primary progressive MS were provided for the patient to select from. Disability was captured using the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)Citation17. The version of the scale that was used in this study was patient-rated and ranged from 0–9, with lower scores associated with mild disability/disease severity. This was a modified version that has been previously used in a similar cost-of-illness study in MSCitation18.

Information regarding relapses patients experienced during the past 12 months was also collected through the questionnaire. Patients were asked to report the total number of relapses and how many of those relapses required steroid treatment and/or inpatient care at a hospital (if any), including also the number of days of inpatient care.

Resource utilization

The healthcare as well as the non-medical resources patients used were collected through the questionnaire. Different recall periods were used for different resources. Healthcare resources referring to inpatient care at hospitals or rehabilitation centers or nursing homes, and medical investigations/tests performed, had a recall period of 12 months. Information for other healthcare resources, outpatient care received at hospitals or rehabilitation centers or day visits at nursing homes, consultations with specialists and/or other medical professionals, as well as the use of DMTs, was collected for the past 3 months; patients were also asked to report if they used any prescribed or over-the-counter medication during the past month.

Non-medical resources referring to modifications patients had to make to their home/car or purchasing mobility utensils (e.g. wheelchairs; other walking aids) had a recall period of 12 months. All other non-medical resources that were related to care patients received at home from professionals (nurse, social worker, personal assistant) and from their family and/or friends (informal caregivers) had a recall period of 3 months.

The days off work patients had to take due to sickness were captured through the questionnaire for the past 3 months. Information regarding patients’ retirement due to the impact of the disease on their working ability was also collected.

Costs

To obtain the cost per patient per year, resources were annualized assuming that use during the recall period for each resource was representative of the use over a full year. The annual use of each resource was multiplied by its respective unit cost to get the annual cost.

As with the previous six countries participating in the TRIBUNE study, total costs per patient per year in The Netherlands were calculated from a societal perspective, including all direct healthcare and non-medical costs, as well as patients’ productivity losses.

Unit costs were derived from price lists or published literature for The Netherlands and, where necessary, were inflated to 2011 Euros (€) using the harmonized price indices reported by EurostatCitation18. The per diem inpatient and outpatient costs for hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and nursing homes were retrieved by two publications of studies conducted in The Netherlands; the per diem inpatient costs were extracted from the publication of a previous cost-of-illness study in The Netherlands, conducted by Kobelt et al.Citation19, while the cost for outpatient visits was obtained from the publication by Hakkaart-van Roijen et al.Citation20. Consultation cost was determined per visit and were obtained from the publication by Hakkaart-van Roijen et al.Citation20. The cost per investigation/test procedure was obtained from a third publication by Oostenbrink et al.Citation21.

MS treatments were assumed to be self-injected, apart from natalizumab, for which a visit to the treatment center is needed. However, the cost of the visit was not added to the cost of the medication to avoid double-counting of resources since patients reported separately any MS-related outpatient visits to hospitals/treatment centers they had during the past 3 months. Prices for DMTs were obtained through the price list of pharmaceuticals available in The NetherlandsCitation22; the consumer price was calculated by adding the dispensing and prescription fees to the tariffs reported by the agency, since these prices were only including the VAT. The cost of the other prescribed medication was estimated based on the recommended daily dose, the price across pack sizes, and the dosage strength; the consumer price for each package was based on tariffs from the price list for pharmaceuticals and was estimated using the same method as with the DMTs. The cost for over-the-counter medication was based directly on patients’ reports.

The cost for purchasing walking aids or for performing home or car modifications was obtained from the published costs reported in the study by Kobelt et al.Citation19 in The Netherlands.

The cost of informal care was estimated based on the time patients’ working caregiver spent off work in order to assist them, taking into account the average working hours per week (information not captured through the questionnaire; source OECD, estimation based on the mean working hours per yearCitation23).

The excess cost that could be attributable to relapses was calculated as the difference in the mean annual cost (excluding the cost of MS treatments and investments) between patients with EDSS ≤ 5 who experienced relapse(s) and those who did not. This method is consistent with an earlier burden of illness study in EuropeCitation24. The cut-off value of EDSS ≤ 5 was considered to be the most clinically relevant for the existence of relapses, since it is common that most patients beyond this EDSS level experience disability progression without relapsesCitation25.

Quality-of-life

A health utility index between 0 and 1 with increasing utility representing better quality-of-life was estimated from the EQ-5D scores for each patient. Utility weights, derived from a normal population in the UKCitation26, were used in order to be consistent with the methods and analysis that was performed in the previous six countries participating in the TRIBUNE study. Patients’ scores reported in the visual analogue scale of the EQ-5D instrument were also analyzed.

Fatigue was assessed using the Modified Fatigue Impact Scale (MFIS). MFIS is an MS-specific instrument that consists of 21 questions; the total score is calculated by taking the sum of the scores for the 21 items. Each item has a five-option response (Never = 0, a little of the time = 1, about half the time = 2, a lot of the time = 3, all the time = 4), resulting in a potential total score between 0–84, with higher scores indicating more limitations due to fatigueCitation27.

Ability to perform activities of daily living was assessed using a self-reported version Barthel Index, which consists of 10 items; feeding, moving from wheelchair to bed and return, grooming, transferring to and from a toilet, bathing, walking on level surface, going up and down stairs, dressing, continence of bowels and bladder. Each item is scored based on ability to perform the action; possible scores range from 0, indicating that the person is unable to function, to 3, which equals complete independence in the activity. The total score of this scale is calculated by adding each sub-score of the items, with higher scores indicating a better functionalityCitation28.

Analysis

Patients' demographic and disease characteristics, as well as the resource consumption and the annual costs per patient, were analyzed using descriptive statistics (percentage, mean and standard deviation). In line with the previous six countries participating in the TRIBUNE study, confidence intervals (95%) were estimated by non-parametric bootstrapping, given that costs and quality-of-life outcomes are rarely normally distributed and therefore conventional methods for calculating the confidence intervals were not applicable. For the same reason, a non-parametric statistical test for independent samples (Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test) was used to determine whether differences between comparisons performed were statistically significant (p-value <0.05).

Results

Patient characteristics and disease information

In total, 263 patients in The Netherlands were included in the analysis. Patient demographics and disease information are presented in and . At the time of the study the majority of the patients in the sample were experiencing the relapsing-remitting form of the disease (46%). Disease severity was mild (EDSS 0–3) for 46% and moderate (EDSS 4–6.5) for 43% of patients; only few patients with severe disability (EDSS 7–9) were included in the study (11%). Patients with mild disability were younger than moderate or severe MS patients (p-values <0.0001).

Table 1. Patients' demographic characteristics, by disease severity.

Table 2. Patients' disease characteristics, by disease severity.

Responses regarding employment status indicated that 54% of patients was employed or self-employed or had another form of occupation. A large part of the sample indicated that they were retired due to MS (42%). From those that were on disability pension, 25% had mild disease severity, 53% moderate and 22% were severely disabled.

Co-morbid conditions were more common among patients with moderate disability compared to those with mild disability (); 71% of moderate patients had cognitive impairment, while other common conditions were urinary infections, depression and insomnia. Comorbidities were also linked with the need for informal care since the number of hours per year that patients received assistance from their informal caregivers was higher for patients reporting experiencing at least one co-morbid condition compared to those with no other disorders in addition to MS (348 vs 158 h, p-value = 0.006).

Among the 114 patients with the relapsing-remitting form of the disease and a disability level up to EDSS 5, 59 (52%) reported experiencing at least one relapse during the past 12 months. The number of relapses experienced by these individuals ranged between 1–4. No statistically significant differences in the patient demographics and the disease severity and other characteristics were observed when comparing the two sub-groups (relapsing-remitting patients with EDSS ≤ 5 with and without relapses; p-values >0.05 for all comparisons).

Resource utilization

At study commencement, the majority of patients (76%) were receiving treatment for MS; 35% were patients with mild MS disability, compared to 33% with moderate and 8% with severe MS disability. Inpatient stays in hospitals, rehabilitation centers or nursing homes were reported only by few patients; 7% of mild patients, 13% of moderate, and 28% of severe patients. As with inpatient care, an increase in the use of other healthcare resources was observed with advancing disability; outpatient visits were more frequent among moderate than mild patients (47% vs 34%), consultations with specialists and other healthcare professionals were reported by ∼84% mild and moderate patients but were more frequent among severe patients (93%). The use of prescribed (other than MS treatments) and over-the-counter medication was also associated with advancing disability; 73% of mild patients vs 89% of moderate, and 97% of severe patients reported receiving other medication.

Non-medical resources were higher among patients with more severe MS. The mean number of hours per patient per year for professional care was 22 in the mild MS group, but 102 in the moderate MS group and 523 in the severe MS group (p-values <0.05 for all comparisons). Informal care followed the same pattern with mild patients reporting 80 h of care vs 270 h reported by moderate patients and 730 h for severe patients (p-values <0.05 for all comparisons).

Mild MS patients reported a higher number of sick-leave hours per year (174 h) compared to moderate patients (34 h). This relates to the fact that with disease progression patients retire from work and, therefore, there is a reduction in the sick leave patients require.

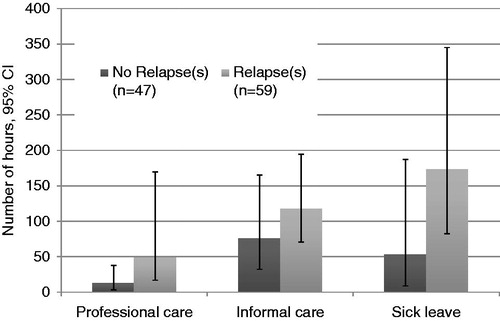

Patients with the relapsing–remitting form of MS who had an EDSS score ≤5 and experienced relapse(s) during the past 12 months reported a higher consumption of healthcare resources compared to the same sub-group of patients not experiencing any relapses. Consumption of non-medical resources and sick-leave days was also higher for patients with relapses compared to those without ().

Costs

The total cost per patient per year estimated at €47,173, 26% of which were attributable to direct medical costs. Direct non-medical costs accounted for 31% of total costs, while indirect costs represented almost half of total costs (43%).

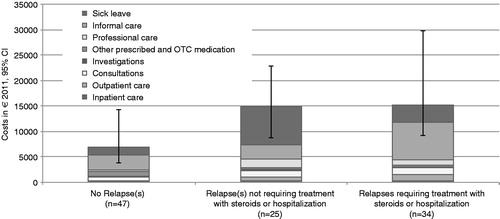

As shown in , total costs varied among severity sub-groups, with the lowest cost being for patients with mild disability. Across the severity sub-groups, the relative contribution of the various cost components differed; for example, direct healthcare costs comprised a larger proportion of total costs in mild compared to moderate disability sub-groups. Non-medical costs (investments, professional, and informal care) and indirect costs (sick-leave and early retirement due to disability) contributed less to total costs in the sub-group of moderate patients compared to the one with severe patients.

Table 3. Direct medical, non-medical, indirect, and total costs per multiple sclerosis patient per year (Euros 2011), by disease severity.

Relapses contributed to excess costs. The additional cost was estimated by the difference in the costs among patients with the relapsing–remitting form of the disease and an EDSS score of 5 or lower that did experience at least one relapse during the past 12 months (€15,094) compared to those that did not (€6899) (p-value = 0.001); the excess cost was estimated at €8195. The cost per patient per year was higher for patients requiring steroid treatment for relapses, with or without hospitalization (€15,248), compared to the cost for patients receiving no steroid treatment or hospitalization (€14,885) (p-value = 0.645) ().

Quality-of-life

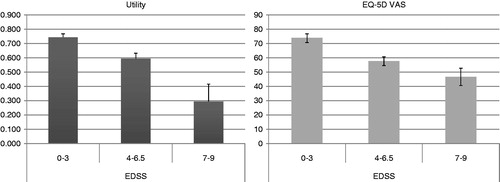

Disease severity was also associated with the quality-of-life reported by patients. As shown in , it was estimated that patients with higher disability had lower utilities and EQ-5D scores on the visual analog scale (p-values <0.05 for all comparisons).

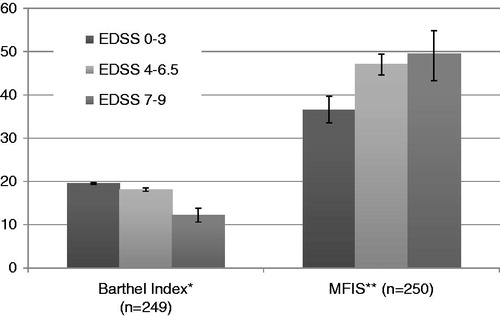

Fatigue and limitations in performing everyday activities were more prominent in patients with higher disability compared to patients experiencing mild disease severity (p-values <0.0001 for all comparisons with the exception of the fatigue score between moderate and severe patients; p-value = 0.353) ().

Figure 4. Fatigue and ADL (95% CI), by disease severity. *The Barthel Index score is decreasing with increasing disability. **The MFIS score is increasing with increasing disability.

Relapses and relapse severity were also associated with worsening quality-of-life. Fatigue scores were higher for relapsing–remitting patients with EDSS ≤ 5 that reported having a relapse (42 vs 34 on the MFIS scale, p-value <0.05). When looking into the severity of relapses, fatigue scores increased from 41 for patients with relapse(s) but requiring no treatment with steroids of hospitalization, to 43 for patients with relapse(s) that received steroid treatment and/or hospitalization (p-value >0.05).

The differences in patients’ ability to perform activities of daily living was not strongly associated with relapses, since the scores of Barthel Index did not change significantly (p-value >0.05) with the existence of relapses (19.51 for patients without relapses and 19.52 for patients with at least one relapse during the past 12 months). Relapse severity was not a relevant factor for the Barthel Index scores.

Utilities for relapsing–remitting patients with EDSS ≤ 5 that did experience a relapse was similar to those not experiencing any relapses. The EQ-5D score from the visual analog scale for patients with relapse(s) was lower compared to those without (74 vs 69; p-value = 0.066).

Discussion

The main objective of the TRIBUNE study was to measure the cost of Multiple Sclerosis in The Netherlands and examine its association with disease severity and relapses. In total, 263 patients were included in the study. A large proportion of the MS patients in the sample were experiencing the relapsing–remitting form of the disease (46% of the total sample) and were receiving treatment with disease modifying therapies (76% of the total sample) at the time of the study. In addition, a large part of the sample reported being retired from their work due to MS (42% of the total sample).

The TRIBUNE study estimated the mean cost per patient with MS at €47,173. Direct and indirect costs increased with disease severity, which can be explained by a higher need for medical and non-medical care associated with progressing disability and limitations in everyday living. In fact, the mean cost per patient was estimated at €30,938 among those with mild disease severity (EDSS 0-3), while it increased to €38,812 and €63,821 for patients with moderate (EDSS 4–6.5) and severe (EDSS 7–9) disability. Our findings suggest that, as disease progresses, cost components like professional or informal care, as well as productivity losses, play an increasingly important role in the total economic burden of the disease.

The excess cost that could be associated with MS relapses was estimated at €8195 over 12 months. The cost components that contributed the most to the excess burden were inpatient and outpatient care, informal and professional care, as well as sick leave. For relapses of short duration, this could be considered an over-estimation since the difference in costs may be attributed to factors other than the relapse itself, such as differences in disease progression. However, one could also argue that, since the study design did not allow capturing the full period of increased costs for patients who experienced two, three, or more relapses, this average cost is an under-estimation of the excess economic burden due to relapses.

The severity of MS relapses was also a factor that was associated with the excess cost. We showed that the excess cost of relapses was higher when patients had more complications during relapses and they required treatment with steroids and/or inpatient care, compared to those not in such a need (costs: €14,885 for relapses not requiring treatment with steroids or hospitalization vs €15,248 for severe relapses that led to steroid treatment and/or hospitalization). The difference in costs was not found to be statistically significant; however, the interpretation of the statistical hypothesis testing and significance levels is not the same within the context of cost-of-illness studies as in a clinical trial framework. Rather than testing a hypothesis, the objective of a cost-of-illness study is to estimate the economic burden, providing point estimates that are of relevance for decision-makers, irrespective of statistical significance.

In addition to the association of costs with MS severity and relapses, we estimated that there is a decrease in the quality-of-life of MS patients as disease progresses. Utility scores, fatigue, and the difficulties patients with MS face when performing activities of daily living were linked with disease severity (advancing disability implying more limitations). An association between patients’ quality-of-life and the existence of relapses was also found; the results of the EQ-5D visual analog scale and the fatigue scale were worse for the relapsing–remitting patients with EDSS score ≤5 that did experience at least one relapse during the past 12 months when compared to the same sub-group of patients without any relapses.

When comparing our with previous studiesCitation29, we found that the proportion of RRMS patients in TRIBUNE was higher compared to 24% of MS patients diagnosed with RRMS in 1992 at the province of Groningen, The Netherlands. In addition, a previous cost-of-illness study conducted in The Netherlands in 2005Citation1Citation9 included 30% of patients with the relapsing–remitting form of the disease. In the same study, only 36% of the total sample was receiving disease-modifying therapies at the time of the study. These differences were expected given that the intention of TRIBUNE was to have a patient sample that is as representative as possible of the MS population for which treatment decisions are made (hence the high proportion of patients that were diagnosed with RRMS and were receiving disease-modifying therapies).

In terms of the high proportion of patients that were retired due to MS, it was found to be in accordance with previous research; in fact, the previous cost-of-illness study for MS in The Netherlands had also 42% of the sample that was retired from their work due to the diseaseCitation19. The number of patients retired from work in the TRIBUNE study in The Netherlands was the highest among all other European countries that participated in the study (42% in The Netherlands vs 4–27% in the other European countriesCitation9–14). We could speculate that this finding is due to the differences in the social and welfare benefits available across countries.

The TRIBUNE cost findings are consistent with conclusions from previous cost-of-illness studies of MS in The Netherlands. The most recent cost-of illness study, by Kobelt et al.Citation19, estimated that the mean cost per patient per year was €32,408 (2011 Euro prices; conversion from 2005 Euro prices) and increased with advancing disease severity. Differences in costs are likely to be explained by differences in the study design and analysis assumptions between the two studies related to, e.g., the recall period for reporting the consumption of various resources, how the productivity losses of the informal caregiver are valued, and methods used to impute missing observations. In addition, any differences between the two studies in the average disease severity of the sample or any extreme cost observations for some individuals (outliers) are likely to drive the variation in costs.

The number of patients treated and the availability of disease modifying therapies at the time of the study is also a factor that contributes to the differences in the observed mean costs. In the TRIBUNE study, the cost of MS treatments was considerably higher compared to the previous cost-of-illness study for MS in The NetherlandsCitation19; €4638 (2011 Euro prices; conversion from 2005 Euro prices) compared to €8727 from our study. This difference could be attributed to the higher number of MS patients included in the TRIBUNE study that were receiving treatment with DMTs (76% vs 36% in the Kobelt et al.Citation19 study). Also, the fact that natalizumab was not an available MS treatment when the study by Kobelt et al.Citation19 was conducted is a factor that could probably explain the higher treatment costs observed in the TRIBUNE study; 23% of patients in TRIBUNE that were treated at the time of the study were receiving natalizumab, and since the cost of this disease modifying therapy is higher compared to interferons and copaxone, the cost for MS treatments is higher compared to the study by Kobelt et al. when natalizumab was not available. Numeric differences in other costs items such as professional and informal care, and patients’ productivity losses could also be attributed to the fact that the TRIBUNE sample had a higher number of patients that reported having at least one relapse during the past 12 months (50% compared to 30% in the study by Kobelt et al.Citation19). Our findings suggest that MS relapses are associated with the excess consumption of resources and excess productivity losses, which leads to a higher economic burden.

Cost results from the other European countries (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK)Citation11,Citation13–16 and CanadaCitation12 that participated in TRIBUNE are also in line with the Dutch results. In all TRIBUNE countries, the economic burden increased with disease severity. The cost of MS treatments was the main contributor to the direct healthcare costs. When looking into the direct non-medical costs, the economic burden related to the help MS patients received from their informal caregivers was contributing the most to this cost category, with the exception of severe MS patients in France where the cost for investments and modifications was higher. Indirect costs, and in particular the burden associated with MS patients retiring early due to an inability in performing their profession, was higher in The Netherlands compared with the other countries participating in TRIBUNE, which, as mentioned above, is due to the higher number of patients that were retired from their profession early due to their disability in The Netherlands.

Despite the similarities, there are numeric differences in the estimated total costs among the countries participating in TRIBUNE. The total costs in The Netherlands are higher in comparison to the other countries participating in the TRIBUNE study. This fact could partly be explained by the contribution of early retirement in the total costs, but it could also be attributed to the difference in the costs for a unit of healthcare and other social care services, as well as to the higher underlying severity of the study sample in The Netherlands compared to the other TRIBUNE countriesCitation12,Citation30. This last case should be mentioned with the exception of the UK, where the mean disease severity in the study is similar to the Dutch TRIBUNE sample, yet the mean total cost is higher in The Netherlands. This could be explained by the variation of the distribution of mild, moderate, and severe patients within the two study populations; for instance, if we look into the study population for the UKCitation16, there are more patients with very mild disease severity (EDSS 0–1) compared to the respective sample in The Netherlands (20% vs 17% of all patients), suggesting that the mean total cost in the UK is lower when compared to the Dutch findings since there are more very mild patients contributing a low economic burden to the mean total costs.

We followed some of the main assumptions of the previous most recent cost-of-illness study in The Netherlands in order to estimate the excess cost attributable to relapses in MS. The Kobelt et al.Citation19 study indicated that all patients with EDSS < 5 that did experience relapse(s) had higher costs compared to those without a relapse; the difference was €3086 (Euro 2011 prices; conversion from 2005 Euro prices) over a 3-month period. The results of our study showed that the difference in costs among patients with the relapsing–remitting form of the disease with EDSS ≤ 5 that did or did not experience relapse(s) was €8195 over 12 months. The difference in the results when comparing the studies is likely to be explained by the different cost components that were used in order to measure the economic burden attributable to relapse(s); while the study by Kobelt et al.Citation19 included all cost items in the calculation of the difference in economic burden due to the presence of relapse(s), our study focused on the direct healthcare, non-medical, and indirect costs excluding costs of MS treatments, costs due to modifications, and costs of retirement due to the disease. The decision for excluding these items was based on the assumption that relapses are unlikely to have an impact on intake of DMTs, home/car or other modifications, and retirement due to MS; these items are mainly expected to be correlated with disease severity.

The TRIBUNE findings regarding the excess burden of relapses in The Netherlands are in accordance with the results we observed in the other European countries and CanadaCitation11–16. The variation in the excess economic burden that could be attributed to relapses could most likely be explained by the difference in the underlying severity of the study populations used in the analysis for relapses (RRMS patients with EDSS score ≤5). It should also be noted that, while in the other countries that participated in the TRIBUNE study the sub-group of relapsing–remitting patients with EDSS ≤ 5 and with at least one relapse had a statistically significant higher disability (p-value <0.05) in comparison to the same sub-group of patients without relapses, in The Netherlands the two sub-groups were very similar in terms of the underlying disease severity (p-value >0.05); therefore, in The Netherlands there was no need to correct for the difference in disability in the sub-groups when estimating the excess burden associated with relapses, as it was done for the other European countries and Canada that participated in TRIBUNE.

Regarding the quality-of-life results of the TRIBUNE study, and how they are associated with disease progression, they are in line with the findings of the previous cost-of-illness study in The NetherlandsCitation19 and with the results of the other countries that participated in TRIBUNECitation12,Citation30. Quality-of-life was found to decrease with relapses, and this result is in line with the outcomes of the pooled quality-of-life analysis across the other European countries participating in the TRIBUNE studyCitation30. However, for The Netherlands, limitations in activities of daily living and utilities were not strongly associated with relapses since there was not a considerable change in the scores when comparing the two sub-groups of MS patients used for the analysis for the impact of MS relapses. This finding was not as expected, given that in all other countries that participated in the TRIBUNE study, relapses were associated with a statistically significant excess burden in terms of loss of utilities and additional limitations due to disability, inhibiting individuals’ performance in daily activities. A possible reason could be the fact that the sample size used for the analysis of the association between the quality-of-life results and relapses was considerably higher for the other European countries (pooled analysis across the first five European countries) when compared to the sample size for The Netherlands; therefore, this could explain the fact that we do not observe as high differences in The Netherlands as we do for the other European countries.

The TRIBUNE study contributes in the literature for The Netherlands with an important update regarding the burden associated with the disease in terms of costs and quality-of-life, in an era of more widespread use of MS therapies. Our study included MS patients that were receiving traditional and novel therapies (Tysabri); to our knowledge, this is the first burden-of-illness study that includes patients treated with Tysabri. The entire disease disability spectrum was covered in the patient sample, and thus the comparability of results with a general MS population is reinforced. However, only a few patients with severe disability were included in our study, therefore a larger sample is needed in order to generalize the results according to disease severity.

Another limitation relates to the fact that the cost estimates are likely to reflect how the sample of MS patients was derived. Total cost estimates would probably have been lower if the sample had included MS patients recruited from community neurology practices rather than only specialized clinics, due to the fact that patients coming from community practices are likely to have less severe disease and are treated with DMTs less frequently. Indeed, the proportion of patients in our sample who reported receiving treatment with DMTs or having a relapse was relatively high. In addition, if patients from nursing homes/chronic care institutions had been included in the sample, the costs attributed to the use of DMTs would have been lower, but other direct healthcare costs would have been higher in comparison with patients living in the community.

In conclusion, the TRIBUNE study reports important information on costs and quality-of-life of MS patients in The Netherlands. Considering that total costs of MS increase and quality-of-life decreases with advancing disease severity and with relapses, slowing progression and reducing the frequency of relapses presents an opportunity to reduce the burden of MS. Further research is needed in order to explore the precise relationship between disease rate and relapse rate reduction and long-term benefits of MS treatments, whether or not the treatment paradigm currently available in The Netherlands is optimal, as well as the impact of MS patient programs on costs and the quality-of-life of MS patients.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The TRIBUNE study was supported by Novartis Pharmaceuticals.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

Korinna Karampampa, Anders Gustavsson, and Carolin Miltenburger have disclosed that they are former employees of OptumInsight, the consultancy company that implemented the TRIBUNE study with the financial support from Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Martijn Groot, Milon Relleke, and Saskia van der Hel have disclosed that they are employees of Novartis Pharmaceuticals, The Netherlands. Evert A. C. M. Sanders, Erik Th. L. van Munster and Raymond M. M. Hupperts have no relevant financial relationships to disclose. Jaap de Graaf has disclosed that he is a consultant to Novartis and Biogen Idec. Paul Pop has disclosed that he is a consultant to Novartis. Okke L. G. F. Sinnige has disclosed that he is a consultant to Biogen Idec, Genzyme, Merck Serono, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. He has also received grants from Biogen Idec, Merck Serono, and Teva. TRIBUNE was designed from OptumIsight, in collaboration with Novartis Pharmaceuticals. MS patients participating in the study were identified by the study investigators alone (no involvement of Novartis Pharmaceuticals or OptumInsight). Data collection was performed electronically; patients completed the questionnaire without any help from the study investigators or others. All authors were involved in the data analysis and/or interpretation of the results presented in this manuscript, and in writing and/or providing critical revisions to the manuscript. All authors provided their consent to publish this manuscript. JME Peer Reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the study investigators and their collaborators who participated in the TRIBUNE study in The Netherlands.

References

- Pugliatti M, Rosati G, Carton H, et al. The epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Europe. Eur J Neurol Official J Eur Fed Neurol Soc 2006;13:700-22

- Koutsouraki E, Costa V, Baloyannis S. Epidemiology of multiple sclerosis in Europe: a review. Int Rev Psychiatry 2010;22:2-13

- Multiple Sclerosis International Federation. Atlas of MS Database. Total Number of people with MS in the Netherlands, 2008 data. http://www.atlasofms.org. Accesed November 2012

- Lalmohamed A, Bazelier MT, Van Staa TP, et al. Causes of death in patients with multiple sclerosis and matched referent subjects: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Neurol 2012

- Duddy M, Haghikia A, Cocco E, et al. Managing MS in a changing treatment landscape. J Neurol 2011;258:28-39

- Kobelt G, Kasteng F. Access to Innovative treatments in multiple sclerosis in Europe. 2009. Comparator reports. http://www.comparatorreports.se/Access%20to%20MS%20treatments%20-%20October%202009.pdf. Accessed November 2012

- Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jacobi F, et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2011;21:718-79

- Marrie RA, Horwitz R, Cutter G, et al. Comorbidity, socioeconomic status and multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2008;14:1091-8

- European Medicines Agency. 2011. http://www.ema.europa.eu. Accessed September 2011

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2011. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/NewsroomPressAnnouncements/ucm226755.htm. Accessed September 2011

- Johansson E, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from France. Mult Scler 2012;18:17-22

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden, and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in multiple sclerosis: the costs and utilities of MS patients in Canada. J Popul Ther Clin Pharmacol 2012;19:e11-25

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from Spain. Mult Scler 2012;18:35-9

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from Germany. Mult Scler 2012;18:23-7

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from Italy. Mult Scler 2012;18:29-34

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from the United Kingdom. Mult Scler 2012;18:41-5

- Kurtzke JF. A new scale for evaluating disability in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 1955;5:580-3

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, et al. Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis in Europe: method of assessment and analysis. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7(Suppl 2):S5-13

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, et al. Costs and quality of life in multiple sclerosis in The Netherlands. Eur J Health Econ 2006;7(Suppl 2):S55-64

- Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Tan SS, Bouwmans CAM. Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek, methoden en standaard kostprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. Geactualiseerde versie 2010. Instituut voor Medical Technology Assessment, Erasmus MC in opdracht van College voor zorgverzekeringen. ErasmusUniversiteit Rotterdam. The Netherlands. http://www.cvz.nl/binaries/live/cvzinternet/hst_content/nl/documenten/losse-publicaties/handleiding-kostenonderzoek-2010.pdf. Accessed November 2012

- Oostenbrink JB, Bouwmans CAM, Koopmanschap MA, et al. Handleiding voor kostenonderzoek: methoden en standaard kostprijzen voor economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. Geactualiseerde versie 2004. [Handbook for cost studies: methods and standard costs for economic evaluation in health care. Updated version 2004]. Instituut voor Medical Technology Assessment, Erasmus MC in opdracht van College voor zorgverzekeringen. ErasmusUniversiteit Rotterdam. The Netherlands. http://www.ispor.org/peguidelines/source/Methodenenstandaardkostprijzenvooreconomischeevaluatiesindegezondheidszorg.pdf. Accessed November 2012

- Medicijnkosten. 2012. http://www.medicijnkosten.nl/. Accessed November 2012

- OECD -- Average annual hours worked. 2011. http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=ANHRS. Accessed November 2012

- Kobelt G, Berg J, Lindgren P, et al. Costs and quality of life of patients with multiple sclerosis in Europe. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2006;77:918-26

- Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet 2008;372:1502-17

- Dolan P, Gudex C, Kind P, et al. A social tariff for EuroQol: results from a UK General Population Survey. York: Centre for Health Economics, Universityof York, 1995

- Meads DM, Doward LC, McKenna SP, et al. The development and validation of the Unidimensional Fatigue Impact Scale (U-FIS). Mult Scler 2009;15:1228-38

- Marrie RA, Goldman M. Validity of performance scales for disability assessment in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2007;13:1176-82

- Minderhoud JM. On the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. A revised model of the cause(s) of multiple sclerosis, especially based on epidemiological data. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 1994;96:135-42

- Karampampa K, Gustavsson A, Miltenburger C, et al. Treatment experience, burden and unmet needs (TRIBUNE) in MS study: results from five European countries. Multe Scler 2012;18:7-15