Abstract

Objective:

This study examined the proportion and magnitude of dose escalation nationally and regionally among rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients treated with TNF-blockers and estimated the costs of TNF-blocker therapy.

Methods:

This retrospective cohort study used claims data from US commercially-insured adult RA patients who initiated adalimumab, etanercept, or infliximab therapy between 2005–2009. Biologic-naïve patients enrolled in the health plan for ≥6 months before and ≥12 months after therapy initiation were followed for 12 months. Dose escalation was assessed using three methods: (1) average weekly dose > recommended label dose, (2) average ending dispensed dose > maintenance dose, and (3) average dose after maintenance dose > maintenance dose. Annual cost of therapy included costs for mean dose and drug administration fees.

Results:

Overall, 1420 etanercept, 874 adalimumab, and 454 infliximab patients were included. A significantly lower proportion of etanercept-treated patients had dose escalation using the average weekly dose (3.9% vs 21.4% adalimumab and 69.6% infliximab; p < 0.0001), average ending dispensed dose (1.1% vs 10.6% adalimumab and 63.0% infliximab; p < 0.0001), and average dose after maintenance dose methods (2.8% vs 15.7% adalimumab and 69.6% infliximab; p < 0.0001). Regional dose escalation rates and magnitudes of escalation were directionally consistent with national rates. Etanercept had the lowest cost per treated RA patient ($19,690) compared to adalimumab ($23,020) and infliximab ($24,030).

Limitations:

Exclusion of patients not on continuous TNF-blocker therapy limits the generalizability; however, ∼50% of patients were persistent on therapy for 12 months. The study population comprised RA patients in commercial health plans, thus the results may not be generalizable to Medicare or uninsured populations.

Conclusions:

In this retrospective study, etanercept patients had the lowest proportions and magnitudes of dose escalation across all methods compared to adalimumab and infliximab patients nationally and regionally. Mean annual cost was lowest for etanercept-treated patients.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic, inflammatory diseaseCitation1,Citation2 that leads to significant clinical, functional, and psychosocial burdens for patientsCitation3–6 and substantial economic burdenCitation7–9. A recent US study estimated the total annual cost of RA as $19.3 billion, with $8.4 billion in direct healthcare costs and $10.9 billion in indirect costsCitation8. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) blocker therapy has been shown to be effective in the treatment of moderate and severe RA. Randomized clinical trials and open-label extensions have demonstrated significant improvements in the signs and symptoms of RA and inhibition of progressive joint destruction with etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximabCitation10–13.

Etanercept is a recombinant human soluble TNF-receptor protein, and adalimumab and infliximab are anti-TNF monoclonal antibodies. Adalimumab is approved for treatment of RA at 40 mg every other week with the ability to increase the dose up to 40 mg every weekCitation14. Infliximab is FDA-approved for weight-based dosing of 3 mg/kg every 8 weeks, with the ability to increase the dose up to 10 mg/kg every 8 weeks or increase the frequency of infusions to every 4 weeksCitation15. The US prescribing information for etanercept allows for a fixed dose of 50 mg weekly in RACitation16.

Dose escalation is associated with higher drug treatment costs and greater risk for adverse events. Evaluations of US managed care data have shown that patients with dose increases or high starting doses had significantly higher costs compared with patients without high starting doses or dose escalationCitation17,Citation18. In addition to the added costs, increasing the dose of a TNF-blocker beyond the minimum recommended label dose increases the risk of side-effects such as infections and injection site reactionsCitation19–21.

In observational RA studies of TNF-blocker dosing patterns, etanercept dose escalations were significantly lower and the cost of etanercept therapy was lowerCitation17,Citation18,Citation22–27. However, these studies examined drug utilization patterns before 2006 and did not always account for the impact of therapy persistence or computed dose escalation based on the initial dose. Also, managed care plans implemented various cost management efforts (e.g., step therapy, therapeutic interchange, prior authorization) for use of TNF-blockers in recent years which may impact utilization patternsCitation28. The present study estimated the dose escalation patterns and TNF-blocker costs nationally and regionally for biologic naïve RA patients initiating etanercept, adalimumab, or infliximab therapy between 2005–2009 and continuing therapy for 12 months (up to June 2010).

Methods

A retrospective cohort study was conducted with commercially-insured adult RA patients using administrative claims data from the IMS LifeLink Health Plan Claims database. The LifeLink database is comprised of fully adjudicated medical (inpatient and outpatient diagnoses and procedures) and pharmacy (retail and mail order prescriptions) claims for over 70 million patients from over 100 health plans (∼20 million lives per year) across the US. The LifeLink population is representative of the US commercially-insured population in terms of age, gender, and type of health plan. In compliance with the Health Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), patient data included in the analysis was de-identified. As a retrospective analysis of de-identified data, the study was exempt from Institutional Review Board review under 45 CFR 46.101(b)(2).

Study population

Patients were included in the study if they met the following criteria: (1) initiation of etanercept, adalimumab, or infliximab between July 1, 2005 (after FDA approval for adalimumab) and June 30, 2009, (2) continuous enrollment in the health plan for 6 months before through 12 months after therapy initiation, (3) 18–64 years of age at time of therapy initiation, (4) at least one inpatient or two outpatient medical claims with a diagnosis of RA (ICD-9 code of 714.0x) in the 6 months before therapy initiation, (5) persistent on TNF-blocker therapy for 12 months after initiation to ensure an opportunity for dose escalation, and (6) initiated therapy at a minimum of the recommended label dose (i.e., at least 50 mg/week for etanercept, 20 mg/week for adalimumab, and 5 mg/kg for infliximab). Initiation of therapy was determined as the absence of biologic therapy in the 6 months prior to therapy initiation within the study period. The date of the first TNF-blocker claim within the study period was defined as the index date.

Patients were excluded from the study if they had the following diagnoses during the pre- or post-index periods: psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, lupus, multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, cancer, or HIV. Patients were also excluded if they used any of the following agents during the 6 months prior to index date or switched to any other agents (anakinra, abatacept, adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab, infliximab, rituximab, or tocilizumab) during the 12-month post-index period.

Patients were followed from therapy initiation (index date) through the first 12 months of therapy. The TNF-blocker received on the index date was used to classify patients into medication cohorts (etanercept, adalimumab, or infliximab).

Study measures

To assess dose increases, a consistent starting point for each TNF-blocker needed to be established against which subsequent doses could be evaluated. In this study, the maintenance dose, or first stable dose, was identified as the starting point. The maintenance TNF-blocker dose was defined as the dose of the first prescription for etanercept and adalimumab. The maintenance dose for infliximab was the fourth infusion because of the titration period during the first 6 weeks (weeks 0, 2, and 6). Since infliximab dose is weight-based, the average weight for 20–74 year old males (86.8 kg) and females (74.7 kg) for the US population based on the National Health and Nutrition Examination SurveyCitation29 was used to estimate recommended label dose. Therapy persistence was defined as continuous use of the index medication during the first 12 months of follow-up without any gaps in therapy >60 days. Gaps in therapy were identified as the time between the run-out of a prescription fill (fill date + days supply) until the fill date of the next fill. For infliximab, days supplied was imputed to be 56 days (i.e., 8 weeks), so a gap was defined as 60 days + 56 days or greater.

The proportion of patients with dose escalation was calculated using three methods which differed on the comparators used in the computation:

Average weekly dose: Dose increase was defined as having an average weekly dose (total dispensed quantities in the study period/total days supply) > the recommended label dose.

Average ending dispensed dose (first stable dose vs last dose): Dose increase was defined as the average ending dispensed dose that is greater than the maintenance dose; [(average ending dispensed dose – average starting dispensed dose)/average starting dispensed dose] × 100, and >0 to be classified as dose escalation. For etanercept and adalimumab, the weekly dose from the index prescription was used as the average starting dispensed dose. For infliximab, the weekly dose from the first stable prescription (fourth infusion) was used as the average starting dispensed dose.

Average dose after maintenance dose: Dose increase was defined as an average dose after the maintenance dose that is greater than the maintenance dose; [average dose after maintenance dose – maintenance dose)/maintenance dose] × 100, and >0 to be classified as dose escalation. For adalimumab and etanercept, the weekly dose from the index prescription was used as the maintenance dose and the weekly dose from all other prescriptions within the 12-month period was used as the average dose after maintenance dose. For infliximab, the weekly dose from the first stable prescription (fourth infusion) was used as the maintenance dose, and the weekly dose from all other prescriptions within the 12-month period after the fourth infusion was used as the average dose after maintenance dose.

Magnitude of dose escalation was calculated for the average ending dispensed dose method and dose after maintenance dose method for each patient; then the mean was computed for each treatment cohort. The percentage increase in dose from starting dose to ending dose (for the average ending dispensed dose method), and from maintenance dose to average dose after maintenance dose (for the average dose after maintenance dose method) was calculated. For the average weekly dose method, magnitude of dose escalation was not calculated. Instead the proportion of patients whose average dose exceeded the recommended dose by 130% was calculated to ensure that small variations in dose over time were not included in the magnitude of dose escalation.

Total TNF-blocker costs were calculated for each patient by multiplying the total annual mean dose with the 2011 September wholesale acquisition cost (WAC; $452.44 for 50 mg of etanercept, $896.35 for 40 mg of adalimumab, and $710.12 for 100 mg of infliximab). A standard cost metric (WAC) was applied to the annual mean dose to standardize costs over timeCitation30. Based on the distribution from claims data, intravenous administration costs for infliximab were assumed to be 2 hours per infusion. Using the June 2011 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule, infusion fees for the initial hour ($146.44) and 1 subsequent hour ($31.26) were applied to each infliximab infusion and added to the total infliximab drug costs. It was assumed that a provider administered the first subcutaneous injection ($23.10) and then patients self-administered subcutaneous treatment (no cost) for the remaining duration of therapy. The total annual dose was calculated as the sum of all doses received for each TNF-blocker during the 12 months following initiation of therapy.

Statistical analysis

The dose escalation results were stratified by treatment group (etanercept, adalimumab, or infliximab) and descriptive statistics computed. Statistical tests of significance for differences in the distributions were conducted by treatment group. Chi-square tests were used to evaluate the differences in categorical variables; t-tests were used for normally distributed continuous variables, and non-parametric Wilcoxon tests were used for continuous variables that were not normally distributed. A statistical significance level of p < 0.05 was used.

Results

There were 2748 RA patients who met the study criteria; 1420 (51.7%) etanercept, 874 (31.8%) adalimumab patients, and 454 (16.5%) infliximab. Few patients were excluded due to lack of persistence on TNF blocker therapy (2.8% of patients) or below recommended dose (0.13%). Patient characteristics across the TNF-blocker cohorts were similar except for age, geographic region, and NSAID and analgesics use prior to TNF-blocker therapy initiation (). Etanercept patients were younger (49.9 years) than infliximab patients (51.2 years; p = 0.02). Fewer adalimumab patients lived in the Northeast and West US compared with etanercept patients (p < 0.001), and more etanercept patients lived in the Midwest and West US than infliximab patients (p = 0.0005). A greater proportion of etanercept patients received NSAIDs (81%) and analgesics (82%) in the 6 months prior to initiating TNF-blocker therapy compared with infliximab patients (74% NSAIDs and 74% analgesics; p < 0.01 for both). Glucocorticoids were received prior to TNF-blocker therapy initiation for 91–93% of patients. Between 24% (infliximab) and 39% (etanercept) of patients received hydroxychloroquine and 14–16% received sulfasalazine prior to initiating TNF-blocker therapy. Similar patient characteristics were observed across the four US geographic regions, except the age difference occurred only in the South, and no difference in pre-index concomitant medication use across the TNF-blockers was observed for the Midwest and South.

Table 1. Characteristics (nationally and regionally) among patients with RA who initiated TNF-blocker therapy and remained persistent for at least 12 months.

Proportion and magnitude of dose escalation

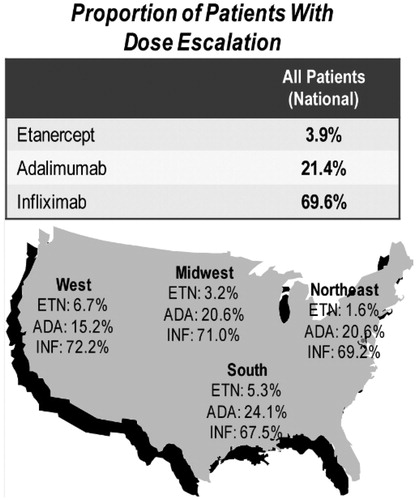

Using the average weekly dose method (i.e., average weekly dose compared to the recommended dose), nationally, 3.9% of etanercept, 21.4% of adalimumab, and 69.6% of infliximab patients experienced a dose escalation greater than the recommended starting label dose over the first 12 months after therapy initiation (). Dose escalation was significantly lower for etanercept compared with adalimumab and infliximab (p < 0.0001 for both). Nationally, the proportion of patients with the average dose exceeding the recommended starting dose by 130% was 0.5% of etanercept, 9.0% of adalimumab, and 36.1% of infliximab patients (p < 0.001, ). For each of the four US regions, there were significantly lower proportions of etanercept-treated patients with dose escalation (range from 1.6% in the Northeast to 6.7% in the West) compared with adalimumab (range: 15.2% in the West to 24.1% in the South) and infliximab (range: 67.5% in the South to 72.2% in the West); p < 0.05 for etanercept compared to both adalimumab and infliximab, ). The proportion of patients with an average dose exceeding the recommended starting dose by 130% was consistently lowest for etanercept and highest for infliximab for all four US census regions (p < 0.01, ).

Figure 1. Regional proportion and magnitude of dose escalation using the average weekly dose method among RA biologic-naïve patients persistent on TNF-blocker therapy for 12 months.

Table 2. National proportion and magnitude of dose escalation among RA biologic-naïve patients persistent on TNF-blocker therapy for 12 months for each dose escalation method.

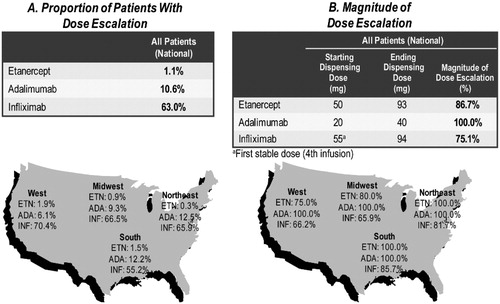

The average ending dispensed dose method provided a similar but slightly lower proportion of patients with dose escalation across the three TNF-blockers than the average weekly dose method; few etanercept patients (1.1%) experienced dose escalation compared with adalimumab (10.6%) and infliximab (63.0%) patients (p < 0.0001 for both) based on the comparison of ending dose to starting dose. Regionally, the proportion of patients with dose escalation was lowest for etanercept (0.3% in the Northeast to 1.9% in the West) followed by adalimumab (6.1% in the West to 12.5% in the Northeast), and highest for infliximab (55.2% in the South to 70.4% in the West) ().

Figure 2. Regional proportion and magnitude of dose escalation using the average ending dispensed dose method among RA biologic-naïve patients persistent on TNF-blocker therapy for 12 months.

With the average ending dose method, the 1.1% of etanercept patients with dose escalation had an average 87% increase in dose compared to the starting dose (from an average of 50 mg/week to 93 mg/week), while the 10.6% of adalimumab patients with dose escalation had a doubling of dose (from an average of 20 mg/week to 40 mg/per week) and the 63.0% of infliximab patients with dose escalation had an average 75% increase in dose (from an average of 55 mg/week to 94 mg/week) nationally. Among those with dose escalation, the magnitude of dose increase ranged from 75.0% in the West to 100% in the Northeast and South for etanercept, 100% in all four regions for adalimumab, and from 65.9% in the Midwest to 85.7% in the South for infliximab ().

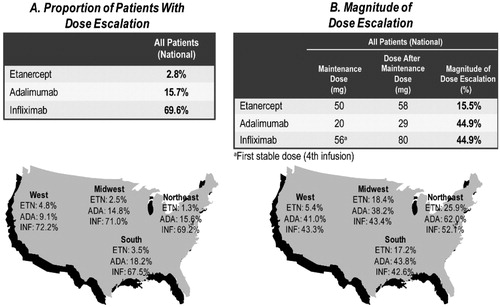

The average dose after maintenance dose method showed consistent patterns of dose escalation across the TNF-blockers, as was noted for the other two methods (). Etanercept had the lowest proportion of patients with escalation (2.8% of patients) compared with adalimumab (15.7%) and infliximab (69.6%) patients nationally (p < 0.0001 for both). A similar pattern of lowest proportions with dose escalation for etanercept and highest proportions for infliximab were observed across all four regions ().

Figure 3. Regional proportion and magnitude of dose escalation using the average dose after maintenance dose method among RA biologic-naïve patients persistent on TNF-blocker therapy for 12 months.

Of the 2.8% of etanercept patients experiencing dose escalation nationally, the magnitude of dose increase was 16% (from an average of 50 mg/week to 58 mg/week). Of the 15.7% of adalimumab patients experiencing dose escalation, the magnitude of dose increase was 45%. Of the 69.6% of infliximab patients experiencing dose escalation, the magnitude of dose increase was 45%. The pattern of the magnitude of dose increase among those with dose escalation was consistent across the four regions ().

Cost of TNF-blocker therapy per treated patient

Annual cost per treated patient which accounts for the variability in dose escalation, method of administration, and dosing schedules was lowest for etanercept ($19,690) compared with adalimumab ($23,020, p < 0.0001) and infliximab ($24,030, p < 0.0001) (). There were a total of 3826 infliximab infusions over the 12 months, 8.4 infusions per patient, for 454 patients. With the addition of drug administration fees (one in-office injection for etanercept and adalimumab and 2-hour infusion for each infliximab administration), the cost per treated patients was 17% higher for adalimumab and 29% higher for infliximab compared with etanercept.

Table 3. Cost of TNF-blocker therapy per treated RA patient.

Discussion

The present study provides current estimates of dose escalation, including drug utilization from 2005–2010, among the three most prescribed biologics for RA treatment. The study findings represent clinical practice after managed care organizations implemented cost containment strategies for biologic therapies. This is one of the few studies to provide regional estimates of dose escalation across the US. Regional dosing patterns were similar to national dosing patterns, with etanercept having the lowest and infliximab having the highest proportions of dose escalation consistently across the geographic regions. This is the first study to provide estimates for the magnitude of dose escalation among patients who initiated TNF blocker therapy at or above the recommended dose. These national and regional estimates may assist health plans to benchmark their dose escalation rates to the national and regional estimates from the LifeLink data as well as inform formulary decision-making.

Across all three methods of computing dose escalation, dose escalation proportions in the first 12 months after therapy initiation were significantly lower among RA patients treated with etanercept compared with patients treated with adalimumab and infliximab. Very few etanercept patients (<4%) experienced dose escalation, regardless of the method employed. However, the majority of infliximab patients (63–70%) had dose escalation and 11–21% of adalimumab patients had dose escalation within the first year of therapy. In general, the magnitude of the dose escalation was lowest among etanercept patients compared to adalimumab and infliximab patients. Both the average weekly dose method and the average dose after maintenance dose method showed that magnitude of dose escalation was lowest among etanercept and highest among infliximab patients, nationally and across all four geographic regions. With the average ending dispensed dose method, very few (1.1%) etanercept patients had an average 87% dose increase, while 11% of adalimumab patients had a doubling of the dose and 63% of infliximab patients had an average 75% dose increase.

The present study finding that proportions with dose escalation are higher among adalimumab and infliximab patients than among etanercept patients is consistent with previous investigations across different RA patient populations. Harrison et al.Citation18 found dose escalation rates of 1–3% for etanercept, 9–10% for adalimumab, and 24–26% for infliximab using the same database, but examining dosing patterns in 2004–2005. A recent study of RA patients in the MarketScan database (large employer-sponsored health plans) found that patients initiating etanercept (0.8–1.5%) had lower rates of dose escalation than patients initiating adalimumab (10.8–12.5%) or infliximab (16.4–42.5%) between 2005–2009, using different definitions of dose escalation than the present studyCitation31. Studies using US managed care databases for the period of 2002–2004 found dose escalation rates of ∼5–7% for etanercept and 9–21% for adalimumabCitation17,Citation24,Citation26,Citation27. A retrospective analysis using a large health plan database (Ingenix) for April 2007 through March 2009 found that 3% of etanercept patients increased their weekly dose from 50 mg to 100 mg, 13% of adalimumab patients increased their biweekly dose from 40 to 80 mg, and 39% of infliximab patients either added another vial or reduced the time between infusion administrations to <6 weeksCitation32. Some of the variation in the dose escalation estimates may be due to the method of calculating dose escalation, differences over time and in the population studied. Despite these differences, there is a consistent trend of higher rates of dose escalation among adalimumab and infliximab patients compared with etanercept patients. Dose escalation patterns in the present study are consistent with those described from 2004–2005 datasets, despite intensive cost management efforts from health plans in recent years.

For magnitude of dose escalation, most previous studies have provided only an estimate of the proportion of patients who had dose escalation and did not describe the size of the escalationCitation17,Citation18,Citation22,Citation33, and other investigators used a pre-defined percentage increase in doseCitation27. However, Bullano et al.Citation24, using the starting dose from the first prescription and not the first stable (maintenance) dose, showed that the average increase in dose was lowest for etanercept (4.1%) and highest for infliximab (17.4%) using a similar method to the present study’s average ending dispensed dose method.

In two recent RA European studies, higher dose escalation rates were observed among adalimumab and infliximab patients compared to etanercept patients, but changes in disease activity were similarCitation22,Citation33. Schabert et al.Citation34 also found similar disability outcomes among US patients in an RA registry treated with etanercept, adalimumab, or infliximab, even though self-reported dose escalations were observed significantly more often among infliximab and adalimumab patients than among etanercept patients. In a retrospective review of charts, Segal et al.Citation35 found that, although patients on etanercept were significantly less likely to have dose escalation compared with patients on adalimumab or infliximab, there was no significant difference in the percentage of responders between treatment group patients with or without dose escalation.

The present study found that cost of TNF-blocker therapy per treated patient was lowest with etanercept compared with adalimumab and infliximab; 17% lower cost over adalimumab and 29.5% lower cost over infliximab. This finding concurs with other studies that used 2004–2005 datasets; cost of TNF-blocker therapy was lowest among etanercept patientsCitation17,Citation18,Citation26. Other studies have shown that treatment groups with higher rates of dose escalation have increased therapy costs, whereas low population rates of dose escalation are associated with stable costsCitation24,Citation36. Additionally, several studies have shown that increasing the dose of a TNF-blocker beyond the minimum recommended dose increases the risk of adverse eventsCitation19–21, which add to the cost burden. With the consistent evidence indicating that dose escalation may be necessary to achieve equal clinical benefit and that additional cost is incurred for the TNF-blockers with the higher proportions with dose escalation, this should be taken into consideration while making formulary decisions.

A strength of this study is the use of several methods of calculating dose escalation that have been used in previous studies. Three methods of calculating dose escalation were used in this study because there is no standard, accepted method that has been used across studies. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages. The average weekly dose method uses the recommended label dose for comparison which provides a standard metric across TNF-blockers, but does not allow for clinical judgment for starting patients at higher than recommended doses. The average weekly dose method uses the average dose over the entire follow-up period, capturing the overall utilization. The average ending dispensed dose method ignores drug utilization patterns in between the first stable dose and last dose, but this method was enhanced for the present study by using the first stable dose for infliximab rather than the first dispensed dose. The average dose after maintenance dose method combines the best attributes from the other methods since it captures the actual drug utilization over the entire follow-up period and uses the maintenance dose (stable dose) as the comparison rather than the label dose, thus using real-world practice patterns.

The study was subject to several limitations. The exclusion of patients not on continuous TNF-blocker therapy limits the generalizability of the results; however, results from a recent studyCitation32 in another large managed care health plan showed that drop-out rates were similar across etanercept (20%), adalimumab (17%), and infliximab (24%) within the first 12 months of initiating biologic therapy. In the present study, 48% of etanercept, 52% of infliximab, and 47% of adalimumab patients were persistent on therapy for 12 months, suggesting that this exclusion did not bias the results. The population in this study comprised RA patients newly treated with a biologic TNF-blocker who were continuously enrolled in a commercial health insurance plan; results, therefore, may not be generalizable to other populations such as Medicare patients or uninsured populations. Costs were calculated using the WAC and mean dose rather than the paid amount on the pharmacy claim, so health plan-specific price discounts and contracting are not included in the costs. Based on the study time period and lag in adjudicated claims data, there were an insufficient number of patients persistent on other biologic therapies (e.g., certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab) for 12 or more months to include in the analysis.

In conclusion, in this retrospective study, national TNF-blocker dose escalation proportions and magnitudes were lowest among etanercept patients compared with adalimumab and infliximab patients. Regional estimates of dose escalation and magnitude of the increase in dose consistently showed the same pattern of lower estimates for etanercept and higher estimates for adalimumab and infliximab. Mean annual cost per treated patient was also lowest for etanercept compared to adalimumab and infliximab (etanercept had a 17% cost advantage compared to adalimumab and a 30% cost advantage compared to infliximab). Health plan administrators may want to consider these dosing patterns and cost differentials when making formulary decisions regarding TNF-blocker therapy.

Transparency

Declaration of funding:

This research was funded by Immunex, a wholly owned subsidiary of Amgen, Inc., and by Wyeth, which was acquired by Pfizer. The sponsor had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to publish, except through the author, SRG, who is an employee of Amgen, Inc. ATG provided substantial contribution to the acquisition of data and analysis and interpretation of the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the manuscript. SRG provided substantial contribution to the conception and design of the study, interpretation of the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the manuscript. KMF provided substantial contribution to the design of the study and analysis, oversaw the analysis, provided data interpretation, wrote the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript. TWS provided substantial contribution to the data analysis and interpretation of the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the manuscript. MWP provided substantial contribution to data analysis and interpretation of the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Declaration of financial/other relationships:

ATJ, TWS, and MWP received research funds from Amgen, Inc. to conduct the study; SRG is an employee and stockholder of Amgen, Inc., and KMF received research funds from Amgen, Inc.

Acknowledgments

Poster presented at the 2011 ACR/ARHP Annual Scientific Meeting, Chicago, IL, November 4–9, 2011. No assistance in the preparation of this article is to be declared.

References

- Ritchlin CT. Mechanisms of erosion in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2004;31:1229-37

- Cook AD, Visvanathan K. Molecular targets in immune-mediated diseases: focus on rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin Therap Targets 2004;8:375-90

- Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2010;376:1094-108

- Kalyoncu U, Dougados M, Daures JP, et al. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in recent trials in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:183-90

- Isik A, Koca SS, Ozturk A, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2007;26:872-8

- Sheehy C, Murphy E, Barry M. Depression in rheumatoid arthritis – underscoring the problem. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:1325-7

- Yelin E. Work disability in rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2007;19:91-6

- Birnbaum H, Pike C, Kaufman R, et al. Societal cost of rheumatoid arthritis patients in the US. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:77-90

- Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan V, Huang XY, et al. Influence of rheumatoid arthritis on employment, function, and productivity in a nationally representative sample in the United States. J Rheumatol 2010;37:544-9

- Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patient with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:26-37

- Breedveld F, Emery P, Ferraccioli G, et al. Clinical response and remission at 12, 24, and 52 weeks with the combination of etanercept and methotrexate in the treatment of early active rheumatoid arthritis in the COMET trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67(2 Suppl):1

- Van der Heijde D, Klareskog L, Landewe R, et al. Disease remission and sustained halting of radiographic progression with combination etanercept and methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:3928-39

- Emery P, Breedveld FC, Hall S, et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomized, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet 2008;372:375-82

- HUMIRA (adalimumab) PI, 03/2011. Abbott Laboratories

- REMICADE (infliximab) PI, 04/2011. Centocor Ortho Biotech Inc

- ENBREL (etanercept) PI, 05/2011. Manufactured by Immunex Corporation. Marketed by Amgen Inc. and Pfizer Inc.

- Gu NY, Huang XY, Fox KM, et al. Claims data analysis of dosing and cost of TNF antagonists. Am J Pharm Benef 2010;2:351-9

- Harrison DJ, Huang X, Globe D. Dosing patterns and costs of tumor necrosis factor inhibitor use for rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Health- Syst Pharm 2010;67:1281-7

- Alonso-Ruiz A, Pijoan JI, Ansuategui E, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha drugs in rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and safety. BMC Musculoskel Disord 2008;9:52

- Zintzaras E, Dahabreh IJ, Giannouli S, et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of dosage regimens. Clin Therap 2008;30:1939-55

- Perdriger A. Infliximab in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Biologics 2009;3:183-91

- Moots RJ, Haraoui B, Matucci-Cerinic M, et al. Differences in biologic dose-escalation, non-biologic and steroid intensification among three anti-TNF agents: evidence from clinical practice. Clin Exper Rheumatol 2011;29:26-34

- Gilbert TD, Smith D, Ollendorf DA. Patterns of use, dosing, and economic impact of biologic agent use in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskel Disord 2004;5:36

- Bullano MF, McNeeley BJ, Yu YF, et al. Comparison of costs associated with the use of etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Manag Care Interf 2006;19:47-53

- Wu E, Chen L, Birnbaum H, et al. Retrospective claims data analysis of dosage adjustment patterns of TNF antagonists among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Curr Med Res Opin 2008;24:2229-40

- Ollendorf DA, Klingman D, Hazard E, et al. Differences in annual medication costs and rates of dosage increase between tumor necrosis factor-antagonist therapies for rheumatoid arthritis in a managed care population. Clin Therap 2009;31:825-35

- Huang X, Gu NY, Fox KM, et al. Comparison of methods for measuring dose escalation of the subcutaneous TNF antagonists for rheumatoid arthritis patients treated in routine clinical practice. Curr Med Res Opin 2010;26:1637-45

- Flood J, Mihalik C, Fleming RR, et al. The use of therapeutic interchange for biologic therapies. Managed Care 2007;16:51-62

- Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, et al. Mean body weight, height, and body mass index, United States 1960–2002. Vital Health Stat 2004;347:1-17

- First DataBank. AnalySource Online. Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC). http://www.fdbhealth.com/fdb-medknowledge-drug-pricing. Accessed September 11, 2012

- Bonafede MK, Gandra SR, Fox KM, et al. Tumor necrosis factor- blocker dose escalation among biologic naïve rheumatoid arthritis patients in commercial managed care plans in the two years following therapy initiation. J Med Econ 2012;15:1-9

- Khanna D, Cyhaniuk A, Bedenbaugh A. Use of TNF inhibitors in the US: Utilisation patterns and dose escalation from a retrospective US RA population [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70(3 Suppl):197

- Blom M, Kievit W, Kuper HH, et al. Frequency and effectiveness of dose increase of adalimumab, etanercept, and infliximab in daily clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res 2010;62:1335-41

- Schabert VF, Bruce B, Ferrufino CF, et al. Disability outcomes and dose escalation in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor blockers: a comparative effectiveness analysis [abstract PMS2]. Value Health 2010;13:A302

- Segal SD, Power DJ, Smith DB, et al. Comparative effectiveness analysis of TNF blockers in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients in US community practice [abstract]. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70(3 Suppl):252

- Etemad L, Yu EB, Wanke LA. Dose adjustment over time of etanercept and infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Manag Care Interf 2005;18:21-7