Abstract

Objectives:

To compare the healthcare costs of patients with overactive bladder (OAB) who switch vs persist on anti-muscarinic agents (AMs), describe resource use and costs among OAB patients who discontinue AMs, and assess factors associated with persisting vs switching or discontinuing.

Methods:

OAB patients initiating an AM between January 1, 2007 and March 31, 2012 were identified from a claims database of US privately insured beneficiaries (n ≈ 16 million) and required to have no AM claims in the 12 months before AM initiation (baseline period). Patients were classified as persisters, switchers, or discontinuers, and assigned a study index date based on their AM use in the 6 months following initiation. Baseline characteristics, resource use, and costs were compared between persisters and the other groups. Resource use and costs in the 1 month before and 6 months after the study index date (for switchers, the date of index AM switching; for persisters, a randomly assigned date to reflect the distribution of the time from AM initiation to switching among switchers) were also compared between persisters and switchers in unadjusted and adjusted analyses. Factors associated with persisting vs switching or discontinuing were assessed.

Results:

After controlling for baseline characteristics and costs, persisters vs switchers had significantly lower all-cause and OAB-related costs in both the month before (all-cause $1222 vs $1759, OAB-related $142 vs $170) and 6 months after the study index date (all-cause $7017 vs $8806, OAB-related $642 vs $797). Factors associated with switching or discontinuing vs persisting included index AM, younger age, and history of UTI.

Conclusion:

A large proportion of OAB patients discontinue or switch AMs shortly after initiation, and switching is associated with higher costs.

Introduction

Overactive bladder (OAB) is a chronic condition and, in the US, as many as 36% of adults at least 40 years of age experience OAB symptoms at least some of the timeCitation1. OAB symptoms include urinary urgency, with or without urge incontinence, usually with frequency and nocturia, in the absence of pathologic or metabolic conditions that might explain these symptomsCitation2. These symptoms, particularly urge incontinence, often meaningfully reduce daily quality-of-life in patientsCitation3. OAB carries a large economic burden in the US; total annual OAB-associated costs were estimated in 2007 to be $65.9 billion, of which $49.1 billion were direct medical costs, $2.3 billion were direct non-medical costs, and $14.6 billion were indirect costs from work productivity lossCitation4. The economic burden of much routine care for OAB (e.g., laundry, pads/diapers, etc.) is borne primarily by patients, and can be several hundred dollars annuallyCitation5.

Treatments for OAB are aimed at reducing the frequency and severity of symptoms, and options include behavioral therapy, such as bladder training and fluid management, and pharmacologic therapyCitation6. Following first-line behavioral therapy, the American Urological Association (AUA) recommends the use of anti-muscarinic agents (AMs), an anti-cholinergic class of drugs that includes darifenacin, fesoterodine, oxybutynin, solifenacin, tolterodine, trospium, and oral β3-adrenoceptor agonistsCitation6. Use of AMs is limited by a number of contraindications, including urinary retention, specific disorders of function of the stomach, and narrow angle glaucoma, as well as by the presence of side-effects such as dry mouth and constipationCitation5.

Multiple studies suggest that the majority of OAB patients discontinue or switch AM therapy after a few weeks or monthsCitation7–10. Studies have shown that many patients fill only one AM prescription before discontinuing therapy, with the proportion of patients filling only one prescription ranging from 33–68% varying with type of insurance coverage population analyzedCitation8,Citation10,Citation11. Patients discontinue treatment for multiple reasons. In a survey of patients who discontinued at least one OAB medication in the previous 12 months, the top five reasons for discontinuation were unmet treatment expectations (46%), switch to a new medication (25%), the patient learned to get by without medication (23%), side effects (21%), and a medical professional’s instructions (18%). Moreover, 15% of patients reported that bladder symptoms had stopped or the bladder problem had been curedCitation7. In addition, there appear to be some differences in persistence by AM and formulation (e.g., immediate release [IR] vs extended release [ER])Citation8,Citation12,Citation13.

Despite multiple sources reporting high rates of switching and discontinuation of AMs, there is limited information regarding the impact of switching AMs on healthcare resource use and costs. In addition, in order to help patients best manage their OAB, there is a need to improve the understanding of factors associated with non-persistence on therapy. The objectives of this study were to characterize impact of switching vs persisting on AMs on healthcare resource use and costs; to describe resource use and costs among patients who discontinue AMs; and to assess factors associated with persisting vs switching or discontinuing.

Methods

Database

This study utilized a database of de-identified commercial administrative claims (OptumHealth Reporting and Insights, formerly Ingenix Employer Solutions). The database has enrollment and demographic information, pharmacy, and medical claims for ∼16 million privately insured lives from January 1, 1999 to March 31, 2012 covered by numerous insurer plans from 60 US-based companies in a variety of industries. Medicaid and Medicare claims are not included in the database.

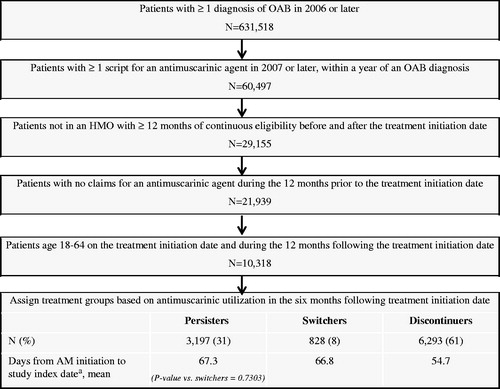

Sample selection

Patients were included in the sample if they had at least one diagnosis of OAB (ICD-9 codes 596.51, 788.3 [except 788.32], 788.4) in 2006 or later and had at least one claim for an AM in 2007 or later and within a year after an OAB diagnosis. The first AM script in 2007 or later was defined as the treatment initiation date. Patients were also required to have at least 12 months of continuous eligibility in a non-HMO health plan prior to (baseline period) and following the treatment initiation date, no claims for an AM during the 12 months prior to the treatment initiation date, and be aged 18–64 on the treatment initiation date and the following 12 months. (See for sample selection, n = 10,318). Patients with HMO coverage were excluded because they have incomplete information about resource use and costs due to missing claims for out-of-network services and missing insurer payment information.

Figure 1. Sample selection. aFor switchers the study index date was the date of index AM switching within 6 months after AM initiation; for persisters, the study index date was randomly assigned to reflect the distribution of time from AM initiation to the study index date for switchers; for discontinuers the study index date was the date of index AM discontinuation.

Patients were then classified into one of three mutually exclusive groups and assigned study period index dates based on their AM use in the 6 months following the treatment initiation date. Switchers were defined as patients who switched from the index AM within the first 6 months after the treatment initiation date (with a gap of ≤60 days between the end of the day supply [recorded in the pharmacy claims] of the index AM and the new AM); the study index date was defined as date of switching. Discontinuers were defined as patients who discontinued the index AM, defined as a gap of at least 60 days between refills within the first 6 months after the treatment initiation date; the study index date was defined as the date of discontinuation. Lastly, patients who did not switch or discontinue the index AM during the first 6 months after the treatment initiation date were defined as persisters; these patients were randomly assigned a study index date to reflect the distribution of the time from AM initiation to switching among switchers. This was accomplished by randomly selecting with replacement a time from treatment initiation to study index date for each persistent patient from the times to study index date calculated among switchers (see ). The choice of a 6-month period after the treatment initiation date in order to classify patients based on AM use and the duration of the gap in medication supply used to define switching or discontinuation were based on an initial evaluation of the data. The initial evaluation showed that most patients had index AM claims with 30 or 90 days supply (75th percentile was 30 days and 90th and 99th percentiles were 90 days), that the gap between refills for index AM was often less than 30 days, and that 85% of patients who switched and 87% of patients who discontinued index AM therapy within 1 year after initiation did so within the first 6 months.

Measures

Baseline characteristics (e.g., age, sex, region, insurance type, Charlson Comorbidity IndexCitation14,Citation15 [CCI], and selected OAB-associated comorbidities and contraindications), baseline resource use (e.g., inpatient, emergency department [ED], outpatient, and other visits), and baseline medical, pharmacy, and total costs (defined as insurer payments to providers) were assessed over the year prior to the treatment initiation date using all medical and pharmacy claims. All-cause and OAB-related resource use and costs during the 1 month before and the 6 months after the study index date were assessed and compared between persisters and switchers to evaluate the impact of switching on resource use and costs. A 6-month follow-up period was selected because published studies suggest that a high proportion of patients discontinue therapy over timeCitation8,Citation10,Citation11; over a longer follow-up period (e.g., a year) more patients would have discontinued, obscuring the effect of switching relative to persistence. Resource use was considered to be OAB-related if the claim carried a diagnosis of OAB (in either of the two diagnosis code fields provided in the database) or was for OAB-related services (i.e., sacral neuromodulation, peripheral tibial nerve stimulation, use of intradetrusor onabotulinumtoxinA, and augmentation cystoplasty or urinary diversion). Costs were considered OAB-related if they were for OAB-related resource use or for use of AMs. All costs were inflated to and are reported in 2012 USD, the last year covered by the data.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics, resource use, and costs were compared separately for persisters vs switchers and persisters vs discontinuers. Unadjusted all-cause and OAB-related resource use and costs during the 1 month before and the 6 months after the study index date were compared between persisters and switchers to evaluate the impact of switching on resource use and costs. Chi-squared tests were used to compare categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare continuous variables. Comparisons were not made between persisters and discontinuers during the 1 month before and the 6 months after the study index date due to an a priori expectation that discontinuers represented a heterogeneous group of patients which could include patients with mild OAB that could be managed without medication, patients who had symptoms resolve independent of the medication, patients who were intolerant to medication, or patients who were reluctant to take any medicationCitation7.

Regression-adjusted total and pharmacy costs for the 1 month before and the 6 months after the study index date were also estimated and compared between persisters and switchers using generalized linear models (GLMs) with log link and gamma distribution for the error term. The multivariate models adjusted for age, sex, region, insurance type, baseline CCI, select baseline OAB-associated comorbidities, and anti-muscarinic contraindications with prevalence of at least 5% in one of the groups, and baseline logged costs (e.g., log of baseline all-cause costs for models of study period all-cause costs and log of baseline OAB-related costs for models of study period OAB-related costs). Because a high proportion of patients had medical costs equal to 0, regression-adjusted medical costs were estimated using two-part models, controlling for the same covariates as the one-part models. A logistic regression first estimated the probability of having non-zero costs, then a GLM estimated the conditional costs among patients with non-zero costs. The mean predictions from the logistic and GLM regressions were multiplied to generate the mean expected medical costs. p-values and standard errors were obtained using bias-adjusted bootstrapping with replacement over 1000 iterations.

An additional exploratory analysis examined factors associated with persistence vs switching or discontinuation, using a multinomial logit model with persistence as the reference value for the dependent variable. The multivariate model included as explanatory variables index AM, age, sex, region, insurance type, baseline CCI, select baseline OAB-associated comorbidities, and anti-muscarinic contraindications with prevalence of at least 5% in one of the groups, and log of baseline OAB-related costs.

Results

Among patients who met the study criteria, 3197 (31.0%) persisted on index AM therapy, 828 (8.0%) switched to another AM, and 6293 (61.0%) discontinued therapy within 6 months after AM initiation; the mean time to switching was 66.8 days, while the mean time to discontinuation was 54.7 days (see ). A total of 70.0% of discontinuers (42.7% of patients overall) discontinued their index AM after a single prescription.

Persisters were on average 53.4 years of age, compared with 52.6 for switchers (p = 0.40 vs persisters) and 50.5 for discontinuers (p < 0.001), and approximately one quarter of patients in each group were male. Persisters had a mean CCI that was not significantly different than that among switchers (0.80 vs 0.85) and a significantly higher CCI than discontinuers (0.74, p < 0.001). Over one quarter of patients in each group had diagnoses for falls, fractures, or related injuries during the baseline period. Significantly fewer persisters had a baseline period diagnosis of a urinary tract infection (UTI) than either switchers or discontinuers (26.6% vs 33.9% and 31.7%, respectively, both p < 0.001) (see ).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics, resource use, costs, and anti-muscarinic agent initiated among OAB patients.

Most patients initiated AM therapy on solifenacin, tolterodine, and oxybutynin; persisters were more likely than switchers or discontinuers to have initiated on solifenacin (30.1% vs 19.7% and 24.5%, respectively, both p < 0.001) and less likely to have initiated on oxybutynin (22.6% vs 29.6% and 30.6%, respectively, both p < 0.001). Persisters had lower baseline all-cause costs than switchers ($15,096 vs $17,512, p < 0.001), driven by lower baseline medical costs, but baseline OAB-related costs were similar. Persisters had higher baseline all-cause and OAB-related costs than discontinuers ($15,096 vs $13,831; $469 vs $420, respectively, both p < 0.001).

In the month prior to the study index date, both all-cause and OAB-related resource use were generally substantially lower among persisters than switchers, including the proportion of patients with all-cause inpatient visits (2.4% vs 5.1%, p < 0.001), all-cause outpatient visits (68.8% vs 82.0%, p < 0.001), or OAB-related outpatient visits (20.3% vs 39.9%, p < 0.001). Correspondingly, all-cause and OAB-related total costs were also lower among persisters ($1247 vs $2056 and $143 vs $175, respectively, both p < 0.001), driven by lower medical costs ().

Similar trends were observed in the 6 months following the study index date. Fewer persisters had an all-cause inpatient visit compared with switchers (9.9% vs 14.9%, p < 0.001). OAB-related resource use was also lower among persisters, including the proportion of patients with OAB-related outpatient visits (29.4% vs 43.0%, p < 0.001). Total all-cause costs were $7321 among persisters and $9864 among switchers (p < 0.001), driven by lower medical costs, primarily lower outpatient costs which accounted for almost half ($1091) of the medical cost differential ($2388) between persisters and switchers. OAB-related pharmacy costs were higher among persisters, driven by the greater days of supply of AMs. However, OAB-related medical costs were significantly lower among persisters, leading to lower total OAB-related costs ($628 vs $882, p = 0.003) ().

Discontinuers, while not statistically compared with persisters or switchers, generally had resource use and costs more consistent with switchers in the 1 month prior to the study index date. However, following the study index date, discontinuers generally had substantially lower OAB-related resource and costs than either switchers or persisters. In the 6 months following discontinuation, only 22.2% of discontinuers had an OAB-related outpatient visit. Discontinuers also had on average only 9.3 days supply of AMs and mean OAB-related costs of $198.

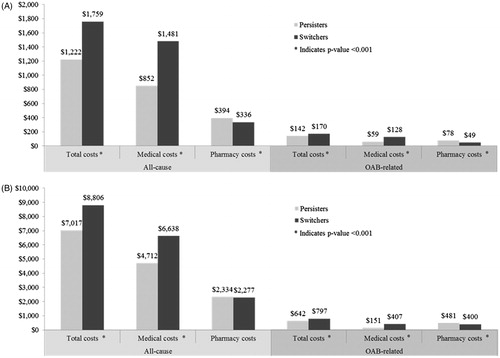

After adjusting for possible confounders, persisters had significantly lower total costs in the month prior to the study index date (all-cause $1222 vs $1759; OAB-related $142 vs $170, both p < 0.001), driven by lower medical costs. Persisters also had lower total costs during the 6 months after the study index date, driven by lower medical costs (all-cause total costs $7017 vs $8806; OAB-related total costs $642 vs $797, both p < 0.001). Persisters had significantly higher all-cause and OAB-related pharmacy costs in the month prior to the study index date, likely driven by the greater days of supply of AMs (see ).

Figure 2. Comparison of adjusted costs between persisters and switchers. (A) Adjusted costs in the 1 month before the study index datea. (B) Adjusted costs in the 6 months after the study index datea. aFor switchers the study index date was the date of index AM switching within 6 months after AM initiation; for persisters, the study index date was randomly assigned to reflect the distribution of time from AM initiation to the study index date for switchers.

In the exploratory analysis, only younger age, history of UTI at baseline, and index AM were significantly associated with switching vs persistence. Compared with patients initiating on solifenacin, patients initiating on all other AMs except darifenacin were significantly more likely to switch than persist. Having tolterodine and oxybutynin vs solifenacin as the index AM was also significantly associated with discontinuation vs persistence. Other factors significantly associated with discontinuation vs persistence included younger age, male sex, living in the south or unknown region vs midwest, insured under a point of service plan vs a preferred provider organization, history of UTI, and lower log of baseline OAB-related costs (see ).

Table 2. Unadjusted resource use and costs in the 1 month before and 6 months after the study index datea.

Table 3. Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) for factors associated with persistence.

Discussion

In general, patients who switched AMs within 6 months after initiation had higher costs immediately before and after switching compared with persisters. In terms of resource utilization and costs, discontinuers were more similar to switchers than persisters in the month prior to discontinuation, but had lower OAB-related resource use and costs than either persisters or switchers in the 6 months after the study index date. Index AM other than solifenacin, younger age, and history of UTI seem to be the factors most strongly associated with non-persistence.

The persistence rates observed in this study (31.0% at 6 months) are generally consistent with those available in the published literature, which range from 10–46% and 18–41% at 6 months for individual agents and overallCitation12,Citation16. We observed slightly fewer therapy switches (8.0% of patients) than D’Souza et al.Citation8 (13.3%), but slightly more than observed by Chancellor et al.Citation11 (5.8%); these discrepancies are likely due to the definition of a switch: we required a switch to occur within 60 days of the end of an index AM claim, while D’Souza et al. assessed any therapy or formulation switch within a 1-year follow-up period and Chancellor et al. required the switch to occur within 45 days of the end of an index AM claim. The mean time to switching and discontinuation were 66.8 days and 54.7 days, respectively, or ∼2 months, which falls between the median and mean reported by D’Souza et al.Citation8 A total of 42.7% of patients never refilled, which matches closely to the 33–45% reported in studies among privately insured patientsCitation8,Citation10.

The adjusted results indicate that patients who persist on their index AM for at least 6 months have significantly lower total costs than patients who switch AMs, driven by lower medical (especially outpatient) costs. This finding may be indicative of unmet need; if switchers continue to experience OAB symptoms or develop treatment side-effects, they may seek additional care and switch AMs. This explanation is consistent with literature suggesting that the primary reason for AM switching is unmet treatment expectationsCitation7,Citation9. However, Siddiqui et al.Citation17 observed patients who were not satisfied with their index AM but persisted on therapy, and found that these patients generally had fewer visits to clinicians over the previous year, suggesting that they may simply be less likely to seek care. In the current study, it is possible that some of the persisters may have sought less care and incurred lower costs, despite continuing to experience symptoms, but this bias is unlikely given that the regressions controlled for baseline costs, which were used as a proxy for disease severity and propensity to seek medical care.

As expected, discontinuers had different characteristics than persisters and switchers. Because of their low baseline and study period resource use and costs to third-party payers, discontinuers most likely represent a heterogeneous group of patients with milder OAB amenable to non-pharmacologic therapy, patients less likely to seek medical care, patients whose condition symptomatology fluctuates over time, or patients who discontinue after experiencing side-effects or lack of symptom improvement. As noted by Chancellor et al.Citation11, use of AMs on an as-needed basis may be classified as discontinuation in claims data analyses; that study observed both AM re-initiation and permanent discontinuation of AMs within 2 years. Our analysis did not assess re-initiation rates, but the low OAB-related resource use and low days supply of AMs during the 6 months following discontinuation suggest that patients were generally not utilizing OAB-related care following AM discontinuation. Therefore, it was not appropriate to compare them to patients who were actively receiving OAB treatment.

Compared with solifenacin, every AM except darifenacin was significantly associated with a higher likelihood to switch than persist; only tolterodine and oxybutynin were significantly associated with discontinuation vs persistence. The results of this study are consistent with other findings. The recent review by Veenboer and BoschCitation12 noted that oxybutynin use was significantly associated with non-persistence in six studies, and Wagg et al.Citation13 found that, on average, patients remained on solifenacin therapy for 187 days, at least 30 days longer than any other AM. This evidence suggests that the selection of initial AM therapy may be an important factor for persistence; the relationship may be mediated by efficacy or tolerability, as solifenacin has been shown to have better efficacy than tolterodine and cause less dry mouth than oxybutyninCitation18,Citation19. Another notable finding from the exploratory analysis was that lower baseline OAB-related costs (which could be a proxy for disease severity and/or propensity to seek medical care) were significantly associated with discontinuation vs persistence; however, baseline OAB-related costs had no significant association with switching vs persistence.

This analysis is subject to the typical limitations of administrative claims data, including the accuracy of recorded diagnoses, procedures, amounts and duration of prescriptions filled, and costs. In addition, clinical response to AM therapy and symptom reduction could not be observed in the claims data, and reasons for switching or discontinuing are not known. Thus, it is likely that not all factors associated with non-persistence could be identified in this claims study. The analysis also did not assess formulations of AMs (i.e., IR vs ER), dosing schedules, or side-effects of treatment that may have impacted persistence or healthcare resource useCitation8.

Because OAB-related costs were estimated using claims with OAB diagnosis code, it is likely that these costs were under-estimated; patients may receive OAB-related care when treated for other conditions without a recorded OAB diagnosis code by the physician (only up to two diagnosis codes were provided in the claims data). However, the magnitude of under-estimation is likely similar among persisters, switchers, and discontinuers. Additionally, this study assessed costs from the perspective of third-party payers and, therefore, did not capture the OAB-related costs borne by the patients for routine care, which can be substantialCitation5.

The database covers only privately insured patients and may not be geographically representative of the whole US. Additionally, the analysis excluded patients over the age of 65 who were eligible for Medicare. As such, the results of the study may not be generalizable to other populations.

Conclusions

A high proportion of patients discontinue or switch AMs early after initiation, and switching vs persisting is associated with higher all-cause and OAB-related costs. New therapy options with better tolerability profile could provide an alternative for patients whose needs are not being met with available AMs.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

Funding for this study was provided by Astellas Scientific & Medical Affairs, Inc., Northbrook, IL, USA.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

JI, EHL, RS, and HB are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., which received funding from Astellas Scientific & Medical Affairs, Inc. to conduct the research. TB is an employee of Astellas Scientific & Medical Affairs, Inc. JME Peer Reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Fitzmartin, PhD, employee of Astellas Scientific & Medical Affairs at the time of the study, for his input on the study design and interpretation of findings.

References

- Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Vats V, et al. National community prevalence of overactive bladder in the United States stratified by sex and age. Urology 2011;77:1081–7

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology 2003;61:37–49

- Shah S, Nitti VW. Defining efficacy in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome. Rev Urol 2009;11:196–202

- Ganz ML, Smalarz AM, Krupski TL, et al. Economic costs of overactive bladder in the United States. Urology 2010;75:526–32

- Coyne KS, Wein A, Nicholson S, et al. Economic burden of urgency urinary incontinence in the United States: a systematic review. J Manag Care Pharm 2014;20:130–40

- American Urological Association (AUA). Diagnosis and treatment of overactive bladder (non-neurogenic) in adults. AUA/SUFU guideline. Linthicum, MD: American Urological Association, May 2014. Available at: https://www.auanet.org/common/pdf/education/clinical-guidance/Overactive-Bladder.pdf. Accessed July 10, 2014

- Benner JS, Nichol MB, Rovner ES, et al. Patient reported reasons for discontinuing overactive bladder medication. BJU Int 2010;105:1276–82

- D’Souza AO, Smith MJ, Miller LA, et al. Persistence, adherence, and switch rates among extended-release and immediate-release overactive bladder medications in a regional managed care plan. J Manag Care Pharm 2008;14:291–301

- Schabert VF, Bavendam T, Goldberg EL, et al. Challenges for managing overactive bladder and guidance for patient support. Am J Manag Care 2009;15(4 Suppl):S118–22

- Shaya FT, Blume S, Gu A, et al. Persistence with overactive bladder pharmacotherapy in a Medicaid population. Am J Manag Care 2005;11(4 Suppl):S121–9

- Chancellor MB, Migliaccio-Walle K, Bramley TJ, et al. Long-term patterns of use and treatment failure with anticholinergic agents for overactive bladder. Clin Ther 2013;35:1744–51

- Veenboer PW, Bosch JL. Long-term adherence to antimuscarinic therapy in everyday practice: a systematic review. J Urol 2014;191:1003-8

- Wagg A, Compion G, Fahey A, et al. Persistence with prescribed antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder: a UK experience. BJU Int 2012;110:1767–74

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83

- Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis J. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:1075–9.

- Gopal M, Haynes K, Bellamy SL, et al. Discontinuation rates of anticholinergic medications used for the treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms. Obstet Gynecol 2008;112:1311–18

- Siddiqui E, Anderson P, Jackson J, et al. Comparison of overactive bladder patients who switch between antimuscarinic therapies with those who persist on the same therapy in the absence of improved outcomes: results of a cross-sectional study in 4 European countries. Poster presented at 42nd Annual Meeting of the International Continence Society, Beijing, China, October 15–19, 2012

- Chapple CR, Martinez-Garcia R, Selvaggi L, et al. A comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of solifenacin succinate and extended release tolterodine at treating overactive bladder syndrome: results of the STAR trial. Eur Urol 2005;48:464–70

- Herschorn SL, Stothers L, Carlson K, et al. Tolerability of 5 mg solifenacin once daily versus 5 mg oxybutynin immediate release 3 times daily: results of the VECTOR trial. J Urol 2010;183:1892–8