Abstract

Objective:

The past few decades have been marked by a bold increase in national health spending across the globe. Rather successful health reforms in leading emerging markets such as BRICS reveal a reshaping of their medical care-related expenditures. There is a scarcity of evidence explaining differences in long-term medical spending patterns between top ranked G7 traditional welfare economies and the BRICS nations.

Methods:

A retrospective observational study was conducted on a longitudinal WHO Global Health Expenditure data-set based on the National Health Accounts (NHA) system. Data were presented in a simple descriptive manner, pointing out health expenditure dynamics and differences between the two country groups (BRICS and G7) and individual nations in a 1995–2013 time horizon.

Results:

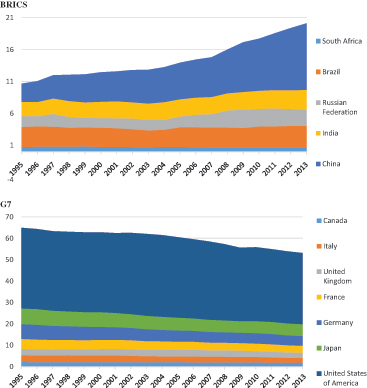

Average total per capita health spending still remains substantially higher among G7 (4747 Purchase Power Parity (PPP) $PPP in 2013) compared to the BRICS (1004 $PPP in 2013) nations. The percentage point share of G7 in global health expenditure (million current PPP international $US) has been falling constantly since 1995 (from 65% in 1995 to 53.2% in 2013), while in BRICS nations it grew (from 10.7% in 1995 to 20.2% in 2013). Chinese national level medical spending exceeded significantly that of all G7 members except the US in terms of current $PPP in 2013.

Conclusions:

Within a limited time horizon of only 19 years it appears that the share of global medical spending by the leading emerging markets has been growing steadily. Simultaneously, the world’s richest countries’ global share has been falling constantly, although it continues to dominate the landscape. If the contemporary global economic mainstream continues, the BRICS per capita will most likely reach or exceed the OECD average in future decades. Rising out-of-pocket expenses threatening affordability of medical care to poor citizens among the BRICS nations and a too low percentage of GDP in India remain the most notable setbacks of these developments.

Introduction

Healthcare devoted share of gross national income (GNI) has begun to grow steadily in most industrialized nations since the 1960s. This change has been reflected as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as well as per capita spendingCitation1. Such a dominating trend expanded to public and private medical spending, governmental resources and out-of-pocket consumption by citizens and households alike. There are several key drivers of this accelerated growth, with medical innovation, rising public expectations, and extended longevity among the major ones. Population agingCitation2 and blossoming of prosperity diseases had their shy roots more than a century ago, but have become an increasingly difficult burden for most national health systems over the past few decadesCitation3. All of these aforementioned changes began among developing world regions with a significant historical delay. This was the case mostly due to their respectively younger populationsCitation4 and lower incidence and prevalence of major non-communicable diseasesCitation5. We decided to compare dynamics of national healthcare expenditures among the prime examples of traditional market economies and top tier emerging marketsCitation6. As a representative of Organization for Economic and Social Development (OECD) we decided to observe the G7 countries; US, Japan, Germany, UK, France, Italy and Canada. As representatives of the fastest developing emerging markets we decided to observe the BRICS countries; Brazil, Russia, India, Peoples Republic of China and South AfricaCitation7. This brief report presents a novel insight into comparative medical spending dynamics of G7 and Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa (BRICS) over the past two decades. The aim of the paper is to reveal some surprising changes in the global health spending landscape and lay grounds for possible future forecasts.

Methods

Large international datasets reported by the national authorities to the WHO Global Expenditure DatabaseCitation8 have been used for a selected set of 12 countries and time horizon 1995–2013. Establishment and systematic pursuit of the National Health Accounts system worldwide dates back to 1995. The latest official release for almost all UN members present in this registry belong to 2013. The historical time horizon 1995–2013 was, thus, selected to reach as deep into the past as officially released data could allow. In order to avoid difficulties imposed by diverse exchange rates of national currencies, out of the variety of currency units offered by WHO Global Expenditure DB three were considered the most appropriate to allow greater international comparability. These three currency units used to present health expenditure data were constant 2005 US$, current US$ and current $PPP. The last one, international $ calculated on a purchase power parity basis, is particularly helpful when comparing high-income and developing economies due to their distinctively different civil purchasing powerCitation9. Therefore, PPP instead of nominal US$ values were used in along with calculations of the share of individual nations in global health expenditures. Simple descriptive statistics measures such as mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum values were selected instead of confidence interval due to the small sample size (five and seven countries, respectively) in data presentation and interpretation. Ethics committee approval was not applicable in this study due to the fact that it presents retrospective database research of the national level annual data presenting a population average. Discussion on the official data was accompanied with a concise literature review in order to give additional weight to the core arguments of this article.

Results

The landscape of national and per capita level health spending has evolved substantially alongside the past two decades. The average total per capita health spending still remains substantially higher among G7 (4747 $PPP in 2013) compared to the BRICS (1004 $PPP in 2013). The US continue to outweigh joint Total Health Expenditures (THE) of other leading OECD nations with it’s THE rising from $1,008,779 in 1995 (37.70% share of global THE) to $2,872,401 in 2013 (33.26% share of global THE). The G7 share of global health expenditure measured in million current PPP international $US has been falling constantly since 1995 (from 65% in 1995 to 53.2% in 2013), while in BRICS nations it grew from 10.7% in 1995 to 20.2% in 2013. In 2013, Chinese national level medical spending exceeded significantly that of all G7 members except the US in terms of current $PPP. Extensive details on individual countries data are presented in and comparison between BRICS and G7 geopolitical groupings is provided in . Although India’s portion of national health spending remained at the 4% GDP level during all these years, unseen economic prosperity was reflected in absolute terms per capita and national level spending. Russia, Brazil and India, regardless of diverse pathways, all succeeded to gain heavily in terms of their respective global shares of THE (current $PPP basis). The largest part of ongoing changes is attributable to the Chinese over-achievement in many areas, depicted by 4-fold growth of its’ Global THE share from 2.85% in 1995 to 10.42% in 2013 (see ).

Table 1. BRICS and G7 Total Health Expenditures (THE) stratification (WHO NHA data).

Table 2. Total health expenditure (THE) as joint country group investment in health (BRICS and G7), mean per capita spending per group and respective shares of global THE in 1995 and 2013. Table based on WHO National Health Accounts data (Global Health Expenditure Database) 1995–2013; Top tier Emerging Markets definition adopted based on Goldman-Sachs acronym BRICS.

Discussion

The past two centuries of global economic history have been marked by heavy domination of the industrialized nations of the northern hemisphereCitation10. Increasing global South–South trade and co-operation has its shy roots in Non-Aligned Movement during post-WWII decadesCitation11. After the end of the Cold War era the pace of globalization accelerated, affecting national health policies. Ambitious transitional health reforms took place among the leading developing countries from the late 1980s or early 1990s. Mostly during the past two decades major economic changes happening worldwide distinguished the top tier emerging markets (BRICS) from the majority of low and middle income countriesCitation12. Most BRICS nations prior to 1980s were dominantly agricultural economies with a rather weak industrial base. A significant exception from this rule is Russia, with its strong industrial legacy of the former Soviet Union and dominantly European traditions in healthcare system establishmentCitation13. However, since the recent recognition of BRICS’ global economic reach, healthcare within these large nations became increasingly relevant for clinical professionals and policymakers alikeCitation14.

However, the long-term trend in health spending could not be understood properly without comparing top performers from both ends of the scale: representative high-income OECD economies such as G7Citation15 and the BRICS themselves. All 12 countries, regardless of their previous economic background, invested heavily to raise medical care accessibility and affordability to their populationsCitation16,Citation17. Probably the most significant finding revealed in this research is the fact that percentage point share of global health spending was constantly falling among all G7 countries, mostly in favor of the BRIC nations since 1995. There is one notable exception, South Africa, which, regardless of undisputed 3-fold build-up of its health expenditureCitation18, was not able to retain or expand its global share of THE. A minor portion of this global share of health spending virtually moving from the developed towards emerging markets belongs as well to the second tier—the Next Eleven economies consisting of Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Republic of Korea (South Korea), Turkey and VietnamCitation19. However, the joint contribution of these nations to the global THE is several times below the one of BRICS and, therefore, was avoided in the presented dataCitation20.

BrazilCitation21, Russia and India all exceeded the majority of G7 nations in terms of real GDP growth and consecutive health spending before, during and after the global recessionCitation22. Nevertheless, the evident evolution in the medical spending landscape worldwide is dominantly attributable to ChinaCitation23. Regardless of the difficult obstacles of vast rural population and povertyCitation24, their health reforms among other fruits brought gigantic 4-fold growth in Chinese participation in global THE. Four out of five BRICS all share the challenges of rapid urbanization followed by creation of mega cities and extreme regional gaps in access to medical careCitation25. In the course of the first half of the 21st century, China shall experience accelerated population aging to the scale that it becomes the fastest aging large nation. Similar demographic trends have been present in Brazil since the 1980s and Russia from many decades earlierCitation26. Unlike the others, India, as the still young large nation, is likely to experience a demographic dividend in the expected 150 million labor force expansionCitation27. Expenditure statistics, however, do not tell much about the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of resource allocation within these national health systems. So it is quite realistic to assume a large degree of heterogeneity in individual success rates these countries achieve in expansion of their hospital networks and investments into medical education and build-up of professional human capacitiesCitation28. Some of these inter-country differences among the BRICS are deeply reflected in health inequalities. A typical example is far less affordable medical care in rural compared to urban populations. Another issue is significant gender inequality in terms of access of girls to higher education, which is the common challenge in all four nations, with the significant exception of Russia. The impact of global climate change to the population health and deepening existing gaps are most visible in affected dense inhabited seacoast areas of China, India and BrazilCitation29.

G7 nations continue to bear the lions share of global THE. Its internal spending structure is traditionally heavily dominated by the USCitation30. Socioeconomic inequalities continue to affect accessibility of medical technologies to the ordinary people, even in these richest societies. Nevertheless, the vast majority of their populations are decently covered by medical insurance and do have access to high quality and timely delivered medical care. Decent core health outcomes in these countries tend to converge at high life expectancy, low childhood mortality rates, better maternal health, shortened length of hospital stays, extended cancer survival, etc.Citation31. They show that overall performance of G7 national health systems is still far beyond targeted outcomes in BRICS national health strategies. Significant additional burden on the backs of developing world regions is the fact that the rise of non-communicable ‘prosperity’ diseases historically developed much slower in rich industrialized countries. These are now arriving to the low and middle income nations at a much faster pace, leaving them unprepared for a huge burden of medical services provision for chronical illnessesCitation32. There are significant sources of heterogeneity among the G7 as well, reflecting themselves in health inequalities. Quite unique for its chronical inability to provide universal health coverage in this group of countries is the US. After a long evolution, this is likely to be tackled and smoothed by ongoing ‘Obama Care’ health reformsCitation33. Other G7 nations do have their own major domestic challenges in healthcare provision and fundingCitation34. These are mostly related to accelerated population aging, large immigrant populations such as those residing in Germany, France and the UK, and shaken sustainability of health insurance funds due to global recession-induced constraints.

Study limitations

A two decades (19 years) long observation is mostly considered insufficient to reveal long-term health expenditure trends expanding over a centuryCitation35. Some public registries issued and maintained by WHO have come under heavy criticism by professional audiences since publication of the disputed WHO World Health Report of 2000Citation36. Nevertheless, existing WHO NHA records offer comprehensive insight into comparable data, allowing one to track financial flows across national health systems. It is exactly during this time window that most effective health reforms in leading developing countries took place. Since the late 1990s the rise of emerging markets became obvious worldwide, ultimately affecting the global healthcare market. Other objections to the study quality might refer to the reliability of national referring bodies and internal accounting differences of healthcare costs within nations. OECD and World Bank (WB) data could contribute as complimentary data sources to more thorough analysis. The reason why these valuable registries were not used lies in the fact that BRICS nations are not members of OECD. Thus, most indicators of the OECD health data-set refer to only 34 countries. WB health data, although exceptionally comprehensive, was found to be ‘a little noisy’ for some countries and some chronological periodsCitation37. Therefore, existing WHO registries were probably the most reliable single authoritative sources of internationally comparable data being publicly available and covering all target countries. More ambitious research could include statistical trend analysis, observe broader groups of target economies inclusive of entire OECD and Next Eleven countries, and develop medium-term forecasts of the upcoming changes.

Conclusions

The results have witnessed an ongoing evolution of the global THE landscape. Leadership of traditional, high income economies in medical spending in nominal per capita currency values remains undisputed. Nevertheless, participation of G7 in global THE in terms of purchase power parity appears to steadily decrease in favor of top tier emerging markets followed by a large number of other low and middle income countries. Amongst many vulnerabilities of national health systems in BRICS countries, prevailing positive developments seem to be promising continuance of an ambitious increase in health spendingCitation38. G7 nations will probably retain significantly higher levels of healthcare quality, accessibility and affordability, despite short-term challenges such as the global recession and long-term ones such as population agingCitation39. Nevertheless, best performing emerging markets are gaining victories in their way to achieve universal health insurance coverage for their huge populations. Vast out-of-pocket payments affecting the poor, largely informal ones present substantial weakness, affecting the BRICS in the long runCitation40. Other major changes are accelerated population aging, growing incidence of non-communicable diseases and massive rural–urban migrations moving out of balance current health system capabilities in these countriesCitation41. BRICS governments still have a long way ahead to build up equitable and just health systems, allowing access to essential as well as innovative care, primarily to their fast growing middle class citizensCitation42.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

The underlying studies providing evidence for this contribution where funded out of The Ministry of Education Science and Technological Development of the Republic of Serbia Grant OI 175014. Publication of results was not contingent to Ministry’s censorship or approval.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

None declared. JME peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Acknowledgments

None reported.

References

- Getzen TE, Poullier JP. International health spending forecasts: concepts and evaluation. Soc Sci Med 1992;34:1057-68

- Ogura S, Jakovljevic M. Health financing constrained by population aging - an opportunity to learn from Japanese experience. Ser J Exp Clin Res 2014;15:175-81

- Getzen TE. Aging and health care expenditures: a comment on Zweifel, Felder and Meiers. Health Econ 2001;10:175-7

- Jakovljevic M, Laaser U. Population aging from 1950 to 2010 in seventeen transitional countries in the wider region of South Eastern Europe (Original research). SEEJPH 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: https://doi.org/10.12908/SEEJPH-2014-42

- Jakovljevic M, Milovanovic O. Growing burden of non-communicable diseases in the emerging health markets: the case of BRICS; Research Topic: Health Care Financing and Affordability in the Emerging Global Markets. Front Public Health 2015;3:65. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2015.00065

- Lipinska A, Millard S. Tailwinds and headwinds: how does growth in the BRICs affect inflation in the G7? London: Bank of England Working Paper No. 420. 2011

- O’Neill J. Building better global economic BRICs. Global Economics Paper No: 66. Economics; Research from the Goldman Sachs Financial Workbench. 2001. https://www.gs.com. Accessed 5 July 2015

- WHO Global Expenditure Database. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. Available from: http://apps.who.int/nha/database. Accessed 7 July 2015

- Coudert V, Couharde C. Currency misalignments and exchange rate regimes in emerging and developing Countries*. Rev Int Econ 2009;17:121-36

- Maddison A. A comparison of levels of GDP per capita in developed and developing countries, 1700–1980. J Econ Hist 1983;43:27-41

- Onslow S. The Commonwealth and the Cold War, Neutralism, and Non-Alignment. Int Hist Rev 2015. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2015.1053965

- Dominic W, Purushothaman R. Dreaming with BRICs: The Path to 2050. Global Investment Research, 2003. http://www.goldmansachs.com/our-thinking/archive/brics-dream.html. Accessed 10 July 2015

- Tulchinsky TH, Varavikova EA. Addressing the epidemiologic transition in the former Soviet Union: strategies for health system and public health reform in Russia. Am J Public Health 1996;86:313-20

- Jakovljevic MB. The key role of the leading emerging BRIC markets in the future of global health care. Ser J Exp Clin Res 2014;15:139-43

- Kolluri BR, Panik MJ, Wahab MS. Government expenditure and economic growth: evidence from G7 countries. Appl Econ 2000;32:1059-68

- Hitiris T. Health care expenditure and cost containment in the G7 countries. Discussion papers in Economics. York, England, UK: University of York, 1999

- Rao KD, Petrosyan V, Araujo EC, et al. Progress towards universal health coverage in BRICS: translating economic growth into better health. Bull WHO 2014;92:429-35

- McIntyre D, Bloom G, Doherty J, Brijlal P. Health expenditure and finance in South Africa. Published jointly by the Health Systems Trust and the World Bank, 1995.

- Collective Institutional Authorship. Next-11 Emerging Markets. Dubai, UAE: Private Market Assessment Agency, 2015. Available from: http://next11.se/next-11-emerging-markets/. Accessed 1 July 2015

- Jakovljevic MB. (BRIC’s growing share of global health spending and their diverging pathways. Front Public Health 2015;3:135

- Barros AJ, Bertoldi AD. Out-of-pocket health expenditure in a population covered by the Family Health Program in Brazil. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:758-65

- Schrooten M. Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa: strong economic growth-major challenges. DIW Econ Bull 2011;1:18-22

- Han Q, Chen L, Evans T, et al. China and global health. Lancet 2008;372:1439-41

- Liu GG, Zhao Z, Cai R, et al. Equity in health care access to: assessing the urban health insurance reform in China. Soc Sci Med 2002;55:1779-94

- Ivins C. Inequality matters: BRICS inequalities fact sheet. Oxfam Policy and Practice: Climate Change and Resilience 2013;9:39-50

- Korolenko AV. Современный демографический rризис в России и Вологодской области: cущность, причины и основные черты (The Current Demographic Crisis in Russia and Vologda Region: Essence, Causes and Main Features). Human Sci Res 2015;41:UDK 314.06 (1–12)

- Berman PA. Rethinking health care systems: private health care provision in India. World Dev 1998;26:1463-79

- Marten R, McIntyre D, Travassos C, et al. An assessment of progress towards universal health coverage in Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS). Lancet 2014;384:2164-71

- Courtney I. Inequality matters: BRICS inequalities fact sheet. Oxfam Policy and Practice: Climate Change and Resilience 2013;9.1:39-50

- Getzen TE. Health care is an individual necessity and a national luxury: applying multilevel decision models to the analysis of health care expenditures. J Health Econ 2000;19:259-70

- Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, et al. Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2006;367:1747-57

- Boutayeb A. The double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases in developing countries. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2006;100:191-9

- Obama B. Securing the future of American health care. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1377-81

- Labonte R, Schrecker T. Foreign policy matters: a normative view of the G8 and population health. Bull WHO 2007;85:185-91

- Getzen T. 2014 Getzen Macroeconomic dynamics of health: lags and variability in mortality, employment and spending. In: Culyer AJ, ed. Encyclopedia of Health Economics. San Diego, CA: Elsevier, 2014. p 165-76

- Navarro V. Assessment of the world health report 2000. Lancet 2000;356:1598-601

- Stiglitz JE, Chang HJ. Joseph Stiglitz and the World Bank: the rebel within. London, UK: Anthem Press, 2001

- Bliss KE, ed. Key players in global health: how Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa are influencing the game. Washington DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2010

- Labonte R, Schrecker T. Committed to health for all? How the G7/G8 rate. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1661-76

- Leive A, Xu K. Coping with out-of-pocket health payments: empirical evidence from 15 African countries. Bull WHO 2008;86:849-56C

- Watt NF, Gomez EJ, McKee M. Global health in foreign policy—and foreign policy in health? Evidence from the BRICS. Health Policy Plan 2014;29:763-73

- Das DK. Globalisation and an emerging global middle class. Econ Aff 2009;29:89-92