Abstract

Background

Financial pressures have limited the ability of providers to use medication that may improve clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction. New interventions are often fraught with resistance from individual cost centers. A value realization tool (VRT) is essential for separate cost centers to communicate and comprehend the overall financial and clinical implications of post-surgical pain management medication interventions (PSMI). The goal was to describe development of a VRT.

Methods

An evaluation of common in-patient PSMI approaches, impacts, and costs was performed. A multidisciplinary task force guided development of the VRT to ensure appropriate representation and relevance to clinical practice. The main outcome was an Excel-based tool that communicates the overall cost/benefit of PSMI for the post-operative patient encounter.

Results

The VRT aggregated input data on costs, clinical impact, and nursing burden of PSMI assessment and monitoring into two high-level outcome reports: Overall Cost Impact and Nurse & Patient Impact. Costs included PSMI specific medication, equipment, professional placement, labor, overall/opioid-related adverse events, re-admissions, and length of stay. Nursing impact included level of practice interference, job satisfaction, and patient care metrics. Patient impact included pain scores, opioid use, PACU time, and satisfaction. Reference data was provided for individual institutions that may not collect all variables included in the VRT.

Conclusions

The VRT is a valuable way for administrators to assess PSMI cost/benefits and for individual cost centers to see the overall value of individual interventions. The user-friendly, decision-support tool allows the end-user to use built-in referenced or personalized outcome data, increasing relevance to their institutions. This broad picture could facilitate communication across cost centers and evidence-based decisions for appropriate use and impacts of PSMI.

Introduction

There is increasing emphasis on reducing healthcare utilization and improving quality. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid’s Hospital Readmissions Reductions Program and Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) have pressured providers to reduce post-operative length of stay, adverse events and re-admissions or be financially penalizedCitation1,Citation2. Attention has also been put on patient satisfaction, with the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, publicly reported survey of patients’ perspectives of hospital care that will be linked to provider reimbursementCitation3. Thus, tools to optimize patient satisfaction and quality outcomes are essential.

Pain control is related to patient satisfaction and patient outcomesCitation4,Citation5. Pain control also has great financial implications as opioids, which are the most common medication used for post-surgical pain management medication interventions (PSMI), and are frequently associated with adverse effects such as respiratory depression, nausea and vomiting, pruritus, constipation, and post-operative ileus. These adverse effects may result in longer lengths of stay, increased total costs, and higher re-admission ratesCitation6,Citation7. Further, surveys show post-operative pain is under-appreciated and inadequately treatedCitation8. Using conventional pain management strategies, such as opioids, it has been reported that 39% of patients still had moderate/severe pain after receiving their first dose and 80% of patients experienced adverse effectsCitation8. Thus, a method to improve pain interventions would be valuable.

Determining the cost/benefit of such interventions that may optimize financial, provider, and patient outcomes should involve the entire healthcare team. A common roadblock to approval and use of new interventions is often their additional cost and resource utilization. In many institutions, the pharmacy department reviews new medication interventions. The pharmacy assesses the medication cost and cost-effective alternatives to make their decision about availability on the hospital formulary. Even though some medication interventions provide the opportunity for cost savings in other departments or cost centers, those savings or related benefits are not realized by the pharmacy directly. It is the pharmacy that absorbs the addition medication costs. Therefore, without an open line of communication or a tool to present the cost/benefit of a new intervention to the facility as a whole, it is difficult for the pharmacy to justify what they perceive as their initial increased costs. In reality, the benefit in patient outcomes and total costs may outweigh the medication cost. The hospital administration may not be able to evaluate the overall cost saving measure if the new intervention is blocked from utilization before the overall benefits can be evaluated and realized. This is a flaw in the current system.

The goal of this paper is to describe the development of a Value Realization Tool (VRT) that demonstrates the overall clinical and financial impact of post-surgical PSMI across multiple cost centers of an institution. Creating a tool that provides a unique and comprehensive picture may enable enhanced and informed decision-making by administration as they can better assess the overall value of PSMI for any inpatient surgical patient in the post-operative period. Ultimately this may enable communication of the overall cost-effectiveness of a medication intervention across all cost centers.

Methods

For development, a multidisciplinary team of anesthesia, surgery, health economics, pharmacy, nursing, and healthcare administration professionals from 17 academic medical institutions across the US, as well as consultants and employees of Pacira Pharmaceuticals, was sought out as a consortium for the development. The multidisciplinary team was chosen for their expertise and interest in post-surgical pain management.

The first step in developing the VRT was to perform a literature review to identify the most common PSMI used during in-patient care as well as the current costs and clinical issues relevant to each method. The literature search was performed using PubMed, Google Scholar and proceedings from surgical meetings related to post-surgical pain management. It included peer-reviewed literature as well as white papers and unpublished literature (abstracts, posters, websites). The primary search terms used were post-surgical pain medication, intervention, mode of administration, adverse events, length of stay, cost, outcomes and surgical pain management. Published manuscripts, poster presentations and abstracts that focused on ambulatory, outpatient or office settings and submissions not in English were excluded. The specific results from the literature review are found in the Appendix. The team reviewed the results from the literature review to determine variables of interest for a VRT that would be universally beneficial and relevant to individual institutions.

Based on their collective experience and expertise, the consortium determined the input for the VRT analysis should include: intravenous (IV) opioids via a Patient Controlled Analgesia (PCA) device, continuous nerve block using an elastomeric pump, continuous wound infiltration using an elastomeric pump, continuous epidural using a PCA device and wound infiltration using liposomal bupivacaine. The output/data elements selected to measure and report on the impact of PSMI were: costs (medication, equipment, professional services, opioid-related adverse events (ORAE), adverse events (AE), readmission, length of stay (LOS) and healthcare provider (labor time), clinical impacts to patients (opioid use, pain scores, time to discharge from PACU and satisfaction) and the nursing burden of assessment and monitoring the PSMI. The inputs representing the clinical impact to patients were selected as they are common outcomes reported in the literature. Different elements for the input and outputs were also taken from the body of work in the literature review; including hourly salaries for nurses and pharmacists, etc. were taken from the National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates (http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm). The baseline data elements for pain and patient satisfaction were obtained from publicly available reports on the impact of different PSMI in post-surgical analgesiaCitation9. The nursing burden scores were obtained from surveys presented at national conference proceedingsCitation10,Citation11. Data related to IV PCA opioids were taken from a study conducted by Palmer et al.Citation12. In this study, charge data from the Premier network of hospitals was determined for the two most commonly used IV PCA opioids (morphine and hydromorphone). Since the average number of cartridges used in IV PCA over 48 h were provided and all other charges for additional opioids were captured (e.g., PO, IV/IM push), we were able to provide an over-estimate of opioid related charges through to 48 h. Opioid consumption for elastomeric pumps was based on the literature where the intervention was compared to IV PCACitation13. For those comparisons, we expressed the dose of supplemental opioids as a percentage of the dose we calculated for supplemental opioids from IV PCA. The continuous epidural used in the model’s costs assumed that fentanyl and bupivacaine were used. This assumption was validated by consortium members and hospital pain pharmacists.

Once the inputs and outputs were finalized, the team performed a review to assure all were in agreement and the goals of the proposed tool were being addressed. With the consortium’s agreement ensured, a Microsoft Excel-based (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) model was built. Finally, the multidisciplinary team and members of the Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Health Outcomes and Value Assessment Advisory Board reviewed the draft version of this tool. The steps of development are detailed in .

Results

The VRT developed has individual tabs for each data element: medication costs, equipment costs, professional placement costs, opioid related adverse events, adverse events, re-admissions, length of stay, healthcare provider time, nursing impact, and patient impact and satisfaction. Each tab contains input fields for all five PSMI. The end user can use the baseline values provided via the literature review or input their own data to calculate a personalized report of their individual institution’s cost per case by PSMI, cost of all procedures by PSMI, and the total cost across all PSMI to the facility. The baseline value cells are locked to maintain the integrity of the model and citations for the data are provided. The sources for the baseline data are seen in the Appendix.

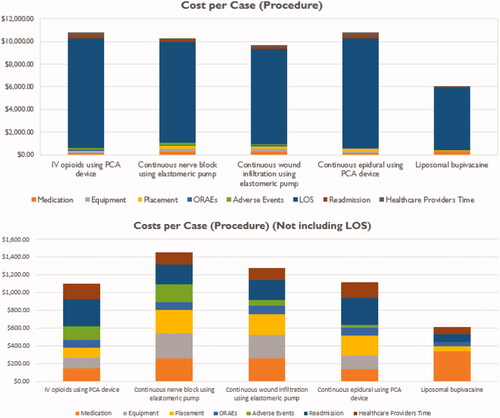

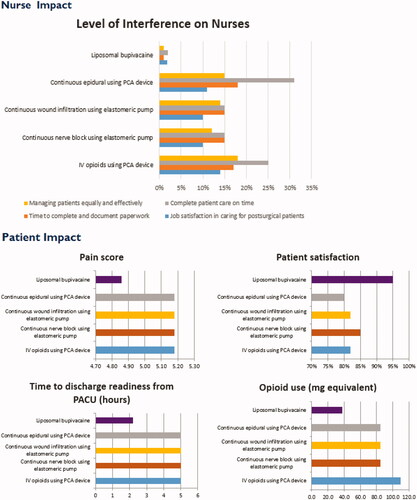

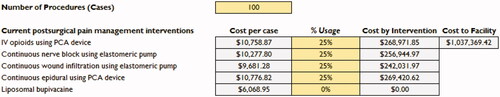

Data from each individual tab is aggregated into two high-level outcome reports: Overall Cost Impact and Nurse and Patient Impact. Overall Cost Impact considers medication, equipment, professional placement, labor, overall/opioid-related adverse events, re-admissions, and length of stay. It calculates cost per procedure, but the user can also input the total number of procedures and the percentage of each PSMI used for the cost of procedures by PSMI and total facility costs. The second report includes Nursing Impact, detailing level of practice interference, job satisfaction, patient care metrics by PSMI and Patient Impact, which includes pain scores, opioid use, Post Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) time, and satisfaction. The back-end algorithms sum the individual input costs and impacts, and then display the results in tabular and graph forms by intervention.

After development, the VRT had rigorous testing of the user interface, benchmark links, and back loaded calculations to ensure the tool met technical expectations. The VRT model produced had 13 tabs. It starts with an introduction reminding the user that the purpose of the Tool is to quantify and report the clinical, economic and provider impact of five PSMI in the inpatient setting (). Each variable or outcome has a corresponding Excel sheet or Tab in the Tool and the data provided for each intervention is specific to that particular intervention. For example, morphine is an option listed for IV opioids using a PCA device, while bupivacaine is an option listed for continuous nerve block. presents the list of categories of the VRT as well as their data sources.

Table 1. VRT data elements and sources.

After the introduction, the next two tabs provide an overarching evaluation of the Overall Cost Impact () and Nurse & Patient Impact (). The Overall Cost Impact is presented in two ways: with and without length of stay (LOS). As demonstrated in , LOS makes up a majority of the cost and could overshadow the impact of the other data elements; therefore, it was decided to present the cost per case without LOS included as well, making it easier for the end user to compare the other costs of the data inputs per case. In addition to the figures, a table representing the cost per case by PSMI is included on the Overall Cost Impact tab ().

Table 2. Cost per case by intervention (values in USD).

Functionality

The calculations are made by category within the individual tabs and then linked to the Overall Cost Impact tab. Each calculation is specific to the specified category. For example, under medication costs, the cost, number of units, and percentage use are all used to calculate the medication costs for each PSMI. When it comes to calculating the costs of ORAE and AE, the cost of an episode of the specified adverse event is multiplied by the percentage incidence of each AE for the specified PSMI and the sum for all of the AE under the PSMI is reported.

AE: Sum (Baseline costs for AE × % Incidence) = Cost per PSMI

HCP Time: Sum (Time spent on task × Wage per Hour) = Cost per PSMI

Another feature of the VRT is the ability to calculate the cost to the facility for a specified number of procedures, taking the percentage use of PSMI among the procedures into account. As presented in , baseline values of total number of procedures and percentage use of each PSMI are provided for the cost calculation. However, as with all other inputs in the VRT, the end user can over-ride the baseline value provided and put in the number of procedures from their institution as well as their percentage usage of PSMI for those procedures. This is important because the number of procedures and percentage use of PSMI varies from site to site, and the VRT is flexible and allows for customization to meet the institution’s specific needs.

Discussion

Post-operative abdominal pain management is a major issue facing patients, medical and nursing staff in daily clinical practice. Effective pain control is essential, as it reduces post-operative morbidity, facilitates rehabilitation, and accelerates recovery from surgeryCitation14. Pain management is directly related to clinical, financial, and patient satisfaction outcomes, thus the implications of poor pain control are exceedingly important in the current healthcare environmentCitation4,Citation9,Citation15. Despite an increased focus on pain control, recent studies show pain continues to be poorly addressed after surgeryCitation8. Flaws in the current system of communicating the value of medication interventions across cost centers have also been identified. Our goal was to develop and describe a Value Realization Tool that communicates the overall clinical and financial impact of post-surgical pain management medication interventions (PSMI) across multiple areas involved in the patient experience. With the development of the VRT, we offer a tool that provides a comprehensive picture of the overall costs of post-surgical pain management that can be used by hospital administrators to assess the value using a specific intervention across cost centers. The tool can also be used by individual cost centers to see the overall costs and benefits across the patient encounter with specific PSMI.

The current model is not focused on specific surgical procedures or approaches, but rather the choice of PSMI. While an institution could potentially use this tool to examine laparoscopic vs open procedures separately and compare outcome parameters, the VRT provides a broad view across multiple cost centers to allow for an assessment of the true value a drug intervention provides to the entire hospital–patient encounter, distinguishing it from other pharmacoeconomic models. There have been previous attempts to construct cost models economical calculators. Models evaluating pharmacoeconomics, such as decision trees, Markov models, and discrete event simulation, have been developed and used for health technology assessment, but these techniques lack the breadth and flexibility required to appropriately represent the full clinical picture and pertinent quality measureCitation16–23. These models are often based on hypothetical cohorts and costs from large-scale administrative databases such as Premier, MarketScan, CMS, or companies such as Humana or Healthcore. Estimations are based on complicated algorithms, pooled data, and outdated cost information. These tools are also not user-friendly, require advanced analytic support staff, and do not allow personalization of data or customization met specific needs. Another limitation of these models is that they do not account for the wide variations in costs across institutions and, therefore, limit the applicability of individualized cost assessments. Further, no model has been developed with the ability to consider the entire multi-dimensional healthcare team into the decision analysis. This is particularly important to pain management as the cost and resource allocations necessary to address a patient’s pain needs spans numerous healthcare providers, such as surgeons, pain teams, anesthesiologists, nurses, and pharmacy. Most models only compare one dimension, often limited to medication differences, and do not consider administrative methods or a variety of interventions, where the additional role of nursing, personnel, and equipment costs come into play. With these necessary capabilities, the VRT can be used to facilitate informed decision-making.

With the Patient and Nursing Impact reports, in addition to the Overall Cost Impact report and detailed costs in each cost center, the VRT can serve as a valuable tool for the hospital administration to support their decision-making. The tool is responsive to the stakeholders, with the ability to personalize input for the exact institutional costs for labor, equipment, and medication used for each specific PSMI, as well as personalization to include the specific medications used in each individual institution’s Enhanced Recovery pathway, if applicable. The adverse events are also customizable and able to be linked to costs per case to demonstrate their actual impact. The institution specific pain scores, discharge readiness, and opioid use are important quality measures for benchmarking and process improvement across the institution. As patient outcomes and satisfaction are being linked to reimbursements, the information calculated by the VRT will be increasingly important. Furthermore, the tool is not specific to any type of surgery, and could be used to examine the impact of PSMI on any surgical procedure, as is commonly performed in drug use evaluations, continuous quality improvement projects, and other assessments related to PSMI.

The VRT also facilitates communication across all cost centers for evidence-based decisions on PSMI, which can lead to better patient centered solutions and improved patient outcomes. One example of the effectiveness of the VRT is post-operative ileus (POI) management. Opioid pain medication is commonly used for post-surgical pain management. However, opioids are associated with a variety of perioperative complications, including sedation, post-operative nausea and vomiting, urinary retention, and respiratory depression, and have negative effects on gastrointestinal functions, including the inhibition of colonic transit, contributing to ileus and constipationCitation24,Citation25. POI is further exacerbated by opioid use in the post-operative periodCitation7. POI is the single largest factor influencing length of stay after colorectal surgery, and has great implications for patient outcomes and healthcare utilizationCitation26,Citation27. Thus, there is a need for alternative post-surgical pain management medication interventions (PSMI) that do not contribute to ileus. Non-opioid analgesics are increasingly being used before, during, and after surgery to facilitate the recovery processCitation28. Studies evaluating approaches to facilitating the recovery process have demonstrated that the use of multimodal analgesic techniques can improve early recovery as well as other clinically meaningful outcomesCitation25,Citation29–32. Thus, the overall cost-effectiveness of these PSMIs should be assessed. However, when comparing multimodal analgesic techniques such as opioid vs non-opioid PSMI, more than the medication costs need to be considered for a complete value picture. The VRT can input the institutional costs for opioid-related adverse event, with ileus specifically. Then, by PSMI, the percentage incidence, impact on LOS, and total cost from POI can be determined. This powerful tool could then help guide decision-making on medication use to reduce adverse effects, additional LOS, and their associated costs.

We recognize the limitations in this undertaking. First, this project describes the development of the tool, and validation using institutional data is still underway. In addition, because specific patient satisfaction measures in the post-operative time frame are under development, we relied on patient satisfaction scores reported at discharge; there measures are subjective and not standardized, and demonstrate areas of future work for the VRT for incorporation of widely-utilized HCAHPS. The model also only considered opioids and did not attempt to include non-opioid analgesics (e.g., NSAIDs, Tylenol, etc.). That could be a direction for future work.

In conclusion, post-operative pain management interventions impact many groups, including the patient care team, the patient, and multiple hospital cost centers. However, with the current evaluation system, interventions may be reviewed and blocked by the pharmacy cost center, as it would have to absorb the higher costs without realizing any of the clinical or overall cost benefits, which are distributed across other cost centers. Therefore, a tool that enables a view across all cost centers for informed decision-making on pain management use is needed. The VRT is a novel, valuable tool that provides this perspective for inpatient surgical patients using pain medication in the post-operative period. The VRT demonstrates the impact and true value of PSMI beyond just the cost of the medication used; it demonstrates the actual costs and impact of the patient’s post-surgical stay across all cost centers at the specific institution, including re-admissions, provider time, and patient satisfaction. With this customizable, broad perspective, the VRT can also support communication across individual cost centers to make evidence-based decisions for appropriate use and impacts of PSMI. Given the value of the tool, further study is warranted to validate the VRT at individual institutions and develop strategies for widespread availability.

Transparency

Declaration of funding

This work was completed with educational grant support from Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Declaration of financial/other relationships

AS is a consultant for Pacira Pharmaceuticals in healthcare outcomes and value. EMH is on the speaker’s bureau for Pacira Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Value_Realization_Tool_v4_0_results.xlsx

Download MS Excel (329 KB)References

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Physician Quality Reporting System. <http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/index.html?redirect=/PQRS/>. Accessed December 2014

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Readmissions Reduction Program. 2012. http://cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html/>. Accessed March 2015

- Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. http://www.hcahpsonline.org. Accessed February 12, 2015

- Joshi GP, Beck DE, Emerson RH, et al. Defining new directions for more effective management of surgical pain in the United States: highlights of the inaugural Surgical Pain Congress. Am Surg 2014;80:219-28

- Iannuzzi JC, Kahn SA, Zhang L, et al. Getting satisfaction: drivers of surgical Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health care Providers and Systems survey scores. J Surg Res 2015;197:155-61

- Gan TJ, Robinson SB, Oderda GM, et al. Impact of postsurgical opioid use and ileus on economic outcomes in gastrointestinal surgeries. Curr Med Res Opin 2015;31:677-86

- Kurz A, Sessler DI. Opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: pathophysiology and potential new therapies. Drugs 2003;63:649-71

- Gan TJ, Habib AS, Miller TE, et al. Incidence, patient satisfaction, and perceptions of post-surgical pain: results from a US national survey. Curr Med Res Opin 2014;30:149-60

- Joshi GP. Postoperative pain management. Int Anesthesiol Clin 1994;32:113-26

- Smalarz A, Razzano L, Gordon D. Impact of postsurgical pain management medication interventions on PeriAnesthetic nurses’ time and workflow. 34th ASPAN National Conference, San Antonio, TX, April 2015

- Smalarz A, Razzano L, Gordon D. Nurses’ awareness related to postsurgical pain, opioids, and opioid-related adverse events. AORN’s Surgical Conference and Expo, 2015, Denver, CO, March 2015

- Palmer P, Ji X, Stephens JM. Cost of opioid intravenous patient-controlled analgesia: results from a hospital database analysis and literature assessment. ClinicoEcon Outcomes Res 2014;6:311-18

- Cottam DR, Fisher B, Atkinson J, et al. A randomized trial of bupivicaine pain pumps to eliminate the need for patient controlled analgesia pumps in primary laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2007;17:595-600

- Al Samaraee A, Rhind G, Saleh U, et al. Factors contributing to poor post-operative abdominal pain management in adult patients: a review. Surgeon 2010;8:151-8

- Gosh S. Patient satisfaction and postoperative demands on hospital and community services after day surgery. Br J Surg 1994;81:1635-8

- Caro JJ. Pharmacoeconomic analyses using discrete event simulation. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23:323-32

- Pradelli L, Povero M, Muscaritoli M, et al. Updated cost-effectiveness analysis of supplemental glutamine for parenteral nutrition of intensive-care patients. Eur J Clin Nutr 2015;69:546-51

- Wielage RC, Myers JA, Klein RW, et al. Cost-effectiveness analyses of osteoarthritis oral therapies: a systematic review. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2013;11:593-618

- Freund DA, Dittus RS. Principles of pharmacoeconomic analysis of drug therapy. Pharmacoeconomics 1992;1:20-31

- Weinstein MC, O'Brien B, Hornberger J, et al. Principles of good practice for decision analytic modeling in health-care evaluation: report of the ISPOR Task Force on Good Research Practices–Modeling Studies. Value Health 2003;6:9-17

- Buti M, Casado MA, Fosbrook L, et al. Financial impact of two different ways of evaluating early virological response to peginterferon-alpha-2b plus ribavirin therapy in treatment-naive patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23:1043-55

- Cavanaugh TM, Martin JE. Update on pharmacoeconomics in transplantation. Prog Transplant 2007;17:103-19; quiz 120

- Briggs A, Sculpher M. An introduction to Markov modelling for economic evaluation. Pharmacoeconomics 1998;13:397-409

- Camilleri M. Opioid-induced constipation: challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:835-42; quiz 843

- White PF. The changing role of non-opioid analgesic techniques in the management of postoperative pain. Anesth Analg 2005;101:S5-22

- Augestad KM, Delaney CP. Postoperative ileus: impact of pharmacological treatment, laparoscopic surgery and enhanced recovery pathways. World J Gastroenterol 2010;16:2067-74

- Viscusi ER, Goldstein S, Witkowski T, et al. Alvimopan, a peripherally acting mu-opioid receptor antagonist, compared with placebo in postoperative ileus after major abdominal surgery: results of a randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Surg Endosc 2006;20:64-70

- Elvir-Lazo OL, White PF. Postoperative pain management after ambulatory surgery: role of multimodal analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin 2010;28:217-24

- Keller DS, Stulberg JJ, Lawrence JK, et al. Process control to measure process improvement in colorectal surgery: modifications to an established enhanced recovery pathway. Dis Colon Rectum 2014;57:194-200

- Wang S, Shah N, Philip J, et al. Role of alvimopan (entereg) in gastrointestinal recovery and hospital length of stay after bowel resection. P T 2012;37:518-25

- Watcha MF, Issioui T, Klein KW, et al. Costs and effectiveness of rofecoxib, celecoxib, and acetaminophen for preventing pain after ambulatory otolaryngologic surgery. Anesth Analg 2003;96:987-94, table of contents

- White PF, Kehlet H, Neal JM, et al. The role of the anesthesiologist in fast-track surgery: from multimodal analgesia to perioperative medical care. Anesth Analg 2007;104:1380-96, table of contents

Appendix

Literature review

1. Asche C, Kirkness C, Ren J, et al. Evaluating clinical and economic outcomes associated with liposomal bupivacaine (LB) for postsurgical pain following total knee arthroplasty (TKA), International Society For Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Annual International Meeting, Philadelphia, PA; 2015

2. Barrington JW. Emerging data in the use of liposome bupivacaine: comparative review in 2,000 TJA patients, in ICJR Symposium at AAOS - Recent advances on incorporation of local analgesics in post surgical pain pathways. 2014: New Orleans, LA

3. Cien AJ, Penny PC, Horn BJ, et al. A retrospective evaluation of surgical site infiltration of liposomal bupivacaine (Exparel) versus femoral nerve blocks with patient-controlled analgesia in patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty, in Mid-America Orthopaedic Association (MAOA) Thirty-Second Annual Meeting. San Antonio, TX; 2014

4. Cohen S, Vogel JD, Marcet JE, et al. Liposome bupivacaine for improvement in economic outcomes and opioid burden in GI surgery: IMPROVE Study pooled analysis. J Pain Res 2014;7:359-66

5. Coley KC, Williams BA, DaPos SV, et al. Retrospective evaluation of unanticipated admissions and readmissions after same day surgery and associated costs. J Clin Anesth 2002;14:349–53

6. Cottam DR, Fisher B, Atkinson J, et al. A randomized trial of bupivicaine pain pumps to eliminate the need for patient controlled analgesia pumps in primary laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2007;17:595–600

7. Cuvillon P, Ripart J, Lalourcey L, et al. The continuous femoral nerve block catheter for postoperative analgesia: bacterial colonization, infectious rate and adverse effects. Anesth Analg 2001;93:1045–9

8. deSouza AL, Park JJ, Zimmern A, et al. Postoperative recovery following laparoscopic colorectal surgery: epidural Vs patient controlled analgesia. Park Ridge, IL: Advocate Research Forum, 2010

9. Emerson RH, Barrington JW, Olugbode MS. Comparison of a continuous femoral nerve block to long-acting bupivacaine wound infiltration as part of a multi-model pain program in total knee replacement, in American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS). New Orleans, LA; 2014

10. Frost & Sullivan. New opportunities for hospitals to improve economic efficiency and patient outcomes: the case of EXPARELTM, a long-acting, non-opioid local analgesic. Mountain View, CA; 2012

11. Hawkins RJ. EXPAREL care pathway drug utilization evaluation in orthopedic surgery. Chicago, IL: Pacira Symposium; 2013

12. Imbelloni LE, Gouveia MA, Cordeiro JA. Continuous spinal anesthesia versus combined spinal epidural block for major orthopedic surgery: prospective randomized study. Sao Paulo Med J 2009;127:7–11

13. Jayr C, Beaussier M, Gustafsson U, et al. Continuous epidural infusion of ropivacaine for postoperative analgesia after major abdominal surgery: comparative study with i.v. PCA morphine. Br J Anaesth 1998;81:887–92

14. Kessler ER, Shah M, Gruschkus SK, et al. Cost and quality implications of opioid-based postsurgical pain control using administrative claims data from a large health system: opioid-related adverse events and their impact on clinical and economic outcomes. Pharmacotherapy 2013;33:383–91

15. Kirkness CS, Ren J, Rainville EC, et al. Pain with rest and activity plays little role in patients discharged early after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). American Pain Society (APS) Annual Scientific Meeting, Palm Springs, CA; 2015

16. Ladak SSJ, Katznelson R, Muscat M, et al. Incidence of urinary retention in patients with thoracic patient-controlled epidural analgesia (TPCEA) undergoing thoracotomy. Pain Manag Nurs 2009;10:94–8

17. Marhofer D, Marhofer P, Triffterer L, et al. Dislocation rates of perineural catheters: a volunteer study. Br J Anaesth 2013;111:800–6

18. Maurer K, Bonvini JM, Ekatodramis G, et al. Continuous spinal anesthesia/analgesia vs. single-shot spinal anesthesia with patient-controlled analgesia for elective hip arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2003;47:878–83

19. Mordin M, Anastassopoulos K, van Breda A, et al. Clinical staff resource use with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia in acute postoperative pain management: results from a multicenter, prospective, observational study. J Perianesth Nurs 2007;22:243–55

20. Moses H, Matheson DHM, Dorsey ER, et al. The anatomy of health care in the United States. JAMA 2013;310:1947–63

21. National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates (May 2013), United States. Bureau of Labor Statistics, United States Department of Labor. http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_nat.htm. Accessed 12/1/14

22. Oderda GM, Evans RS, Lloyd J, et al. Cost of opioid-related adverse drug events in surgical patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2003;25:276–83

23. Palmer P, Ji X, Stephens JM. Cost of opioid intravenous patient-controlled analgesia: results from a hospital database analysis and literature assessment. ClinicoEconomics Outcomes Res 2014;6:311–18

24. Peng L, Ren L, Qin P, et al. Continuous femoral nerve block versus intravenous patient controlled analgesia for knee mobility and long-term pain in patients receiving total knee replacement: a randomized controlled trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014; 2014:569107

25. Singelyn FJ, Ferrant T, Malisse MF, et al. Effects of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine, continuous epidural analgesia, and continuous femoral nerve sheath block on rehabilitation after unilateral total-hip arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2005;30:452–7

26. Tilleul P, Aissou M, Bocquet F, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis comparing epidural, patient-controlled intravenous morphine, and continuous wound infiltration for postoperative pain management after open abdominal surgery. Br J Anaesth 2012;108:998–1005

27. Strategic Market Insight. Findings from surveys conducted in 2014. Unpublished

28. Wheatley RG, Schug SA, Watson D. Safety and efficacy of postoperative epidural analgesia. Br J Anaesth 2001;87:47–61

29. Wong CA, Recktenwald AJ, Jones ML, et al. The cost of serious fall-related injuries at three Midwestern hospitals. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2011;37:81–7