Abstract

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a clinical syndrome whose hallmarks are excessive, anxiety-evoking thoughts and compulsive behaviors that are generally recognized as unreasonable, but which cause significant distress and impairment. When these are the exclusive symptoms, they constitute uncomplicated OCD. OCD may also occur in the context of other neuropsychiatric disorders, most commonly other anxiety and mood disorders. The question remains as to whether these combinations of disorders should be regarded as independent, cooccurring disorders or as different manifestations of an incompletely understood constellation of OCD spectrum disorders with a common etiology. Additional considerations are given here to two potential etiology-based subgroups: (i) an environmentally based group in which OCD occurs following apparent causal events such as streptococcal infections, brain injury, or atypical neuroleptic treatment; and (ii) a genomically based group in which OCD is related to chromosomal anomalies or specific genes. Considering the status of current research, the concept of OCD and OCD-related spectrum conditions seems fluid in 2010, and in need of ongoing reappraisal.

El trastorno obsesivo-compulsivo (TOC) es un síndrome clínico cuyo sello distintivo son los pensamientos desmedidos que provocan ansiedad y conductas compulsivas, los cuales habitualmente no son reconocidos como razonables, pero que causan un distrés y un deterioro significativos. Cuando éstos son los síntomas exclusivos, constituyen un TOC no complicado. El TOC también puede presentarse en el contexto de otras patologías neuropsiquiátricas, principalmente en otros trastornos ansiosos y del ánimo. La pregunta que persiste es si acaso estas combinaciones de trastornos deben considerarse como cuadros independientes, trastornos que co-ocurren o como manifestaciones diferentes de una constelación parcialmente comprendida de los trastornos del espectro del TOC con una etiología común. También se entregan consideraciones adicionales para dos subgrupos según sus potenciales bases etiológicas: 1) un grupo de base ambiental en el cual el TOC ocurre a continuatión de acontecimientos aparentemente causales como las infecciones por estreptococo, el daño cerebral o el tratamiento con neurolépticos atípicos y 2) un grupo de base genómica en que el TOC se relaciona con anomalías cromosómicas o de genes específicos. Considerando el estado actual de la investigatión, parece fácil de manejar el concepto de TOC y de las condiciones del espectro relacionado con el TOC en 2010, pero requiere de una r e evaluatión permanente.

Le trouble obsessionnel-compulsif (TOC) est un syndrome clinique caractérisé par des comportements compulsifs et des pensées excessives à type d'anxiété, généralement reconnus comme déraisonnables, causant une souffrance et un handicap significatifs. Quand ces symptômes sont les seuls, on parle de TOC non compliqué. Mais le TOC peut également survenir dans le contexte d'autres troubles neuropsychiatriques, plus couramment dans le cadre d'autres troubles anxieux ou de troubles de l'humeur. Il reste à savoir si ces troubles doivent être considérés comme indépendants, simultanés ou comme des manifestations différentes d'une constellation incomplètement comprise de troubles du spectre du TOC avec une étiologie commune. Cet article propose des réflexions supplémentaires sur deux sous-groupes éventuels d'origine étiologique: 1) un groupe d'origine environnementale dans lequel le TOC survient après des événements apparemment causaux comme une infection streptococcique, une lésion cérébrale ou un traitement neuroleptique atypique; et 2) un groupe d'origine génomique dans lequel le TOC est lié à des anomalies chromosomiques ou à des gènes spécifiques. Au stade actuel de la recherche, le concept de TOC et de trouble du spectre obsessionnel compulsif semble flou en 2010 et nécessite une réévaluation.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) occurs worldwide, with common features across diverse ethnic groups and cultures. It affects approximately 2% of the population and is associated with substantial social, personal, and work impairment.Citation1,Citation2 In fact, the World Health Organization identified OCD among the top 20 causes of years of life lived with disability for 15- to 44-year-olds.Citation3 Although generally longitudinally stable, OCD is known for its substantial heterogeneity, as symptom presentations and comorbidity patterns can vary markedly in different individuals. Moreover, a number of other psychiatric and neurologic disorders have similar phenomenological features, can be comorbid with OCD, or are sometimes even conceptualized as uncommon presentations of OCD. These include the obsessive preoccupations and repetitive behaviors found in body dysmorphic disorder, hypochondriasis, Tourette syndrome, Parkinson's disease, catatonia, autism, and in some individuals with eating disorders (eg, anorexia nervosa).Citation4-Citation10 These heterogeneous facets of the disorder have led to a search for OCD subtypes that might be associated with different etiologies or treatment responses.

Ruminative, obsessional, preoccupying mental agonies coupled with perseverative, ritualized compulsionresembling behaviors have been depicted in biblical documents as well as Greek and Shakespearian tragedies. In modern nosology, a number of different approaches have been suggested to characterize this syndrome, yet the question of how best to categorize OCD subgroups remains under debate in 2010.

Currently, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) of the American Psychiatric Association, classifies OCD as an anxiety disorder. There have, however, been questions raised about this categorization on the basis of some phenomenological differences between OCD and the other anxiety disorders. As such, suggestions have been made that, in the forthcoming 2012 DSM-5, OCD should be removed from its position as one of the six anxiety disorders - a reformulation still under debate. One solution under discussion is that OCD should constitute an independent entity in DSM-5 (ie, remain outside of any larger grouping), congruent with its designation as such in the current international diagnostic manual, ICD-10 (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems).Citation11-Citation14 An alternative suggestion would group OCD and related disorders into a new Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders (OCSD) category. The concept of an OCSD classification was first postulated over a decade ago.Citation15,Citation16 Later, the original OCSD concept was extended with the proposal that OCD and other compulsive disorders may lie along a larger continuum of corelated compulsive-impulsive disorders.Citation15 Disorders hypothesized at the impulsive end of this spectrum continuum include pathologic gambling, nonparaphilic compulsive sexual activity, and others.Citation17,Citation18 A general feature of these proposed impulsive disorders is that, although they have some repetitive elements, they are generally egosyntonic (in contrast to the egodystonic nature of OCD), often with minimal anxiety and behaviors that are not resisted, and that are usually associated with pleasure (not with relief as in OCD). However, the concept of a compulsive-impulsive continuum has not been widely subscribed to in either a recent survey of OCD experts or in recent reviews.Citation19,Citation20 Some of the original proponents of the OCSD groupings and others in the field have softened the stipulations that implied common underlying etiological components of the OCSD, to a more general notion of "obsessive-compulsive-related disorders (OCRD)".Citation12 This debate continues to wax and wane as additional investigations evaluate the underpinnings of a putative OCD spectrum.Citation21,Citation22 This review focuses on newer contributions to the OCD spectrum concept and efforts to subtype OCD. It does not reiterate already well-evaluated aspects of OCD spectrum concepts recently published in expert reviews (eg, refs 12,23-27). Rather, it discusses new data primarily from recent epidemiologic and clinical research, as well as new quantitative psychological, physiological, and genetic studies with the aim of reappraising and developing additional elements related to the OCSDs and OCRDs. Particular points of emphasis are questions regarding (i) what OCD phenotypes might be of value in present and future genetic studies; and (ii) other types of etiological contributions to OCRDs, with, of course, the ultimate aim of better treatments for OCRDs that might be based on more than our current descriptive nosologies. Our immediate hope in this review is to spur additional thoughts as the field moves towards clarifying how OCD-related disorders might arise and manifest at the phenomenological and mechanistic levels.

What is OCD?

DSM-IV/DSM-IV-TR characterizes OCD by the symptoms outlined in Table I. It is listed within the Anxiety Disorder section. The text highlights that if an individual attempts to resist or delay a compulsion, they can experience marked increases in anxiety and distress that are relieved by the rituals.

OCD symptom heterogeneity in individuals

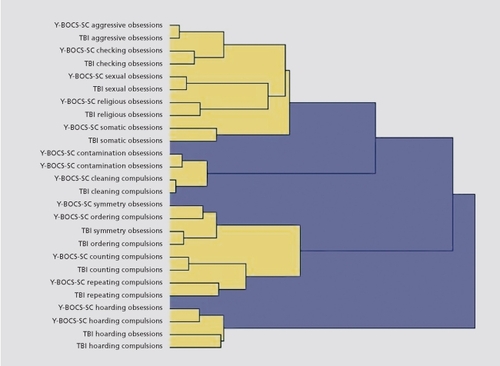

While the core components of OCD (anxiety-evoking obsessions and repetitive compulsions) are recognizable as the cardinal features of OCD, the specific content of these symptoms varies widely. Thus, there is clear evidence that within OCD, there is symptom heterogeneity. For example, depicts the results of a cluster analysis of OCD symptoms based on two separate symptom checklists for OCD (Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Symptom Checklist (YBOCS) and the Thoughts and Behavior Inventory (TBI) accomplished initially using item clusters and subsequently using individual items from these scales, with essentially identical results.Citation29,Citation30 Notable is that there are distinguishable groupings of symptoms, falling into four major groupings (yellow components) and that both obsessions and compulsions of similar types group together. This clustering is in direct contrast to the current DSM-IV notation of obsessions "and/ or" compulsions. There also exists an inseparable overlapping of symptom groupings (blue components), such that despite separable conceptual entities, there is an overall merging of these groupings on a more hierarchical level.

Table I Criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition.

Adapted from ref 28: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. Copyright © American Psychiatric Association 1994

Many other studies over the last decade have attempted to reduce the variability of OC symptom groupings in different populations of OCD patients through factor, cluster, or latent variable analyses of OCD symptom inventories. The majority of such studies have found support for between three to five symptom dimensions,Citation19 with the most commonly identified solution including four factors: (i) contamination obsessions and cleaning compulsions; (ii) aggressive, sexual, religious, and somatic obsessions with checking-related compulsions; (iii) obsessions regarding symmetry, exactness, and the need for things to be "just right" paired with compulsions relating to ordering, arranging, and counting, and (iv) hoarding obsessions and compulsions. With regard to these four symptom dimensions, it should be noted that current debate exists as to whether hoarding should be considered along with the other core OCD symptoms, or whether it exists as an independent syndrome often comorbid with OCD.Citation31-Citation33 We will revisit this issue in a subsequent section of this review. An additional concern that has been raised is that in studies of pediatric OCD, changes in the most prominent symptom patterns have been found over time.Citation34 In contrast, studies of adult OCD populations revealed stability of the most prominent symptom patterns.Citation35,Citation36 This suggests that perhaps more primary symptom dimensions affecting an individual solidify as an individual matures into adulthood. Family studies, including a sib-pair study, indicate that there is statistically significant within-family preferential sharing of symptom types; however, such correlations are relatively modest.Citation37

Given this literature, there does not seem to be an adequate basis for establishing distinct within-OCD subtypes based on OC symptoms that, however, might be useful for distinguishing individuals with OCD for general treatment-directed investigations. There is one important exception with regard to the hoarding subgroup, which has shown several specific genetic-based and brain imaging-based differences from general OCD groups (eg, refs 38-40). Furthermore, given preliminary research that an individual's dominant symptom dimension may in fact be associated with differential treatment response and functional correlates,Citation41,Citation42 future research into hypothesized multidimensional models is warranted.

It is also worth mentioning that a different, two-dimensional model of OCD phenomenology has been suggested since Janet's 1904 reports on 300 patientsCitation43; he highlighted the "anakastic" feature of altered risk assessment (related to the later concepts of harm avoidance or neuroticism) as well as the sense of "indecision" and "incompleteness." Someone suffering from incompleteness was "Continually tormented by an inner sense of imperfection, connected with the perception that actions or intentions have been incompletely achieved."Citation43 This phenomenon has relatively recently been "rediscovered" and seen some empirical study, especially in its narrower sense of the "not just right"Citation44,Citation45 experience frequently seen in OCD.Citation46 Although research tools to characterize patients in this respect remain in development, some promising work has been reported.Citation47,Citation48 Incompleteness symptoms may have more affinity for tic-related phenomena than those strictly encompassed by anxietyrelated mechanisms,Citation49 while Janet's "forced agitations" were also described by him as mental manias.Citation45

Investigators have additionally attempted to subgroup OCD patients using specific phenomenological characteristics, such as overall OCD severity, familiality, gender, age of OCD onset, and comorbidity patterns.Citation24,Citation26,Citation29,Citation50-Citation53 There is considerable indication that OCD which emerges in childhood is meaningfully different from OCD that occurs later in adulthood, including gender and comorbidity differences (eg, a higher prevalence of tic disorders and Tourette syndrome).Citation26,Citation54-Citation56 In addition, some have subgrouped OCD on the basis of the patients' insight into the senselessness of their obsessions and compulsions. Some evidence suggests that OCD patients with poorer insight experience more severe symptoms, are less responsive to treatment, and have more family history of the disorder, though this has not always been observed.Citation57 Interestingly, hoarding symptoms again appear to be distinct from the other OCD symptoms in this regard, in that hoarders typically evidence less insight.Citation53,Citation58,Citation59

In one latent class analysis of comorbid psychiatric conditions, two OCD subgroups were identified: a dimensional anxiety plus depression class and a panic plus tic disorder class.Citation60 Another latent class analysis using a novel latent variable mixture model following a confirmatory factor analysis of 65 OCD-related items in 398 OCD probands found two statistically significant separate OCD subpopulations.Citation30 One group had a significantly higher proportion of OCD-affected relatives (ie, a familial group) and was associated with an earlier age of OCD onset, more severe OCD symptoms, greater psychiatric comorbidity, and more impairment compared with the second group.Citation30 However, because of considerable overlap among groups of OCD symptoms/dimensions and subgroup composition as identified by different statistical methods, discrete subgroup membership for any specific OCD proband is not yet available.Citation30

OCD and its relationship to the anxiety disorders

At the same time as the field attempts to refine and clarify subtypes within OCD, broader questions about the disorder have also been asked, with some proposing that OCD is miscategorized as an anxiety disorder.Citation61 Some have suggested that OCD bears more in common with other disorders categorized by repetitive thoughts and behaviors, and should be moved to a new category of disorders including OCSDs and OCRDs. This proposal requires elucidation of what constitutes the core of OCD: anxiety, obsessions, or repetitive behaviors. It is of note that, under the key features of OCD described in DSM-IV/DSM-IV-TR anxiety, as a feature is mentioned just once.

Nonetheless, many studies of OCD, and particularly investigations of OCD treatment that used quantitative self- and observer ratings, have documented very high anxiety ratings in individuals with untreated OCD. The levels of these anxiety ratings were as high or even higher than those reported in similar studies of panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and specific phobias. Thus, for the present time, OCD's close affinity with other disorders characterized by high anxiety would suggest that it remain under this categorization, unless it becomes recognized as a distinctly separate diagnostic entity in DSM-5, as noted above.Citation14,Citation62,Citation63

OCD and its relationship to mood disorders

Some proponents of moving OCD from its categorization as an anxiety disorder have suggested that, at its core, OCD is an affective disorder. In fact, depressive features are common in OCD and major depressive disorder is the single most frequently comorbid disorder in OCD probands (Table II). Cumulatively, mood disorders occur in 50% to 90% of OCD probands (not taking into account individuals with overlapping mood diagnoses) (Table II) . However, some have found that depressive symptoms most typically emerge following OCD onset, perhaps, it is speculated, as a consequence of long-term anxiety, stresses, and functional impairment associated with OCD symptoms.Citation64 A special comorbid relationship has been noted between OCD and bipolar I and II disorders,Citation1,Citation65,Citation66 also raising the question of a cyclothymic form of OCD.Citation67 As with the affective disorders, modulating factors that seem to affect the expression and some features of OCD include gender and degree of insight into symptoms.Citation53,Citation67,Citation68

It is important to note that, although across OCD groups there exist patterns of frequent comorbidity with other anxiety, mood and other disorders, an "uncomplicated" noncomorbid OCD presentation has nonetheless been documented.Citation69,Citation70 This group, comprising ~10% of OCD probands in several studies, represents a relatively understudied entity,Citation71,Citation72 despite some indications that "uncomplicated" OCD may be of high value in refining the question of "What is OCD?"

OCD: its relationship to OCD-comorbid disorders as part of a description-based OCD spectrum

The original conceptualization of the OCD spectrum: considerations of symptomatology

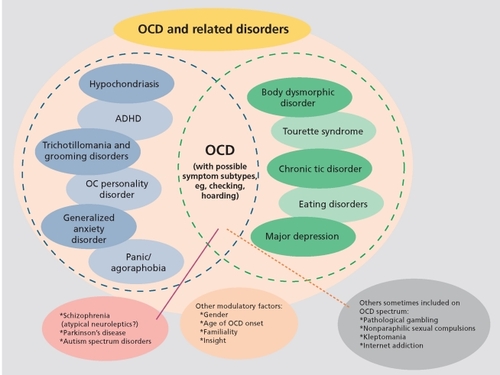

Although there are a number of different approaches and considerations with regard to OCD spectrum disorders, we first present one prevalent view that the spectrum consists of disorders with diverse phenomenological features, but which share commonalities that tie them together. provides a depiction of the original and modified groupings of OCSD and OCRD disorders, including notation of other disorders considered by some as part of a compulsive-impulsive spectrum group of disorders. Some re-evaluations of these relationships have been published recently, Citation12,Citation19,Citation21,Citation27,Citation61,Citation73-Citation75 and reflect the ongoing debate about genetic and environmentallyshaped, neurodevelopmental elements related to OCD onset that also may impact the future status of OCD in DSM-5.

Table II indicates the frequency of comorbid disorders found in adult probands with OCD compared with the incidence of these disorders in the general US population. As is evident, two- to sixfold higher prevalence rates of most psychiatric disorders are found in individuals with OCD. Most striking are the high frequencies of all anxiety disorders taken together, and likewise, all affective disorders. Also of interest are the lack of differences in alcohol-related and substance abuse disorders between those with OCD and the general US population. Specific symptomatologic features that potentially may be useful for grouping OCD into more homogeneous and familial phenotypes for etiologic investigations include those of comorbid tic, affective, anxiety and the other disorders listed, as well as obsessive-compulsive personality disorder.

An example of one OCD-comorbid disorder (not listed in Table I Ibut recently identified as a potential OCRD disorder) is attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).Citation80,Citation81 While some of the original OCD comorbid spectrum disorders remain in this grouping simply on the basis of consistent co-occurrence with OCD in descriptive samplings or overlapping features, others such as ADHD have been validated via segregation analysis. In evaluations of the OCD-ADHD relationship, relatives of probands with both disorders have been found to have a significantly higher frequency of OCD plus ADHD compared with the relatives of probands with ADHD onlyCitation80,Citation81

Table II Disorders occurring together with OCD in five clinical investigationsCitation57,Citation60,Citation71,Citation77,Citation79 and one epidemiologicCitation72 investigation of adult OCD (modified from refs 60,71,77 compared with the incidence of these disorders in the general US populationCitation78). (Percent of total N of individuals with OCD or in the general population)

Apparent environmental etiology-based OCD-related disorders

Three examples of full-blown OCD occurring apparently acutely de novo following putative causal events include: (i) OCD related to an infection such as that associated with streptococcal infections (pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections [PANDAS] syndrome); (ii) trauma-related OCD following acute brain injuries; and (iii) OCD occurrence during treatment of schizophrenia with atypical neuroleptic agents. These would seem to constitute an etiologically-based OCD subtype, since most cases of primary, idiopathic OCD have an insidious onset with a gradual development of symptoms and impairment over a longer timeline of months or years.

OCD and infections: the example of PANDAS syndrome

A potential environmental contributor to the development of OCD, particularly in childhood, is a suspected relationship between group A streptococcal infections and onset of OCD and/or tics/Tourette syndrome, akin to the development of Sydenham's chorea reported previously following streptococcal infection.Citation82-Citation84 In fact, an increased prevalence of obsessive-compulsive symptomsCitation85-Citation87 and OCDCitation88 has also been noted in patients with rheumatic fever (RF) with or without Sydenham's chorea. Initially, these findings were reported in children during an active phase of rheumatic fever.Citation88 Subsequent studies revealed the presence of OCSDs in adults with a previous history of rheumatic fever (not active), suggesting that the streptococcal infection may trigger OCD, which may persist throughout life regardless of the activity of the rheumatic fever.Citation85,Citation86 Recent family studies have reported that OCSDs and OCRDs (such as tic disorders, body dysmorphic disorder, trichotillomania, grooming behaviors, and others) aggregate more frequently in first-degree relatives of rheumatic fever probands when compared with controls.Citation89,Citation90 Moreover, two polymorphisms of the promoter region of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) gene have been associated with both OCD and rheumatic fever, which is an interesting finding since the TNF-α gene is a proinflammatory cytokine involved in rheumatic fever and several other autoimmune diseases,Citation91,Citation92 suggesting that both obsessive-compulsive related disorders and rheumatic fever share a common genetic vulnerability.

Thus, PANDAS OCD could be a mild expression of rheumatic fever whose incidence is higher in developing countries, while the full development of rheumatic feverrelated disorders may be attenuated by the appropriated antibiotic prophylaxis in developed countries. Consistent with this hypothesis, there was a higher family history of rheumatic fever in PANDAS OCD patients. Thus, abnormal immune response to this streptococcal infection, with abnormal antibody production leading to basal ganglia damage has been focused upon as a likely mechanism for both rheumatic fever and PANDAS OCD.Citation52,Citation93,Citation94 This proposed mechanism is supported by behavioral changes and brain lesion development in mice following immunization with streptococcal antigens,Citation95 with resemblances to similar studies investigating immune mechanisms in Sydenham's chorea.Citation83

Abnormal brain autoantibody production may itself be mediated by specific genetic factors, posing a possible gene X environment (G x E) pathogenesis for a PANDAS subgroup. However, a puzzling anomaly potentially reflecting a different possible G x E interaction, or even a confound to the importance of streptococcal infections and autoantibodies in OCD, is that OCD patients with suspected PANDAS had an equal number of OCDaffected relatives as the non-PANDAS comparison OCD population.Citation96 Some recent reviews have concluded that the relationship between strep infections and OCD may be indirect and complex and thus "elusive," Citation97-Citation99 although other controlled studies continue to support an association.Citation100

Besides streptococcal infections and PANDAS, there are interesting examples of other apparent infection-related OCD development. Both bacterial and viral infections have been noted to be associated with acute OCD onset, including Mycoplasma pneumoniae, varicella, toxoplasmosis, Borna disease virus, Behcet's syndrome, and encephalitis, with some infections accompanied by striatal and other brain region lesions.Citation101-Citation106 In some cases, marked OCD symptoms subsided with antibiotic treatment.

Onset of OCD and/or hoarding after acute traumatic brain injury and in association with other types of neuropathology

A number of reports have described new onset of OCD in previously healthy individuals who suffered documented brain injury, usually after accidents (reviews: refs 45,107-109). Besides OCD, other psychiatric disorders that follow brain injuries have been documented in epidemiologic studies.Citation110 In one of these, which retrospectively evaluated 5034 individuals among whom 361 (8.5% weighted average) reported a history of brain trauma with loss of consciousness or confusion, lifetime prevalence was significantly increased (P<0.03-0.0001) for many disorders, including OCD, compared with those without head injuries. An odds ratio of 2.1 was reported for OCD, representing a greater than twofold increase of the occurrence of OCD compared with controls without head injuries, after corrections for age, gender, marital status and socioeconomic status.Citation110 Of note, although similar odds ratios have been found for major depression and panic disorder, rates of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were not increased in this sample of individuals with brain trauma.Citation110

Some case report series noted acute onset of OCD within a day to a few months following traumatic brain injury.Citation107,Citation111,Citation112 One of three studies documented a typical array of OCD symptoms using YBOCS ratings; a subgroup of patients had the generally unusual symptom of "obsessional slowness." Citation107 Compared with matched controls, the patients with post-brain injury OCD symptoms had poorer performance on an array of cognitive measures, including executive functions. Also, the patients with the most severe traumatic brain injury had more frequent abnormal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) exams involving the frontotemporal cortex and the caudate nucleus.Citation107 Some of these reports specifically emphasized the lack of prior personal or familial OCD symptoms or diagnoses.

Smaller survey studies of post-brain injury patients with Ns of 100 or less and using various types of diagnostic evaluations, some quite brief, have infrequently noted cases of OCD, although OCD symptoms have been reported as present in other types of brain disorders, including surgery for seizure disorders and carbon dioxide poisoning, as well as brain tumors and stroke lesions affecting portions of the cortico-striato-pallidothalamic circuits.Citation109,Citation113 OCD and OC symptoms have also been associated with other neurological disorders and neuropathology found in Parkinson's disease, postencephalopathic disorders, and other brain disorders.Citation114,Citation115 Influenced in part by the literature that focal injury to the basal ganglia was associated with OCD emergence, we recently observed an MRI abnormality suggesting elevated iron deposition in the globus pallidus in OCD patients whose symptom onset was from around adolescence to early adulthood.Citation116 This initial result adds to the literature suggesting that age of onset is likely to be an important consideration in attempts to separate OCD into etiologically meaningful subgroups. Age of onset may also be an important variable in regard to the repetitive-compulsive OC traits and OCD itself which are well documented in conjunction with autism spectrum disorders, including Asperger's syndrome.Citation117,Citation118

Apparent acute new onset of OCD in patients with schizophrenia during treatment with atypical antipsychotic medications

One recently-recognized OCD-related disorder is atypical neuroleptic-related OCD, as reported in schizophrenic patients successfully treated with clozapine, ritanserin, and other newer neuroleptic agents.Citation119-Citation122 Some have suggested that this syndrome represents OCD -like symptoms induced by the atypical neuroleptics - ie, a drug side effect. Others subscribe to the hypothesis that suppression of overt and more dominant psychotic symptoms by clozapine and other atypical neuroleptics unveils coexisting OCD, permitting diagnosis. The latter would be in accord with some suggestions from earlier studies that reported as many as 5% to 20%, or more of individuals with schizophrenia have comorbid OCD.Citation123-Citation125 It seems more studies are required to evaluate these two somewhat opposing views of this syndrome.

Of note, other detrimental, traumatic life events of a psychological or social nature have been associated with OCD with different possible implications. For instance, one study compared patients with OCD plus post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who developed OCD after clinically significant trauma (designated "post-traumatic OCD") to general OCD patients in terms of sociodemographic and clinical features. Compared with general OCD patients, "Post-traumatic OCD" presented several phenotypic differences such as: later age at onset of obsessions; increased rates of some obsessive-compulsive dimensions (such as aggressive and symmetry features); increased rates of mood, anxiety, impulse-control and tic disorders; greater "suicidality and severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms; and a more frequent family history of PTSD, major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder." Citation79,Citation126 One study of a treatment-resistant OCD subgroup found that all subjects who met formal criteria for OCD and comorbid PTSD had PTSD onset that preceded OCD onset.Citation127

What is there to make of this diversity of antecedent events suggested to trigger typical OCD? One concept, elaborated below, is that severe acute or more chronic stresses that impact executive (or "ego") functions may elicit a kind of regression to or activation of less goal-oriented but more simplified, ritual-based action patterns that may act to prevent further disorganization of the self.Citation128,Citation129 In this view, OCD "strategies" and symptoms may provide a common pattern of behaviors that are of advantage in the short term, but which may become deleterious if sustained beyond the time of stress.

Putative chromosomal or gene-based, genomic OCD-related disorders

At present, studies of possible genetic contributions to OCD and OCSD remain quite limited. Apart from investigations of specific candidate genes and generelated syndromes, as noted below, the greatest effort in the last decade has been directed towards genome-wide linkage and, more recently, genome-wide association studies that are primarily based upon groups of individuals with DSM-IV-diagnosed OCD without concern for OCD-related subgroups. As reviewed previously and in this same issue, there have been several recent evaluations of genetic contributions to OCD.Citation130-Citation133 In addition, specific investigations of some candidate genes have been subject to meta-analysis with positive results, eg, the SLC6A4 (serotonin transporter gene) polymorphisms,Citation134 plus positive results from investigations of rare variants in SLC6A4 (review in ref 135).

However, in large part these reviews and evaluations of specific genes have not gone beyond generic OCD to address possible associations with OCD spectrum disorders. One notable exception deserves comment. Among five positive studies of variants in SLC1A1 (the neuronal glutamate transporter gene), one study reported separable results for different single-nucleotide polymorphisms associated with overall OCD from associations of a novel 5'-prime region variant (that was not found in the overall OCD sample) with hoarding compulsions.Citation39 This is reminiscent of the report of different patterns of associations with hoarding compulsions compared to associations with overall OCD or with Tourette syndrome for chromosomal regions in genome linkage studies.Citation38,Citation136 In one of these studies, those with OCD plus hoarding exhibited a novel peak on chromosome 14; likewise, in a subgroup of individuals with OCD but from which the individuals with hoarding had been deleted, the peak on chromosome 3q became more distinct.Citation38,Citation137

In keeping with these results, prior studies from different vantage points have suggested that individuals with OCD and hoarding might differ from others with OCD without hoarding, and that hoarding itself might represent a separate syndrome within the OCRDs.Citation31,Citation32 Providing further support for this notion, brain imaging results have indicated that individuals with OCD have distinctly different patterns of cerebral glucose utilization from nonhoarding OCD patients.Citation40 Additionally, hoarding is more frequent in the first-degree relatives of hoarding probands, and hoarding is associated with other biological and gender differences.Citation31,Citation33,Citation37,Citation68,Citation71,Citation138-Citation141

Thus, with only a few interesting exceptions, the chromosomal regions discovered in the genome-wide linkage studies of OCD as possibly harboring OCD-related genes are relevant only to OCD in general, without much attention to OCD diversity and heterogeneity, or with regard to other OCSDs. The same is true for those studies focusing on a single candidate gene. One other exception of possible future interest in regard to likely gene-related subgroupings is age of OCD onset.Citation137

Common gene variants plus rare gene and genetic syndromes associated with OCD and OCD/Tourette syndrome subgroups and/or OCD-related disorders

Uncommon chromosomal anomalies and both rare and common gene variants have come under increasing scrutiny in OCD and OCD-related or OCD-comorbid disorders. Several uncommon chromosomal region abnormalities that are associated with multiple phenotypes have been found to include individuals with OCD. Thus, OCD diagnoses have been made in individuals with the 22q11 microdeletion syndrome (also known as velocardiofacial syndrome).Citation142-Citation145 In one comprehensive study that used the YBOCS scale together with psychiatric interviews in evaluating a VCSF clinic sample, 33% received an OCD diagnosis.Citation142

OCD has also been diagnosed in some individuals with the myoclonus dystonic syndrome related to chromosome 7q.Citation146-Citation149 In one study of three extended myoclonus dystonic syndrome families, OCD meeting direct interview-based DSM-FV criteria was present in 25% (4/16) of symptomatic myoclonus dystonia syndrome carriers with the 7q21 haplotype, but in only 9% (1/11) of nonsymptomatic carriers and 0% (0/28) of the nonhaploytpe carriers.Citation146 This is of special interest because its 7q21-q31 locus is near the chromosomal anomalies described in other individuals with OCD or Tourette syndrome but without the myoclonus dystonic syndrome who have anomalies in chromosome regions 7q31 and 7q35-36.Citation150-Citation152 Additionally, a family-based association study using markers in the 7q31 region demonstrated biased transmission of these marker alleles in individuals with comorbid Tourette syndrome, OCD, and ADHD.Citation153

For the 22q11 and 7q variants, insufficient data exist for OCD, OCD spectrum disorders like other dystonias,Citation154-Citation157 and possibly related disorders like autism spectrum disorder to draw firm conclusions as to how these different disorders might be related. However, these findings from uncommon chromosomal regions and rare genes suggest distinct and different etiologies for an OCD phenotype that may represent a type of OCD spectrum disorder, ie, a genomic group of OCSDs. For example, as noted above, one common candidate gene, SLC1A1, manifested a variant associated with complex hoarding, while different variants were strongly associated with OCD in general.Citation135

Discussion: what might be common elements that could contribute to OCD spectrum disorders?

The relationships among OCD comorbid disorders and additional OCD spectrum disorders: old and new postulated groupings

From an overview perspective, OCD remains as a distinct clinical entity, with classic symptoms and behaviors involving obsessions and compulsions plus high anxiety and, over the lifetime, the occurrence of mood and other anxiety disorders. OCD differs from the other anxiety disorders by its earlier age of onset, more complex comorbidity, and severity of obsessional thoughts and compulsive behaviors. OCD as defined in DSM-IV/IV-TR also occurs concomitantly with other DSM-defined disorders ranging from body dysmorphic disorder, Tourette syndrome, eating disorders, and autism spectrum disorders,Citation118 as well as multiple other disorders. Individuals with these other primary disorders may have separately defined OCD meeting full criteria. There seem to be two views about this overlap: (i) All of these disorders together constitute an OCD spectrum group, with implications that they are all manifestations of a single OC-based entity; or (ii) each may be an independent coexisting disorder. For some individual patients, it may be that a mixture of both may be operative for different components of these disorders. Thus, the relationship among OCD-related disorders remains uncertain.

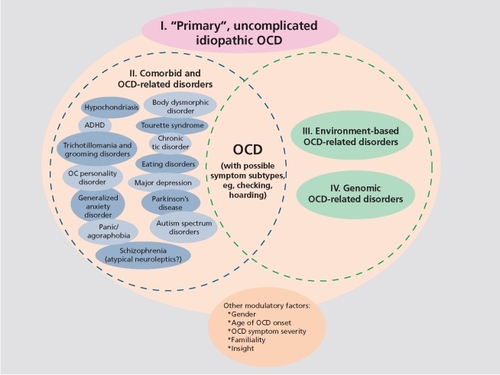

We have noted that a number of other disorders have sometimes been named in an extended list of OCD spectrum disorders () such as the impulsive disorders; however we will not discuss them further, as their association to OCD is tenuous and not acknowledged by most experienced clinicians and researchers or recent reviews.Citation19 On the other hand, we have explicitly added two additional groupings of OCD-related disorders that are not based on descriptive nosology, but rather on etiologic considerations ( ). One of these links acute OCD onset to environmental events such as the consequences of infection, traumatic brain injury, and other neurological disease insults. The other newly suggested OCD spectrum encompasses etiologies related to specific gene or narrow chromosome region-related syndromes - a fourth genomic OCD-related group. Some of this latter group also overlaps with disorders such as Tourette syndrome, with its common tripartite combination of tic disorders, OCD, and ADHD. It is of interest that some considerations for DSM-5 and future DSMs are beginning to show additional elements beyond clinical symptoms as bases for designation of an entity. These include biological, psychophysiological, and brain imaging data as well as potential etiological factors including genetic elements and brain neurocircuitry contributions.Citation6,Citation12,Citation14,Citation19,Citation22,Citation25-Citation26

Evaluations of treatment responses and familiality of treatment responses as possible bases for OCD-related subgroups

Like OCD, many of the OCD-related spectrum disorders respond to serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs), which some have used as evidence for an association between these conditions. However, given that individuals with these disorders often suffer from comorbid disorders that also respond to SRIs (eg, major depressive disorder and other anxiety disorders), as well as the fact that many other neuropsychiatric and medical disorders with no postulated relationship to OCD also respond to SRI treatment, this treatment responsivity seems patently a weak hypothesis. On the other hand, it is notable that many anxiety disorders, but not OCD, benefit from monotherapy with other types of anxiolytic agents such as benzodiazepines.

Psychological treatments with specificity for OCD provide a more discriminating test for grouping disorders together based on treatment response. Exposure and Ritual Prevention (ERP) is one treatment of choice for OCD, and several studies have demonstrated that body dysmorphic disorder and hypochondriasis also respond to psychological treatments incorporating elements of ERP. Worthy of additional study would be comparative examination of whether nonresponse to other antidepressants compared with anxiolytics such as benzodiazepines might characterize subgroups of these other OCD-related disorders. Data from such approaches are sparse, with very few head-to-head studies like those done in OCD of SRIs versus norepinephrine transporter inhibitors such as desipramine or drugs affecting other neurotransmitter systems that have been reported (eg, ref 158).

Likewise, while there is evidence for some features of OCD to exhibit family-based relationships in treatment responses, as recently reviewed,Citation26 similar data are very meager for OCD-related disorders other than major depression. Thus, these notions have not yet been adequately explored across more than a handful of disorders related to OCD to provide an adequate treatmentbased subcategorization of these disorders or to provide a common understanding of them.

Additional approaches to understanding OCSDs and OCRDs: brain imaging studies, putative endophenotypes (including neuropsychological and neurophysiologic measures) and hints from animal models

Brain imaging investigations of OCD patients have only relatively recently been expanded to include some subgroups such as body dysmorphic disorder and compulsive hoarding. Specific investigations have included positron emission tomography (PET) studies of glucose utilization and MRI-based volumetric studies of components of the cortico-striato-pallido-thalamic circuits most implicated in OCD. Another approach has been PET studies using specific ligands and magnetic resonance spectroscopy-based studies of specific brain chemicals to evaluate receptor and transporter elements of neurotransmitter signaling pathways.Citation159,Citation160

Most studies thus far have endeavored to compare OCD patients with controls, or occasionally other neuropsychiatric patient groups, or pre- and post-treatment comparisons. There has been a decided lack of investigations considering the OCD-related disorders. Expense, difficulty, and time limit the numbers of individuals that can be studied, and thus there are only a very few studies of OCD subgroups, such as one comparing OCD patients with and without hoardingCitation40 and studies comparing the symptom dimensions of OCD.Citation161 A similar situation exists for psychological and physiological measures or endophenotypes and for animal models, all of which are at the stage of mostly searching for relevant measures for OCD phenotypes.Citation162-Citation164

One rodent model, which documented changes in microneuroanatomical structures in pathways that were associated with shifts from normal goal-directed behaviors to more limited, habit -based "compulsive" behaviors following multiple types of chronic stressors would seem of relevance to environmental trauma and stress as discussed above regarding the genesis of an environmental OCD spectrum.Citation128 Conceptually, combinations of stresses (from the environment such as psychological traumatic events and from disease-based etiologies such as neurologic disorders or comorbid anxiety, mood, or other neuropsychiatric disorders), plus genetic vulnerabilities might be envisaged as combining to lead towards temporarily adaptive OCD-related thoughts and behaviors that limit further nonadaptive disorganization. Their continuation, however, past the times of most marked stress, may become nonadaptive - a sustained reduction in abilities to act towards more adaptive, social, and occupational goal-directed functions. Prior clinical data and theoretical formulations have led to some similar suggestions resembling this interpretation and application to OCD of this experimental animal model.Citation128

Conclusions

Thus, we are left with a multifaceted array of obsessivecompulsive features that cut across traditional (DSM-IV/TR) as well as draft plans for the DSM-5. Before elaborating what comprises OCSD and OCRD, it seems important to consider "uncomplicated," OCD, as such individuals may be important to study for many purposes and comparisons.Citation69,Citation70 For example, if our current nosologic distinctions retain some validity, detailed knowledge of uncomplicated OCD may help to clarify which genes are more directly OCD-related when coexisting mood, anxiety, and other groupings of comorbid disorders and their underlying genes are also present. However, even uncomplicated OCD demonstrates symptom heterogeneity, leading to continuing efforts such as using latent class modeling to go beyond factor and cluster analyses in order to parse the condition into more valid groups. Considering underlying features, stressors and the other environmental contribution to symptoms may be additional factors to consider in these investigations.

In view of the present diagnostic scheme, there is some consensus that entities such as body dysmorphic disorder, hypochondriasis, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder share the highest apparent phenotypic overlap with OCD. At the same time, the most commonly occurring disorders comorbid with an OCD diagnosis are anxiety and mood disorders, especially major depressive disorder and dysthymia, and even bipolar disorder.Citation165 Another interesting connection with additional disorders arises from segregation, and other analyses that have shown that ADHD and bipolar disorder occur in OCD and the families of OCD probands as frequently as these disorders occur in family studies of each of the primary disorders, ADHD, and bipolar disorder.Citation71,Citation80,Citation81 Thus it is apparent that OCD does co-occur with a wide variety of disorders, and certainly some share enough in common to be considered OCD-related.

The search for OCD subtypes and spectrum conditions over the past 15 years has sought to clarify the constellation of features associated with OCD, but has proved to be a monumental task, sometimes beset by false paths and perhaps spurious associations such as the suggestion of an impulsive-compulsive continuum and a range of problems only very distantly resembling OCD (eg, , lower right). Recently, however, efforts have been made to emphasize shared underlying mechanisms and etiologies. For example we have reviewed two examples of etiologically based OCD presentations that could comprise new OCD-related disorder groupings. Another avenue of approach is the weaving together of model approaches from experimental (eg, brain imaging) and genetic models, combined with more detailed empirical studies of the phenotypical heterogeneity of individuals with OCD and similar disorders.Citation129,Citation164,Citation166,Citation167 With recent advances from ongoing clinical investigations and other research, the state of OCD and OCD-related spectrum disorders is evolving rapidly, with many interesting new developments, as elaborated in a surge of recent publications. It is to be hoped that, together, this work will result in an etiologically based diagnostic scheme that in turn will help advance diagnosis and treatment of these disabling illnesses.

The views expressed in this article are the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NIMH.

Selected abbreviations and acronyms

| ADHD | = | attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder |

| DSM | = | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |

| OCD | = | obsessive-compulsive disorder |

| OCRD | = | obsessive-compulsive-related disorder |

| OCSD | = | obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder |

| PANDAS | = | pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections |

| PTSD | = | post-traumatic stress disorder |

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIMH, NIH. The authors are grateful to Theresa B. DeGuzman for her editorial and artwork assistance.

REFERENCES

- AngstJGammaAEndrassJet al.Obsessive-compulsive severity spectrum in the community: prevalence, comorbidity, and courseEur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci200425415616415205969

- KesslerRCBerglundPDemlerOJinRMerikangasKRWaltersEELifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationArch Gen Psychiatry20056259360215939837

- MurrayCJLopezADEvidence-based health policy--lessons from the Global Burden of Disease StudyScience19962747407438966556

- AltmanSEShankmanSAWhat is the association between obsessivecompulsive disorder and eating disorders?Clin Psychol Rev2009296384619744759

- FallonBAQureshiAILajeGKleinBHypochondriasis and its relationship to obsessive-compulsive disorderPsychiatr Clin North Am20002360561610986730

- FerraoYAMiguelESteinDJTourette's syndrome, trichotillomania, and obsessive-compulsive disorder: how closely are they related?Psychiatry Res2009170324219801170

- FinebergNASharmaPSivakumaranTSahakianBChamberlainSRDoes obsessive-compulsive personality disorder belong within the obsessive-compulsive spectrum?CNS Spectr20071246748217545957

- PhillipsKAPintoAMenardWEisenJLManceboMRasmussenSAObsessive-compulsive disorder versus body dysmorphic disorder: a comparison study of two possibly related disordersDepress Anxiety20072439940917041935

- HermeshHHoffnungRAAizenbergDMolchoAMunitzHCatatonic signs in severe obsessive compulsive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry199051259259

- HuttonJGoodeSMurphyMLe CouteurARutterMNew-onset psychiatric disorders in individuals with autismAutism20081237339018579645

- CastleDJPhillipsKAObsessive-compulsive spectrum of disorders: a defensible construct?Aust N Z J Psychiatry20064011412016476128

- HollanderEKimSBraunASimeonDZoharJCross-cutting issues and future directions for the OCD spectrumPsychiatry Res20091703619811839

- LochnerCSeedatSSteinDJChronic hair-pulling: phenomenologybased subtypesJ Anxiety Disord2009

- StorchEAAbramowitzJGoodmanWKWhere does obsessive-compulsive disorder belong in DSM-V?Depress Anxiety20082533634718412060

- HollanderEWongCMObsessive-compulsive spectrum disordersJ Clin Psychiatry199556 Suppl 436discussion 53557713863

- HollanderEObsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders: an overviewPsychiatric Annals199323355358

- LochnerCHemmingsSMKinnearCJet al.Cluster analysis of obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: clinical and genetic correlatesCompr Psychiatry200546141915714189

- DurdleHGoreyKMStewartSHA meta-analysis examining the relations among pathological gambling, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and obsessive-compulsive traitsPsychol Rep200810348549819102474

- Mataix-ColsDRosario-CamposMCLeckmanJFA multidimensional model of obsessive-compulsive disorderAm J Psychiatry200516222823815677583

- PotenzaMNKoranLMPallantiSThe relationship between impulsecontrol disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a current understanding and future research directionsPsychiatry Res2009170223119811840

- AbramowitzJSTaylorSMcKayDObsessive-compulsive disorderLancet200937449149919665647

- RegierDAObsessive-compulsive behavior spectrum: refining the research agenda for DSM-VPsychiatry Res20091701219811838

- HollanderEKimSKhannaSPallantiSObsessive-compulsive disorder and obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders: diagnostic and dimensional issuesCNS Spectr20071251317277719

- Mataix-ColsDvan den HeuvelOACommon and distinct neural correlates of obsessive-compulsive and related disordersPsychiatr Clin North Am200629391410, viii16650715

- McKayDAbramowitzJSCalamariJEet al.A critical evaluation of obsessive-compulsive disorder subtypes: symptoms versus mechanismsClin Psychol Rev20042428331315245833

- MiguelECLeckmanJFRauchSet al.Obsessive-compulsive disorder phenotypes: implications for genetic studiesMol Psychiatry20051025827515611786

- LeckmanJFBlochMHKingRASymptom dimensions and subtypes of obsessive-compulsive disorder: a developmental perspectiveDialogues Clin Neurosci200911213319432385

- American Psychiatric AssociationDiagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association 1994

- HaslerGLaSalle-RicciVHRonquilloJGet al.Obsessive-compulsive disorder symptom dimensions show specific relationships to psychiatric comorbidityPsychiatry Res200513512113215893825

- SchoolerCRevellAJTimpanoKRWheatonMMurphyDLPredicting genetic loading from symptom patterns in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a latent variable analysisDepress Anxiety20082568068818729144

- AbramowitzJSWheatonMGStorchEAThe status of hoarding as a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorderBehav Res Ther2008461026103318684434

- PertusaAFullanaMASinghSAlonsoPMenchonJMMataix-ColsDCompulsive hoarding: OCD symptom, distinct clinical syndrome, or both?Am J Psychiatry20081651289129818483134

- WuKDWatsonDHoarding and its relation to obsessiveBehav Res Ther20054389792115896286

- RettewDCSwedoSELeonardHLLenaneMCRapoportJLObsessions and compulsions across time in 79 children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry199231105010561429404

- Mataix-ColsDRauchSLBaerLet al.Symptom stability in adult obsessive-compulsive disorder: data from a naturalistic two-year followup studyAm J Psychiatry200215926326811823269

- RuferMGrothusenAMassRPeterHHandITemporal stability of symptom dimensions in adult patients with obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Affect Disord2005889910216040125

- HaslerGPintoAGreenbergBDet al.Familiality of factor analysisderived YBOCS dimensions in OCD-affected sibling pairs from the OCD Collaborative Genetics StudyBiol Psychiatry20076161762517027929

- SamuelsJShugartYYGradosMAet al.Significant linkage to compulsive hoarding on chromosome 14 in families with obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics StudyAm J Psychiatry200716449349917329475

- WendlandJRMoyaPRTimpanoKRet al.A haplotype containing quantitative trait loci for SLC1A1 gene expression and its association with obsessive-compulsive disorderArch Gen Psychiatry20096640841619349310

- SaxenaSBrodyALMaidmentKMet al.Cerebral glucose metabolism in obsessive-compulsive hoardingAm J Psychiatry20041611038104815169692

- Mataix-ColsDRauchSLManzoPAJenikeMABaerLUse of factoranalyzed symptom dimensions to predict outcome with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and placebo in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorderAm J Psychiatry19991561409141610484953

- AlonsoPMenchonJMPifarreJet al.Long-term follow-up and predictors of clinical outcome in obsessive-compulsive patients treated with serotonin reuptake inhibitors and behavioral therapyJ Clin Psychiatry20016253554011488364

- JanetPLes Obsessions et la Psychasthenie 2nd ed. Paris, France: Bailliere 1904

- RasmussenSAEisenJLThe epidemiology and differential diagnosis of obsessive compulsive disorderJ Clin Psychiatry199455 (suppl)510discussion 11147961532

- PitmanRKPierre Janet on obsessive-compulsive disorder (1903). Review and commentaryArch Gen Psychiatry1987442262323827518

- ColesMEHeimbergRGFrostROSteketeeGNot just right experiences and obsessive-compulsive features: experimental and self-monitoring perspectivesBehav Res Ther20054315316715629747

- EckerWGonnerSIncompleteness and harm avoidance in OCD symptom dimensionsBehav Res Ther20084689590418514616

- SummerfeldtLJUnderstanding and treating incompleteness in obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Clin Psychol2004601155116815389620

- MiguelECdo Rosario-CamposMCPradoHSet al.Sensory phenomena in obsessive-compulsive disorder and Tourette's disorderJ Clin Psychiatry20006115015610732667

- GoodmanWKPriceLHRasmussenSADelgadoPLHeningerGRCharneyDSEfficacy of fluvoxamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder. A double-blind comparison with placeboArch Gen Psychiatry19894636442491940

- GoodmanWKPriceLHRasmussenSAHeningerGRCharneyDSFluvoxamine as an antiobsessional agentPsychopharmacol Bull19892531352505302

- SlatteryMJDubbertBKAllenAJLeonardHLSwedoSEGourleyMFPrevalence of obsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with systemic lupus erythematosusJ Clin Psychiatry20046530130615096067

- CatapanoFPerrisFFabrazzoMet al.Obsessive-compulsive disorder with poor insight: A three-year prospective studyProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry20103432333020015461

- EichstedtJAArnoldSLChildhood-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder: a tic-related subtype of OCD?Clin Psychol Rev20012113715711148894

- de MathisMADinizJBShavittRGet al.Early onset obsessive-compulsive disorder with and without ticsCNS Spectr20091436237019773712

- JanowitzDGrabeHJRuhrmannSet al.Early onset of obsessivecompulsive disorder and associated comorbidityDepress Anxiety2009261012101719691024

- CarminCWiegartzPSWuKDObsessive-Compulsive disorder with poor insight. In: Abramowitz JS, McKay D, Taylor S, edsClinical Handbook of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Related Problems Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press 2008109125

- LochnerCKinnearCJHemmingsSMet al.Hoarding in obsessivecompulsive disorder: clinical and genetic correlatesJ Clin Psychiatry2005661155116016187774

- StorchEALackCWMerloLJet al.Clinical features of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder and hoarding symptomsCompr Psychiatry20074831331817560950

- NestadtGDiCZRiddleMAet al.Obsessive-compulsive disorder: subclassification based on co-morbidityPsychol Med2008111

- HollanderEBraunASimeonDShould OCD leave the anxiety disorders in DSM-V? The case for obsessive-compulsive-related disordersDepress Anxiety20082531732918412058

- McKayDNezirogluFMethodological issues in the obsessive-compulsive spectrumPsychiatry Res2009170616519804912

- Mataix-ColsDPertusaALeckmanJFIssues for DSM-V: how should obsessive-compulsive and related disorders be classified?Am J Psychiatry20071641313131417728412

- DemalULenzGMayrhoferAZapotoczkyHGZitterlWObsessivecompulsive disorder and depression. A retrospective study on course and interactionPsychopathology1993261451508234627

- FreemanMPFreemanSAMcElroySLThe comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: prevalence, psychobiology, and treatment issuesJ Affect Disord20026812311869778

- MasiGPerugiGToniCet al.Obsessive-compulsive bipolar comorbidity: focus on children and adolescentsJ Affect Disord20047817518315013241

- HantoucheEGAngstJDemonfauconCPerugiGLancrenonSAkiskalHSCyclothymic OCD: a distinct form?J Affect Disord20037511012781344

- WheatonMTimpanoKRLasalle-RicciVHMurphyDCharacterizing the hoarding phenotype in individuals with OCD: associations with comorbidity, severity and genderJ Anxiety Disord20082224325217339096

- HollanderEGreenwaldSNevilleDJohnsonJHornigCDWeissmanMMUncomplicated and comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder in an epidemiologic sampleDepress Anxiety199641111199166639

- HuppertJDSimpsonHBNissensonKJLiebowitzMRFoaEBQuality of life and functional impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a comparison of patients with and without comorbidity, patients in remission, and healthy controlsDepress Anxiety200926394518800368

- LaSalleVHCromerKRNelsonKNKazubaDJustementLMurphyDLDiagnostic interview assessed neuropsychiatric disorder comorbidity in 334 individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorderDepress Anxiety20041916317315129418

- RuscioAMSteinDJChiuWTKesslerRCThe epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey ReplicationMol Psychiatry201015536318725912

- GellerDAObsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders in children and adolescentsPsychiatr Clin North Am200629353357016650713

- FornaroMGabrielliFAlbanoCet al.Obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders: a comprehensive surveyAnn Gen Psychiatry20098131319450269

- HantoucheEGLancrenonS[Modern typology of symptoms and obsessive-compulsive syndromes: results of a large French study of 615 patients]Encephale199622 Spec No 19218767023

- MurphyDLTimpanoKRWendlandJRGenetic contributions to obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and OCD-related disorders. In: Nurnberger J, Berrettini W, edsPrinciples of Psychiatric Genetics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press 2010

- NestadtGSamuelsJRiddleMAet al.The relationship between obsessive-compulsive disorder and anxiety and affective disorders: results from the Johns Hopkins OCD Family StudyPsychol Med20013148148711305856

- KesslerRCMcGonagleKAZhaoSet al.Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity SurveyArch Gen Psychiatry1994518198279933

- MiguelECFerraoYARosarioMCet al.The Brazilian Research Consortium on Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders: recruitment, assessment instruments, methods for the development of multicenter collaborative studies and preliminary resultsRev Bras Psiquiatr20083018519618833417

- GellerDPettyCVivasFJohnsonJPaulsDBiedermanJExamining the relationship between obsessive-compulsive disorder and attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a familial risk analysisBiol Psychiatry20076131632116950231

- GellerDPettyCVivasFJohnsonJPaulsDBiedermanJFurther evidence for co-segregation between pediatric obsessive compulsive disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a familial risk analysisBiol Psychiatry2007611388139417241617

- AsbahrFRGarveyMASniderLAZanettaDMElkisHSwedoSEObsessive-compulsive symptoms among patients with Sydenham choreaBiol Psychiatry2005571073107615860349

- KirvanCASwedoSEHeuserJSCunninghamMWMimicry and autoantibody-mediated neuronal cell signaling in Sydenham choreaNat Med2003991492012819778

- SwedoSELeonardHLGarveyMet al.Pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: clinical description of the first 50 casesAm J Psychiatry19981552642719464208

- AlvarengaPGHounieAGMercadanteMTet al.Obsessive-compulsive symptoms in heart disease patients with and without history of rheumatic feverJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci20061840540816963592

- de AlvarengaPGFloresiACTorresARet al.Higher prevalence of obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders in rheumatic feverGen Hosp Psychiatry20093117818019269540

- HounieAGPaulsDLMercadanteMTet al.Obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders in rheumatic fever with and without Sydenham's choreaJ Clin Psychiatry20046599499915291690

- MercadanteMTBusattoGFLombrosoPJet al.The psychiatric symptoms of rheumatic feverAm J Psychiatry20001572036203811097972

- HounieAGPaulsDLdo Rosario-CamposMCet al.Obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders and rheumatic fever: a family studyBiol Psychiatry20076126627216616727

- SeixasAAHounieAGFossaluzaVet al.Anxiety disorders and rheumatic fever: is there an association?CNS Spectr2008131039104619179939

- HounieAGCappiCCordeiroQet al.TNF-alpha polymorphisms are associated with obsessive-compulsive disorderNeurosci Lett2008442869018639610

- RamasawmyRFaeKCSpinaGet al.Association of polymorphisms within the promoter region of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha with clinical outcomes of rheumatic feverMol Immunol2007441873187817079017

- SniderLASwedoSEPANDAS: current status and directions for researchMol Psychiatry200490090715241433

- SwedoSEGrantPJAnnotation: PANDAS: a model for human autoimmune diseaseJ Child Psychol Psychiatry20054622723415755299

- HoffmanKLHornigMYaddanapudiKJabadoOLipkinWIA murine model for neuropsychiatric disorders associated with group A beta-hemolytic streptococcal infectionJ Neurosci2004241780179114973249

- LougeeLPerlmutterSJNicolsonRGarveyMASwedoSEPsychiatric disorders in first-degree relatives of children with pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS)J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2000391120112610986808

- ShulmanSTPediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococci (PANDAS): updateCurr Opin Pediatr20092112713019242249

- KurlanRJohnsonDKaplanELStreptococcal infection and exacerbations of childhood tics and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a prospective blinded cohort studyPediatrics20081211188119718519489

- LinHWilliamsKAKatsovichLet al.Streptococcal upper respiratory tract infections and psychosocial stress predict future tic and obsessive-compulsive symptom severity in children and adolescents with Tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorderBiol Psychiatry20106768469119833320

- RizzoRGulisanoMPavonePFoglianiFRobertsonMMIncreased antistreptococcal antibody titers and anti-basal ganglia antibodies in patients with Tourette syndrome: controlled cross-sectional studyJ Child Neurol20062174775316970879

- TermineCUggettiCVeggiottiPet al.Long-term follow-up of an adolescent who had bilateral striatal necrosis secondary to Mycoplasma pneumoniae infectionBrain Dev.200527626515626544

- BudmanCSarcevicAAn unusual case of motor and vocal tics with obsessive-compulsive symptoms in a young adult with Behcet's syndromeCNS Spectr2002787888112766698

- BodeLDurrwaldRRantamFAFersztRLudwigHFirst isolates of infectious human Borna disease virus from patients with mood disordersMol Psychiatry199612002129118344

- CheyetteSRCummingsJLEncephalitis lethargica: lessons for contemporary neuropsychiatryJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci199571251347626955

- ErcanTEErcanGSevergeBArpaozuMKarasuGMycoplasma pneumoniae infection and obsessive-compulsive disease: a case reportJ Child Neurol20082333834018079308

- YaramisAHergunerSKaraBTatliBTuzunUOzmenMCerebral vasculitis and obsessive-compulsive disorder following varicella infection in childhoodTurk J Pediatr200951727519378896

- BerthierMLKulisevskyJGironellALopezOLObsessive-compulsive disorder and traumatic brain injury: behavioral, cognitive, and neuroimaging findingsNeuropsychiatry, Neuropsychol Behav Neurol200114233111234906

- CoetzerRSteinDJDu ToitPLExecutive function in traumatic brain injury and obsessive-compulsive disorder: an overlap?Psychiatry Clin Neurosci200155838711285083

- GradosMAObsessive-compulsive disorder after traumatic brain injuryInt Rev Psychiatry20031535035815276956

- SilverJMKramerRGreenwaldSWeissmanMThe association between head injuries and psychiatric disorders: findings from the New Haven NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area StudyBrain Injury20011593594511689092

- McKeonJRoaBMannALife events and personality traits in obsessive-compulsive neurosisBr J Psychiatry19841441851896704605

- KantRSmith-SeemillerLDuffyJDObsessive-compulsive disorder after closed head injury: review of literature and report of four casesBrain Inj19961055638680393

- RothRMJobstBCThadaniVMGilbertKLRobertsDWNew-onset obsessive-compulsive disorder following neurosurgery for medicationrefractory seizure disorderEpilepsy Behav20091467768019435591

- KurlanRDisabling repetitive behaviors in Parkinson's diseaseMov Disord20041943343715077241

- MaiaAFPintoASBarbosaERMenezesPRMiguelECObsessivecompulsive symptoms, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and related disorders in Parkinson's diseaseJ Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci20031537137412928516

- CorreiaSHubbardEHassenstabJet al.Basal ganglia MR relaxometry in obsessive-compulsive disorder: T2 depends upon age of symptom onsetBrain Imag Behav In press

- RutaLMugnoDD'ArrigoVGVitielloBMazzoneLObsessive-compulsive traits in children and adolescents with Asperger syndromeEur Child Adolesc Psychiatry201019172419557496

- ZandtFPriorMKyriosMSimilarities and differences between children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and those with obsessive compulsive disorder: executive functioning and repetitive behaviourAutism200913435719176576

- BottasACookeRGRichterMAComorbidity and pathophysiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in schizophrenia: is there evidence for a schizo-obsessive subtype of schizophrenia?J Psychiatry Neurosci20053018719315944743

- PoyurovskyMKoranLMObsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) with schizotypy vs. schizophrenia with OCD: diagnostic dilemmas and therapeutic implicationsJ Psychiatr Res20053939940815804390

- SaARHounieAGSampaioASArraisJMiguelECElkisHObsessivecompulsive symptoms and disorder in patients with schizophrenia treated with clozapine or haloperidolCompr Psychiatry20095043744219683614

- JesteDVDolderCRTreatment of non-schizophrenic disorders: focus on atypical antipsychoticsJ Psychiatr Res2004387310314690772

- EisenJLBeerDAPatoMTVendittoTARasmussenSAObsessivecompulsive disorder in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorderAm J Psychiatry19971542712739016282

- PoyurovskyMFuchsCWeizmanAObsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with first-episode schizophreniaAm J Psychiatry19991561998200010588421

- DowlingFGPatoMTPatoCNComorbidity of obsessive-compulsive and psychotic symptoms: a reviewHarv Rev Psychiatry1995375839384932

- FontenelleLFdo Rosario-CamposMCDe MathisMAet al."Posttraumatic" obsessive-compulsive disorder: a neglected psychiatric phenotype? Inaugural Scientific Meeting of the International College of Obsessive Compulsive Spectrum Disorders. Barcelona, Spain 2008

- GershunyBSBaerLRadomskyASWilsonKAJenikeMAConnections among symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: a case seriesBehav Res Ther2003411029104112914805

- Dias-FerreiraESousaJCMeloIet al.Chronic stress causes frontostriatal reorganization and affects decision-makingScience200932562162519644122

- GuillemFSatterthwaiteJPampoulovaTStipERelationship between psychotic and obsessive compulsive symptoms in schizophreniaSchizophr Res200911535836219560321

- PaulsDLThe genetics of obsessive compulsive disorder: a review of the evidenceAm J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet2008148C13313918412099

- NicoliniHArnoldPNestadtGLanzagortaNKennedyJLOverview of genetics and obsessive-compulsive disorderPsychiatry Res200917071419819022

- SamuelsJFRecent advances in the genetics of obsessive-compulsive disorderCurr Psychiatry Rep20091127728219635235

- GradosMWilcoxHCGenetics of obsessive-compulsive disorder: aresearch updateExpert Rev Neurother2007796798017678492

- BlochMHLanderos-WeisenbergerASenSet al.Association of the serotonin transporter polymorphism and obsessive-compulsive disorder: systematic reviewAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet2008147B85085818186076

- WendlandJRDeGuzmanTBMcMahonFRudnickGDeteraWadleighSDMurphyDLSERT Ileu425Val in autism, Asperger syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorderPsychiatr Genet200818313918197083

- ZhangHLeckmanJFPaulsDLTsaiCPKiddKKCamposMRGenomewide scan of hoarding in sib pairs in which both sibs have Gilles de la Tourette syndromeAm J Hum Genet20027089690411840360

- ShugartYYSamuelsJWillourVLet al.Genomewide linkage scan for obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence for susceptibility loci on chromosomes 3q, 7p, 1q, 1 5q, and 6qMol Psychiatry20061176377016755275

- SamuelsJFBienvenuOJGradosMAet al.Prevalence and correlates of hoarding behavior in a community-based sampleBehav Res Ther20084683684418495084

- SamuelsJFBienvenuOJPintoAet al.Sex-specific clinical correlates of hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorderBehav Res Ther2008461040104618692168

- GrishamJRBrownTALiverantGICampbell-SillsLThe distinctiveness of compulsive hoarding from obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Anxiety Disord20051976777916076423

- FrostROSteketeeGWilliamsLFWarrenRMood, personality disorder symptoms and disability in obsessive compulsive hoarders: a comparison with clinical and nonclinical controlsBehav Res Ther2000381071108111060936

- GothelfDPresburgerGZoharAHet al.Obsessive-compulsive disorder in patients with velocardiofacial (22q1 1 deletion) syndromeAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet20041269910515048657

- FeinsteinCEliezSBlaseyCReissALPsychiatric disorders and behavioral problems in children with velocardiofacial syndrome: usefulness as phenotypic indicators of schizophrenia riskBiol Psychiatry20025131231811958782

- PapolosDFFaeddaGLVeitSet al.Bipolar spectrum disorders in patients diagnosed with velo-cardio-facial syndrome: does a hemizygous deletion of chromosome 22q11 result in bipolar affective disorder?Am J Psychiatry1996153154115478942449

- PulverAENestadtGGoldbergRet al.Psychotic illness in patients diagnosed with velo-cardio-facial syndrome and their relativesJ Nerv Ment Dis19941824764788040660

- Saunders-PullmanRShribergJHeimanGet al.Myoclonus dystonia: possible association with obsessive-compulsive disorder and alcohol dependenceNeurology20025824224511805251

- DohenyDDanisiFSmithCet al.Clinical findings of a myoclonus-dystonia family with two distinct mutationsNeurology2002591244124612391355

- MarechalLRauxGDumanchinCet al.Severe myoclonus-dystonia syndrome associated with a novel epsilon-sarcoglycan gene truncating mutationAm J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet200311911411712707948

- ZimprichAGrabowskiMAsmusFet al.Mutations in the gene encoding epsilon-sarcoglycan cause myoclonus-dystonia syndromeNat Genet200129666911528394

- VerkerkAJMathewsCAJoosseMEussenBHHeutinkPOostraBACNTNAP2 is disrupted in a family with Gilles de la Tourette syndrome and obsessive compulsive disorderGenomics2003821912809671

- Boghosian-SellLComingsDEOverhauserJTourette syndrome in a pedigree with a 7;18 translocation: identification of a YAC spanning the translocation breakpoint at 18q22.3Am J Hum Genet19965999910058900226

- PetekEWindpassingerCVincentJBet al.Disruption of a novel gene (IMMP2L) by a breakpoint in 7q31 associated with Tourette syndromeAm J Hum Genet20016884885811254443

- Diaz-AnzalduaAJooberRRiviereJBet al.Association between 7q31 markers and Tourette syndromeAm J Med Genet A2004127172015103711

- BihariKHillJLMurphyDLObsessive-compulsive characteristics in patients with idiopathic spasmodic torticollisPsychiatry Res1992422672721496058

- BihariKPigottTAHillJLMurphyDLBlepharospasm and obsessivecompulsive disorderJ Nerv Ment Dis19921801301321737975

- DefazioGLivreaPEpidemiology of primary blepharospasmMov Disord20021771211835433

- MarksWAHoneycuttJAcostaFReedMDeep brain stimulation for pediatric movement disordersSemin Pediatr Neurol200916909819501337

- Hoehn-SaricRNinanPBlackDWet al.Multicenter double-blind comparison of sertraline and desipramine for concurrent obsessive-compulsive and major depressive disordersArch Gen Psychiatry200057768210632236

- MatsumotoRIchiseMItoHet al.Reduced serotonin transporter binding in the insular cortex in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a [11C]DASB PET studyNeuroimage20104912112619660554

- MacMasterFPO'NeillJRosenbergDRBrain imaging in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorderJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry2008471262127218827717

- Mataix-ColsDWoodersonSLawrenceNBrammerMJSpeckensAPhillipsMLDistinct neural correlates of washing, checking, and hoarding symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorderArch Gen Psychiatry20046156457615184236

- ChamberlainSRMenziesLEndophenotypes of obsessive-compulsive disorder: rationale, evidence and future potentialExpert Rev Neurother200991133114619673603

- HajcakGFranklinMEFoaEBSimonsRFIncreased error-related brain activity in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder before and after treatmentAm J Psychiatry200816511612317986681

- BedardMJJoyalCCGodboutLChantalSExecutive functions and the obsessive-compulsive disorder: on the importance of subclinical symptoms and other concomitant factorsArch Clin Neuropsychol20092458559819689989

- JoshiGWilens TTChild Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am20091829131919264265

- WelchJMLuJRodriguizRMet al.Cortico-striatal synaptic defects and OCD-like behaviours in Sapap3-mutant miceNature200744889490017713528

- ZuchnerSWendlandJRAshley-KochAEet al.Multiple rare SAPAP3 missense variants in trichotillomania and OCDMol Psychiatry2009146919096451