Abstract

This article aims to explore the relevance and importance of school subjects in teachers’ grading practices, as teachers themselves see it. The study is based on material from 41 semi-structured interviews, with teachers of five subjects, at four lower and two upper secondary schools in Norway. The findings suggest that the school subject does matter when teachers assign final grades to their students. The study also indicates that different subjects involve different challenges or obstacles in fulfilling government recommendations and regulations for grading. A four-part model is developed that summarises the subject differences found in teachers’ approaches to grading, and which allows different subjects to be mapped relative to one another. These findings seem to support arguments that more recognition should be given to differences between school subjects, and the influence of contextual dimensions in grading practices. This is particularly relevant in implementing system-wide changes such as the creation of unitary systems for the measurement of student learning outcomes.

Tine S. Prøitz is a researcher at NIFU (Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education) and a PhD candidate at the University of Oslo in Norway. Her professional interests cover studies of learning outcomes as a conceptual phenomenon at the intersection between education, quality and accountability and studies of educational reform.

Introduction

At a time when grades and test scores are used as indicators of learning outcomes for accountability purposes and for national and international benchmarking (Lawn Citation2011:278), grading is becoming an important issue in a new and different way. Grading is no longer simply a matter of teachers assigning grades to students in a consistent and fair manner at the individual school level: it has become the basis of national, as well as international measurement, comparison and concern. It is well documented that teachers assign grades in ways that diverge from recommended grading practices, sometimes at the expense of their interpretability (Stiggins & Conklin Citation1992, Brookhart Citation1991, Citation1993 Citation1994). Issues of validity due to these variations in teachers’ grading practices have been discussed for some time (Brookhart Citation1993, Allen Citation2005, Harlen Citation2005). Increased awareness of this issue has led to the introduction of an array of measures such as standards, criteria, tests and other forms of external audits, which are intended to help and/or control teachers’ final grading so it complies with current policy. Within a framework of multidimensional purposes and uses of final grades, new requirements for the standardisation of grading practices are being introduced by governments, including the Norwegian one. This may further complicate processes for grading and could even destabilise established ideas about what a valid grade is.

Norway has a long and unusual tradition of scepticism regarding formal assessment and grading, which has resulted in frequent changes in grading scales and the troublesome introduction of new directives (Lysne Citation2006:330). The practice of assessing student performance according to predefined goals and standards is relatively new in Norway where a strong tradition of process orientation has predominated, and where teachers have assigned final grades to their own students from Year 8 through Year 13 (Engelsen & Smith Citation2010:417, Hertzberg Citation2008, Skedsmo Citation2011, Telhaug et al. 2004). Implemented in 2006, the latest educational reforms have changed the regulations for final gradingFootnote1. Among other things, teachers are now expected to assign final grades based solely on performance and knowledge, while previously they were also expected to consider student effort, attitude and participation. This involves a shift in the understanding of the role of final grading: from a tradition where grading was seen as assessment for learning, to grading being used as an assessment of learning. In this way, schooling in Norway is in the process of changing from being mainly process-oriented to more results-oriented.

Investigations of teachers’ grading practices have found evidence that teachers assign grades differently in various subjects (Resh Citation2009, Duncan & Noonan Citation2007, Lekholm & Cliffordson Citation2009, McMillan 2001). Teachers’ socialisation and professional development are also influenced and differentiated by their subject or disciplinary focus. Variations in the structure and nature of subject matter affects decisions on content to be taught and pedagogical patterns used in teaching and patterns of student evaluation (Resh Citation2009:318). Nevertheless, the relationship between teachers’ grading practices and subjects has not been well articulated (Duncan & Noonan Citation2007:3). This raises questions around the introduction of common frameworks of recommendations and regulations for grading: Can variation in teachers’ grading practices be better understood when seen in the light of the subjects they teach; is it possible or suitable to use a common framework for all subjects? Which implications may this hold for the validity of the grades?

This article aims to explore the relevance and importance of school subjects in teachers’ grading practices as teachers themselves see itFootnote2. It focuses on three research questions:

How do teachers approach grading in different school subjects?

How do the grading practices in the different subjects correspond to the recommendations and regulations for grading?

What are the implications for the validity of indicators of learning outcomes based on students’ grades?

In order to answer the first research question, the elements of assessment set out by Harlen (Citation2005:207) will be explored: What is considered relevant evidence for final grading? How is evidence collected, interpreted and communicated? To answer the second research question, the findings from the first research question are considered in light of the revised Norwegian recommendations and regulations for grading. The third research question will be addressed on the basis of findings relating to the two previous research questions.

The article is organised in four sections. An introduction to the topic and the research questions is followed in the second section by a discussion of the theoretical framework and the methodological approach. The third section presents and discusses the findings, leading into conclusions and implications in section four.

Theoretical framework

The research literature on variation in assessment practices offers several explanations. It has been suggested that recommended assessment practices are based on a theoretical foundation of measurement that diverges from the classroom situation (Stiggins et al. Citation1989, Brookhart Citation1994). For example, when recommended practice is to focus solely on performance and not on effort, teachers may view this as irrelevant advice for the real classroom situation (Airasian & Jones Citation1993). Others have challenged the incoherencies between perspectives of learning and those of assessment (Shepard Citation2000, Lundahl Citation2006). Yet another explanation concerns current policy developments described as part of the “assessment reform”, which is characterised by: “1) the rise of large scale assessment and 2) changes in classroom assessment practices” (Duncan & Noonan Citation2007:1, Melograno Citation2007). Duncan and Noonan (Citation2007) question whether teachers have the training and competence required to meet the expectations of the assessment reform.

The particular role of subject domain in grading has been discussed and recognised in several studies (Eggen Citation2004, Lekholm & Cliffordson Citation2009, Citation2008, Duncan & Noonan Citation2007, Resh Citation2009). One explanation for the different grading practices relates to the different epistemological and ideological positions teachers hold concerning assessment (Eggen Citation2004:480). Eggen states that the implicit or explicit ideology of each subject influences teachers’ view of learning and their attitudes to assessment (2004:479). Based on comparisons of teachers of English, science and mathematics, it has been suggested that maths and science teachers tend to view their subjects as having unique and objectively defined goals, while English teachers employ a range of goals that may be appropriate for a particular student at a particular time (Black et al. Citation2003:68).

School subjects may be regarded as the basis on which teachers construct frameworks for assessing achievement and developing grading practices. According to Wiliam (Citation1996), inferences made in assessment are related to the subject domain in question, as well as to other subject domains. As a consequence, Wiliam argues that in processes of validation inferences from and consequences of assessments must be addressed both within and beyond domains (1996:142). In accordance with this, Harlen (2006:48) points out that assessment needs to take account of how subject domains are structured and which methods and processes characterise practice in each field. Harlen also claims that the validity of the assessment process is anchored in the alignment of assessment with learning, teaching and content knowledge, and emphasises that this relationship is not straightforward and should not be taken for granted (2006:47).

Final grades can be regarded as inferences drawn from a body of evidence. As such, the quality of the inferences drawn is important. Allen states that “Validity addresses the accuracy of the assessment and grading procedures used by teachers” (2005:1). Messick underlines: “Validity is not a property of the test or assessment as such, but rather the meaning of the test scores” (1995:741). Messick's unified validity concept enhances the complexity of what is to be assessed and highlights questions concerning the constructs defining relevant assessment areas (Lekholm & Cliffordson Citation2008, Brookhart Citation1993). Lekholm and Cliffordson (Citation2008:184) point out the importance of avoiding “… two major threats to construct validity, namely construct-irrelevant variance and construct underrepresentation”. In other words, it is important to ensure that grades are not grounded in constructs other than those intended and that grades adequately cover the intended constructs This makes the constructs used in teachers’ grading practices a crucial issue for the validity of resulting grades.

Tyack and Tobin (Citation1994:457) have pointed out that both the ‘grammar’ of schooling (the “regular structures and rules that organise the work of instruction”) and the teaching within it are historical products that are highly resistant to change.

Muller's (Citation2009:210) examination of the roots of disciplinary differences shows how certain “fault lines” continue to influence the patterns of disciplinary divisions and difference, both in universities and in school curriculum development. He points out that the relationship between disciplines as practised in universities and curriculums for schools is evidently not one and the same. On the contrary, he argues that curriculums represent a mixture of different qualities, such as hard-soft and pure-applied typologies, and characteristics such as conceptual and contextual coherence. A curriculum with conceptual coherence is typically characterised as involving vertically ordered, sequential content, and having a strong hierarchy of abstraction and conceptual difficulty. In contrast, contextual coherence is characterised as involving various segments which are well connected but less vertical and sequential: “each segment is adequate to a context sufficient to a purpose” (Muller Citation2009:216). According to Muller (Citation2009), different disciplines require different degrees of conceptual coherence, and the more conceptual coherent the curriculum is, the more formal its set of curriculum requirements will be. The more segmented the curriculum, the less sequence matters, but the more contextual coherence to context matters; for example, external requirements may be of greater interest in certain contexts (2009:216). It is also relevant to note that the greater the conceptual coherence, “the clearer the knowledge signpost must be, both illustratively and evaluatively” (Muller Citation2009:216).

In considering how school subjects are categorised, it is also interesting to examine how they are perceived and labelled in policy and by society at large. For example, arts and craft and physical education are often referred to as supportive subjects, compared unfavourably to “more important” core subjects (Prøitz and Borgen Citation2010:26). Further, such supportive subjects are often presumed to be more practical and core subjects more theoretical (Prøitz and Borgen Citation2010:26).

The complexities in the grouping and definition of various subjects underscores that different disciplines provide different foundations and justifications for their contribution to the school curriculum. In addition, school subjects may have different links to their ‘parent’ disciplines. Taken together, this can lead to variations in practice. Labels such as core/supportive and theoretical/practical may signify differences between school subjects with regard to their function and hence their status in education. This may be observed, for example, in how a society prioritises certain subjects for formal assessmentFootnote3. Teachers’ grading practices may also reflect varying conceptions about the function and status of subjects in the national curriculum relative to one another.

Empirical Context and Methodological approach

Much of the research literature on teachers’ grading practices is based on quantitative data (Brookhart Citation1993, Citation1994, Lekholm & Cliffordson Citation2008, Citation2009, Duncan & Noonan Citation2007, Melograno Citation2007, Resh Citation2009). Less work has explored how teachers think about their own grading practices in different school subjects. A qualitative approach has therefore been chosen for this investigation. This study draws upon data from 41 semi-structured individual interviews with teachers in five subjects, at four lower secondary schools and two upper secondary schools.

The context of the study

Throughout Norway's history, the development of the national curriculum has been considered an important measure for nation-building and the creation of the social democratic welfare state, often referred to as the Nordic model (Karseth & Sivesind Citation2010:104, Telhaug et al. 2004). For example, the function of Norwegian as a school subject goes well beyond teaching reading and writing skills: it is a central subject for passing on cultural values. Using Muller's terms (Citation2009), the curriculum for Norwegian is marked by a high degree of contextual coherence. In contrast, the curriculum for mathematics is more conceptual, although certain aspects of the subject have been emphasised over others, for contextual reasons and at different times. Both Norwegian and mathematics are labelled as core subjects and considered to be more theoretical than arts and craft or physical education, which are regarded as supportive and as more practical (Prøitz & Borgen Citation2010:26). Following this line of thinking, science is positioned as an ‘in-between’ subject. The individual science subjects – biology, chemistry and physics – have a high degree of conceptual coherence, but the disciplinary area of science these make up covers a very broad thematic field, ranging from ecology to drug abuse. Similarly, the subject arts and craft seem to have several functions, from developing knowledge of art within a national cultural context to nurturing creativity and developing practical skills. Physical education seems to be a subject with a built-in tension by aiming to teach skills and nurture performance in sports, while also supporting the national and cultural ambition of encouraging students to live a healthy lifestyle. As this study investigates teachers’ grading practices in five subjects in Norway it is important to underscore that subjects in other countries may relate differently to Muller's concepts of contextual and conceptual coherence.

Most of the grades students receive on their school leaving certificate (received at the end of compulsory schooling, on completion of Year 10) and on their Certificate of Upper Secondary Education (received on completion of Year 13) have been decided by their own teachers, primarily based on classroom assessment. Classroom assessment mainly consists of judging the performance of students on an ongoing basis and using teacher-made tests; there is no tradition of multiple-choice testing (Hertzberg Citation2008). The education system therefore relies on teachers being able to make fair assessments of student performance. Further, as grades are used for selection purposes, the assumption that grades are comparable, reliable and valid has important consequences for students and higher levels of education. The recent changes in policies for teachers’ grading practices raise important new questions about these assumptions.

Sample and selection strategy

The overall sampling strategy used in this study is based on Yin's (Citation1994) exemplary case approach. The purpose of the exemplary sampling strategy is to select cases that function as an example of larger patterns. This study focuses on what can be considered typical within the Norwegian context and so focuses on including schools, subjects and informants that represent a balanced variety with respect to certain key parameters.

The starting point for selection is the school level. The schools selected for this study are located in three different counties in the eastern part of southern Norway. They vary with regard to dimensions of age, to what degree they focus on assessment, size (numbers of teachers and students) and geographical location in terms of proximity to a city centre.

Detailed guidelines were used to select school subjects as these represent a key variable which is central to the research questions. The subjects were selected to offer a broad range of perspectives on assessment and differing grading practices, to build in contrasts that allow for a clearer comparative analysis and identification of variations. As previous studies have indicated that there may be especially clear differences in grading practices between mathematics and other school subjects, it was important to include mathematics alongside other subjects (Black et al. Citation2003). Further selections were influenced by the established classification of school subjects as ‘core’ and ‘supportive’, and led to the inclusion of subjects that fall within both labels. For comparative reasons, it was important to include subjects that have written national examinations (Norwegian and mathematics) as well as subjects that do not (science, arts and craft, physical education). To be able to identify any potential effect of the grade level (year), school subjects taught in both lower and upper secondary education were includedFootnote4. Based on these considerations, the study encompasses five school subjects: Norwegian, mathematics, physical education, arts and craft, and science.

Table I Selection strategy; ffiive school subjects in lower and upper secondary school

The selection of school subjects determined the selection of informants as the main focus was interviews with school subject teachers. The term “school subject teacher” in this study refers to informants responsible for teaching and assigning grades in a particular school subject. The teachers interviewed are typically responsible for teaching several subjects at their schools, but these subjects are usually within the same field such as maths and natural science, or languages.

The principal at each selected school helped arrange contact between the interviewers and informants. The other characteristics of the informants vary in terms of their age, experience as a teacher, gender, degree of training and formal competence in grading. The total sample consisted of 41 teachers: 19 from lower secondary schools and 22 from upper secondary schools. Slightly more than half (24) are women. The distribution of those interviewed is balanced across the selected school subjects, educational levels and the six schools.

Qualitative interview procedures

The interviews were conducted at the informants’ ‘home base’, i.e. their schools, and in an informal conversational style. The informants were asked to focus on their grading practice within the particular subject in question. The informants often responded to this by explicitly contrasting their practice between different subjects throughout the interviews. The questions and topics covered were based on a semi-structured interview guide. The guide was organised around an opening question asking the informant to describe and exemplify how they proceed when grading students. Other questions concerned the kind of evidence and tools informants employ when grading, how and why they use them, what they think about their own grading practices, and whether and how they ensure that grades are just and fair. Based on the assumption that it would be hard to get teachers to be specific enough (McMillan Citation2003), a grading experiment involving weighting was also added to the interview guide. This grading experiment was presented on a separate piece of paper, when issues concerning weighting naturally emerged during the interview. All interviews were taped with an audio recorder and transcribed.

In analysing the material, patterns of differences and similarities were identified according to the analytical framework. In this way, the coding and analysis can be characterised as partly concept-driven, using codes developed in advance based on existing literature in the field (Kvale and Brinkman Citation2009:202). However, the analysis was also partly data-driven as additional codes were developed through the process of repeated reading of the material. This study involved several phases: first, an inductive investigation followed by a more deductive investigation and, finally, extensive interpretations and theoretical analysis (Kvale and Brinkman Citation2009:207).

The research literature on grading practices has identified a number of factors or elements involved in teachers’ judgments of student work in general (Harlen Citation2005, Sadler 1998). More specifically, Melograno (Citation2007) and Resh (Citation2009) suggest that grading involves weighting elements of student behaviour. A key portion of the conceptual framework employed in this investigation is inspired by, and based on, a combination of the concepts of weighting put forward by Melograno and Resh.

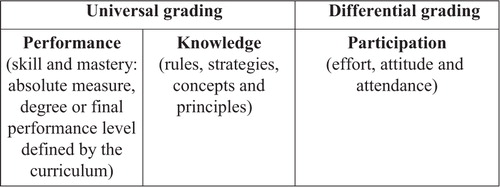

Melograno (Citation2007:46–47) suggests that assigning a final grade in physical education involves weighting (through differentiation of importance) factors of student behaviour. He divides student behaviour into three main factors: performance (skills), knowledge (rules, strategies, concepts and principles), and participation (attendance, attitude and effort). Resh (Citation2009) adopts a similar concept in a study of teachers’ perspectives on grade allocation in languages, mathematics and science. Resh identifies three main categories of factors that teachers consider in grading: performance (ability and academic success), effort (learning and class behaviour), and need (need for encouragement) (2009:319). Resh also distinguishes between universal and differential grading. These concepts are rooted in a wider discussion about the fair allocation of teachers’ attention in classrooms, and the pros and cons of equal or differential allocation of time for stronger and weaker students (Resh Citation2009:318). Resh explains this tension: “On the one hand, teachers are expected to treat students equally and to apply universal criteria in learning demands and in evaluation of its outcome” (Resh Citation2009:318), but they are also asked to be aware of individuals’ needs and to adjust the pedagogical activity accordingly. According to Resh, this results in differential treatment where teachers’ concern with and efforts at understanding different needs may be reflected in their assessment practices and the grades they allocate.

By supplementing Melograno's three elements of student behaviour (performance, knowledge and participation) with Resh's universal and differential treatment, the framework covers both aspects of teachers’ weighting elements based on student behaviour and teachers’ conceptions of just and fair grading practices.

The placement of performance and knowledge under the label universal grading builds on the assumption that these categories are conceived to be ‘purer’ and easier to measure than participation, which is understood as a category that facilitates differential grading. In systems (like the Norwegian systemFootnote5) where students are supposed to be assessed solely on the basis of performance and knowledge, differential grading is likely to be found in aspects of assessment concerning participation.

The conceptual framework of weighting based on Melograno (Citation2007) and Resh (Citation2009) functions as a tool for categorising data at the school level. However, the material also needs to be considered within a larger contextual framework in order to address the research questions. The contributions from Muller (Citation2009) and the national context of the investigation open up space for a broader analytical view. Muller's work sets out the ways in which subjects might differ fundamentally in their composition and therefore in their curricular status and assessment. The national situation makes these issues ever more relevant to both classroom practice and policy debates as both assume a level of ‘neutrality’ in grading between subjects that may be questionable.

Findings

The presentation of the findings of this investigation follow the structure of the research questions, starting by setting out what is considered relevant evidence and how it is collected and moving on to consider how it is interpreted and communicated.

Relevant evidence for grading in five subjects

When asked to describe the kind of evidence they regard as the most important when grading, informants list a variety of common sources: tests and assignments, written hand-ins, reports, oral presentations, pre and post-tests of skills, reflection notes, informal formative tests, products of practical assignments and, finally, teachers’ impressions of students’ work. Such a wide variety reflects different approaches to teaching and differences between subjects in particular. The various approaches to relevant evidence fall into two categories:

The narrow approach is dominated by the use of written tests and assignments in sessions lasting two hours or more. Informants report that they use example exams with marking guidelines, available from the Norwegian Directorate of Education and Training's website. The use of these example exams usually takes place at the end of the school year and constitutes one of the most important kinds of evidence for final grading in Norwegian and mathematics.

The broader approach typically involves the use of a wider selection of evidence for grading. In science, informants use traditional knowledge tests combined with a certain number of science reports to be handed in by students; student performance in class is also considered important. Informants in arts and craft combine knowledge assignments with their own notes on student performance in class and students’ reflection notes on the work they complete in a specific practical assignment at the end of the school year. In physical education, informants use pre- and post-skill tests, notes on student performance in class and students’ own reports on a self-directed physical training project that are handed in at the end of Year 10 and Year 13.

In addition to these main sources of evidence, the informants point out that they also use other supplementary sources of a more informal kind to support their decisions, especially when in doubt. The two approaches presented above suggest that certain differences between subjects are related to the use of national written examinations. Teachers in Norwegian and mathematics rely heavily on example exams, while in subjects without such exams (science, arts and craft, physical education) informants use a wider selection of evidence.

Interpretation of evidence – the importance of tools

Teachers are required to use the national curriculum to develop a local curriculum and tools for assessment at their schools. The government has also emphasised the importance of establishing common cultures across schools, based on sharing and collaboration in assessment. The informants in this study describe wide-ranging processes for developing local curriculums, guidelines, frameworks, standards, criteria etc. to support their grading work. They also describe various practices used for collaboration. Three distinct approaches to the interpretation of evidence in grading have been identified.

Calculation of points: “I am a slave to my tool!”

Teachers in mathematics and science consider grading to be easier than those in other school subjects. They explain this in reference to an established tool for grading: the calculation of points when scoring tests. They rely on systems that have been developed to calculate points for different items and tasks in tests, with a specific range of points then corresponding to grades in the grading scale. Informants in both mathematics and science report a low degree of collaboration in grading; this may involve only a single meeting at the beginning of the school year to discuss which tests to use at what time of the year. Some informants report that they collaborate on developing these tests. Informants typically refer to their grading tools as a standard which leaves little room for alternative interpretations, and therefore ensures both a criterion-referenced approach and fairness in grading. However, the material indicates that the calculation of points is not necessarily conducted consistently by all of the informants. Informants in mathematics point out that the degree of difficulty of various items is an issue of debate. Nevertheless, on the whole, informants in mathematics and science perceive the calculation of points as providing a standardised system that helps them to assign grades in a fair and consistent way.

Assessment community – as an ideal tool and a real tool

In Norwegian and arts and craft, informants describe final grading as a difficult part of their job. They are concerned about their ability to judge their students justly and consistently and about taking more of a norm-referenced approach. They have developed tools for assessment and grading to a varying degree. One such tool involves detailed written descriptions of competency aims in the national curriculum, which have been broken down into smaller, more assessable segments. Nevertheless, on the whole, informants report that the basis for final grading in their subjects will always be open to alternative interpretations, to a certain extent. The teachers explain that their primary strategy for ensuring qualitatively good final grading practices is taking part in a subject-based assessment community. Such a community ideally involves some common, negotiated and agreed-upon standards of student performance. These communities work differently in practice for Norwegian teachers and arts and craft teachers. Norwegian teachers report that they have some meetings to discuss tools for the interpretation of test results, but that their meetings generally focus on planning dates for setting exams and discussing how to apply guidelines provided for scoring the exams. Teachers of Norwegian also report they have too little time to collaborate, and that they are most likely to discuss student performance with colleagues when they are in doubt about which grade to assign. On the other hand, informants from arts and craft describe a strong assessment community where conducting assessments together and discussing the students’ final grades is a natural and central practice. Informants point out that having an agreed-upon standard is still very important to their final grading. Cooperation with fellow teachers when assigning final grades is perceived as crucial to just and fair grading in arts and craft.

Performance tests and personal professional judgement

Informants in physical education underline that final grading is difficult and is based on a high degree of personal, professional judgment (based on their experience as a teacher). Nevertheless, the use of pre- and post-skill tests with predefined standards is widespread. These comprise tests of physical fitness such as those measuring how far students can run in a defined time (the Cooper test) or how fast students can run a certain distance (the 60-metre test). These tests come with predefined and fixed standards for student performance and account almost directly for assessment within certain areas of the subject. On the other hand, the informants stress the importance of understanding that for some students running 200 metres in a post-test is an excellent performance if the student had not run at all in the pre-test. Typically, informants in physical education do not believe it is possible to give completely just and fair grades to all. Informants report a low degree of collaboration and discussion when grading. Some report collaboration in planning the timetable for assessments, while others had participated in meetings concerning criteria development. However, in general, a lack of time is considered to be an obstacle to collaboration.

Interpretation of evidence – weighting

This section refers to the results of the grading experiment employed in the interviews. The informants were asked to describe how they would weigh the three elements of the conceptual framework – performance, knowledge and participation – against one another when assigning final grades to stronger and weaker students in a grading situation. When responses to this experiment are compared between school subjects, diversity in weighting is evident.

Informants in mathematics and science explain that because of the tools they use (calculation of points) they seldom consider elements other than performance and knowledge when assigning final grades. Some exceptions are made, however. Science teachers sometimes give weaker students more leeway, especially if they have shown very good progression during the school year; they also point out that their diverse base of evidence opens up space for consideration of elements other than performance and knowledge, such as neatness and other aesthetic factors in science reports.

Like the informants in mathematics, the informants in arts and craft say they have a strong performance and knowledge orientation. Few informants describe situations in which they would take the element of participation into consideration when grading weaker students. However, the informants describe a feeling of sadness about the fact that they have had students with a high degree of participation in all aspects of the subject, but who did not have the academic performance and knowledge required to obtain a higher final grade. These informants complain that the revised Act from 1998 (no. 61, issued on 17 July 1998) shuts the door on rewarding students with a high degree of participationFootnote6.

Informants in Norwegian are the most open to taking all three elements into consideration when assigning final grades to weaker students.

Informants in physical education represent an exception as they report that they take the element of participation into consideration for all students, stronger and weaker alike. These informants also regard each student's effort as important since they believe that students who invest tremendous effort will eventually achieve a high performance.

Communication of evidence – use of the grading scale

The Norwegian grading scale runs from 1 to 6, where 1 is a fail and 6 is the highest possible grade. The informants were asked how they use the grading scale, and distinct differences emerged. Two main approaches were identified amongst the teachers: 1) all six grades are used; and 2) four to five grades are used. Informants who report that they use all six grades were typically school subject teachers in mathematics, science or arts and craft. For mathematics teachers in particular, the tool employed (calculation of points) supports this approach: students who receive the lowest possible number of points receive grade 1 and fail. In general, subject teachers in Norwegian and physical education report that they do not use grade 1, and some informants also reported seldom assigning grade 6. Teachers in Norwegian point out that they “hunt for grade 2 students” because “… everybody knows something in Norwegian”.

Summary of findings

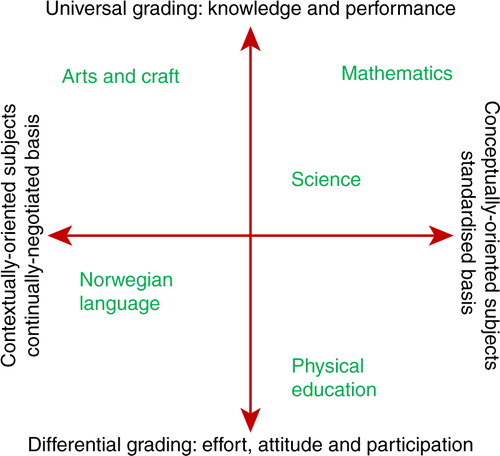

The informants’ reported treatment of evidence in grading (relevant evidence and tools) may be clustered into two broadly defined categories linking back to the typology Muller (Citation2009) set out. Teachers within more conceptual subjects seem to treat their evidence for grading in a more standardised way while teachers within subjects that are more contextual treat their evidence for grading as more open to continuous negotiation. Likewise, the informants’ interpretation and communication of evidence may be clustered into two aspects of just and fair grading – universal grading (equal for all) and differential grading (adjusted to student needs). Together, these clusters may form two continuums in a model of four quadrants capturing variation in both the treatment of evidence and approaches to fairness in grading, providing grounds for the discussion to follow.

Informants in arts and craft describe a grading practice based on a culture of strong assessment communities, which provide a shared standard and a universal grading approach whereby students are primarily rewarded on the basis of their performance and knowledge. All six grades are typically in use. However, informants describe a feeling of sadness because they cannot reward students who have a high degree of participation but low academic performance.

Informants in science and mathematics refer to the calculation of points as important for assigning final grades. They view this tool as a standard that ensures fairness and universality in grading. Informants in science have slightly different grading practices due to the fact that they employ a more diverse evidence base for final grading. All six grades are in use.

Informants in Norwegian primarily employ a continually negotiated approach to final grading. Although they aspire to an ideal of collaboration in assessment communities, they report that they are most likely to discuss grading with colleagues when they are in doubt. They are the most open to using a differential approach and taking participation into consideration for weaker students. Grades 2–5 (and sometimes 6) are typically in use.

Informants in physical education generally employ a standardised basis for grading based on pre- and post-skill tests with predefined standards of performance. However, they see their personal professional experience as an important tool for just and fair grading, and therefore regard all three elements (performance, knowledge and participation) as important for all students. Grades 2–6 are in use.

Discussion

The material reveals distinct differences among the five subjects in what informants consider to be relevant evidence for grading and how they collect, interpret and communicate evidence of student performance. These differences suggest that school subjects do matter in grading.

The findings indicate that informants have a strong internal sense of how things should be done within their school subject in terms of grading and what constitutes relevant evidence. On the other hand, teachers find it harder to value or weigh up evidence and the approach they use seems to depend greatly on the school subject. The study has identified two main approaches to the interpretation of evidence: a standardised approach and a continually negotiated approach. According to the informants, the former is characterised by tools that provide a fairly direct influence on grades, involving incontestable measures of student performance. The latter is characterised by tools that are open to alternative interpretations, making negotiation between colleagues important to reach an agreed-upon standard. School subjects seem to have different frameworks that relate to these variations; some are more restricted, making more direct measurement possible, while others are more open. Teachers in school subjects with a more open framework handle grading in various ways; some develop strong practices of assessment based on collaboration and commonly agreed standards, while others deal with it by questioning or rejecting the ideal of fair and just grading overall.

The coherence of school subjects and open or restricted frameworks for grading

Differing patterns of conceptual and contextual coherence in school subjects have been described by Muller (Citation2009) and the categories and contrasts he sets out seem useful in this case. The findings suggest that school subjects with high conceptual coherence and a strong link to their parent disciplines (which tend to have a clear structure, involving hierarchical and sequenced elements) provide teachers with “clearer knowledge signposts” (Muller Citation2009), enabling them to develop tools that help them to comply with government regulations and make them more confident in their grading practice. Conversely, school subjects with high contextual coherence and weaker links to their parent disciplines (which tend to be less hierarchical and sequential and more segmented) appear to require a strong culture of collaboration in grading to give teachers the confidence they need in their practice.

Informants in school subjects with a high degree of standardisation (mathematics, science) assign grades within a more restricted framework, with less room for alternative interpretations of evidence, and thus employ a clearly defined construct in grading. Informants in school subjects that entail continual negotiation have a more open grading practice, and so seem to employ a less clearly defined construct. The informants regard the restricted framework of mathematics and science as essential to ensuring fair and just grading. However, questions about the validity of the inferences drawn from the chosen evidence remain. In mathematics in particular, the narrow range of evidence, consisting of test results and the results of the example exam, may actually lead to construct underrepresentation and the risk of grading on an overly narrow basis. Conversely, more open grading practices (as found in Norwegian, physical education) may capture aspects of the students which strengthen the validity of teachers’ inferences, but which simultaneously introduce a risk of construct-irrelevant variance as teachers might take irrelevant aspects of performance or behaviour in grading into account.

Constructs of validity and the difficulties of student participation in grading

The validity of grades depends on the constructs from which inferences are drawn. The discussion above reflects the fact that the material has been reviewed in light of the construct stipulated by government legislation amended in 2009. However, the investigation indicates that the grading practices of teachers in different subjects are based on varying constructs. Among other things, the desire of all informants in all subjects to take the element of participation into consideration when grading, albeit to a varying degree, indicates that teachers regard this as an important element that is not sufficiently acknowledged by the official construct. It may also reflect a clash between the constructs of grades developed for unitary systems and their associated regulations, and the constructs of grades held by teachers as professionals within different school subjects. Even informants in mathematics report that they take participation into consideration for weaker students, thereby questioning the universality of their own standards. Informants in arts and craft report sadness over the fact that they cannot reward their students for high participation alone due to government grading regulations. Participation appears to be a persistent element of teachers’ own considerations of grading practices across all school subjects, although some subjects are more adaptable to these concerns than others, due either to a long-standing structure (mathematics) or commitment to a certain practice (arts and craft).

Mismatch of epistemologies and validity of grades

This study reveals a tension between the school subject as a construct for grading and universal system (national regulations) for grading constructs. Previous studies have found similar results and suggested that controversy can occur when there is a mismatch between the theories and epistemologies that drives the instructional activities and assessment processes (Eggen Citation2004:480, Brookhart Citation1994, Stiggins et al. Citation1989, Airasian & Jones Citation1993). In this study this becomes evident when grades are aggregated at the system level and comparisons are made between grades in mathematics (informants report that they always use all six grades) and Norwegian (informants report that they never use grade 1 and seldom use grade 6); this clearly compromises comparability. Comparability is also compromised when grades are assigned in a variable manner for different subjects and different groups of students, either based on performance alone or on performance in combination with participation. The findings indicate that the different epistemological cultures of different subjects may lead to variability in the validity and reliability of teachers’ assessments. And it indicates weakness in the validity (and reliability) of grades where they are used as national indicators for learning outcomes and international benchmarking.

Conclusion and implication for policy

This study aimed at investigating three research questions: How do teachers approach grading in different school subjects? How do grading practices in different subjects correspond to the recommendations and regulations for grading at system level and what are the implications for the validity of indicators of learning outcomes based on students’ grades?

The findings show that the distinctive characteristics of the various school subjects do matter when it comes to the evidence used, the tools employed and the elements of student behaviour emphasised by teachers when grading. The study also suggests that different subjects involve different challenges, and even obstacles, in fulfilling government recommendations and regulations for grading. Some subjects appear to be easily adaptable to an outcomes-based educational system, while others have a long way to go to fulfil government recommendations and regulations. The findings underline the definitional role that school subjects have in educational processes, and the need to consider subject differences in discussions on grading.

Different contexts, like those of formulation (the educational policy context) and of realisation (educational practice), are characterised as being inconsistent due to differences in the conditions for realising and formulating educational policy (Skedsmo Citation2011:17). Further, it has been pointed out that policy-makers often avoid choosing between various value positions involved in educational change; by embracing contradictory concepts such as common standards and individual variation, numerical comparability and descriptive sensitivity, improving individual student learning and complying with requirements of system-wide accountability, policy-makers leave the job of resolving these contradictions to teachers (Hargreaves et al. Citation2002:84). Another issue raised by these findings is the de-contextualisation of schooling into discrete units of schools, teachers, students, parents, school districts and so on: this makes it easier for both researchers and policy-makers to treat these as separate, closed worlds. At the same time, this runs the risk of neglecting the context of schooling which gives meaning for those participating in the events of schools and classrooms, going beyond the official institutional boundaries of schools (Nespor Citation2002:376). This investigation indicates that the teachers have a strong relationship to their context in terms of a historical dimension (practice within new and old regulation of grading), through their commitment to their particular subject and through their professional values about fairness in grading. Indeed, these contextual commitments may be stronger for many teachers than their commitment to the official regulations for grading. Changing an established tradition of final grading determined by teachers, through the implementation of new national, system-wide regulations with the aim of applying to grading practice in all subjects, seems to be an overly optimistic project, at least in the short-term. The multidimensional purposes and uses of final grades found in the Norwegian case illustrate how inconsistencies between policy and practice, contradictions in policy and the decontextualisation of schooling can create challenges to the ideas of national and international benchmarking and the use of indicators of learning outcomes, such as final grades assigned by teachers.

One policy implication of this study is to underline the importance of school subjects in relation to teachers’ grading practices. The study also serves as a warning against underestimating the contextual dimensions in teachers’ grading practices when implementing policy changes, and stresses that it will be vital to recognise differences related to school subjects in ongoing efforts to extend and increase the measurement of students’ learning outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Jorunn Møller, Petter Aasen, Jorunn S. Borgen, Berit Karseth and Rachel Sweetman for their valuable comments on an earlier draft of this article.

Notes

Tine S. Prøitz is a researcher at NIFU (Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education) and a PhD candidate at the University of Oslo in Norway. Her professional interests cover studies of learning outcomes as a conceptual phenomenon at the intersection between education, quality and accountability and studies of educational reform.

1. The Knowledge Promotion reform in 2006 and the revision of the Norwegian educational act, particularly the chapter on assessment and final grading, which was amended in 2009.

2. The investigation is funded by the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. The background for the research project is the lack of empirically documented knowledge on how teachers assign final grades in Norway. This article is based on the data material and analysis presented in the project report (Prøitz and Borgen Citation2010).

3. In Norway there is a system of national examination with nationally developed exams and external examiners that is thought to provide a way of calibrating teachers’ grading practices. However, the system covers only a limited number of core subjects, including Norwegian and mathematics.

4. Very few grade-level effects of relevance for this study were identified; therefore, this issue will not be discussed further in this article.

5. The Act of 17 July 1998 no. 61, relating to Primary and Secondary Education and Training (the Education Act), amended 2010.

6. Here the informants are referring to the most recent revision of the Act of 17 July 1998 no. 61 relating to Primary and Secondary Education and Training (the Education Act), amended in 2010, which emphasises that final grades are to be based solely on performance and knowledge. Before this, teachers were also expected to take student effort, attitude and participation into consideration when grading.

References

- Allen J. Grades as Valid Measures. Clearing House. 2005; 78(5): 218–223.

- Airasian P.W, Jones A.M. The Teacher as Applied Measurer: Realities of Classroom Measurement and Assessment. Applied Measurement in Education. 1993; 6(3): 241–254.

- Brookhart S.M. Teachers’ Grading: Practice and Theory. Applied Measurement in Education. 1994; 7(4): 279–301.

- Brookhart S.M. Letter: Grading Practices and Validity. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 1991; 10(1): 35–36.

- Brookhart S.M. Teachers’ Grading Practices: Meanings and Values. Journal of Educational Measurement. 1993; 30(2): 123–142.

- Brookhart S.M. Developing Measurement Theory for Classroom Assessment Purposes and Uses. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 2005; 22(4): 5–12.

- Black P, Harrison C, Lee C.S, Marshall B, Wiliam D. Assessment for learning, putting it into practice. 2003; Open University Press.

- Duncan C.R, Noonan B. Factors Affecting Teachers’ Grading and Assessment Practices. The Alberta Journal of Educational Research. 2007; 53(1): 1–21.

- Engelsen K.S, Smith K. Is ‘Excellent’ good enough?. Education Inquiry. 2010; 1(4): 415–431.

- Eggen A.E. Alfa and Omega in Student Assessment; Exploring Identities of Secondary School Science Teachers. 2004; Department of Teacher Education and School Research, University of Oslo. PhD thesis.

- Hargreaves A, Earl L, Schmidt M. Perspectives on Alternative Assessment Reform. American Educational Research Journal. 2002; 39(1): 69–95.

- Harlen W. Teachers’ Summative Practices and Assessment for Learning – Tensions and Synergies. The Curriculum Journal. 2005; 16(2): 207–223.

- Hertzberg F. Assessment of writing in Norway: A case of balancing dilemmas. Balancing Dilemmas in Assessment and Learning in Contemporary Education. 2008; RoutledgeFalmer. 51–60. Havnes A. & L. McDowell (eds.),.

- Karseth B, Sivesind K. Conceptualising Curriculum Knowledge Within and Beyond the National Context. European Journal of Education. 2010; 45(1): 103–120.

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. InterViews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Los Angeles: SAGE. 2009; 2nd edition,

- Lawn M. Governing through Data in English Education. Education Inquiry. 2011; 2(2): 277–288.

- Lekholm A.K, Cliffordsson C. Effects of Student Characteristics on Grades in Compulsory School. Educational Research and Evaluation. 2009; 15(1): 1–23.

- Lekholm A.K, Cliffordsson C. Discrepancies between School Grades and Test Scores at Individual and School Level: Effects of Gender and Family Background. Educational Research and Evaluation. 2008; 14(2): 181–199.

- Lundahl C. Viljan att veta vad andra vet. 2006. Avhandling Uppsala Universitet. Arbetsliv i omvandling 2006:8. Arbetslivsinstituttet. Sverige.

- Lysne A. Assessment Theory and Practice of Students’ Outcomes in the Nordic Countries. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. 2006; 50(3): 327–359.

- McMillan J.H. Understanding and Improving Teachers’ Classroom Assessment Decision-Making: Implications for Theory and Practice. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 2003; 22(4): 34–43.

- Melograno V.J. Grading and Report Cards for Standards-Based Physical Education. Journal of Physical Education. Recreation and Dance. 2007; 78(6): 45–53.

- Messick S. Validity of Psychological Assessment. Validation of Inferences from Persons’ Responses and Performances as Scientific Inquiry into Score Meaning. American Psychologist. 1995; 50(9): 741–749.

- Muller J. Forms of Knowledge and Curriculum Coherence. Journal of Education and Work. 2009; 22(4): 205–226.

- Nespor J. Networks and Contexts of Reform. Journal of Educational Change. 2002; 3(3–4): 365–382.

- Prøitz T.S, Borgen J.S. Rettferdig standpunktvurdering – det (u)muliges kunst?. 2010. NIFU STEP report 16/2010.

- Resh N. Justice in Grades Allocation: Teachers’ Perspective. Social Psychology of Education. 2009; 12(3): 315–325.

- Skedsmo G. Formulation and Realisation of Evaluation Policy: Inconsistencies and Problematic Issues. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability. 2011; 23(1): 5–20.

- Shepard L.A. The Role of Assessment in a Learning Culture. Educational Researcher. 2000; 29(7): 4–14.

- Skolverket. Nationella prov i gymnasieskolan – ett stöd för likvärdig betygsättning?. 2005. www.skolverket.seper november 2009 .

- Stiggins R.J, Conclin N.F. In teachers hands: Investigating the practices of classroom assessment. 1992; Albany: SUNY Press.

- Stiggins R.J, Frisbie D.A, Griswold P.A. Inside High School Grading Practices: Building a Research Agenda. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice. 1989; 8(2): 5–14.

- Telhaug A.O, Aasen P, Mediaas O.A. From Collectivism to Individualism? Education as Nation Building in a Scandinavian Perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. 2004; 48(2): 141–158.

- Tyack D, Tobin W. ‘Grammar’ of Schooling: Why Has It Been So Hard to Change?. American Educational Research Journal. 1994; 31(3): 453–479.

- Wiliam D. National Curriculum Assessments and Programmes of Study: Validity and Impact. British Educational Research Journal. 1996; 22(1): 129–141.

- Yin R.K. Case study techniques: Design and method. 1994; (2nd ed.), Newbury Park, CA: Sage.