Abstract

Even though recurring criticism has been directed against the academic part of teacher education, little research has focused on student teachers as they engage in their academic studies. Reporting on a study of 53 Norwegian student teachers, this article explores student teachers’ reading practices in university courses in education. The study draws on the notion of approaches to learning as a particularly influential perspective in research on higher education. The findings reveal that the student teachers predominantly apply a deep approach to learning (with the aim to understand) and that writing academic texts in particular acts as an enabler of this approach. However, the participants also reported considerable difficulties with reading pedagogical literature. The article suggests that, in order to understand the persistent criticism against teacher education, there is a need to pay explicit attention to supporting student teachers in dealing with different text genres and texts from different academic disciplines. It also suggests that the important factor in students’ engagement with theory is not necessarily that it can be used immediately in the classroom, but that they recognise themselves as persons. Finally, the article raises a question about the balance between breadth and depth in the university courses.

Introduction

“The form you guys use in your articles gets in the way of the content!”. This comment about pedagogical literature was made when I was teaching a group of student teachers in a Postgraduate Certificate in Education course. Two things about that brief comment caught my attention. First, the way the student said “you guys” – with me being one of them – indicated that he did not consider himself as part of the same community. Second, it once again confirmed my impression that many of our students experience difficulties with reading pedagogical literature, and that they tend to have little confidence in the authors.

Through the decades, the academic part of teacher education has been the target of criticism from fresh graduates, school administrators, politicians and researchers alike. The main criticism relates to the academic part of teacher education: that teacher education is overly theoretical and distant from practice. Research repeatedly shows that student teachers struggle with contradictory realities of teaching and learning (Britzman Citation2003). At the same time, particularly in the Scandinavian countries, teacher education has increasingly become an academic discipline. It is widely believed that teachers need a sound theoretical base in education as well as in subject disciplines (Floden and Meniketti Citation2005) – a belief that seems to be shared by Norwegian student teachers (Roness Citation2011, Sjølie Citation2014).

Although the criticism has been directed against the academic part of studies, little research has focused on student teachers as learners in higher education, i.e. how they work with their academic studies and the challenges they encounter. Research on student teachers’ learning in university courses has been dominated by small-scale studies on innovative teaching methods (see the review by Cochran-Smith and Zeichner Citation2005). Further, research on teacher education has been largely isolated from research on student learning in higher education (Grossman and McDonald Citation2008).

The focus of this article is on student teachers’ reading practices in terms of support and challenges. The study is set in a Norwegian secondary teacher education programme and draws upon perspectives from student learning in higher education as well as research on genre effects on higher education students. The study aims to understand the student teacher perspective

Reading in higher education

A particularly influential perspective in research on student learning in higher education is the notion of approaches to learning. The main concern within this line of research is how to design teaching and learning environments that encourage ‘good learning behaviour’. ‘Good learning behaviour’ is mainly associated with a deep approach to learning as opposed to a surface approach to learning – a distinction that originates from Marton and Säljö's (Citation1997, Citation1976) research in Sweden in the 1970s.

Approaches to learning are usually described as being guided by the student's intention, characterised by certain learning strategies, and also reflecting a particular kind of motivation. A deep approach is seen as guided by intrinsic motivation and the intention to understand ideas and seek meaning. Using this approach, students adopt strategies that include relating ideas, looking for patterns and underlying principles, and seeing tasks as making up a whole (Prosser and Trigwell Citation1999). A surface approach, on the other hand, is guided by extrinsic motivation and the intention to meet the course requirements with minimum effort (Entwistle and Peterson Citation2004). The strategies applied are directed towards memorising facts and carrying out procedures. Some researchers (see Tait et al. Citation1998) also operate with a third approach, a strategic approach. A strategic approach includes the influence assessment has on students’ studying, and the intention to do as well as possible in a course. It is more an approach to studying rather than learning as it involves the ability to switch between deep and surface approaches (Volet and Chalmers Citation1992).

Through extensive research over the last 30–40 years it has been empirically established that a deep approach leads to high learning outcomes and a surface approach to poor ones (see, e.g., Diseth and Martinsen Citation2003; Diseth Citation2007; Kember and Leung Citation1998; Lizzio et al. Citation2002; Pettersen Citation2010; Prosser and Trigwell Citation1999; Richardson Citation2000; Trigwell and Prosser Citation1991). While the original studies by Marton and Säljö focused solely on reading, the notion of deep and surface approaches to learning now comprises a larger framework that includes a broad range of concepts describing learning and teaching in higher education (see Biggs and Tang Citation2011; Entwistle, Citation2009; Prosser and Trigwell Citation1999; Richardson Citation2011).

Studies on reading that build upon the original research by Marton and Säljö have shown that a deep approach might be a necessary but not a sufficient condition for understanding a text (Marton et al. Citation1992; Marton and Wenestam Citation1988). Following this line, Francis and Hallam (Citation2000) explored how students studying for higher degrees in education understood different text types. They found that the ability to deal with text genre is another necessary condition for thorough understanding. The students in their studies attributed difficulties with reading to aspects of the style, organisation and language of the text. A frequently reported effect was to skip or ignore texts that at first sight appeared to be difficult to understand. The authors also reported that, rather than considering the idea that texts can be written in different ways for different purposes, the students simply blamed authors for poor and unclear writing (Francis and Hallam Citation2000). Their studies imply that prior experiences (also within the academy) may not be suitable for new texts or new courses. They stress that it is important that awareness of genre be cultivated in relation to the texts used within the very practices of learning and teaching (Francis and Hallam Citation2000; Hallam and Francis Citation1998). Their studies also imply that switching between different academic disciplines – involving different text genres – should be paid particular attention.

Subject discipline as an important contextual factor is also emphasised within the approaches to learning literature. An array of studies indicates that the academic discipline has a direct effect on how students approach learning (Eklund-Myrskog Citation1996; Lawless and Richardson Citation2004; Sadlo and Richardson Citation2003; Vermunt Citation2005). The different nature of subject disciplines involves different processes that are involved in deep learning (Entwistle Citation2009). Lawless and Richardson (Citation2004) explained this as well-established “house-styles”, which arrange for and reward certain orientations or approaches. There has, however, been little attention to the fact that students need to switch between these different house-styles and that there are differences not only between different disciplines but also within courses and modules (Lea and Street, Citation2000). Student teachers in particular must navigate among different academic disciplines – between different school subjects as well as between the school subjects and educational studies. Further, literature in education draws upon different traditions such as psychology, philosophy, sociology and history, which means the students are expected to deal with many different text genres in their coursework.

Meaning and relevance

The main aspect of a deep approach to learning is the focus on ‘meaning’. A deep approach is defined as including a search for personal meaning based on intrinsic interest, curiosity and a desire and ability to relate learning to personal experience (Prosser and Trigwell Citation1999). Haggis (Citation2003) notes that ‘meaning’ is an extremely general term that can be interpreted in a variety of ways. Often, meaning is interpreted as finding the ‘correct’ connections, exemplified by Marton and Saljö (Citation1997, 43) when they refer to students “who did not get the point” and McLean (Citation2001) who notes that “a meaningful experience is thus likely to arise only once a student has been able to grasp the principles”. Although the literature largely argues for a constructivist view of learning, in which the students construct their own point of view and develop a critical disposition, there are nonetheless some correct answers. On the other hand, it is perfectly permissible to criticise authority as long as the criticism is well argued and done in a correct way. Laurillard (Citation2002) points to the paradox that “we want all our students to learn the same thing, yet we want each to make it their own”. This understanding of meaning is highly constrained by disciplinary boundaries, cultural norms and assessment mechanisms (Haggis Citation2003).

The search for meaning is a general characteristic of human beings, which means that personal meaning can be tied up with many aspects of life that are not directly connected to studying. Perhaps studying is only a small part of whatever meaningful activities a person is engaged in (Haggis Citation2003). In teacher education, the debate revolves considerably around ‘relevance’. Claiming that something is ‘irrelevant’ is akin to saying that it does not feel meaningful. Based on the persisting criticism that much of what is taught in teacher education is irrelevant, the topic of relevance and meaning will be a particular focus when analysing the students’ stories about their reading.

The study

The data for this study have been collected from a whole-year cohort of 53 student teachers from a five-year secondary teacher education programme in Norway. In this programme, the students are provided with teacher education combined with a Master's degree in one academic subject as well as one year's study in a secondary subject. The academic subjects are studied within the ordinary Bachelor or Master's programmes of each academic discipline, while two terms – the fifth and the eighthFootnote1 – are dedicated in full to coursework in education.

The main assessment form in this programme is a portfolio, and the students are assessed in three different courses: pedagogy and subject didactics Footnote2 in two different (and separately assessed) school subjects. The portfolio consists of written assignments in which the students are expected to reflect upon practical experiences or educational issues in light of theoretical perspectives from their university courses. The portfolio also includes an R&D project in which the students do research on their own practices. In addition to the portfolio, the students have a written test in each of the subjects after the fifth term of the programme. Due to changes being made in the assessment form in this particular year, half the participants also had an oral exam in pedagogy, while the other half only had the portfolio. The data were collected at the end of the eighth term, just before they were about to finish their exams. The research question that has guided the analysis is: How do student teachers describe their reading practices?

Data collection and analysis

The main data comprise six focus group interviews with 18 student teachers (three in each focus group). Focus groups were selected to better stimulate discussion. Kitzinger (Citation1995) notes that the interaction between participants in a focus group highlights their view of the world, the language they use about various topics and their values and beliefs about particular situations. Group processes can help people discover and elucidate their views in ways that cannot be done in individual interviews. Through sharing views and experiences and asking each other questions in the group, forgotten nuances may be activated and understandings can be re-evaluated and reconsidered (Catterall and Maclaran Citation1997).

The selection process was based on an open invitation, and a mix of subject disciplines was secured.Footnote3 The interviews, which each lasted between 90 and 120 minutes, were semi-structured with open-ended questions to facilitate group discussion. The interviews covered different aspects of the student teachers’ learning practices, including questions about experiences from the practicum and questions about being a university student. The transcripts were analysed in full, but the findings presented in this article are predominantly from those parts where the students were asked about their reading and writing practices. The questions focused particularly on reading, and two specific texts from the students’ reading list were used as the background for an opening question. The students talked about how they usually go with respect to reading and writing assignments as well as relating this to their overall experiences with their academic studies.

In addition to the focus groups, the whole-year cohort was asked to fill out a questionnaire. The questionnaire combined the Approaches and Study Skills Inventory for Students (ASSIST) (Tait et al. Citation1998) and the Course Evaluation Questionnaire (CEQ) (Ramsden Citation1991). Both of these inventories have been translated and validated in a Norwegian context (Diseth Citation2001; Pettersen, Citation2007). To secure a high participation rate, an agreement with the teachers of the pedagogy course was made so that the questionnaire could be filled out during a workshop. I was present at all workshop groups to inform the students about the procedure (e.g. that participation was voluntary) and to be available for questions. Due to absences on that particular day, 53 out of the whole-year cohort of 59 students completed the questionnaire. The questionnaire was filled out before the focus groups so that I could identify possible topics to investigate in more depth during the conversations.

The questionnaire

The intended use of the questionnaire was to use descriptive analysis to describe the study approaches of this particular group and also to analyse possible relationships between these approaches and contextual factors such as perceived quality of teaching and conceptions of learning. However, the theoretical underpinnings of the questionnaire turned out to be difficult to reproduce. A factor analysis only reproduced two of the main factors: deep and strategic approaches to learning. It was not possible to demonstrate a surface approach to learning by using the ASSIST items.Footnote4 One explanation for the lack of any clear surface approach can probably be found in the fact that the assessment form (portfolio) did not ask for facts or reproduction. A surface approach might therefore not be present among these students. Further, factor analysis and validity tests indicated that the questions relating to the surface approach might not have made much sense to the students and therefore might have been interpreted in different ways. For example, the statement “Much of what I'm studying makes little sense: it's like unrelated bits and pieces” can also apply to students who have a deep approach to learning. As will be discussed in the findings section, the students reported considerable problems in dealing with the language in pedagogical literature. They might want to understand and to search for meaning, but are unable to find it. The data sample is not large enough to go into a deeper analysis of the reliability of the instrument, and the results from the questionnaire therefore merely serve as a background for the discussion of the findings.

Descriptive statistics for the deep and strategic approaches are given in . As seen in the table, the students reported that they were predominantly oriented towards a deep approach, but also a strategic one (1=totally agree, 5=totally disagree). Of the 53 students, only three students had a mean value above 3 (the neutral value) for a deep approach.

Table 1. Descriptive analysis for the deep approach and the surface approach (1=totally agree, 3=unsure, 5=totally disagree). Sum scores for each subscale and approach were calculated and normalised.

Data analysis of the interviews

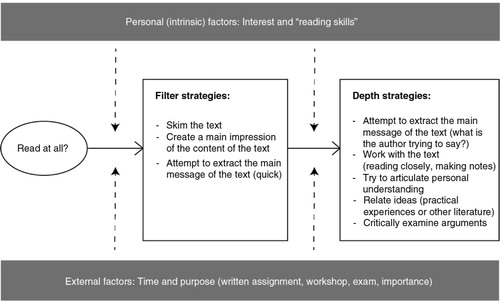

All interviews were conducted and transcribed verbatim by the author. The interviews were anonymised and imported into NVivo. Although the theoretical framework of approaches to learning informed parts of the data collection, the intention was to remain open to the student perspective. The analysis was therefore conducted using a conventional qualitative content analysis (Hsieh and Shannon Citation2005). In this kind of analysis, themes are identified directly from the text data without imposing preconceived theoretical perspectives. Initial (or open) coding, categorisation and abstraction (Saldaña Citation2009) were used to search for patterns within the data. Two main categories emerged from the analysis: filter and depth strategies for reading. These categories were then analysed in the context of approaches to learning.

Findings

In light of approaches to learning, the overall finding from the interviews is that the students are oriented towards meaning and understanding, which supports the findings from the questionnaire and the problems of reproducing the surface approach. The overall aim of the students is to understand the texts they read, and there were no signs of surface approaches in the students’ descriptions of their reading. The spontaneous answers about their reading practices were, however, related to the question of whether the students should bother to read the text at all. The findings indicate strategic behaviour that seemed to be guided by various factors. Due to this strategic behaviour, I have labelled the students’ reading behaviour as strategies.

Two main groups of reading strategies were identified: filter and depth strategies. Generally, filter strategies were applied first and then, depending on the situation, depth strategies were applied or not applied. In other words, all participants used a combination of filter and depth strategies, but depth strategies were only applied to selected texts. Filter strategies can be interpreted as a strategic approach as the students used filter strategies to decide if they should bother to read the text more in depth or not. However, it can be better understood as a combination of a search for meaning and pragmatic (or strategic) consideration. The depth strategies have much in common with a deep approach. How the students worked with texts was influenced by personal or intrinsic factors as well as external or contextual factors of the programme. In the following, the influence of these factors will be presented in detail. shows an overview of influencing factors and strategies that emerged as patterns from the students’ statements.

External factors

Every time I read it is for a particular purpose, whether this is going to be tested in the exam, or it is needed for writing an assignment or that it is simply important for me now. There is so much of the syllabus that I have not read at all that probably would have been very interesting. (Fanny)

Fanny sums up very well the essence of what the students say about their reading. They were guided by time since time limited how much they were able to read, and forced them to prioritise and make pragmatic choices to cope with the here and now. The perceived workload of these students was generally very high (CitationSjølie and Østern, forthcoming). Rather than taking a surface approach, which is the approach associated with a high workload in the literature, Fanny illustrates how she chose to read only parts of the syllabus (the first stage in ).

In addition to time, three other factors were identified as influencing the choice of applying depth strategies or not: written assignments, preparation for workshops, and exams or reading lists.

Written assignments

Written assignments were undoubtedly the most decisive factor for the students to work with the text in a ‘deep’ way. When reading with a particular assignment in mind, they reported working with the text in greater depth; they claimed to seek to understand, to critically examine arguments, to relate with other ideas (practical experiences or literature), to create their own understanding, and they wanted to be able to use the theory independently. These aspects can also be recognised from the ASSIST questionnaire under a deep approach to learning. Below is an extract of the data material that illustrates the effect of having to write an assignment:

The only time I read difficult texts that are relevant is when I know I need it for something, whether it is for an assignment or if I'm going to be assessed on it in some way. I had this article … I had to read it for the assignment in mathematics didactics. It had this model in it, which is very complicated. But I liked it and I kind of saw that it could be used. So I had to force myself through this heavy academic text and understand it. I think I spent a whole day trying to understand what was in that article. The article was only six pages or something, but I kind of had to force myself through it because I wanted to use it. If it hadn't been for that, I would just have skimmed through it. (Ben)

It was the combination of reading and writing that was seen as most meaningful to the students. Having a topic in mind made it easier to focus their reading, and writing about the topic helped them use what they had read and formulate their understanding. However, there was an interesting shift of perspective when they changed from talking primarily about reading to talking primarily about writing assignments for the portfolio. When they talked about their reading, the focus was chiefly on understanding and the search for meaning, and writing was almost without exception described as an enabler for achieving a thorough understanding of the topic. When they switched to talking about writing, the focus was primarily on assessment (to show what they had learned) and on the difficulties they had encountered when trying to learn how to write academic texts.

The students mainly reported that it was difficult to understand what characterises a good text, especially because this seemed to be different between the courses, depending on the teacher. It could apply both to the structure and content of the text, but also to the ‘style of writing’. Some said writing became more a matter of learning the ‘academic game’ than about demonstrating understanding. One example is Kenneth:

I get the feeling that it does not test my ability to use the literature as much as my ability to cram in names. So … namedropping, and then I kind of like blaaah […] Yeah, I made duplicate references. You want more references, I'll give you some. It's not difficult, I'll just use the theoretical material. (Kenneth)

Preparation for workshops

The second factor with the potential of influencing the students’ reading practice in a positive way was pre-readings for workshops. When reading was part of the preparation for workshops, the students reported they did not read in depth as much as they did when they were working with written assignments; all the same, their aim was to understand the main message of the texts. The discussions in the workshops helped them process and work with the text afterwards. The students generally described these workshops as very worthwhile and as an enabler for their understanding of the texts since they could discuss the texts in relation to cases or personal experiences. The condition for such an effect seemed, however, to be closely connected to how the workshops were organised, which is illustrated by the following quote:

In the pedagogy workshops, there tends to be a clear connection between what we should read and what we use. Gradually, many people have started to read in advance because it is actually expected that we discuss what we have read. While in mathematics and physics didactics I feel we are given pre-readings in order to have a backdrop for what is covered in the lessons. It doesn't feel so useful, especially when you don't get anything out of an article of 20-30-40 pages. (Oliver)

Oliver points here to the fact that the students needed to experience the advantage of reading in advance. They experienced that they were able (and expected) to contribute actively in the workshops, and through discussions with peers improve their understanding of the topic in question. A general comment across all interviews was that despite the ‘reading plan’ that provided an overview of how different texts from the reading list fit into the teaching plan of the whole term, the students soon realised that they did not really have to read in advance. When the lecturers were able to add something to their understanding of the texts, many of the students claimed they would read in advance. But they first needed to see how reading and teaching were connected to each other. Oliver's quote also indicates difficulties with reading, which will be commented on in more detail under intrinsic factors.

Exams or reading lists

Factors that did not enable reading (i.e., depth strategies were not applied) were when the students were reading for a testFootnote5 or because it was on the reading list for the course. As one student said when commenting on these tests, the focus shifted from understanding to: “what do they want to hear from this?”. Other students called it the “typical university thing – rote learning” or that “it felt entirely meaningless”. These negative comments also signal that the students were predominantly oriented to understanding, as they were dissatisfied with structures that “forced” them to be otherwise. Some students had an original aim of reading all the literature in the course (and a few also did), but a lack of focus (which included reading for tests) and purpose made it difficult:

Fanny: We need some kind of focus when we read, but we often don't have that. You don't really know what you're supposed to use it for, but you must learn it.

Cecilie: Yeah, that's often how it is at university. When we read, we just read for reading's sake.

In general, reading had to feel useful and they had to feel that they ‘get something out of it’. However, this feeling of usefulness, which in turn influenced their strategies, was also guided by personal or intrinsic factors.

Intrinsic factors

The quote below captures the two topics that can be related to intrinsic factors: interest and reading skills:

The articles are about 20 pages each and it's pretty heavy stuff. A number of authors write for a higher audience than students, although some claim that it is written for students. And then it's a bit like … what I feel is useful and good with an article or chapter is that I become a bit interested when I start reading it. I notice the difference for example between Skemp and Yong, they're like two different worlds. Skemp is talking about something that I can relate to, he talks to me in a language that I understand, and he uses examples from everyday life. Also, he's talking about my future life as a teacher. While Yong – fair enough it's in English but that's not a problem for me – I had to read a paragraph two or three or four times before I got it, that means: how would I say this sentence in Norwegian to another person? I kind of understood what he said, but how can I translate this really? That's when you begin to realise how complicated he actually writes. It's funny, some of the articles that I have read in this term, it's like … I want to finish the article, but …. And that's how it often is when we are given pre-readings of like 20 pages each. (Kenneth)

Reading skills

Reading skills refers to how the students regarded their own skills in reading the discipline-specific literature of pedagogical texts.Footnote6 Some students labelled themselves as “poor readers” of pedagogical literature, but a more common complaint concerned the language and form (cf. the quote at the very beginning of this article). The students found the language in much of the literature unfamiliar and difficult, “unnecessarily complicated”, sometimes “just a torrent of words”, and many of the interviewees concluded that pedagogical literature is largely common-sense written in a difficult language. The problematic encounter with pedagogy as an academic discipline is discussed in more detail in two other articles reporting on the same study (Sjølie Citation2014; Sjølie and Østern forthcoming). In line with Francis and Hallam (Citation2000), the students blamed the authors for poor writing. As a result, unless they were “forced” through it, they gave up or just did not bother trying at all.

Interest

While strongly guided by external requirements, the students’ reading was also guided by an intrinsic interest and motivation. If the text was interesting, they would read it even though they did not really have to. “Interest” is often used synonymously with “relevance” and, because teacher education is often criticised for being irrelevant, I was particularly interested in exploring how the students described relevance. What makes something relevant?

In the interviews, this topic required several levels of questioning from me as a researcher. The first, spontaneous answers about relevance were that what they read needed to be useful in the short term. In addition to written assignments and workshops, this could be that they were able to see the immediate relevance for their classroom practice. When elaborating further, they also referred to topics that could be related to the teaching profession in a broader sense and in a long-term perspective. As two of the students said: “I read as a teacher. Everything that is connected to my future as a teacher is relevant”. Considering that all topics that are included in these courses are related to the teaching profession in a short- or long-term perspective, there is obviously more to the feeling of interest and relevance. This was, however, not easily put into words. Many students described it through a general feeling of something being “exciting” or “engaging” and that “you just want to go on reading and learn more”. They used expressions like “it struck a chord” or “I get that good feeling when I read it”. The topics that were brought up as positive examples covered a wide range and were mainly linked to the topics of their written assignments: from specific teaching methods and texts related to the teacher as a person to bullying, the history of education and the school's responsibility in society. These were topics the students had chosen to write about based on their own interest. The students were then asked to explain what it was with these specific texts that had made them interesting to read.

When the students characterised interesting texts, they revealed two main categories of the source of that interest: recognition and transformation. The above quote from Kenneth contains several of the ways the students described the importance of recognition. Kenneth describes it as the feeling that the author is talking to him and that he uses examples that he can relate to and connect to personal experiences. Depending on the topic of the text, some students said that texts did not make much sense until after the students had been in the practicum. This is what Tessa refers to below when she talks about a text about guilt:

It was much easier for me to understand it after I had been in the practicum and seen it. ‘Yes, this is exactly how it is’, and he uses very many concrete examples of situations, he has certainly done plenty of research, and... I thought: ‘oh my gosh, I've seen this in the school I was placed in’. And what he writes about guilt and emotions in teaching, I could really identify with it. (Tessa)

The most common explanation within this category was that a text became interesting when it confirmed and supported their experiences.

When interest was described as being transformative, it was not only recognition but also an expansion or bringing in new perspectives. There were only a few examples of this in the data. One student described it as an experience of seeing the bigger picture of her teaching practice from a societal level – things she had not thought of before. Others said that the text was an “eye opener”, that it “triggered some thoughts” or “challenged me to think”. Below is an example of an “eye opener”:

Suddenly … there was something … my understanding of learning was kind of …. it was extended. I understood more of how I understand things, and how others around me understand things. And I realised why there is a difference … that I understand maths in a different way than others understand maths. Why do people have trouble understanding maths for example. I got that one! (Ben)

Above all, interest seemed to be triggered by reading in depth about a particular topic. The literature they referred to as interesting and relevant was mainly literature they had been reading on a topic they had studied in depth. The participants said that when they had an assignment to focus on they read many texts that were not on the reading list. This, in turn, made reading more interesting. Some described that it made them see connections, experience coherence, and understand a topic more thoroughly.

Discussion

This report of a group of student teachers holds significance for both student learning in higher education in general and teacher education in particular. For higher education, the significance of this study is related to an approaches to learning perspective, which has become the canon for educational development across various disciplines (Webb Citation1997). The students’ descriptions of their reading practices within this teacher education programme draw a picture of a programme in which a surface approach is not stimulated (or present at all). Based on the findings from both the questionnaire and the interviews, the students in this study are predominantly intrinsically motivated and meaning-oriented; they read for understanding or not at all. On the other hand, they were also highly strategic. They described writing as enabling for reading, but the main motivation for reading in the first place was having to write an assignment for assessment. In the perspective of approaches to learning, the assessment form of the portfolio as well as the active use of pre-readings for workshops can be seen as contextual factors that stimulated the application of depth strategies (cf. Entwistle and Peterson Citation2004). The strategic behaviour can be understood in the light of time management. Other studies have found that an overload of curriculum can enforce a strategic approach to learning (e.g., Diseth and Martinsen Citation2003).

Yet the findings hold further implications. First, the findings seem to support the claim that an intention to understand a text (with a deep approach) is not a sufficient condition for understanding. Although this study did not focus on the students’ actual understanding of different texts, they reported considerable difficulties with reading. Similar to Francis and Hallam's studies (Francis and Hallam Citation2000; Hallam and Francis Citation1998), many of the students seemed to be ‘put off’ by the reading already before they had begun. They blamed the authors for poor writing, but also themselves for being incompetent readers. As the student quoted at the start of this article said: the form gets in the way of the content. For teacher education, these findings should be understood in relation to the critique that teacher education is overly theoretical. While one possible explanation could be an inappropriate selection of course readings, another explanation could be lack of attention to the challenges students experience when having to deal with highly different text genres and ‘house styles’.

An additional dimension this study adds is the feeling of relevance, which can be understood as the search for personal meaning. If the text was not perceived to be relevant (a decision that included the ability to deal with the language of the text), it was not read, even though reading it was expected as part of the course. The “search for personal meaning, intrinsic interest and curiosity” (cf. Prosser and Trigwell Citation1999) was not surprisingly directed towards becoming a teacher rather than the academic interest of learning a new discipline. What turned out to be meaningful was, however, highly individual. Contrary to the claim that is often made about student teachers being merely directed towards acquiring a set of professional skills (e.g., Loughran Citation2006), this study indicates otherwise. In asking the students to describe “relevance” rather than “irrelevance”, the students could identify highly meaningful experiences in their encounter with academic texts of various topics. While the importance of perceived relevance might be particularly important in professional education, it also points to a more general aspect of learning. As argued by Haggis (Citation2003), personal meaning may be tied up with many aspects of life that are not directly connected to studying. This is not often discussed in research literature, where ‘meaning’ is commonly used as finding the ‘correct’ connections in terms of the subject area.

A third implication relates to workload. The students reported to have mainly read for written assignments because of time pressure, reading difficulties, and interest. On the other hand, reading in depth about a topic made reading more interesting, in turn stimulating further reading, interest and learning about the specific topic. Perceived relevance and thus personal meaning seemed to be nurtured by reading and writing in a ‘virtuous cycle’ that allowed time for reflection. This directs attention to the workload and the relationship in a curriculum between breadth and depth. A perceived high workload and overloaded curriculum are a general concern in higher education (e.g., Kember and Leung Citation1998) and in teacher education in particular (e.g., Niemi Citation2002). In this study, a perceived high workload did not seem to produce a surface approach, but the students were instead highly selective in what they chose to read. This can be explained by the use of the form of assessment that made such a selection possible. A common counterargument when discussing workload in higher education is to use student diaries or student questionnaires to show that the time students spend on their studies is not more than is reasonable to expect (e.g., Kember et al. Citation1995). However, as also stressed by Francis and Hallam (Citation2000), the time spent on studies tells us little about the quality of the study and the work needed to understand texts is often underestimated. As pointed out by the students in this study, many had the feeling that the written assignments were often more a matter of learning the game of academic style than demonstrating understanding. In turn, this might shift the focus from seeking further understanding to applying the rules that are needed to get through the assignment.

Concluding remarks

Seeing the findings as a whole, this study suggests the need for closer attention to student teachers’ reading practices. It has also demonstrated that research on student learning in higher education also provides a valuable insight for teacher education. Above all, it suggests that there might be alternative explanations to student teachers’ criticism of an overly theoretical and irrelevant teacher education – a criticism that is largely taken as a given background for research. To summarise, the article pointed to three aspects of student teachers’ academic learning. First, it emphasised the need for explicit attention to support student teachers in dealing with different text genres and texts from different academic disciplines. Second, it suggested that the important factor in students’ engagement with theory is not necessarily that it can be used immediately in the classroom, but that they recognise themselves as persons. Further research is needed to explore how readings can be selected to achieve both recognition and transformation. Transformation in this context means to broaden the students’ understanding, which involves seeing more than what confirms and supports existing views. Third, the article raised the question about the balance between breadth and depth, and how to make time available for reading for understanding. Perhaps, in some ways, less is more.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ela Sjølie

Ela Sjølie is an associate professor in the programme for Teacher Education, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 7491 Trondheim; e-mail: [email protected]; Her interests centre on the pedagogy of teacher education and on student teachers’ learning.

Notes

1. Each year has two terms. Hence, it is the first part of the third year, and the second part of the fourth year.

2. The concepts of pedagogy and didactic are not understood in the same way in the Anglo-Saxon tradition or Continental tradition (see, e.g., Ax and Ponte Citation2010; Gundem and Hopmann Citation1998). For the purpose of this article, pedagogy can be compared with foundations in education, while subject didactics can be compared with curriculum courses.

3. The participants belonged to either the science programme or the languages programme. In the science programme, the students studied mathematics and one science subject (chemistry, biology or physics), while in the language programme the students studied either two of the following languages: Norwegian, English, German, French, and Spanish, or one of those languages in combination with social science, geography or religion.

4. Reliability tests with Cronbach's α and exploratory factor analysis were performed.

5. After the fifth term, the students had three written tests/exams, one in each subject.

6. Refers to literature within teacher education.

References

- Ax J., Ponte P. Moral issues in educational praxis: a perspective from pedagogiek and didactiek as human sciences in continental Europe. Pedagogy, Culture & Society. (2010); 18: 29–42. [PubMedAbstract] [PubMedCentralFullText].

- Biggs J. B., Tang C. Teaching for quality learning at university: what the student does. 2011; Open University Press: Berkshire.

- Britzman D. P. Practice makes practice: a critical study of learning to teach. 2003; N.Y., State University of New York Press: Albany.

- Catterall M., Maclaran P. Focus group data and qualitative analysis programs: coding the moving picture as well as the snapshots. Sociological Research Online. 1997; 2: 53–61.

- Cochran-Smith M., Zeichner K. M. Studying teacher education: the report of the AERA Panel on research and teacher education. 2005; Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Diseth A. Validation of a Norwegian version of the Approaches and Study Skills Inventory for Students (ASSIST): application of structural equation modeling. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. 2001; 45: 381–395.

- Diseth A., Martinsen O. Approaches to learning, cognitive style, and motives as predictors of academic achievement. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology. 2003; 23: 195–207.

- Diseth Å Students’ evaluation of teaching, approaches to learning, and academic achievement. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. 2007; 51: 185–204.

- Eklund-myrskog G. Students’ ideas of learning. Conceptions, approaches and outcomes in different educational contexts. 1996; Åbo Academy University Press: Åbo.

- Entwistle N. Teaching for understanding at university: deep approaches and distinctive ways of thinking. 2009; Palgrave: Basingstoke.

- Entwistle N. J., Peterson E. R. Conceptions of learning and knowledge in higher education: relationships with study behaviour and influences of learning environments. International Journal of Educational Research. 2004; 41: 407–428.

- Floden R. E., Meniketti M. Research on the effects of coursework in the arts and sciences and in the foundations of education. Studying Teacher Education: The Report of the AERA Panel on Research and Teacher Education. 2005; Mahwah, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Francis H., Hallam S. Genre effects on higher education students’ text reading for understanding. Higher Education. 2000; 39: 279–296.

- Grossman P., Mcdonald M. Back to the future: directions for research in teaching and teacher education. American Educational Research Journal. 2008; 45: 184–205.

- Gundem B., Hopmann S. Didaktik and/or Curriculum - and international dialogue. 1998; Peter Lang: New York.

- Haggis T. Constructing images of ourselves? A critical investigation into ‘approaches to learning’ research in higher education. British Educational Research Journal. 2003; 29: 89–89.

- Hallam S., Francis H. Is my understanding yours? A study of higher education students’ reading for understanding and the effects of different texts. Learning and Instruction. 1998; 8: 83–95.

- Hsieh H.-F., Shannon S. E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research. 2005; 15: 1277–1288. [PubMed Abstract].

- Kember D., Jamieson Q., Pomfret M., Wong E. T. Learning approaches, study time and academic performance. Higher Education. 1995; 29: 329–343.

- Kember D., Leung D. Y. Influences upon students’ perceptions of workload. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology. 1998; 18: 293–307.

- Kitzinger J. Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal. 1995; 311: 299–302. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Laurillard D. Rethinking university teaching: a conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. 2002; Routledge/Falmer: London.

- Lawless C., Richardson J. 2004. Monitoring the experiences of graduates in distance education. Customer Services for Taylor & Francis Group Journals, 325 Chestnut Street, Suite 800, Philadelphia, PA 19106.

- Lea M. R., Street B. Lea M. R., Stierer B. Student writing and staff feedback in higher education: an academic literacies approach. Student Writing in Higher Education: New Contexts. 2000; Guildford: The Society. 32–46.

- Lizzio A., Wilson K., Simons R. University students’ perceptions of the learning environment and academic outcomes: implications for theory and practice. Studies in Higher Education. 2002; 27: 27–52.

- Loughran J. Developing a pedagogy of teacher education: understanding teaching and learning about teaching. 2006; London, Routledge.

- Marton F., Carlsson M. A., Halasz L. Differences in understanding and the use of reflective variation in reading. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 1992; 62: 1–16.

- Marton F., Hounsell D., Entwistle N. The experience of learning: implications for teaching and studying in higher education. 1997; Edinburgh, Scottish Academic Press.

- Marton F., Säljö R. On qualitative differences in learning: I – outcome and process. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 1976; 46: 4–11.

- Marton F., Säljö R. Marton F., Hounsell D, Entwistle N. Approaches to learning. The Experience of Learning: Implications for Teaching and Studying in Higher Education. 1997; Edinburgh: Scottish Academic Press. 39–58. (eds.), 2nd ed..

- Marton F., Wenestam C.-G, Gruneberg M., Morris P. E., Sykes R. N. Qualitative differences in retention when a text is read several times. Practical Aspects of Memory: Current Research and Issues. 1988; New York: Wiley. 633–643.

- Mclean M. Can we relate conceptions of learning to student academic achievement?. Teaching in Higher Education. 2001; 6: 399–413.

- Niemi H. Active learning: a cultural change needed in teacher education and schools. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2002; 18: 763–780.

- Pettersen R. C. Studenters opplevelse og evaluering av undervisning og læringsmiljø: Presentasjon av Course Experience Questionnaire (CEQ) – og validering av tre norske versjoner, Erfaringer med studiet (EMS) [Students’ experience and evaluation of teaching and learning environment: presentation of the Course Experience Questionnaire (CEQ) - and validation of three Norwegian versions (EMS). 2007; Halden: Høgskolen i Østfold.

- Pettersen R. C. Validation of approaches to studying inventories in a Norwegian context: in search of ‘quick-and-easy’ and short versions of the ASI. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. 2010; 54: 239–261.

- Prosser M., Trigwell K. Understanding learning and teaching. 1999; Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press: Buckingham.

- Ramsden P. A performance indicator of teaching quality in higher education: the Course Experience Questionnaire. Studies in Higher Education. 1991; 16: 129–150.

- Richardson J. T. Approaches to studying, conceptions of learning and learning styles in higher education. Learning and Individual Differences. 2011; 21: 288–293.

- Richardson J. T. E. Researching student learning: approaches to studying in campus-based and distance education. 2000; Society for Research into Higher Education: Buckingham.

- Roness D. Still motivated? The motivation for teaching during the second year in the profession. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2011; 27: 628–638.

- Sadlo G., Richardson J. T. E. Approaches to studying and perceptions of the academic environment in students following problem-based and subject-based curricula. Higher Education Research and Development. 2003; 22: 253–274.

- Saldaña J. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. 2009; Los Angeles, Sage.

- Sjølie E. The role of theory in teacher education - reconsidered from a student teacher perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies. 2014; 46: 729–750.

- Sjølie E., Østern A. L. Forthcoming. Student teachers’ learning within the practice architectures of teacher education.

- Tait H., Entwistle N., Mccune V, RUST C. ASSIST: A reconceptualisation of the Approaches to Studying Inventory. Improving Students as Learners. 1998; Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff & Learning Development. 262–271.

- Trigwell K., Prosser M. Improving the quality of student learning: the influence of learning context and student approaches to learning on learning outcomes. Higher Education. 1991; 22: 251–266.

- Vermunt J. D. Relations between student learning patterns and personal and contextual factors and academic performance. Higher Education: The International Journal of Higher Education and Educational Planning. 2005; 49: 205–234.

- Volet S. E., Chalmers D. Investigation of qualitative differences in university students’ learning goals, based on an unfolding model of stage development. British Journal of Educational Psychology. 1992; 62: 17–34.

- Webb G. Deconstructing deep and surface: towards a critique of phenomenography. Higher Education. 1997; 33: 195–212.