Abstract

Background: Dietary calcium intake is assumed important in the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. However, people in countries with a high calcium intake from commodities such as milk and milk products have a high incidence of hip fracture. The effect and influence of calcium intake in the prevention of osteoporotic fracture vary from different studies.

Objective: To investigate premorbid daily calcium intake in patients with low energy hip fractures during four consecutive years.

Design: In total 120 patients (mean age 78±8.5 (SD) years) were included between 2002 and 2005. The patients answered a structured food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) and interviews on patients’ daily calcium intake from food and supplements took place during a 6-month period before the fracture. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) was performed in a subgroup of 15 patients.

Results: The mean daily calcium intake from food and supplementation was 970±500 mg. However, 38% of patients had an intake below the recommended 800 mg/day. There was no significant relationship between calcium intake and age, gender, bone mineral density, serum calcium or albumin, type of fracture or body mass index. The mean free plasma calcium concentration was 2.3±0.1, i.e. within the reference limit. In 2005, 80% of the patients who underwent DEXA had manifest osteoporosis. There was a trend towards decreased calcium intake over the observation period, with a mean calcium intake below 800 mg/day in 2005.

Conclusion: Hip fracture patients had a mean calcium intake above the recommended daily intake, as assessed by a FFQ. However, more than one-third of patients had an intake below the recommended 800 mg/day. The intake appeared to decrease over the investigated years. The relationship between calcium intake and fracture susceptibility is complex.

Introduction

In recent years, there have been great advances in the field of prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. New drugs acting on the modelling and remodelling bone process have been introduced in the management of osteoporosis Citation1. In osteoporosis, bone mineral density (BMD) is decreased partly due to decreased osteoblast bone formation Citation2. The consequences of osteoporosis are well known with regard to the risk of fractures Citation3. In particular, hip fractures are a growing problem worldwide. Half of all women will eventually suffer from a fracture after the age of 50 Citation4. Men are also affected with a 25% fracture risk after the age of 50 Citation4. Therefore, osteoporosis prevention is of outmost importance. In order to maximize BMD, the focus is on pharmacological treatment, e.g. with bisphosphonates. To some extent, this focus has decreased the awareness of the importance of energy and nutrients, such as vitamin D and calcium. An adequate intake of these nutrients is also necessary to ensure optimal benefit from drugs Citation5. A deficiency of calcium intake in itself is considered a major risk factor for osteoporosis Citation6. Milk and cheese are primary sources of calcium and therefore might be expected to have an impact on osteoporotic bone loss and fracture risk Citation7. Many patients fail to consume the minimum recommended daily intake of calcium Citation8Citation9, which in Sweden is 800 mg according to the Nordic Nutrition Recommendation (NNR 2004) Citation10. However, the observed intake in descriptive studies varies between 400 and 1,500 mg. Low calcium intake causes secondary hyperparathyroidism as the calcium homeostasis in blood must be kept stable Citation11Citation12. This causes resorption of calcium from the bone with ensuing bone loss and an increased susceptibility to fractures. There is a lack of studies on calcium intake in patients with hip fractures. The aim of this study was to estimate the daily intake of calcium during four consecutive years in patients with hip fracture in relation to age, gender, biochemical markers of nutrition and BMD.

Material and methods

Elderly patients with a low energy hip fracture awaiting an operation were consecutively recruited from a gero-orthopaedic ward at the Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge, Sweden. A low energy fracture is defined as a fracture caused by falls on the same level as the person is located. Twenty consecutive patients were investigated yearly between 2002 and 2004, and 60 patients in 2005, totalling 120 patients. Criteria for inclusion were age >65 years, able to communicate, and with normal cognitive function, i.e. Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) >24 points Citation13. The MMSE is a validated questionnaire consisting of 10 items, used to evaluate cognitive function. Each item is given a score of 0–3 points, with a maximum total score of 30 points.

All patients were questioned about their weight and height. The nutritional status of the patients was evaluated by body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) and plasma albumin. Blood was sampled before the operation for analyses of haemoglobin, C-reactive protein (CRP), total calcium and calcium conjugated with albumin. During 2005, 15 patients underwent dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) to evaluate their osteoporotic state by BMD.

Data collection

One week post-operation, the patients were interviewed on the ward and asked about their average daily consumption of calcium-rich products and intake of calcium supplements before their hip fracture. In order to facilitate the interview with these elderly injured patients, we chose to assess dietary calcium intake using a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) modified from a questionnaire previously used by Michaelsson et al. Citation14. This questionnaire has open questions estimating daily consumption over the previous 6 months of dairy products including type and number of glasses of milk, yoghurt, numbers of cheese slices per day, and also supplementary calcium intake with calcium tablets with or without vitamin D. We used eight predefined frequency categories ranging from ‘never’ or ‘seldom’, to ‘many times per day’. One glass of milk and a dish of soured milk were calculated to contain 200 ml, thus with 232 mg calcium (116 mg/100 ml), and a slice of cheese was similarly calculated to contain 85 mg of calcium according to the Swedish Dairy Association Citation15.

Statistics

Mean values and standard deviations (±SD) were calculated for all variables. Student's t-test was used to compare means between men and women. Otherwise, non-parametric statistics were used as the number of observations was small and a non-normal distribution was probable. Spearman's rank correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the relationship between calcium intake and age, gender and nutritional indicators. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethics

All patients gave their informed consent before participation. The study was approved by the ethics committee of Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm (2002-06-12; 02-153).

Results

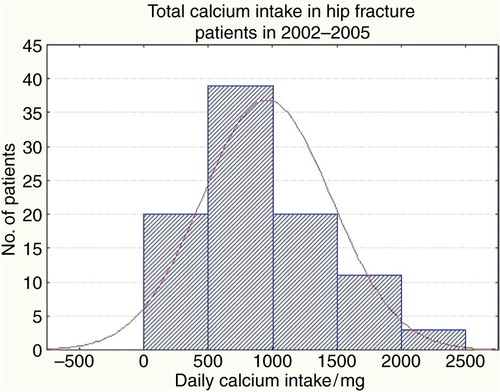

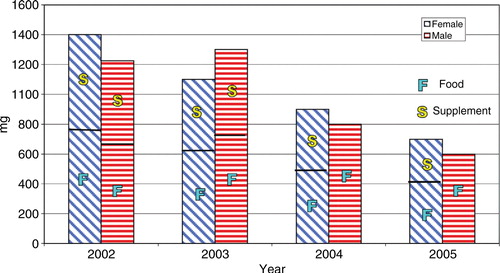

The study comprised 120 patients, 97 women and 23 men with a mean age of 78±9 years ( and ). The hip fractures were divided into two groups, with a cervical hip fracture in 62 patients (53%) and a trochanteric fracture in 58 patients (48%). and 2 show calcium intake during the whole observation period. The mean daily calcium intake was 685±306 mg from food and 283±372 mg from supplementation (mean±SD), respectively. Thus, the total calcium intake was 968±501 mg. Calcium intake through food was <800 mg/day in 74 patients (62%). A corresponding low intake from food and calcium supplementation combined was registered in 46 patients (38%) (). In total, 15 patients had a daily calcium intake <400 mg through food. Fifty-five patients (42%) had no calcium supplementation. The laboratory parameters are depicted in , and there were no correlations to calcium intake.

Table 1. Demographic, biochemical and calcium intake data in elderly patients with hip fractures through 2002–2005

Table 2. Mean values of study variables in 120 elderly patients with hip fractures

There was no significant difference in calcium intake between men and women in total or between the individual years ( and ). However, there was a trend towards lower intake during the last year of the study (), and there was a significantly decreased calcium intake from food and supplements in men during the last year. There was no correlation between calcium intake and age, gender, BMI, plasma calcium or albumin, and there was no significant difference in calcium intake between patients with a cervical hip fracture or a trochanteric fracture.

Figure 2. Mean calcium intake by food and supplementation in men and women with hip fractures from 2002 to 2005.

According to the DEXA examination of 15 patients, 12 patients had osteoporosis, i.e. a T-score below −2.5. Two patients had osteopenia (T score between –1 and –2.5) and one patient had a normal T-score. There was no correlation between calcium intake and BMD.

Discussion

In this study on calcium intake in 120 elderly patients with hip fracture during the years 2002–2005, we found a mean total daily calcium intake of 970 mg of which daily dietary calcium through milk, yoghurt and cheese was 686 mg (71%), and the mean daily calcium supplementation was 284 mg (29%). More than half of the patients had no supplementation. Nearly 40% of the patients had a calcium intake below the recommended 800 mg/day. Over the 4 years, there was a tendency to a gradually decreased calcium intake through food in 27% of patients and through supplements in 63% of patients. There was no gender difference in calcium intake.

In the treatment of established osteoporosis, the main role of calcium supplementation is as a general adjuvant therapeutic measure Citation16Citation17. However, several studies have shown that calcium supplementation rendering a total calcium intake of 1,200 mg/day may slow the rate of bone loss Citation18. Among healthcare workers, it has been difficult to reach a consensus on what should be considered as the physiological requirement of daily calcium intake. The reality is that currently we have no reliable method on which to determine the requirement of calcium Citation10. However, the NNR 2004 has recommended a daily calcium intake of 800 mg Citation10. Due to the high consumption of calcium rich foodstuffs, such as milk and milk products, the mean daily calcium intake in the Nordic countries is higher than the recommendation for almost all age-groups, i.e. 900–1,200 mg/day for women and 900–1,400 mg/day for men (NNR) Citation10. In contrast, much of the world's population has a calcium intake <500 mg/day Citation10, e.g. the intake in Japan is 400–500 mg/day due to a diet of mainly soybean, small fish with bone and vegetables Citation19. The calcium intake is even lower in other Asian countries and in Africa. Paradoxically, the highest incidence of osteoporotic fractures is found in developed countries with the highest calcium intake, arguing in favour of a more complex correlation to fractures than calcium intake alone.

According to the findings of our study, the mean calcium intake of patients with a hip fracture was sufficient, whereas more than one-third of the patients had a suboptimal intake. Since 1980, several studies have asserted that calcium intake via food and supplement was the best way to prevent and treat osteoporosis and hip fracture. However, the results are conflicting Citation14Citation16Citation20Citation21. For example, calcium supplementation alone has been reported to have a small positive effect on bone density Citation22. On the other hand, calcium supplementation was recently shown unlikely to be able to substantially reduce the fracture risk Citation23Citation24. There are Dutch results suggesting an increased risk of osteoporotic fractures in old age with a high life time calcium intake Citation2.

Surprisingly, in our study there was a trend toward a decreased calcium intake during the years 2002–2005. We do not have specific explanations for this finding, but one possible explanation could be the coincidental mass-medial warnings occurring at this time concerning milk consumption and its relation to atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Moreover, there were discussions of studies on osteoporotic hip fractures in postmenopausal women reporting that neither milk nor a high calcium diet appeared to reduce the risk of fracture Citation2Citation24. In countries such as the US, Italy, and Sweden, it has been suggested that there is almost no correlation between calcium intake and osteoporotic hip fracture Citation14Citation20Citation25. In the previously mentioned Dutch study, it was suggested that calcium might inhibit osteoblast activity in bone tissue Citation2.

A drawback of this study was that the levels of 25-OH-vitamin D were not measured, which is important in calcium absorption. However, the effectiveness of vitamin D alone in fracture prevention is unclear Citation26. One study reports no association with fracture risk Citation14, while others show a sustained effect on fewer hip fractures in institutionalised, frail, older people in combination with calcium supplements Citation27. Another study shows a reduced risk of hip fractures and other non-vertebral fractures among elderly women with such a combination therapy Citation28, as well as a study on elderly community dwelling residents Citation29. Furthermore, we did not have a matched control group to compare calcium intake. However, we were interested in the hip fracture patients’ calcium intake and the relation to RDI. A French study on institutionalized geriatric patients showed a mean calcium intake of 670±258 mg/day Citation30. The use of a FFQ as the only measure of calcium intake is a weakness of the study. This technique was validated by Michaelsson et al. Citation14

Conclusion

This study of patients with hip fracture showed that the mean calcium intake was well above the daily recommended intake regardless of gender, despite the general dominant incidence of osteoporotic hip fracture in women. However, more than one-third of the patients had an intake below the recommended level. There was no significant correlation between dietary calcium intake and age, gender or nutritional status. Further studies are suggested in order to seek mechanistic explanations for the paradox that subjects with sufficient or even high calcium intake still have a high incidence of hip fractures.

Conflict of interst and funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry to conduct this study.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the staff of the gero-orthopaedic ward for performing the investigation and Åsa Norling for performing the dietary recalls and collection of laboratory samples. In addition, we would like to thank Sten Dalbom for support in the performance of the statistical analysis, and all the co-workers at the chemical laboratories and dual energy X-ray absorptiometry at the osteoporosis unit at Karolinska University Hospital, Huddinge, Sweden.

References

- Grey A. Emerging pharmacologic therapies for osteoporosis. 2007; 12: 493-508

- Klompmaker TR. Lifetime high calcium intake increases osteoporositic fracture risk in old age. 2005; 65: 552-8

- Kanis JA. Diagnosis of osteoporosis and assessment of fracture risk. 2002; 359: 1929-36

- Keen R. Osteoporosis: strategies for prevention and management. 2007; 21: 109-22

- Nievis JW. Osteoporosis: the role of micronutrients. 2005; 81: 1232S-9S

- Sugimoto T. Calcium intake and bone mass. 2001; 11: 193-7

- Gennari C. Calcium and vitamin D nutrition and bone disease of the elderly. 2001; 4: 547-59

- Yukawa H, Suzuki T. Dietary calcium and women's health. 2001; 11: 157-62

- Lau EM, Suriwongpaisal P, Lee JK, Das De S, Festin MR, Saw SMet al.Risk factors for hip fracture in Asian men and women: the Asian osteoporosis study. 2001; 16: 572-80

- Nordic Nutrition Recommendations. 2004: integrating nutrition and physical activity. Nordiska ministerrådet, (Nordic Council of Ministers), 4th edition, Copenhagen, 2004.

- Dvorak MM, Riccardi D. Ca2+ as an extra cellular signal in bone. 2004; 35: 249-55

- Shoback D. Update in osteoporosis and metabolic bone disorders. 2007; 92: 747-53

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PH. Mini Mental Test/MMT. 1975; 12: 189-98

- Michaelsson K, Melhus H, Bellocco R, Wolk A. Dietary calcium and vitamin D intake in relation to osteoporotic fracture risk. 2003; 32: 694-703

- Arnemo M. Livsmedelstabal 2002, Statens Livsmedelsverle (A table of foods: energy and nutrition material. Swedish Dairy Association). Uppsala, 2001.

- Kaufman JM. Role of calcium and vitamin D in the prevention and the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: overview. 1995; 14 Suppl 3: 9-13

- Terrio K, Auld GW. Osteoporosis knowledge, calcium intake, and weight-bearing physical activity in three age groups of women. 2002; 27: 307-20

- Tang BM, Eslick GD, Nowson C, Smith C, Bensoussan A. Use of calcium in combination with vitamin D supplementation to prevent fractures and bone loss in people aged 50 years and older: a meta-analysis. 2007; 370: 657-66

- Zhang Y, Ojima T, Murata C. Calcium intake pattern among Japanese women across five stages of health behavior change. 2007; 17: 45-53

- Tavani A, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Calcium, dairy products, and the risk of hip fracture in women in Italy. 1995; 6: 554-7

- McLeod KM, McCann SE, Horvath PJ, Wactawski-Wende J. Predictors of change in calcium intake in postmenopausal women after osteoporosis screening. 2007; 137: 1968-73

- Shea B, Wells G, Cranney A, Zytanule N, Robinson V, Griffith Let al.Calcium supplementation on bone loss in postmenopausal women. 2007; 18: CD004526.

- Winzenberg T, Shaw K, Fryer J, Jones G. Effect of calcium supplementation on bone density in healthy children meta-analysis of randomised controlled trails. 2006; 333: 7572-754

- Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, DeLaet C, Johnell O, Eisman JAet al.A meta-analysis of milk intake and fracture risk: low utility for case finding. 2005; 16: 799-804

- Feskanich D, Willett WC, Colditz GA. Calcium, vitamin D, milk consumption, and hip fractures: a prospective study among postmenopausal women. 2003; 77: 504-11

- Avenell A, Gillespie WJ, Gillespie LD, O'Connell DL. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures associated with involutional and post-menopausal osteoporosis. 2005; 3: CD000227.

- Chapuy MC, Pamphile R, Paris E, Kempf C, Schlichting M, Arnaud Set al.Combined calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation in elderly women: confirmation of reversal of secondary hyperparathyroidism and hip fracture risk: the Decalyos II study. 2002; 13: 257-64

- Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, Brun J, Crouzet B, Arnaud Set al.Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in the elderly women. 1992; 327: 1637-42

- Larsen ER, Mosekilde L, Foldspang A. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation prevents osteoporotic fractures in elderly community residents: a pragmatic population-based 3-year intervention study. 2004; 19: 370-8

- Deplas A, Debiais F, Alcalay M, Bontoux D, Thomas P. Bone density, parathyroid hormone, calcium and vitamin D, nutritional status of institutionalized elderly subjects. 2004; 8: 400-4