Abstract

Objective

This paper reviews the evidence related to the association of dietary pattern with coronary heart disease (CHD), strokes, and the associated risk factors among adults in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

Methods

A systematic review of published articles between January 1990 and March 2015 was conducted using Pro-Quest Public Health, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar. The term ‘dietary pattern’ refers to data derived from dietary pattern analyses and individual food component analyses.

Results

The search identified 15 studies. The available data in the MENA region showed that Western dietary pattern has been predominant among adults with fewer adherences to the traditional diet, such as the Mediterranean diet. The Western dietary pattern was found to be associated with an increased risk of dyslipidaemia, diabetes, metabolic syndrome (MetS), body mass index (BMI), and hypertension. The Mediterranean diet, labelled in two studies as ‘the traditional Lebanese diet’, was negatively associated with BMI, waist circumference (WC), and the risk of diabetes, while one study found no association between the Mediterranean diet and MetS. Two randomised controlled trials conducted in Iran demonstrated the effect of the dietary approach to stop hypertension (DASH) in reducing metabolic risk among patients with diabetes and MetS. Likewise, the consumption of dairy products was associated with decreased blood pressure and WC, while the intake of whole grains was associated with reduced WC. In addition, the high consumption of black tea was found to be associated with decreased serum lipids. The intake of fish, vegetable oils, and tea had a protective effect on CHD, whereas the intake of full-fat yoghurt and hydrogenated fats was associated with an increased risk of CHD.

Conclusion

There appears to be a significant association of Western dietary pattern with the increased risk of CHD, strokes, and associated risk factors among adults in the MENA region. Conversely, increased adherence to Mediterranean and/or DASH dietary patterns or their individual food components is associated with a decreased risk of CHD and the associated risk factors. Therefore, increasing awareness of the high burden of CHD and the associated risk factors is crucial, as well as the need for nutrition education programs to improve the knowledge among the MENA population regarding healthy diets and diet-related diseases.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a principal cause of death and disability worldwide; with the number of CVD mortalities increasing globally from 14.4 million in 1990 to 17.5 million in 2005, in particular from coronary heart disease (CHD) and strokes (Citation1). The shift in dietary patterns and the development of nutrition transitions characterised by changes in food supply and intake has been one of the major factors in the high prevalence of CHD and strokes around the world. Numerous factors have contributed to the nutrition transition phenomenon all over the world. Globalisation, a key factor, has had a major effect on changes in lifestyle, food production, modern food processing, and marketing. Furthermore, other factors such as urbanisation, cultural changes, economic development, social improvement, global mass media, and industrialisation have led to predictable shifts in diet and lifestyle (Citation2).

The Middle East and North Africa region (MENA) includes 19 countries. The five countries included from North Africa are Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Libya, and Tunisia, and the 14 countries included from the Middle East are Bahrain, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. The MENA region has almost 355 million people; however, only 8% live in high-income countries (the six Arabic Gulf countries) where the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita is more than US$12,976, while 7% live in low-income countries, such as Yemen, where the GDP per capita is less than US$1,005. The rest of the MENA population (85%) lives in middle-income countries where the GDP per capita is between US$1,006 and US$12,795, such as Iran, Lebanon, Algeria, and Egypt (Citation2, Citation3).

The MENA region is facing high development and urbanisation, which has resulted in an explosion in the prevalence of CHD and strokes, the key forms of CVD, and the associated risk factors. The mortality rates of ischemic heart disease and cerebrovascular disease (stroke) are estimated to triple between 1990 and 2020 in the majority of MENA countries (Citation4). Several countries in the region have also reported high proportions of CVD mortality. For example, studies from Lebanon and Syria have reported that CVD contributes to 60% and 45% of the total mortality, respectively (Citation5, Citation6). Furthermore, a high prevalence of CHD has been reported in several countries in the MENA region. For instance, one study from Iran reported 12.7% prevalence of CHD in its study population (Citation7). Similar findings have been reported in studies from Jordan (5.9%), Tunisia (men, 12.5%; women, 20.6%), and Saudi Arabia (5.5%) (Citation8–Citation10).

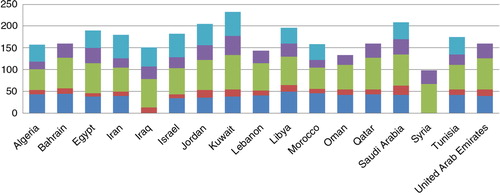

The MENA region is also witnessing alarming rates of CVD risk factors exceeding those in developed countries. The International Diabetes Foundation (IDF) showed that in 2011 the MENA region had the highest prevalence of diabetes (12.5%) compared to other regions worldwide such as Europe (6%) and Southeast Asia (8.6%) (Citation11). Likewise, the World Health Organization (WHO) data has revealed a significant increase in the prevalence of CVD risk factors within MENA countries, especially obesity which is responsible for almost 30–40% of CVDs () (Citation12).

Fig. 1 The burden of CHD risk factors (%) in the Middle East and North Africa countries in 2010. Data adopted from World Health Organization (Citation12).

A number of studies have also been published related to the association between diet and chronic diseases in the MENA region. Nevertheless, only one systematic review focusing on nutrition transition and the burden of CVD risk factors in the MENA region has been published (Citation13); however, the association between diet and the presence of CHD and strokes in the region was not examined. Therefore, this paper attempts to fill this gap and review the available literature related to the association of dietary patterns with CHD, strokes, and associated risk factors among adults in MENA countries.

Methods

Data sources

Literature searches were conducted using Pro-Quest Public Health, MEDLINE, and Google Scholar to identify both observational studies and randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that were published in English between January 1990 and March 2015. The reference lists of the original articles were also manually searched to identify any further relevant studies. The review articles were also checked. The search terms are shown in Box 1.

Box 1. Selected search terms

Dietary patterns

1. ‘food consumption patterns’ OR ‘dietary patterns’ OR ‘food habits’ OR ‘eating patterns’ OR ‘food items’ OR ‘diet’

The MENA region

2. ‘The MENA region’ OR ‘the Middle East’ OR ‘North Africa’ OR each country individually

Cardiovascular disease

3. ‘cardiovascular disease’ OR ‘coronary heart disease’ OR ‘cardiovascular patients’ OR ‘myocardial infarction’ OR ‘coronary artery disease’ OR ‘stroke’ OR ‘cerebrovascular disease’

Associated risk factors

4. ‘diabetes mellitus’ OR ‘NIDDM’ OR ‘hypertension’ OR ‘high blood pressure’ OR ‘metabolic syndrome’ OR ‘dyslipidaemia’ OR ‘hypercholesterolemia’ OR ‘high cholesterol’ OR ‘overweight’ OR ‘obesity’ OR ‘BMI’

5. #1 AND #2 AND #3

6. #1 AND #2 AND #4

Selection of studies

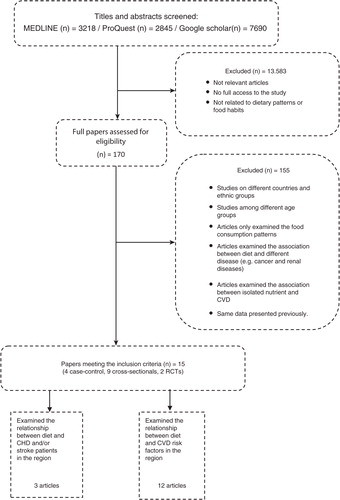

The search strategy used certain inclusion criteria that included studies that examined the association of dietary pattern with CHD and/or stroke and/or at least one of the related risk factors: hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, metabolic syndrome (MetS), overweight, and obesity in the MENA countries. The term ‘dietary pattern’ refers to data derived from either dietary pattern or individual food component analyses. All the included studies were required to only include individuals aged 18 above. All types of populations and socio-demographic backgrounds were included. Furthermore, the review was limited to studies published in English. If the study was carried out among both adults and adolescents or children, only the data on the adult participants were presented. Studies that only reported the prevalence of CHD, strokes, or related risk factors without reporting their association with diet were also excluded. Similarly, this review also excluded studies that only examined the food consumption patterns or food habits without reporting their association with the risk of CHD or strokes or associated risk factors. Studies that only linked isolated nutrients with CHD or strokes or associated risk factors were also excluded. The method to assess which studies were appropriate was based on a hierarchical approach: searching titles, abstracts, and then the full-text papers. shows the selection process.

Data abstraction and the quality assessment

Data extracted from each study included the following: the country of study, publication year or survey year, study design, the age and gender of the study participants, sample size, a dietary assessment tool, the definition of dietary patterns, diagnosis criteria of CHD, stroke, and related risk factors, the main outcomes and the strengths and limitations of the study. The quality of the included studies was assessed according to the Research Triangle Institute-University of North Carolina, Evidence-based Practice Centre (RTI-UNC EPC) for RCTs, and according to hierarchies of evidence and critical appraisal check list for observational studies (Citation14, Citation15). The quality assessment of included studies in the systematic review is shown in Table , 2 , and 3 .

Table 1 Quality criteria summary for RCTs studies on the association of dietary patterns with CHD, strokes, and associated risk factors

Table 2 Domains and elements for RCTs studies

Table 3 Quality criteria summary for the observational studies on the association of dietary patterns with CHD, strokes, and associated risk factors in the MENA region

Data synthesis

The analysis of included studies involved a narrative synthesis to examine the objective of this review due to the non-homogenous nature of included studies. The synthesis started with an initial summary of the main characteristics and outcomes of included studies through organised tables and assessed the strength and limitations of studies. It also included a clear description of the papers in the review and a summary of the main results, and considered the association between individual studies and between the findings of diverse studies.

Results

The literature search identified 15 studies that met the inclusion criteria and were all from the Middle East: six papers were published in the 2000s and nine papers in the last 4 years. Of the included studies, three studies evaluated the dietary patterns and/or specific food items among CHD and stroke patients, and 12 studies examined the association of dietary patterns and/or specific food items with CVD risk factors in the MENA region. Of the studies that reported the association between CVD risk factors and dietary patterns, three investigated diabetes, five focused on MetS, one examined overweight and obesity, one addressed blood lipids and three investigated multiple risk factors.

Out of the 15 included articles, 10 were located in Iran, 3 in Lebanon, and 2 in Saudi Arabia. There was a lack of data from the majority of the MENA. Regarding the study designs, four were case–control, nine were cross-sectional, and two were RCTs. Furthermore, the main populations included in this review were university students (one study), patients (six studies), and the general population (eight studies). The sample sizes in the included studies ranged from 31 to 1,764 subjects and the response rates ranged from 24.3% (Citation16) to 95.9% (Citation17). Details of the research methods and key findings of the included articles are summarised in Table and 5 .

Table 4 Summary of characteristics and main findings from the included studies examined the dietary patterns among CHD and stroke patients in the MENA countries

Table 5 Summary of characteristics and main findings from the included studies examined the association between diet and CVD risk factors in the MENA countries

Association of dietary patterns with CHD and strokes in the MENA region

There were only three case–control studies that have examined the dietary intake among CHD (Citation18) and stroke patients in the MENA region (Citation19, Citation20), all of which were carried out in Iran. A summary of these studies is shown in . The studies examined the food consumption patterns among CHD and stroke patients and compared them with matched controls to determine whether the intake of various food items was associated with the risk of CHD and strokes. In CHD patients, the daily intake of fish, vegetable oils, and tea had a protective effect on CHD, whereas the daily intake of full-fat yoghurt and hydrogenated fats was positively associated with an increased risk of CHD (Citation18). In stroke patients, the consumption of potatoes was associated with an increased risk of stroke (Citation19), while no association was found between the intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and the risk of stroke (Citation20). In addition, when compared to the control group, stroke patients had a higher consumption of high-fat dairy, pulses, and fruits and a lower consumption of low-fat dairy and non-hydrogenated vegetable oils (Citation19).

Association between dietary patterns and CVD risk factors in the MENA region

In order to clarify the association between diverse dietary patterns and the risk of CHD and strokes, it is crucial to examine the effect of the dietary intake on various risk factors such as blood glucose levels, blood lipids level, blood pressure, and body weight (Citation21). Twelve studies have examined the relationship of dietary patterns and/or individual food items with CVD risk factors among adults in the MENA countries. The details of the methodologies and key findings of the included studies are summarised in .

Type 2 diabetes

A cross-sectional survey among Iranian adults with Impaired Glucose Tolerance (IGT) found that a Western dietary pattern (rich in sugar, butter, soda, sweets, eggs, hydrogenated fat, and mayonnaise) was significantly associated with increased levels of triacylglycerol (OR=1.76, 95% CI: 1.01–3.07) and blood pressure (OR=2.62, 95% CI: 1.32–5.23), while a vegetarian dietary pattern (rich in green leafy vegetables, fruits, potatoes, and legumes) was associated with increased plasma glucose levels (OR=2.26, 95% CI: 1.25–4.06) after adjustment for the confounding variables (Citation22).

Another case–control study conducted among type 2 diabetes patients in Lebanon using factor analysis identified four main dietary patterns: refined grains and desserts (rich in pastas, pizza, white bread, and desserts), a traditional Lebanese diet (rich in olives oil, fruits and vegetables, whole wheat bread, and traditional dishes), fast food (rich in French fries, fast-food sandwiches, mixed nuts, and whole fat diary), and meat and alcohol pattern (rich in eggs, alcohol, read meats, and sweetened beverages) (Citation23). This study showed, after adjustment for confounding factors, that the refined grains and dessert dietary pattern (OR=3.85, 95% CI: 1.13–11.23) and fast-food dietary pattern were associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes (OR=2.80, 95% CI: 1.41–5.59), whereas, the traditional Lebanese dietary pattern was associated with a decreased risk of type 2 diabetes (OR=0.46, 95% CI: 0.22–0.97) (Citation23). Similarly, a randomised crossover clinical trial conducted among patients with type 2 diabetes in Iran also reported the beneficial effects of the DASH diet on several cardio metabolic risks (Citation24). The study demonstrated that when compared to the control group, there were significant reductions in fasting blood glucose (FBG), low-density lipoproteins (LDL) cholesterol, total cholesterol (TC), and blood pressure levels among the participants who followed the DASH diet for 8 weeks, while there was a significant increase in high-density lipoproteins (HDL) cholesterol level (Citation24).

Obesity

A number of studies have supported the fact that the traditional Mediterranean diet is associated with a reduction in overweight and obesity. For example, a cross-sectional survey in Lebanon showed that the Mediterranean diet (whole cereals, legumes, olive oil, fruit, fish, and vegetables) was negatively associated with a high waist circumference (WC) and body mass index (BMI) in both genders (Citation25). Likewise, according to a study conducted by Naja et al. (Citation23), the traditional Lebanese dietary pattern (rich in olives oil, fruits and vegetables, whole wheat bread) was also negatively associated with elevated BMI and WC among type 2 diabetes patients. The same study also reported that the refined grains and desserts dietary pattern, the fast-food dietary pattern, and the meat and alcohol dietary pattern were positively associated with high BMI and WC among type 2 diabetes patients (Citation23).

Metabolic syndrome

A study analysing data from a nation-wide survey in Lebanon showed that the fast food and desserts dietary pattern (rich in fast-food sandwiches, pizzas, desserts, soft drinks) was associated with an increased risk of MetS (OR=3.13, 95% CI: 1.36–7.22) and hyperglycaemia (OR=3.81, 95% CI: 1.59–9.14), and the high-protein dietary pattern (rich in chicken, fish, low-fat dairy products, meats) was associated with an increased risk of high blood pressure (OR=2.98, 95% CI: 1.26–7.02) (Citation16). There was no association between the traditional Lebanese dietary pattern (rich in olives, fruits, legumes, vegetable oil, grains), which is similar to traditional local Mediterranean food, and the risk of MetS (Citation16). Another study from Iran reported that a dietary pattern rich in cereals, fruits and vegetables, legumes, fish, eggs, and dairy products was associated with a reduced risk of MetS, while a dietary pattern rich in pasta was positively associated with increased blood lipids (Citation17).

A study conducted among Iranian adults showed that the intake of whole grains was associated with reduced hypertriglyceridemia waist (HW) (serum triacylglycerol concentration and WC) and WC (Citation26). Moreover, another survey in Iran, which examined the relationship between MetS and the intake of dairy products, indicated that the consumption of dairy products was associated with decreased blood pressure and WC (Citation27). Similarly, an RCT conducted in Iran demonstrated a beneficial effect of the DASH diet in reducing the metabolic risk among patients with MetS (Citation28). For example, when compared with the control group, significant reductions in body weight, triglycerides, blood pressure, and FBG levels were observed in both males and females in the DASH diet group (Citation28).

Abnormal blood lipids

One study in Saudi Arabia showed that subjects who consumed more than six cups of black tea per day (>480 ml) were significantly less likely to have dyslipidaemia including, high TC (OR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.41–0.97), high triglycerides (OR=0.56, 95% CI: 0.35–0.86), and high very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) (OR=0.61, 95% CI: 0.39–0.93) (Citation29). However, this study did not find any association between black tea consumption and high LDL and, HDL (Citation29).

Multiple CVD risk factors

In Iran, a study found that a healthy dietary pattern (rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes, fruit juices, poultry, whole grains) was significantly associated with a reduced risk of dyslipidaemia (OR=0.36, 95% CI: 0.19–0.53), hypertension (OR=0.33, 95% CI: 0.17–0.60) (Citation30). Conversely, the Western dietary pattern (rich in red meat, high-fat dairy products, refined grains, hydrogenated fats, sweets, soft drinks, eggs, pizza) was significantly associated with an increased risk of dyslipidaemia (OR=2.59, 95% CI: 1.41–4.76), hypertension (OR=2.61, 95% CI: 1.27–5.19) (Citation30). The Iranian dietary pattern (rich in potato, tea, refined grains, whole grains, legumes, hydrogenated fats) was only significantly associated with an increased risk of dyslipidaemia (OR=1.73, 95% CI: 1.02–2.99) (Citation30). In Saudi Arabia, a food consumption survey showed a significant association between the high intake of energy derived from fatty foods and high BMI and hypertension levels in both genders (Citation31). Similarly, a significant association was found between the high consumption of salty foods and hypertension, while a negative association was found between the consumption of vegetables, grains and beans and BMI and hypertension in both genders (Citation31).

Discussion

This review has revealed that specific dietary patterns and/or the individual food components of a diet are associated with CHD, strokes, and associated risk factors among adults in MENA countries. When looking at the individual food components of a diet, studies have shown that the intake of fish, vegetable oils and black tea had a protective effect on CHD, while the intake of full-fat yoghurt and hydrogenated fats were positively associated with the risk of CHD (Citation18–Citation20). These findings were similar to those reported among the US population (Citation32, Citation33), except for the effect of black tea on CHD (Citation34). In addition, this review found a significant positive association between potato consumption and the risk of strokes (Citation19), and this has been explained by the high glycaemic index and the high amount of carbohydrates which make potato a type of food that increases the risk of strokes. Similar results have been reported in Australia leading to conclusions that foods with the high amount of glycaemic index, such as potatoes, may increase the risk of stroke death (Citation35).

The MENA region has witnessed vast changes in dietary patterns resulting from the marked shifts in socio-economic status and demographics, as well as rapid urbanisation and modernisation during the last few decades. This review also identified that the Western dietary pattern rich in sweets, fatty foods, meat, whole dairy products, fast food, salty nuts, and canned foods has become predominant among the majority of the MENA population (Citation16, Citation22) (Citation23, Citation30). These results are consistent with available food consumption surveys among adults in the MENA region, such as in Lebanon, Egypt and Iran, which have indicated that eating patterns are mainly characterised by a high intake of sugar, meat, soft drinks and refined grain, as well as low consumption of fish, fruits, vegetables, legumes and whole grains (Citation36–Citation38). Further, using a factor analysis of dietary intake data from a national survey in Iran, it has also been reported that the majority of the study subjects were consuming the Western dietary pattern (high in sweets, fast foods, salty nuts, canned foods) (Citation39). These findings were also consistent with the FAO food balance sheets data, which indicated that the availability of sugar and sweeteners (kg/person/year) has gradually increased gradually in the MENA region during the last four decades especially in oil-rich countries such as Saudi Arabia and Algeria (Citation40).

The findings of this review also indicate that adopting the Western dietary pattern is significantly associated with almost all CVD risk factors, including an increased risk of obesity, blood lipids, hypertension, diabetes and MetS in MENA populations (Citation16, Citation22) (Citation23, Citation30). Similar results have been reported among US and Mexican populations (Citation41, Citation42). On the other hand, the Mediterranean diet, also known as the healthy diet, is the traditional diet in North African countries and three Middle Eastern countries, Syria, Israel and Lebanon, and it has been inversely associated with obesity, diabetes, and MetS among the same populations (Citation16, Citation23) (Citation25). Therefore, there is increasing evidence illustrating the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet in the reduction of morbidity and mortality from CVD (Citation43, Citation44). The Mediterranean dietary pattern mainly consists of a high consumption of fruits, vegetables, wholegrain cereals, legumes, nuts, olive oil, fish and seafood. It is also characterised by a moderate consumption of dairy products, eggs, poultry and wine (Citation45). These individual food elements offer many benefits for cardiovascular health and prevention of CVD, as they are good sources of monounsaturated fatty acids, antioxidants, magnesium, fibre, and polyphenols (Citation45).

Limitation of the review

The major limitation in this review was the lack of studies from several countries in the MENA region that have examined eating patterns among CHD and stroke patients; only three case–control studies were identified and all of them were from Iran. In addition, the majority of the included studies in the review utilised cross-sectional design, and thus failed to assess causal relationships. Further, most of the studies reported dietary patterns using food frequency questionnaires which might have increased the risk of recall bias and overestimated the consumption of healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables. Also, some of the studies that reported (Citation16, Citation23) significant associations between diet and CVD had a very wide confidence intervene for odd ratios (ORs) which may indicate that the results of these studies are not reliable either due to small sample sizes or the sampling procedures are not representative.

Conclusion

This review demonstrates that Western dietary patterns, which are mainly characterised by high consumption of sugar, fatty foods, meat, and refined grains, and low consumption of fruits, vegetables, fibre, and whole grains, are very common in the MENA region and adherence to this Western diet is linked with an increased risk of CHD, strokes, and associated risk factors among adult populations of the MENA countries. On the contrary, adherence to the Mediterranean diet or DASH diet and/or individual food components of these diets appears to be associated with a decreased risk of CHD and associated factors. Therefore, increasing awareness of the high prevalence of CVD and associated risk factors among the public is crucial. In addition, there is an urgent need for nutrition education programs among all segments of the MENA population to increase awareness regarding healthy diets and diet-related chronic diseases. This should be combined with encouragement of healthy lifestyle patterns, including increasing physical activity and a reduction in smoking, to enhance the prevention of heart disease and associated risk factors. Furthermore, there is a crucial need for further intervention studies focusing on a range of diverse cohorts in relation to CHD and strokes, in order to help in providing nutritional recommendations to control CVD among the population of the MENA region.

Authors' contributions

NA designed the concept of study and prepared the manuscript draft. FA has provided guidance on the study design and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest and funding.

Acknowledgements

Mrs. Najlaa Aljefree was supported by a scholarship from King Abdul Aziz University for Nutrition and Dietetics. The King Abdul Aziz University had no role in the design, analysis, or writing of this paper.

References

- Fuster V, Kelly BB. Promoting cardiovascular health in the developing world: a critical challenge to achieve global health. 2010; Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Golzarand M, Mirmiran P, Jessri M, Toolabi K, Mojarrad M, Azizi F. Dietary trends in the Middle East and North Africa: an ecological study (1961 to 2007). Public Health Nutr. 2012; 15: 1835–44. [PubMed Abstract].

- World Bank Group. Middle East & North Africa. Available from: http://www.worldbank.org/en/region/mena [cited 9 October 2013]..

- Yusuf S, Reddy S, Ôunpuu S, Anand S. Global burden of cardiovascular diseases part I: general considerations, the epidemiologic transition, risk factors, and impact of urbanization. Circulation. 2001; 104: 2746–53. [PubMed Abstract].

- Maziak W, Rastam S, Mzayek F, Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Keil U. Cardiovascular health among adults in Syria: a model from developing countries. Ann Epidemiol. 2007; 17: 713–20. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Sibai AM, Fletcher A, Hills M, Campbell O. Non-communicable disease mortality rates using the verbal autopsy in a cohort of middle aged and older populations in Beirut during wartime, 1983–93. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001; 55: 271–6. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Nabipour I, Amiri M, Imami SR, Jahfari SM, Shafeiae E, Nosrati A, etal. The metabolic syndrome and nonfatal ischemic heart disease; a population-based study. Int J Cardiol. 2007; 118: 48–53. [PubMed Abstract].

- Al-Nozha MM, Arafah MR, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Maatouq MA, Khan NB, Khalil MZ, etal. Coronary artery disease in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2004; 25: 1165–71. [PubMed Abstract].

- Ben Romdhanee H, Skhirii H, Khaldi R, Oueslati A. Transition épidémiologique et transition alimentaire et nutritionnelle en Tunisie [Epidemiological Transition and food and nutrition transition in Tunisia]. L'approche causale appliquée à la surveillance alimentaire et nutritionnelle en Tunisie [The causal approach applied to food, and nutrition surveillance in Tunisia]. 2002; 41: 7–27. Montpellier: CIHEAM; 2002, pp. 7–27. (Options Méditerranéennes: Série B. Etudes et Recherches; n. 41)..

- Mohannad N, Mahfoud Z, Kanaan M, Balbeissi A. Prevalence and predictors of non-fatal myocardial infarction in Jordan. East Mediterr Health J. 2008; 14: 819.

- Whiting DR, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011; 94: 311–21. [PubMed Abstract].

- WHO. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. 2011; Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Nasreddine L, Mokdad A, Adra N, Tabet M, Hwalla N. Nutrition transition and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Middle East and North Africa countries: reviewing the evidence. Ann Nutr Metab. 2010; 57: 193–203. [PubMed Abstract].

- Greenhalgh T. How to read a paper: the basics of evidence-based medicine. 2001; London: BMJ Books.

- West SL, King V, Carey TS, Lohr KN, McKoy N, Sutton SF. Systems to rate the strength of scientific evidence: agency for healthcare research and quality. 2002; North Carolina: US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Naja F, Nasreddine L, Itani L, Adra N, Sibai A, Hwalla N. Association between dietary patterns and the risk of metabolic syndrome among Lebanese adults. Eur J Nutr. 2013; 52: 97–105. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Hassan S, Hanachi P. Dietary patterns and the metabolic syndrome in middle aged women Babol, Iran. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2009; 18: 285–92. [PubMed Abstract].

- Amani R, Noorizadeh M, Rahmanian S, Afzali N, Haghighizadeh MH. Nutritional related cardiovascular risk factors in patients with coronary artery disease in IRAN: a case-control study. Nutr J. 2010; 9: 70. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Mohammad SM, Forough SM. A case-control study on potato consumption and risk of stroke in Central Iran. Arch Iran Med. 2013; 16: 172.

- Niknam M, Saadatnia M, Shakeri F, Keshteli AH, Esmaillzadeh A. Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages in relation to stroke: a case-control study. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2013; 64: 1–6. [PubMed Abstract].

- Schulze MB, Hoffmann K. Methodological approaches to study dietary patterns in relation to risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. Br J Nutr. 2006; 95: 860–9. [PubMed Abstract].

- Amini M, Esmaillzadeh A, Shafaeizadeh S, Behrooz J, Zare M. Relationship between major dietary patterns and metabolic syndrome among individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. Nutrition. 2010; 26: 986–92. [PubMed Abstract].

- Naja F, Hwalla N, Itani L, Salem M, Azar ST, Zeidan MN, etal. Dietary patterns and odds of Type 2 diabetes in Beirut, Lebanon: a case–control study. Nutr Metab. 2012; 9: 111.

- Azadbakht L, Fard NRP, Karimi M, Baghaei MH, Surkan PJ, Rahimi M, etal. Effects of the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) eating plan on cardiovascular risks among type 2 diabetic patients a randomized crossover clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2011; 34: 55–7. [PubMed Abstract] [PubMed CentralFull Text].

- Issa C, Darmon N, Salameh P, Maillot M, Batal M, Lairon D. A Mediterranean diet pattern with low consumption of liquid sweets and refined cereals is negatively associated with adiposity in adults from rural Lebanon. Int J Obes. 2010; 35: 251–8.

- Esmaillzadeh A, Mirmiran P, Azizi F. Whole-grain intake and the prevalence of hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype in Tehranian adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005; 81: 55–63. [PubMed Abstract].

- Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi F. Dairy consumption is inversely associated with the prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in Tehranian adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005; 82: 523–30. [PubMed Abstract].

- Azadbakht L, Mirmiran P, Esmaillzadeh A, Azizi T, Azizi F. Beneficial effects of a dietary approaches to stop hypertension eating plan on features of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2005; 28: 2823–31. [PubMed Abstract].

- Hakim IA, Alsaif MA, Aloud A, Alduwaihy M, Al-Rubeaan K, Rahman Al-Nuaim A, etal. Black tea consumption and serum lipid profiles in Saudi women: a cross-sectional study in Saudi Arabia. Nutr Res. 2003; 23: 1515–26.

- Esmaillzadeh A, Azadbakht L. Food intake patterns may explain the high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors among Iranian women. J Nutr. 2008; 138: 1469–75. [PubMed Abstract].

- Abdel-Megeid FY, Abdelkarem HM, El-Fetouh AM. Unhealthy nutritional habits in university students are a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases. Saudi Med J. 2011; 32: 621–7. [PubMed Abstract].

- König A, Bouzan C, Cohen JT, Connor WE, Kris-Etherton PM, Gray GM, etal. A quantitative analysis of fish consumption and coronary heart disease mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2005; 29: 335–46. [PubMed Abstract].

- Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS, Anand SS. A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009; 169: 659–69. [PubMed Abstract].

- Vita JA. Tea consumption and cardiovascular disease: effects on endothelial function. J Nutr. 2003; 133: 3293S–7S. [PubMed Abstract].

- Kaushik S, Wang JJ, Wong TY, Flood V, Barclay A, Brand-Miller J, etal. Glycemic index, retinal vascular caliber, and stroke mortality. Stroke. 2009; 40: 206–12. [PubMed Abstract].

- Nasreddine L, Hwalla N, Sibai A, Hamzé M, Parent-Massin D. Food consumption patterns in an adult urban population in Beirut, Lebanon. Public Health Nutr. 2006; 9: 194–203. [PubMed Abstract].

- Yahia N, Achkar A, Abdallah A, Rizk S. Eating habits and obesity among Lebanese university students. Nutr J. 2008; 7: 1–6.

- Khorshed A, Ibrahim N, Galal C, Harrison G, Galal M, Basyoni A, etal. Development of food consumption monitoring system in Egypt. Adv Agric Res Egypt. 1998; 1: 163–217.

- Mohammadifard N, Sarrafzadegan N, Nouri F, Sajjadi F, Alikhasi H, Maghroun M, etal. Using factor analysis to identify dietary patterns in Iranian adults: Isfahan healthy heart program. Int J Public Health. 2012; 57: 235–41. [PubMed Abstract].

- FAO. Food balance sheets FAOSTAT. 2014; Rome: FAO.

- Lutsey PL, Steffen LM, Stevens J. Dietary Intake and the development of the metabolic syndrome the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Circulation. 2008; 117: 754–61. [PubMed Abstract].

- Denova-Gutiérrez E, Castañón S, Talavera JO, Gallegos-Carrillo K, Flores M, Dosamantes-Carrasco D, etal. Dietary patterns are associated with metabolic syndrome in an urban Mexican population. J Nutr. 2010; 140: 1855–63.

- de Lorgeril M, Salen P, Martin JL, Monjaud I, Delaye J, Mamelle N. Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors, and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1999; 99: 779–85. [PubMed Abstract].

- Zarraga IG, Schwarz ER. Impact of dietary patterns and interventions on cardiovascular health. Circulation. 2006; 114: 961–73. [PubMed Abstract].

- Kastorini C-M, Panagiotakos DB. Dietary patterns and prevention of type 2 diabetes: from research to clinical practice; a systematic review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2009; 5: 221–7. [PubMed Abstract].