Abstract

Background: Traditional forms of masculinity strongly influence men's and women's wellbeing.

Objective: This study has two aims: (i) to explore notions of various forms of masculinities in young Nicaraguan men participating in programs addressing sexual health, reproductive health, and/or gender equality and (ii) to find out how these young men perceive their involvement in actions aimed at reducing violence against women (VAW).

Design: A qualitative grounded theory study. Data were collected through six focus groups and two in-depth interviews with altogether 62 young men.

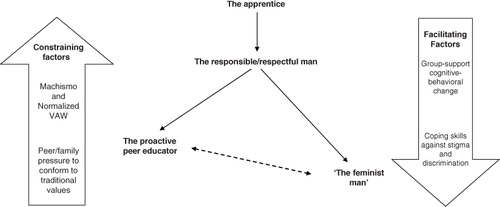

Results: Our analysis showed that the informants experienced a process of change, labeled ‘Expanding your mind’, in which we identified four interrelated subcategories: The apprentice, The responsible/respectful man, The proactive peer educator, and ‘The feminist man’. The process showed how an increased awareness of gender inequities facilitated the emergence of values (respect and responsibility) and behavior (thoughtful action) that contributed to increase the informant's critical thinking and agency at individual, social, and political levels. The process was influenced by individual and external factors.

Conclusions: Multiple progressive masculinities can emerge from programs challenging patriarchy in this Latin American setting. The masculinities identified in this study show a range of attitudes and behaviors; however, all lean toward more equitable gender relations. The results suggest that learning about sexual and reproductive health does not directly imply developing more gender-equitable attitudes and behaviors or a greater willingness to prevent VAW. It is paramount that interventions to challenge machismo in this setting continue and are expanded to reach more young men.

This article focuses on emerging forms of masculinities that will hopefully improve health for both men and women. Gender can be understood as a set of social relations that organize our social practice and interactions between men and women in a given culture (Citation1, Citation2). However, these interactions are often inequitable, defined by power imbalances between and within genders (Citation1). In many societies, these inequalities are representations of a patriarchal system of beliefs giving men authority over women (Citation3). Nevertheless, not all men have the same amount of power in a given society. Connell (Citation2) proposes that there are different types of masculinities, which are related to each other in diverse ways (relations of hegemony, subordination, complicity, and marginalization). Among these, hegemonic masculinity emerges as a key concept. It is defined as ‘the configuration of gender practice which embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of the legitimacy of patriarchy, which guarantees the dominant position of men and the subordination of women’ (Citation2). In other words, it represents the ideal of what it is to be a man in a given society. However, it is not a static entity: it changes over time and is continuously challenged by men and women who oppose it (Citation4).

Although the concept of hegemonic masculinity has been used extensively in many research fields, it has also been criticized. Demetriou (Citation5) and Hirose and Kei-ho Pih (Citation6) have pointed out that the construction of hegemonic masculinities can also be influenced by features of subordinated and marginalized masculinities reinforcing its domination. Howson has criticized Connell's theory for lacking an emphasis on how ambivalent and protest femininities influence gender politics (Citation7). In addition, even if it has been argued that Western constructions of masculinities have a strong influence on their local and regional counterparts in other parts of the world (Citation8), regional and local hegemonic forms of masculinity are also shaped by other factors, such as local traditions and migration (Citation4, Citation9–Citation11). One recent criticism of approaching masculinity as a plural entity is that such an approach focuses too much attention on the differing rather than the common practices that men share (Citation12). Other authors have questioned the clarity of Connell's theory, pointing to its ambiguous and sometimes blurred definition (Citation13–Citation15). Nevertheless, we agree with Connell in her acknowledgement of these criticisms and reformulation of the hegemonic masculinity concept, stressing the relevance of change, power relations, and multiplicity in the study of masculinities (Citation4).

Masculinities in Latin America

In Latin America, machismo has historically been viewed as a set of hegemonic masculinities that legitimizes patriarchy in this setting (Citation16 Citation17). Rather than a single set of defined behaviors, several authors (Citation17–Citation20) have proposed that machismo can be expressed differently in different men, with their behavior oscillating within a continuum of positive and negative characteristics. In a quantitative study of Latino men living in the United States, five different types of machismo were identified: contemporary masculinity, machismo, traditional machismo, compassionate machismo, and contemporary machismo (Citation18). These types differed in key characteristics such as whether or not they were authoritarian, the degree of demands regarding women's obedience, different levels of competitiveness, and, most important, different degrees of flexibility regarding traditional gender relations.

In a review of studies exploring masculinities in Latin America, Gutmann (Citation21) also highlights the multiplicity of masculinities in this region. This diversity has been documented in Mexico by Ramirez Rodriguez (Citation22), who found that young men's attitudes toward gender relations can range from conservative to ambiguous to flexible. Gutmann (Citation21) proposes that Latin American masculinities have been in a process of change, suggesting that these transitions have been influenced by global economic changes that have led to increasing modernization and urbanization, new job markets for women, and a growing feminist activism in the region. These changing patterns of masculinity may also have been influenced by ongoing interventions in a number of Latin American countries, such as Program H in Brazil, which have been actively promoting more gender-equitable forms of masculinities (Citation23–Citation26).

Why is it important to challenge hegemonic masculinities?

Young people's health is often influenced by gender inequalities – one example is access to contraception – and these are reinforced by unequal gender relations present in hegemonic masculinities. Thus, challenging hegemony and hence the gender order might improve the health of young people. The World Health Organization defines gender equality as the ‘the absence of discrimination – on the basis of a person's sex – in providing opportunities, in allocating resources and benefits or in access to services’ (Citation27). Achieving gender equity – ‘fairness and justice in the distribution of benefits and responsibilities between women and men’ (Citation27) – is a critical step in the process of attaining gender equality. It has been argued that men are the main guarantors of the patriarchal gender order (Citation28); thus, several researchers have pointed out that interventions aiming to achieve gender equity must involve men in order to be more successful (Citation24, Citation28, Citation29). Around the world, different cultural constructions of masculinities have been associated with men's unhealthy behaviors, such as aggression and risk taking, leading to a higher risk of morbidity and mortality over men's life course (Citation30, Citation31). Young men often feel pressured by society (Citation32, Citation33) to engage in these behaviors to prove their masculinity to themselves and their peers (Citation30, Citation34–Citation36). Women's health is affected by men's negative behaviors. One significant example of this is men's violence against women (VAW), a common expression of male power and control in patriarchal societies (Citation37). VAW is a widespread public health problem affecting women throughout their life span (Citation38). Recent population-based data suggest that one form of VAW – intimate partner violence (IPV) – is a transcultural phenomenon, including physical, sexual, and psychological violence and affecting women and families worldwide, especially those in low-income countries (Citation39). Exposure to IPV has consistently been associated with women's poor mental, physical, and reproductive health (Citation40, Citation41).

Rationale for this study

In Nicaragua, studies have found evidence of changing gender norms in both women (Citation42) and men (Citation43, Citation44). In a qualitative study of adult men, Sternberg et al. (Citation43) reported that men had different discourses about masculinity, ranging from a traditional patriarchal stance to a feminist discourse. Welsh (Citation44) proposed that men's attitudes toward more equal gender relations might be linked to their participation in activities aimed at challenging patriarchy in this setting. Quantitative and qualitative studies describing the changes that adult and young men experienced while engaging with institutions promoting changes in masculinity patterns have been conducted in Latin America and around the world (Citation21, Citation26, Citation43 Citation45 Citation46). However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have explored in full how these changes happened, what influenced the flow of these pathways of change, and what forms of masculinities emerged from this process. The purpose of the present paper is therefore twofold: (i) to explore notions of various forms of masculinities among young Nicaraguan men participating in training programs addressing sexual health, reproductive health, and/or gender equality and (ii) to find out how these young men perceive their participation and involvement in actions aimed at reducing VAW.

Methods

Setting

The study was performed in Managua and León municipalities, Nicaragua. Nicaragua is a low-income country with high unemployment. As in other low-income countries, young people face many challenges, with poverty and lack of educational opportunities the most prominent. National data show that only 39% of those attending high school complete their education (Citation47). In addition, both the public and the private school system lack a scientific and progressive sex education program.

The hegemonic pattern of masculinity in Nicaragua is machismo. Machismo is understood as the set of attitudes and behaviors that dictate how men interact with women and with other men. According to Welsh et al. (Citation48) and Lancaster (Citation49), machismo is based on the notion that men are superior to women and that men are tough, violent, domineering, and womanizers. Conversely, marianismo is a form of emphasized femininity that reinforces machismo. It promotes the ideal that ‘real women’ are docile and compliant to men's patriarchal privileges (Citation16). Several studies conducted in Nicaragua have shown that machismo strongly influences young men's behaviors, increasing health risks both to themselves and their partners (Citation44, Citation50). For example, quantitative studies have shown that young Nicaraguan men, despite growing knowledge of how HIV can be transmitted, use condoms inconsistently and mainly with occasional partners (Citation51, Citation52), leaving their stable partners unprotected against the possible risk of sexually transmitted diseases and HIV. Traditional machismo behavior includes promiscuity and has been associated with their female partner's higher risk of developing high grade cervical lesions (Citation53).

The Nicaraguan government has an ambiguous position on gender and sexual and reproductive rights. Although it has increased the availability of resources to diminish maternal mortality, access to therapeutic abortions was criminalized for the first time in the last 100 years. In addition, despite the fact that Nicaragua is a signatory of The Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women, changes in the country's legislation and special units at police stations to handle VAW, it continues to be a serious public health issue. According to the most recent national survey, 21% of women reported being exposed to emotional, physical, or sexual abuse by their partners in the past year (Citation54). In addition, a recent study found that 15% of ever-pregnant Nicaraguan women had experienced physical abuse in the past year and 24% reported a continuous pattern of abuse (Citation42).

Population-based studies have been conducted, among women but not among men, assessing their attitudes to gender relations and VAW (Citation42, Citation54). A recent 4-year panel study showed that there has been a significant change in women's attitudes toward VAW and gender relations. Nicaraguan women have become less tolerant of partner abuse and less supportive of traditional gender relations (Citation42). In addition, a qualitative study among men found that feminist and patriarchal discourses about masculinity coexist in Nicaraguan society (Citation43).

Thus, machismo behaviors and traditional norms have not gone unchallenged in Nicaragua. Although the government has not implemented any systematic counter-machismo programs, over the last 20 years, the strong civil society of Nicaragua and its non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as Cantera (Citation24, Citation44), CISAS (Citation45), and Puntos de Encuentro (Citation55) among others, have implemented grass-roots and population-based interventions aiming to challenge and change patriarchal behaviors and values among young people. Many of these interventions have been implemented from a feminist perspective (Citation44). One recent example is a community-based intervention directed at young people and conducted by the NGO Puntos de Encuentro. This intervention included training workshops, educational materials, and mass media activities (a radio show and a soap opera). The activities aimed to challenge norms about HIV, masculinity, and VAW. The soap opera was broadcasted on national TV (Citation55).

Data collection and participants

We gathered the data through six focus group discussions (FGDs) and two in-depth interviews. The sampling was purposive in accordance with the flow of the emerging concepts. We contacted the participants through NGOs working with young men in two of the main Nicaraguan cities (Managua and León). The NGOs were in general addressing broad topics within a gender, VAW, reproductive, and sexual health framework. Their activities were heterogeneous and varied from group education, community outreach, and mobilization to a combination of these methods. The activities seemed to depend on the NGOs’ own agendas (Citation24).

Three focus groups were conducted in Managua and three in León. The participants in each group belonged to the same NGO and thus knew one another. The facilitator encouraged them to discuss with each other rather than directly answering the questions. The focus groups had on average 10 participants and met in a private room to avoid outside disturbance and ensure confidentiality. As part of the emergent design, during the analysis and interpretation of the data, we also performed two in-depth interviews. In the course of the analysis of the FGDs, we started to identify the different masculinities emerging from the data and how they related to each other. The in-depth interviews allowed us to confirm and deepen our understanding of the differences and similarities between the masculinities identified from the FGDs, as well as the ways these masculinities were constructed.

In total, we gathered data from 62 young men who were participating voluntarily in NGO training programs. Their involvement with the NGO programs occurred as follows: some were recruited directly by the NGO's facilitators in the neighborhoods where the interventions were taking place, while others had been invited by friends who were already members. The young men expressed various motives for joining an NGO. Most wanted to learn more about sexual and reproductive health, some wanted to spend time with their friends, and others were curious about the NGO's activities. The participants’ age ranged from 17 to 24 years and their educational level from incomplete high school to some university education. Most of the participants were studying and some were working in the informal sector.

The participants’ length of involvement with an NGO varied from 1 to 4 years. During this period, their exposure to the NGO's activities was highly heterogeneous, even within groups. The young men were exposed to different educational sessions, each lasting from 1 to 3 months. During this time, they also participated in other NGOs’ activities, such as rallies, theater presentations, and so on. We consider this an advantage rather than a disadvantage, as the heterogeneous sample allowed us to identify the similarities and differences between informants’ experiences.

In the FGDs, very few participants spontaneously identified themselves as homosexual or bisexual. The FGDs and the interviews lasted between 60 and 150 min and were conducted in Spanish. An audio device was used to record the data, which were subsequently transcribed verbatim.

For both the focus groups and the in-depth interviews, we used a semistructured discussion guide with open-ended questions to explore the participants’ perceptions of their training experience, masculinity, gender relations, and VAW (). The discussion guide was developed by the researchers as a part of a larger project exploring masculinities in Latin America and was adapted to the Nicaraguan context. To explore informants’ attitudes toward gender relations, we used hypothetical questions (Citation56) such as: Someone once told me that a good wife must obey her husband even if she doesn't agree with him. What do you think? From this statement, we then asked participants to reflect on and discuss issues of gender and violence. These questions were modified from those used by the WHO multicountry study on women's health and domestic VAW in the section on attitudes toward gender roles (Citation57).

Table 1. Semistructured interview guide

In addition, to explore informants’ specific attitudes toward VAW, we used short oral vignettes (Citation58) describing situations in which women were experiencing IPV and sexual abuse. For example, we used the following vignette to explore the participants’ attitudes toward IPV:

Johana is 20 years old. She has been Ruben's girlfriend for the last three years. Ruben has been acting very jealously lately, yelling and insulting her every time she says hello to a friend. The last time, he hit her when they got home. What do you think about this? Why?

Follow-up, probing, and interpretative questions were employed to further explore topics that emerged from the data (Citation56). The emergent design of our study also allowed us to include new topics that arose from the previous discussions in the subsequent FGDs and interviews.

Analysis

We analyzed the rich data gathered from the focus groups and interviews using the grounded theory method of constant comparison (Citation59). We used this method because we understand reality as socially constructed (Citation60); thus, we aimed to build theory emerging from the data rather than from a preconceived hypothesis. The data collection and analysis were conducted in parallel, so-called abduction. The analytical process started with a sentence-by-sentence open coding that helped us to identify concepts and actions that described the informant's experience (Citation61). The open coding was conducted using OpenCode 3.4, a free software program developed by Umeå University (Citation62). We then performed selective coding. This means that open codes that had something in common were grouped together, forming categories, thus representing a higher level of abstraction. During this process, a core category emerged, and its properties and dimensions were identified. Finally, we created a model grounded in the data that represented how the categories related to each other, a step called theoretical coding (Citation63).

Ethical considerations

The research protocol was approved by the Faculty of Medicine Ethical Committee of the National Nicaraguan Autonomous University, León. Participation in the research project was voluntary. We obtained oral informed consent before starting to collect the data and before recording the FGDs and interviews. All participants were informed about the objectives of the study and that they could withdraw from participation at anytime.

Results

In the following section, we present an overview of the main findings. We then describe the core category in depth, the subcategories/ideal types and their properties and dimensions, and the factors shaping the core category. Constant comparison of the data allowed us to identify a core category representing the process of change in gender relations and masculinity among organized young Nicaraguan men and the individual and external factors facilitating or constraining this process (). This core category, labeled ‘Expanding your mind’, contains four subcategories representing the changing masculinities that emerged through the process (The apprentice, The responsible/respectful man, The proactive peer educator, and ‘The feminist man’). Following Max Weber, the subcategories are constructed as ideal types (Citation64), which aim to capture the principal characteristics of the identified emergent masculinities. They should be understood as joint abstractions of the ideas and attitudes presented by the young men, and do not represent any particular man, rather summarize notions from several men in the different FGDs and interviews. The model also conceptualizes how the subcategories relate to each other.

Fig. 1. ‘Expanding your mind’: the process of constructing masculinities in young Nicaraguan men participating in training programs and the individual and social factors facilitating or constraining this process.

The grounded theory analysis allowed us to identify seven properties of the process with their respective dimensions. These properties are the degrees of awareness, respectfulness, and responsibility, and the development of a critical stance, political stance, thoughtful actions, and agency. shows the properties listed according to the subcategory/ideal type where they were first identified. However, it is important to highlight that properties and dimensions cut across more than one subcategory. This is clearly evident in those subcategories emerging at the end of the process of change.

Table 2. Properties and dimensions of the core category ‘Expanding your mind’a

‘Expanding your mind’

The apprentice: increasing individual awareness

This subcategory arose from the young men's perceptions of their positions in their initial engagement with groups offering training in sexual and reproductive health and/or gender. During this period, awareness emerged as an important property of the process. Its dimension ranged from being unaware to becoming more conscious about reproductive health risks and gender inequalities. Awareness was described as ‘opening your eyes’. This process implied not only an increase in knowledge but also an increased awareness on the part of the young man of the consequences of his own actions, an expanded assessment of the risks of being sexually active (such as unintended pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases), and a growing consciousness of the negative consequences of machismo and VAW for men and women.

The data analysis revealed that this subcategory was defined by two concomitant actions: learning and reflection. For The apprentice, learning meant that his continued exposure to the training allowed him to gradually acquire scientific knowledge on several issues previously considered taboo, such as sexuality, methods of contraception, sexually transmitted diseases, and HIV. Depending on the content of the training program, he might also begin to be exposed to concepts such as gender equity and/or VAW prevention. Exposure to this new information and the debates triggered by it in his interactions with other young men in the group seemed to facilitate a cognitive change, enabling The apprentice to begin to reflect upon his own experiences, behavior, and attitudes toward others, as well as the social context in which he interacted.

This training has helped to open my eyes to many things: to HIV, to what it can do to you, how you can get it … I've also learned about gender equity, about sexuality, how to take care of your sexuality … So it has helped to open my eyes. (FGD 6)

Nevertheless, for The apprentice, the process of learning and reflecting on his life experiences was perceived as difficult: an internal struggle to confront internalized machismo and homophobia. Challenging the burden of traditional gender relations seemed initially more complex than the lack of reproductive health knowledge. Gender equality was perceived as difficult to grasp because it represented a contrary set of values to those the young man had learned from his environment.

Getting to grips with gender equality was a little difficult for me … for me it was difficult to realize that men in our society are machistas and then … that men and women have the same rights and the same opportunities … it was very difficult because I had learnt something different at home … that women made the food and the men sat around … it was like … in my house they say one thing and here something else. (FGD 5)

VAW was often normalized. Blaming women for the violence they experienced from their partners was common and often understood as they ‘consented’ to it. The apprentice often felt that ending IPV was mainly the woman's responsibility.

The responsible/respectful man: thinking before acting

The responsible/respectful man emerged as a consequence of the reflecting process initiated by The apprentice. Young men's perceptions of their own cognitive and behavioral transformation represented the first challenge to machismo and constitute the foundations for this subcategory. The properties identified in this subcategory (responsibility, thoughtful action, and respectfulness) represent the identified behavioral and cognitive transformations. The dimensions outline how The responsible/respectful man perceived himself as following a journey from irresponsibility to greater trustworthiness, from impulsiveness to thoughtfulness about his own behavior, and from intolerance to greater acceptance of others’ ideas and behavior. These properties might represent the informants’ first steps in shifting gender relations toward a more empathic and considerate stance regarding the needs and rights of others around them.

The responsible/respectful man perceived this period as a time of transformation, with the concept of growing into manhood strongly emerging from the data. This growing process was strongly associated with ‘walking the talk’, meaning putting into practice the knowledge the participant had previously acquired. A key cognitive change was that the participant began to assume responsibility for his own actions, especially regarding his sexuality – for example, a more responsible sexual behavior that challenged indiscriminate sexual contacts as a sign of manhood and that included pregnancy prevention and condom use during sexual intercourse.

To me, being a man means being faithful to your wife. I don't believe that having a lot of women means you are a man, I think it means you're a machista. To me, being a man means having only one woman, supporting your kids, giving them love and support, helping them anyway you can. (FGD 2)

In addition, the concept of thoughtful action emerged as a significant finding from the data. The responsible/respectful man recognized that he was dissimilar to his peers, i.e. that he behaved differently from ‘regular guys’. He also clearly recognized how his decision-making pathway was different from other young men not engaged in gender or reproductive health training – because he did not act on impulse. Thoughtful action for him meant ‘thinking before acting’, taking into account the consequences of his acts before choosing how to behave.

I think that what makes us different to other men is that they haven't had the information we have … we are conscious of what we're doing. We are conscious of the harm we can inflict; basically you have to be aware of your own actions and give your best to all humanity, because we are human, too, and you can hurt yourself as well … You have to think twice before doing something. (FGD 1)

The constant comparison of the data enabled us to identify other significant cognitive changes in this phase. Growing into a man meant ‘opening your mind’, a process of becoming more respectful and tolerant of other people's ideas, of women, and of sexual options other than heterosexuality. However, this transition did not seem to be complete. Although The responsible/respectful man claimed to be more open, homophobia, machismo, and heteronormativity persisted to some degree. In addition, The responsible/respectful man often expressed an ambiguous stance regarding traditional gender relations and VAW. Even though he expressed attitudes rejecting IPV and sexual abuse, partner abuse was still perceived as a private issue, and men's sexual harassment of women was somehow tolerated if it was unclear whether the situation implied the woman's consent or not. The responsible/respectful man was in two minds about how to react to IPV and sexual abuse: he mostly felt that his involvement would serve no purpose and not end the abuse and thus felt uncomfortable getting involved.

The proactive peer educator: empowering others

This subcategory/ideal type represents the transition from an individual, focused on his own cognitive and behavioral change, to a young man more focused on empowering others by promoting cognitive and behavioral change in his peers. The proactive peer educator's focus on action allows us to identify agency as an emergent property of this subcategory, with its dimension moving from passivity to action.

The proactive peer educator represents a young man who influences others by sharing his knowledge on reproductive/sexual health and gender. He aims to help other young people avoid the negative consequences of unsafe sexual behavior, such as unintended pregnancies, sexually transmitted disease, and HIV. However, sharing knowledge was not the only action defining The proactive peer educator. Passing on new values to his peers was also mentioned as an important part of the process of helping others to reflect on their own behavior and on how that behavior had been influenced by machismo. Key values that The proactive peer educator strived to promote were respect for other people's views, respect for women, and gender equity. The process of empowering others seemed also to boost The proactive peer educator's self-esteem, generating feelings of pride:

This training has helped me to learn many things about sexuality, about HIV, about gender equity, the meaning of sexuality … This experience has helped me remove the blinkers we were wearing, and it has helped us to remove other people's blinkers … Because the objective is not to keep the things you've learned to yourself but to disseminate the information to others. (FGD 4)

In addition, The proactive peer educator expressed a more positive attitude toward getting involved in the process of ending IPV and sexual abuse. However, ambivalence toward intervention persisted. The concept of conditional intervention emerged, influencing his actions to end abuse. His choices regarding actions to end violence appeared to depend on the severity of the abuse, the closeness to the victim, and concerns about his own safety. Providing emotional support, informing women about their rights, advising them to seek help, and promoting attitudinal change in the abusive man were the most common types of interventions described. In cases where the relationship with the victim was closer (e.g. friends and family members), The proactive peer educator seemed to be more willing to advise the woman to go to the police, call the police himself, or even to intervene physically to halt the violence.

Well, if she (a victim of IPV) was my friend, I'd advise her to leave, but if she was my sister … boy, if a guy hit my sister he'd be in serious trouble, because I'd hit him back … that's for sure! (Interview N.1)

‘The feminist man’: advocating social change

The prominent feature of this subcategory is that ‘The feminist man’ strives to promote change not only at the individual level but also at societal level. This meant developing an analytical and critical stance to his social context, a key property of this phase, whose dimension signified a journey from an incipient to a developed critique of the gender order in Nicaragua. In addition, it implied assuming a political stance, another property, whose dimension represented a shifting from conformist to vigorously opposing the gender order. This subcategory was named ‘The feminist man’ because some young men spontaneously identified themselves as such.

Critical analysis of the social context allowed ‘The feminist man’ to begin to identify the inequities of gender relations (e.g. women's economic dependency) and to become more empathic toward women and lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and transgenders (LGTB). These reflections on the gender order influenced a cognitive change toward challenging and rejecting heteronormativity, traditional gender norms on homosexuality, and traditional gender relations:

Being machista is not cool. We are feminists because it is the opposite of being machistas … We recognize that men and women must have equal status in society, and that neither gender should be superior to the other … We believe that both sexes are equal and that machismo is a conduct learned in this patriarchal society. (FGD 3)

In addition, ‘The feminist man’ strongly rejected men's controlling behavior, unsafe sexual behavior, and hypersexuality as signs of masculinity. This meant that he started to experience a change in his own gender relations, performing actions traditionally deemed feminine, such as cooking and laundry. ‘The feminist man’ also experienced an important emotional turning point: he felt comfortable with his own sexuality and comfortable showing emotions and affection to others.

Declaring a political stance against traditional gender relations and VAW emerges as another key characteristic of ‘The feminist man.’ This young man perceives himself as different because he recognizes women's, gay, lesbian, and transsexual rights and autonomy. Thus, he assumes a political stance toward promoting and defending those values and rights. Regarding VAW, he felt frustrated about what he perceived as some women's submissive behavior to men and their silence and passivity in the face of IPV. These perceived attitudes and behaviors were among the most contested and criticized gender relations between men and women.

A key difference between The proactive peer educator and ‘The feminist man’ was that the latter rejected VAW in all circumstances and was more likely to get involved in actions to prevent or end the abuse regardless of whether he was acquainted with the victim or not. He clearly recognized VAW as a public rather than a private issue. This does not mean that The Proactive peer educator and ‘Feminist man’ subcategories/ideal types are opposites: they are defined not only by the focus of their actions but also by the way they think about gender relations and their level of political involvement in promoting more gender-equitable rights. The proactive peer educator might become a ‘Feminist man’ if critical thinking and reflection about the societal gender order are an important part of his process of change. Conversely, ‘The feminist man’ can also conduct peer education in sexual and reproductive health if required. The arrows in the model show the variability in subjects’ positions.

Factors facilitating or constraining the process

The rich data show that external and individual factors interacted with the core category, ‘Expanding your mind,’ influencing its course. Peer and family pressure to conform to traditional norms and values emerged from the data as strong external factors hindering the process. Fear of rejection and discrimination, generated by the strongly critical environment the young man faced, hindered his cognitive and behavioral transition. However, as he moved along the process, he began to develop coping skills to deal with the stigma and discrimination that was generated by confronting his peers and his community with his new beliefs and behaviors.

I think I'm different to my friends … They say I act too defensively when they talk about women. When I hear them talking about mistreating women, or when they make nasty sexual comments about their girlfriends, I usually tell them … Hey, don't talk like that; remember that a woman gave birth to you and now you are insulting them (women) … sometimes they get mad and call me a faggot, gay, homosexual … And I tell them, why am I a faggot? Just because I defend women, just because I am conscious that you don't have to treat women like that? (FGD 4)

We identified that belonging to a group that shared the same gender-equitable values and behaviors was an important external factor facilitating the transition. This allowed the participant to receive group support and reinforcement of his behavioral and cognitive change, which proved to be a significant and necessary factor to sustain his new stance toward gender relations.

When I joined the group, people had started to say that I was gay just because I had started to think differently … In the group we always talk about how to overcome those criticisms. (FGD 2)

Discussion

The main findings of this study show that our informants experienced a process of change labeled ‘Expanding your mind.’ This represents a gradual transition from values and behaviors rooted in traditional gender norms and masculinity to forms of masculinities that challenge norms that justify VAW and that promote healthy sexual and reproductive behaviors and gender-equitable attitudes. The process also shows how an increased awareness of gender inequities facilitated the emergence of values (respect and responsibility) and behavior (thoughtful action) that contributed to increase the informant's critical thinking and agency at an individual, social, and political level. The flow and direction of the process was influenced by individual and external factors facilitating or constraining it.

‘Expanding your mind’: the process of change

To our informants, going through the process implied a series of personal transformations. However, this process should not be understood as linear: the different subcategories/ideal types are not static and the young men moved between them as they journeyed through their process of change. Many researchers, around the world (Citation2, Citation4, Citation8, Citation10, Citation13) and in Latin America (Citation17–Citation19, Citation21, Citation22), have pointed out the many types of masculinity and its relational characteristic in the general population. Connell has stated that gender relations are dynamic entities that can evolve by the pressure of men and women challenging them (Citation4). Our results show that this transition is possible and that multiple progressive intertwined masculinities can emerge from the process of change in young men engaged in gender and reproductive health programs.

The process that emerged from the data showed a positive transformation regarding norms and values relating to gender relations. This transition has been identified by Connell as an important sign of changing masculinities (Citation65). In addition, we concur with Howson that protest femininities are important factors shaping masculinities around the world (Citation7). The process of change among the participants was clearly promoted and facilitated by the rising protest femininity movements in Nicaragua (Citation44) related to the growing feminist agenda in Latin America (Citation21).

In the last 20 years, with the aim to challenge traditional patriarchal norms, several NGOs around the world have conducted activities with adult and young men (Citation23, Citation24, Citation26, Citation46, Citation55, Citation66). Many of these NGOs have documented changes in norms, attitudes, and behaviors in their target populations (Citation26, Citation46, Citation55, Citation66). However, the majority of these reports did not examine the process of change their target populations experienced in-depth. We were able to identify only one published study describing the pathways that men followed in their involvement in activities against VAW, and this was from the United States (Citation67). To the best of our knowledge, ours is one of the first qualitative studies to explore the process of change in young men participating in activities aimed at challenging patriarchy in Latin America.

The properties and dimensions of the core category process cut across the ideal types and represent the behavioral and cognitive changes identified. Thus, in the following discussion, rather than discussing the ideal types we address the process of change by discussing the properties and dimensions that emerged from the grounded theory analysis.

Awareness, responsibility, and thoughtful action

Hegemonic masculinities often affect young men's health by encouraging risk-taking and unsafe sexual behavior (Citation32, Citation33), and studies confirm that Nicaraguan young men are not an exception (Citation50–Citation52). Our results show that young men participating in reproductive health and/or gender equality programs experienced an increased awareness of how machismo(s) shaped their gender relations and how these unequal gender relations affected both women's and their own health. This was more evident during the initial part of the change process, where participants developed emergent masculinities that started to exhibit positive attitudes and behaviors toward a more responsible sexual and reproductive conduct. These positive changes mirror the findings of studies conducted in other low-income countries (Citation46, Citation66, Citation68) as well as in Nicaragua (Citation44), assessing the effectiveness of gender and reproductive health programs in changing young men's attitudes and behaviors toward sexuality and reproduction.

Being a responsible man has been part of the different expressions of hegemonic masculinities in Latin America. It has mainly been associated with being the breadwinner for one's family and policing family members’ behavior (Citation17, Citation18, Citation22, Citation45, Citation49). We argue that the concept of responsibility that emerges from the process that our informants experienced is different from the dominative principle expressed by the hegemonic patterns of masculinities (Citation7). The concept expressed by our informants focuses more on increasing their accountability for their own behaviors and less on becoming their family's breadwinner. Increasing young men's accountability for their own behaviors has been identified as a key attitudinal change in the process of achieving more gender-equitable and non-violent masculinities (Citation29). Developing new values such as responsibility facilitated the emergence of the property of thoughtful action, constructed in opposition to impulsivity, a behavior that our participants strongly associated with traditional machismo(s). This property is very similar to what Weber, cited in Hughes et al., defines as ‘value rational action’ (Citation69), in which people's actions are influenced by their own values rather than the benefits they can obtain from them.

Respect and ambiguity

As the young men moved along the process, they seem to have modified their gender relations, expressing more gender-equitable attitudes and behaviors that challenged traditional power relations between men and women, homophobia, and VAW. Respect emerged as a key property behind these changes, emphasizing tolerance toward other people's views and sexual practices. This also implied that participants gradually developed a more empathic stance toward the needs and rights of women and subordinated masculinities (Citation1, Citation2). The concept of respect emphasized by our informants is quite different from the meaning constructed by hegemonic masculinities and traditional machismo(s) in Latin America, which associate respect with authoritarianism and obedience to the male head of the household (Citation7, Citation17, Citation18).

Although respect is a key property of the process of change, it is important to emphasize that this attitudinal and cognitive transition developed gradually, and where some forms of emergent masculinities – The apprentice, The responsible/respectful man, and The proactive peer educator – showed an ambiguous stance toward subordinated masculinities and VAW. This is in line with the findings of Pulerwitz et al. (Citation26), showing that inequitable and equitable attitudes can coexist in young men receiving gender training and that, as illustrated in one Mexican study, some patriarchal attitudes are more easily changed than others (Citation22).

This ambiguity can clearly be recognized in the participants’ perceptions of their own involvement in actions aimed at preventing or ending VAW. Latané and Darley (Citation70) and, more recently, Casey and Ohler (Citation71), using a bystander model, identified that intervening to prevent or stop VAW is a complex process that goes from identifying the violence to assuming personal responsibility to implementing the selected actions. In addition, they identified that men's choices of strategy to end or prevent the VAW are influenced by contextual and individual factors. Bystander model by Casey and Ohler (Citation71) clearly fits our informants’ experiences. Their disapproval of VAW and willingness to prevent or deter it increased as they moved along the process of change. However, their choice of action or inaction was conditioned by their perception of the severity of the abuse, concerns for their own safety, and their closeness to the victim, which is in line with the factors reported by Casey and Ohler (Citation71).

Our informants’ reactions to VAW can also be explained within the manhood acts theoretical framework, which focuses on the actions that men do to differentiate themselves from women (Citation12). Schrock and Schwalbe suggest that manhood acts can vary according to situation. One such situation is when men refuse to act as the hegemonic masculinity ideal dictates (Citation12), and this seems to be the case depicted in our informants’ process of change. It is important to stress that even if the informant's choice of strategies to end or prevent VAW was mainly based on non-confrontation, the masculinities that emerged at the end of the process (The proactive peer educator and ‘The feminist man’) were more inclined to action rather than passively standing by.

Agency, empowerment, critical thinking, and political stance

Involving men in actions aiming to improve gender equality in health has been described as a key strategy to achieve successful results (Citation28, Citation46). Broido has proposed that men, as members of the dominant social group, can become important allies in the process of ending the unequal gender order (Citation72). Our results suggest that the progressive masculinities identified at the end of our informants’ process of change, The proactive peer educator and ‘The feminist man,’ are crucial allies in the struggle to change the current gender order.

The proactive peer educator and ‘The feminist man’ represent empowered forms of masculinity in the sense that they increased their self-esteem, expanded their ability to take action, and developed agency to achieve their desired results (Citation73, Citation74). In addition, both masculinities aimed to fight gender inequality by openly criticizing other young men's oppressive manhood acts (Citation12). However, they also show important differences. The proactive peer educator masculinity does not seem to have the same level of critical stance toward the gender order and political commitment to challenge patriarchy as ‘The feminist man.’ Another key difference is that ‘The feminist man’ clearly opposes marianismo (Citation16), the emphasized femininity (Citation7) in Latin America that promotes a female ideal as docile and compliant to men as well as the privileges that the gender order bestows to complicit masculinities (Citation2, Citation71). We found that our emergent concept, ‘The feminist man,’ is similar to what Pulerwitz and Barker (Citation68) have defined as the ‘Gender equitable man’. This is a man who strives to have equitable gender relations based on respect, non-violence, and tolerance for sexual options other than heterosexuality.

A possible reason for the differences between The proactive peer educator and ‘The feminist man’ could be the diverse focus of the educational activities they have been exposed to. There might be significant variation in how gender and masculinities are approached within these activities (Citation46, Citation75). In our study, the NGOs’ activities were highly heterogeneous; thus, it was not possible to clearly identify how gender issues were approached and how these influenced the identified masculinities. Further studies are needed to assess whether the focus of the various NGOs’ activities influenced the masculinities that emerged from the young men's processes of change.

Individual and social factors facilitating or constraining the process of change

As reported by other researchers, social pressure to adhere to the traditional patriarchal norms and internalized machismo are the most important factors influencing young men's behaviors toward sexuality and gender (Citation32–Citation34) and constraining the process. However, belonging to a group that shared the same gender-equitable values was a key factor reinforcing our informants’ process of change. It provided them with a safe place to reflect upon gender and to build a network of peers who supported and encouraged their new subject position on traditional gender values and behaviors. This is in line with the findings of several researchers pointing to the key role of group membership in facilitating and maintaining individual cognitive and behavioral change (Citation22, Citation25, Citation26, Citation28, Citation29,Citation67).

Limitations and strengths

A qualitative study aims to explore and understand informants’ experiences in depth. According to Marshall (Citation76), the optimum sample size for a qualitative study is ‘one that adequately answers the research question’. We found that the data collected from our 62 informants (divided into six focus groups and two in-depth interviews) provided sufficient information to answer our research question. This means that we collected data until no new information relating to our research question emerged, thus reaching saturation. Although our sample size might be small for a quantitative study, it is sufficient for a qualitative study in which our aim is to illuminate the transformation process experienced by the informants. With our results, our aim is for theoretical rather than statistical generalization (Citation63, Citation77).

In grounded theory, models are constructed using an abductive method – that is, generating theory that is rooted in the data and then continuously testing that theory with new informants (Citation61). By applying this method, we found that the informants recognized that they had experienced a process of change. One possible criticism of our model is that it appears to describe a linear process of change. To our informants, going through the process implied a series of personal transformations. We argue that this process is not the same for all young men; we cannot prove exactly where in the suggested process they were when each individual started. We conclude that they have a number of common starting points but can develop different progressive masculinities depending on the influence of individual and external factors.

A limitation of this study is that we cannot explore whether the cognitive and behavioral changes reported by our informants will persist once they have ceased their interaction with the NGOs. They might revert to their preintervention attitudes and behaviors (Citation24, Citation29, Citation66). However, a number of authors have argued that young men who have been involved in activities where they were engaged in reflecting critically about the gender order and masculinity and those who have a political stance are more likely to maintain their cognitive and behavioral change (Citation25, Citation29, Citation78).

Social desirability bias is a risk when conducting any kind of research, especially when trying to portray change. To reduce this bias, we used several strategies during data collection, for instance, vignettes to encourage discussion of sensitive issues. This allowed us to collect the group participants’ different attitudes toward VAW and gender topics. Further, we used follow-up and probing questions to gain a deeper understanding of the issues raised during the group discussions or interviews and to encourage discussion among the focus group participants. During the whole process, we acted in a non-judgmental manner, encouraging informants to speak freely; we also emphasized that there were no right or wrong statements.

We aimed to increase the credibility of our findings by constructing a team of researchers with different theoretical backgrounds – such as public health, medical sociology, and gender studies – to analyze the data (Citation77). Information was gathered using different data collection methods, a technique known as triangulation. Further, we conducted a ‘peer-debriefing’ session, a technique that consists of discussing our findings with other colleagues not involved in the analysis of the data (Citation77).

Conclusions

Our results show that multiple progressive masculinities can emerge from activities challenging traditional masculinity in this Latin American setting. Developing gender-equitable attitudes and behaviors is experienced as a process involving not only acquisition of information but also developing respect for other people's views and sexual choices, assuming responsibility for one's own sexual behavior, and learning and applying new skills such as agency, critical thinking, and a political stance.

The emergent masculinities identified in this study show a range of attitudes and behaviors; however, all lean toward more equitable gender relations. It is important to highlight that changes in gender relations were identified not only between genders but also within a gender. The masculinities that developed at the end of the process showed greater tolerance and respect toward men who have sex with other men, also termed subordinated masculinities in the construction of hegemonic masculinities. In addition, the emerging masculinities identified aimed to build relationships of mentorship and leadership with other men rather than ones of subordination, complicity, or marginalization.

Clearly, the masculinities that emerged during the informants’ processes of change can be health promoting, facilitating the empowerment of other young men and women. However, the results suggest that learning about sexual and reproductive health does not directly imply developing more gender-equitable attitudes and behaviors or a greater willingness to prevent VAW. It is paramount that institutions working with young men consider their strategic as well as their practical interest during the planning stage of activities targeting this population. Activities that aim to challenge machismo in this setting must continue and be expanded to reach more young men. Including discussion of gender equity, masculinity, and VAW in the curricula of the public education system might be an important way to reach more young men. As stated above, further studies are needed to deepen our knowledge of how the masculinities that emerged from the informants’ processes of change are influenced by the focus of the various NGOs’ activities.

Conflict of interest and funding

The authors declare that they do not have any competing interests.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the institutions and participants who shared their histories and time with us. We also wish to thank all members of Theme IV ‘Gender and Health’ and Kjerstin Dahlblom at Epidemiology and Global Health, Umeå University, for their comments and suggestions on earlier versions of this manuscript. Finally, we wish to thank the Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine, Umeå University, and the Umeå Center for Gender Studies for financial support.

References

- Connell RW. Gender2nd ed. Polity Press. Cambridge, 2009

- Conell RW. Masculinities2nd ed. University of California Press. Los Angeles CA, 2005

- Walby S. Theorising patriarchy. Sociology. 1989; 23: 213–34. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Connell RW, Messerschmidt JW. Hegemonic masculinity: rethinking the concept. Gend Soc. 2005; 19: 829–59. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Demetriou D. Connell's concept of hegemonic masculinity: a critique. Theory Soc. 2001; 30: 337–61. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Hirose A, Kei-ho Pih K. Men who strike and men who submit: hegemonic and marginalized masculinities in mixed martial arts. Men Masc. 2010; 13: 190–209. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Howson R. Challenging hegemonic masculinity. Routledge. London and New York, 2006

- Kimmel M. Global masculinities: restoration and resistance. A man's world? Changing men's practices in a globalized world. Pease B, Pringle KZed Books. London, 2001; 21–27.

- Dernés S. Globalization and the reconstitution of local gender arrangements. Men Masc. 2002; 5: 144–64. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Beasley C. Rethinking hegemonic masculinity in a globalizing world. Men Masc. 2008; 11: 86–103. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Ruspini E, Hearn J, Pease B, Pringle K. Introduction. Men and masculinities around the world: transforming men's practices. Ruspini E, Hearn J, Pease B, Pringle KPalgrave MacMillan. New York, 2011; 1–16.

- Schrock D, Schwalbe M. Men, masculinity, and manhood acts. Annu Rev Sociol. 2009; 35: 277–95. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Whitehead SM. Men and masculinities. Key themes and new directions. Polity. CambridgeUK, 2002

- Hearn J. From hegemonic masculinity to the hegemony of men. Feminist Theory. 2004; 5: 49–72. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Martin PY. Review: why can't a man be more like a woman? Reflections on Connell's masculinities. Gend Soc. 1998; 12: 472–4. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Stevens EP. Machismo and marianismo. Society. 1973; 10: 57.10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Stobbe L. Doing machismo: legitimating speech acts as a selection discourse. Gend Work Organ. 2005; 12: 105–23. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Torres JB, Solberg VSH, Carlstrom AH. The myth of sameness among Latino men and their machismo. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2002; 72: 163–81. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Mirandé A. Hombres y machos: masculinity and Latino culture. Westview. Boulder CO, 1997

- Arciniega GM, Anderson TC, Tovar-Blank ZG, Tracey TJG. Toward a fuller conception of machismo: development of a traditional Machismo and Caballerismo Scale. J Couns Psychol. 2008; 55: 19–33. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Gutmann M. Changing men and masculinities in Latin America. Duke University Press. Durham and London, 2003

- Ramirez Rodriguez JC. Young Mexican men divided: a possibility for transforming masculinity. Men and masculinities around the world: transforming men's practices. Ruspini E, Hearn J, Pease B, Pringle KPalgrave MacMillan. New York, 2011; 143–158.

- Viveros Goya M. Masculinities and social intervention in Colombia. Men and masculinities around the world: transforming men's practices. Ruspini E, Hearn J, Pease B, Pringle KPalgrave MacMillan. New York, 2011; 125–142.

- White V, Greene M, Murphy E. The Synergy Project. Men and reproductive health programs: influencing gender norms. Washington DC: US Agency for International Development. Office of HIV/AIDS; 2003. Available from: http://www.usaid.gov/our_work/global_health/pop/.../gendernorms.doc [cited 1 June 2011].

- Barker G, Nascimento M, Segundo M, Pulerwitz J. How do we know if men have changed? Promoting and measuring attitude change with young men. Lessons from Program H in Latin America. Brasilia: United Nations, Division for the Advancement of Women (DAW) in collaboration with International Labour Organization (ILO), Joint United Nations Programmes on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2004. Available from: http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/egm/men-boys2003/OP2-Barker.pdf2003 [cited 1 June 2011].

- Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Verma R, Weiss E. Addressing gender dynamics and engaging men in HIV programs: lessons learned from horizons research. Public Health Rep. 2010; 125: 282–92.

- World Health Organization. WHO gender mainstreaming strategy. Integrating gender analysis and actions into the work of WHO. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/gender/mainstreaming/strategy/en/ [cited 1 June 2011].

- Women's Commission for Refugee Women and Children. Masculinities: male roles and male involvement in the promotion of gender equality. A resource packet. New York: Women's Commission for Refugee Women and Children. 2005. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/emerg/files/male_roles.pdf2005 [cited 1 June 011].

- Flood M. Harmful traditional and cultural practices related to violence against women and successful strategies to eliminate such practices – working with men. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) Expert Group Meeting – strategies for implementing the recommendations from the Secretary-General's Study on Violence against Women with Particular Emphasis on the Role of National Machineries. ; 2005. Available from: http://www.unescap.org/esid/gad/events/egm-vaw2007/discussion%20papers%20and%20presentations/michael%20flood's%20paper.pdf2007 [cited 1 June 2011].

- Evans J, Frank B, Oliffe JL, Gregory D. Health, illness, men and masculinities (HIMM): a theoretical framework for understanding men and their health. J Mens health. 2011; 8: 7–15. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Courtenay W. Behavioral factors associated with disease, injury, and death among men: evidence and implications for prevention. J Mens Stud. 2000; 9: 81–142. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Marston C, King E. Factors that shape young people's sexual behaviour: a systematic review. Lancet. 2006; 368: 1581–6. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Kostrzewa K. The sexual and reproductive health of young people in Latin America: evidence from WHO case studies. Salud Publica Mex. 2008; 50: 10–6.

- World Health Organization. What about the boys? A literature review on the health and development of adolescent boys. Geneva. World Health Organization. 2000. Available from: URL:http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2000/WHO_FCH_CAH_00.7.pdf [cited 1 June 2011].

- Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000; 50: 1385–401. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Courtenay WH. Engendering health: a social constructionist examination of men's health beliefs and behaviors. Psychol Men Masc. 2000; 1: 4–15. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: causes and prevention. Lancet. 2002; 35: 1423–9. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Watts C, Zimmerman C. Violence against women: global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 2002; 359: 1232–7. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006; 368: 1260–9. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Campbell JC. Health consequences of intimate partner violence. Lancet. 2002; 359: 1331–6. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Ellsberg M, Jansen HAFM, Heise L, Watts CH, Garcia-Moreno C. Intimate partner violence and women's physical and mental health in the WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence: an observational study. Lancet. 2008; 371: 1165–72. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Salazar M, Valladares E, Ohman A, Hogberg U. Ending intimate partner violence after pregnancy: findings from a community-based longitudinal study in Nicaragua. BMC Public Health. 2009; 9: 350.10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Sternberg P, White A, Hubley JH. Damned if they do, damned if they don't: tensions in Nicaraguan masculinities as barriers to sexual and reproductive health promotion. Men Masc. 2008; 10: 538–56. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Welsh P. Community development: a gendered activism? The masculinities question. Community Dev J. 2010; 45: 297–306. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Sternberg P. Challenging machismo: promoting sexual and reproductive health with Nicaraguan men. Gend Dev. 2000; 8: 89–99. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Barker G, Ricardo C, Nascimento M. Engaging men and boys in changing gender-based inequity in health: evidence from programme interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization and Instituto Promundo. 2007. Available from: http://www.who.int/gender/documents/Engaging_men_boys.pdf2007 [cited 1 June 2011].

- INIDE. VIII population survey and IV household survey. Educational characteristics of the population. Managua, Nicaragua. ; 2006. Available from: http://www.inide.gob.ni/censos2005/VolPoblacion/Volumen%20Poblacion%201-4/Vol.II%20Poblacion-Caracteristicas%20Educ.pdf [cited 1 June 2011].

- Welsh P, Stankovitch M, Bradbury A. Men aren't from Mars. Unlearning machismo in Nicaragua. Catholic Institute for International Relations. Managua Nicaragua, 2001

- Lancaster R. Life is hard. Machismo, danger and the intimacy of power in Nicaragua. University of California Press. California, 1992

- Berglund S. Competing everyday discourses: the construction of heterosexual risk-taking behaviour among adolescents in Nicaragua: towards a strategy for sexual and reproductive health empowerment. Hälsa och samhälle, Malmö högskola. 2008

- Kalk A, Kroeger A, Meyer R, Cuan M, Dickson R. Influences on condom use among young men in Managua, Nicaragua. Cult Health Sex. 2001; 3: 469–81. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Manji A, Peña R, Dubrow R. Sex, condoms, gender roles, and HIV transmission knowledge among adolescents in León, Nicaragua: implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Care. 2007; 19: 989–95. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Claeys P, Gonzalez C, Gonzalez M, Van Renterghem L, Temmerman M. Prevalence and risk factors of sexually transmitted infections and cervical neoplasia in women's health clinics in Nicaragua. Sex Transm Infect. 2002; 78: 204–7. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- INIDE. (2008). Nicaraguan Demographic and Health Survey 2006/2007. Final Report Managua. Nicaragua: National Institute for Information and Development.

- Solórzano I, Bank A, Peña R, Espinoza H, Ellsberg M, Pulerwitz J. Catalyzing individual and social change around gender, sexuality, and HIV: impact evaluation of Puntos de Encuentro's communication strategy in Nicaragua. Horizons Final Report. Washington DC: Population Council. 2008. Available from: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/horizons/Nicaragua_StigmaReduction.pdf [cited 1 June 2011].

- Kvale S. Interviews: an introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Sage Publications. Thousand Oaks CA, 1996

- García-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. WHO multi-country study on women's health and domestic violence against women: initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women's responses. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2005. Available from: http://www.who.int/gender/violence/who_multicountry_study/en/ [cited 5 June 2011].

- Soydan H. Using the vignette method in cross-cultural comparisons. Cross-national research methods in the social sciences. Hantrais L, Mangen SBiddles. London, 1996; 120–128.

- Glaser B, Strauss A. The discovery of grounded theory. Aldine. Chicago, 1967

- Berger PL, Luckmann T. The social construction of reality: a treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Penguin. London, 1967

- Glaser B. Theoretical sensitivity. The Sociology Press. Mill Valley CA, 1978

- UMDAC., Epidemiology Department of Public Health and Clinical Medicine Umeå University. OpenCode 3.4. Umeå: Umeå University. 2001.

- Dahlgren L, Emmelin M, Winkvist A. Qualitative methodology for international public health. Umeå University. UmeåSweden, 2004

- Weber M. Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft. Die Wirtschaft und die gesellschaftlichen Ordnungen und Mächte5th ed. Sieback PJCB Mohr. Tübingen, 1972; 1–30.

- Conell RW. The men and the boys. Polity Press. Cambridge, 2000

- Verma RK, Pulerwitz J, Mahendra V, Khandekar S, Barker G, Fulpagare P, et al.. Challenging and changing gender attitudes among young men in Mumbai, India. Reprod Health Matters. 2006; 14: 135–43. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Casey E, Smith T. ‘How Can I Not?’: men's pathways to involvement in anti-violence against women work. Violence Against Women. 2010; 16: 953–73. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Pulerwitz J, Barker G. Measuring attitudes toward gender norms among young men in Brazil. Men Masc. 2008; 10: 322–38. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Hughes JA, Martin PJ, Sharrock WW. Understanding classical sociology. Marx, Weber, Durkheim. SAGE Publications. London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi, 1995

- Latané B, Darley J. Bystander ‘apathy’. Am Sci. 1969; 57: 244–68.

- Casey EA, Ohler K. Being a positive bystander: male antiviolence allies’ experiences of ‘stepping up. ’. J Interpers Violence. 2011. [Published online before print]. Available from: http://jiv.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/08/02/0886260511416479.abstract [cited 5 June 2011].

- Broido EM. The development of social justice allies during college: a phenomenological investigation. J Coll Stud Dev. 2000; 41: 3–18.

- Alsop R, Heinsohn N. Measuring empowerment in practice: structuring analysis and framing indicators. Washington DC: World Bank. 2005. Available from: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTEMPOWERMENT/Resources/41307_wps3510.pdf [cited 5 June 2011].

- Mosedale S. Assessing women's empowerment: towards a conceptual framework. J Int Dev. 2005; 17: 243–57. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Gupta G, Whelan D, Allendor A. Integrating gender into HIV/AIDS programmes. A review paper. Geneva: Department of Gender and Women's Health Family and Community Health. World Health Organization. 2003. Available from: http://www.who.int/gender/hiv_aids/en/Integrating[258KB].pdf [cited 5 June 2011].

- Marshall MN. Sampling for qualitative research. Fam Pract. 1996; 13: 522–6. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.

- Lincoln Y, Guba E. Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications. Newbury Park CA, 1985

- McAdam D. The biographical consequences of activism. Am Sociol Rev. 1989; 54: 744–60. 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17262.