Abstract

Background

Managing cancer in a multicultural environment poses several challenges, which include the communication between the patient and the healthcare provider. Culture is an important consideration in clinical care as it contributes to shaping patients’ health-related values, beliefs, and behaviours. This integrative literature review gathered evidence on how culturally competent patient–provider communication should be delivered to patients diagnosed with cancer.

Design

Whittemore and Knafl's approach to conducting an integrative literature review was used. A number of databases were systematically searched and a manual search was also conducted. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were set and documents were critically appraised independently by two reviewers. Thirty-five documents were included following these processes. Data extraction and synthesis followed and were also independently verified.

Results

Various strategies and personal characteristics and attitudes for culturally competent communication were identified. The importance of culturally competent healthcare systems and models for culturally competent communication were also emphasised. The findings related to all themes should be treated with caution as the results are based mostly on low-level evidence (Level VII).

Conclusions

More rigorous research yielding higher levels of evidence is needed in the field of culturally competent patient–provider communication in the management of cancer. Most of the available literature was classified as non-research evidence. The themes that emerged do, however, provide some insight into how culturally competent patient–provider communication may be delivered in order to improve treatment outcomes in patients diagnosed with cancer.

To access the supplementary material for this article, please see Supplementary files under ‘Article Tools’.

Introduction

Communicating with cancer patients can be challenging for healthcare providers. The life-threatening nature of the illness, the physical and psychological suffering of cancer patients (Citation1), and the responsibility of conveying complex health information to the patient while also managing their emotions (Citation2) are just some of the challenges impacting patient–provider communication in the cancer setting. Managing cancer in a multicultural context further complicates patient–provider communication (Citation3). Culture can be defined as ‘a system of beliefs, values, rules and customs that is shared by a group and is used to interpret experiences and direct patterns of behavior’ (Citation4). Culture plays a significant role in how patients’ health-related values, beliefs, and behaviours are shaped (Citation4) and affects how patients and communities approach the diagnosis and treatment of cancer as well as their trust towards healthcare providers and institutions (Citation5). Similarly, culture has been shown to affect professionals’ and institutions’ approach to minority patients (Citation5) and contributes substantially to the existing disparities in access to healthcare for minority and underprivileged patients (Citation1). An example is South Africa as this country presents with disparities in health and wealth that are amongst the highest in the world (Citation6). The majority of the South African population is classified as African (80.5%) (Citation7) and consists of a number of ethnic groups each with their own African language. South Africa has 11 official languages comprising various African languages, English, and Afrikaans. African patients understand health and illness within a framework of indigenous beliefs which takes the biological, social, emotional and spiritual aspects into account and where cancer may be conceptualised as resulting from witchcraft or conflicts in relationships. Consultation with traditional healers is thus often preferred to Western medicine (Citation8). Late presentation of cancer patients due to a preference for traditional approaches to healing has been reported in local and international studies (Citation8–Citation10). In addition, consultation with family members and the elders is a common practice before any major life decisions (Citation8), including treatment decisions like surgery, are made. South African patients presenting for treatment in the public health sector tend to be confronted with cultural and language discordant medical encounters as healthcare providers are often not of the same cultural background as the patient; may have more urban, Western perspectives of health and illness; and are trained in English or Afrikaans. Similar reflections regarding culturally discordant medical encounters are noted in international literature where countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom serve populations from diverse cultural backgrounds (Citation11–Citation13).

Cultural competence has been proposed as a strategy to improve access to healthcare and the quality of healthcare, and to reduce and/or eliminate health disparities (Citation14–Citation20). Cultural competence has varied definitions (Citation1, Citation17) (Citation21–Citation27) but seems to require the acquisition, integration, and application of awareness, knowledge, skills, and attitudes regarding cultural differences in order to effectively deliver expert care that meets the unique cultural needs of patients; to manage and reduce cross-cultural misunderstanding in discordant medical encounters; and to successfully negotiate mutual treatment goals with patients and families from different cultural backgrounds. Surbone (Citation1) suggested that culturally competent cancer care can improve treatment outcomes and viewed cultural competence as a requirement for healthcare professionals working in the cancer setting.

Reviewing the literature revealed that there were no systematic or integrative reviews available on culturally competent patient–provider communication with cancer patients. This integrative literature review is part of a broader study for developing an evidence-based practice guideline for culturally competent patient–provider communication with patients diagnosed with osteosarcoma in a specific South African context. Healthcare providers in cross-cultural clinical settings have to be able to communicate an understanding of patients’ cultural beliefs while at the same time communicating the urgency of intervening and the effect on survival if patients choose to delay intervention while engaging in cultural practices. This integrative literature review aims to provide some insight into how to deliver culturally competent patient–provider communication to adult patients diagnosed with cancer.

Methods

An integrative literature review was performed in accordance with the guidelines provided by Whittemore and Knafl (Citation28). These authors propose the following key stages: problem identification, literature search, data evaluation, data analysis, and data presentation. This literature review methodology was selected as it allows for the inclusion of studies with diverse methodologies, and for the combination of data from theoretical and empirical literature, to facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of a particular issue or healthcare problem (Citation28). The review question was formulated using the PICO guide (Citation29). The aim of the integrative review was to determine how culturally competent patient–provider communication is best delivered to adult patients diagnosed with cancer.

Literature search

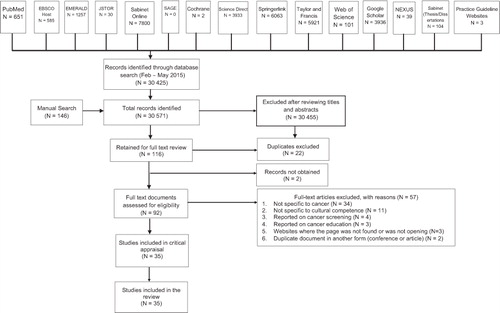

An experienced librarian assisted the primary author with selecting the keywords and databases, and with conducting the search. In the period February to May 2015, various electronic databases as is depicted in , were searched. Evidence-based practice guideline websites were also searched, including the National Guideline Clearinghouse, National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), New Zealand Guidelines Group (NZGG), Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO), The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN), eGuidelines, Guidelines International Network, Turning Research into Practice (Trip) Database, Canadian Medical Association (CMA) Infobase, and Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Evidence-based Practice Database. A manual search was conducted using Google Scholar and the following websites: (www.culturediversity.org/cultcomp.htm, www.diversityrx.org/HTML/DIVRX.htm, www.omhrc.gov/templates/, www.sis.nlm.nih.gov/outreach/multicultural.html, www.npin.cdc.gov/pages/cultural-competence, www.adventisthealthcare.com/health/equity-and-wellness/, www.hrsa.gov/culturalcompetence/qualityhealthservices, www.cancer.gov/aboutnci/organization/crchd,iccnetwork.org/pocketguide/, www.cdc.gov/cancer/healthdisparities/statistics/ethnic.htm).

The following keywords were used in various combinations to conduct the literature searches: patient–provider communication; doctor–patient communication; physician–patient communication; cancer; oncology; cultural competence; culturally competent communication; cross-cultural communication; multicultural communication; and transcultural communication. Various sets of keywords were used that were deemed suitable for the databases, to ensure that no relevant literature was missed.

Inclusion and exclusion of records

The following inclusion criteria were used: relevant literature from 1982 was included, as the term ‘cultural competence’ first appeared in the literature in 1982 (Citation30). The literature on cultural competence had to pertain specifically to cancer or to cultural aspects of communication in the context of cancer care, and had to be available in English. Owing to the paucity of research documents available on the topic, non-research documents were also included when these were appraised as relevant to the review question (Citation31).

Regarding exclusion of records, literature that pertained to cultural competence in disciplines other than the context of cancer care was excluded from the review. Literature pertaining to paediatric oncology, cancer patient education not related to the interaction between patients and healthcare providers, and cancer screening were also excluded. Inclusion and exclusion of records was independently verified by the second author using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. represents the search process for this integrative literature review.

Data evaluation

A comprehensive and frequently used hierarchy system () was chosen to rate the evidence (Citation32).

Table 1 Rating system for the hierarchy of evidence for intervention/treatment questions (Citation32)

Critical appraisal tools were used to carefully and systematically examine the records in order to judge its trustworthiness, and its value and relevance in a particular context (Citation33). The primary author and other authors independently appraised the documents.

Two quantitative studies were appraised using the Health Care Practice Research and Development Unit (HCPRDU) Evaluation Tool for Quantitative Studies (Citation34). Four qualitative studies were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for assessing qualitative research (Citation35). Non-research records (N=29) were appraised using the Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-based Practice tool for Non-Research Evidence Appraisal (Citation31). After critical appraisal was done, all 35 records were included for data extraction and synthesis.

Data analysis

Data relevant to the review question were extracted from the included records. The primary author conducted the data extraction and content analysed the extracted data. The second author independently verified both processes in order to improve the rigour of the data analysis. Data display matrices were developed to facilitate data comparison and synthesis. The researchers employed an iterative process by repeating the data extraction and synthesis numerous times, in order to ensure the verification of the results.

Results

The 35 records that met the inclusion criteria are presented in the Supplementary file. Two of the records could be classified as level IV evidence, 8 as level VI evidence, and 25 as level VII evidence. Six themes emerged from the data extraction and synthesis. Skills that healthcare providers require for culturally competent communication was the most prominent and most densely represented theme in the literature (N=32), followed by healthcare provider awareness (N=24), healthcare provider knowledge (N=22), culturally competent healthcare systems (N=22), personal characteristics and attitudes (N=13), and models for cross-cultural communication (N=3). Themes are discussed and summarised in in the order of frequency with which they appeared in the literature. The literature referred to a range of healthcare professionals, including oncologists, surgeons, and nurses, but most of the sources did not specify the type of healthcare professional involved; hence, the term healthcare provider is used generically.

Table 2 Themes and subthemes

Healthcare provider skills (N=32)

This theme encompasses the skills required for culturally competent communication. It addresses actions required for integrating cultural knowledge (Citation5, Citation36) and knowledge of diverse population health into clinical practice (Citation24). Effective communication skills (Citation11, Citation18) (Citation37) were most prominently featured in the included literature (N=18). Using simple language (Citation18–Citation42) and checking patient understanding of information given (Citation36, Citation39–Citation41, Citation43) (Citation44) were the most cited communication skills.

Managing difference in the patient–provider encounter (N=13) can be challenging. The literature underscored that healthcare providers should avoid stereotyping and generalisations (Citation5, Citation11) (Citation37, Citation18) (Citation36, Citation44) (Citation45).

Skills related to building the patient–provider relationship (N=12) ranged from the significance of the initial medical encounter (Citation11, Citation36) (Citation46, Citation47) to specific relational skills like building rapport (Citation41, Citation48), gaining patient trust (Citation11, Citation17) (Citation49), addressing patients appropriately according to their cultural preference (Citation11), and engaging in culturally sensitive communication (Citation50).

The importance of assessment skills were also underscored in the literature (Citation18, Citation36) and specific assessment skills for conducting a patient assessment beyond the biomedical aspect (N=13) were highlighted (Citation41, Citation46) (Citation51).

Key findings pertaining to accommodating the patient's family (N=5) included communicating with the patient's extended family (Citation11), investing in and gaining family trust (Citation11, Citation38), balancing autonomy and dependency when meeting patient and family needs (Citation52), and affording the family the maximum control possible (Citation51). Accommodating religion and spirituality (N=4) by recognising patients’ spiritual needs (Citation51), acknowledging religion in the patient's belief system (Citation11, Citation42), and demonstrating respect for religious beliefs (Citation38) were also identified as key findings.

Healthcare provider awareness (N=24)

Cultural awareness is an essential part of delivering culturally competent patient–provider communication (Citation46, Citation53). Contextual awareness (N=11) relates to variables such as the country's socio-political history (Citation41), socio-cultural factors (Citation45), patients’ phases of acculturation to the dominant culture (Citation47), and patient demographics in the service area (Citation38, Citation42) (Citation48, Citation52) (Citation54).

Self-awareness (N=9) (Citation11, Citation12) (Citation18, Citation36) with regard to the provider's own culture (Citation55); cultural beliefs (Citation19); health belief systems (Citation54); spirituality (Citation51); and cultural assumptions, personal biases, and stereotypes (Citation5, Citation19) (Citation45, Citation54) (Citation55) is supported by various authors.

Interpersonal awareness (N=5) with regard to inherent power differentials between healthcare providers and patients (Citation41), the interaction between patients and healthcare providers’ cultures during the medical encounter (Citation40, Citation55), and communication differences between cultures (Citation36, Citation48) was highlighted in the literature.

Awareness of cultural expectations in the healthcare setting (N=5) pertains to the level of family involvement required (Citation1, Citation44) (Citation52, Citation54) (Citation56) and the degree of direction expected from healthcare providers which may be more than what typically predominates in Western settings (Citation54).

Healthcare provider knowledge (N=22)

This theme (N=22) highlights the acquisition of sound factual knowledge and an understanding of various cultural aspects (Citation11). When obtaining this culture-specific knowledge, healthcare providers should be cognizant of intra-cultural differences (Citation5, Citation36) (Citation44, Citation52) (Citation57).

Context-specific knowledge (N=9) relates to knowledge of cultural groups seeking services in the provider's clinical setting (Citation11, Citation18) (Citation36, Citation47) (Citation52, Citation58).

The importance of healthcare providers’ self-knowledge (N=6) pertaining to their own culture (Citation11, Citation18) (Citation36, Citation59), belief system (Citation18), and biases and stereotypes (Citation5, Citation11) (Citation18, Citation54) is emphasised.

Similarly, knowledge of patients’ cultures (N=5), including their health belief systems (Citation11, Citation39) (Citation44), their traditional health systems (Citation44), their processes of decision-making (Citation1, Citation44) (Citation47), and their standards of etiquette (Citation1, Citation44), is underscored in the literature.

Knowledge of the broader contextual variables (N=5) centres on the socio-political barriers to accessing healthcare (Citation11), the socio-historical cultural context and its influence on patients’ and families’ view of cancer (Citation5), and the socio-cultural differences between the self and patient and its impact on patient–provider communication (Citation18).

Culturally competent healthcare systems (N=22)

Culturally competent communication extends beyond the individual provider to the healthcare system. Culturally competent healthcare systems are agents for the provision of appropriate patient care for diverse population groups that extend beyond addressing individual patient needs, to policy and community level (Citation5, Citation37) (Citation39, Citation43). Specific organisational strategies for culturally competent communication are well-represented in the literature. The most common strategies were the use of patient navigators (Citation11, Citation24) (Citation47, Citation48) (Citation60, Citation61) and professional translators (Citation1, Citation5) (Citation11, Citation39) (Citation41, Citation44) (Citation45, Citation48) (Citation54, Citation56) (Citation57, Citation59).

Healthcare providers’ personal characteristics and attitudes (N=13)

This theme highlights healthcare providers taking responsibility for cultural aspects of health and illness, and for combating discrimination in healthcare settings (Citation45). The literature provided an extensive list of healthcare provider personal characteristics and attitudes that can facilitate culturally competent communication which is featured in . The most prominently featured healthcare provider attitude pertained to demonstrating respect for cultural diversity and patients’ cultural values (Citation5, Citation11) (Citation39, Citation42) (Citation45, Citation52) (Citation54, Citation62).

Models of effective cross-cultural communication (N=3)

Models of effective cross-cultural communication (N=3) have been cited in some of the documents included in this integrative review. Kleinman's questions (Citation17, Citation57), the LEARN Model (Citation36, Citation57), the BELIEF Model (Citation57), and the Four Habits Model of Highly Effective Clinicians emerged as key findings with regard to this theme.

Discussion

The aim of the integrative review was to determine how culturally competent patient–provider communication is best delivered to adult patients diagnosed with cancer. Several important themes emerged about how this can be achieved. Despite the exhaustive nature of the integrative review a number of limitations remain. Only databases available at the university where the searches were conducted were used. Interlibrary loans were then used to obtain other documents. Two key documents could not be used because they could not be obtained by the university libraries. Most of the documents have been evaluated as level VII evidence (N=25), the lowest level of evidence. Eight of the documents fulfil the criteria for level VI evidence, and only two of the documents could be evaluated as level IV evidence.

There are a number of possible reasons for the lack of research at higher levels of evidence. The concept of cultural competence first appeared in the social work and counselling psychology literature in 1982 (Citation30). A report issued by the US Department of Health and Human Services in 2001 highlighted that despite widespread policy recognition of the important role that cultural competence plays in facilitating accessible and effective healthcare for culturally diverse populations, policymakers were still in the early stages of defining cultural competence in a manner that facilitates empiricism and implementation (Citation63). This lack of consensus on defining this concept was apparent in this report almost two decades after the concept first appeared in the literature. More recent literature still reports that despite the proliferation of cultural competency frameworks and models since their inception, there is still no one authoritative framework available (Citation64, Citation65). There are a number of consonant concepts available such as culturally appropriate care, culturally sensitive care, and so forth, which further complicate the cultural competence theoretical and applied landscape (Citation30, Citation64). A lack of uniformity in policy making with regard to comprehensive versus specific approaches to cultural competence has resulted in a burgeoning of ideas and methodologies about what constitutes cultural competence (Citation63). The literature also indicates a lack of agreement on how best to implement cultural competence (Citation65), and research on interventions for improving cultural competence in healthcare tends to lack methodological rigour (Citation64). Hence, despite the recognition of how beneficial cultural competence can be in rendering effective healthcare services to diverse population groups, the lack of uniformity on conceptual, intervention, and policy fronts results in a myriad of disparate information. It is therefore hypothesised that while there is extensive literature on cancer health disparities and use of ‘cultural competence’ as a means of addressing these disparities (Citation25, Citation66–Citation68), research on how best to deliver culturally competent patient–provider communication to patients diagnosed with cancer is sparse owing to the aforementioned challenges associated with the concept of cultural competence.

Despite these challenges, the results of this integrative literature review provided useful insights for clinical practice. Engaging in culturally competent communication requires ‘communicating with awareness and knowledge of healthcare disparities and understanding that socio-cultural factors have important effects on health beliefs and behaviours, as well as having skills to manage these factors appropriately’ (Citation20). The first three themes clearly illustrate this definition. The personal characteristics and attitudes required for culturally competent communication also emerged from the literature. Furthermore, the findings extend from the individual provider to emphasising culturally competent healthcare systems and models for culturally competent communication that can guide practice. The literature highlights the importance of this extension by emphasising that cultural competence should be addressed at policy, organisational, and systems levels (Citation41). The information was categorised into various themes and subthemes to facilitate ease of reference and application in clinical practice. However, the findings related to these themes should be treated with caution as the results are based mostly on low-level evidence (Level VII) (Citation32), indicating the lack of research using methodologies linked to high levels of evidence in this study area. In addition, all the studies were international and only one of the studies focused on an African refugee population albeit in the context of the US. The unique African setting necessitates and could greatly benefit from research on culturally competent patient–provider communication at higher levels of evidence.

Conclusions

The findings of the integrative literature review have important practice implications. The themes that emerged during the integrative review process provide some insight into the ‘how’ of delivering culturally competent patient–provider communication to adult patients diagnosed with cancer. The grave need for scientifically rigorous research yielding higher levels of evidence in the field of cancer and culturally competent patient–provider communication is emphasised by the lack of quality evidence for all the themes that were presented in this integrative literature review.

Authors’ contributions

Ms Brown has made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work; final approval of the version to be submitted to the journal; and has agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Dr ten Ham-Baloyi has made substantial contributions to the design of the work; the analysis and interpretation of data for the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and has agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Prof van Rooyen has made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and has agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Prof Aldous has made a substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work; revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and has agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Dr Marais has made a substantial contribution to the conception and design of the work; revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; and has agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the PhD study was obtained from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC) of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) where the PhD study is registered. However, this is an integrative literature review and there were no human subjects involved in this article.

Conflicts of interest and funding

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Paper context

Patient–provider communication in cancer care as well as cross-cultural clinical settings is known to be challenging. This article provides information on how healthcare providers can deliver culturally competent care to cancer patients when working in cross-cultural clinical settings. The integrative literature review was performed to explore existing evidence and revealed that more rigorous research yielding higher levels of evidence is needed in the field of culturally competent patient–provider communication with cancer patients.

Supplementary file

Download PDF (276.1 KB)Notes

To access the supplementary material for this article, please see Supplementary files under ‘Article Tools’.

References

- Surbone A. Cultural aspects of communication in cancer care. Support Care Cancer. 2008; 16: 235–40.

- Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet. 2004; 363: 312–19.

- Butow PN, Tattersall MHN, Goldstein D. Communication with cancer patients in culturally diverse societies. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997; 809: 317–29.

- Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE. (2016). Cross-cultural care and communication. Available from: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/cross-cultural-care-andcommunication?source=machineLearning&search=patient-provider+communication&selectedTitle=2%7E150§ionRank=1&anchor=H3#H3.

- Kagawa-Singer M, Valdez Dadia A, Surbone A. Cancer, culture, and health disparities time to chart a new course?. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010; 60: 12–39.

- Benatar SR. The challenges of health disparities in South Africa. SAMJ. 2013; 103: 154–155.

- Statistics South Africa. Midyear population estimates 2015. Available from: http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0302/P03022015.pdf [cited 17 August 2016]..

- Vorobiof DA, Sitas F, Vorobiof G. Breast cancer incidence in South Africa. J Clin Oncol. 2001; 19: 125s–7s.

- Mdondolo N, De Villiers L, Ehlers V. Cultural factors associated with the management of breast lumps amongst Xhosa women. Health SA Gesondheid. 2003; 8: 86–97.

- Merriam S, Muhamad M. Roles traditional healers play in cancer treatment in Malaysia: implications for health promotion and education. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013; 14: 3593–601.

- Pierce RL. African-American cancer patients and culturally competent practice. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1997; 15: 1–17.

- Atkin K, Chattoo S, Crawshaw M. Clinical encounters and culturally competent practice: the challenges of providing cancer and infertility care. Policy Polit. 2014; 42: 581–96.

- Gao G, Burke N, Somkin CP, Pasick R. Considering culture in physician–patient communication during colorectal cancer screening. Qual Health Res. 2009; 19: 778–89.

- Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Ananeh-Firempong O II. Defining cultural competence: a practical framework for addressing racial/ethnical disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003; 188: 293–302.

- Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, Park ER. Cultural competence and health care disparities: key perspectives and trends. Health Aff. 2005; 24: 499–505.

- Brach C, Fraser I. Reducing disparities through culturally competent health care: an analysis of the business case. QMHC. 2002; 10: 15–28.

- Kagawa-Singer M.Surbone A, Zwitter M, Rajer M, Stiefel R. Teaching culturally competent communication with diverse patients and families. New challenges in communication with cancer patients. 2013; New York: Springer. 365–75.

- Matthews-Juarez P, Juarez PD. Cultural competency, human genomics, and the elimination of health disparities. Soc Work Public Health. 2011; 26: 349–65.

- Surbone A, Baider L. Personal values and cultural diversity. J Med Pers. 2013; 11: 11–18.

- Taylor SL, Lurie N. The role of culturally competent communication in reducing ethnic and racial healthcare disparities. Am J Manag Care. 2004; 10: SP1–SP4.

- Betancourt JR. Cross-cultural medical education: conceptual approaches and frameworks for evaluation. Acad Med. 2003; 78: 560–69.

- Betancourt JR. Cultural competency: providing quality care to diverse populations. Consult Pharm. 2006; 21: 988–95.

- Cooper LA, Roter DL.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Patient-provider communication: the effect of race and ethnicity on process and outcomes of healthcare. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. 2003; Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 552–93.

- Coughlin SS, Matthews-Juarez P, Juarez PD, Melton CE, King M. Opportunities to address lung cancer disparities among African Americans. Cancer Med. 2014; 3: 1467–76.

- Kagawa-Singer M, Kassim-Lakha S. A strategy to reduce cross-cultural miscommunication and increase the likelihood of improving health outcomes. Acad Med. 2003; 78: 577–87.

- Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mackenzie ER. Cultural competence: essential measurements of quality for managed care organizations. Ann Intern Med. 1996; 124: 919–21.

- Kemp C. Cultural issues in palliative care. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2005; 21: 44–52.

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. J Adv Nurs. 2005; 52: 546–53.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Developing NICE guidelines: the manual. 2014. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/ [cited 18 February 2016]..

- Gallegos JS, Tindall C, Gallegos SA. The need for advancement in the conceptualisation of cultural competence. Adv Soc Work. 2008; 9: 51–62.

- Newhouse RP, Dearholt SL, Poe SS, Pugh LC, White KM. John Hopkins nursing evidence-based practice: model and guidelines. 2007; Indianapolis, IN: Sigma Theta Tau International.

- Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E. Evidence-based practice in nursing and healthcare: a guide to best practice. 2nd ed. 2011; Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health ∣ Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Burls A. What is critical appraisal? What is …? Series. 2nd ed. 2009. Available from: http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/painres/download/whatis/What_is_critical_appraisal.pdf [cited 10 August 2014]..

- Long AF, Godfrey M, Randall T, Brettle AJ, Grant MJ. Developing evidence based social care policy and practice. Part 3: feasibility of undertaking systematic reviews in social care. 2002; Leeds: Nuffield Institute for Health.

- National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. Critical appraisal tools to make sense of evidence. 2011; Hamilton, ON: McMaster University.

- Pesquera M, Yoder L, Lynk M. Improving cross-cultural awareness and skills to reduce health disparities in cancer. Medsurg Nurs. 2008; 17: 114–20.

- Lavizzo-Mourey RJ, Mackenzie E. Cultural competence-an essential hybrid for delivering high quality care in the 1990's and beyond. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1995; 107: 226–37.

- Chaturvedi SK, Strohschein FJ, Saraf G, Loiselle CG. Communication in cancer care: psycho-social, interactional and cultural issues. A general overview and the example of India. Front Psychol. 2014; 5: 1332.

- Ngo-Metzger Q, Telfair J, Sorkin DH, Weidmer B, Weech-Maldonado R, Hurtado M, etal. Cultural competency and quality of care: obtaining the patient's perspective. 2006; The Commonwealth Fund.

- Rollins LK, Hauck FR. Delivering bad news in the context of culture: a patient-centered approach. JCOM. 2015; 22: 21–26.

- Shahid S, Durey A, Bessarab D, Aoun SM, Thompson SC. Identifying barriers and improving communication between cancer service providers and Aboriginal patients and their families: the perspective of service providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013; 13: 460.

- Song L, Weaver MA, Chen RC, Bensen JT, Fontham E, Mohler JL, etal. Associations between patient–provider communication and socio-cultural factors in prostate cancer patients: a cross-sectional evaluation of racial differences. Patient Educ Couns. 2014; 97: 339–46.

- Kreps GL. Communication and racial inequities in health care. Am Behav Sci. 2006; 49: 760–74.

- Mullin VC, Cooper SE, Eremenco S. Communication in a South African cancer setting: cross-cultural implications. Int J Rehabil Health. 1998; 4: 69–82.

- Pârvu A, Dumitraş S, Gramma R, Enache A, Roman G, Moisa S, etal. Disease in RROMA communities – an argument for promoting medical team cultural competence. Stud UBB Philos. 2013; 58: 23–35.

- Cohen MZ, Palos G. Culturally competent care. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2001; 17: 153–8.

- Lichtveld MY, Smith A, Weinberg A, Weiner R, Arosemena FA.Georgakilos A. Creating a sustainable cancer workforce: focus on disparities and cultural competence. Cancer prevention – from mechanisms to translational benefits. 2012; Rijeka, Croatia: InTech. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/2253.

- Thomas BC, Lounsberry LL, Carlson LE.Kissane DW, Bultz BD, Butow PN, Finlay IG. Challenges in communicating with ethnically diverse populations. Handbook of communication in oncology and palliative care. 2010; New York: Oxford University Press. 375–87.

- Surbone A, Baider L, Kagawa-Singer M. Cultural competence in the practice of patient–family-centered geriatric oncology. J Geriatr Oncol. 2010; 1: 45–7.

- Mitchell J. Cross-cultural issues in the disclosure of cancer. Cancer Pract. 1998; 6: 153–60.

- Longo L, Slater S. Challenges in providing culturally-competent care to patients with metastatic brain tumours and their families. Can J Neurosci Nurs. 2014; 36: 8–14.

- Die Trill M, Holland J. Cross-cultural difference in the care of patients with cancer: a review. Gen Hosp Psychiat. 1993; 15: 21–30.

- Huang Y, Yates P, Prior D. Factors influencing oncology nurses’ approaches to accommodating cultural needs in palliative care. J Clin Nurs. 2009; 18: 3421–9.

- Barclay JS, Blackhall LJ, Tulsky JA. Communication strategies and cultural issues in the delivery of bad news. J Palliat Med. 2007; 10: 958–77.

- Dein S. Culture and cancer care: anthropological insights. 2006; Berkshire, England: Open University Press.

- Beyene Y. Medical disclosure and refugees telling bad news to Ethiopian patients. In cross-cultural medicine-a decade later [Special Issue]. West J Med. 1997; 157: 328–32.

- Epner DE, Baile WF. Patient-centered care: the key to cultural competence. Ann Oncol. 2012; 23: iii33–iii42.

- Muñoz-Antonia T. Don't neglect cultural diversity in oncology care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2014; 12: 836–37.

- Chambers T.Angelos P. Cross-cultural issues in caring for patients with cancer. Ethical issues in cancer patient care. 2nd ed. 2005; Springer. 45–64.

- Moore AD, Hamilton JB, Knafl GJ, Godley PA, Carpenter WR, Bensen JT, etal. Patient satisfaction influenced by interpersonal treatment and communication for African American men: the North Carolina–Louisiana Prostate Cancer Project (PCaP). Am J Men's Health. 2012; 6: 409–19.

- Murphy MM, Tseng JF, Shah SA. Disparities in cancer care: an operative perspective. Surgery. 2010; 147: 733–37.

- Surbone A. Cultural competence: why?. Ann Oncol. 2004; 15: 697–9.

- Office of Minority Health. National standards for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care. 2001; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Final report.

- Truong M, Paradies Y, Priest N. Interventions to improve cultural competency in healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014; 14: 99.

- Vega WA. Higher stakes for cultural competence. Gen Hosp Psychiat. 2005; 27: 446–50.

- Geiger HJ.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Racial and ethnic disparities in diagnosis and treatment: a review of the evidence and a consideration of causes. Unequal treatment: –confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. 2003; Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 417–54.

- Johnston Lloyd LL, Ammary NJ, Epstein LG, Johnson R, Rhee K. A transdisciplinary approach to improve health literacy and reduce disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006; 7: 331–5.

- Johnson KRS. Ethnocultural influences in cancer. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 1998; 5: 357–64.