Abstract

Background

The Aboriginal nations of Canada have higher incidences of chronic diseases, coinciding with profound changes in their environment, lifestyle and diet. Traditional foods can protect against the risks of chronic disease. However, their consumption is in decline, and little is known about the complex mechanisms underlying this trend.

Objective

To identify the factors involved in traditional food consumption by Cree Aboriginal people living in 3 communities in northern Quebec, Canada.

Design

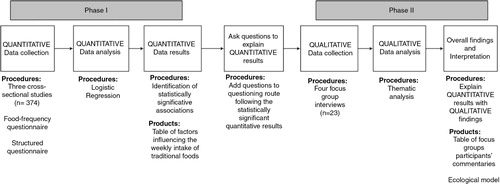

A mixed methods explanatory design, including focus group interviews to interpret the results of logistic regression.

Methods

This study includes a secondary data analysis of a cross-sectional survey of 3 Cree communities (n=374) and 4 focus group interviews (n=23). In the first, quantitative phase of the study, data were collected using a food-frequency questionnaire along with a structured questionnaire. Subsequently, the focus group interviews helped explain and build on the results of logistic regressions.

Results

People who consume traditional food 3 days or more weekly were more likely to be 40 years old and over, to walk 30 minutes or more per day, not to have completed their schooling, to live in Mistissini and to be a hunter (p<0.05 for all comparisons). The focus group participants provided explanations for the quantitative analysis results or completed them. For example, although no statistical association was found, focus group participants believed that employment acts as both a facilitator and a barrier to traditional food consumption, rendering the effect undetectable. In addition, focus group participants suggested that traditional food consumption is the result of multiple interconnected influences, including individual, family, community and environmental influences, rather than a single factor.

Conclusions

This study sheds light on a number of factors that are unique to traditional foods, factors that have been understudied to date. Efforts to promote and maintain traditional food consumption could improve the overall health and wellbeing of Cree communities.

Over the last few decades, the Aboriginal nations of Canada have had higher incidences of chronic diseases, coinciding with profound changes in their environment, lifestyle and diet (Citation1). The 9 Cree communities of Eastern James Bay have followed this trend, which is described in detail elsewhere (Citation2). The Cree diet, which was traditionally based on the consumption of wild animals and fish, now consists mainly of market foods. Several studies have reported that the consumption of traditional foods, such as wild animals, fish, birds and berries, is in decline (Citation3, Citation4). A diet rich in traditional foods can potentially protect against the risks of chronic disease due to its high levels of protein, quality fats, vitamins and minerals (Citation5, Citation6).

In 2005, Willows noted the lack of understanding of the determinants of food intake among Aboriginal nations (Citation7). The influences on food consumption are multifactorial (Citation7–Citation10), and the few studies that do exist have pointed out certain factors that are strongly associated with traditional food consumption (Citation7, Citation11) (Citation12). Therefore, an extensive literature review was undertaken to identify factors previously associated with traditional food consumption: living in a small and isolated community facilitates consumption (Citation6), as does being an older hunter, being physically active and practicing traditional activities (Citation12–Citation14).

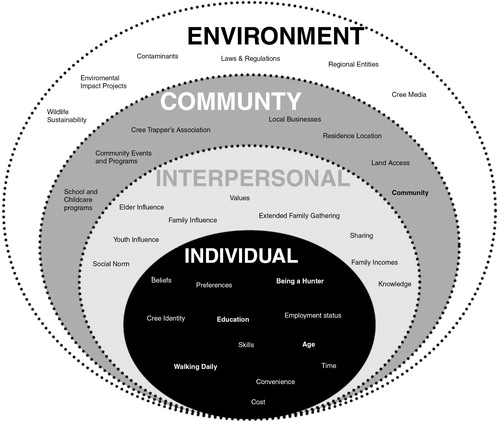

Many studies have explored food consumption models, from a wide variety of disciplines and perspectives (Citation8, Citation15–Citation18). The ecological model is particularly interesting because it suggests that traditional food consumption is influenced not only by individual variables but also by social and environmental factors and their interactions, thus involving different levels of influence (Citation19–Citation23). A 4-level ecological model, inspired from previous studies (Citation15, Citation16) (Citation21), has been proposed as a conceptual framework to map the multiple factors involved in traditional food consumption. This model considers environmental, cultural and social influences on aboriginal populations (Citation22). Moreover, our choice of an ecological approach is culturally appropriate, being in keeping with the Cree concept of health, miyupimaatisiiun, as defined by Adelson, which goes beyond the idea of individual health to encompass a healthy and respectful relationship between the community and the natural environment (Citation24).

The aim of this study was first to identify, using quantitative analysis, the factors associated with traditional food consumption, and second, to help explain these results based on the findings of focus group interviews.

Material and methods

To explore the factors associated with traditional food consumption by the Cree, we used what Creswell calls a “sequential explanatory mixed methods design” () (Citation25, Citation26) to help explain the quantitative analysis results. In the first phase, quantitative findings were obtained from a secondary analysis of 3 cross-sectional studies as part of the Multi-Community Environment and Health Longitudinal Study in Iyiyuu Aschii (n=374). The overall methodology of this study is described in detail elsewhere (Citation27, Citation28). In the second study phase, we used focus group interviews to help explain the quantitative results.

Quantitative data collection (phase I)

In Mistissini (pop. 3,000), data were collected over a period of 2 months during the summer of 2005. Data were collected in Eastmain (pop. 500) and Wemindji (pop. 500) over a 2-month period in 2007. These 2 communities are smaller and more remote than Mistissini, but all 3 communities are accessible by road.

Data were analysed on a total of 374 participants aged from 18 to 90 years. Participants were selected randomly using stratified population sampling.

To assess traditional food intake, a traditional food-frequency questionnaire covering a 1-year period was developed in partnership with community members, taking into account seasonal variations and availability (Citation29). The interviewers who administered the questionnaire were selected from the community members. They received training on interviewing techniques from the nutritionists’ research team. An additional questionnaire was administered to gather information about the individual participants and their levels of physical activity. The variables used for the quantitative analysis are presented in Table . The interviews lasted 3 hours and were conducted in the Eeyou language (Cree).

Table I. Variables used in the quantitative analysis

At the completion of each interview, 1 member of the research team reviewed all the questionnaires.

Quantitative data analysis (phase I)

All analyses were conducted with SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v. 16.0), and p-values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. Logistic regression was used to control for confounding variables (Citation30) and to examine the multivariate relationships between traditional food consumption (≤3 times per week) and the following predictive variables: community, sex, age, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, self-reported health status, worries about pollution, employment status, education, practice of hunting, daily walking, English spoken at home and number of people living in the household.

Table summarizes the definitions, sources, and categorization of all dependent and independent variables.

Qualitative data collection (phase II)

In 2009, 4 focus groups consisting of 4–8 people were organized in Mistissini, for a total of 23 individuals. Each group discussion lasted approximately 90 minutes. All focus groups were mixed-gender and were held at the participants’ preferred location and time. In order to increase participant similarity and to create a more comfortable environment for the discussions, homogenized sampling was used, whereby the participants were divided into 2 groups aged from 18 to 40 and 2 groups aged from 40 to 90 (Citation35). Participants were selected by nomination (Citation35). Previous participation in the Multi-Community Environment and Health Longitudinal Study was not required.

All discussions and interviews were held in English and/or Cree, and a Cree interpreter was used when necessary.

Following Krueger's recommendations, a questionnaire route was developed and pre-tested (Table ), using short, clear, simple and 1-dimensional open-ended questions (Citation35).

Table II. Questionnaire route

Focus group data analysis (phase II)

Each focus group discussion was recorded and then transcribed by an external contributor and then carefully reviewed by the moderator. Initially, major themes were organized manually and categorized into 4 levels of influence according to the ecological model: individual, interpersonal, community and environment. However, to ensure better data management, QDA Miner 3.2 software (Provalis Research, Montreal) was subsequently used to code and organize the transcribed data into factors. This allowed an iterative coding process that identified inconsistencies, and it facilitated updating and modifying the coding system (Citation35). The coding process assigned sentences and/or paragraphs to a factor. Then, in an iterative process, each factor was revisited and, if necessary, moved to another level or merged or divided into different factors. As a rigor criterion (Citation36) or respondent validation (Citation37), the results were presented to a group of community representatives.

This study was approved by the Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay, the research ethics committee of the University of Montreal, and the Band Councils. All participants provided their informed consent before participating in the study.

Results

Demographic characteristics (phase I)

Table presents the data collected from the 374 participants enrolled in the Multi-Community Environment and Health Longitudinal Study in Iyiyuu Aschii from 2005 to 2007. Significant differences within the 3 communities are seen in education, employment status, perception of health, worries about pollution and traditionnal food consumption.

Table III. Characteristics of 3 communities in the multi-community environment and health longitudinal study in Iyiyuu Aschii

Logistic regression (phase I)

Table summarizes the associations tested in the full logistic regression model. Positive associations were found between traditional food consumption and the variables age, daily walking, education, hunter and community (p<0.05 for all comparisons).

Table IV. Factors influencing traditional food weekly intake (<3 times– ≥3 times): a logistic regression (n=374)

People who reported consuming traditional foods 3 days or more per week were more likely to be from 40 to 90 years old, to walk 30 minutes or more per day, not to have completed any schooling, to be hunters and to live in Mistissini compared to those who consumed fewer traditional foods (p<0.05 for all comparisons). After adjusting for other variables, no associations were found with sex, BMI, smoking, employment status, health perception, worries about pollution, English spoken at home, or number of people in the household. According to the Hosmer-Lemeshow statistic, this model shows no evidence of lack of fit (Chi-square 3.246, df 8, p=0.918). Nagelkerke R2 is 0.43.

Further bivariate Chi-square analyses of the associations between independent variables showed collinearity between hunter and sex: 92% of males were hunters and 81.2% of females were non-hunters (p<0.001, data not shown). In addition, age acted as a confounding variable for a few variables. For example, 69.4% of people aged less than 40 attended high school, whereas only 41% of people over 40 had done so (p<0.001, data not shown). In addition, 64.7% of smokers were younger than 40 and 74.8% of non-smokers were over 40 (p<0.001, data not shown). As for employment status, 26.4% of people under 40 were unemployed and 73.6% were employed (p<0.001, data not shown). We also found significantly more frequent game consumption in Mistissini (p<0.001, Table ). Mistissini also showed more frequent consumption of birds, fish and grease compared to Eastmain (p<0.05, Table ).

Focus group interviews (phase II)

In general, when presented with our quantitative findings, the focus group participants agreed with them. For example, they agreed that age, being a hunter, daily walking and education level influenced traditional food intake. However, they were surprised to learn that residents of Mistissini consumed traditional foods more frequently than residents of Wemindji and Eastmain, because they believed that living in an isolated community and having limited access to market foods would be strong influences on traditional food consumption. Similarly, focus group participants disagreed with the non-association found between traditional food consumption and employment status. They felt that employment acts as both a facilitator and a barrier to traditional food consumption (Table presents the participants’ explanations for our quantitative findings).

Table V. Focus group participants’ comments on the quantitative findings

In addition, the participants provided supplementary information on the factors influencing traditional food consumption that were not included in the original quantitative questionnaire. Whereas the quantitative analyses focused mainly on individual-level factors, the focus group participants identified a number of social- and environment-level factors. The most frequently mentioned factors were the powerful influence of peers on food consumption as well as factors related to projects with an environmental impact, such as forestry, mining, hydro-electricity, wildlife sustainability, and government laws and regulations. The participants believed that the family has a strong influence over traditional food consumption because families go hunting together, it is through family members that traditional knowledge get passed on and because hunters share their game within family members. In addition, they believed that traditional food consumption was greatly influenced by government laws, such as the law regulating the use of hunting territories and laws governing the distribution of traditional food through public and private channels. Furthermore, any actions that could affect the ecological environment, such as hydroelectric projects, mining and forestry, as well as measures taken to preserve wildlife and plants, were considered of great impact on traditional food consumption.

presents an ecological model of all the factors associated with traditional food consumption that were identified by the focus group. Four levels of influence are included: environment, community, interpersonal and individual. Although this model contains the factors associated with traditional food consumption, the degree of influence for each factor could vary according to individual participants. The boundaries between the levels of influence are highly permeable, as the relationships and interactions among individuals, groups and their environments are complex.

Discussion

This study contributes to the scientific literature by identifying the influence of certain individual-level factors on traditional food consumption and by presenting Cree participants’ explanations for the impact of these and other factors on their food consumption. The explanations of the Cree participants are consistent with the ecological model, which suggests that the factors involved in food consumption are related not only to individuals, but also to their interpersonal relationships and their relationships to the community and the broader environment. In addition, the factors Knowledge and Income, which are usually classified as individual factors in most ecological models (Citation22), were classified as interpersonal factors. In fact, the participants talked about traditional knowledge in the sense of collective knowledge, including the fact that this knowledge was passed down within families. The same held true for Income because each time they mentioned the money they needed in order to go hunting, they invariably referred to the costs for the family and the family income that this would entail. If the factors were categorized as individual alone, much of the interpretative richness would be lost. Another example is that we found no statistical association between employment status and traditional food consumption, which contradicts Batal's study (Citation38), but concurs with Wein's study (Citation39). Considering the individual level alone, this non-association could be explained by the suggestions of the focus group participants that although employment-generated income can help cover hunting expenses, employment reduces the time available for hunting. Perhaps income and time cancel each other out such that there is no detectable association between employment and traditional food consumption in the logistic regression. However, considering the overall ecological model, another possible hypothesis emerges: when hunting is practiced within a family, the resources are shared among the family members. Thus, a salaried person pays the expenses of other family members while the non-employed members spend time working around the hunting camp to prepare it for other family members. Individual-level factors have limited power to explain traditional food consumption practices and influences, which are strongly shaped by family and households. A further example is the factor Hunter. Our results concur with many studies showing that the presence of a hunter, trapper, or fisherman in the family has a positive effect on the frequency and quantity of bush food that is consumed (Citation12, Citation14) (Citation39). Within an ecological model, being a hunter has greater meaning, as it indicates social status, cultural values, accessibility to a hunting territory, and possession of a certain set of skills, knowledge and resources. These relationships and characteristics might not be thoroughly captured or understood when considered at the individual level alone.

Mistissini, the largest and least remote of the 3 studied communities, showed the highest traditional food consumption. This finding contrasts with previous studies that found an association between community size or remoteness and traditional food consumption. For example, in 2006, Chan et al. noted that in larger communities, traditional foods were sometimes less available due to limited access to hunting territories (Citation12). Other studies found that community isolation was associated with more frequent consumption of bush food, and in larger quantities (Citation6, Citation12) (Citation14, Citation39) (Citation40). Because Wemindji and Eastmain have less access to restaurants and because store-bought foods are more expensive in these communities than in Mistissini (Citation41), this result was surprising. The focus group participants suggested that this result could be explained by the presence of various promotional programs organized by the Mistissini Band Council to promote traditional food consumption. In winter and summer, the community offers free traditional food meals to the entire community 4 times a week. Meals are served in a traditional camp setting, where elders teach others how to prepare traditional food and make traditional goods such as snowshoes, moccasins and so on. It would be interesting to measure the influence of such programs in future studies. Because this program inspires this community to consume more traditional foods, it could be exported to other communities as a concrete way to promote traditional food consumption at the community level. Again, this result underscores the significant community influence on traditional food consumption. In addition, upon closer examination of the data on traditional food consumption, we found significantly greater consumption of game in Mistissini (Table ). It is possible that the wildlife population fluctuated, making game more available in 2005 than in 2007. Alternatively, moose may have been more accessible in the southern region where Mistissini is located. Thus, greater access to a variety of traditional foods may increase consumption frequency. Both hypotheses underscore the potentially strong environmental influence on traditional food consumption, as testified by the frequent mention of interpersonal, community and environmental factors by the focus group participants.

In the logistic regression, although no relationship was found between traditional food consumption and education level in previous studies (Citation39, Citation42), our results agree with the findings of Hopping et al. that a person with no formal schooling is much more likely to consume traditional foods (Citation43). Apart from the focus group participants’ explanations (Table ), this could be due to their exposure to traditional aboriginal education, whereby knowledge and skills in gathering, preparing and cooking traditional foods are acquired, which has been shown to promote traditional food consumption (Citation12, Citation14) (Citation39).

Studies have found that older people consume more traditional foods than younger people (Citation12, Citation14) (Citation39). Some of the older Cree were raised in the bush, where they were exposed to traditional foods and learned traditional skills at an early age. Because Crees began to settle in residential communities about 35 years ago, with the signing of the James Bay Agreement, younger people have been less exposed to traditional foods and lifestyles.

Some studies also reported that men consumed more traditional foods than women did (Citation40). Future studies could control for (either sex or sex and hunting status), 2 factors that showed strong collinearity in our analysis.

In our study, physically active people were more likely to consume traditional foods 3 days or more per week, a relationship that few studies have demonstrated. However, because a cross-sectional design was used, we were unable to establish a temporal relationship between traditional food consumption and walking (Citation44), and therefore could not determine whether being physically active favours traditional food consumption or whether the desire to consume traditional foods is independently associated with physical activity. Whereas the adoption of a balanced, holistic lifestyle, including physical activity and healthy eating, may positively influence traditional food consumption, the practices of hunting, trapping, collecting and preparing traditional foods require plenty of walking.

Although other studies have similarly failed to find a relationship between BMI and traditional food consumption, a relationship between normal BMI and high consumption of traditional foods would be expected. The focus group participants suggested that people with a higher BMI might tend to eat traditional high-fat foods such as bear grease, eat bigger portions, or use high-fat cooking methods. This highlights the importance of food type and cooking methods over the frequency of traditional food consumption. Additionally, the frequency of traditional food consumption might be an insufficiently sensitive factor to reveal an association.

Limitations

This study includes certain limitations, mainly concerning some of the independent variables. First, we predicted that traditional food consumption would be associated with a feeling of better health and wellbeing, because traditional foods are an integral part of miyupimaatisiiun (wellbeing) (Citation24). However, no such association was found, probably due to differing meanings of health between the Crees and the researchers. In future studies, questions on the feelings of health and wellbeing should be culturally adapted, and the meanings should be more thoroughly explored. Second, although we expected to find a relationship between worries about pollution and traditional foods, we did not find one. For over 30 years now, public awareness campaigns have been in place to warn against contaminants found in fish and animal organs. This lack of association was perhaps due to the fact the traditional food categories include all types of wild animals. Future studies could explore this association using only wild animals affected by contaminants.

Similarly, because data were taken from a cross-sectional study, the associations found cannot be used to infer a causal relationship (Citation44). Errors may also have occurred during the collection of quantitative data. It is possible that the lengthy duration of the interviews resulted in a measurement error, leading to the attenuation of the odds ratio. However, the pertinent study questions were asked at the beginning of the interview. A limitation associated with the use of food-frequency questionnaires is that they depend on the accuracy of the participants’ recall and self-reports. Not only must participants recall their eating habits over a 12-month period, but they must also provide the usual amounts eaten and the usual frequencies of eating each food.

Unfortunately, the focus groups were organized in Mistissini only. It would have been useful to include the opinions of Eastmain and Wemindji residents as well. However, we took several steps in our methodology to ensure the validity of our focus group results. We pilot-tested the question grid and we listened to the participants and asked them to clarify areas of ambiguity. We also created an environment where they could share their thoughts freely. The qualitative data and their analysis refined and explained the statistical results by exploring the participants’ views in greater depth. The collection of both quantitative and qualitative data enabled combining the strengths of the 2 research methods (Citation25).

Conclusion

The aim of this study was to conduct an initial exploration of factors influencing traditional food consumption using an ecological model, and further investigation along this line is needed. Whereas the quantitative analyses focused largely on individual-level factors, the qualitative analysis revealed that many collective factors were predominant, in the participants’ view, which highlights the importance of acting on family, community and environmental factors to increase traditional food consumption. Nevertheless, further studies using an ecological model are needed to investigate these influences. We believe that our findings can be used to design traditional food promotion strategies to enable the Cree of northern Quebec and other nations to improve their overall wellness.

Conflict of interest and funding

The project was partly funded by the Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay, Quebec, Canada.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the participants from Mistissini, Eastmain and Wemindji communities who generously shared their views and experiences. We are also grateful to the Cree Board of Health for their invaluable collaboration and for providing funding for this research, as well as access to the Environment and Health Longitudinal Study. Thanks to Margaret McKyes for linguistic editing. Finally, thanks to the Cree Nation of Mistissini, Eastmain and Wemindji for their support.

References

- Health Canada. A statistical profile on the health of first nations in Canada. 2004; Ottawa: Government of Canada.

- Bou Khalil C, Johnson-Down L, Egeland GM. Emerging obesity and dietary habits among James Bay Cree youth. Public Health Nutr. 2012; 13: 1829–37.

- Kuhnlein HV, Receveur O, Soueida R, Berti PR. Unique patterns of dietary adequacy in three cultures of Canadian Arctic indigenous peoples. Public Health Nutr. 2008; 11: 349–60.

- Kuhnlein HV, Receveur O, Soueida R, Egeland GM. Arctic indigenous peoples experience the nutrition transition with changing dietary patterns and obesity. J Nutr. 2004; 134: 1447–53. [PubMed Abstract].

- Ballew C, Tzikowski AR, Hamrick K, Nobmann ED. The contribution of subsistence foods to the total diet of Alaska Natives in 13 rural communities. Ecol Food Nutr. 2006; 45: 1–26.

- Nakano T, Fediuk K, Kassi N, Kuhnlein HV. Food use of Dene/Metis and Yukon children. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2005; 64: 137–46. [PubMed Abstract].

- Willows ND. Determinants of healthy eating in Aboriginal peoples in Canada: the current state of knowledge and research gaps. Can J Public Health. 2005; 96: S32–6. [PubMed Abstract].

- Sallis JF, Glanz K. Physical activity and food environments: solution to the obesity epidemic. Milbank Q. 2009; 87: 123–54.

- Raine KD. Determinants of healthy eating in Canada: an overview and synthesis. Can J Public Health. 2005; 96: S8–14. [PubMed Abstract].

- Glanz K, Mullis RM. Environmental interventions to promote healthy eating: a review of models, programs and evidence. Health Educ Behav. 1988; 15: 395–415.

- Kuhnlein HV, Receveur O. Dietary change and traditional food systems of indigenous peoples. Annu Rev Nutr. 1996; 16: 417–42.

- Chan HM, Fediuk K, Hamilton S, Rostas L, Caughey A, Kuhnlein H, etal. Food security in Nunavut, Canada: barriers and recommendations. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2006; 65: 416–31.

- Redwood DG, Ferucci ED, Schumacher MC, Johnson JS, Lanier AP, Helzer LJ, etal. Traditional foods and physical activity patterns and associations with cultural factors in a diverse Alaska Native population. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2008; 67: 335–48.

- Receveur O, Boulay M, Kuhnlein HV. Decreasing traditional food use affects diet quality for adult Dene/Metis in 16 communities of the Canadian Northwest Territories. J Nutr. 1997; 127: 2179–86. [PubMed Abstract].

- Booth SL, Sallis JF, Ritenbaugh C, Hill JO, Birch LL, Frank LD, etal. Environmental and societal factors affect food choice and physical activity: rationale, influences, and leverage points. Nutr Rev. 2001; 59: 21–39. discussion S57–65.

- Story M, Kaphingst KM, Robinson-O'Brien R, Glanz K. Creating healthy food and eating environments: policy and environmental approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008; 29: 253–72.

- Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Healthy nutrition environments: concepts and measures. Am J Health Promot. 2005; 19: 330–3.

- French SA, Story M, Jeffery RW. Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001; 22: 309–35.

- Delormier T, Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Food and eating as social practice: understanding eating patterns as social phenomena and implications for public health. Sociol Health Illn. 2009; 31: 215–28.

- Sobal J, Kettel Khan L, Bisogni C. A conceptual model of the food and nutrition system. Soc Sci Med. 1998; 47: 853–63.

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: research perspectives. Dev Psychol. 1986; 22: 723–42.

- Willows ND, Hanley AJ, Delormier T. A socioecological framework to understand weight-related issues in Aboriginal children in Canada. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012; 37: 1–13.

- Richard L, Gauvin L, Raine K. Ecological models revisited: their uses and evolution in health promotion over two decades. Annu Rev Public Health. 2011; 32: 307–26.

- Adelson N. “Being alive well” health and the politics of Cree well-being. 2000; Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 139 p.

- Creswell JW, Clark VLP. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2007; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 274 p.

- Ivankova NV, Creswell JW, Stick SL. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: from theory to practice. Field Methods. 2006; 18: 3–20.

- Egeland GM, Dénommé D, Lejeune P, Pereg D. Concurrent validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) in an Iiyiyiu Aschii (Cree) community. Can J Public Health. 2008; 99: 307–10. [PubMed Abstract].

- Zhou YE, Kubow S, Dewailly E, Julien P, Egeland GM. Decreased activity of desaturase 5 in association with obesity and insulin resistance aggravates declining long-chain n-3 fatty acid status in Cree undergoing dietary transition. Br J Nutr. 2009; 102: 888–94.

- Bobet E. Summary report on the Nituuchischaayihtitaau Aschii multi-community environment-and-health study. 2013; Chisasibi: Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay.

- Kleinbaum DG, Klein M. Logistic regression: a self-learning text. 2002; 2nd ed, New York, NY: Springer.

- Bonnier-Viger Y, Dewailly É, Egeland GM, Nieboer E, Pereg D. Nituuchischaayihitaau Aschii: multi-community environment-and-health longitudinal study in Iiyiyiu Aschii: Mistissini. Technical report: summary of activities, results and recommendations. 2007; Chisasibi: Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay.

- Lambden J, Receveur O, Marshall J, Kuhnlein HV. Traditional and market food access in Arctic Canada is affected by economic factors. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2006; 65: 331–40.

- World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. 2000; Geneva: WHO.

- Lemieux M, Thibault G. Kino-Québec . Savoir et agir. L'activité physique. Le sport et les jeunes.

- Krueger RA , Casey MA . Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. 2009; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 4th ed.

- Seale C . Oasks T . The quality of qualitative research. Guiding ideals. 1999; Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 41.

- Mays N , Pope C . Assessing quality in qualitative research. Br Med J. 2000; 320: 50–2.

- Batal M. Sociocultural determinants of traditional food intake across indigenous communities in the Yukon and Denendeh. [doctoral thesis ès Science]. 2001; Montréal: McGill University.

- Wein EE, Sabry JH, Evers FT. Food consumption patterns and use of country foods by native Canadians near Wood Buffalo National Park, Canada. Arctic. 1991; 44: 196–205.

- Pars T, Osler M, Bjerregaard P. Contemporary use of traditional and imported food among Greenlandic Inuit. Arctic. 2001; 54: 22–31.

- Duquette M-P, Scatliff C, Desrosiers Choquette J. Access to a nutritious food basket in Eeyou istchee – project report. 2013; Montreal, QC: Montreal Diet Dispensary.

- Erber E, Beck L, Hopping BN, Sheehy T, De Roose E, Sharma S. Food patterns and socioeconomic indicators of food consumption amongst Inuvialuit in the Canadian Arctic. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010; 23: 59–65.

- Hopping BN, Erber E, Mead E, Sheehy T, Roache C, Sharma S. Socioeconomic indicators and frequency of traditional food, junk food, and fruit and vegetable consumption amongst Inuit adults in the Canadian Arctic. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010; 23: 51–8.

- Gordis L. Epidemiology. 2004; Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. 335 p. 3rd ed.