Abstract

Background

Prostate cancer (PCa), the most commonly diagnosed cancer among men in the United States and Europe, is an escalating resource allocation issue across healthcare systems in the Western world. The impact of skeletal-related events, associated with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), is considerable with many new therapies being sought to treat these events in a cost-effective manner.

Aims

The aim of this paper is to provide insight into the level of constraints associated with devising cost frameworks for economic analysis of CRPC in the Irish healthcare setting.

Methods

An informal questionnaire was devised to obtain estimates of utilisation to populate a decision tree model; existing parameters from the literature were also employed. Cost parameters included Irish reference costs, and a costs literature review was undertaken; a healthcare payer perspective was adopted. Pharmacy dosages used for modelling costs were calculated for an average 75 kg male.

Results

The estimated average cost of care associated with adverse events in CRPC was €23,264. Approximately 40% of the costs of CRPC are attributed to skeletal-related events; therefore, reducing the number of skeletal-related events could significantly reduce the cost of care. In attempting to generate accurate and reliable cost parameters, this study highlights the challenges of conducting economic analysis in the Irish healthcare setting.

Conclusion

This study presents leading treatments and associated costs for CRPC patients in the Republic of Ireland (RoI), which are expected to steadily increase with demographic shifts. Further research is warranted in this area due to the limitations encountered in the study.

Prostate cancer (PCa) is seen as an escalating resource allocation issue across healthcare systems in the Western world, mainly due to demographic shifts, increasing incidence and detection, which leads to higher costs (Citation1, Citation2). It is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among men in the United States and Europe; in the Republic of the Ireland (RoI), PCa accounts for 27.9% of all cancer-afflicted men (Citation2–(Citation4)). In 2008, it was estimated that there were 258,133 deaths due to PCa worldwide; PCa accounted for 12% of all cancer-related deaths in the RoI. (Citation5, Citation6). Across Europe, the RoI had the highest incidence of PCa (2006–2010) and the 11th highest mortality rate; incidence is expected to continue to increase attributed to changes in detection practices. (Citation2, Citation4–Citation7)).

Survival rates for PCa are dependent on the stage of diagnosis and the organ concerned; tumours limited to the prostate have a 5-year survival rate of 98%, whereas metastatic cancers have a 5-year survival rate of 32.6% (Citation8, Citation9). Castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), a late-stage cancer which occurs when there is prostate-specific antigen (PSA) progression, despite consecutive standard hormonal manipulation, is typically a disease of elderly men and is associated with the development of osteoblastic bone metastases (Citation9–(Citation11)). CRPC metastasis to the bone poses a significant societal burden of cost; bone metastases are associated with severe pain in bone, accompanied by increased bone fragility and can lead to spinal cord compression due to their occurrence in the lumbar spine region as well as the pelvis (Citation12, Citation13). It is estimated that 80%–92% of men diagnosed with CRPC will have evidence of bone metastasis (Citation14, Citation15). Major developments have taken place in the treatment of CRPC, which has metastasised to the bone, with biosphosphonates, radiotherapy, and other emerging therapies extending the lives of CRPC sufferers. These therapies attempt to reduce the number of skeletal-related events (SREs), a major component of the cost associated with advanced PCa, as well as to alleviate pain, thus increasing quality of life and survival time (Citation15, Citation16). The impact of SREs on patients and society is considerable and many new therapies are being sought to treat this adverse event in a cost-effective manner (Citation16–(Citation18)). Undertaking economic evaluations and cost-effectiveness analysis in the RoI has many constraints; lack of detailed disease-specific reference costs coupled with geographical differences in treatment strategies result in a high degree of uncertainty in determining parameters necessary for cost-effectiveness analysis. The aim of this paper is twofold: to estimate the costs associated with the development of SREs attributable to CRPC and to evidence the level of constraints associated with devising a cost framework for CRPC.

Materials and methods

Clinical parameters

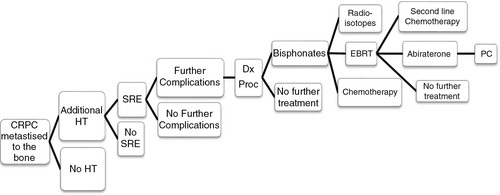

A patient algorithm for CRPC was devised from medical literature and previous economic studies in which expert opinions were reported (Citation18, Citation19). Twenty-two consultants across the main centres of excellence in the West, South and East of the RoI were invited to participate in the study, and the response rate was 18% (n=4). Although the response rate to our invitation to participate in the study was weak, we are confident that this sample of consultants reflect the treatment practice of CRPC in the RoI as two of the consultants treat PCa exclusively in their centres of excellence; given the limited resources and the time constraints of the study further attempts to strengthen the response rate were not possible. All respondents were male and worked in the realm of oncology for the Health Service Executive (HSE); three of the respondents worked in specialist cancer centres managed by the National Cancer Control Program (NCCP). Three of the six HSE regions were represented in the study by the respondents, including HSE West, South and South East, and Dublin/North East. An informal questionnaire was devised to obtain estimates of utilisation to populate a decision tree model; existing parameters from the literature were employed where consensus on treatment patterns could not be achieved. Questionnaires, employing both quantitative and qualitative approaches, ensuing from meetings with experts were, where possible, identical thus not only reducing bias but also providing a platform for discussion around obstacles in identifying consensus on parameters.

The study also sought consultation with a hospital pharmacist to ascertain expert opinion on additional costs associated with delivery of therapy options, adverse events to be included and wastage involved. Through this process, it was established that the weight for estimating dosages would be 75 kg, or 1.8 m2. The assumption was made that the patient cohort would have extensive metastases and, therefore, the mean length of survival was deemed 12 months in the model (Citation20). The probability of further treatment after the initial diagnosis of metastatic bone disease is also assumed in the model, as utilisation data were not available for this study.

Resource utilisation parameters

The study adopted the healthcare payer perspective. Pharmaceutical costs could not be disclosed due to contractual agreement between the hospitals and pharmaceutical companies. Costs of procedures were based on data from HSE Casemix (2012) and patient-level costing at St James's Hospital, Dublin (Citation21). Reference costs of pharmaceuticals were obtained from MIMS (Citation22) and hospital-only pharmaceutical costs (net price) were obtained from the British National Formulary (Citation23), and converted using the appropriate Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA) guidelines (Citation24). Where costs for a procedure were not available, literature costs were used Citation8, 12–24. Costs were reported in 2010–2011 Irish Euro. A number of assumptions were made due to lack of consensus and non-availability of data in the RoI. It was also assumed that additional hormone therapy (total androgen blockade) was prescribed for 2 months based on expert opinion (see ). For diagnostic procedures () all patients were assumed, in conjunction with expert opinion, to have two of each scan type; this included CT, MRI and X-ray costs.

Table 1. Diagnostic procedures: St James Hospital, patient level costing, 2011

The length of time the patient received bisphosphonates was estimated to be 3 months. The first-line treatment was chemotherapy comprising six doses. The second-line treatment probabilities were considered in consultation with expert opinion as utilisation data were unavailable (see ). Chemotherapy (second line) was estimated to be limited to three doses, whereas abiraterone acetate was administered for only a month. Additional costs included further complications such as bone pain, spinal cord compression, surgery of the bone and pathological fractures.

Table 2. Decision model transition probabilities

The cost of palliative care was calculated using information provided by the Irish Hospice Foundation on palliative care by location and was used in conjunction with the Irish Hospice Foundations ‘Audit of End of Life Care in Hospitals in the RoI’ (Citation28). Proportions of PCa patients with metastatic PCa were sourced from the literature and applied to 2011 incidence rates reported by the National Cancer Registry, Ireland (Citation29, Citation30).

Modelling methods

A decision model was constructed based on expert advice on the care pathway associated with CRPC using Treeage software. Available costs and outcomes were modelled to ascertain average costs associated with treatment and adverse events of CRPC. Transition probabilities for the decision model are detailed in and were sourced from the literature, where available, and expert opinion (Citation12, Citation14) (Citation25–Citation27)).

Results

The analysis estimates that the cost of treating CRPC (metastatic to the bone) in the RoI is €56,889 per patient based on the CRPC patient care pathway algorithm (). Included in this estimate are hospitalisations, medical interventions (such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy), imaging and drug costs; costs of further complications associated with the full treatment pathway were also included (). Approximately 40% of the costs are attributed to SREs (€23,264 per patient); therefore, reducing the number of SREs could significantly reduce the cost of care.

Fig. 1. Castration-resistant prostate cancer patient care pathway. HT, hormone therapy; SRE, skeletal-related events; Dx Proc, diagnostic procedures; EBRT, external beam radiation therapy; PC, palliative care.

Table 3. Costs associated with adverse events of CRPC

Total cost calculations highlight that palliative care accounts for 3% of the total costs, while fractures to the bone account for 16% of the costs. The highest proportion of costs were spent on treatment of bone metastases at 19%; this figure included the yearly cost of external beam radiotherapy, radioisotope treatment and the cost of chemotherapy. The cost of palliative care was estimated per location (); the most expensive care setting was the hospital, not surprisingly, followed by hospice and long-term care.

Table 4. Total costa of palliative care by location (all costs in €)

highlights the average cost of palliative care per patient. The average cost is €7,193 based on the following assumptions: 1) according to the Irish Hospice Foundation audit paper, between 20% and 30% of CRPC patients receive palliative care; 2) in 2011, there were 2,748 men diagnosed with PCa in the RoI; and 3) based on the literature, it was assumed that 7% of those diagnosed has bone metastases (Citation28–(Citation30)). Total yearly costs of care vary from €286,299 to €429,488 due to the variation in the estimates of those patients who receive palliative care ().

Table 5. Costs associated with treating patients in palliative care

Discussion

In attempting to generate accurate and reliable cost parameters, this study raises awareness of the challenges of conducting economic analysis in the Irish healthcare setting. Difficulties arose in the collection of utilisation data, as well as consensus on methods employed, given the level of variation in ‘best practice’ across centres of excellence. The records system in the RoI, the hospital in-patients enquiry (HIPE) scheme, does not currently facilitate linkages to patients’ records outside the in-patient setting (Citation31). To capture the treatment pathways accurately for purposes of populating economic models, a more encompassing system tracking all elements of patient care would improve efficiency and therefore provide more robust evidence leading to more informed policy for CRPC. A detailed utilisation database would also monitor and correct for regional disparities in the RoI in terms of resource use as reported in previous works (Citation32, Citation33).

The average cost of care associated with adverse events in CRPC was €23,264; the relative cost is higher than international comparisons mainly due to improvements in treatment options resulting in longer survival times (Citation8). This paper also raises concerns over the use of reference costs, as these costs are based on diagnosis-related group (DRG) costing, that is, an average package of care for a particular disease group; therefore, it does not allow for assessment of individual cases which lead to estimate bias (Citation33). There is limited insight as to how these reference costs are calculated and what components are included; therefore, it does not allow for transparency when conducting cost analyses for particular disease sub-groups.

Obtaining costs of hospital-only drugs also proved challenging, as each hospital acts as a separate entity in negotiating the price that they pay for drugs associated with the treatment of cancer; therefore, receiving different discounts as a result of variation in negotiation practices. Due to the variation in negotiation across hospitals, an average, representative cost of hospital-administered cancer drugs is difficult to estimate. As these high-cost therapies represent a significant burden of cost to the annual budget for health, it stands to reason that more stringent regulation on utilisation practises and price negotiations by a single government agency would reduce costs and variation in practise and, congruently, provide more transparency for future economic evaluations.

This analysis was subject to multiple limitations; the most obvious limitation is the use of published, bundled complication rates rather than actual rates of utilisation in the RoI. Given the lack of data available, the cost estimates obtained may not accurately reflect the cost of SREs in the RoI. The assumption of the weight of a patient with CRPC could be argued to be too low given the patient demographic and therefore estimated costs may be understated. The use of UK drug costs may not reflect the market in the RoI for pharmaceuticals as trade prices would not be comparable to costs in Irish hospitals; albeit a consensus across Irish hospitals on drug costs is also problematic. DRG average costs are based on a standard package of care; given the lack of national consensus on that package of care for CRPC patients, it is expected that using DRG-related costs for this study introduces a large degree of uncertainty in the estimates. Costs of specific intervention that could not be found in the literature were excluded from the study; these included the cost of ketoconazole and the radioisotope Samarium-153. At the time of this study, denosumab, arguably more potent than bisphosphonates, was not reimbursed in the RoI and so was not included. This study also did not include full drug costs, staff costs, and administration and wastage costs associated with CRPC due to non-availability of data. Finally, the scope of this project provided time and resources to investigate costs associated with the development of SREs in patients with CRPC alone and did not facilitate the cost of treating CRPC in general. However, future research in the area of cost associated with CRPC would allow a more in-depth assessment of the cost differential in treatment of those with and without SREs.

Conclusion

The estimated financial impact of cancer in the RoI is sizable; PCa in the RoI was recently estimated to amount to €51 million annually (Citation34, Citation35). Costs associated with adverse events of CRPC have not been examined to date within the Irish context. This study highlights the leading treatments and associated costs for CRPC patients in the RoI, which are expected to steadily increase. Further research is warranted in this area due to high variability in costs and lack of consensus on best practice, which may lead to inefficient and inequitable delivery of care.

Conflict of interest and funding

Siobhan Bourke was a health economics summer intern at Bayer Healthcare Ireland, and was funded to undertake the costing element of this analysis. The co-author's have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study; however, Caroline Gaynor was an employee of Bayer Healthcare Ireland at the time of commissioning this research.

Acknowledgements

The author's would like to thank Professor Ciaran O'Neill (NUI Galway) for his supervision and guidance, Professor Freddie Hamdy (University of Oxford) for his expertise and guidance, the two reviewers whose comments were very useful and the panel of experts who informed the patient pathway assumptions.

Notes

This article has been partly supported by an educational grant from Université Claude Bernard Lyon I, France.

References

- Roehrborn C , Black L . The economic burden of prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2011; 108: 806–13.

- Ferlay J , Parkin DM , Steliarova-Foucher E . Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer. 2010; 46: 765–81.

- Globocan. Fast stats. World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2008. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@epidemiologysurveilance/documents/document/acspc-027766.pdf [cited 12 February 2013]..

- Drummond FJ , Carsin A-E , Sharp L , Comber H . Trends in prostate specific antigen testing in Ireland: Lessons from a country without guidelines. Ir J Med Sci. 2010; 179: 47–49.

- Ferlay J , Shin HR , Bray F , Forman D , Mathers C , Parkin DM et al. . Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010; 127: 2893–917.

- O'Lorcain P , Comber H . Prostate cancer mortality predictions for Ireland up to 2015. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2007; 16: 328–33.

- Heidenreich A , Bellmunt J , Bolla M . EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part 1: Screening, diagnosis, and treatment of clinically localised disease. Eur Urol. 2011; 5: 61–71.

- Groot MT , Boeken Kruger CG , Pelger RC , Uyl-de Groot CA . Costs of prostate cancer, metastatic to the bone, in the Netherlands. Eur Urol. 2003; 43: 226–32.

- Dearnaley DP . Current issues in cancer: cancer of the prostate. BMJ. 1994; 340: 780.

- Scher HI , Morris MJ , Basch E , Heller G . End points and outcomes in castration-resistant prostate cancer: From clinical trials to clinical practice. J Clin Oncol. 2011; 29: 3695–704.

- Heidenreich A , Bastian PJ , Bellmunt J , Bolla M , Joniau S , Mason MD . Guidelines on prostate cancer. European Association of Urology, March 2013. http://www.uroweb.org/gls/pdf/09_Prostate_Cancer_LR.pdf [cited 1 April 2014]..

- Barlev A , Song X , Ivanov B , Setty V , Chung K . Payer costs for inpatient treatment for pathologic fracture, surgery to the bone and spinal cord compression among patient with multiple myeloma or bone metastasis. Am J Manag Care. 2010; 16: 693–702.

- Hagiwara M , Oglesby A , Chung K , Zilber S . The impact of bone metastases and skeletal related events on health care costs in prostate cancer patients receiving hormonal therapy. Community Oncol. 2011; 8: 508–15.

- Lage MJ , Barber BL , Harrison DJ , Jun S . The cost of treating skeletal-related events in patients with prostate cancer. Am J Manag Care. 2008; 14: 317–22.

- Mundy GR . Metastasis to the bone: Causes, consequences and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002; 2: 584–93.

- de Bono JS , Oudard S , Ozguroglu M , Hansen S , Machiels JP , Kocak I et al. . Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: A randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010; 376: 1147–54.

- Botteman MF , Meijboom M , Foley I , Stephens JM , Chen YM , Kaura S . Cost-effectiveness of zoledronic acid in the prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with bone metastases secondary to advanced renal cell carcinoma: Application to France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Eur J Health Econ. 2011; 12: 575–88.

- Djavan B , Nelson K , Kazzazi A , Bruhn A , Sadri H , Gomez-Pinillos A et al. . Immunotherapy in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Can J Urol. 2011; 18: 5865–74.

- Weinfurt KP , Li Y , Castel LD , Saad F , Timbie JW , Glendenning GA et al. . The significance of skeletal-related events for the health-related quality of life of patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Ann Oncol. 2005; 16: 579–84.

- Sabbatini P , Larson SM , Kremer A , Zhang ZF , Sun M , Yeung H et al. . Prognostic significance of extent of disease in bone in patients with androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1999; 17: 948–57.

- National Casemix Pogramme of the Health Services Executive. Ready reckoner of acute hospital inpatient and daycase activity & costs (Summarised by DRG) relating to 2010 costs & activities. National Casemix Programme. 2012. Available from: http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/Publications/ [cited 10 March 2013]..

- Mousseau M . Mims Ireland. 2012; Dublin: David Kelly.

- Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary. 2012; BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. Available from: http://www.BNF.org [cited 10 March 2013]..

- Ryan M . Guidelines for the economic evaluation of health technologies in Ireland. 2010; Dublin: HIQA. Available from: http://www.hiqa.ie..

- June–July 2012. Expert Opinion: Consultation with Professor Frank Sullivan, Director, Prostate Cancer Institute, NUI Galway; Dr. Eugene Moylan, Consultant Medical Oncologist, Cork University Hospital; Dr. John Kennedy, Consultant Medical Oncologist, St. James's Hospital, Dublin; Dr. Ray McDermott, Consultant Medical Oncologist, St Vincent's University Hospital, Dublin.

- Félix J , Andreozzi V , Soares M , Borrego P , Gervásio H , Moreira A et al. . Hospital resource utilization and treatment cost of skeletal-related events in patients with metastatic breast or prostate cancer: Estimation for the Portuguese National Health System. Value Health. 2011; 14: 499–505.

- Nalesnik JG , Mysliwiec AG , Canby-Hagino E . Anemia in men with advanced prostate cancer: Incidence, etiology, and treatment. Rev Urol. 2004; 6: 1–4.

- McKeown K , Haase T , Pratschke J , Twomey S , Donovan H , Engling F . Dying in hospital in Ireland: An assessment of the quality of care in the last week of life. Report 5, Final Synthesis Report. 2010; Dublin: Irish Hospice Foundation. Available from: http://epubs.rcsi.ie/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=icubhrep [cited 1 April 2014]..

- NCRI Cancer in Ireland 2011: Annual report of the national cancer registry. Ireland: National Cancer Registry. Available from: http://www.ncri.ie/pubs/pubfiles/AnnualReport2011.pdf .

- Nørgaard M , Jensen AØ , Jacobsen JB , Cetin K , Fryzek JP , Sørensen HT et al. . Skeletal related events, bone metastasis and survival of prostate cancer: A population based cohort study in Denmark (1999 to 2007). J Urol. 2010; 184: 162–67.

- Wiley M . Using HIPE data as a research and planning tool: Limitations and opportunities: A response. Irish J Med Sci. 2005; 174: 52–57.

- Burns R , Walsh B , Sharp L , O'Neill C . Prostate cancer screening practices in the Republic of Ireland – The determinants of uptake. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2012; 17(4): 206–211.

- Walsh B , Silles M , O'Neill C . The role of private medical insurance in socioeconomic inequalities in cancer screening uptake in the Republic of Ireland. Health Econ. 2012; 12: 1250–56.

- Sharp L , Timmons A . The financial impact of cancer diagnosis. 2010; Ireland: National Cancer Registry. Available from: http://www.ncri.ie/publications/research-reports/financial-impact-cancer-diagnosis [cited 14 April 2013]..

- Luengo-Fernandez R , Leal J , Gray A , Sullivan R . Economic burden of cancer across the European Union: A population-based cost analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013; 14: 1165–74.