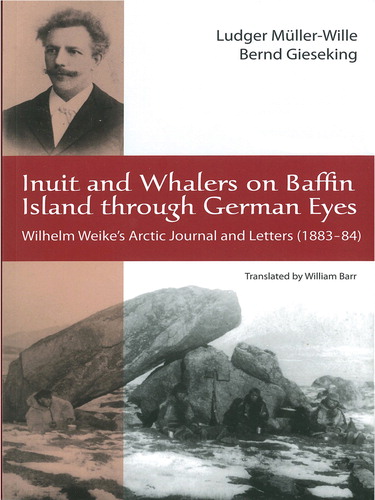

Review of Inuit and whalers on Baffin Island through German eyes. Wilhelm Weike's Arctic journal and letters (1883–84), by Ludger Müller-Wille & Bernd Gieseking, translated by William Barr (2011). Montreal: Baraka Books. 284 pp. ISBN 978-1-92682-411-6.

In 1883, Wilhelm Weike set off from Germany to spend a year on Baffin Island. He would probably have remained unknown if it had not been for the fact that he was the servant of the young and later well-known scientist, Franz Boas, on his expedition to Baffin Island in 1883–84. As part of his work, Boas made Weike keep a journal in order to supplement his own notes. Weike did this, although not always with great length or detail. The journal was published in German in 2008 to celebrate the International Polar Year and is now available to a larger audience in English.

The book Inuit and whalers on Baffin Island through German eyes is divided into two sections. The first contains the actual journal along with a few letters that Weike sent home to Germany while he and Boas were away. The second part provides the reader with a description of Weike's background, Boas's work and what happened to Weike after he returned from Baffin Island. Because the editors here draw on additional information and an extensive knowledge of the area and its history, it is in this part of the book that the reader gets the best understanding of the expedition itself. In addition, the second part fills the reader in on some of the things that went on during Boas's and Weike's stay that are not noted in the journal, such as Weike's relationship with an Inuit woman. It is also in Part 2 that the reader gains insight into the relationship between Inuit and whalers referred to in the title of the book. In this respect, the title of the book is slightly misleading. The journal entries seem, at times, to be more about making coffee for “Herr Dr.” than about life on Baffin Island. Wilhelm Weike does mention individual whalers and Inuit—and in a few cases, Inuit games and traditions—but readers who want to get a better understanding of the lives of Inuit and whalers and their relationship to one another will have to search elsewhere.

Weike's journal writing mostly focused on everyday chores, such as getting coffee ready for Boas, as it was his responsibility to take care of all the practical arrangements for Boas. As such, the journal is a valuable source for learning how the early expeditions to the Arctic region were conducted. Weike, for instance, noted the comings and goings of Inuit who informed Boas on various subjects. The journal also reveals the practicalities of everyday life, the extent to which Boas and Weike both adapted to Inuit ways of life and relied on the help of indigenous people. In Weike's journal, we have a narrative from a man belonging to the working class, a group that leaves little trace in the sources despite the fact that there were more working-class males among the non-Inuit inhabitants of Baffin Island than there were scientists and explorers. Weike was literate, but he was not trained in scientific observation and analytic thought. This is evident when one compares Weike's accounts with those of Boas (the latter inserted into the journal by the editors). At the same time, the journal provides unique insights into the relationship between Franz Boas and Wilhelm Weike, the extent to which they depended on each other, but especially how the class differences between master and servant were upheld—even under extreme conditions.

The layout of the book and the editorial work of Ludger Müller-Wille and Bernd Gieseking deserve to be highlighted: they evidently gave careful thought to the best way to render the journal comprehensible to the present-day reader. The editors have kept Wilhelm Weike's spelling of Inuit and English names of places and persons, but they also furnish the reader with an extensive list of footnotes with the names as they are written today. The footnotes reveal a thorough knowledge of the area and the people who lived there, and provide the reader with the background needed to appreciate Weike's journal without distorting it. Another example of careful editorial work concerns the few letters that Weike sent home, as well as comments written by Boas in his own journal and letters. These are inserted into the journal on the correct date, but in a different typography. This way the reader can compare several versions of the same occurrences: a dry account for the journal and a more cheerful description—stressing the exotic aspects of the Arctic world—for friends back home. The decision of the editors to merge the two accounts allows the reader to notice the way that they change in relation to the intended audience. At the same time, they reveal that stereotypical understandings of the Inuit and the Arctic—for instance, filthy Inuit women—were also reproduced in Weike's account. The perceived exoticism of the Arctic is evident in the photographs that illustrate the book. In one image, Boas and Weike pose in Inuit costumes.

Wilhelm Weike's journal is an interesting and unique account of an early Arctic expedition. In a genre filled with the writings of scientists and expedition leaders, Weike's working-class account provides a fresh voice and perspective. While not a treasure trove of information on whalers and Inuit, it nonetheless serves as a valuable source on polar expeditionary life in the 19th century.