Gladys Baker was born in Iowa City, Iowa, on 22 Jul 1908. She was the second daughter of Richard Phillip Baker and Katherine Riedelbauch. Gladys’ father was from England and had matriculated simultaneously at Oxford University and University of London, and he graduated from both in 1887. He had come to explore the United States in 1888 and settled in the exciting frontiers of Texas where he taught secondary school and music while reading for the bar. In 1900 he was living in a boardinghouse in Lamar, Missouri, where he was president and science master of Lamar College. Gladys’ mother, a daughter of German immigrants and a Lamar College music teacher, was living in the same boardinghouse. They became engaged and both left Lamar College for Anna Illinois Academy in 1901. Richard and Katherine were married 22 Feb 1902 in Glasford, Illinois. Richard developed a business making and marketing three-dimensional mathematical models for use in teaching. His models are in the collection of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, DC. In 1905 he accepted a mathematics teaching position at the University of Iowa, simultaneously pursuing a mathematics and physics doctorate at the University of Chicago. While at the University of Iowa, he taught mathematics, continued to build mathematical models and pursued his wide ranging interests. Kate cared for their two daughters, kept house, taught music and grew flowers.

Gladys and her sister Frances were raised in this sheltered, but intellectually exciting, environment. Gladys recalled that, “There were always music, books and interesting conversations with the family and visitors, all combining to make it a perfect environment in which to grow.” Frances received her doctorate at the University of Chicago and went on to teach mathematics at Mount Holyoke College and Vassar College where she served as chairwoman of the mathematics department. Gladys graduated from Iowa City High School with honors in 1926. After graduation she and Frances made a grand tour of Europe.

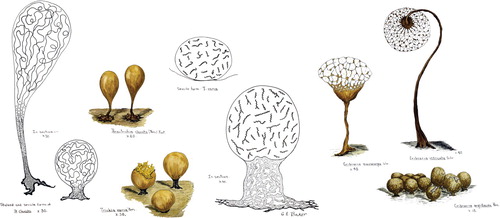

Gladys received a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Iowa in 1930 with majors in history and botany and a minor in zoology. She went on to pursue a master’s degree from the University of Iowa under the direction of G.W. Martin, mycologist. She completed her master’s in 1932 with a major in mycology and a minor in embryology. Her thesis work, a morphological study of myxomycete fructifications, was published by the University of Iowa Studies in Natural History in 1933. After graduation she was hired by the University of Iowa as a staff artist to T.H. MacBride. She drew the 21 plates of illustrations for MacBride’s and G.W. Martin’s 1934 classicPUBLICation, the worldwide monograph of “The Myxomycetes” published by Macmillan Co. of New York City.

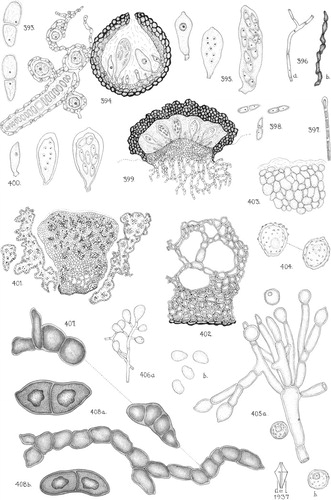

In 1933 Gladys went to Washington University in St Louis to earn her doctorate in mycology under Carroll W. Dodge. There she studied both general mycology and medical mycology on the Jessie R. Barr Fellowship. She received her degree in 1935 doing a monographic study of genus Helicogloea. Afterward she spent a year as a post doctoral research assistant in the Botany Department at Washington University, studying the lichens and their parasites collected during the highlyPUBLICized 2nd Byrd Antarctic expedition of 1933–1935. Lichens had been collected within 22 miles of the South Pole. The collections were shipped to C.W. Dodge at the Missouri Botanical Garden for identification. Dodge and Baker erected 84 new species of lichens, and Gladys illustrated the 25 plates. She also provided the plates for Moore and Andrews (1936), “Transitional Pitting in Tracheids of Psilotum.”

In Oct 1936 Gladys resigned her post doctorate position to follow her interest in teaching. From 1936 to 1940 she taught in the Biology Department at Hunter College in New York. While there she pursued her passion for music. She belonged to the New York Oratorio Society, which still performs choral music in the oratorio style and presents annual performances of Handel’s Messiah at Carnegie Hall. In 1940 she moved to Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. She started as an instructor in the Department of Plant Science and left in 1962 as chairwoman of the department. Her sister was chairwoman of the Mathematics Department at Vassar at the same time. Gladys was the first to teach a course in medical mycology at the seven sisters women’s colleges in the east. She directed three graduate students while at Vassar. Although her work at Vassar was dedicated to teaching, Gladys maintained an active research program, feeding her broad research interests in the summers.

As a new graduate student she had spent summer 1931 at the Friday Harbor Marine Lab of the University of Washington, studying phytoplankton and invertebrate zoology. She also spent summer 1946 as a research assistant to Neil B. Stevens, University of Illinois, working at the Marine Biological Station, Woods Hole, Massachusetts. She spent the summers of 1951 and 1952 at University of Montana Biological Station at Flathead Lake conducting research with her friend Louise Potter of Elmira College. She and Louise had National Science Foundation grants for their summer research periods, 1954–1956 and 1959–1962. In 1954–1955 Gladys spent a sabbatical doing research at the University of California at Berkeley in the lab of Ralph Emerson. She also received a grant from the Mycological Society of America (MSA) to help support her research in summer 1953. She was delighted with the MSA for establishing the G.W. Martin-G.E. Baker Fund, designed to aid young mycologists from small departments, who, because of heavy teaching schedules, might find it difficult to attract major grant support.

Gladys took research leave from Vassar College for the 1961–1962 academic year to work at the Department of Botany, University of Hawaii at Manoa. She stayed on at the University of Hawaii from 1963 until retirement as emeritus professor in 1973. Gladys had 10 master’s degree students and five doctoral students while at the University of Hawaii. Her students worked on projects reflecting the wide breadth of her background experiences in mycology. A major project during this period was the Island Ecosystems Integrated Research Program of the U. S. International Biological Program. Her research was on the soil fungi and phylloplane fungi from Hawaii Volcanoes National Park. Because of her interest in medical mycology she conducted a study with a clinical professor of pediatrics on molds in the homes and environments of asthmatic children. She also did research on the longevity of dermatophytes on the beaches and in the playground sandboxes of Oahu. While in Hawaii Gladys became deeply involved in the culture and natural history of the Pacific Basin. She enjoyed many activities with Beatrice Krauss, the University of Hawaiis expert on Hawaiian ethnobotany. She traveled extensively and collected wood carvings of animals from around the Pacific Basin. She was also actively involved with tropical botanic gardens throughout the basin. She and friends purchased a beautiful old “cottage” on Lake Geneva, New York, they called Hale Hui. Hale is Hawaiian for home, and Hui is Chinese for family association. Hale Hui became a center for social life during summers and holidays for her and her friends for many years. Hale Hui was noted for good humor, good cooking and good books. In post-retirement conversation with Martin Stoner at her Peoria, Arizona, home, Gladys said she never imagined that she would survive all of her Hale Hui friends.

Gladys needed to build a teaching collection of fungi for her mycology courses at the University of Hawaii. This presented a problem because the agriculture quarantine policies in Hawaii limited entry to only those fungi on the “approved” list, which was very short. Out of pique she asked Louise Potter and several mycologists and microbiologists from New York, Montana, central Pacific Islands and Japan to swab the bottoms of their shoes before deplaning in Honolulu. She cultured the fungi from these swabs. When the list of fungi of all kinds reached 65 she decided it was time to publish. Thinking the paper would be of little interest, she did not request reprints beyond the gratis 25. How wrong she was! Space exploration researchers overwhelmed her with reprint requests.

She was elected a member of Sigma Xi at Washington University in 1934. She had always kept her father’s Sigma Xi pin. In 1938 she was elected a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She was a charter member of the Medical Mycological Society of the Americas. She took great pride in the Martin-Baker Fund, both for having her name associated with her teacher and master’s thesis advisor and having the opportunity to help young mycologists start their own research.

In 1973 Gladys retired to Sun City, Arizona, where her home was filled with good books, music, southwestern Indian culture, treasured examples of Chinese art and her gardens. She continued to write, including an autobiography. Don Hemmes reported in Inoculum that “... she had written (on an old typewriter) a beautiful letter using such precise and flowery language as “frontispiece” and “top drawer”. Gladys’ students remember her as an effective and enthusiastic teacher, a scientist with the highest integrity, and a warm and caring friend. She was a gracious lady of many interests and talents, all executed with a style consistent with the English traditions of her father. It was a pleasure to have been associated with her.

GLADYS E. BAKERPUBLICATIONS

Fig. 1. Gladys E. Baker, 1908–2007, in 1943. Baker—teacher, mycologist, botanical illustrator, and representative of a more gracious time in our society—died at the age of 99 at her home in Peoria, Arizona, 7 Jul 2007, after a distinguished career and an active retirement among friends, books and music.

Fig. 2. Gladys Baker’s drawings of myxomycetes. Many of these drawing were used in both McBride and Martin (1934) and in CitationBaker (1933). Original plates are in the possession of the first author.

Fig. 3. Gladys Baker’s drawings of Antarctic lichens from CitationDodge and Baker (1938). The original plates are in the Farlow Reference Library of Cryptogamic Botany, Harvard Univ., Cambridge, Massachusetts. Used by permission.

References

- Baker GE. 1933. A comparative morphological study of the myxomycete fructification. Univ. Iowa Studies, Studies Nat History 14. 35 p.

- ———. 1936. Helicogloea graminicola (Bres.) Ann Rep Missouri Bot Garden. St Louis 23:89–91.

- ———. 1944. Heterokaryosis in Penicillium notatum. Bull Torrey Bot Club 71:367–373.

- ———. 1944. Nuclear behavior in relation to culture methods for Penicillium notatum Westling. Science 99:436.

- ———. 1945. Conidium formation in species of Aspergilli. Mycologia 37:582–600.

- ———. 1946. Addenda to the genera Helicogloea and Physalacria. Mycologia 38:630–638.

- ———. 1949. Freezing laboratory materials for plant science. Science 109:2838.

- ———. 1964. Fungi in Hawaii. Hawaiian Bot Soc Newslett 3: 23–28.

- ———. 1965. The inadvertent distribution of fungi. Can J Microbiol 12:109–112.

- ———. 1968. Antimycotic activity of fungi isolated from Hawaiian soils. Mycologia 60:559–570.

- ———. 1968. Fungi from the central Pacific region. Mycologia 60:196–201.

- ———. 1977. The prospect for mycology in the central Pacific. Lecture No. 8. Harold Lyon Arboretum, Univ. Hawaii at Honolulu. 51 p.

- ———, Dunn PH. 1971. Phylloplane mycota as a means of measuring co-evolution of fungi and endemic plants. Islands Ecosystems Integrated Research Program, US International Biological Programs. B-8.

- ———, ———, Sakai WA. 1974. The roles of fungi in Hawaiian Island ecosystems I. Fungal communities associated with leaf surfaces of three endemic vascular plants in Kilauea Forest Reserve and Hawaii Volcanoes National Park, Hawaii. Jul 1974. Islands Ecosystems, US International Biological Program. Technical Report 42.

- ———, ———, ———. 1979. Fungus communities associated with leaf surfaces of endemic vascular plants in Hawaii. Mycologia 71:272–292.

- ———, Goos RD. 1972. Endemism and evolution in the Hawaiian biota: Fungi. In: Kay EA, ed. A natural history of the Hawaiian Islands. Selected readings. Honolulu: Univ. Hawaii Press. p 409–431.

- ———, Kenner DD, Hohl HR. 1968. Preliminary observations on the fine structure of Micromonospora (Actinomycetales). Pac Sc 22:52–55.

- Blunt FL, Baker GE. 1977. The prospect for mycology in the central Pacific. Lecture No. 8. Harold L. Lyon Arboretum, Univ. Hawaii at Honolulu. 51 p.

- Chervin RE, Baker GE. 1968. The ultrastructure of phycobiont and mycobiont in two species of Usnea. Can J Bot 46:241–245.

- ———, ———, Hohl HR. 1968. The fine structure of two lichens: Usnea rockii and U. pruinosa. Can J Bot 46:241–245.

- Dodge CW, Baker GE. 1938. Botany of the 2nd Byrd Antarctic Expedition II. Lichens and lichen parasites. Ann Missouri Bot Garden 25:515–727.

- Dunn PH, Baker GE. 1983. Filamentous fungi of the psammon habitat at Enewetak Atoll, Marshall Islands. Mycologia 75:839–853.

- ———, ———. 1984. Filamentous fungal populations of Hawaiian beaches. Pac Sc 38:232–249.

- Kishimoto RA, Baker GE. 1969. Pathogenic and potentially pathogenic fungi isolated from beach sands and selected soils of Oahu, Hawaii. Mycologia 61:537–548.

- Lee BKH, Baker GE. 1972. An ecological study of the soil microfungi in a Hawaiian mangrove swamp. Pac Sc 26: 1–10.

- ———, ———. 1972. Environment and the distribution of microfungi in a Hawaiian mangrove swamp. Pac Sc 26: 11–19.

- ———, ———. 1973. Fungi associated with the roots of red mangrove, Rhizophora mangle. Mycologia 65:894–906.

- Oren J, Baker GE. 1970. Molds in Manoa: a study of prevalent fungi in Hawaiian homes. Ann Allergy 28: 472–481.

- Potter LF, Baker GE. 1952. Microbiology of Flathead and Rogers lakes. Bacteriolog Proc. G47.

- ———, ———. 1956. The microbiology of Flathead and Rogers lakes, Montana I. Preliminary survey of the microbial populations. Ecology 37:351–355.

- ———, ———. 1961. The microbiology of Flathead and Rogers lakes, Montana II. Vertical distribution of the microbial populations and chemical analysis of their environments. Ecology 42:338–348.

- ———, ———. 1961. The role of fish as conveyors of microorganisms in aquatic environments. Can J Microbiol 7:595–605.

- ———, Osterhoudt D, Baker GE. 1958. A collecting bottle for the microbiological sampling. Ecology 39:363–364.

- Stoner MF, Baker GE. 1981. Soil and leaf fungi. In: Mueller-Dombois D, Bridges K, Carson HL, eds. Island ecosystems: biological organization in selected Hawaiian communities. US/IBP Synthesis Series. Vol. 15. Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania: Hutchinson Ross Publ. Co. p 171–180.

- ———, Stoner DK, Baker GE. 1975. Ecology of fungi in wildland soils along the Mauna Loa transect. Islands ecosystems. US International Biological Program. Technical Report 75.

- Wang CJK, Baker GE. 1967. Zygosporium masonii and Z. echinosporum from Hawaii. Can J Bot 45:1945–1952.