Figures & data

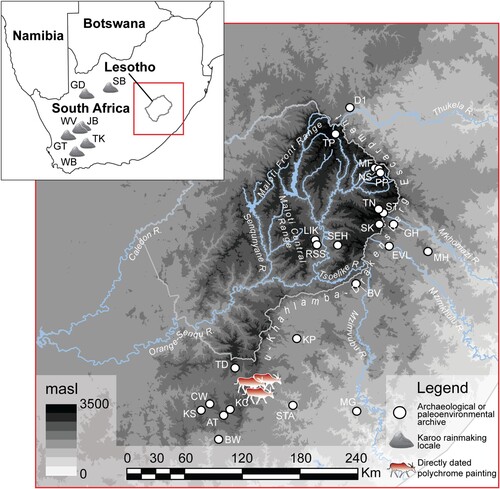

Figure 1. Map of southern Africa and Maloti-Drakensberg region with key sites/locales discussed in text or with Neoglacial-aged deposits. AT: Athol; BV: Belleview; BW: Bonawe; CW: Colwinton; D1: Diamond 1; EVL: eMvuleni; GD: Grootdrink; GH: Good Hope; GT: Groot Toren; JB: Jagersberg; KC: Kilchurn; KP: Kenegha Poort; KS: Kopshoring; LIK: Likoaeng; MF: MG: Mpongweni; Mafadi Summit; MH: Mahwaqa; PP: Popple Peak; NS: Njesuthi Summit; RSS: Rain Snake Shelter; SB: Strandberg; ST: Sani Top; SEH: Sehonghong; SK: Sekhokong; STA: Strathalan A; STB: Strathalan B; TK: Tierkloof; TN: Thabana Ntlenyana; TD: Tiffindell; TP: Tlaeeng Pass; WB: Wittberg; WV: Waterval.

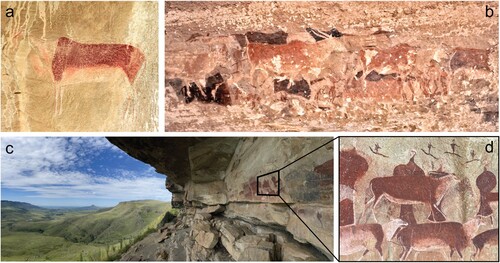

Figure 2. Examples of shaded polychrome eland paintings from various Maloti-Drakensberg locales, including: (a) Sehlabathebe, highland Lesotho; (b) Mount Fletcher, Eastern Cape, where a shaded polychrome eland is clearly superimposed on non-shaded bichromes; and (c & d) Game Pass Shelter, KwaZulu-Natal, so-named on account of its position overlooking a historic game trail into and out of the highlands. Images by the authors.

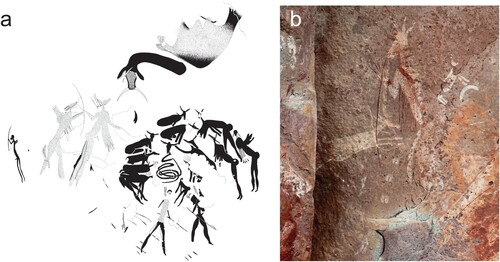

Figure 3. In (a) rhebok-headed tamers-of-the-game (left) approach a dangerous tusked rain serpent (top) painted to suggest that it emerges from behind the rock face, while other transforming rhebok-headed dancers interact with a smaller “tamed” snake – knowable by its rhebok head. In (b) a tamer-of-the-game with human body and rhebok head, surrounded by eland, bleeds from the nose and carries a hunter’s bow, while a rhebok emerges from a shadowy step in the rock face. Note the white spoor/hoof prints. Images by Challis.

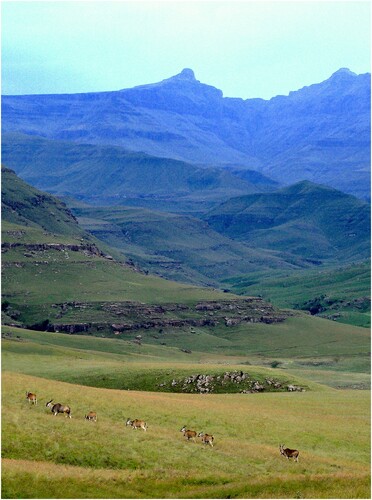

Figure 4. Eland antelope move through a southern Drakensberg valley towards the high passes into the spiritual hinterland of the high Maloti, where the San deity, |Kaggen, lives. They concentrated in large numbers, drawing hunter-gatherers to these altitudinous locales in a spring-summer aggregation phase that required heightened social and spiritual negotiation. Image by Challis.

Figure 5. In Lesotho’s Sehlabathebe National Park is a 1m long painting of a ritual specialist heralding the potential dangers of a superabundance of resources that concentrate seasonally at altitude (Challis Citation2019). With bulging stomach (evoking associations of gluttony and poor resource distribution), tusks, and three legs with clawed toes (evoking leonine proportions of both power and gluttony), the figure in question may represent just such an instance of the strong ritual specialist struggling to control excess fat and potency while dealing with the entities above and below the water. Image courtesy of James Pugin.

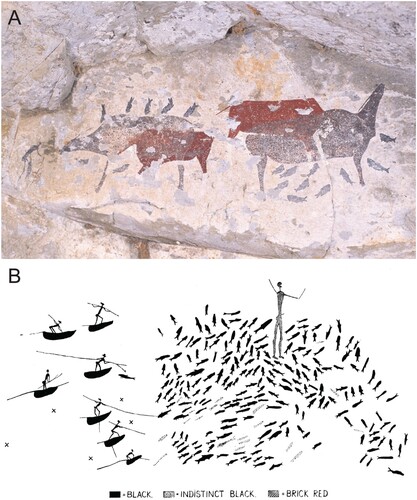

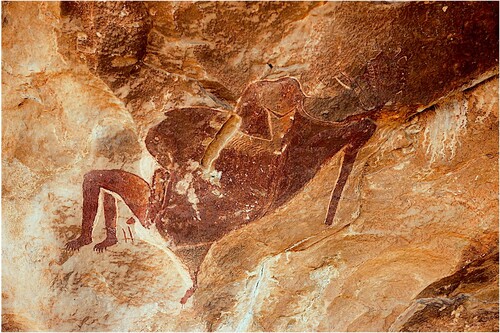

Figure 6. This large image – at Rain Snake Shelter on the banks of the Senqu close to Likoaeng – perhaps best displays !Khwa, the rain in the form of the giant serpent. Tamers-of-the-rain, some in dancing postures, are bending forwards and bleeding from the nose while others clap and hold out “charms” to placate the animal while it is led by a line to the nose. At its fattest point, the serpent’s body has six or seven “cut” marks, which parallel the incised cuts on the rock immediately below the painting (Challis et al., Citation2013). The cliff line in which the shelter is formed is also engraved with many cut marks, as if the place itself were the snake (Skinner and Challis, Citation2022; cf. Hollmann, Citation2007).

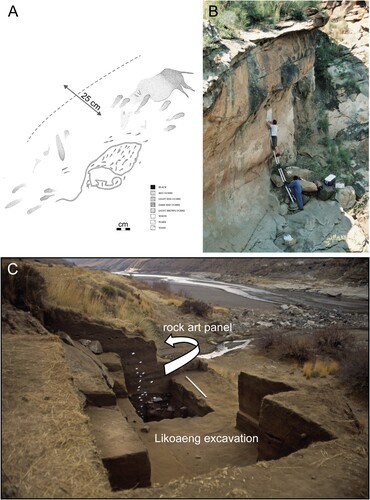

Figure 7. Rock art (a & b) and excavated archaeology (c) at Likoaeng, where millions of fish remains were recovered from Neoglacial-aged deposits. In a ravine immediately around the corner from the deposits, a rock art panel shows a dying eland and dancer ∼25 cm away from a probable fishing net and rain’s animal. The paintings are interpreted as depicting the harnessing of eland potency while in trance to summon the rain and thereby induce the seasonal running of migratory fish. Images courtesy of Peter Mitchell.

Figure 8. Selected palaeoenvironmental proxies (Parker et al., Citation2011) and faunal indices (Stewart and Mitchell, Citation2018a) from the archaeological sequence at Likoaeng, highland Lesotho, discussed in the text: (a) percentages of phytolith short cell morphotypes diagnostic of different grass types (Pooid C3, Panicoid C4 and Chloridoid C4); (b) percentages of bulliform phytolith morphotypes, argued to be preferentially laid down under conditions of enhanced humidity (Sangster and Parry, Citation1969; Andrejko and Cohen, Citation1984); (c) Likoaeng phytolith aridity index (Iph% = Chloridoid / Chloridoid + Panicoid), which provides a measure of xeric versus mesic grassland composition (Diester-Haas et al., Citation1973); (d) Likoaeng phytolith dicotyledon/Poaceae (D/P) ratio, a measure of woody (ligneous dicotyledon morphotypes) to grassy (Poaceae morphotypes) vegetation abundance and thus community openness (1 to 0, with 1 representing maximum woodland coverage and 0 none; Alexandre et al. Citation1997); (e) Likoaeng δ13C of sediment organic matter (δ13CSOM); (f) Likoaeng percentage proportions of C3 (versus C4) from δ13CSOM values (% of C3 plants = (δ13C −2 + 12.5)/−0.14; Wedin et al., Citation1995; after Bousman, Citation1991); (g) Likoaeng fish/mammal index (Σ NISP all fish / Σ [NISP all fish + NISP all mammals; 1 to 0, with 1 representing only fish and 0 only mammals]; Stewart and Mitchell, Citation2018a); (h) Likoaeng large ungulate/mammal index (Σ NISP all large ungulates / Σ [NISP all large ungulates + NISP all other mammals]; 1 to 0, with 1 representing only large ungulates and 0 only other mammals). The age/depth model employed is that found in Parker et al., Citation2011. The chronological boundaries of the late Holocene Neoglacial sensu lato can be seen in shaded blue, with the environmental and zooarchaeological inflection point that we identify at ∼2.6 ka highlighted.

![Figure 8. Selected palaeoenvironmental proxies (Parker et al., Citation2011) and faunal indices (Stewart and Mitchell, Citation2018a) from the archaeological sequence at Likoaeng, highland Lesotho, discussed in the text: (a) percentages of phytolith short cell morphotypes diagnostic of different grass types (Pooid C3, Panicoid C4 and Chloridoid C4); (b) percentages of bulliform phytolith morphotypes, argued to be preferentially laid down under conditions of enhanced humidity (Sangster and Parry, Citation1969; Andrejko and Cohen, Citation1984); (c) Likoaeng phytolith aridity index (Iph% = Chloridoid / Chloridoid + Panicoid), which provides a measure of xeric versus mesic grassland composition (Diester-Haas et al., Citation1973); (d) Likoaeng phytolith dicotyledon/Poaceae (D/P) ratio, a measure of woody (ligneous dicotyledon morphotypes) to grassy (Poaceae morphotypes) vegetation abundance and thus community openness (1 to 0, with 1 representing maximum woodland coverage and 0 none; Alexandre et al. Citation1997); (e) Likoaeng δ13C of sediment organic matter (δ13CSOM); (f) Likoaeng percentage proportions of C3 (versus C4) from δ13CSOM values (% of C3 plants = (δ13C −2 + 12.5)/−0.14; Wedin et al., Citation1995; after Bousman, Citation1991); (g) Likoaeng fish/mammal index (Σ NISP all fish / Σ [NISP all fish + NISP all mammals; 1 to 0, with 1 representing only fish and 0 only mammals]; Stewart and Mitchell, Citation2018a); (h) Likoaeng large ungulate/mammal index (Σ NISP all large ungulates / Σ [NISP all large ungulates + NISP all other mammals]; 1 to 0, with 1 representing only large ungulates and 0 only other mammals). The age/depth model employed is that found in Parker et al., Citation2011. The chronological boundaries of the late Holocene Neoglacial sensu lato can be seen in shaded blue, with the environmental and zooarchaeological inflection point that we identify at ∼2.6 ka highlighted.](/cms/asset/35daa8ec-daab-4843-ab95-1b32f5a7ae87/ttrs_a_2244923_f0008_oc.jpg)

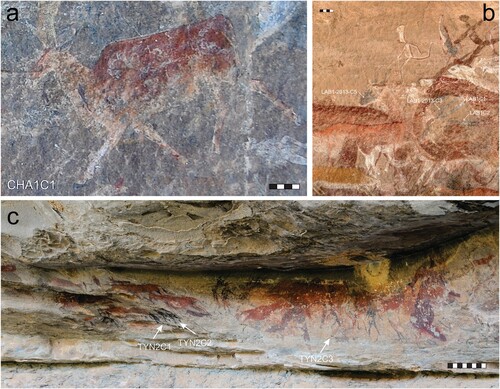

Figure 9. Sites in the Eastern Cape Drakensberg with directly dated shaded polychrome eland paintings. Carbon black was identified and isolated with pretreatment protocols to remove atmospheric carbon, and directly dated using AMS 14C, yielding results shown in . Images courtesy of Adelphine Bonneau and David Pearce.

Figure 10. Shaded polychrome fish at Likholong ha Piti on a tributary of the Senqu in southern Lesotho (see also Hobart and Smits, Citation2002; Hobart, Citation2003).Image and enhancement by authors.

Table 1. The four direct dates obtained for shaded polychrome eland in the Maloti-Drakensberg, after Bonneau et al. Citation2017a and supplementary material.

Figure 11. From the Eastern Cape Drakensberg, the upper painting (a) depicts an underwater encounter between a !Khwa-ka-!gi:xa tamer-of-the-rain and two dark !Khwa-ka-xoro rain’s animals surrounded by fish. The rain’s animals are superimposed on two bichrome eland, not by chance, because the eland is the quintessence of supernatural potency and itself came to symbolise the rain. In (b) we see Patricia Vinnicombe’s re-drawing of (part of) a “fishing scene” on the Tsoelike, not far from Sehlabathebe. A.J. Goodwin (Citation1949) noted the “fishing scenes” at Kenegha Poort and Mpongweni on the south-eastern side of the Drakensberg Escarpment and in 1960, Vinnicombe, already familiar with the Drakensberg “scenes”, began finding images of fishing in high Maloti (Vinnicombe, Citation1960). The human figure standing amongst the fish she thought must have been unrelated. Thanks to her own (1976), Lewis-Williams’s (Citation1981:112) and others’ later research, what we now know of San cosmology allows us to see the human figure underwater, controlling the movements of the subaquatic game. Images from ARADA, Rock Art Research Institute.